Abstract

Interventions for HIV prevention among female sex workers (FSWs) in China focus on HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) and individual behaviour change. An occupational health framework facilitates intervention across an array of health issues FSWs face including HIV/STI, violence, reproductive health, stigma and substance use. Through a case study of a community-based Jiaozhou (JZ) FSW programme, we developed a conceptual framework incorporating global discussions of structural approaches to HIV prevention with the specific social and structural contexts identified among FSWs in China. Based on ethnographic fieldwork between August 2010 and May 2013, we describe the evolution of this programme to its current occupational health focus and unpack the intervention strategies. We describe the critical features of the programme that have fostered success among FSWs including high-quality clinical services provided within a welcoming setting, responsive outreach work through staff and trained FSW peers, interpersonal and community-level engagement aimed at changing the local social and structural environments of sex work and tailored health education materials. This intervention differs from other projects in China by adopting a more holistic approach to FSW health that incorporates social issues. It also demonstrates the feasibility of structural interventions among FSWs even within an environment that has strong anti-prostitution policies.

Keywords: structural approach, female sex workers, China, HIV, STI

Introduction

Female sex workers (FSWs) in China: social and behavioural studies and HIV prevention strategies

Female sex work has a long-standing history in China as an integrated facet of social and economic life (Hershatter, 1997; Pan, 1997). Sex work became more visible in China starting in the late 1980s due to regular, government-ordered anti-prostitution crackdowns and growing epidemics of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs; Chen, Peeling, Yin, & Mabey, 2011). While HIV prevalence measured among FSWs at government sentinel surveillance sites is under 1% (Ministry of Health of People’s Republic of China, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization, 2011), a 2012 meta-analysis estimated HIV prevalence of 3% among FSWs in some parts of China (Baral et al., 2012). Sex work in China takes a wide diversity of forms, from women who are provided for as ‘second wives’, to those who seek clients in parks and other public spaces (Huang, Henderson, Pan, & Cohen, 2004). The form of sex work matters, as greater HIV/STI risk behaviours have been documented among low-tier FSWs such as those working as ‘street standers’ and in small karaoke bars (Wang et al., 2012).

An increasing number of studies document environmental and structural factors that influence HIV/STI risk in the context of sex work, including poverty, anti-prostitution and health policies, sex work setting and organisations, social mobility, gender-based violence and sexual and gender norms (Choi, 2011; Choi & Holroyd, 2007; Huang, 2010; Huang, Henderson, Pan, & Cohen, 2004; Huang, Maman, & Pan, 2012; Kaufman, 2011; Tucker, Ren, & Sapio, 2010; Tucker et al., 2011; Yi et al., 2012). These social and structural drivers of HIV/STI impact a range of occupational health and safety issues that go beyond HIV/STI to include the wide array of concerns that threaten the everyday life and work of women involved in sex work, including violence from clients and police, reproductive health needs, keeping sex work hidden from family, heavy alcohol drinking and exposure to drugs.

Despite the need to address social and structural factors, to date, most practical intervention work in China has focused primarily on individual behaviour change (China CDC, 2004; Hong & Li, 2009; Hong, Poon, & Zhang, 2011). Some efforts have been made at the health policy level, such as building a multi-sectoral working committee with involvement of community-based organisations (CBOs) and FSW peer educators (Kang et al., 2013; Lu, Zhang, Gu, & Feng, 2008; Wang et al., 2012). However, the main body of intervention work focuses on increasing HIV/STI knowledge, testing and condom use through health education trainings, venue-based testing and condom distribution (China CDC, 2004; Hong et al., 2011). A closer examination of the influence of social and structural factors on HIV/STI risk within commercial sex is needed.

Structural approach to prevent HIV/STI among FSWs: a framework applied to the Chinese context

In a global context, we have made great advances in biomedical prevention (Cohen et al., 2013) and notable efforts developing and testing behavioural interventions (Coates, Richter, & Caceres, 2008). Yet successful structural interventions remain elusive (Gupta, Parkhurst, Ogden, Aggleton, & Mahal, 2008). Structural approaches, as described by Auerbach, Parkhurst, and Cáceres (2011, p. 293), aim to ‘modify social conditions and arrangements by addressing the key drivers of HIV vulnerability that affect the ability of individuals to protect themselves and others from acquiring or transmitting HIV infection’, and these approaches should ‘foster individual agency … create and support AIDS-competent communities, and build health-enabling environments’. The term ‘structural’ may be interpreted in various ways; however, it is widely accepted that a structural approach for HIV prevention typically involves at least one of the following: effecting policy or legal changes; enabling environmental changes; shifting harmful social norms; catalysing social and political change; and empowering communities and groups (Adimora & Auerbach, 2010; Auerbach, 2009). A structural approach recognises that societal-level factors such as poverty, gender power relationship, social norms, social networking and policies are critical underlying drivers of the global HIV epidemic (Auerbach, Parkhurst, & Cáceres, 2011). Interventions to address societal-level factors can target the macro level, such as policy change and poverty alleviation, which require long-term efforts. Social drivers can also be addressed at the individual, interpersonal and community levels, through combination approaches with behavioural or medical interventions targeted at individuals (Auerbach, Parkhurst, & Cáceres, 2011; Gupta et al., 2008).

An intentional structural approach to working with FSW can be operationalised by addressing the local underlying social drivers of risk and employing combined multi-level intervention efforts. Empirical examples such as the Sonagachi FSW project in India illustrate that implementing HIV prevention with a structural focus is feasible when the social drivers of HIV (e.g. lack of female empowerment, gender norms) and structural contexts (e.g. anti-prostitution policies, poverty) are identified and addressed in a tailored way for the needs and contexts of the target community (Biradavolu, Burris, George, Jena, & Blankenship, 2009; Cornish & Ghosh, 2007; Rekart, 2005; Swendeman, Basu, Das, Jana, & Rotheram-Borus, 2009). The field of public health needs more examples of structural-level HIV prevention approaches involving FSW to enrich and expand global dialogue and action.

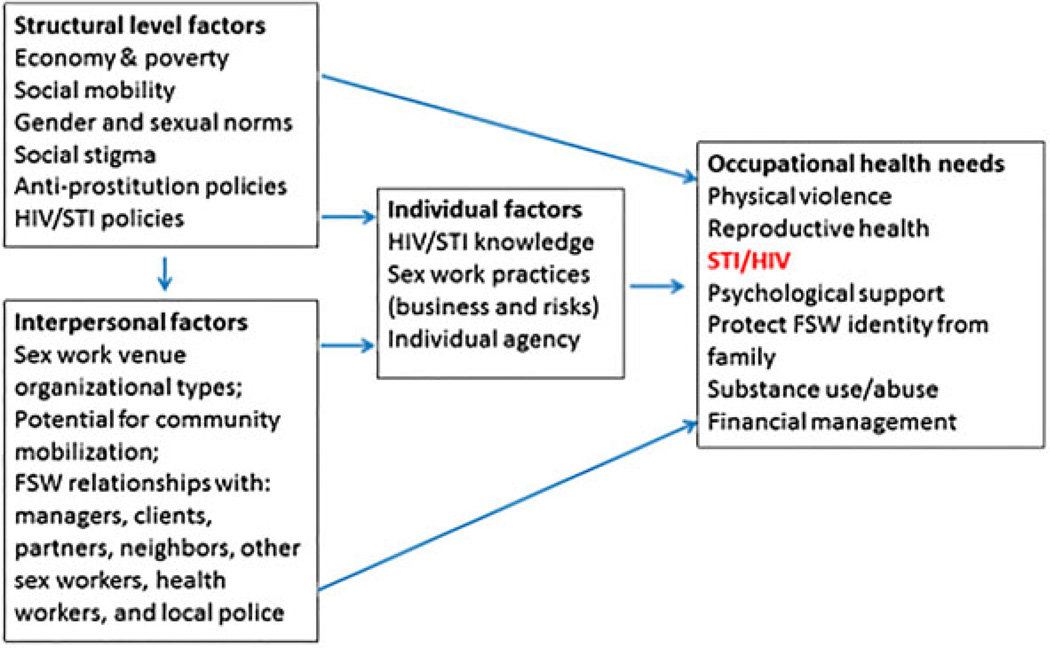

Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework that incorporates the global discussions around structural approaches to HIV prevention with the specific social and structural contexts and factors identified among FSWs in China. In this manuscript we illustrate this conceptual framework through a case study of a community-based FSW programme in China, which exemplifies an alternative approach to the traditional individual behaviour-level intervention model. We describe how the development and evolution of this programme organically came to take a more social and structural approach and unpack the components and strategies that have evolved to address specific social and structural factors through this programme.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of structural approach on HIV intervention among FSWs in China.

Methodology

We present this case study of the Jiaozhou (JZ) FSW programme to describe in detail the programme development and key intervention components. We present this as a new model of a structural-level approach to working with FSW in China that could be adapted, enhanced and tested in other Chinese and global settings. We used a multi-method ethnographic approach that built upon the first author’s 10-year working relationship with the director of the project (Dr Z) in order to understand the JZ programme through various activities, including workshops, in-depth fieldwork, interviews and intervention process and outcome evaluations.

Between August 2010 and May 2013 the first author conducted 30 days of fieldwork with the JZ programme. Fieldwork activities included: (1) observations at the programme site and outreach activities (e.g. flow of participants within the programme site, interaction between staff and participants and among participants, procedures and environment of outreach work settings); (2) participation in social activities hosted by the organisation that included programme staff, FSWs and in some cases family members and police who worked with the organisation; (3) multiple in-depth interviews with key programme staff including the director; and (4) review of relevant programme materials (e.g. HIV/STI Information, Education and Communication [IEC] material, clinic records, case studies and outreach workers’ fieldwork logs).

At the end of each fieldwork day the first author expanded detailed notes from that day’s interviews, group discussions and observations. As the project progressed, the first author used an iterative process to guide continued data collection and model development by regularly conducting feedback sessions with the director, key staff, FSW and the project funder.

A case study of JZ FSW programme in China

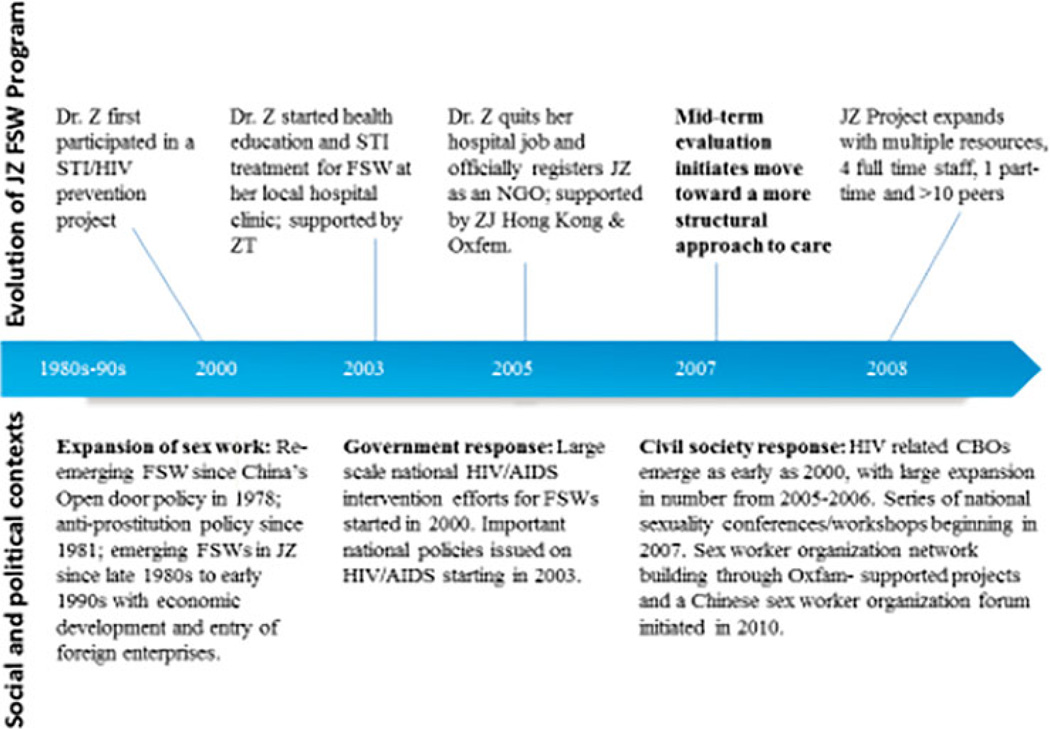

The JZ FSW programme is a CBO that serves FSW of JZ City using an occupational health and peer-leader model that includes the provision of individual-level medical and psychosocial services, and community-level advocacy and outreach efforts. As illustrated in Figure 2, the evolution of the JZ programme (events above the bar) occurred within specific social, political and epidemic contexts (events below the bar). The selected events listed below the bar provided opportunities or network support to the JZ programme. For instance, the emerging HIV/STI epidemics and related health policies of the late 1990s (Wu, Sullivan, Yang, Rotheram-Borus, & Detels, 2007) provided an umbrella under which to establish an FSW-focused CBO even within an anti-prostitution political context. In recent years, national-level FSW workshops and sexuality conferences with a rights-based approach have included CBO programme staff, FSW peers, researchers and FSW-friendly lawyers. In addition to information exchange and idea generation, these events strengthen the multi-sectoral relationships that are needed for successful structural interventions. In recent years, emerging HIV-focused CBOs and the networking among these CBOs also provided an enabling environment for community-based health interventions – including the JZ programme – and provided invaluable, direct intellectual and social support for continued programme development. JZ programme staff emphasised the importance of this social support when working on politically sensitive and socially stigmatised issues such as HIV and sex work.

Figure 2.

JZ FSW programme development process in context.

Programme development process and contexts

Programme development and initiation: 2000–2005

The first phase of the JZ programme could be characterised as following a typical individual-level approach to FSW intervention within China via provision of education, information and promotion of standard HIV/STI services. Dr Z started HIV/STI prevention work in 2000 while she participated in a larger-regional project for HIV/STI intervention among FSWs. Prior to this work, she had encountered women at her hospital clinic whom she identified as FSW. As she recalled, ‘There were a lot of xiaojie (FSW) in this city starting in the late 1980s. The sex industry reached its peak in the early 1990s, which was famous nationwide’. The Chinese Government began large-scale HIV intervention work around the year 2000 but had limited experience working with groups at high risk such as FSW. At this time, Dr Z began using her time outside of work to conduct door-to-door outreach in a remote area of the city that was famous for small roadside FSW venues. She recalled her shock at the large number and poor working conditions of these women.

An essential catalyst for Dr Z in developing the JZ FSW programme also came in 2000 when she met with staff from Ziteng, a Hong Kong-based CBO working with FSW. Supported by Ziteng, Dr Z started her first independent project in 2003 providing HIV/STI education, condoms and STI treatment services to FSW through outreach work and referring them to the hospital clinic where she worked. However, these activities caused conflicts between Dr Z and her medical colleagues due to the stigmatising perception of xiaojie as women with bad moral reputations and because of the reduced service prices she charged these women. As a result, in 2005, Dr Z retired early from her state-owned hospital job and officially registered a clinic-based CBO co-funded by Ziteng and Oxfam Hong Kong to focus on intervention work among FSWs. She also persuaded three people from the government clinic where she had been working to join the new CBO: a retired hospital worker responsible for testing, an administrative and staff management specialist and a clinic nurse. In addition, one FSW with whom they had built a good relationship was trained to work as a part-time peer educator.

Model shift: 2007 progress evaluation

During JZ’s programme development phase, the funding agencies (Ziteng and Oxfam) provided vital financial and technical support for the development of the community-based programme. The programme recognised that publically advocating for FSWs’ rights is politically sensitive in China and negotiation between non-profit organisations, communities and government is extremely rare. As such, the programme grounded its agenda in the local community and focused on providing services and mobilising FSWs and managers to address occupational health. Similar to most HIV/STI prevention and care efforts in China, JZ’s primary project activities began with standard health education, STI testing and treatment. However, a significant shift happened in 2007 after Ziteng conducted a progress evaluation. As Dr Z recalled:

We thought we were doing a great job delivering health education material, condoms and providing STI treatment; we didn’t stigmatize these women, we made so many efforts and devoted ourselves to the work; but then the director of Ziteng critically pointed out that our work strategy was problematic. I was totally shocked, confused and saddened. I even cried …. They asked me how these interventions worked, what were the issues threatening women’s lives here …. They went out to do outreach work together with us, and used examples arising on-site to push us to think and notice how the issues such as violence or being robbed might influence women’s acceptance of health education …. They also pushed me to talk with women about sex and provide training on how to use your mouth to put on a condom, which was totally out of my mind at that time!

This external evaluation conducted by Ziteng helped Dr Z and the JZ team to shift their approach from a traditional information, education and condom-promotion strategy to a more occupational health-centred focus that could facilitate recognising and addressing the social and structural contexts of sex work. As described later in the paper, this shift guided the efforts that became the main activities of the JZ programme.

Programme expansion: 2008–2013

Since its inception, the JZ programme has significantly expanded its intervention team, activities and networking with other national and international groups. Since 2008, the programme has received additional funding from the Gates Foundation and the Global Fund. Dr Z’s team began cooperating with Chinese and foreign universities on HIV/STI interventions among FSWs, and JZ became a training centre for other programme staff to learn how to work effectively with FSW. As of 2013, JZ had 4 full-time staff, 1 part-time staff and over 10 FSWs who work part-time as peer educators. Programme activities have expanded since 2008, especially for outreach work, such as distributing a newsletter and increasing the number of on-site trainings on HIV/STI education and addressing gender-based violence. Social support and community engagement activities have also increased, including visiting FSW re-education centres, increasing the frequency of FSW self-support group activities and increasing the number of FSW peer educators.

The remainder of this manuscript describes the JZ programme as of 2013, reflecting the changes of programme activities in approach and scope following the external evaluation of 2007 and the expansion activities of 2008–2013.

Key components and strategies of the JZ FSW programme

Addressing HIV/STI within an occupational health framework

The ultimate target of the JZ programme is FSW’s occupational health. HIV/STIs are positioned as one component among a series of occupational health issues that reflect the key structural factors women face in sex work, such as anti-prostitution laws, violence, social stigma and reproductive health problems. Women’s occupational health needs vary with time: some are more common and stable over time (e.g. violence, reproductive health and stigma), while others are newly emergent issues (e.g. increased drug use, intensified police crackdowns on sex work since 2010).

JZ’s main intervention activities take the form of tailored, high-quality clinical services provided directly to women within a welcoming clinic setting, responsive outreach work through staff and trained FSW peer leaders, interpersonal and community-level engagement aimed at changing the local social and structural environments of sex work and tailored IEC materials. Each set of activities targets different FSW occupational health issues as well as many of the structural and social factors illustrated in Figure 1. All activities contribute to the relationship building between FSW and the programme and overall success of the programme. Ultimately, these activities delivered within an occupational health framework result in greater trust between FSW and JZ programme staff and more supportive local environments to facilitate the work of JZ programme staff and foster the health and safety of FSW. We describe each of these main activities and cross-cutting themes below.

Core programmatic activities

A welcoming clinic setting and high-quality clinical services

FSWs face the dual stigma of HIV/STI and sex work, creating barriers to seeking and receiving medical care. JZ provides a safe physical and social space for FSW to see doctors and share their lives. The JZ clinic and activity centre are located in a discrete, convenient area within the city. This centre was intentionally designed for comfort: a clean, warm environment, a reception desk at the entrance, plants and decorations, a television and two massage beds at the back of the first floor. On the second floor, an outside room is used as a waiting room. The walls are decorated with IEC materials and notes written by FSW with wishes and ‘words from the heart’. Practical tips for women are also posted, such as an example of counterfeit money (a common problem in China) with a description of how to identify it. A round table and drinking water are always set out for chatting. Separated from the waiting room, an inner room is outfitted with a clean bed and standard medical facilities for physical exams, STI testing and treatment.

The clinic is reserved especially for FSW and is not open to the public. As Dr Z noted, this allows the clinic to offer a safe, confidential space – a feature that was highly valued by the FSW we interviewed. FSWs come to the clinic through outreach contact and introduction by other FSW. Women were also mobilised to bring new FSW and their regular partners (boyfriends, regular male clients) for STI treatment. The welcoming environment and high quality of clinic service, as illustrated below, made JZ clinic well known via word of mouth among the local FSW community. In addition, to avoid being recognised as the ‘FSW clinic’, which might bring stigma upon clientele, Dr Z named the clinic the ‘JZ Love and Health Consultation Centre’.

Within the welcoming clinic environment, JZ staff provides high-quality reproductive and gynaecological services including physical exams and blood testing for syphilis and HIV. When the JZ clinic first opened, services were provided free of charge. Later, a basic fee-for-service plan (e.g. 3–4 USD/blood test for STI) was implemented in order to foster FSWs’ self-responsibility to care about their health and to support the financial sustainability of the project.

Dr Z is a trained expert in STI and gynaecology. According to her, ‘you must know your own body well, rather than only focusing on getting the disease cured; one of our goals is to increase health awareness in everyday life’. As we observed, the exam process was usually accompanied by dialogue on how a woman may have gotten sick (e.g. partners, behaviours) and how to avoid getting sick in the future. Dr Z approached FSW as if they were friends or sisters when talking about their sexual relationships. The following passage describes a typical clinic scene based on our fieldwork observations:

FSW usually came either with another female friend, or their boyfriends (occasionally with pimps) in late morning and early afternoon before their business started. In a situation with boyfriends or pimps there (at clinic), the staff would avoid topics relating to commercial sex. In a safe environment, the dialogue usually happened in such a natural and friendly sisterhood way, that it dispelled women’s fear of seeing a doctor for STIs, and made the sex topics easier to talk about. They would also chat about the new changes of the sex industry, through which information would be collected on where new FSW were appearing, whether there was drug use in the venue, which venue was cracked down, etc. We also observed that calls came in quite often to consult for health issues, especially about pregnancy and abortion, or asking for help to refer to other hospitals if the service is out of the range of this clinic. (Field notes, end of 1st week, January 2012)

These supportive clinical services, which incorporated respect, concern and relationship building, were essential parts of JZ’s success in working with FSW and surpass the services that would typically be provided to a patient (FSW or otherwise) in a standard clinical setting. Supportive services were especially important for attracting FSWs who were hard to reach through traditional outreach work, such as street-standing FSWs and women who were very mobile. For example, many migrant FSWs now come to the centre to get tested before returning to their hometowns for holidays. As noted by one FSW:

I’ve known Dr Z for 4–5 years; she is a good and skilled person, we believe in her. – I have a child and husband at home and I’ll visit them soon – very exciting – I usually go home once or twice a year and definitely don’t want to transmit to my family some disease, you know, in this business, it is hard to tell – I don’t feel like I have a problem, but just to double check, to be safe and feel more comfortable. (FSW, in early 40s)

A welcoming clinic setting and high-quality clinical services were both essential elements of JZ’s success; neither component alone would be as successful at attracting and maintaining FSW’s engagement with the programme services.

Responsive outreach work with FSW

Outreach work consisted of on-site training to FSW about STI and HIV knowledge and strategies of how to avoid violence from clients and police, distribution of IEC materials, on-site health consultations and collection of blood for STI tests, visitation of incarcerated FSW and additional supportive activities. JZ’s regular outreach work happens at least three times a week. The outreach activities are conducted by pairs of workers (either one peer leader trained FSW and one CBO worker or two CBO workers if no peer leaders are available) and generally involve walking the neighbourhoods to visit sex work venues one by one. For remote areas, staff take a taxi or bus, or sometimes used their own cars. All staff and management participated in outreach work. This comprehensive participation familiarised staff with the local FSWs’ work situations – including venue organisation types – which in turn benefited their intervention work. Outreach services covered different types of sex work venues from streets to large karaoke bars. The sites and content of the outreach services vary depending on the occupational issues arising during the current time period, JZ’s relationship with the venues and the business situation of each site. As outreach coordinator Miss Chen described:

You can’t expect people to warmly welcome you every time, and you’d better prepare for that; after all, doing business and earning money is their first priority; and in some venues, especially those involved with drug use and ones you are not familiar with, the managers would be more cautious about what you talked about with the girls; and the girls also had some secrets that they don’t want to let other girls or the manager know – so most of the time, we actually just answered some questions about their health, or did some tests, drop the condoms and collect new information onsite, write it down. Then we go back to the clinic and try to get more detail when people come to our clinic or during some social activities – You also have to be flexible when doing outreach work. Once, during outreach, we learned that a FSW had just been robbed of her cell phone and wallet after providing services to a client, we changed our original plan, and instead discussed the theft issue in more detail, and we would put the information in the leaflets and share it with other FSW on how to protect their belongings when they go out with a client.

This flexibility and responsiveness in outreach work is a key example of how a structural approach differs from more traditional outreach approaches that focus more exclusively on HIV/STI-related concerns. Furthermore, the support JZ staff offered during these crisis events further strengthened their trust among FSWs, as described in greater detail below.

JZ programme staff also visited re-education centres where FSWs are detained for 6–24 months for engaging in sex work. Between 2008 and 2013, JZ staff visited 326 incarcerated FSWs. During fieldwork, the first author accompanied Dr Z to visit a middle-aged woman in a re-education centre who had been arrested twice. During the visit, Dr Z brought her new clothes and spent time comforting and encouraging her.

In addition, JZ provided a legitimate work setting for some FSWs who volunteer and serve as peer outreach workers. This was a particularly valued element for women who needed to keep their sex work hidden from children or family visitors. JZ also provided small-scale financial and medical aid for emergency cases, for example when women were robbed or when they needed financial assistance for STI treatment. Lastly, staff helped some FSWs to obtain identification cards and open their own bank accounts.

As noted earlier, the importance of responsive outreach work was particularly emphasised and improved after JZ’s progress evaluation in 2007, allowing JZ staff greater opportunities to learn about new needs of FSW and update staff knowledge of occupational health issues. From 2007, these interactions informed JZ’s continuous development of new IEC materials and provided topics to be discussed in more detail during FSW self-support group meetings and social activities. Standard outreach work in China follows a primarily didactic approach and is focused on delivering information or services that are believed to be important by the health providers. In comparison, the responsive outreach work provided by JZ reflected a two-way ‘conversation’ in that it was targeted for the local FSW to address occupational health issues collected from within the community. Taken together, these outreach activities provided social, psychological and material support to FSW that helped address structural risk factors including poverty, work status, stigma and access to services.

Create a supportive local environment

JZ staff worked to create a supportive local environment for sex workers through relationship building and social networking activities across four specific types of interpersonal relationships which are most closely linked to FSWs’ daily living and working situation: relationships within sex work, relationships with non-FSW neighbours, relationships and advocacy work with the local police and other stakeholders and relationships between JZ staff and FSW. In undertaking these activities, JZ also created an increasingly supportive local environment in which to continue their programmatic work, further supporting the success of the programme.

Development of mutual support within sex work

In China, sex work is a competitive business and FSWs lack the collective consciousness noted in other global settings (Zheng, 2009). These competitive framework and lack of collective consciousness alongside social stigma and anti-prostitution laws present significant obstacles for community building among FSWs. To address this problem, the JZ programme focused substantial efforts on improving relationships among FSWs, among managers and between FSWs and their managers.

Networking activities included inviting FSWs and managers to the JZ clinic for chatting, dining out for group dinners, having Karaoke and dance parties in entertainment venues and taking fieldtrips outside of the city for outdoor activities such as visiting local parks and mountains. As JZ’s programmatic work was limited in scale and frequency due to the intense time demands on the small staff, these activities outside of sex work venues provided opportunities for social networking among FSWs and worked as important ways to build collective consciousness (described below), which are rarely seen in other FSW intervention programmes in China. Relevant topics for women’s lives were regularly embedded in these activities including reproductive health concerns and strategies to maintain good business in sex work while keeping safe.

The social support and social networking activities facilitated by JZ also served an overarching goal of building critical consciousness among FSWs. Specific activities that helped build critical consciousness included JZ’s facilitation of the ‘photos of our life’ project to encourage women to photograph their daily lives and share with others and the self-support groups JZ formed among women. These small-scale self-support groups were initiated in each neighbourhood and led by key FSW peer educators. Peer educators recruited FSW participants across a range of different types of entertainment venue settings (e.g. street standers, salons, Internet, karaoke bar). These groups meet one to two times per month to share business information, discuss new issues emerging in their neighbourhoods and provide support for neighbourhood-related problems such as robbery and violence. Information and emergent issues discussed within these groups also served to inform the tailored IEC materials JZ created and distributed during outreach activities.

Improving relationship between FSW and non-SW neighbours

As noted by quite a few FSW, friendly (non-FSW) neighbours could help you watch your doors and let clients know you have a social support system, which would reduce the risk of violence and robbery. Conversely, poor relationships with neighbours often resulted in neighbours reporting illegal sex work activities to the police. The following passage presents an example of the feasibility of building a safer local environment for sex work through the initiatives of FSW (in this case, Miss Yang [pseudonym]):

When Dr Z brought me to Miss Yang’s small hair salon shop in the afternoon, she welcomed us in and we chatted about recent business, police crackdowns, etc. Yang is in her 40s with higher education than most other FSW. When Dr Z said she is very clever, willing to learn new things, and interested in sharing stories with others, Yang picked up the topic and gave us a few examples. ‘I always said, only those silly girls would be robbed or arrested; I worked here alone and am always cautious about safety; so I’ll purposely create a good relationship with my neighbours. You see the shop owners next door, when I first arrived, like others, they wouldn’t even look at me; but I didn’t care and didn’t give up, I went to their shops to buy things, and gave some fruits as gifts sometimes – with time, they changed …. When I go out with clients in cars, I would purposely say loudly to them ‘Brother X, I’m going out with a friend now’, and they would come out and respond – in this way, you actually told the client that you have some backup here and warn them not to do bad things; and my neighbour would also look at the car number – sometimes they even would check on me by phone to make sure I was safe.’ (Field notes, 16 January 2013)

While Miss Yang is an example of an FSW with better autonomy and capacity for relationship building, her experience was shared in JZ’s FSW group activities and promoted as one of the strategies women could use to build better neighbourhood relations. The JZ programme also strives to strengthen relationships with sex work venues and other small business shops in the neighbourhood in order to build community ties and provide opportunities to reduce stigma around FSW. These efforts often utilised creative, mutually beneficial strategies, such as contracting JZ’s newsletter to local print shops and dining at local restaurants.

Relationship building and advocacy work with the local police and other stakeholders

Dr Z has used her personal resources to build relationships with local authorities including policemen and officials in the health sector. These efforts include assisting with government projects on HIV/STI testing in order to gain support and sustainability for the JZ programme and periodically inviting key stakeholders (e.g. police, health officials) to dinner. As eating is one of the most important activities for socialising and building relationships in China, dinner opportunities were arranged to invite policemen. This helped build personal relationships to facilitate a better community environment and relationships with law enforcement. The team also creates opportunities to increase awareness and understanding of sex work, such as providing health lectures to local schools. Although official agreements to support JZ’s activities remain challenging due to the illegality of sex work, these efforts were forms of advocacy work and the strong personal relationships fostered by JZ helped improve some conditions for FSW including reduced violence from police during crackdowns and increased opportunities to visit incarcerated FSW.

Building trusting relationships between JZ programme staff and FSW

Trust is vital for working with at high-risk groups in China – such as FSW – who are socially stigmatised and conducting illegal work. Responses such as ‘I trust Dr Z’, and ‘We believed in her’ were frequently shared in discussions with FSW as they explained what motivated them to come to the JZ clinic, why they worked as peer educators and why they felt comfortable introducing other FSWs to the clinic.

JZ built trusting relationships through long-term efforts within the community doing outreach, providing clinic services and facilitating social activities. These relationships were tested and strengthened in situations where FSWs were in crisis. A typical case was recorded about Xue (pseudonym), an FSW who explained the process of how her hostile attitude changed to one of trust through interaction with the JZ programme. The following description is excerpted from research field notes:

Xue is in her early 30s with a young face. She had experienced many awful things in her life such as seeing a FSW friend being killed, being cheated by her boyfriend in whose bank account she saved all her money. Xue has known JZ programs for seven years, and is now an important program volunteer in addition to her own sex work business …. This is my third time to see Xue. We are sitting in her small but cosy place; only two of us, eating sunflower seeds and chatting.

Xue said she changed a lot since she met Dr Z:

I didn’t trust them at all at the first 1–2 years, I didn’t talk to them and even didn’t look at them when they came in trying to give me some material – I threw them away – I didn’t trust people, I usually put a knife under my pillow – and they (program staff) kept coming and trying to talk to me, and I went to the clinic several times when I didn’t feel good (STI) … With time, you know they are good people, so I began to participate in some activities, talked to aunt Z about my experience.

It was not only the attitude of the program staff that mattered, but more importantly, the mental and other support they provided. The program helped Xue open her own bank account to save money, and also persuaded her to visit her family who she had not seen since she left more than ten years ago. (Case record of Xue and field notes, 15th January 2013)

Tailored IEC material

The information JZ obtained and women generated through clinic services, outreach work and social networking and relationship-building activities informs JZ’s development of three types of tailored IEC materials: (1) contact cards with information about basic clinic services, location and programme phone numbers; (2) theme-based booklets targeting occupational health issues, such as reproductive health, HIV/STI, violence and drug use; and (3) monthly newsletters featuring local community issues, including stories and experiences written by FSW. These materials are available at the JZ main centre and delivered through outreach work. The contents of JZ’s IEC materials differ from China’s typical IEC materials where are primarily framed in a biomedical context and focused exclusively on condom use, HIV/STI information and testing. Of critical importance, FSWs are involved in the development process of JZ’s IEC materials – in content and form – as well as the distribution of the materials, greatly increasing the chances that they will actually be read by women.

Discussion

This paper provides an in-depth examination of the activities of a community-based FSW occupational health programme in China. Detailed description of the activities and elements of this programme is provided to illustrate how a structural approach can be developed and function for HIV prevention among FSWs in a setting like China.

Returning to the conceptual framework illustrated in Figure 1, the core elements of the structural approach adopted by the JZ programme primarily address the impacts of the social drivers of HIV/STI risk by providing individual-level services within an occupational health framework and by focusing on interpersonal and community-level relationships. The individual factors and occupational health issues JZ targeted at the individual level – such as violence, psychological and social support – address the needs generated by underlying social drivers such as anti-prostitution policy and social stigma (Choi & Holroyd, 2007; Huang, 2010; Yi et al., 2012) as well as the more traditional needs like HIV/STI knowledge, testing and care.

The JZ programme engages the structural approach of community mobilisation (Adimora & Auerbach, 2010) as it implements a series of social and community engagement activities that go beyond traditional condom delivery and STI testing and treatment, which constitute important strategies for mobilising the community. Even when using more traditional intervention methods – such as outreach work and IEC material development, the JZ programme embedded additional social elements to make these efforts more appropriate, welcoming, and tailored to the needs of the local community and FSWs.

The JZ programme’s interpersonal and community-level elements constitute the second point of the ‘structural approach’, which resulted in increased mutual support among sex workers, improved relationships between FSWs and their non-SW neighbours, better relationships with local police and government officials and trusting relationships between JZ programme staff and FSW. These are all critical elements of structural interventions implemented by the JZ FSW programme and found in the global literature (Biradavolu et al., 2009; Cornish & Ghosh, 2007; Swendeman et al., 2009). Taken as a whole, these activities aimed to strengthen FSW’s social support while simultaneously trying to shift the local environment for sex work in JZ City.

Our descriptive analysis of the JZ programme’s structural approach to HIV/STI risk reduction and occupational health promotion enriches the existing literature on structural health approaches by demonstrating the successes and challenges of this model within a specific occupational (sex work) and sociopolitical (China) context. Specifically, the sensitive legal and political context in China greatly limit the possibilities for community mobilisation and social movements of any kind, and community-based advocacy work against the illegal status of sex work is a particularly challenging issue. These contexts, in turn, limit the implementation of ‘structural approaches’ at the policy level and hinder community groups’ ability to build collective consciousness among FSWs, an approach which has gained success in other environments such as the FSW Sonagachi project in India (Swendeman et al., 2009). The JZ example presented in this paper illustrates how structural approaches can be practiced locally, efficiently and safely at a community level in spite of broader hostile political and social contexts.

The JZ FSW programme has limitations for scale up, such as the programme’s heavy reliance on institutionalised knowledge and relationships. Key personnel like Dr Z are uniquely dynamic leaders who have spent many years building up the necessary relationships and trust within the community to make the JZ programme possible. Nevertheless, the JZ programme case demonstrates the feasibility of structural-level interventions among FSWs even within an anti-prostitution and high-stigma setting such as China. Our findings support the importance and need to contextualise and tailor structural-level interventions much in the same way that individual-level interventions are tailoring their approaches and materials. In addition, future outcome evaluation is needed to formally evaluate the JZ model as an evidence-based approach prior to scale up.

Despite the challenges and diversity of China’s local contexts and opportunities for programme development, it may be feasible to apply successful elements of the JZ FSW programme to existing and future FSW intervention programmes. For government programmes, additional efforts could focus on working more closely with CBOs, combining occupational health issues in IEC material and trainings, recruiting female gynaecological and STI doctors like Dr Z into their teams and creating more welcoming STI testing and treatment settings. For CBO initiated programmes, efforts could focus on creating small self-support groups to protect against robbery and violence, providing psychological and social support for better mental health, facilitating a more supportive neighbourhood to reduce stigma and risks around sex work and referring FSW to good clinical services by mobilising various local and interpersonal resources. These intervention efforts within a structural approach will add to China’s HIV/STI achievements made at the health policy level (Wu, Sullivan, Wang, Rotheram-Borus, & Detels, 2007) and move towards more effective HIV prevention and health promotion among FSWs in China.

Acknowledgments

Funding

We acknowledge financial support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Research Funds of Renmin University of China [grant number 10XNJ059] and writing support from Partnership for Social Science Research on HIV/AIDS in China [grant number NICHD R24 HD056670]. We especially appreciate support from Oxfam Beijing office, staff and FSW peer educators from JZ FSW programme to assist the fieldwork.

Footnotes

The draft paper was presented in the 2nd International HIV Social Science and Humanities Conference, Paris, July 2013.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adimora AA, Auerbach JD. Structural interventions for HIV prevention in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(Suppl. 2):132–135. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbcb38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach J. Transforming social structures and environments to help in HIV prevention. Health Affairs. 2009;28:1655–1665. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach JD, Parkhurst JO, Cáceres CF. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: Conceptual and methodological. Global Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl. 3):293–309. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.594451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, Kerrigan D. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012;12:538–549. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biradavolu M, Burris S, George A, Jena A, Blankenship K. Can sex workers regulate police? Learning from an HIV prevention project for sex workers in southern India. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X-S, Peeling RW, Yin Y-P, Mabey DC. The epidemic of sexually transmitted infections in China: Implications for control and future perspectives. BMC Medicine. 2011;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China CDC. National intervention guidelines on female sex workers. Beijing: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Holroyd E. The influence of power, poverty and agency in the negotiation of condom use for female sex workers in mainland China. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2007;5:489–503. doi: 10.1080/13691050701220446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY. State control, female prostitution and HIV prevention in China. The China Quarterly. 2011;205:96–114. [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: How to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372:669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Smith M, Muessig K, Hallett T, Powers K, Kashuba A. Antiretroviral treatment of HIV-1 prevents transmission of HIV-1: Where do we go from here? Lancet. 2013;382:1515–1524. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61998-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish F, Ghosh R. The necessary contradictions of ‘community-led’ health promotion: A case study of HIV prevention in an Indian red light district. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.009. PMID: 17055635 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta G, Parkhurst J, Ogden J, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershatter G. Dangerous pleasure: Prostitution and modernity in twentieth-century Shanghai. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Li X. HIV/AIDS behavioral interventions in China: A literature review and recommendation for future research. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:603–613. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9483-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Poon AN, Zhang C. HIV/STI prevention interventions targeting FSWs in China: A systematic literature review. AIDS Care. 2011;23(Suppl. 1):54–65. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. Female sex workers in China: Their occupational concerns. In: Jing J, Heather W, editors. HIV in China. Sydney: UNSW Press; 2010. pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Henderson GE, Pan S, Cohen MS. HIV/AIDS risk among brothel based female sex workers in China: Assessing the terms, content and knowledge of sex work. Sexual Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:695–700. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000143107.06988.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Maman S, Pan S. Understanding the diversity of male clients of sex workers in China and the implications for HIV prevention programmes. Global Public Health. 2012;7:509–521. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2012.657663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Tao X, Liao M, Li J, Zhang N, Zhu X, Jia Y. An integrated individual, community, and structural intervention to reduce HIV/STI risks among female sex workers in China. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:717. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J. HIV, sex work, and civil society in China. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;204:S1218–S1222. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Zhang L, Gu Y, Feng L. Developing comprehensive HIV/AIDS intervention on female commercial sex workers by the platform of Health Pavilion. Soft Science of Health. 2008;22:309–311. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of People’s Republic of China; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; World Health Organization. 2011 estimates for the HIV/AIDS epidemic. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org.cn/pics/20130521161757.pdf.

- Pan S. Three red light district in south of China. Guangzhou: Qunyan Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rekart ML. Sex-work harm reduction. Lancet. 2005;366:2123–2134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67732-X. PMID: 16360791 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendeman D, Basu I, Das S, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus M. Empowering sex workers in India to reduce vulnerability to HIV and sexually transmitted diseases. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:1157–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Peng H, Wang K, Chang H, Zhang S, Yang L, Yang B. Female sex worker social networks and STI/HIV prevention in south China. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Ren X, Sapio F. Incarcerated sex workers and HIV prevention in China: Social suffering and social justice countermeasures. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang Q, Yin Y, Liang G, Jiang N, Gong X, Chen X. The effect of a structural intervention for syphilis control among 3597 female sex workers: A demonstration study in south China. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2012;206:907–914. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZY, Sullivan SG, Wang Y, Rotheram-Borus M, Detels R. Evolution of China’s response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 2007;369:679–690. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60315-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi H, Zheng T, Wan Y, Mantell JE, Park M, Csete J. Occupational safety and HIV risk among female sex workers in China: A mixed methods analysis of sex-work harms and mommies. Global Public Health. 2012;7:840–855. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2012.662991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng T. Red lights: The lives of sex workers in post-socialist China. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]