Abstract

Objective

Inflammation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) is intimately linked to atherosclerosis and other vascular inflammatory disease. Thioredoxin interacting protein (Txnip) is a key regulator of cellular sulfhydryl redox and a mediator of inflammasome activation. The goals of the present study were to examine the impact of Txnip ablation on inflammatory response to oxidative stress in VSMC and to determine the effect of Txnip ablation on atherosclerosis in vivo.

Methods and results

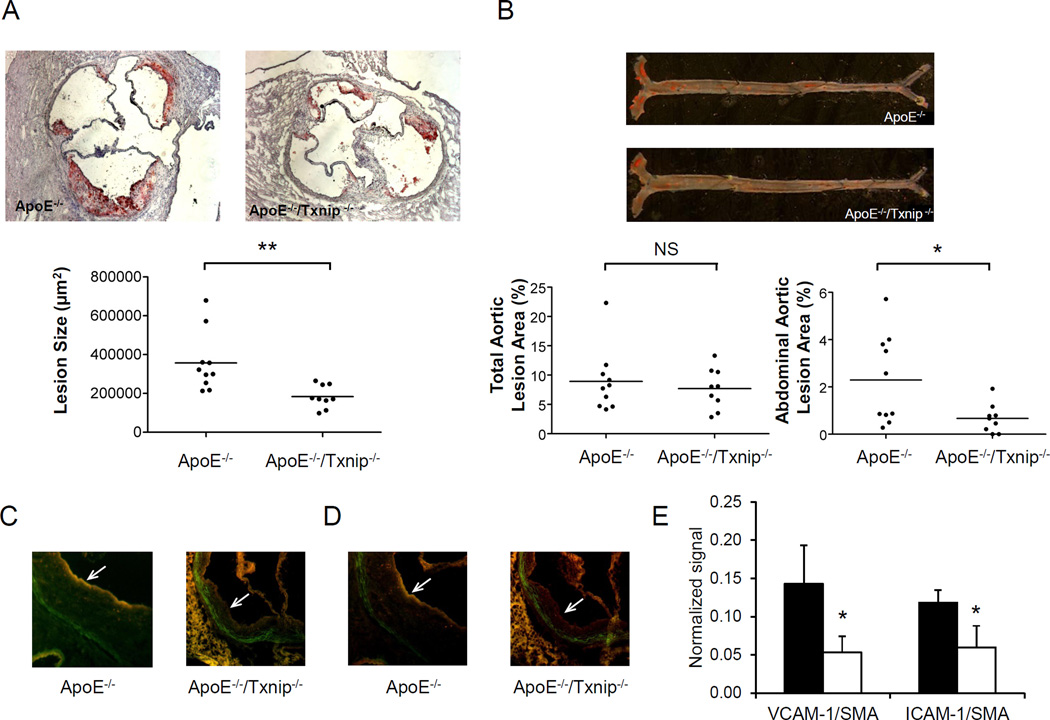

Using cultured VSMC, we showed that ablation of Txnip reduced cellular oxidative stress and increased protection from oxidative stress when challenged with oxidized phospholipids and hydrogen peroxide. Correspondingly, expression of inflammatory markers and adhesion molecules were diminished in both VSMC and macrophages from Txnip knockout mice. The blunted inflammatory response was associated with a decrease in NF-κB nuclear translocation. Loss of Txnip in VSMC also led to a dramatic reduction in macrophage adhesion to VSMC. In vivo data from Txnip-ApoE double knockout mice showed that Txnip ablation led to 49% reduction in atherosclerotic lesion in the aortic root and 71% reduction in the abdominal aorta, compared to control ApoE knockout mice.

Conclusion

Our data show that Txnip plays an important role in oxidative inflammatory response and atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. The atheroprotective effect of Txnip ablation implicates that modulation of Txnip expression may serve as a potential target for intervention of atherosclerosis and inflammatory vascular disease.

Keywords: inflammation, atherosclerosis, oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) are vital to the maintenance of vascular tone and play a critical role in many vascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, in-stent stenosis and aneurysms [1]. In response to vascular injury or oxidative stimuli, VSMC undergo a phenotypic change to a “proliferative, migrating and synthetic” state, characterized by excess extracellular matrix and inflammatory cytokine production with expression of adhesion molecules such as intercellular ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 [2]. Secretion of paracrine signals by activated VSMC promotes leukocyte infiltration into the damaged vessel wall (reviewed in [3]). These changes in VSMC contribute to atherosclerotic plaque growth and the formation of fibrotic cap, which stabilizes and prevents plaque rupture. Oxidation products of phospholipid 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine (oxPAPC) mimic the in vivo effects of minimally modified LDL [4]. In addition to inducing multiple proatherogenic changes in endothelial cells and macrophages [5], oxPAPC stimulates VSMC differentiation and proliferation [6–8]. These findings highlight the role of oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in atherogenesis.

Thioredoxin interacting protein (Txnip) was originally identified by yeast two-hybrid analysis as a negative regulator of thioredoxin-1 (Trx1) [9], a key determinant of cellular sulfhydryl redox homeostasis. We and others have demonstrated that Txnip modulates cellular glucose utilization and mitochondrial oxidation of metabolic fuels [10–14]. Txnip-null mice cannot survive prolong fasting and exhibit hypoglycemia, hyperketonemia and hypertrilgyceridemia [13]. Besides its involvement in cellular redox and energy metabolism, there is increasing evidence that indicates the importance of Txnip in vascular function and inflammation process. Genetic association studies showed that polymorphism affecting Txnip expression is linked to hypertension and arterial stiffness [15, 16]. Studies in endothelial cells showed that Txnip promotes inflammatory response in response to disturbed flow [17]. In addition, Txnip is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β production in cultured THP-1 cells [18]. However, the role of Txnip in VSMC inflammation is not well understood. Given the critical role of Txnip in redox homeostasis and inflammation, we hypothesize that ablation of Txnip expression would protect VSMC from oxidative stress and reduce inflammation. In the present study, we used VSMC isolated from TKO mice to investigate the effects of Txnip ablation on cellular redox status and inflammatory response. In addition, we also assessed the impact of Txnip on atherosclerosis in vivo. Our data shows that Txnip plays an important role in both VSMC inflammation and atherosclerosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Studies

Generation and characterization of Txnip knockout (TKO) mice were described previously [19]. TKO mice were bred with ApoE knockout mice (in C57BL/6 background) to generate heterozygous Txnip-ApoE double knockout (Txnip+/−/ApoE+/−) mice. Heterozygous mice were then inter-crossed to generate homozygous Txnip-ApoE double knockout (Txnip−/−/ApoE−/−) mice. Circulating monocytes profiling was carried out using the Heska (Loveland, CO) HemaTrue™ Veterinary Hematology Analyzer. Blood was collected in 20-µl heparin-coated glass capillaries and processed using standard procedures as per instructions from Heska. All procedures described were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California at Los Angeles.

Cell culture

Primary VSMC were isolated by enzymatic dissociation from the aortas of TKO and C57BL/6 mice and cultured in growth media as described previously [20]. The purity and identity of SMC were determined by immunohistochemical staining with smooth muscle–specific α-actin antibody (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA). All cells were positive for smooth muscle α-actin (SMA). In addition, expression levels of endothelial cell markers and smooth muscle markers were measured by quantitative real-time PCR to ensure the identity of SMC lineage. VSMC were grown to 100% confluence and then switched to serum-free media for 1 h. Cells were treated with OxPAPC (gift from Judith Berliner, 40 µg/ml) or H2O2 (0.4 mM) in DMEM containing 1% FBS for 4 h. All experiments were performed with VSMC at passages 5 to 9. Bone marrow-derived macrophages were isolated from the femur and tibia of C57BL/6 mice and cultured as described previously [21].

Measurement of cellular ROS levels

Cells were stained with 5 µM dihydroethidium (DHE) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Fluorescence of DHE was captured with a fluorescence microscope (excitation wavelength at 488 nm and emission wavelength at 585 nm) and quantified using ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and normalized to cell area.

Redox Western blot

Redox Western analysis of Trx-1 was performed as previously described [22]. Briefly, cells were lysed in cold G-lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 6M guanidine HCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 8.30) containing 50 mM iodoacetic acid [23]. Derivatized proteins were desalted and separated by native PAGE and Western blotted with anti-mouse Trx1 antibody (Cell Signaling). The intensity of bands corresponding to oxidized (Trxox) and reduced Trx1 ([Trxred]) was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH Bethesda, MD). Trx1 redox potential (Eh) was calculated from the ratio of oxidized to reduced Trx1 by using the Nernst equation with Eo (midpoint potential) = −254 mV at pH 7.4 and 25°C [23–25]:

where R = universal gas constant, T= absolute temperature and F = Faraday constant

Extraction of total RNA and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from VSMC using Trizol (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using ABI MultiScribe Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) as manufacturer’s instruction. SYBR Green-based quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa) on LightCycler® 480 Instrument II (Roche). The primers used were listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Macrophage adhesion assay

Macrophage-to-VSMC adhesion studies were performed as described previously with modifications [26]. Briefly, macrophages were labeled by incubating with BCECF-AM (1.6 µM) in PBS at 37°C for 30 min. Fluorescently labeled cells were washed twice with medium containing 1% FBS/DMEM. Macrophages (4×104 cells/well) were added to 24 wells containing confluent VSMC monolayers that were serum-starved for 1 hour and then treated with OxPAPC (40 µg/ml) or H2O2 (0.4 mM) for 4 hours. After incubation for 15 min at 37°C, medium was removed and VSMC layers with attached macrophages were gently washed twice with PBS. BCECF AM-labeled macrophages were observed under fluorescence microscope (Leica) and imaged by cold CCD camera after fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fluorescently labeled macrophages were analyzed and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH Bethesda, MD).

Subcellular fractionation of NFκB

Cytosolic and nuclear fractions were prepared using the NE-PER Nuclear Protein Extraction kit (Pierce) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Protein concentration was determined by BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce). Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each well and resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot analysis using specific antibody to NFκB (p65). Amount of protein in each sample was quantified by densitometry and normalized to that of lamin A/C (nuclear) or tubulin (cytosolic).

Histological analyses and quantification of atherosclerosis lesion

Hearts from 28 weeks old male mice were perfused with saline. Following cryo-embedding in OCT, serial cryosections were prepared through the ventricle until the aortic valves appeared. From then on, every fifth 10-µm section was collected on poly-d-lysine–coated slides until the aortic sinus was completely sectioned. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and oil red O, which specifically stains lipids. The lipid-staining areas on 25 sections, centered around aortic valves, were determined in a blinded fashion by light microscopy. The mean value of lipid staining areas of aortic wall per section was then calculated. To determine macrophage and smooth muscle cell content, cryo-sections were stained using antibodies against CD68 (Rat anti-mouse, AbD Serotec), or α-actin (Rabbit monoclonal Ab, Epitomics) followed by secondary antibody with HRP-tag (Biotinylated Anti-Rat IgG, mouse absorbed, #BA-4001, Vector Laboratories) and VECTOR Red (#SK5100, Vector Laboratories) using VECTASTAIN ABC-AP Kit (#AK-5000, Vector Laboratories). En face analyses of lesions in the entire aorta were performed according to procedures described by Tangirala et al. [27]. After perfusion-fixation, the aorta was dissected out, opened longitudinally from heart to the iliac arteries, pinned on a black wax pan, and stained with Sudan IV solution. The image of the aorta was captured using a SONY DXC-970MD color video camera, and the image analysis was performed using the Image-Pro plus program (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) in a blinded fashion. The area covered by atherosclerotic lesions divided by the area of the entire aorta was calculated and compared.

For immunohistochemical co-localization, aortic arch sections (fixed in cold acetone, and blocked with PBS containing 10% normal donkey serum and 1% BSA for 1 hr at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with rabbit anti-SMA (Abcam) primary antibody together with either goat anti-VCAM-1 (Santa Cruz Biotech.) or goat anti-ICAM-1 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotech.) for 1 hr at room temperature, which was followed by incubation with both Alexa Fluor 546 donkey anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then washed in PBS. The sections were mounted with Prolong Gold + DAPI (Cell Signaling) and observed with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. Images were captured with a Nikon Digital Sight DS-L1 camera using Image Pro-Plus 5.1 software and quantified using ImageJ software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). To compare the expression levels of VCAM-1/ICAM-1 in SMC in the lesion, fluorescence corresponding to VCAM-1/ICAM-1 (green) in lesion area co-localized with SMA was measured. Results were normalized to the amount of SMA to account for variations in SMC amount in different samples.

Statistical methods

All data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. Group mean values were compared by Student's two-tailed t test or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results with p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

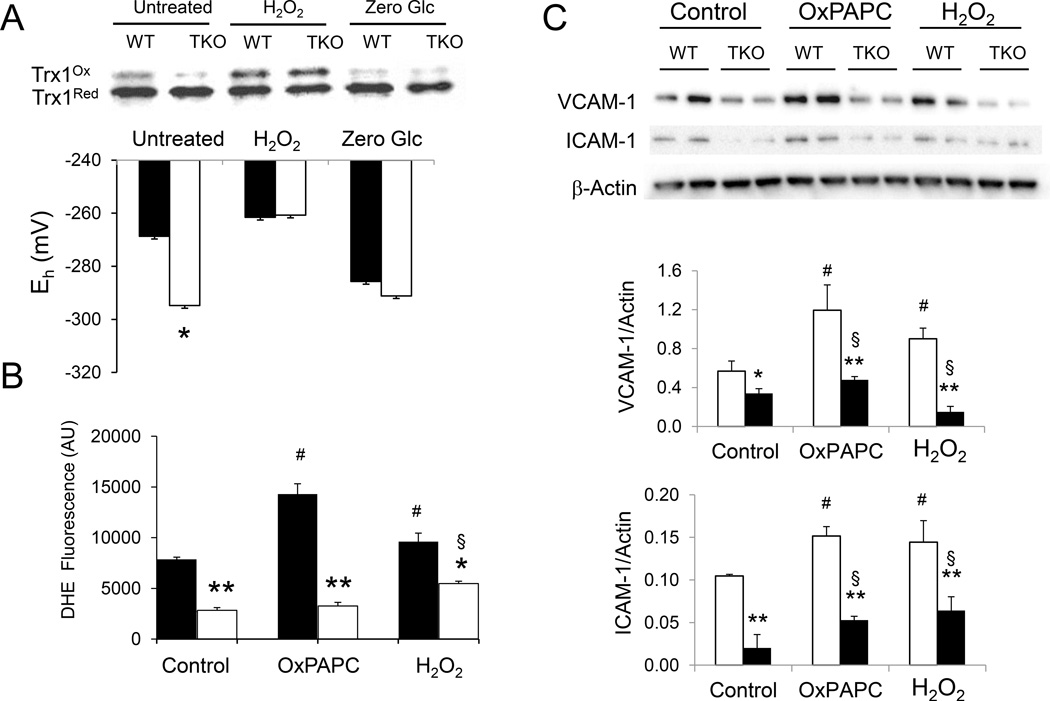

Txnip ablation decreases Trx1 oxidation and cellular ROS levels

The redox state of Trx1 in isolated VSMC was assessed by redox Western analysis [23]. The ratio of oxidized to reduced Trx1 was markedly decreased in cells deficient in Txnip. Trx1 redox potential (Eh) was 27.1 mV lower in TKO VSMC than that of WT cells (−267.7 ± 2.5 mV vs −294.8 ± 2.8 mV, WT and TKO cells respectively, Fig. 1A), indicating reduction of oxidized thiols by Trx1 is energetically more favorable in Txnip-null VSMC. This difference in redox potential was abolished when both cells were treated with excess oxidizing agent H2O2 (−261.6 ± 1.8 mV and −260.7 ± 2.4 mV, WT and TKO cells respectively, Fig. 1A). Conversely, when Txnip expression in cells was suppressed by zero glucose incubation [28], Trx1 redox potential of WT cells decreased to a level similar to that of TKO cells (−285.7 ± 3.0 V and −291.4 ± 2.5 mV, WT and TKO cells respectively, Fig. 1A). These data indicate that Txnip modulates cellular Trx1 redox potential and loss of Txnip promotes reduction of oxidized thiols by Trx1 in VSMC.

Figure 1. Txnip deficiency alters Trx1 redox potential and reduces cellular levels of ROS and inflammatory genes.

A. VSMC from WT (filled bars) and TKO (empty bars) mice were treated with H2O2 (0.4 mM) or cultured in zero glucose condition (Zero Glc) for 4 hours. Reduced and oxidized thioredoxin-1 were separated by native and non-reducing PAGE and detected by Western blotting. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software and redox potential (Eh) values were calculated using the Nernst equation. B. VSMC from WT (filled bars) and TKO (empty bars) mice were treated with OxPAPC (40 µg/ml) or H2O2 (0.4 mM) for 4 hours. Cellular ROS levels were measured by fluorescent staining with dihydroethidium (DHE). Positively stained cells were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH Bethesda, MD). Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C. Equal amounts of total cellular proteins were loaded in each lane and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Expression levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and β-actin were detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies (upper panel). Amount of protein were quantified and normalized to β-actin (lower panel). Data represent the mean ± S.D. (n=4). D–E. Total GSH (D) and GSH/GSSG ratio (E) were determined in WT and TKO cells. No significant difference was observed between the two groups. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. *denotes p<0.05 and ** denotes p<0.01 versus WT control in each treatment group whereas # represents p<0.05 versus untreated WT control and § represents p<0.05 versus untreated TKO control.

Under basal culture conditions, cellular level of ROS in TKO cells was reduced (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. S1). When challenged with oxPAPC or H2O2, DHE staining increased significantly in WT cells whereas the increase in DHE fluorescence was blunted in TKO cells. These data suggest ablation of Txnip reduces cellular ROS level and protects VSMC from oxidative stress. The decrease in oxidative stress in TKO cells was not due to increased expression of antioxidant genes (Supplementary Fig. S2A–D). No difference in total GSH levels or GSH/GSSG ratio was observed between WT and TKO VSMC under normal culturing conditions (Supplementary Fig. S2E & F), suggesting that protection against oxidative stress in TKO cells was independent to GSH redox capacity. Consistent with these findings, expression of the inflammatory genes VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 was markedly diminished in VSMC from TKO cells (Fig. 1C).

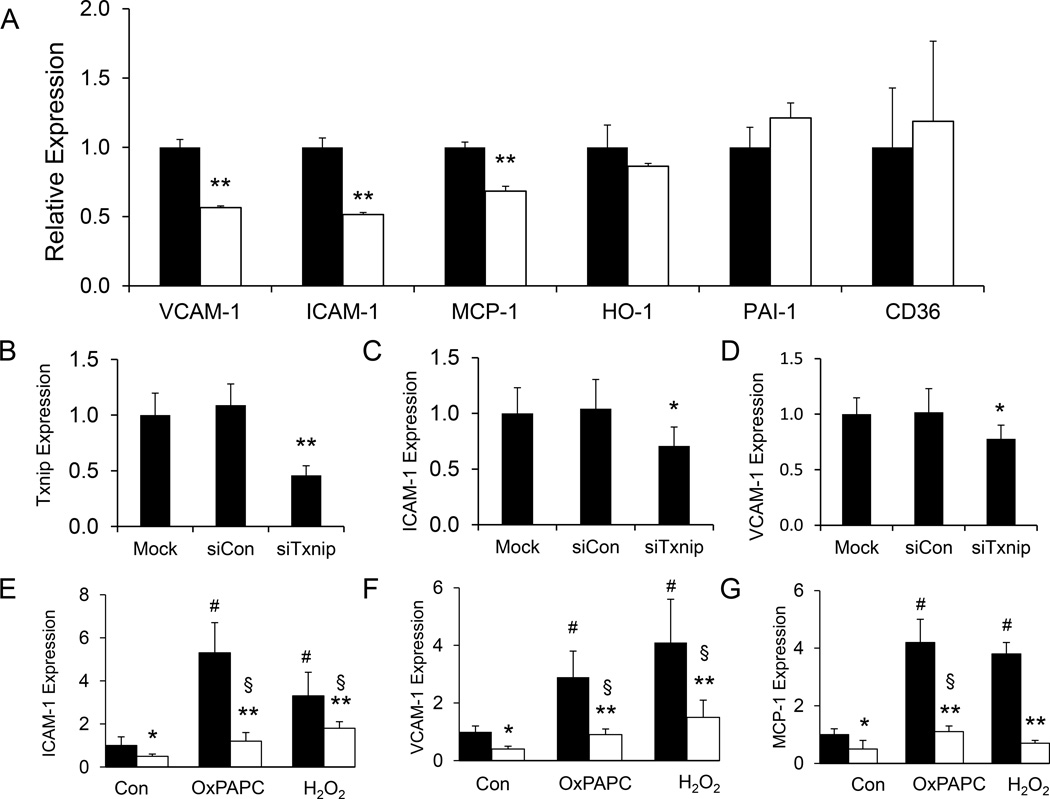

Decreased inflammatory response in VSMC from TKO mice

We examined if Txnip ablation would alter the expression of inflammatory markers in VSMC. Under basal culturing conditions, mRNA expression levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) were significantly reduced in TKO cells whereas no difference was observed in heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) (Fig. 2A). Knockdown of Txnip by siRNA (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. S3) reduced the expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 when compared to scramble siRNA controls (Fig. 2C & D, Supplementary Fig. S3), indicating that expression of these inflammatory markers are modulated by Txnip expression levels. When treated with OxPAPC or hydrogen peroxide, expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and MCP-1 in WT cells were significantly induced; however, this response was blunted in TKO cells (Fig. 2E–G).

Figure 2. Txnip ablation decreases inflammatory gene expression.

A. Total RNA was isolated from WT (filled bars) and TKO (empty bars) VSMC. Levels of mRNA expression were determined by real time PCR analysis using primers specific to VCAM-1, ICAM-1, MCP-1, HO-1, PAI-1, and CD36. Expression was normalized against β-actin expression. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. ** denotes p<0.01 versus WT control. B–D. WT VSMC were transfected with scramble control (siCon) siRNA or specific siRNA targeted to Txnip (siTxnip) for 48 hours. mRNA expression was normalized against β-actin expression. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of six independent experiments. *denotes p<0.05 and ** denotes p<0.01 versus mock-transfected control. E–G. VSMC from WT (filled bars) and TKO (empty bars) mice were treated with OxPAPC (40 µg/ml) or H2O2 (0.4 mM) for 4 hours. mRNA expression was normalized against β-actin expression. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of four independent experiments. *denotes p<0.05 and ** denotes p<0.01 versus WT control in each treatment group whereas # represents p<0.05 versus untreated WT control and § represents p<0.05 versus untreated TKO control.

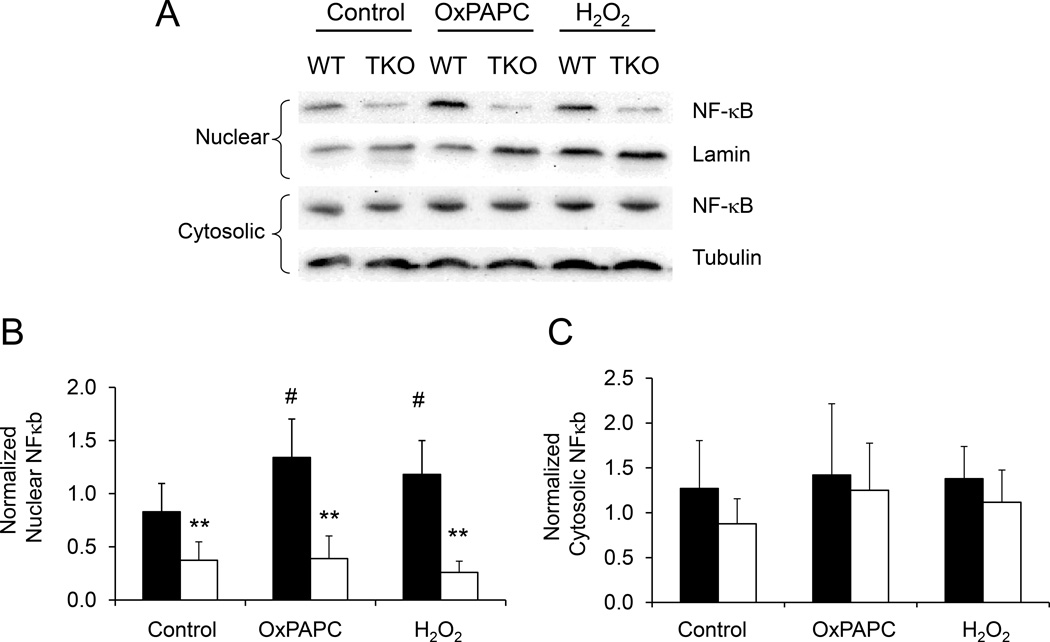

Txnip ablation decreased NF-κB nuclear translocation

It is well established that the redox-sensitive transcription factor NF-κB mediates the induction of a plethora of gene whose expression is involved in inflammation, including ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. Proinflammatory stimuli (e.g. oxidized LDL) activate the NF-κB signaling pathway. Previous studies demonstrated that increased Trx1 activity inhibits NF-κB activity [29]. The effect of NF-κB on gene transcription is dependent on its nuclear translocation. Although there was no significant difference in cytosolic NF-κB protein levels, nuclear NF-κB levels were markedly decreased in unstimulated TKO VSMC (Fig. 3). Compared to WT cells, nuclear NF-κB levels were markedly diminished in TKO cells when challenged with either oxPAPC or H2O2 (p < 0.05, Fig. 3B). These findings are consistent with our observation of diminished ROS levels and inflammatory marker expressions in TKO cells when stimulated by oxidative stress.

Figure 3. Txnip ablation decreases nuclear translocation of NF-κB.

A. VSMC were treated with OxPAPC (40 µg/ml) or H2O2 (0.4 mM) for 4 hours. Cellular proteins were subfractionated into cytosolic and nuclear fractions. Equal amounts of protein were resolved by 4–12% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. A representative blot is presented. B–C. Amounts of NF-κB protein in WT (filled bars) and TKO (empty bars) samples were quantified by densitometry and normalized to Lamin A/C (nuclear) or Tubulin (cytosolic). Relative protein expression in TKO cells compared to WT cells (set as 100% in each treatment group) is represented as mean ± S.D. (n=5). ** denotes p<0.01 versus WT control. whereas # represents p<0.05 versus untreated WT control.

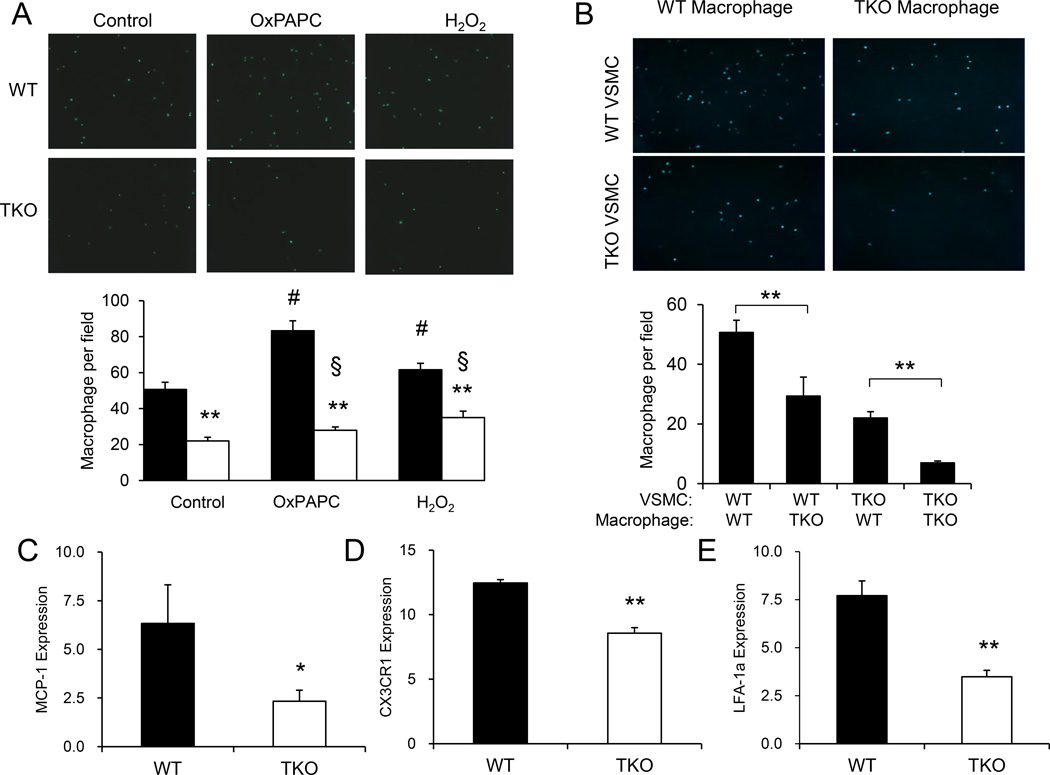

Txnip ablation reduced adhesion of macrophage to VSMC

Interaction between transmigrated monocytes and VSMC facilitates monocyte retention and plays an important role in regulating monocyte function within the vasculature in early atherosclerotic lesions [30–32]. Since adhesion molecule (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) expression was diminished in TKO cells, we tested if this would affect macrophage adhesion. When incubated with macrophages from WT mice, VSMC from TKO mice showed reduced levels of macrophage adhesion (Fig. 4A). While treatment with OxPAPC or H2O2 enhanced macrophage adhesion to VSMC from WT mice, TKO VSMC showed a markedly blunted response to these stimuli (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, when WT VSMC were incubated with macrophages from TKO mice, there was also a drastic reduction in the number of cells adhered, suggesting that macrophages from TKO also exhibit a lower propensity of adhesion (Fig. 4B) to VSMC. This assertion is supported by the observed further reduction in macrophage adhesion when VSMC from TKO mice were incubated with macrophages from TKO mice (Fig. 4B). To elucidate the underlying mechanism, we measured the expression levels of inflammatory markers and adhesion molecules and showed that CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1), lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1a) and MCP-1 were markedly reduced in macrophages from TKO mice (Fig. 4C) although expression of CX3CL1 in VSMC was not altered (Supplementary Fig. S4). In addition, no difference in the number of circulating monocytes was observed between WT (0.78 ± 0.23 × 103/µl) and TKO mice (0.53 ± 0.10×103/µl, p = 0.189). These data suggest reduction in pro-inflammatory and pro-adhesion molecule expression by Txnip ablation may contribute to the dramatic decrease in macrophage adhesion to VSMC.

Fig 4. Txnip ablation diminishes macrophage adhesion.

A. VSMC were treated with OxPAPC (40 µg/ml) or H2O2 (0.4 mM) for 4 hours. Fluorescently labeled macrophages were then incubated for 15 min and number of cell adhesion to WT (filled bars) and TKO (empty bars) VSMC was determined. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. ** denotes p<0.01 versus WT control in each treatment group whereas # represents p<0.05 versus untreated WT control and § represents p<0.05 versus untreated TKO control. B. VSMC from WT and TKO mice were incubated with macrophages from WT and TKO mice respectively. Number of cell adhesion to WT (filled bars) and TKO (empty bars) VSMC was determined. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. ** denotes p<0.01 versus WT control. C–E. Total RNA was isolated from WT (filled bars) and TKO (empty bars) macrophages. Levels of mRNA expression were determined by real time PCR analysis using primers specific to MCP-1, CX3CR1, and LFA-1a. Expression was normalized against β-actin expression. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. * denotes p<0.05 and ** denotes p<0.01 versus WT control.

Txnip ablation reduced atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice

To assess the impact of Txnip expression on atherosclerosis development in vivo, we cross bred TKO mice with atherosclerosis susceptible apolipoprotein E knockout (ApoE-KO, ApoE−/−) mice to generate Txnip-ApoE double knockout (DKO, Txnip−/−/ApoE−/−) mice. Mice were fed on chow diet and sacrificed at 28 weeks. The body weight of DKO mice was higher than that of ApoE-KO mice; however, adiposity (% body fat) was not different between the two groups (Supplementary Table S2). In addition, there was no significant difference in triglyceride, total cholesterol, cholesterol ester and HDL cholesterol levels between the two strains (Supplementary Table S2). However, plasma glucose and insulin were lower in DKO mice, similar to the hypoglycemia phenotype observed in fasting whole body TKO mice as reported previously [11, 12, 33]. Analysis of Oil Red O–stained aortic root lesions revealed that the absence of Txnip led to a significant reduction in lesion size. The mean atherosclerotic lesion size at the aortic root of DKO mice was 49% reduced comparing to that of apoE-KO mice (183,583 ± 58,732 µm2/section vs 357,175 ± 152410 µm2/section, Fig. 5A). No calcification was associated with any atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic sinus of these mice. En face analysis did not reveal any difference in the aortic arch and descending aorta; however, lesion area in the abdominal aorta was significantly reduced (71%) in DKO mice when compared to ApoE-KO mice (Fig. 5B). No significant difference in lesion composition was observed between the two groups of mice, as determined by CD68 and α-actin immunostaining respectively for macrophage and smooth muscle cells in the aortic sinus lesion area (Supplementary Fig. S5). Consistent with the findings in cultured VSMC, expression of VCAM-1 (Fig. 5C & E) and ICAM-1 (Fig. 5D & E) in the smooth muscle cells in the atherosclerotic lesion was reduced in DKO mice comparing to that of ApoE-KO mice. These data show that ablation of Txnip protects against the development of atherosclerosis.

Fig 5. Txnip ablation ameliorates atherosclerosis.

A. Morphometric evaluation of atherosclerotic lesion size in the aortic root of 28-week old male ApoE−/− and Txnip−/−/ApoE−/− mice. Oil red O-stained sections in representative animals are shown (upper panel) and quantified (lower panel). Horizontal lines represent means of individual data points. B. En face lesion area in ApoE−/− and Txnip−/−/ApoE−/− mice were analyzed. Oil red O-stained sections in representative animals are shown (upper panel) and quantified (lower panel). Horizontal lines represent means of individual data points. C–D. Immunohistochemical co-localization of smooth muscle actin (red) with VCAM-1 (green, C) or ICAM-1 (green, D) in the smooth muscle cap (indicated by arrows) of atherosclerotic lesion in ApoE−/− and Txnip−/− /ApoE−/− mice. E. Immunofluorescence of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in the atherosclerotic lesion area colocalized with SMA from ApoE−/− (filled bars) and Txnip−/−/ApoE−/− (empty bars) mice was measured and normalized to the fluorescence of SMA. Results are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 5). * denotes p<0.05 versus WT control.

DISCUSSION

Txnip is a key regulator of glucose utilization and fuel metabolism in skeletal muscle [19, 34, 35] and has recently emerged as a crucial mediator of inflammation [18]. Our findings show that Txnip also plays an important role in SMC redox and inflammatory response. Txnip ablation led to marked reduction in cellular ROS and increased Trx1 redox potential which is associated with blunted inflammatory response to oxidative stress and reduced NF-κB nuclear translocation. We also made a novel finding that Txnip ablation in VSMC diminished macrophage adhesion. Interestingly, macrophages from TKO mice also expressed decreased levels of pro-adhesion genes and exhibited dramatically reduced adhesion to VSMC. Using the atherosclerosis susceptible apoE-KO mouse model, we demonstrated for the first time that Txnip ablation reduced atherosclerosis in vivo and reduction in VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression in the smooth muscle cells in atherosclerotic lesion. Together, these data suggest Txnip plays an important role in oxidative stress response in VSMC and the development of atherosclerosis.

While transient fluctuations in ROS levels function as an important intracellular signal, uncontrolled accumulation of ROS could lead to free radical-mediated chain reactions that cause oxidative damage to cellular components [36]. ROS initiates peroxidation of phospholipids as well as sulfhydryl residues in proteins, which could subsequently alter normal physiological functions. To combat these deleterious effects, various antioxidant systems are in place to eliminate excessive ROS accumulation and protect against oxidative damage in cells. Txnip binds to reduced Trx1 and modulates Trx1 activity [37], which is crucial for reversing oxidative damage to protein sulfhydryl residues by ROS. Previous studies indicated that overexpression of Txnip reduced Trx1 activity and proliferation in VSMC [37]. In this study, we demonstrated that ablation of Txnip in VSMC had a beneficial effect in reducing oxidative stress, as evidenced by lower cellular ROS levels and increased reducing power of cellular Trx1. In line with our findings, studies using histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) showed that induction of Txnip expression diminished Trx1 activity, increased the Trx1 oxidation state, and led to elevated cellular ROS levels [38]. The effect of Txnip ablation on cellular redox appears to be specific to the thioredoxin system, as there was no change in GSH pool size or GSH oxidation status in VSMC from TKO mice. Furthermore, ablation of Txnip in VSMC did not increase the expression of other antioxidant genes, such as Prx, GPx and SOD.

The involvement of Txnip in NLRP3 inflammasome activation sparks new interest regarding its role in inflammation. In atherosclerotic lesions, OxLDL promotes VSMC transition into an inflammatory phenotype and propagates the local inflammatory response. Oxidized phospholipids, such as oxPAPC, are active components of minimally modified low density lipoprotein which could induce multiple proatherogenic events in endothelial cells, macrophages, and VSMC. Our study is the first to investigate the potential role of Txnip in VSMC inflammation response induced by oxidized phospholipids. Our results clearly demonstrated that Txnip ablation decreased cellular ROS levels and attenuated the stimulation of pro-inflammatory and pro-adhesion genes (ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and MCP-1) expression by oxPAPC and H2O2. Interaction of oxPAPC with free protein sulfhydryl was recently reported to play an important role in mediating the effects of oxPAPC [39]. The possibility that alteration in Trx1 and sulfyhydryl redox in TKO cells may contribute to the difference in response to oxPAPC induced inflammatory response remains to be explored.

In addition to macrophage adhesion onto endothelial cells, interaction between macrophage and VSMC are also important in the initiation of atherosclerosis which represents a key mechanism to prevent migrated moncytes from apoptosis and thus favor abnormal accumulation [30]. VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 are expressed by intimal SMC within the atherosclerotic blood vessels but not found in healthy SMCs. The reduction of adhesion molecules and chemokines expression in TKO VSMC suggests that Txnip ablation may diminish macrophage adhesion. In accordance with our findings of decreased VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and MCP-1 expression in Txnip-null VSMC, macrophage binding to VSMC from TKO mice was significantly reduced and the stimulation of macrophage adhesion by oxidative stress was also greatly attenuated. Since increased oxidative stress in the vasculature is linked to many diseases such as atherosclerosis, vascular injury, and diabetes [40], our findings implicate that modulating Txnip expression could potentially be beneficial in preventing or slowing the progression of these vascular diseases. The potential protective role of Txnip ablation in vascular inflammation is further supported by our additional finding that macrophages from TKO mice exhibited a lesser propensity to VSMC adhesion. Compared to WT macrophages, Txnip-null mactophages showed decreased adhesion to WT VSMC. When Txnip-null macrophages were incubated with Txnip-null VSMC, adhesion was dramatically reduced comparing to the WT VSMC and macrophages. Modulation of macrophage adhesion by Txnip could potentially be an interesting pharmacological target to intervene in atherosclerosis.

Previous reports showed that increased expression of Txnip in endothelial cells subjected to disturbed flow is required for leukocyte interaction with vessel walls [17]. Together with our findings from VSMC and macrophages, these data strongly suggest that decreased Txnip expression may protect against atherosclerosis. Using the hyperlipidemic ApoE-KO mouse model, our study demonstrates for the first time that Txnip ablation ameliorates atherosclerosis in vivo, indicating that reduced Txnip expression is atheroprotective. The mechanisms by which Txnip alters atherosclerosis may be complicated. As Txnip is ubiquitously expressed and its expression has dramatic impact on both the metabolic [13, 19, 41–43] and inflammatory [17, 44–47] pathways, the atheroprotective effect observed in the present study is likely a consequence of distinct actions of Txnip in multiple tissue/cell types. The relative contribution by individual cell types remains to be resolved by future studies such as bone maroow transplant and cell-type specific Txnip knockout mice. While we observed a dramatic decrease in lesion size, there was no difference in the composition of SMC and macrophages. Recent studies suggest that macrophages turn over rapidly in murine atherosclerotic lesions [48]. The amount of macrophage in advanced lesions is dependent predominately on macrophage proliferation rather than monocyte influx [48]. It is possible that the lack of difference in macrophage composition in the lesion could be due to the fact that Txnip affects monocyte recruitment and retention in early atherosclerotic development but has lesser effect on macrophage proliferation at the later stage.

Txnip expression is increased in diabetic subjects who also have elevated risk of atherosclerosis. Previous studies showed that reducing expression of Txnip enhanced glucose uptake by skeletal muscle and improved glycemic control [19], suggesting inhibition of Txnip could be a potential means to intervene in diabetes. Results from this study have further clinical and therapeutic implications that Txnip ablation could provide additional beneficial effects by reducing vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis in diabetics. In summary, our data suggest Txnip plays an important role in vascular inflammation and in the development of atherosclerosis. Modulation of Txnip expression could be a potential therapeutic strategy to combat these diseases.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

-

Txnip ablation decreases oxidative stress in VSMC

-

-

Absence of Txnip attenuates inflammatory response to oxidative stress in VSMC

-

-

Loss of Txnip in VSMC leads to dramatic reduction in macrophage adhesion to VSMC

-

-

Txnip deficiency protects against atherosclerosis in ApoE-knockout mice

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Judy Berliner and Jim Springstead for providing oxPAPC for this study.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK080339 to STH.

Abbreviations

- Txnip

Thioredoxin Interacting Protein

- WT

wild type

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cells

- TKO

Txnip knockout

- Trx

thioredoxin

- DHE

dihydroethidium

- Eh

redox potential

- E′0

midpoint potential

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- oxPAPC

oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-p hosphorylcholine

- Prdx

peroxiredoxin

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- CD36

Cluster of Differentiation 36

- SMA

smooth muscle actin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(3):767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien KD, et al. Neovascular expression of E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in human atherosclerosis and their relation to intimal leukocyte content. Circulation. 1996;93(4):672–682. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raines EW, Ferri N. Thematic review series: The immune system and atherogenesis. Cytokines affecting endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vascular disease. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(6):1081–1092. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochkov VN, et al. Oxidized phospholipids stimulate tissue factor expression in human endothelial cells via activation of ERK/EGR-1 and Ca(++)/NFAT. Blood. 2002;99(1):199–206. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furnkranz A, et al. Oxidized phospholipids trigger atherogenic inflammation in murine arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(3):633–638. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000153106.03644.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heery JM, et al. Oxidatively modified LDL contains phospholipids with platelet-activating factor-like activity and stimulates the growth of smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(5):2322–2330. doi: 10.1172/JCI118288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherepanova OA, et al. Oxidized phospholipids induce type VIII collagen expression and vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ Res. 2009;104(5):609–618. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pidkovka NA, et al. Oxidized phospholipids induce phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells in vivo and in vitro. Circ Res. 2007;101(8):792–801. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.152736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishiyama A, et al. Identification of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D(3) up-regulated protein 1 as a negative regulator of thioredoxin function and expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(31):21645–21650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andres AM, et al. Diminished AMPK signaling response to fasting in thioredoxin-interacting protein knockout mice. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(8):1223–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chutkow WA, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein (Txnip) is a critical regulator of hepatic glucose production. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(4):2397–2406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui TY, et al. Mice lacking thioredoxin-interacting protein provide evidence linking cellular redox state to appropriate response to nutritional signals. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(23):24387–24393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oka S, et al. Impaired fatty acid utilization in thioredoxin binding protein-2 (TBP-2)-deficient mice: a unique animal model of Reye syndrome. Faseb J. 2006;20(1):121–123. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4439fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheth SS, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein deficiency disrupts the fasting-feeding metabolic transition. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(1):123–134. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400341-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira NE, et al. Thioredoxin interacting protein genetic variation is associated with diabetes and hypertension in the Brazilian general population. Atherosclerosis. 2012;221(1):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvim RO, et al. Thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP) rs7212 polymorphism is associated with arterial stiffness in the Brazilian general population. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26(5):340–342. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang XQ, et al. Thioredoxin interacting protein promotes endothelial cell inflammation in response to disturbed flow by increasing leukocyte adhesion and repressing Kruppel-like factor 2. Circ Res. 2012;110(4):560–568. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou R, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(2):136–140. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui ST, et al. Txnip balances metabolic and growth signaling via PTEN disulfide reduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(10):3921–3926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800293105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byon CH, et al. Oxidative stress induces vascular calcification through modulation of the osteogenic transcription factor Runx2 by AKT signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(22):15319–15327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800021200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byon CH, et al. Runx2-upregulated receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand in calcifying smooth muscle cells promotes migration and osteoclastic differentiation of macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(6):1387–1396. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.222547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Go YM, Jones DP. Thioredoxin redox western analysis. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2009;Chapter 17(Unit17):12. doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx1712s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halvey PJ, et al. Compartmental oxidation of thiol-disulphide redox couples during epidermal growth factor signalling. Biochem J. 2005;386(Pt 2):215–219. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson GN. Thiol regulation of the thylakoid electron transport chain--a missing link in the regulation of photosynthesis? Biochemistry. 2003;42(10):3040–3044. doi: 10.1021/bi027011k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson WH, et al. Redox potential of human thioredoxin 1 and identification of a second dithiol/disulfide motif. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(35):33408–33415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng L, et al. Diabetic conditions promote binding of monocytes to vascular smooth muscle cells and their subsequent differentiation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(3):H736–H745. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00935.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tangirala RK, Rubin EM, Palinski W. Quantitation of atherosclerosis in murine models: correlation between lesions in the aortic origin and in the entire aorta, and differences in the extent of lesions between sexes in LDL receptor-deficient and apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 1995;36(11):2320–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minn AH, Hafele C, Shalev A. Thioredoxin-interacting protein is stimulated by glucose through a carbohydrate response element and induces beta-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2005;146(5):2397–2405. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schenk H, et al. Distinct effects of thioredoxin and antioxidants on the activation of transcription factors NF-kappa B and AP-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(5):1672–1676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cai Q, Lanting L, Natarajan R. Interaction of monocytes with vascular smooth muscle cells regulates monocyte survival and differentiation through distinct pathways. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(12):2263–2270. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000146552.16943.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikeda U, et al. Monocyte-vascular smooth muscle cell interaction enhances nitric oxide production. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37(3):820–825. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Y, et al. Interaction between monocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells enhances matrix metalloproteinase-1 production. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36(2):152–161. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oka S, et al. Thioredoxin binding protein-2/thioredoxin-interacting protein is a critical regulator of insulin secretion and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor function. Endocrinology. 2009;150(3):1225–1234. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parikh H, et al. TXNIP regulates peripheral glucose metabolism in humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4(5):e158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muoio DM. TXNIP links redox circuitry to glucose control. Cell Metab. 2007;5(6):412–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(1):47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulze PC, et al. Vitamin D3-upregulated protein-1 (VDUP-1) regulates redox-dependent vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through interaction with thioredoxin. Circ Res. 2002;91(8):689–695. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000037982.55074.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ungerstedt J, et al. In vivo redox state of human thioredoxin and redox shift by the histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(11):2002–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Springstead JR, et al. Evidence for the importance of OxPAPC interaction with cysteines in regulating endothelial cell function. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(7):1304–1315. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M025320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forstermann U. Oxidative stress in vascular disease: causes, defense mechanisms and potential therapies. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5(6):338–349. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein deficiency induces Akt/Bcl-xL signaling and pancreatic beta-cell mass and protects against diabetes. Faseb J. 2008;22(10):3581–3594. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-111690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chutkow WA, et al. Deletion of the {alpha}-Arrestin Protein Txnip in Mice Promotes Adiposity and Adipogenesis While Preserving Insulin Sensitivity. Diabetes. 2010;59(6):1424–1434. doi: 10.2337/db09-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Debalsi KL, et al. Targeted Metabolomics Connects Thioredoxin-interacting Protein (TXNIP) to Mitochondrial Fuel Selection and Regulation of Specific Oxidoreductase Enzymes in Skeletal Muscle. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(12):8106–8120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.511535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamawaki H, et al. Fluid shear stress inhibits vascular inflammation by decreasing thioredoxin-interacting protein in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(3):733–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Gayyar MM, et al. Thioredoxin interacting protein is a novel mediator of retinal inflammation and neurotoxicity. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(1):170–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe R, et al. Anti-oxidative, anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory actions by thioredoxin 1 and thioredoxin-binding protein-2. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;127(3):261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perrone L, et al. Thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP) induces inflammation through chromatin modification in retinal capillary endothelial cells under diabetic conditions. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221(1):262–272. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robbins CS, et al. Local proliferation dominates lesional macrophage accumulation in atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19(9):1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/nm.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.