Abstract

The Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network (TBCCN) was formed as a partnership comprised of committed community based organizations (grassroots, service, health care organizations) and a National Cancer Institute designated cancer center working together to reduce cancer health disparities. Adhering to principles of community-based participatory research, TBCCN’s primary aims are to develop and sustain outreach, training, and research programs that aim to reach medically underserved, multicultural and multilingual populations within the Tampa Bay tri-county area.

Using a participatory evaluation approach, we recently evaluated the partnerships’ priorities for cancer education and outreach; perspectives on the partnerships’ adherence to CBPR principles; and suggestions for sustaining TBCCN and its efforts. The purpose of this paper is to describe implementation and outcomes of this participatory evaluation of a community/academic partnership, and to illustrate the application of evaluation findings for partnership capacity-building and sustainability. Our evaluation provides evidence for partners’ perceived benefits and realized expectations of the partnership and illustrates the value of ongoing and continued partnership assessment to directly inform program activities and build community capacity and sustainability.

Keywords: health disparities, community-academic partnerships, community networks program, community assessment, participatory evaluation

Introduction

The elimination of disparities in cancer incidence and mortality among medically underserved populations is a national priority (National Cancer Institute, 2010). As such, there is a growing interest in application of community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches to address and reduce cancer health disparities (Braun, Tsark, Santos, Aitaoto, & Chong, 2006; Lisovicz, Johnson, Higginbotham, Downey, Hardy, et al, 2006; Nguyen, McPhee, Bui-Tong, Luong, Ha-Iaconis, et al, 2006; Schoenberg, Howell, & Fields, 2012). At the core of CBPR, defined as an “orientation to research that aims at maximum feasible community participation in all phases of research”, is attention to collaborative community and academic partnerships that work to improve the health of the community (Buchanan, Miller, & Wallerstein, 2007).

In 2005, a National Cancer Institute (NCI) Comprehensive Cancer Center and 23 local community organizations (e.g., grassroots; nonprofit and faith-based organizations; community health centers/federally qualified health clinics/health departments; farmworker advocacy organizations; survivorship groups; adult education center) formed the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network (TBCCN). TBCCN was organized around a CBPR framework to address cancer health disparities within Florida’s Hillsborough, Pinellas, and Pasco counties (Gwede, Menard, Martinez-Tyson, Lee, Vadaparampil, et al, 2010; Meade, Menard, Luque, Martinez-Tyson, & Gwede, 2011). Rather than focus on a specific racial/ethnic group (e.g., only Hispanics or African Americans), community partners expressed an interest to focus on medically underserved populations given cross-cutting factors (e.g., limited access to cancer screening, low literacy, etc.). As such, community partner organizations within TBCCN serve diverse multicultural, multilingual populations including low-income, under-or uninsured, and a growing number of immigrant and foreign-born individuals. Examples of unique groups served by TBCCN include Hispanic migrant farmworkers and Haitian Creole speaking immigrants. Initially funded by the NCI’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, TBCCN was one of 25 nationwide community network programs dedicated to addressing cancer-related health disparities by increasing cancer screenings, providing quality and appropriate cancer education, and developing CBPR projects with the community (Gwede, Menard, Martinez-Tyson, Lee, Vadaparampil, et al, 2010; Meade, Menard, Luque, Martinez-Tyson, & Gwede, 2011). Building on this established and robust network of community partners, TBCCN has sustained its academic-community partnership through a second five-year cycle (2010–2015) as one of 23 NCI-funded Community Network Program Centers (CNPCs). CNPCs perform three key activities: research, training and outreach. Each of these aforementioned activities comprises a core with its own specific objectives. Additionally, an umbrella administrative core provides oversight on the activities of each core (see Figure 1 for TBCCN structure). Briefly, primary objectives for TBCCN include conducting evidence-based intervention research aimed at reducing health disparities (Research Core), training junior investigators in CBPR methodologies (Training Core), and working collaboratively to address and influence a reduction in cancer health disparities in breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, and cervical cancers via education and outreach (Outreach Core). Community and academic research partners communicate and share ideas for future TBCCN projects on a regular basis via partnership quarterly meetings, monthly administrative team meetings (involving community partners), a bimonthly newsletter, health events, workshops, and emails. The TBCCN partnership also holds an annual partners retreat to review the previous year’s achievements and plan for the upcoming year’s activities.

Figure 1.

TBCCN Organizational structure

Consistent with a CBPR approach, open dialogue within the community partnership is a prerequisite for the development of successful and sustainable interventions and programs (Minkler, 2004). Failure to engage the community can lead to the development of programs and interventions that are irrelevant or lack community benefit, thereby limiting implementation and influence (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). Thus, to enhance the success and sustainability of this partnership and collaborative network, we conducted a comprehensive needs assessment in 2007 that identified partner perspectives on issues such as the needs and priorities of the communities served and their cancer education and resource needs (Gwede, Menard, Martinez-Tyson, Lee, Vadaparampil et al, 2010). Key findings from this initial assessment revealed a need for increased access to cancer care (including prevention, screening, early detection, treatment, and survivorship) for medically underserved populations and an interest in more education and training for TBCCN’s partners to increase their capacity to reduce cancer disparities. As such, these findings informed and fueled TBCCN’s research and training efforts. Following the needs assessment, we completed a longitudinal social network analysis study (2007–2009) and identified that linkage types (e.g., shared information, shared resources, collaboration on community events) between TBCCN partners had increased over time, leading to greater network stability and trust (Luque, Martinez-Tyson, Bynum, Noel-Thomas, Wells, et al, 2011).

To ensure “continuous quality improvement” of TBCCN’s initiatives to reduce community cancer health disparities (Macaulay & Ryan, 2003; Williams & Yanoshik, 2001), a participatory evaluation was recently completed using CBPR principles. A participatory evaluation methodology was chosen over a more conventional process/outcome based program evaluation. This approach as defined seeks to create action-oriented initiatives that address partner needs, empower community partners to take ownership of the evaluation process, build capacity in the communities we serve, and generate means for enhancing the sustainability of the partnership (Scarinci, Johnson, Hardy, Marron, & Patridge, 2009; Whitmore, 1998). Therefore, each component of the evaluation process was developed, implemented and assessed by the collaborative effort of the community partner representatives, investigators and staff of TBCCN. We also sought to examine if current initiatives were addressing the needs of the community network partners and to determine the direction for future research and outreach initiatives. Consequently, the purpose of this paper is to 1) describe implementation and outcomes of a participatory evaluation process in a community/academic partnership and 2) illustrate the application of evaluation findings for partnership capacity-building and sustainability.

Methods

Design

The decision to utilize a CBPR approach to conduct a cross-sectional, mixed-methods community network participatory evaluation was born out of several network-wide discussions. The interview guide combined qualitative (semi-structured interviews) and quantitative (questionnaire, rating scales) data collection measures. Importantly, using mixed-methods to examine cancer-related priorities would allow for triangulation of the data and improve the range and richness of information gained during the assessment (Foss & Ellefsen, 2002).

Measure (Interview Guide) Development and Content

Consistent with a participatory approach (Macaulay & Ryan, 2003; Williams & Yanoshik, 2001), an interview guide was developed through a series of iterative steps with continuous feedback and input from a team composed of TBCCN researchers and community partners. We first developed a draft interview guide based closely on our prior needs assessment (Gwede, Menard, Martinez-Tyson, Lee, Vadaparampil, et al, 2010) and revised it through a recent review of the literature. Small in-person workgroups with equal participation of academic and community partners were convened to review sections of the interview guide to ensure that the questions were comprehensive. Next, the interview guide was pilot tested with a few organizations (n =4). Additionally, at a TBCCN partnership meeting, all partnering organizations had the opportunity to review the instrument and confirm that it was of acceptable length and content. As a final step, the interview guide was also pretested with TBCCN staff to ensure natural flow and question clarity.

The final interview guide was composed of four sections. In the first section we assessed the organizational characteristics of the partners including their mission, services provided, and demographic characteristics of the community members they served (e.g. ethnicity/race, gender, and age). In the second section we captured the partners’ perspectives on cancer-related education and training needs. Education/training needs were assessed by presenting a list of possible training topics to respondents for them to check off those of interest (e.g., CBPR research, how to find grant funding). An open-ended response item was also included for respondents to identify additional training topics of interest not listed. In addition, respondents were asked to rank their top training needs to allow us to prioritize future training/workshops. In the third section of the interview guide, we administered a 9-item measure assessing adherence to community-based participatory research principles using a 4-point response scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” Items were adapted from an existing network survey conducted by another community network program center (Weaving an Islander Network for Cancer Awareness Research and Training; WINCART) (Valente, Fujimoto, Palmer, & Tanjasiri, 2010). The adapted measure assessed areas such as whether TBCCN: builds on strengths and resources of the community; focuses on issues relevant to the tri-county area in addressing health disparities; and promotes activities that draw on the unique skills of community and academic partners. Higher scores endorsed on the scale reflect that an equitable balance of power is more evident in the community-academic partnership. In the final section, we assessed each organization’s perceived role in the TBBCN partnership, expectations (e.g., “What were your expectations of TBCCN when you first became a partner?”) and realized benefits of the partnership, and suggestions for network sustainability and partner capacity-building (e.g., In what ways do you think TBCCN can enhance efforts to improve community partner capacity/skills?).

Data Collection Procedures

To ensure all phases of the evaluation were congruent with CBPR approaches, akin to the development of the interview guide, a workgroup composed of community and academic partners developed a plan for data collection procedures. The partners identified the key informant approach as the best suited method for data collection. They also decided that a face-to-face interview method was most conducive to allowing the interviewer to probe or ask follow-up questions and to ensure that participants interpreted questions as intended. The community-academic team elected to host the interviews at the partner organization’s site, or at a centrally located site selected by the partner, to allow for uninterrupted time and access to partners in a comfortable and familiar setting.

Prior to participating in the interviews, the TBCCN representative from each partner organization (n = 23) received an introductory letter describing the interview procedures and goals of the participatory evaluation. Each partner organization was also given the option to include additional respondents with key knowledge or expertise at their discretion. Given the diversity in the types of organizations that comprise TBCCN, respondents varied in their roles at their respective partnering organizations ranging from executive leadership to social services coordinators. However, despite varied roles, respondents had great familiarity and involvement with the community and given their active roles within TBCCN also had familiarity with the partnership. The common thread across all respondents was their role in serving as the main liaison to the network.

Partnership representatives were informed that the interview was scheduled to last between 45 and 60 minutes and would be audio-recorded to ensure that the information was accurately captured. A TBCCN staff member scheduled interviews at times convenient for the representatives. Interviews were conducted by two TBCCN staff members with experience in mixed-methods research and community engagement. On the day of the interview, each respondent was given a copy of the informed consent document to review and sign prior to initiating the interview. Research staff administered the questionnaire, reading each question to participants and recording responses. Qualitative interview data was collected through audio recording, transcribed for analysis and supplemented by hand-written notes. This study received approval from the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies, means and standard deviations were computed to summarize the distribution, dispersion and central tendencies of responses for the quantitative data including the organizational characteristics, the CBPR adherence scale, and the rank order data regarding perceived cancer priorities. Qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis and the constant comparison method (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Patton, 2001). First, three researchers read through all transcripts and developed an initial codebook of a priori themes based on the interview guide content. The same researchers then independently hand-coded two transcripts with the initial code list, and additional codes were created and refined based on team discussions to resolve discrepancies until an inter-rater reliability of 90% was reached (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Patton, 2001). A summary of key findings was created and shared with the partners at a partnership meeting to verify that the findings accurately captured their perspectives. Although offered the opportunity to participate in the data analysis, none of the partners elected to do so.

Results

Characteristics of Community Partners’ Organizations

A total of 22 community partners (95.7%) completed the interview. The only partner who did not partake in the interview cited challenging organizational transitions and workload burden as reasons for nonparticipation. Partners were asked to describe the primary area of focus for their organizations. The most frequently cited areas of focus included health care services (n = 17), community outreach services (n = 21), health education and promotion (n = 21), and survivorship services (n = 11). Less frequently reported areas of service included job training or placement (n = 8) and technical training (n = 6). The majority of partner organization representatives reported that their organizations provided multiple services.

We also assessed the degree to which community partner organizations reported serving at-risk and vulnerable populations. Results indicated that 100% of the community partner representatives reported serving medically underserved populations, consistent with the focus of TBCCN. Although the majority of partnering organizations serve ethnically diverse clientele, a few partners reported serving clients who are predominantly Hispanic (> 90%) or Black (> 90%). For these organizations, the predominant ethnic/racial composition was based on the nature of their organizational mission, geographic location, and services offered. Diversity was also seen in the average age of clients served. The majority of partners reported that their organizations served populations of all ages (6 of our partners reported that they do not reach elderly populations and another 6 reported that they provide services exclusively for adults.)

Community Partner Cancer Education/Training Needs

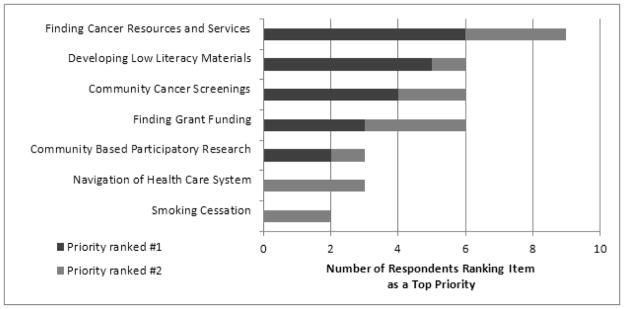

Partners identified multiple areas of interests for trainings and workshops to help increase the capacity of the partnership. Figure 2 depicts the highest rated priorities related to cancer education and training as defined by being rated a #1 or #2 top priority. For example, finding cancer resources and services in the community was rated as a top priority need. That is, 41% of partners reported it as the first or second highest priority need (i.e., 6 partner organizations ranked it as #1 and 3 partner organizations ranked it as #2). Other areas of interest for trainings and workshops included finding grant funding, community-based participatory research, navigation of the health care system and smoking cessation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Top Community Partner Cancer Education/Training Needs

Note. Figure 2 represents top training/education needs as defined by being ranked #1 or #2 by the community partners.

Partner perspectives on the partnerships’ adherence to CBPR

Overall, the respondents rated the partnerships’ adherence to CBPR was very high. For example, 100% of respondents reported that they strongly agreed (n = 21) or agreed (n = 1) that they felt acknowledged by TBCCN as partners with a sense of connection, shared values, and commitment to meeting mutual needs. In addition, 100% endorsed that they strongly agreed (n = 15) or agreed (n = 7) that TBCCN promotes collaborative, equitable partnerships. The mean scores on the individual adherence items (scored on a 4-point scale) ranged from 3.50 (SD = .6) to 3.95 (SD = .21).

Describing TBCCN and organizational role within TBCCN

When asked how they would describe TBCCN, the majority (n =18) of community partners used the words “collaboration” or “partnership” and believed that they shared mutual benefits by joining this network. Many (n =13) associated the partnership with enhancing access to cancer services and addressing cancer disparities. Other partners envisioned TBCCN as an organization that facilitates the exchange of ideas related to empowering the community in order to achieve health equity among underserved populations. When describing how their organizations functioned within the partnership, most partners described specific activities such as attending meetings (n = 11), collaborating on projects and educational events (n = 7), receiving or offering services (n = 5), and sharing information about organizational activities and programs (n = 3). One partner stated,

“I have felt that this partnership has been beneficial to both sides. We are out here in a rural community. We are connected to the community and TBCCN has great resources. To bring both of those together, we are a bridge to each other.”

Community Partners’ expectations of TBCCN and benefits

Community partners’ expectations for TBCCN included offering clinical cancer screenings, providing resources and funding for cancer prevention and control activities, serving as a networking platform, and providing cancer outreach and information resources. Similar to the outcomes of the 2007 TBCCN community needs assessment (Gwede, Menard, Martinez-Tyson, Lee, Vadaparampil, et al, 2010), most community partners (n = 19) agreed that the organization met or exceeded their expectations. One partner stated,

“Yes, I expected to learn all about cancer and how to eliminate disparities. But it has gone beyond that. It broadened my scope. It’s the whole package. We’ve brought in speakers who have got us thinking differently. Doing fun things with the community that’s educating them at the same time…. It makes it more accessible to people. When I started I had no idea where it would go. I never thought that we would be doing research at our facilities.”

Partners’ perceived benefit of the partnership included learning about the ongoing and planned events of other organizations and “feeling connected in the battle [against cancer].” With regards to the role of TBCCN, one partner stated,

“I think we -I say ‘we’ because I feel a part of TBCCN- are a health community network. We bring together community organizations, entities, or partners to learn, share, and take part in what the community needs.”

A commonly reported benefit of being a TBCCN partner was the opportunity to collaborate with the community and other partners (n =11). Furthermore, it was noted that benefits also included an increase in awareness about disparities, participatory research, specific cancer center services and resources, as well as financial resources. Respondents also noted that the partnership enhanced resource-sharing between medical and community-based organizations. For example, one partner described how his organization identified two men in need of prostate cancer screening and another TBCCN partner was able to offer screenings at no charge.

Community Partners’ ideas for capacity-building and enhancing sustainability

The current evaluation was instrumental in identifying several capacity-building needs as well as suggestions to support sustainability of the partnership. Community partners identified multiple approaches to sustain TBCCN efforts through increasing community involvement in each core (Table 1). At the administrative core level, respondents (n = 8) suggested increasing community partner involvement in TBCCN’s leadership and direction of activities by fostering leadership within individual members and involving members in new and emerging projects. Partners expressed that a community co-led TBCCN partnership would be better poised for sustainability, if NCI funding should cease. One partner noted, “We need to train the partners as leaders.” Another partner stated, “I think that the more integration into the programs with the partners that TBCCN has, the more the partnership will be sustained.” Prompted by the partners’ interest in increased leadership opportunities, the role of the community liaisons (i.e., the community partners who serve on the Outreach and Trainings cores and provide input and direction on core activities) has evolved and matured with specific leadership opportunities such as co-chairing TBCCN events, setting partnership meeting agendas, and co-facilitating partnership meetings. Another important suggestion to enhance sustainability was the need to increase visibility of TBCCN throughout the community. Many partners (n = 12) mentioned the desire to promote the network as a good resource that makes a difference in the community through local media coverage. During a dissemination workshop held during summer of 2014, the community liaisons worked with TBCCN investigators to co-author publications for academic journals and lay publication outlets. In addition, the partnership recently developed a “dissemination video” that highlights the partnership and the outcomes of the community-academic partnership. This video, which can be used as a media tool within each partner organization, was in response to the partner’s identified need to further increase TBCCN visibility in the community

Table 1.

Partners Identified Areas for Capacity Building

| Capacity building priority areas | TBCCN Core | Implementation Response | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed Activities | Planned Activities and Next Steps | ||

| Increasing opportunities for leadership | Administration | Community liaisons co-lead the Outreach and Training Cores and are part of the Administrative Core team. They provide input and direction for the health promotion and outreach, and training activities of TBCCN. The role of the liaisons has evolved for greater leadership opportunities (e.g., help to co-facilitate meetings, set meeting agendas, co-chair TBCCN events). | Liaisons were an integral part of a dissemination workshop held summer 2014 assisting in the development of co-authored publications for academic journals and local media outlets regarding research findings and programmatic outcomes |

| Grant writing skill-building | Training | Conducted a grant writing workshop with community partners to help identify appropriate funding mechanisms and teach community grant-writing best practices | Continue sharing grant-related resources and funding mechanisms through various channels (quarterly meetings, social media, email blasts) |

| Enhancing community engagement and visibility of TBCCN | Training | Conducted a policy and advocacy workshop with community partners to gain a better understanding of policy and advocacy and illustrate how to use these tools for community capacity building | Collaborate at a future partners’ meeting to identify ways for TBCCN to participate in cancer-related policy efforts We are in the final stages of creating a dissemination video to help community groups better understand the mission of TBCCN, and to introduce TBCCN to new community and legislative entities. |

| Resource sharing throughout the network | Outreach | Creation of a work group to create a colorectal cancer resource guide for Hillsborough county with a focus on cancer education, screening and survivorship support Resource sharing amongst partners at quarterly meetings and through social media outlets, email blasts and newsletters |

A workshop focusing on navigation of the healthcare system was recently implemented. The workshop included a segment on the identification of such resources. Future workshops on this topic are planned. |

| Increasing capacity through health education | Outreach | A detailed educational session pertaining to lung cancer rates, early detection, screening and treatment options was conducted at a partners’ meeting and facilitated by an academic researcher with expertise in behavioral intervention for smoking cessation | Future educational sessions are scheduled to take place at future partners’ meetings with the addition of a health education segment to the quarterly partners’ meeting agenda. |

| Leveraging funding for network sustainability | Research | CHE supplement (from NCI) – administrative supplement to TBCCN parent grant to empower farm-working women to follow cervical cancer screening recommendations utilizing a health coaching model Leveraged new funding (State of Florida) for creation of a colorectal cancer screening educational DVD and photonovella in Spanish Trainee pilot funding from TBCCN parent grant – small pilot awards for junior investigators to engage in CBPR-oriented research with TBCCN community partners. Current topics include: health literacy for cancer education, bridging the digital divide through an understanding of health communication preferences, second hand smoking in public housing, health coaching for breast cancer survivors |

Projects are in process. Once data is analyzed, findings will be disseminated to the partnership. Findings from projects are expected to fuel larger scale grant applications involving CBPR and using TBCCN infrastructure. |

A key suggestion for building network capacity was related to increasing training efforts; specifically to strengthen grant writing skills and enhance community engagement. From the partners’ perspectives, funding was cited as the greatest factor related to the sustainability of TBCCN.

Through community engagement our partners expressed a desire for TBCCN to “become a household name.” By engaging local politicians and local leaders, a few partners believe that this “community buy-in” was integral to sustain the efforts of TBCCN.

As illustrated in Table 1, multiple completed and planned partnership activities were directly informed by the current participatory evaluation and identified capacity-building needs. For example, we recently held workshops with a focus on community grant-writing and policy and advocacy as tools for community capacity building. Both workshops were led by representatives from TBCCN partnering organizations that have had continued success with obtaining external funding, lobbying and grassroots community organizing. As a result of the policy and advocacy workshop, plans are currently underway to identify ways for TBCCN to participate in cancer-related policy efforts.

In the Outreach core, many partners (n =13) identified the provisions of resources as fundamental to the longevity of the network as it relates to efforts to improve partners’ ability to provide care and resources. Partners felt that it was imperative to share health education resources with each other and to create a system that would help the communities served by TBCCN access cancer education, screening and survivorship support services efficiently. Partners also identified staying current with cancer health education an important facet of the group. Fueled by these findings, a workgroup was recently created with TBCCN partners to collaborate on the creation of a tri-county cancer community resource guide to identify local cancer prevention, screenings, treatment, and survivorship resources. A significant inherent challenge, identified at a recent meeting of TBCCN partners, was the need to provide accurate and current information in a fluid landscape with constantly changing resources. In addition, given the time and resources needed to gather this information for all cancer sites, the partnership decided that a more feasible approach would be to begin with one cancer site, colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer was selected because access to screening and diagnostic resources for this cancer type (e.g., colonoscopies) is difficult for uninsured or underinsured persons. The development of this resource guide is an important goal of our partnership in the upcoming months.

Finally, for the Research core, partners stated that the network should seek funding by writing grants as a collective. Several partners (n = 8) expressed interest in leveraging the current grant to seek additional funding opportunities for network sustainability independent of the life of the parent grant. TBCCN has been successful in obtaining several additional funding opportunities to further the work initiated in our partnership. For example, our newly awarded community health education supplement builds on a prior TBCCN project, in which a set of Spanish-language educational cervical cancer cards were developed and evaluated with Hispanic farmworker women in a clinic setting. Drawing on this work, and in collaboration with another TBCCN community partner that serves Hispanic farmworkers, ambassadors (women from that community) were trained to deliver cervical cancer education using a health coaching model. Additionally, we recently received funding from the State of Florida for creation of a colorectal cancer screening education DVD and photonovella for Latinos using a community-engaged methodology. Finally, TBCCN extended pilot awards to five junior investigators for CBPR-oriented research projects. Pilot study topics include: Developing a health coaching model for breast cancer survivors, Improving health literacy skills, Bridging the digital divide through an understanding of health communication preferences, Assessing perspectives related to household smoking bans among low-income African-Americans. These projects represent collaboration with multiple community partner organizations and align with the evaluation results as key approaches to sustain the efforts of TBCCN.

Discussion and Lessons Learned

The current participatory evaluation sheds light on many benefits and accomplishments of the partnership and informs future directions. An important goal of the evaluation was to measure community partners’ perspectives of TBCCN with regard to cancer-related education and training needs, adherence to CBPR principles, expectations and benefits of membership, and ideas for capacity building and sustainability. Overall, findings suggest favorable impressions and meaningful benefits of the TBCCN partnership. As mentioned previously, the results of this evaluation were presented at a TBCCN partners meeting, which continued the dialogue on ways to address partnership priorities and concerns. Two researchers presented key findings via PowerPoint and each meeting attendee received a printed executive summary detailing these results. After the formal presentation, the partnership engaged in discussion and verbally conveyed that their perspectives were accurately represented.

A key success of TBCCN is the constant and enriching dialogue between researchers and community partners resulting in high quality and beneficial outreach, training and research deliverables. This is achieved through the joint community and academic planning and delivery of interactive and engaging network activities. Such activities serve to educate, inform and shape the direction of the cores and the overall network. For example, involvement and engagement of community partners as facilitators of the journal and book clubs, advocates for our youth program (Youth Ambassadors Reaching Out), and advisors for our research projects help to enrich the core activities of the network. In short, outreach and research projects have greater relevance for the community due to this partner involvement and engagement. Also, community partners frequently express satisfaction with community-capacity and learning activities, (such as grant writing and policy workshops), that allows for the mutual exchange of ideas and lessons learned. Last, a central success is conduct of research that benefits communities and addresses attendant access concerns voiced by community partners. Specifically, access to colorectal cancer screening has been addressed through an ongoing large scale research project. As such, this mutually beneficial research project offers direct benefit to community members while advancing academic research efforts. An aim of this paper was to illustrate the application of evaluation findings for partnership capacity building and sustainability. As depicted in Table 1, this evaluation has been fruitful in translating findings into current and planned partnership activities. As the current TBCCN five year funding period comes to a close in the fall of 2015, sustainability is an ever-present issue for the partnership. As described by Israel and colleagues (2008), sustainability is multidimensional and includes: sustaining relationships and commitments among the partners involved; sustaining the knowledge, capacity and values generated from the partnership; and sustaining funding, staff, programs, policy changes and the partnership itself. Sustainability of relationships and commitments among our partners is evidenced by the high scores on the adherence to CBPR principle scale, demonstrating an equitable balance of power among partners. Furthermore, the most commonly reported benefit of TBCCN was the opportunity for collaboration. In evaluating sustainability of the knowledge, capacity and values generated from the partnership, we can look to the unique expertise of each community partner representative. Members of the TBCCN partnership are interested and involved in each aspect of the research project from design to dissemination. The ability to constantly reframe research questions in the context of community benefit will help to ensure sustainability. The sustainability of funding and center infrastructure can be measured by leveraging the TBCCN parent funding for administrative supplements; however, finding one funding source to support the entire CNPC is a challenge. As such, TBCCN is leveraging the success of the parent grant to diversify funding sources, such as the State of Florida Bankhead Coley Cancer Research Program. Future directions for network evaluation will include a more in-depth measurement of sustainability, including partner interest and ability to continue core TBCCN programs in the absence of the primary NCI funding. In addition, future evaluation efforts will be expanded to assess the influence of TBCCN on community perceptions of the Cancer Center.

Lessons Learned

The most valuable lesson learned from this participatory evaluation is that ongoing community partner guidance and involvement is vital to the success, growth and sustainability of a community-academic partnership. It is through the findings of our participatory evaluation that we were able to understand the needs of the network and respond quickly with relevant and desired capacity-building activities. As such, we continue to explore and plan novel activities that encourage mutual learning and participation of community-academic partners. Building on this overarching tenet of community-based participatory research, we present the following lessons learned and recommendations:

Integrating community representatives as liaisons for each core bolsters the network’s success as it allows greater integration of community perspective in the leadership and direction of the network. Although TBCCN has always had community representatives informing center activities, this role has evolved and matured with specific leadership directed activities (e.g., co-chairing TBCCN events).

Recognizing that each partnering organization brings unique expertise to the network in a way that instills authenticity and effectiveness to cancer education and outreach programming in the Tampa Bay community.

Sustainability of the network is powered by leveraging the partnership to expand resources, funding and capacity-building efforts.

Community feedback is valuable and greatly contributes to sustainability of a community academic partnership.

Limitations

We acknowledge that a limitation of our data collection procedures (i.e., face-to-face interviews) may be a tendency to respond in a socially desirable manner. This limitation is tempered by the fact that community partners selected in-person interviews as the mode of data collection because it allows for uninterrupted time and access in a comfortable setting. Another concern is the generalizability of our results because, in most circumstances, a single representative provided responses for the organization. Future assessments of the partnership may also consider supplementing in-person interviews with anonymous surveys with multiple community representatives to enhance the validity of this data.

Conclusion

Findings underscore the importance of conducting periodic program evaluations within community-academic partnerships to assess progress and future needs. Indeed, to effectively reduce cancer health disparities, ongoing assessments are needed to delineate the persistent and changing community priorities. Equally important is the need to measure our performance as a partnership. Admittedly, findings may reveal broad and specific challenges that as a regional partnership we are unable to tackle (e.g., access issues related to transportation and health insurance); however our shared mission enables us to consider novel strategies that have relevance to the local-regional community (e.g., creation of a resource guide).

As described above, the results of the current evaluation have had immediate implications in directing TBCCN’s efforts (e.g., conducting grant workshops, creation of workgroup to develop a resource guide). Also, we plan to conduct future evaluations that are more frequent and focused to regularly monitor whether the needs and priorities of the community are aligning with planned outreach and research activities. Due to the evolving needs of this cancer partnership, it is critical to continually gauge community partners’ preferences for future activities, projects and sustainability. In the spirit of CBPR, collaborating to identify and utilize this information will help the partnership conduct more relevant and effective cancer prevention and control education, research, and outreach aimed at reducing cancer health disparities.

Highlights.

Participatory evaluation enhances the benefits of community-based research

Capacity is increased by resource-sharing among clinic and community organizations

Increasing community involvement in leadership roles is vital for sustainability

Each partner brings a unique expertise to the network that instills authenticity

Sustainability is powered by leveraging the partnership to expand resources

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network partners for their participation in creating, implementing and disseminating the findings from our evaluation. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute U54 CA153509 and in part by the Biostatistics Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA76292). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Biographies

Vani Nath Simmons, PhD, is an Associate Member in the Division of Population Sciences, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute. She is co-director of the Outreach and Training cores of the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network. She has expertise in the development of smoking cessation interventions for special populations including ethnic minorities.

Lynne B. Klasko, MPH is the Program Manager for the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute. Lynne is interested in community-engaged research concerning cancer survivorship and screening behaviors, with the goal of reducing health disparities.

Khaliah Fleming, MPH, CHES, co-director of the Outreach Core of the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network Outreach Core housed at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center. Prior to her current role, Khaliah served as a community health outreach worker with the Center for Equal Health and as a Peace Corps volunteer. She received her MPH from the University of South Florida and her Bachelor’s degree from Spelman College. Currently, she serves as the president of the Florida Society for Public Health Education and as a board member for the Society for the Analysis of African American Public Health Issues.

Alexis M. Koskan, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Clinical at the University of Miami School of Nursing and Health Studies. Her research focuses on community-engaged studies aimed at HPV-related cancer prevention and control. She is also currently the Interim Coordinator of the Community Engagement, Dissemination, and Implementation Core (CEDI) of the UM School of Nursing and Health Studies’ National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities-funded Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro.

Nia Jackson an undergraduate student at the University of South Florida majoring in Sociology. Her research interests include health advocacy and health behavior. Under the mentorship of Dr. Cathy Meade in the Health Outcomes & Behavior department at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Nia is working on outreach and education programs to benefit community members from medically underserved neighborhoods. Her career goal is working with health policy and health disparities.

Shalewa Noel-Thomas, PhD, MPH is a Manager in the Department of Social Services, Hillsborough County and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the University of Florida. She leads the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of community-based social service programs focused on self sufficiency and self management. She leads workforce training and development programs. Her areas of expertise include community-based program development and implementation, workforce development, health disparities, and community-based participatory research.

John S. Luque, PhD, MPH is an Associate Professor in the Department of Community Behavior and Education, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health at Georgia Southern University and a Collaborator Member of Moffitt Cancer Center. He is currently the Principal Investigator of several research projects funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. His research interests are in cancer education and lay health advisor interventions, with a focus on Latino immigrant populations.

Susan T. Vadaparampil, PhD, MPH, is a Senior Member in the Division of Population Sciences, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute. She has developed a research program applying behavioral science, epidemiology, health services, and clinical perspectives to improve understanding, develop interventions to increase uptake, improve health outcomes, and reduce health disparities associated with genetic counseling and testing for hereditary cancer and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination.

Ji-Hyun Lee. DrPH is an Senior Member of Biostatistics at Moffitt Cancer Center. She is also Full Professor of Biostatistics & Oncologic Sciences at the University of South Florida. Ji-Hyun has collaborated extensively in cancer research with researchers from the Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, Cancer Epidemiology Program, and Experimental Therapeutics Program. She is a primary biostatistician for the breast and hematology research groups at the Cancer Center. Ji-Hyun is a Certified Professional Statistician through the American Statistical Association (PStat®).

Gwendolyn P. Quinn, PhD, is a Senior Member at Moffitt Cancer Center in the Health Outcomes and Behavior Program and a Senior Professor at the University Of South Florida College Of Medicine, College of Oncologic Sciences. She is Director of the Moffitt Survey Methods Core. She is a Health Psychologist whose research focuses on assessing the behavioral determinants of consumer decisions and choices about health. She is Director of the National Training Collaborative for Social Marketing that trains health care professionals in the field of social marketing.

Lounell Britt, MPA is the Executive Director of the James B. Sanderlin Family Cener, overseeing a multitude of programs that offer life skills, legal advice, computer classes, spouse-abuse intervention, music classes, health information and education. All of the services at her center are free to the community.

Rhondda Waddell, PhD, LCSW is a Full Professor in the School of Education and Social Services at Saint Leo University. Dr. Waddell has more than twenty years of social work and service-learning practice experience with the University of Florida ‘s Interdisciplinary Family Health program. As a professor she delights in the development of an ongoing relationship with students and community partners in collaborative service activities. She received both her PhD and MSW degrees from Florida State University. Dr. Waddell developed and teaches a Veterinary Social Work class, and works closely with her therapy dog, Andy.

Cathy D. Meade, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a Senior Member in the Division of Population Sciences, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, and provides leadership for a multitude of NCI-funded health disparities research and education activities. She is a nationally recognized expert in the areas of health disparities, cancer communications, literacy and cancer education, is well-versed in community based participatory methods and especially skilled in building and sustaining community partnerships.

Clement K. Gwede, PhD, MPH, RN is an Associate Member in the Department of Health Outcomes and Behavior, Division of Population Sciences at Moffitt Cancer Center, and Associate Professor in the Division of Oncologic Sciences at the University of South Florida College of Medicine. His research focuses on targeted interventions to reduce health disparities among medically underserved multi-ethnic/diverse populations and improve quality of life. His expertise includes community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods and client directed interventions to increase community access to colorectal and prostate screening and informed decision making.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Vani Nath Simmons, Email: Vani.Simmons@moffitt.org.

Lynne B. Klasko, Email: Lynne.Klasko@moffitt.org.

Khaliah Fleming, Email: Khaliah.Fleming@moffitt.org.

Alexis M. Koskan, Email: alexis.koskan@gmail.com.

Nia T. Jackson, Email: niaj@mail.usf.edu.

Shalewa Noel-Thomas, Email: ThomasSH@hillsboroughcounty.org.

John S. Luque, Email: jluque@georgiasouthern.edu.

Susan T. Vadaparampil, Email: Susan.Vadaparampil@moffitt.org.

Ji-Hyun Lee, Email: Ji-Hyun.Lee@moffitt.org.

Gwendolyn P. Quinn, Email: Gwen.Quinn@moffitt.org.

Lounell Britt, Email: lcbritt38@yahoo.com.

Rhondda Waddell, Email: Rhondda.Waddell@saintleo.edu.

Cathy D. Meade, Email: Cathy.Meade@moffitt.org.

Clement K. Gwede, Email: Clement.Gwede@moffitt.org.

References

- Braun KL, Tsark JAU, Santos LA, Aitaoto N, Chong C. Building Native Hawaiian capacity in cancer research and programming. Cancer. 2006;107(S8):2082–2090. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan DR, Miller FG, Wallerstein N. Ethical issues in community-based participatory research: balancing rigorous research with community participation in community intervention studies. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2007;1(2):153–160. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Foss C, Ellefsen B. The value of combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in nursing research by means of method triangulation. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;40(2):242–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwede CK, Menard JM, Martinez-Tyson D, Lee JH, Vadaparampil ST, Padhya TA, et al. Strategies for assessing community challenges and strengths for cancer disparities participatory research and outreach. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11(6):876–887. doi: 10.1177/1524839909335803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, Ciske S, Foley M, Fortin P, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors to sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisovicz N, Johnson RE, Higginbotham J, Downey JA, Hardy CM, Fouad MN, et al. The Deep South Network for cancer control. Cancer. 2006;107(S8):1971–1979. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque J, Martinez-Tyson D, Bynum S, Noel-Thomas S, Wells K, Vadaparampil S, et al. A social network analysis approach to understand changes in a cancer disparities community partnership network. Annals of Anthropological Practice. 2011;35(2):112–135. doi: 10.1111/j.2153-9588.2011.01085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay A, Ryan J. From the North American Primary Care Research Group: community needs assessment and development using the participatory research model. Annals of Family Medicine. 2003;1(3):183–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CD, Menard JM, Luque JS, Martinez-Tyson D, Gwede CK. Creating community-academic partnerships for cancer disparities research and health promotion. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12(3):456–462. doi: 10.1177/1524839909341035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(6):684–697. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Health Disparities Defined. 2010 http://crchd.cancer.gov/disparities/defined.html.

- Nguyen TT, McPhee SJ, Bui-Tong N, Luong TN, Ha-Iaconis T, Nguyen T, et al. Community-based participatory research increases cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese-Americans. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17(2 suppl):31–54. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. London: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scarinci IC, Johnson RE, Hardy C, Marron J, Partridge EE. Planning and implementation of a participatory evaluation strategy: a viable approach in the evaluation of community-based participatory programs addressing cancer disparities. Evaluation Program Planning. 2009;32(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg NE, Howell BM, Fields N. Community strategies to address cancer disparities in Appalachian Kentucky. Family & Community Health. 2012;35(1):31–43. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182385d2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanjasiri SP, Tran JH. Community capacity for cancer control collaboration: weaving an Islander network for cancer awareness, research and training for Pacific Islanders in Southern California. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2008;32(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Fujimoto K, Palmer P, Tanjasiri SP. A network assessment of community-based participatory research: linking communities and universities to reduce cancer disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(7):1319–25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Journal Information. 2010;100(S1) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore E. Understanding and Practicing Participatory Evaluation: New Directions for Evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Williams RL, Yanoshik K. Can you do a community assessment without talking to the community? Journal of Community Health. 2001;26(4):233–247. doi: 10.1023/a:1010390610335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]