Abstract

Theory and research point to the role of attachment difficulties in borderline personality disorder (BPD). Attachment insecurity is believed to lead to chronic problems in social relationships, due, in part, to impairments in social cognition, which comprise maladaptive mental representations of self, others, and self in relation to others. However, few studies have attempted to identify social cognitive mechanisms that link attachment insecurity to BPD and to assess whether such mechanisms are specific to the disorder. For the present study, empirically derived indices of mentalization, self-other boundaries, and identity diffusion were tested as mediators between attachment style and personality disorder symptoms. In a cross-sectional structural equation model, mentalization and self-other boundaries mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and BPD. Mentalization partially mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and antisocial personality disorder (PD) symptoms, and self-other boundaries mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and avoidant PD symptoms. The findings support theories that insecure attachment is associated with difficulties in social cognition and that a distinctive pattern of impairment characterizes BPD.

Keywords: Attachment, identity-diffusion, self-other disturbance, mentalization, self-other differentiation, borderline personality pathology

Researchers and theorists frequently employ attachment theory to explain interpersonal and social cognitive problems in BPD (e.g., Bateman & Fonagy, 2004; Meyer & Pilkonis, 2005). A central aspect of attachment theory is the idea that attainment of the goal of attachment, “felt security” (Sroufe & Waters, 1977), allows an individual to enter a generative cognitive mode characterized by clear thinking and creativity. This state allows cognitive space for thinking unrelated to attachment needs. Rather than worries about threat or one's ability to cope, felt security signals the ability to engage in high level thinking and social cognition (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Attachment security results when an individual experiences his/her attachment needs as being met routinely, which promotes the development of working models of the self as lovable and others viewed as dependable, helpful and supportive (Bowlby, 1982). Theorists, thus, argue that secure attachment is important to both social cognitive and identity development (Bateman & Fonagy, 2004). Each of these domains is impaired in BPD (Akhtar, 1984; Dziobek et al., 2011). Such impairments are expected from individuals with habitually hyperactive attachment systems, among whom felt security is rarely attained. Researchers have consistently linked attachment problems and BPD (e.g., Melges & Swartz, 1989). However, limited research exists regarding the mechanisms that account for this link. In addition, few studies have addressed whether attachment disturbance and social cognitive disturbances are specific to BPD, or whether they characterize personality disorders (PDs), such as Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) or Avoidant Personality Disorder (AVPD), more generally.

Attachment, Social Cognition, and BPD

Numerous studies demonstrate attachment anxiety and BPD are related (for review, see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). BPD symptoms map closely on to core features of extreme attachment anxiety: affective lability, unstable relationships, feelings of emptiness and loneliness, chronic abandonment fears and identity diffusion (Meyer & Pilkonis, 2005). Avoidant attachment has been less consistently associated with personality disorders generally (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007), and is not considered a primary risk factor for BPD. Research has also established a relationship between attachment insecurity and other personality disorders. Conceptually similar to BPD, AVPD has a dynamic of an individual wanting closeness and fearing rejection (Bartholomew, Kwong, & Hart, 2001), suggesting presence of both high attachment anxiety and avoidance. However, studies of attachment and AVPD have been inconsistent; some studies show only links between attachment avoidance and AVPD (e.g., Westen, Nakash, Thomas, & Bradley, 2006), whereas fewer show only links between attachment anxiety and AVPD (Brennan & Shaver, 1998). In terms of ASPD, attachment avoidance has been linked at times to the disorder, though more frequently, attachment insecurity generally (Nakash-Eisikovits, Dutra, & Westen, 2002), rather than a specific attachment style has been associated with ASPD. This research leads us to hypothesize that BPD would be directly related to attachment anxiety, and more tentatively, that AVPD and ASPD would be related to attachment avoidance.

As described by Bowlby (1982), social learning, particularly in the context of emotional distress, leads to the development of working models of relationships that are activated in times of crisis. At such times, without conscious volition, individuals high in attachment anxiety experience hyperactivation of the attachment system (Main, 1990). Hyperactivating behaviors include excessive proximity seeking, sustaining or exaggerating negative affect and emphasizing helplessness and vulnerability. Various theorists assert that hyperactivating strategies are destructive to controlled cognitive processes supporting reflection on self and others, such as mentalization (Bateman & Fonagy, 2004; Main, 1990). Attachment anxiety also promotes difficulties in capacities for representing the self. Individuals high in attachment anxiety depend excessively on others and have low differentiation between self and close others (Mikulincer & Horesh, 1999). The broader set of social cognitive problems in BPD related to the self is often referred to as identity diffusion, a term introduced by Erikson (1968) to denote a lack of coherent and stable personality, impoverished definition in terms of career and life goals, and inauthenticity. Factor analytic studies of BPD symptoms have found identity diffusion and poor interpersonal functioning represent a core factor of the disorder (e.g., Sanislow, Grilo, & McGlashan, 2000). Thus, impaired mentalization, poor self-other boundaries, and identity diffusion are three potential mediators of the relationship between attachment anxiety and BPD. We hypothesized attachment anxiety and BPD would be mediated by each of these factors. Given the inconsistent findings linking attachment anxiety and ASPD or AVPD, we had no basis to make hypotheses for these symptoms.

Individuals high in attachment avoidance engage in deactivating behaviors when the attachment needs are salient, manifest in denying vulnerability and threat (Main, 1990). Needing to continually solidify oneself as superior and self-reliant, individuals high in attachment avoidance are less likely to find a place of felt security or the cognitive benefits that result from not needing to attend to attachment threats. However, the effects of this strategy on social cognition may not be as destructive to clear thinking or identity-related cognition when compared to attachment anxiety. Theorists suggest individuals high in attachment avoidance are able to maintain some social cognitive capacities, except under higher levels of stress (Fonagy & Luyten, 2009). Research seems to support this assertion. At the same time, other work has found attachment avoidance alters social information processing. Individuals high in attachment avoidance divert attention away from and have more difficulty recalling attachment related information (see Dykas & Cassidy, 2011 for review). In total, the data suggest individuals high in attachment avoidance evidence some impairment in social cognition, though not the disorganization and incoherence associated with attachment anxiety and BPD. Similarly, the disorganization of self associated with attachment anxiety and BPD does not appear to be associated with attachment avoidance. Individuals high in attachment avoidance are concerned with constructing an invulnerable self, which may result in an overt or covert grandiose self-image, and potentially an impoverished self, but not self-incoherence.

Specificity of social cognitive problems

In order to investigate the specificity of attachment-related social cognitive problems in BPD, we examined a structural equation model including BPD, AVPD and ASPD symptoms. The selection of this group of disorders was motivated by a number of considerations. Both AVPD and ASPD are disorders in which attachment difficulties have been implicated (Lorenzini & Fonagy, 2013), and both share high comorbidity with BPD (e.g., Skodol et al., 2002). In addition research suggests a shared environmental and biological risk for BPD and ASPD (Beauchaine & Klein, 2009). Additionally, numerous studies suggest that problems with social cognition, particularly empathic functioning, characterizes ASPD (Sharp & Sieswerda, 2013), and ASPD has considerable public health significance (Glenn, Johnson, & Raine, 2013), comparable to BPD. AVPD shares several characteristics with BPD, most centrally, interpersonal hypersensitivity, and a dynamic of both wanting and fearing rejection within close relationships (Fossati et al., 2003). Further, evaluating what connections these disorders share with BPD in terms of attachment and social cognition is theoretically and clinically compelling.

Current Study

A barrier to understanding social cognitive problems in BPD is the extensive overlap in the conceptualizations of the relevant social cognitive constructs. Our approach was to develop exploratory measurement models of aspects of social cognition, starting with a broad pool of candidate items from our extensive battery of self-report and clinician-rated measures. We used exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses to identify latent constructs and to prune redundant and less useful items. The constructs used as a frame for our search are described in Table 2. Through this data-driven approach, we identified social cognitive factors, which we placed as latent factors within a structural equation model testing whether these factors mediated the relationship between attachment styles and BPD, AVPD and ASPD symptoms.

Table 2.

Results of item-level search for measures of various social cognitive constructs

| Construct | Measure | Aspect Assessed | Example Item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mentalization: ability to understand the behavior of self and others in terms of intentional mental states. Awareness of qualities of mental states (opaqueness, re-evaluation through development, influence of relationships on mental states). | Attachment Q-sort (Kobak, 1989) | Items assessing influence of relationships on relationship, influence of parental mental states on children, opaqueness of mental states | Presents an objective and well thought picture of relationship influences |

| Interpersonal Relations Assessment (Heape et al., 1989) | Overall Score of reflective functioning – clinicians rated participants on ability to identify mental states in self and others, awareness of mental states contributing to behavior and limitations of others in light of their experiences. | See description | |

| Psychological Mindedness/Metacognition: ability to make meaning of experience and behavior by seeing connections between cognition, affect and behavior; thinking about thinking. | Adult Attachment Ratings (Pilkonis, Kim, Yu & Morse, 2013) | Items assessing lack of awareness of behavior on others | Is somewhat oblivious to the effects of his/her actions on other people |

| Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000) | Item assessing obliviousness to why partners change feelings about respondent | Sometimes romantic partners change their feelings about me for no apparent reason | |

| Emotional Experiencing and Regulation Interview (Reynolds, Yaggi, Morse, Stepp & Pilkonis, 2006) | Inability to state links between emotions, thoughts and actions | Unable to state how he/she feels, the link between emotions, thoughts, and actions | |

| Mindfulness: the process of bringing attention to the present moment with the qualities of acceptance, curiosity, and clarity. | Adult Temperament Questionnaire (Evans & Rothbart, 2007) | Items Assessing inability guide attention in face of competing affect and cognition | When trying to focus my attention on something, I have difficulty blocking out distracting thoughts |

| Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) | Items assessing awareness of emotion | I know exactly how I am feeling | |

| NEO PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) | Lack of mindfulness to environment and ways affects mood | I seldom notice the moods or feelings that different environments produce | |

| Affect Consciousness: ability to consciously perceive affective experience and to reflect on and express that experience. | Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) | Items assessing clarity of emotional experience | I am clear about my feelings |

| NEO PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) | Lack of attention to feelings | I seldom pay much attention to my feeling of the moment | |

| Empathy: sharing of emotional states of others and ability to take the perspective of others. | Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureno, & Villasenor, 1988) | Items assessing difficulty with perspective taking and compassion | It is hard for me to understand another person's point of view |

| NEO PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) | Items assessing lack of emotional empathy for less fortunate, selfishness | I have no sympathy for panhandlers | |

| Self-Other Differentiation: boundaries between self and otherin which individual can maintain individuality inside close, emotional relationships, without being overwhelmed by the thoughts and feelings of others. | Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureno, & Villasenor, 1988) | Items assessing difficulties with emotional and cognitive contagion, difficulty spending time alone, feeling like separate person | It is hard for me to feel like a separate person when I am in a relationship |

| Adult Attachment Ratings (Pilkonis, Kim, Yu & Morse, 2013) | Difficulty establishing self outside of relationships (due to dependency needs); difficulty judging own accomplishments (needs others to judge) | Has little sense of “self part from relationships; the development of a strong sense of “self” is interfered with by preoccupations over establishing satisfying interpersonal relationships | |

| Identity Diffusion: lack of definition in terms of self, evident in difficulty expressing a rich or coherent and consistent identity. Feelings of emptiness or lack of authenticity are often believed to be expression of identity diffusion. | Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Features Scale (PAI-BOR; Morey, 1991) | Items assessing inconsistency, impoverishment of identity and emptiness | My attitude about myself changes a lot |

| Adult Attachment Ratings (Pilkonis, Kim, Yu & Morse, 2013) | Item assessing good sense of identity | Has a good sense of his/her identity, but also appreciates the personalities of others and finds pleasure in relating to them | |

Method

Participants and Recruitment Procedures

The sample consisted of 150 adult participants recruited for a study of interpersonal and emotional functioning among individuals with BPD (mean age = 44.9, SD = 10.4, range 22-61; 65% female; see table 1 for demographic information). Potential subjects were screened using the McLean Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD; Zanarini & Vujanovic, 2003), a self-report questionnaire with items based on the BPD module of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorder (DIPD-IV). Recruitment methods were designed to produce a full range of BPD features including individuals in treatment and those not seeking treatment. The recruitment protocol used three strata (0-2, 3-4, or 5 or more diagnostic criteria endorsed on the MSI-BPD) and two groups, community sample (n=75) and psychiatric sample (n=75). The sample had 53 full diagnoses of the three PDs studied, with the following distribution: BPD (n=26), ASPD (n=9), or AVPD (n = 18), with 3 participants having both BPD and ASPD, 4 having both BPD and AVPD and 0 with both ASPD and AVPD. Forty-five participants had at least clinically significant BPD traits (based on clinical judgment), while 29 evidenced ASPD traits and 32 evidenced AVPD traits. This was consistent with our effort to recruit a range of personality pathology. From the community portion of the sample, 4 participants met diagnostic threshold for BPD and 3 met for AVPD. Patients were recruited via flyers in outpatient psychiatric treatment facilities and through research networking systems such as the psychiatric hospital research registry, research coordinator meetings, or direct referrals from outpatient clinics. The community sample was recruited by telephone through the use of random digit dialing (RDD) method. RDD was used to yield a probability sample representative of demographic characteristics reflected in the U.S. census for the Pittsburgh with oversampling of African American participants to ensure racial minority representation that mirrored the local population. Participants with psychotic disorders, organic mental disorders, and mental retardation were excluded, as were participants with major medical illnesses that influence the central nervous system. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Table 1.

| Sample Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| M | 44.85 |

| SD | 10.43 |

| Education N (%) | |

| Education beyond HS | 109 (73%) |

| High School Graduate | 28 (19%) |

| Did not complete HS | 13 (9%) |

| Marital status N (%) | |

| Single | 68 (45%) |

| Married/remaried | 47 (31%) |

| Divorced | 28 (19%) |

| Widowed | 2 (1%) |

| Ethnicity (%) | |

| Caucasian | 86 (57%) |

| African American | 57 (38%) |

| Biracial | 6 (4%) |

| Asian | 1 (1%) |

Assessment Procedures

Diagnostic assessments at intake consisted of three or more sessions for each participant, which included administration of the SCID-I (First, Spitzer, & Williams, 1997), and the SIDP-IV (Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1997) for assessment of Axis-I and Axis-II disorders, respectively. In addition, a detailed social and developmental history was taken, using a semi-structured interview – the Interpersonal Relations Assessment (IRA), developed for this purpose (Heape, Pilkonis, Lambert, & Proietti, 1989). Following assessment, a research team, including at least three judges who reviewed all information collected during the intake process, conducted a consensus diagnostic case conference. Interviewers were trained clinicians who had a master's or doctoral degree and at least 5 years experience. In the current sample, 63.3% of participants met the threshold for a diagnosis of one or more clinical syndromes, the majority of which were mood (73.3%), anxiety (49.5%) and substance related (31.6%) disorders. A majority (56.7%) of the sample met the threshold for a diagnosis of one or more PDs, of which BPD (30.6%) and PD not otherwise specified (30.6%) were the most common.

Attachment insecurity

Styles of attachment insecurity were assessed using the Experience in Close Relationships Scale – Revised (ECR-R; Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000). The ECR-R is a 36-item questionnaire assessing attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance in romantic relationships. Chronbach's alpha for the ECR-R in the present study was .94 for attachment anxiety and .92 for attachment avoidance.

Measuring aspects of social cognition

Social cognitive constructs targeted in this study, spanning both capacities for understanding self and others, are detailed in Table 2. Items selected for consideration were a mix of self-report and clinician-rated items derived from the Personality Assessment Inventory-Borderline Personality Disorder Identity Scale (PAI-BOR; Morey, 1991), the Clarity subscale from the Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004), Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureño, & Villaseñor, 1988), Kobak's Attachment Q-sets (Kobak, 1989), and our own clinician assessment of mentalization.

BPD symptoms

The structural equation model used BPD, AVPD, and ASPD dimensional scores as the dependent variables. Clinician-rated BPD, AVPD, and ASPD symptoms were assessed using a DSM checklist, rated by the consensus team using all available information from intake, including responses on the SIDP-IV (Pfohl, Blum & Zimmerman, 1997). Individual DSM-IV diagnostic criteria were rated on a trichotomous scale and BPD dimensional scores were calculated by summing scores for all BPD criteria. Reliability for ASPD symptoms was .69, for AVPD symptoms was .76 and for BPD symptoms was .80.

Data-Analytic Approach

After a rational search for relevant social cognitive items, measurement models were derived from these items using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. These measurement models were used to construct a cross-sectional structural equation model of potential mediators of the relationship between attachment styles and BPD, ASPD, and AVPD symptoms.

Results

Scale Construction

Thirty-nine items assessing aspects of social cognitive constructs such as mindfulness, mentalization, metacognition, affect consciousness, identity diffusion, self-other differentiation and psychological mindedness were selected from a large battery of measures (see Table 2). An exploratory factor analysis using maximum likelihood estimation and promax rotation was conducted on this initial pool of 39 items. This unconstrained EFA, including all factors with eigenvalues above 1, yielded a 5-factor solution, but included two factors with eigenvalues close to 1, each with only 2 items, indicating the utility of a 3-factor solution. In addition, a majority of items had factor loadings below .4 and the model fit for the EFA was poor. As a next step, we deleted twenty-two items with factor loadings below .40 on any factor and performed a second EFA on the remaining 17 items. The scree plot from this second EFA supported a 3-factor solution. We then performed a CFA on these 17 items in which 3 factors were specified. Three items showed residual correlations larger than r = .25 that reflected similar wording and were deleted for this reason. A final 3-factor CFA was performed on the remaining 14 items, fit statistics indicated an excellent fit was obtained (χ2 = 86.41, p=.153, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, SRMR = .05). The three factors reflected 1) a subjective sense of identity diffusion, 2) self-report of difficulties with boundaries between self and others, and 3) clinician-rated impairments in mentalization. Factors, items, and factor loadings are listed in Table 3. Identity diffusion and self-other boundaries were correlated at r = .69. Mentalization was correlated with identity diffusion at r = −.27 and with self-other boundaries at r = −.45. Correlations between attachment scales and PD symptoms are displayed in table 4.

Table 3.

EFA Factor Loadings

| EFA with Promax Rotation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Self-Other Boundaries | |||

| IIP36 – Hard for me to feel separate from others | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| IIP66 – Affected too much by other's moods | 0.95 | −0.14 | −0.05 |

| IIP69 – I am too gullible | 0.60 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| IIP74 – Influenced too much by others | 0.70 | 0.15 | −0.05 |

| IIP87 – Affected too much by other's misery | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Identity Diffusion | |||

| PAI2 – My attitude about myself changes a lot | 0.12 | 0.59 | 0.03 |

| PAI5 – I often feel terribly empty | −0.01 | 0.89 | 0.01 |

| PAI11 – I wonder what I should do with my life | −0.02 | 0.89 | 0.01 |

| DERS 5 – I have difficulty making sense of my feelings | 0.24 | 0.58 | −0.04 |

| Mentalization | |||

| Q-sort12 – Acknowledges limitations in view of parents | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.78 |

| Q-sort29 – Presents objective picture of relationship influences | −0.07 | 0.11 | −0.91 |

| Q-sort62 – Understands parents’ limitations in light of own experience | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.87 |

| Q-sort65 – Able to discuss the influence of relationships on relationships | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.87 |

| IRA - Reflective Function Total | 0.13 | −0.19 | −0.71 |

All items significant at p < .001. PAI = Personality Assessment Inventory; DERS = Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale; IIP = Index of Interpersonal problems; Q-sort = Kobak's Attachment Q-sort; IRA = Interpersonal Relations Assessment.

Table 4.

Descriptive and Correlations between independent and dependent variables.

| M | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPD dimensional scores | 2.62 | 3.30 | 0 | 14 |

| ASPD dimensional scores | 1.40 | 2.36 | 0 | 10 |

| AvPD dimensional scores | 1.54 | 2.58 | 0 | 12 |

| ECR-R Attachment Anxiety | 3.65 | 1.50 | 1 | 7 |

| ECR-R Attachent Avoidance | 3.28 | 1.22 | 1 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BPD symptoms | ||||

| 2. ASPD symptoms | .44** | |||

| 3. AvPD symptoms | .20* | -.030 | ||

| 4. ECR-R Attachment Anxiety | .47** | .22* | .25* | |

| 5. ECR-R Attachment Avoidance | .33** | .20* | .34** | .40** |

Note

p < .05

p<.001.

ECR-R = Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised.

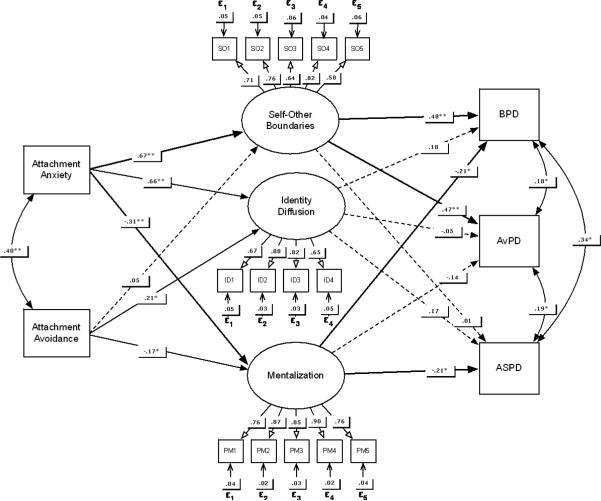

SEM Model

Hypotheses were tested using structural equation models within Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013), using robust maximum likelihood estimation. Using bootstrapping based on 1000 iterations, we computed confidence intervals around parameter estimates for indirect effects. Indirect effects of attachment anxiety on BPD symptoms via social cognitive difficulties were computed as the product of the attachment anxiety → social cognition and social cognition → PD (BPD, ASPD and AVPD) parameter estimates. Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were manifest independent variables using the ECR-R scales, and the dependent variables (BPD, AVPD, and ASPD dimensional scores) were assessed with the clinician-rated DSM checklist from the consensus diagnostic conference. The three latent variables described above served as potential mediators. A diagram of the model is presented in Figure 1. For the full model, 4 of 5 fit statistics indicated excellent fit, χ2 (130) = 162.57, p = .028, RMSEA=.04, CFI=.98, TLI = .97 SRMR = .04. Attachment avoidance was directly related to AVPD symptoms, β = .29, 95% CI = .06 - .44, z = 3.72, p < .001. Specific indirect effects from attachment anxiety to BPD dimensional scores were significant for 2 of the 3 potential mediators: self-other boundaries and mentalization. The indirect path from attachment anxiety, through self-other boundaries, to BPD was significant, Δβ =- .33, 95% CIs = .12-.54, z = 3.015, p = .003, as was the indirect path from attachment anxiety, through mentalization to BPD, Δβ = -.06, 95% CIs = .02-.12, z = 2.21, p = .027 (Δβ represents decrease in regression coefficients of direct effect due to indirect effect). On the other hand, none of the latent factors mediated the relationship between attachment avoidance and BPD. Both AVPD and ASPD evidenced one significant indirect path. Attachment anxiety was indirectly related to ASPD symptoms through mentalization, Δβ = -.07, 95% CIs = .01 - .12, z = 1.95, p = .051, while attachment anxiety was indirectly related to AVPD symptoms through self-other boundaries, Δβ = -.33, 95% CIs = .10 - .56, z = 2.79, p = .005. See Figure 1 for the model and Table 5 for specific indirect effects.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model.

Note. Bolded lines indicate significant indirect effects. Direct effects between IVs and DVs were estimated, and all mediators were allowed to correlate, though these paths were not included in the model diagram for readability. Non-significant paths could be removed from the model without significant reduction in model fit; they are left in here in for illustrative purposes.

Table 5.

Effects from ECR-R Attachment Anxiety and Attachment Avoidance to BPD, AvPD, and ASPD Dimensional Scores

| Attachment Anxiety and BPD | Estimate | S.E. | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | .40 | .07 | <.001 |

| Total Indirect | .51 | .09 | <.001 |

| Specific Indirect | |||

| ECRanx → Self-Other → BPD | .33 | .09 | <.001 |

| ECRanx → Identity → BPD | .12 | .09 | .19 |

| ECRanx → Mentalization → BPD | .06 | .03 | .029 |

| ECRanx → BPD | −.11 | .11 | .315 |

| Attachment Avoidance and BPD | Estimate | S.E. | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | .17 | .08 | .023 |

| Total Indirect | .10 | .05 | .059 |

| ECRav → Self-Other → BPD | .03 | .04 | .485 |

| ECRav → Identity → BPD | .04 | .03 | .226 |

| ECRav → Mentalization → BPD | .04 | .02 | .107 |

| ECRav → BPD | .08 | .07 | .297 |

| Attachment Anxiety and AvPD | Estimate | S.E. | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | .14 | .08 | .103 |

| Total Indirect | .33 | .10 | .001 |

| Specific Indirect | |||

| ECRanx → Self-Other → AvPD | .33 | .10 | .001 |

| ECRanx → Identity → AvPD | −.04 | .10 | .725 |

| ECRanx → Mentalization → AvPD | .04 | .03 | .148 |

| ECRanx → AvPD | −.20 | .13 | .155 |

| Attachment Avoidance and AvPD | Estimate | S.E. | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | .29 | .08 | <.001 |

| Total Indirect | .04 | .05 | .416 |

| Attachment Anxiety and ASPD | Estimate | S.E. | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | .17 | .09 | .045 |

| Total Indirect | .19 | .11 | .075 |

| Specific Indirect | |||

| ECRanx → Self-Other → ASPD | .01 | .10 | .929 |

| ECRanx → Identity → ASPD | .12 | .11 | .289 |

| ECRanx → Mentalization → ASPD | .07 | .03 | .051 |

| ECRanx → ASPD | −.02 | .13 | .894 |

Note. Total effects represent direct effect prior to controlling for mediators. Direct paths after controlling for mediators are listed on the last line of each section of the table (e.g., ECRanx <- BPD). Attachment avoidance and ASPD, and specific indirect effects of attachment avoidance and AvPD details were omitted for brevity because no significant effects were present. ECRanx = Experiences in Close Relationships Attachment Anxiety Scale. ECRav = Experience in Close Relationship Attachment Avoidance Scale. Paths for Attachment Avoidance and ASPD were omitted because no significant paths were present.

An alternative model that treated attachment styles as mediators of social cognition–PD relationships was tested to further corroborate the hypothesized model. Because the models were not nested, AIC was used as the primary indicator of relative model fit, with an AIC difference of 10 points or more between models (Burnham & Anderson, 2002) indicating substantial difference in fit. The AIC for the hypothesized model was 8438.16. The AIC for the alternative model was 9452.92. The alternative model was close to 1000 points higher, indicating that the hypothesized model in which social cognition mediated relationships between attachment and PD symptoms accounted for the data much better than alternative model.

Discussion

We identified social cognitive mediators potentially relevant to BPD using factor analyses of items selected from a large bank of measures, which resulted in 3 factors frequently mentioned in the theoretical literature. Factor 1 represented clinician-evaluated mentalization, the ability to understand the behavior of others in terms of mental states, such as thoughts, intentions, desires, and relationship influences. Factor 2 represented disturbed self-other boundaries, including difficulties with emotion contagion and feeling separate from others. Factor 3 represented a subjective sense of identity diffusion, which included a lack of certainty regarding feelings, attitudes about self, and emptiness. Using SEM, we found that both mentalization and self-other boundaries mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and BPD symptoms, whereas mentalization mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and ASPD symptoms, and self-other boundaries mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and AVPD.

Though attachment anxiety has been linked both conceptually and empirically to BPD (e.g., Scott et al., 2013), what has been less clear are ways in which attachment anxiety may alter social cognition in BPD. The current study offers evidence that two factors that link attachment anxiety and BPD symptoms are impaired mentalization and disrupted self-other boundaries. In addition, these relationships were specific to attachment anxiety, as none of the indirect effects of attachment avoidance on BPD via social cognition were significant. In addition, though mentalization mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and ASPD symptoms and self-other boundaries mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and AVPD, BPD was distinct in that symptoms were mediated by both variables.

As noted, mentalization mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and both ASPD and BPD symptoms. These two disorders share the commonality of being considered severe personality disorders (Kernberg, 1985), in which social cognitive disturbances have been routinely proposed (e.g., Sharp & Sieswerda, 2013). That ASPD symptoms were not also associated with problems with self-other boundaries is understandable, given the lack of compassion and empathy often associated with the disorder. Problems with self-other boundaries are thought to affect higher-level empathic understanding (Decety & Moriguchi, 2007). Individuals with BPD often become overwhelmed with the affect of others, and show reduced cognitive empathy. However, becoming overwhelmed by the emotion of others is thought to depend on high emotional empathy (Decety & Moriguchi, 2007), whereas ASPD is characterized by social distance and cold-heartedness. Thus, confusing the distinction between self and other likely depends on the desire and capacity to empathize with others’ thoughts and emotions.

The relationship between attachment anxiety and BPD and AVPD was mediated by problems with self-other boundaries, suggesting attachment anxiety may manifest in these disorders in the form of problems maintaining one's own views and emotional clarity in the face of others’ experiences. Both of these disorders share the feature of interpersonal hypersensitivity, which, in addition to being associated with attachment anxiety (Gunderson & Lyons-Ruth, 2008), may explain this common pathway to both sets of symptoms. However, the meaning of problems with self-other boundaries may not be uniform when comparing BPD and AVPD. The severe disturbance of self in BPD may signal not just sensitivity to others’ emotions, but a difficulty discerning one's own emotions from those of another. Considering the dual presence of mentalizing and self-other boundary difficulties in BPD, at the very least, BPD should be associated with a more severe disturbance, with the added burden of having difficulty making sense of what is happening when one adopts the thoughts, roles or emotions of others (e.g., tracking that another person's bad mood has overwhelmed oneself, rather than having confusion about where the mood generated). For AVPD, problems with self-other boundaries may reflect a hypersensitivity to others’ emotions and problems with asserting oneself for fear of rejection. For BPD, problems with self-other boundaries may be more severe, becoming overwhelmed by others without clear awareness of the specific transactions, other than a vague knowledge that “I lose myself with close others”. More research will be needed to further understand these important subtleties, which carry implications for treatment.

The specific mix of problems with mentalization and self-other boundaries may help to explain the character of BPD. ASPD symptoms were mediated by problems with mentalization, which is consistent with previous proposals (e.g., Taubner, White, Zimmermann, Fonagy, & Nolte, 2013). However, ASPD symptoms were not mediated by self-disturbance, here operationalized as self-other boundaries and identity diffusion. Thus, ASPD symptoms are predicted by problems with understanding self and others in terms of mental states, but not attachment related deficits with self. AVPD symptoms were predicted by self-other boundaries. However, AVPD symptoms were not associated with attachment related deficits in mentalization, suggesting an intact ability to understand oneself and others in terms of mental states. The dual presence of attachment-related difficulties in self-other boundaries and mentalization may help to explain the profound difficulties in interpersonal functioning that define BPD - severe self instability and problems understanding a chaotic interpersonal world.

While anxious attachment was associated with all of the latent variables, and through at least one indirect path to each PD symptom category, associations with avoidant attachment were more limited. Avoidant attachment was directly associated with AVPD. This is consistent with some previous studies (Brennan & Shaver, 1998; Fossati et al., 2003; Westen et al., 2006), though other studies have found no association (Nakash-Eisikovits et al., 2002; Westen et al., 2006). Westen and colleagues (2006) found within the same study both an association between attachment avoidance and avoidant PD in adolescents and no association between the two in adults. Such inconsistencies may reflect the heterogeneity of AVPD. AVPD is characterized as both self-imposed withdrawal from social life, and emotional distance due to deep feelings of inferiority, consistent with attachment avoidance, as well as a deep longing for relationships and rejection sensitivity, consistent with attachment anxiety. Attachment avoidance also had a small association with mentalization, which was consistent with our hypotheses, based on theory and research that suggests individuals high in attachment avoidance do not benefit from the cognitive benefits of felt security (e.g., Fonagy & Luyten, 2009), but also do not experience the disorganizing incoherence associated with attachment anxiety.

As anticipated, none of the latent variables mediated the relationship between attachment avoidance and BPD symptoms, which is consistent with the above idea that attachment anxiety, rather than attachment avoidance is more closely associated with more severe cognitive disorganization and self-dysfunction. Consistent with the current results, attachment avoidance is a less prominent feature of BPD (e.g., Scott, Levy, & Pincus, 2009) and not as strongly associated with mediators identified here. Individuals with BPD tend to vacillate between intense need for care and angry attempts at self-sufficiency (Melges & Swartz, 1989), though the more preoccupied aspects of those oscillations are generally considered to be more pronounced (e.g., Agrawal, Gunderson, Holmes, & Lyons-Ruth, 2004).

Strengths and Limitations

A number of strengths and limitations should be noted for the current study. The use of multiple methods of assessment (clinician rated and self-report) represents a strength of the research design, making it unlikely that the results are due simply to method variance. In addition, the use of advanced modeling techniques allowed for both data-driven measures of social cognitive constructs, and the simultaneous assessment of multiple mediators thought to be important to BPD. Another strength is that we tested multiple social cognitive constructs within the same model, allowing each to compete for variance in the model and disambiguate which factors offer unique relations with each diagnosis. An important limitation is that, because individuals with features of BPD were targeted for recruitment, the current results may differ in samples that include a broader representation of other PDs, including our comparators, AVPD and ASPD. However, because of the high comorbidity of AVPD, ASPD and BPD, the present sample includes ample variance for each of these symptom categories. Thus, the specificity for pathways to different PD symptoms within a BPD sample can be explored, with the caveat that a more broadly selected sample may evidence different characteristics. Another limitation is that the latent factors representing self-other boundaries and identity diffusion shared a large association. The absence of an indirect effect through identity diffusion to BPD does not necessarily mean the variable is unimportant in explaining attachment related problems in BPD, but it could indicate instead that the variance that it explains related to BPD is accounted for by other variables. This competition for variance among factors is a strength of the simultaneous estimation offered by structural equation modeling. Lastly, objective performance-based tasks of self and mentalization could be vital in future research.

Conclusion

There is considerable theoretical interest in the relationships between attachment, social cognition, and BPD. This study improves our understanding of the links between attachment, mentalization, self-other disturbance, and BPD by suggesting that social cognition is the proximate link to BPD by which attachment anxiety has its effects. Major treatments for BPD are consistent in their focus on impairments in these areas. Additional work is needed to identify which specific interventions improve mentalization and self-other differentiation that may lead to improvement in other aspects of BPD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (F32 MH102895, PI: Joseph E. Beeney and R01 MH05688, PI: Paul A. Pilkonis).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Agrawal HR, Gunderson J, Holmes BM, Lyons-Ruth K. Attachment studies with borderline patients: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2004;12(2):94–104. doi: 10.1080/10673220490447218. doi:10.1080/10673220490447218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S. The syndrome of identity diffusion. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(11):1381–1385. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Kwong MJ, Hart SD. Attachment. In: Livesley WJ, editor. Handbook of personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2001. pp. 196–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonagy P. Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Mentalization-based treatment. Oxford University Press; USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine T, Klein D. Multifinality in the development of personality disorders: A Biology× Sex× Environment interaction model of antisocial and borderline traits. Development and. 2009;21(3):735–70. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000418. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Attachment. Vol. 1. Basic Books (AZ); 1982. doi:Bowlby. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan K. a, Shaver PR. Attachment styles and personality disorders: their connections to each other and to parental divorce, parental death, and perceptions of parental caregiving. Journal of Personality. 1998;66(5):835–78. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00034. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9802235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham K, Anderson D. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. 2002 Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=fT1Iu-h6E-oC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&ots=tert20_Bq7&sig=5E47xP_Jj-mOzLIYaD44oq1oYNw.

- Costa P, McCrae R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Moriguchi Y. The empathic brain and its dysfunction in psychiatric populations: implications for intervention across different clinical conditions. Biopsychosoc Med. 2007;1:22. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-1-22. doi:10.1186/1751-0759-1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykas MJ, Cassidy J. Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: theory and evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(1):19–46. doi: 10.1037/a0021367. doi:10.1037/a0021367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziobek I, Preissler S, Grozdanovic Z, Heuser I, Heekeren HR, Roepke S. Neuronal correlates of altered empathy and social cognition in borderline personality disorder. Neuroimage. 2011;57(2):539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.005. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity, youth, and crisis. W. W. Norton; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DE, Rothbart MK. Developing a model for adult temperament. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(4):868–888. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.11.002. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders SCID-I: clinician version, administration booklet. American Psychiatric Pub; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Luyten P. A developmental, mentalization-based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(4):1355–1381. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990198. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Feeney J. a., Donati D, Donini M, Novella L, Bagnato M, Maffei C. Personality Disorders and Adult Attachment Dimensions in a Mixed Psychiatric Sample: a Multivariate Study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191(1):30–37. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200301000-00006. doi:10.1097/00005053-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan K. a. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78(2):350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn AL, Johnson AK, Raine A. Antisocial personality disorder: a current review. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2013;15(12):427. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0427-7. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(1):41–54. doi:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, Lyons-Ruth K. BPD's interpersonal hypersensitivity phenotype: a gene-environment-developmental model. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(1):22–41. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.22. doi:10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heape CL, Pilkonis PA, Lambert J, Proietti J. Interpersonal Relations Assessment. 1989 Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureño G, Villaseñor VS. Inventory of interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):885–92. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.885. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3204198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg OF. Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. Rowman & Littlefield; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR. The Attachment Interview Q-set. University of Delaware; Newark, DE.: 1989. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzini N, Fonagy P. Attachment and personality disorders: a short review. FOCUS: The Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry. 2013;11(2):155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Cross-Cultural Studies of Attachment Organization: Recent Studies, Changing Methodologies, and the Concept of Conditional Strategies. Human Development. 1990;33(1):48–61. doi:10.1159/000276502. [Google Scholar]

- Melges FT, Swartz MS. Oscillations of attachment in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(9):1115–1120. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.9.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, Pilkonis PA. An attachment model of personality disorders. Major Theories of Personality Disorder. 2005;2:231–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Horesh N. Adult attachment style and the perception of others: the role of projective mechanisms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(6):1022. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.6.1022. Retrieved from syncii:///Mikulincer 1999 Adult attachment style and the per.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Dynamics, and Change. Guilford Press; 2007. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure; p. 578. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=BDF6Pdc_7LQC&pgis=1. [Google Scholar]

- Morey . Psychological Assessment Inventory. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nakash-Eisikovits O, Dutra L, Westen D. Relationship between attachment patterns and personality pathology in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(9):1111–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00012. doi:10.1097/00004583-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality. American Psychiatric Pub; 1997. p. 38. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books/about/Structured_Interview_for_DSM_IV_Personal.html?id=J17zkm2RH6MC&pgis=1. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Kim Y, Yu L, Morse JQ. Adult Attachment Ratings (AAR): An Item Response Theory Analysis. J Pers Assess. 2013 doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.832261. doi:10.1080/00223891.2013.832261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH. Factor analysis of the DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1629–1633. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LN, Levy KN, Pincus AL. Adult attachment, personality traits, and borderline personality disorder features in young adults. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23(3):258–80. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.3.258. doi:10.1521/pedi.2009.23.3.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Sieswerda S. The social-cognitive basis of borderline and antisocial personality disorder: introduction. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2013;27(1):1–2. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2013.27.1.1. doi:10.1521/pedi.2013.27.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley CG, Fischer R, Liu JH. Reliability and validity of the revised experiences in close relationships (ECR-R) self-report measure of adult romantic attachment. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;31(11):1524–1536. doi: 10.1177/0146167205276865. doi:10.1177/0146167205276865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, Siever LJ. The borderline diagnosis I: psychopathology, comorbidity, and personaltity structure. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):936–950. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01324-0. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Waters E. Attachment as an Organizational Construct. Child Development. 1977;48(4):1184. doi:10.2307/1128475. [Google Scholar]

- Taubner S, White LO, Zimmermann J, Fonagy P, Nolte T. Attachment-related mentalization moderates the relationship between psychopathic traits and proactive aggression in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(6):929–38. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9736-x. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9736-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, Nakash O, Thomas C, Bradley R. Clinical assessment of attachment patterns and personality disorder in adolescents and adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(6):1065–85. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1065. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini M, Vujanovic A. A screening measure for BPD: The McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). Journal of Personality. 2003;17(6):568–73. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14744082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]