Abstract

Background/Objectives

While older adults comprise the most rapidly growing population segment, little is known about the provision of mental health care to older adults relative to younger adults.

Design

Analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.

Setting

Visits to office-based physicians, 2007-2010 (N=100,661).

Participants

Patient encounters with a mental health diagnosis or treatment, defined as visits: 1) resulting in mental disorder diagnosis; 2) including prescription or continuation of psychotropic medication; 3) to a psychiatrist; or 4) including psychotherapy.

Measurements

Visits were stratified by patient age (21-64y, ≥65y) and the percentage of each mental health care visit type among all office-based care was estimated by age group and converted to an annual rate per 100 population. Within each visit type, age groups were compared by clinical and demographic characteristics such as gender, diagnosed mental illness, and use of psychotropic agents.

Results

Relative to younger adults, older adults had a smaller proportion of visits with a mental disorder diagnosis (4.76% v. 9.53%, X2=228.21, p<.001), to a psychiatrist (0.94% v. 4.01%; X2=233.76, p<.001), and including psychotherapy (0.65% v. 2.30%; X2=57.65, p<.001). The percentage of older adult psychotropic visits was slightly smaller than among younger adults (18.06% v. 19.23%; X2=5.33, p=.02). Older adults had a higher rate of psychotropic visits (121.40 per 100 population) than adults (56.77).

Conclusions

Less care of older adults is from psychiatrists or incorporates psychotherapy. On a per-population basis, older adults have a far higher rate of psychotropic use compared to younger adults. Addressing the mental health care needs of older adults will require care in non-specialty settings.

Keywords: mental health, psychotropic, psychotherapy

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, the year after the first Baby Boomers turned 65 years old, the Institute of Medicine released its report The Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Adults: In Whose Hands?1 This report highlights the lack of providers with expertise necessary to address the mental health needs of older adults, especially given the burden of mental disorders in this rapidly expanding group.2,3 Efforts to meet the challenge of delivering mental health care to older adults should arise from knowledge about the nature and extent of care they currently receive. Care of mental disorders in children relative to the adult population, for example, has received a significant amount of coverage in both the academic and lay press, frequently highlighting the shortage of specialty mental health providers and increased use of psychotropic medication.4-7 With few exceptions,8-10 however, prior analyses of mental health care using nationally-representative data rarely study older adults separately from the general adult population.

Yet for a variety of reasons, delivery of mental health care to older adults merits additional attention. Due to accumulation of medical comorbidity11 as patients age as well as changes in drug metabolism,12,13 pharmacotherapy of mental disorders can be complicated by potential drug-disease or drug-drug interactions that are less likely in younger adults. The current version of the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria lists nearly every psychotropic medication as potentially inappropriate.14 Older adults may have different treatment preferences than younger adults15 and are less likely to receive treatment in specialty mental health settings. ENREF 158,10 Use of psychotherapy may be perceived to be limited as the burden of cognitive impairment increases with age, though evidence suggests psychotherapy is feasible and possibly beneficial even for patients with dementia.16,17 ENREF 15 In addition, while most older adults ultimately gain insurance coverage through Medicare, psychiatrists are less likely than other providers to accept Medicare,18 while older patients may have limited income and thus be unable or unwilling to pay out of pocket, creating an additional potential barrier to receiving specialty care.

For purposes of both providing patient care and training providers, it is important to investigate whether the current understanding of outpatient mental health treatment applies to older adults. With just 1,700 geriatric psychiatrists in practice at this time,19 ENREF 27 access to specialty care will be the exception rather than the norm as the older adult population continues to grow. Refining knowledge regarding where older adults with mental disorders are seen and the nature of the mental health care they receive is critical to understanding quality and improving delivery. We aim to describe and possibly differentiate the outpatient mental health care of younger and older adults by building upon the recent work of Olfson et al.20 We will examine four broad categories of care: outpatient visits with a mental health diagnosis; visits utilizing psychotropic medication; visits to a psychiatrist; and visits including psychotherapy. We will describe what proportion of ambulatory care nationwide is dedicated to these types of visits, whether these visit types differ between age groups, and what demographic and other clinical characteristics are associated with mental health care.

METHODS

Source of the Data

Data for these analyses were obtained from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). The NAMCS, administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS; Hyattsville, MD) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a national survey designed to “provide objective, reliable information about the provision and use of ambulatory medical care services in the United States.” This study utilizes data from the 2007-2010 survey years, the most recent available.

Survey Design

NAMCS is a national probability sample survey of office-based and community health center-based physicians that yielded a total of 125,029 patient encounters across the four study years. Physicians are sampled from the master files maintained by the American Medical Association and American Osteopathic Association; physicians in the specialties of anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology are excluded. In addition, encounters such as house calls or those to institutional settings (e.g., nursing homes) are not included. Each physician is assigned to a 1-week reporting period, during which time a log is maintained by office staff of all patient visits during the reporting period. At the end of the week, visits are randomly selected from this list using a random start and predetermined sampling interval. Data for selected visits are recorded by the physician or office staff on a standardized, one-page form. The overall physician response rate over the four years ranged from 58.3% to 62.1%. Adjusting for key survey design elements allows analyses to represent total annual visits to US office-based physicians.21

Mental Health Care Visit Classification

To explore how the burden of mental disorders and rates of mental health treatment in outpatient care vary by age, we considered four types of visits following Olfson et al.’s recent analyses20: 1) those resulting in a mental disorder diagnosis; 2) those where psychotropic medication was prescribed; 3) visits to a psychiatrist; and 4) visits where psychotherapy was provided. Going forward, “mental health care visit” will refer to these four visit types considered together. For the purposes of these analyses, a “mental health care visit” does not refer exclusively to a visit in specialty mental health care.

As part of the information collected at each NAMCS encounter, up to three diagnoses are recorded using the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition). For these analyses, encounters were then classified as to the presence or absence of a given condition.22,23 For example, visit diagnosis codes of 296.2x-296.3x, 296.82, 298.0x, 300.4x, 309.1x, or 311.x defined encounters for a depressive disorder. Similar criteria were applied to define visits for psychotic disorders (295.x, 297.x, 298.1x-298.9x, and 299.1x), bipolar disorder (296.0x-296.1x, 296.4x-296.81, 296.89, and 301.13), anxiety disorders (300.0x, 300.2x, 300.3x, 309.21, 309.81, and 313.0x), substance-related disorders (291.x-292.x, 303.x-305.x), and dementia (290.1-290.4, 294.1, 331.0, 331.1, 331.2, and 331.82). Lastly, a category was created for encounters with any psychiatric diagnosis, including dementia (290-319, 331.0, 331.1, 331.2, and 331.82).

Survey data includes up to 8 medications that are prescribed, ordered, supplied, administered, or continued during each visit. For these analyses, a visit was classified as a psychotropic visit if any of the following classes of medications (Appendix: Table 1) was included in the visit medication list: antidepressants, anxiolytics/sedatives/hypnotics (including benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine sedatives), antipsychotics, mood stabilizers (including lithium, carbamazepine, valproate and derivatives, lamotrigine), or stimulants (including atomoxetine). A given visit could include medications from multiple classes.

Appendix: Table 1.

Psychotropic drugs reported in the 2007-2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

| Antidepressants | Anxiolytics | Antipsychotics | Mood Stabilizers |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Amitriptyline | Alprazolam | Chlorpromazine | Carbamazepine |

| Amoxapine | Buspirone | Fluphenazine | Lamotrigine |

| Bupropion | Butabarbital | Haloperidol | Lithium |

| Citalopram | Butalbital | Loxapine | Valproate/divalproex |

| Clomipramine | Chloral hydrate | Molindone | |

| Doxepin | Chlordiazepoxide | Perphenazine | |

| Duloxetine | Clonazepam | Pimozide | |

| Escitalopram | Clorazepate | Prochlorperazine | |

| Fluoxetine | Diazepam | Thioridazine | |

| Fluvoxamine | Diphenhydramine | Thiothixene | |

| Imipramine | Doxepin | Trifluoperazine | |

| Maprotiline | Doxylamine | ||

|

|

|||

| Mirtazapine | Estazolam | Second Generation: | Stimulants |

|

|

|||

| Nefazodone | Eszopiclone | Aripiprazole | Methylphenidate |

| Nortriptyline | Flurazepam | Clozapine | Dexmethylphenidate |

| Paroxetine | Hydroxyzine | Olanzapine | Amphetamine |

| Phenelzine | Lorazepam | Paliperidone | Dextroamphetamine |

| Protriptyline | Meprobamate | Quetiapine | Pemoline |

| Selegiline | Midazolam | Risperidone | Atomexitine |

| Sertraline | Oxazepam | Ziprasidone | |

| Tranylcypromine | Pentobarbital | ||

| Trazodone | Phenobarbital | ||

| Venlafaxine | Prazepam | ||

| Pyrilamine | |||

| Ramelteon | |||

| Temazepam | |||

| Triazolam | |||

| Tybamate | |||

| Zaleplon | |||

| Zolpidem | |||

NAMCS classifies providers into fifteen specialty groups, which for these analyses were grouped into three categories: psychiatrist, primary care provider (pediatrics, family medicine, internal medicine), or other medical specialty. The survey elicits information regarding the type of services and procedures performed during the office encounter, including a specific item (yes/no) regarding provision of psychotherapy.

After determining which surveyed visits belonged to each of the mental health visit categories, the visits were then stratified by patient age into two categories: adult (21-64y) and older adult (≥65y). The visit categories were not mutually exclusive. For example, a visit to a general internist for a 55y patient with diagnoses of diabetes and major depressive disorder who received psychotherapy and was prescribed sertraline would be included in three of the four mental health care visit categories (all except psychiatrist visit) for the adult group.

Other Characteristics

Sociodemographic items from the survey utilized for these analyses included: gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, other), payer (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, other; categories not mutually exclusive), urban or rural office location (as determined by Metropolitan Statistical Area status), and region of the country (Northeast, South, Central, West).

Statistical Methods

For each of the four mental health care visit types, we determined annual estimates of office-based visits, summed the estimates for each type across the four study years (2007-2010), and then stratified by patient age (younger and older adult). Analyses were adjusted for visit weight, clustering within physician practice, and stratification using survey design elements provided by NCHS to generate national visit estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.21 Survey years were combined as recommended by NCHS in order to produce a more reliable annual visit rate estimate.22 To generate population-based visit rates for the four visit types, the denominator (i.e., US population for age group) was obtained from US Census population estimates for the four-year study interval to derive an annual visit rate per 100 population for each age group.23 Population-based visit rates were also determined for individual psychotropic class.

After determining the population-based visit rates, subsequent analyses compared how clinical and demographic characteristics varied by age group for each type of mental health care visit. Categorical variables (e.g., gender) were examined by comparing the proportion of visits in each age group that corresponded to a given category (e.g., 32.31% of older adult visits resulting in a mental disorder diagnoses were by males, compared to 38.76% of adult visits). Chi-squared tests were performed to determine associations between demographic and clinical characteristics and the four visit types for each age group, with results weighted to allow national inferences. Analyses were conducted in Stata 13.1 (College Station, TX) using two-sided analyses with α = .05. For population-based visit rates, which combine NAMCS survey data (numerator) with US Census information (denominator), statistical significance was approximated by non-overlap of 95% confidence intervals.24

RESULTS

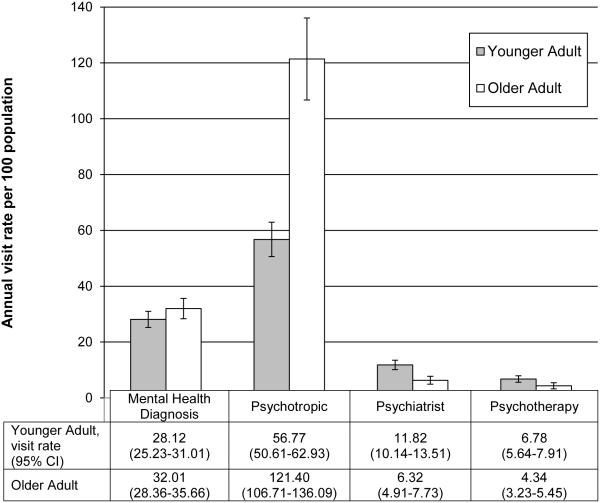

Over the four survey years, there were a total of 125,029 office visits. When limited to younger and older adults, there were 100,661 visits. Table 1 presents the proportion of total outpatient visits for each age group in each of the four mental health care visit categories. Relative to the office-based care provided to younger adults, mental health care visits comprised a smaller proportion of the care of older adults. Of the visit types, the proportion of psychotropic visits between age groups was most similar, though slightly lower for older adults (18.06% [16.94-19.24%] v. 19.23% [95% CI 18.32-20.18%], X2=5.33, p=.02). The annual population-based visit rates for each type of mental health visit by age group are presented in Figure 1. The annual psychotropic visit rate for older adults was 121.40 (CI 106.71-136.09), much higher than the adult rate of 56.77 (CI 50.61-62.93). Older adults had lower rates of both psychiatrist and psychotherapy visits.

Table 1.

Mental health care visits as a percentage of total office-based physician visits for younger adults and older adults in the U.S. from 2007-2010

| Visit Type | Younger Adult (21-64y) (n=67,653) |

Older Adult (≥65y) (n=33,008) |

X2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total office-based visits,

in millions |

2110.28 | 1052.84 | ||

| Mental health visit | ||||

| Mental Disorder Diagnosis, %, (95% CI) |

9.53 (8.92-10.2) |

4.76 (4.35-5.21) |

228.21 | <.001 |

| Psychotropic Medication | 19.23 (18.32-20.18) |

18.06 (16.94-19.24) |

5.33 | .02 |

| Visit to Psychiatrist | 4.01 (3.53-4.54) |

0.94 (.75-1.18) |

233.76 | <.001 |

| Psychotherapy | 2.30 (1.94-2.72) |

0.65 (.49-.84) |

57.65 | <.001 |

CI: confidence interval

Figure 1.

Annual population-based rates and 95% confidence intervals by age group for visits with a mental disorder diagnosis, psychotropic medication, to a psychiatrist, or psychotherapy.

Mental Disorder Visits

Compared to younger adults (Table 2), older adult females were more likely to have a visit with a mental disorder diagnosis (67.69% v. 61.24%; X2=12.86, p<.001), while the proportion of these visits between age groups did not vary by race/ethnicity. There was no variation by geographic area or metropolitan status.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of office-based mental health care visits for adults and older adults in the U.S. from 2007-2010

| Mental Disorder Diagnosis (n=9,286) |

Psychotropic (n=20,043) |

Psychiatrist (n=4,491) |

Psychotherapy (n=2,763) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| 21-64y | ≥65y | X2 | 21-64y | ≥65y | X2 | 21-64y | ≥65y | X2 | 21-64y | ≥65y | X2 | |

| Age, mean (SE), y | 44.13 | 76.40 | n/a | 46.77 | 75.88 | n/a | 44.32 | 72.34 | n/a | 44.44 | 73.31 | |

| (.25) | (.33) | (.19) | (.15) | (.31) | (.48) | (.47) | (.60) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male, %d | 38.76 | 32.31 | 12.86c | 33.53 | 34.41 | 0.98 | 39.89 | 32.18 | 4.67a | 40.04 | 34.38 | 1.96 |

| Female | 61.24 | 67.69 | 66.47 | 65.59 | 60.11 | 67.82 | 59.96 | 65.62 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 81.08 | 81.88 | 0.29 | 80.40 | 83.02 | 0.29 | 81.05 | 84.57 | 0.71 | 83.17 | 89.37 | 4.18a |

| Non-Hispanic black | 8.01 | 7.15 | 0.49 | 8.86 | 6.66 | 10.65b | 8.78 | 3.26 | 12.38c | 7.02 | 3.55 | 3.62 |

| Hispanic | 7.57 | 7.85 | 0.07 | 7.60 | 7.69 | 0.03 | 6.78 | 9.15 | 0.72 | 5.75 | 4.38 | 0.48 |

| Other | 3.34 | 3.13 | 0.13 | 3.15 | 2.62 | 1.50 | 3.39 | 3.02 | 0.10 | 4.06 | 2.70 | 0.98 |

| Provider Specialty | ||||||||||||

| Primary care | 49.33 | 63.59 | 16.32c | 49.82 | 52.85 | 2.47 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 9.63 | 20.26 | 4.42a |

| Other specialty | 11.56 | 18.41 | 13.60c | 34.10 | 43.27 | 24.12c | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2.75 | 3.56 | 0.18 |

| Psychiatrist | 40.10 | 19.42 | 81.33c | 17.11 | 4.35 | 175.13c | n/a | n/a | n/a | 87.92 | 80.16 | 5.43a |

| MH diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Any MH diagnosis | n/a | n/a | n/a | 36.82 | 19.27 | 191.16c | 95.37 | 93.19 | 1.10 | 94.16 | 89.14 | 5.08a |

| Depression | 42.73 | 38.35 | 5.92a | 17.52 | 8.12 | 159.59c | 44.08 | 52.58 | 7.33b | 44.79 | 54.23 | 4.03a |

| Bipolar disorder | 11.44 | 3.87 | 59.46c | 4.97 | 0.83 | 137.91c | 19.16 | 12.75 | 6.36a | 16.82 | 12.54 | 2.07 |

| Psychotic disorder | 5.22 | 3.27 | 7.37b | 2.15 | 0.67 | 41.78c | 9.62 | 9.26 | 0.05 | 6.57 | 7.04 | 0.07 |

| Substance use disorder |

11.37 | 5.79 | 31.15c | 2.76 | 0.51 | 54.34c | 7.01 | 1.70 | 10.24b | 8.23 | 2.31 | 6.79b |

| Anxiety disorder | 29.00 | 21.70 | 12.91c | 11.75 | 4.34 | 98.67c | 27.08 | 20.91 | 4.19a | 28.06 | 18.18 | 10.49b |

| Dementia | 0.16 | 9.76 | 598.01c | <0.01 | 2.01 | 293.13c | <0.01 | 5.36 | 415.52c | <0.01 | 1.05 | 42.62c |

|

Psychotropic

medication |

||||||||||||

| Any | 74.34 | 73.09 | 0.36 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 82.17 | 83.58 | 79.55 | 80.96 | 16.01 | 0.06 |

| Antidepressant | 53.62 | 42.22 | 33.21c | 64.03 | 51.94 | 122.56c | 61.92 | 62.02 | 61.93 | 61.74 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Anxiolytic | 36.37 | 31.06 | 6.08a | 50.26 | 50.80 | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 38.30 | 41.78 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| Mood stabilizer | 9.14 | 3.41 | 33.54c | 8.00 | 0.03 | 117.25c | 16.56 | 8.73 | 14.16 | 8.71 | 5.77a | 5.93a |

| Antipsychotic | 16.07 | 11.06 | 13.75c | 12.13 | 6.37 | 59.19c | 29.48 | 28.93 | 24.02 | 24.56 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Stimulant | 3.75 | 0.81 | 31.11c | 2.63 | 0.37 | 101.71c | 5.86 | 2.86 | 5.15 | 2.98 | 2.50 | 2.57 |

|

Psychotherapy

visit |

22.70 | 12.08 | 43.89c | 9.50 | 2.89 | 135.93c | 50.41 | 55.01 | 1.24 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Payment form | ||||||||||||

| Medicare | 10.86 | 77.45 | 1084.40c | 11.86 | 80.63 | 2540.21c | 14.13 | 64.12 | 247.30c | 10.12 | 65.03 | 287.02c |

| Medicaid | 15.99 | 6.55 | 40.6500c | 13.41 | 6.01 | 66.53c | 17.61 | 10.98 | 3.72 | 13.33 | 6.15 | 6.64a |

| Private | 58.80 | 46.53 | 21.61c | 66.63 | 49.13 | 109.06c | 48.07 | 33.95 | 12.28c | 49.40 | 37.28 | 5.22a |

| Other | 19.48 | 5.84 | 142.91c | 13.89 | 3.76 | 141.35c | 27.43 | 17.54 | 9.51b | 31.62 | 18.83 | 10.88b |

| Geographic region | ||||||||||||

| Northeast | 21.55 | 20.02 | 0.93 | 18.79 | 17.07 | 2.80 | 29.28 | 38.78 | 4.21a | 33.82 | 39.92 | 1.78 |

| Midwest | 22.42 | 22.16 | 0.02 | 23.06 | 21.92 | 0.95 | 15.81 | 13.04 | 1.00 | 17.94 | 17.86 | 0.00 |

| South | 34.83 | 37.75 | 1.47 | 37.97 | 41.05 | 3.23 | 33.55 | 28.85 | 0.95 | 21.82 | 17.61 | 1.16 |

| West | 21.19 | 20.06 | 0.43 | 20.18 | 19.96 | 0.02 | 21.36 | 19.33 | 0.32 | 26.41 | 24.61 | 0.13 |

| Metropolitan area | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 86.82 | 85.85 | 0.40 | 87.47 | 86.63 | 0.36 | 89.24 | 85.42 | 1.85 | 90.83 | 85.71 | 3.01 |

| No | 12.32 | 13.14 | 12.53 | 13.37 | 10.76 | 14.58 | 9.17 | 14.29 | ||||

p< .05,

p< .01,

p< .001

all values are percentages except age

A larger proportion of mental disorder visits for older adults were to primary care and other specialty providers, while 19.42% of these visits were to psychiatrist for older adults, compared to 40.10% for adults (X2=81.33, p<.001). Older adults had a larger proportion of visits with a dementia diagnosis, while other diagnoses accounted for a smaller share of visits than for younger adults. Among mental disorder visits, nearly 75% of patients received psychotropic medication, which did not vary by age group.

Psychotropic Visits

Among visits where a psychotropic medication was prescribed, the gender distribution did not differ between age groups. Older adult non-Hispanic black patients accounted for a smaller share of psychotropic visits than their younger adult counterparts did (6.66% v. 8.66%; X2=10.65, p=.0011). Otherwise, psychotropic visits did not vary across age groups by race/ethnicity or geography.

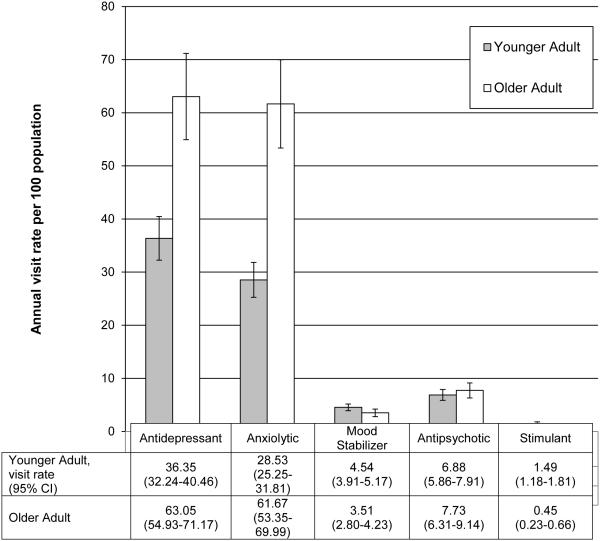

Among older adult visits with a psychotropic medication prescribed, just 4.35% of visits were to a psychiatrist, compared to 17.11% for younger adults (X2=175.13, p<.001). The presence of a mental health diagnosis among psychotropic visits was relatively low for both age groups, though lower for older adults (19.27% v. 36.82%, X2=191.16, p<.001). Among psychotropic visits, depression and anxiety were the most common diagnoses for both age groups. For both age groups, about half of the psychotropic visits involved anxiolytics (50.26% for younger adult, 50.80% for older adult; X2=.22, p=.64). Figure 2 presents medication visits on a per capita basis by medication type. Older adults had nearly double the rates of both antidepressant and anxiolytic visits, with similar rates of mood stabilizer and antipsychotic use relative to younger adults.

Figure 2.

Annual population-based visit rates and 95% confidence intervals by age group for psychotropic visits by medication class.

Visits to Psychiatrists

Among older adult patients, women accounted for 67.82% of psychiatrist visits, an even larger percentage than among younger adults (60.11%; X2=4.67, p=.03), while older adult non-Hispanic black patients accounted for fewer visits than their younger counterparts (3.26% v. 8.78%; X2=12.38, p<.001). Psychiatrist visits were the only type of mental health visit to demonstrate a difference by geographic region: a larger percentage occurred in the Northeast for older adult patients than younger (38.78% v. 29.28; X2=4.21, p=.04).

Older adult patients seeing a psychiatrist were more likely to have depression and dementia than younger patients, while they were less likely to have bipolar, substance use, or anxiety disorders than younger counterparts.

Psychotherapy Visits

The gender balance of psychotherapy visits did not differ in a statistically significant fashion between age groups. Non-Hispanic white patients accounted for an even larger percentage of psychotherapy among older adults than they did among younger adults (89.37% v. 83.17%; X2=4.18, p=.04).

For older adults, primary care providers provided 20.26% of the psychotherapy visits, double the 9.63% of such visits to younger adults (X2=4.42, p=.03). The majority of older adult psychotherapy visits were for a depression diagnosis (54.25% v. 44.79% for younger adults; X2=4.03, p=.04), with a smaller share of visits than for younger adults for substance use or anxiety disorders.

DISCUSSION

Prior work has described psychotropic use and psychotherapy in general practice and specialty psychiatric settings, though these analyses generally consider the adult population overall or youth relative to adults.25-28 A recent, broad overview of office-based mental health treatment considered children, adolescents, and adults; again, treatment of older adults was not considered separately.20 Treatment of older adults with mental disorders merits additional specific attention, as they often have more comorbid medical problems, are sensitive to psychotropic medication side effects, have greater potential for polypharmacy-related adverse events, and will be the fastest growing segment of the population over the coming decades.11,29-32 These specific treatment-related concerns can only be addressed when paired with knowledge regarding where and what manner of treatment currently occurs.

To our knowledge, these are the first analyses to broadly consider if and how the provision of outpatient mental health care varies between younger and older adults, as both a proportion of all care provided and on a per capita basis. Visits resulting in a mental disorder diagnosis account for 4.76% of all older adult office-based visits, about half the 9.53% for younger adults. On a per capita basis, the number of visits with a mental disorder diagnosis is equivalent between the two age groups. However, the rate of psychiatrist and psychotherapy visits for older adults is lower, while psychotropic use is far higher. This older adult psychotropic visit rate of 121.40 is nearly double the 65.90 generated by Olfson et al. for the general adult population in their recent analyses of the same data source.20 The high rate of anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic visits is particularly concerning in light of recent evidence associating benzodiazepine use with development of dementia.33,34

This work highlights the large role of non-psychiatrist providers in the provision of mental health care in general and for older adults in particular. Our findings suggest that defining mental health care as encounters with a psychiatrist or other mental health professional does not accurately reflect where patients with mental disorder diagnoses are seen and receive pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy. Less than one percent of all ambulatory physician encounters for older adults are to psychiatrists, and psychiatrists account for just 4.35% of visits including psychotropic use by older adults. Interestingly, primary care providers account for 20.26% of older adults’ psychotherapy visits in comparison to just 9.63% of such visits for younger adults. It is encouraging that primary care providers are employing psychotherapy, though this may suggest a lack of access to psychiatrists due to either provider shortage or psychiatrists’ significantly lower rate of accepting Medicare.18 Unfortunately, the survey does not provide information about the nature of psychotherapy provided.

Considering the clinical and demographic characteristics of four visit categories, several trends emerge. First, the gender imbalance for older adults with mental disorder diagnoses and treatment is generally consistent with, if not worse than, that found in the younger adult population. Older adults females comprised a larger share of visits with a mental disorder diagnosis and to a psychiatrist than among younger adults. While men do have a shorter life expectancy, longevity differences alone cannot account for the gender gap in mental health diagnoses and treatments in older adults. Older adult non-Hispanic black patients accounted for a smaller share of psychotropic visits and visits to psychiatrists than younger counterparts, while older adult non-Hispanic white patients accounted for more psychotherapy visits. However, the rate of visits with mental disorder diagnoses between age groups did not vary by race/ethnicity. The lower use of psychotropic medication may reflect treatment preferences among non-Hispanic black patients.35 However, the finding that older non-white groups did not account for more psychotherapy visits than their younger counterparts possibly suggests difficulty accessing this type of treatment.

Our work has several limitations. Since NAMCS is a nationally representative survey of outpatient visits, patient-level clinical assessments are not available. It may be that the high rate of psychotropic prescribing for older adults is clinically appropriate while the lower rates for adults and youth represent under-treatment, though without clinical assessments such conclusions cannot be made. Visit diagnoses are limited to three, which means that mental disorders may be underreported (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder is item 4 on the problem list and is left off the survey instrument). This underreporting would be more likely for older adults as they have more medical conditions relative to adults or youth,11 so the visit estimate for mental disorders in older adults in particular is likely an underestimate. In addition, it is possible that some portion of the psychotropic medication use is for a non-psychiatric indication such as pain or insomnia. However, given the lack of clinical assessment for these patients and the limited list of diagnoses, it is difficult to make inferences about potentially off-label use with this data source.

For the first time, these findings present data that allow direct comparison for older adults relative to younger adults for office-based mental health visits nationally. As such, the findings suggest that patterns of care for older adults are quite distinct from the younger adult population. While visits with a mental disorder diagnosis for older adults account for about one half the proportion of such visits for younger adults, psychotropic use is similar, while psychiatrist and psychotherapy visits account for a much smaller share of total outpatient care. When converted to a per-population basis, the psychotropic visit rate is far higher for older adults, demonstrating the extent to which these medications permeate outpatient office-based care.

Given the financial and time constraints on clinical care and training, these analyses provide data that health systems can use as they shepherd resources in the manner that best-serves patient need. The workforce issues in psychiatry are longstanding, and these findings demonstrate the extremely limited role that psychiatrists play in the delivery of mental health care to older adults. In addition, this work highlights the pervasiveness of psychotropic use in the outpatient care of older adults, heightening concern about the potential appropriateness of use.8,9,36 There is tremendous need to develop and implement systems of care that can serve patients both where they are and where they wish to be seen;15,37 for older adults, this means outside of specialty mental health care. Hopefully new Medicare-led initiatives in bundled payment and population-based care will make implementation of models such as collaborative care more financially viable.38,39 Regardless, it is critical that non-psychiatric providers receive more training in and support for the management of mental disorders in their clinical practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding Source: This work was supported by the Beeson Career Development Award Program (NIA K08AG048321, AFAR, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and The Atlantic Philanthropies).

Sponsor’s Role: none.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: the authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions: DTM acquired and analyzed the data and prepared the first draft of this manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript, helped interpret the results, and guided additional study questions.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . The mental health and substance use workforce for older adults: In whose hands? National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartels SJ, Naslund JA. The underside of the silver tsunami--older adults and mental health care. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:493–4963. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1211456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeste DV, Alexopoulos GS, Bartels SJ, et al. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: Research agenda for the next 2 decades. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:848–853. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crystal S, Olfson M, Huang C, et al. Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: Safety, effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Affairs. 2009;28:w770–781. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996-2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarz A. Attention disorder or not, children prescribed pills to help in school. The New York Times. 2012 http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/09/health/attention-disorder-or-not-children-prescribed-pills-to-help-in-school.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed March 8, 2014.

- 7.Schwarz A. Doctors train to spot signs of A.D.H.D. in children. The New York Times. 2014 http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/19/health/doctors-train-to-evaluate-anxiety-cases-in-children.html. Accessed March 8, 2014.

- 8.Maust DT, Oslin DW, Marcus SC. Effect of age on the profile of psychotropic users: Results from the 2010 national ambulatory medical care survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:358–364. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiechers IR, Kirwin PD, Rosenheck RA. Increased risk among older veterans of prescribing psychotropic medication in the absence of psychiatric diagnoses. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:531–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klap R, Unroe KT, Unutzer J. Caring for mental illness in the united states: A focus on older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman C, Rice D, Sung H-Y. Persons with chronic conditions. JAMA. 1996;276:1473–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotrich FE, Pollock BG. Aging and clinical pharmacology: Implications for antidepressants. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:1106–1122. doi: 10.1177/0091270005280297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollock BG. The pharmacokinetic imperative in late-life depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:S19–23. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000162809.69323.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American geriatrics society updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gum AM, Areán PA, Hunkeler E, et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist. 2006;46:14–22. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanley MA, Calleo J, Bush AL, et al. The peaceful mind program: a pilot test of a cognitive–behavioral therapy–based intervention for anxious patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:696–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheston R, Jones K, Gilliard J. Group psychotherapy and people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 2003;7:452–461. doi: 10.1080/136078603100015947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, et al. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:176–181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Geriatrics Society How many board certified geriatricians and geropsychiatrists are there in the US? http://www.americangeriatrics.org/advocacy_public_policy/gwps/gwps_faqs/id:3183. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- 20.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, et al. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:81–90. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 NAMCS Micro-data file documentation. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NAMCS/doc2010. Accessed December 12, 2013.

- 22.Hsiao C-J, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Understanding and using NAMCS and NHAMCS data: data tools and basic programming techniques. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/nchs2010/03_Hsiao.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2013.

- 23.United States Census Bureau, US Department of Commerce Population estimates: population and housing unit estimates. http://www.census.gov/popest/index.html. Accessed December 28, 2013.

- 24.Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Confidence intervals rather than p values: Estimation rather than hypothesis testing. BMJ. 1986;292:746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6522.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:848–856. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National trends in outpatient psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1456–1463. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcus SC, Olfson M. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in psychotropic medication polypharmacy in office-based psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:26–36. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kane JM, Woerner M, Lieberman J. Tardive dyskinesia: Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8:52S–56S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeste DV, Rockwell E, Harris MJ, et al. Conventional vs. Newer antipsychotics in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;7:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Harrold LR, et al. Risk factors for adverse drug events among older adults in the ambulatory setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1349–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howden LM, Meyer JA, United States Census Bureau, US Department of Commerce Age and Sex Composition: 2010. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2013.

- 33.Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: Prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Billioti de Gage S, Moride Y, Ducruet T, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of alzheimer’s disease: Case-control study. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among african-american, hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care. 2003;41:479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mojtabai R. Diagnosing depression in older adults in primary care. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1180–1182. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1311047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Coakley EH, Cheal K, et al. Satisfaction with mental health services in older primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:371–379. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000196632.65375.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maust DT, Oslin DW, Marcus SC. Mental health care in the accountable care organization. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:908–910. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katon WJ, Unutzer J. Health reform and the affordable care act: The importance of mental health treatment to achieving the triple aim. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:533–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]