Abstract

Background & Aims

High-resolution manometry (HRM) expands recognition of minor esophageal motor abnormalities, but the clinical significance of these is unclear. We aimed to determine the outcomes of minor esophageal motor abnormalities.

Methods

We reviewed HRM tracings from individuals who underwent esophageal manometry at Northwestern Memorial Hospital from July 2004 through October 2005, using the Chicago classification (version 2.0). We identified 301 patients with normal findings or minor manometric abnormalities (weak peristalsis, hypertensive peristalsis, frequent failed peristalsis, or rapid contractions with normal latency). Ninety-eight patients participated in a phone survey in which they were asked questions from the impact dysphagia questionnaire (IDQ; mean follow-up period: 6 years 5 months).

Results

Of 301 the patients assessed, 166 had normal findings from HRM, 82 had weak peristalsis, 34 had hypertensive peristalsis, 17 had frequent failed peristalsis, and 2 had rapid contractions with normal latency. The primary indications for HRM of dysphagia (44%) and gastroesophageal reflux (63%) were unrelated to manometric findings. There were no endoscopic or video-fluoroscopic differences between patients with minor manometric abnormalities. Of 98 patients with follow up, findings from HRM were normal in 63, weak peristalsis was observed in 23, hypertensive peristalsis in 10, and frequent failed peristalsis in 2. No patients underwent surgical myotomy, pneumatic dilation, or botulinum toxin injection. Use of proton-pump inhibitors and rates of fundoplication were similar, regardless of manometric findings. Sixteen patients (16%) had significant dysphagia at follow up; hypertensive peristalsis was the most likely to be symptomatic.

Conclusion

Patients with normal and minor esophageal motor abnormalities report minimal symptoms and have few medical interventions related to esophageal dysfunction during long-term follow up. Identification of normal and minor motor function is therefore likely a good prognostic indicator.

Keywords: Chicago classification, weak peristalsis, nutcracker esophagus, minor manometric abnormalities

Background

In contrast to conventional manometry, high resolution manometry (HRM) utilizes an increased number of esophageal pressure sensors positioned closely to allow intraluminal pressure to be monitored as a continuum. This in turn allows manometric data to be displayed as pressure topographic plots and facilitates the simultaneous analysis of different contractile segments of the esophagus and in essence a more precise definition of contractile characteristics of the esophagus. However, the increased information amassed by HRM falls beyond the limits of conventional manometric classification systems, presenting a diagnostic challenge. The Chicago classification attempts to address this need by providing a new system in which to group esophageal motor disorders identified with high resolution manometry.1

However, while major motor abnormalities such as achalasia and aperistalsis carry indisputable clinical significance, they are less common than normal studies or minor motor abnormalities such as weak or hypertensive peristalsis, for which the clinical significance is less clear. In fact, these findings are commonly observed in healthy volunteers and often correlate with normal bolus transit. 2,3

To date there is limited data on the natural history and long term outcomes for patients evaluated initially with conventional and high resolution manometry (HRM). Previous studies are small and did not utilize the Chicago classification.4,5 However, despite this some have suggested an association between weak esophageal peristalsis and gastroesophageal reflux (GERD).6–8 Other studies have also suggested that minor motor abnormalities may be precursors to major motor abnormalities such as achalasia.9 We sought to define the natural history of patients with normal findings and minor manometric abnormalities found initially on high resolution esophageal manometry.

Methods

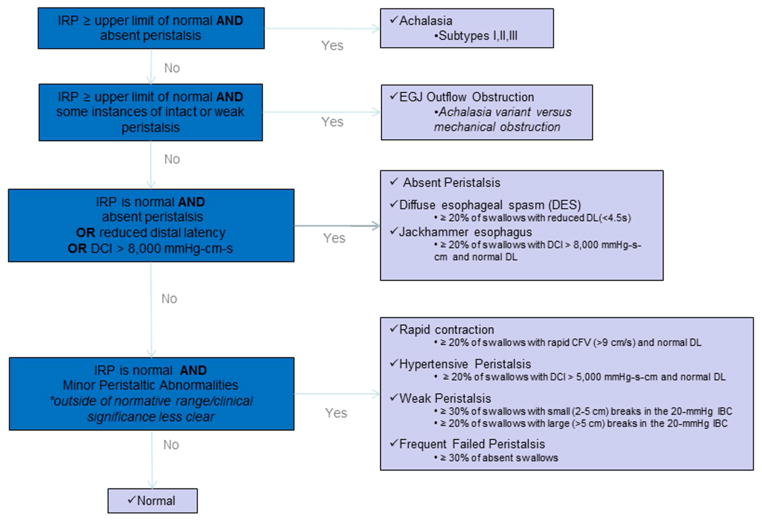

The study was approved by the Northwestern Memorial Hospital institutional review board. This was a retrospective cohort study. Patients between the ages of 18 and 90 years old who were referred to Northwestern Memorial Hospital for a clinically indicated high resolution esophageal manometry study between July 2004 and October 2005 were identified. Esophageal manometry had been performed as per a standard protocol. A solid-state esophageal manometry catheter with 36 circumferential sensors spaced 1cm apart was placed transnasal. Studies were done in both an upright seated and supine position, with ten liquid swallows in each position. Study interpretation was based on swallows while in the supine position. Those under the age of 18 years old, a history of previous upper gastrointestinal surgery, prior esophageal endoscopic dilation or surgical lower esophageal sphincter myotomy, esophageal stricture, or a technically inadequate manometry study were excluded. All studies were reviewed by a single investigator (KR) and classified per the Chicago classification criteria (version 2.0).1 Those with major manometric abnormalities, defined by the Chicago classification scheme as achalasia, gastroesophageal junction outflow obstruction, absent peristalsis, distal esophageal spasm, and hypercontractile (jackhammer) esophagus were excluded. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

The Chicago Classification (version 2.0)

Clinical notes were reviewed to assess clinical characteristics, endoscopic findings, and radiographic features. Identified study subjects were contacted for a phone survey utilizing the impact dysphagia questionnaire (IDQ).3 (Figure 2) The IDQ is a tool consisting of 10 questions to assess dysphagia with a total score range of 0 to 50. The IDQ has previously been utilized in studies to assess dysphagia.3 Recently the IDQ has been validated by our group in over 1000 patients, with a score of greater than or 7 serving as a cut-off for abnormal motor function. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the overall patient cohort. Comparison between patients groups was made using the student t test and Chi Square test.

Figure 2.

Impact Dysphagia Questionnaire (IDQ)

Results

Index Manometric and Clinical Findings

A total of 507 patients who underwent high resolution esophageal manometry at Northwestern Memorial hospital between July 2004 and October 2005 were identified. After excluding those not meeting inclusion criteria, a total of 301 eligible patients were found. (Figure 3) The most common manometric finding was normal, seen in 166 patients. Of the 135 patients with minor manometric abnormalities 55 had weak peristalsis with small peristaltic defects, 27 had weak peristalsis with large peristaltic defects, 34 had hypertensive peristalsis (nutcracker esophagus), 17 had frequent failed peristalsis, and 2 had rapid contractions with normal latency. (Table 1)

Figure 3.

Patient selection

Table 1.

Indications for HRM*

| Normal | Minor | Weak Peristalsis | Weak peristalsis small break | Weak peristalsis large break | Frequent failed peristalsis | Hypertensive esophagus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 166 | 135 | 82 | 55 | 27 | 17 | 34 |

| Dysphagia | 67 (40.4%) | 65 (48.1%) | 37 (45.1%) | 23 (41.8%) | 14 (51.9%) | 10 (58.8%) | 17 (50%) |

| GERD# | 104 (62.7%) | 87 (64.4%) | 55 (67.1%) | 36 (65.5%) | 19 (70.4%) | 9 (52.9%) | 23 (67.6%) |

| Chest Pain | 45 (27.1%) | 42 (31.1%) | 23 (28%) | 16 (29.1%) | 7 (25.9%) | 6 (35.3%) | 13 (38.2%) |

| Dyspepsia/Globus | 20 (12%) | 19 (14.1%) | 12 (14.6%) | 8 (14.5%) | 4 (14.8%) | 3 (17.6%) | 3 (8.8%) |

Individual patients may have multiple indications for HRM

Includes heartburn, acid regurgitation, and extraesophageal symptoms of GERD

p<0.05 when compared to patients with normal esophageal manometry

p<0.001 when compared to patients with normal esophageal manometry

Clinical data for the cohort are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Patients with minor manometric abnormalities were older than those with normal esophageal manometry, consistent among all subtypes except frequent failed peristalsis. However symptoms at presentation, as defined by indication for the study, were similar among groups. Gastroesophageal reflux was the most common indication reported in 63% of patients, with 44% reporting dysphagia, 29% chest pain, and 13% dyspepsia or globus. (Table 1)

Table 2.

Clinical features at HRM

| Normal | Minor | Weak Peristalsis | Weak peristalsis small break | Weak peristalsis large break | Frequent failed peristalsis | Hypertensive esophagus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 69.3% (115/166) | 65.9% (89/135) | 65.9%(54/82) | 72.7% (40/55) | 51.9% (14/27) | 52.9% (9/17) | 70.6% (24/34) |

| Age (years) | 46.9 (18.6– 87.4) | 55.3‡ (20.2– 86.7) | 56.5‡ (20.2–86.7) | 55.6‡ (20.2– 86.7) | 58.4† (27.7– 85.6) | 49.5 (25.9– 78.2) | 54.2‡ (31.1–83) |

| Esophagitis/Barrett’s* | 10.4% (12/115) | 7.9% (8/101) | 11.3% (7/62) | 11.1% (5/45) | 11.8% (2/17) | 7.1% (1/14) | 0% (0/25) |

| Abnormal emptying on esophagram# | 13.8% (4/29) | 27.6% (8/29) | 21.1% (4/19) | 14.3% (2/14) | 40% (2/5) | 0% (0/3) | 57.1%† (4/7) |

LA Grade A-D reflux esophagitis or histologically confirmed Barrett’s

Abnormal peristalsis or delayed passage of a 13mm barium tablet

p<0.05 when compared to patients with normal esophageal manometry

p<0.001 when compared to patients with normal esophageal manometry

Testing at the Time of High Resolution Manometry

Adjunct diagnostic testing was performed at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in the majority of patients, with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) performed in 216 (72%) and esophagram in 48 (16%). No differences in endoscopic findings existed between those with normal and borderline abnormal manometry studies, with 66% reported as having completely normal studies while only 9% had endoscopic evidence of reflux esophagitis or Barrett’s mucosa. No patients had evidence of eosinophilic esophagitis. Esophagography was similarly normal in the majority of patients, however abnormal emptying and abnormal peristalsis were identified on esophagram in 14% and 3% of those with normal studies in contrast to 28% and 10% of patients with minor manometric abnormalities respectively. This difference was not significant, however (p=0.2 and 0.4 respectively). (Table 2)

Long-term follow- up

Of the 301 eligible patients, 98 (33%) completed a phone survey to assess long term outcome. While constituting a minority of patients, this group was representative of the cohort. Specifically, 68% and 64% of patients were female (p=0.49) with a mean age of 53 years old and 51 years old (p=0.2) among patients with and without long-term follow up respectively. The indications for esophageal manometry were also similar, with dysphagia in 46% and 48% (p=0.79), GERD in 63% and 63 % (p=0.97), chest pain in 26% and 29% (p=0.64), and dyspepsia or globus in12% and 14% (p=0.62) of patients with and without long-term follow up respectively. Finally, manometric findings were representative of the entire cohort, with 36% with minor manometric findings compared to 45% in the entire study cohort (p=0.13), 23% with weak peristalsis compared to 27% in the entire study cohort (p=0.51), and 10% with hypertensive peristalsis compared to 11% in the entire study cohort (p=0.85).

The time of follow up was 5.7to 7 years (mean 6.4 years). Initial esophageal manometry was normal in 63 patients and demonstrated minor motor abnormalities in 35. Of those with minor manometric abnormalities, 13 had weak peristalsis with small peristaltic defects, 10 weak peristalsis with large peristaltic defects, 10 hypertensive peristalsis (nutcracker esophagus), and 2 frequent failed peristalsis. Symptoms in patients with minor manometric abnormalities mirrored those with normal esophageal manometry. Specifically, dysphagia was reported in 17.5% and 17.1% and food impaction in 0% and 2.9% of patients with normal and minor motor abnormalities respectively. Further, food avoidance at follow up was exclusively reported in patients with normal index esophageal manometry studies. The majority of patients did not report any weight loss within 6 months of contact, reported in only 22.2% and 20% of patients with normal and minor manometric abnormalities respectively. More than 65% of patients were completely asymptomatic at follow up, reflected by an IDQ score of 0. Notably, a greater proportion of patients with minor manometric abnormalities were asymptomatic than those with normal studies (71.4% versus 61.9%, p=0.3). Only 16 patients reported significant symptoms as reflected by an IDQ score greater than or equal to 7, including 9 (14%) with normal studies and 7 (20%) with minor manometric abnormalities (p=0.46). However, patients with hypertensive peristalsis were more likely to be symptomatic at follow up compared to those with normal studies (40% versus 14%, p=0.048). (Table 3)

Table 3.

Symptoms at follow up

| Normal | Minor | Weak peristalsis | Weak peristalsis small break | Weak peristalsis large break | Hypertensive esophagus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 63 | 35 | 23 | 13 | 10 | 10 |

| Follow up duration | 6.4 (5.9– 7) | 6.4 (5.8–7) | 6.3 (5.8– 7) | 6.3 (5.8– 7) | 6.4 (5.8– 6.8) | 6.5 (5.8–6.9) |

| Weight loss* | 14 (22.2%) (13.4 lbs, 1–34) | 7 (20%) (18.3 lbs, 2– 80) | 3 (13%) (9.3lbs, 2–20) | 3 (23.1%) (9.3lbs, 2–20) | 0 (0%) | 4 (40%) (25lbs, 5–80) |

| Solid food dysphagia# | 11 (17.5%) | 6 (17.1%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (40%) |

| Food impaction╪ | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1† (10%) |

| Meat/bread avoidance | 3 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| IDQ score | 2.2 (0–23) | 4.1 (0–39) | 2.5 (0–39) | 4 (0–39) | 0.6† (0–6) | 6.8 (0–25) |

| IDQ≥7 | 9(14.3%) | 7 (20%) | 2(8.7%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 4† (40%) |

| IDQ = 0 | 39 (61.9%) | 25 (71.4%) | 19 (82.6%) | 10 (76.9%) | 9/10 (90%) | 5 (50%) |

Any reported weight loss within over the preceding 6 months

Greater than once a month in the preceding 30 days

One or more episodes of food sticking for greater than 30 minutes in the preceding year

p<0.05 when compared to patients with normal esophageal manometry

p<0.001 when compared to patients with normal esophageal manometry

Treatment strategies employed during the follow up period were similar among all patients regardless of manometric findings. No patients were treated with surgical myotomy, esophagectomy, or pneumatic dilation. Through the endoscope dilation was performed in 3% of patients with both normal esophageal manometry and minor manometric abnormalities respectively. Antireflux surgery with either surgical or transoral endoscopic fundoplication was rare, seen in 8% and 3% of patients with normal studies and minor manometric abnormalities respectively. Medical antireflux therapy was also similar between groups, with PPI therapy administered in 52% and 57% of patients with normal and minor abnormal studies.

Perceptive symptoms such as chest pain appeared rare at follow up. This is illustrated by the fact that only 17 patients reported use of pain medications at follow up, of which 10 were on opiates and 7 on NSAIDs. Further, this did not appear to correlate with manometric findings as 13 of these had a normal esophageal manometry, while only 2 had hypercontractile esophagus, 1 frequent failed peristalsis, and 1 weak peristalsis. Further, antidepressants were equally uncommon, reported in only 19 patients. Again, this did not appear to correlate with manometric abnormalities as 14 of these had normal findings on esophageal manometry, while only 3 had hypercontractile esophagus and 2 weak peristalsis.

Comparison of patients with specific minor manometric abnormalities and normal studies

No differences were seen among patients with weak peristalsis, frequent failed peristalsis, or rapid contractions with normal latency when individually compared to those patients with normal studies. However, 57% of those with hypertensive peristalsis had abnormal emptying compared to only 14% of those with normal manometry (p=0.01). In addition fewer patients with nutcracker esophagus were asymptomatic, as reflected by an IDQ score of 0, although this did not reach statistical significance (50% versus 61.9%, p=0.47). (Table 2)

Comparison of asymptomatic patients and those with persistent symptoms

Manometric findings did not differ among patients reporting persistent symptoms compared to those who were asymptomatic at follow up. In addition, no significant clinical differences existed between these groups. Patients were largely female in both groups (66% versus 78%, p=0.27), were of similar age (54 versus 51 years old, p=0.4), and had similar rates of dysphagia at presentation (42% versus 30%, p=0.25). In addition, endoscopic (83% versus 95%, p=0.19) and esophagram (73% versus 57%, p=0.45) findings were largely normal at presentation regardless of long-term outcome.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to better define the clinical significance of minor manometric abnormalities identified on high resolution esophageal manometry. The finding of a normal study or minor manometric abnormality constitutes the majority of patients seen in clinical practice. 1 In fact, the original iteration of the Chicago classification described a cohort of 396 patients in which esophageal manometry revealed normal findings in 33%, weak peristalsis in 18%, and nutcracker in 8%; while only 1.5% had distal esophageal spasm and jackhammer esophagus respectively.10 However, the clinical significance of such findings remains largely unclear.

In this study, patients with normal findings and those with minor motor abnormalities had similar symptoms as reflected by study indication. This in and of itself is not surprising, as this cohort represented symptomatic patients undergoing clinically indicated studies. However, GERD was the most frequent indication for esophageal manometry. Dysphagia was a reported indication in the minority of patients and was no more frequent in patients with minor motor abnormalities, arguing against a symptomatic association with the finding of a minor manometric abnormality. A similar dissociation between manometric findings and symptoms was described by Xiao et al, identifying similar manometric findings among swallows with and without associated symptoms.5 In addition, no differences in videofluoroscopy were observed within our cohort. This finding reinforces previous reports showing poor correlation between symptoms, bolus transit, and manometric findings of weak peristalsis or ineffective esophageal motility.2,11

Interestingly, despite previous reports of an association between GERD and findings such as weak peristalsis and nutcracker esophagus, our study failed to demonstrate an increased prevalence of erosive esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus in this group. There are several potential explanations for this. First, it may be that these manometric findings have poor correlation with GERD. In fact, reports on the true association of GERD and minor manometric findings are conflicting, with several studies finding no clear relationship.12,13 A second possibility is that our study failed to identify all the patients with GERD. Ambulatory pH data was not available for our cohort and while erosive esophagitis was largely absent, it is unclear how many patients were on PPIs at the time of EGD. However, at long term follow up PPI use was no different among those with normal studies and those with minor manometric abnormalities. Further, fundoplication was rare and was actually more common among those with normal manometric findings. Together, our findings would seem to discount the true association between these manometric findings and gastroesophageal reflux.

Long term follow up was available in 98 patients, with at least 5 years between index esophageal manometry and completion of the phone survey. Notably, while only 28% reported clinically significant symptoms at follow up, more than 70% of patients were asymptomatic at follow up. Further, a greater proportion of patients with minor motor abnormalities reported an IDQ score of 0 at follow up than those with normal index esophageal manometry studies. This finding is especially notable as all patients underwent a clinically indicated index manometry study for symptoms, suggesting symptom resolution at follow up in a substantial group of patients. This clinical improvement appeared to be spontaneous, as less than 5% of patients were treated with empiric endoscopic dilation and no patients underwent myotomy, esophagectomy, pneumatic dilation, or botulinum toxin injection. The benign long term outcome of these patients suggests that these findings may represent normal variants, with minimal clinical significance. Alternatively, these manometric findings in symptomatic patients may be thought of as akin to functional disorders, which similarly remit and relapse over time.14

It is important to note that patients with hypertensive peristalsis (nutcracker esophagus) did differ from the other patient groups. Notably, abnormal emptying on esophagram was seen more frequently in this group. However, stasis on conventional barium esophagram has recently been shown to be a poor surrogate for symptomatic dysphagia.15 Our study also found that patients with nutcracker esophagus were more likely to be symptomatic at follow up. However, interpretation of these results needs to be tempered by the small sample size of only 10 patients with hypertensive peristalsis. Nonetheless, unlike other minor manometric abnormalities, physiologic differences in patients with nutcracker esophagus compared to healthy controls have been identified. The existence of diminished compliance, increased muscle thickness, and asynchrony of circular and longitudinal muscle contraction have all been associated with chest pain and heartburn in these patients.16–19 However, it should be noted that the actual relationship of symptoms with nutcracker esophagus is unclear. As seen in our study, a large proportion of patients with nutcracker esophagus are asymptomatic and the persistence or remittance of symptoms is independent of whether manometric evidence of nutcracker esophagus persists in these patients.20,21 Additionally, none of these patients in our cohort required myotomy, pneumatic dilation, botulinum toxin injection, or fundoplication over an extensive follow up period suggesting a benign clinical course.

One potential explanation for the large asymptomatic population at follow-up could be a lack of symptoms at the time of esophageal manometry. Esophageal manometry is often performed in anticipation of fundoplication or to assist in pH probe placement in patients with GERD. It is conceivable that an overrepresentation of such patients in our cohort may explain the lack of symptoms attributable to esophageal transit. However, only 1 patient was identified as having an esophageal manometry performed for the purposes of a planned fundoplication. Further, GERD was the sole indication for manometry in only 73 patients (24%). This group was similar to the remainder of the study cohort. In fact, the manometric findings were normal in 47 (64%), weak peristalsis in 18 (25%), frequent failed peristalsis in 3 (4%), and hypercontractile in 5 (7%). Thus, they were not disproportionately represented in any patient group. Further, while none of these patients had an IDQ score greater than 7, this group only constituted 27 of the 98 patients with follow-up. Additionally, treatment specific to GERD did not appear to influence the lack of symptoms at follow-up. Only 13 of the 27 patients with GERD as the only indication for manometry were on PPI at follow up and only 2 patients had a fundoplication, one of which was still on PPI. Further, it could be argued that the failure to develop symptoms of poor esophageal transit speaks to the benign nature of these manometric findings.

There are several limitations of this study. Structural evaluation of the esophagus utilizing EGD or esophagram was not available in all patients, limiting the ability to correlate manometric findings with these objective measures. In addition, long term follow up was reported in only 33% of patients. This resulted in a relatively small number of patients limiting the strength of conclusions that could be drawn. However, our cohort of 98 patients still represents the most robust report of the natural history of patients with normal studies and minor manometric abnormalities to date. We are aware of only two previous studies assessing the natural history of patients with minor manometric abnormalities identified on esophageal manometry.4,9 In both, conventional rather than high resolution manometry was performed. Additionally, in both studies symptoms were not assessed in a standard fashion. Assessment of symptoms at the time of index manometry was not made in a standardized fashion. Consequently, precise reports on symptom progression or regression for individual patients cannot be made. Our study focused on the clinical significance of findings with a standard approach to high resolution manometry. However, recent work has suggested that modifications such as challenge with solid rather than liquid swallows or repetitive swallows may have important diagnostic value.24,25 Future studies regarding the long-term clinical relevance of these findings are likely needed.

Repeat esophageal manometry was not performed as a part of this study. Thus the evolution of minor manometric findings over time was not assessed. However despite these limitations, our study does demonstrate a benign clinical course for patients with these manometric findings with the dearth of symptoms arguing against an evolution to a major manometric abnormality. Most importantly, these results may allow clinicians to provide patients with reassurance regarding these findings, a fact that is independent of manometric findings at follow up. Finally, since completion of this study an updated Chicago classification version 3 has been published.26 One of the primary changes in this classification is the inclusion of small peristaltic breaks (i.e less than 5cm) as a normal manometric finding. In fact, this change is congruous with our findings as patients with small peristaltic breaks mirrored the demographics, presenting symptoms, and the natural history of those with normal esophageal manometry studies. However, inclusion of these patients among those with minor manometric abnormalities did not appear to affect the overall congruity between patients with normal studies and those with minor manometric abnormalities.

In conclusion, findings from this study suggest that patients with normal and minor esophageal motor function abnormalities become normal or rarely progress over time. Those with minor motor function abnormalities actually appear more likely to be asymptomatic at long term follow up than those with normal studies. Consequently, the identification of normal or minor motor function is likely a positive prognostic indicator and may allow physicians to reassure such patients as these patterns are associated with minimal long term consequences

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01 DK-56033 (to P.J. Kahrilas), R01 DK-079902 (to J.E. Pandolfino), and R01 DK-092217 (to J.E. Pandolfino)

Abbreviations

- HRM

High resolution esophageal manometry

- IDQ

Impact dysphagia questionnaire

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/disclosures: John E. Pandolfino discloses consulting and educational associations with Given Imaging. There are no relevant competing financial and other interests exist for other authors (K. Ravi, L. Friesen, R. Issaka, and P.J. Kahrilas).

Specific Author Contributions: Dr. Ravi is a gastroenterologist in the department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Mayo Clinic Rochester. He assisted in the conduct of the study, the collection of the data, and drafted the manuscript. Dr. Pandolfino is a gastroenterologist in the department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He was instrumental in the design and conduct of the study, data collection, and writing of the manuscript. Dr. Kahrilas is a gastroenterologist in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He assisted in the conduct of the study and the drafting of the manuscript. Laurel Friesen is a research assistant in the department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. She assisted in the collection of the data. Dr. Isakka is a fellow in the department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. She assisted in the conduct of the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bredenoord AJ, et al. Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2012;24(Suppl 1):57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roman S, Lin Z, Kwiatek MA, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Weak peristalsis in esophageal pressure topography: classification and association with Dysphagia. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011;106:349–356. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roman S, et al. Phenotypes and clinical context of hypercontractility in high-resolution esophageal pressure topography (EPT) The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011;107:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Achem SR, Crittenden J, Kolts B, Burton L. Long-term clinical and manometric follow-up of patients with nonspecific esophageal motor disorders. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1992;87:825–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao Y, et al. Lack of correlation between HRM metrics and symptoms during the manometric protocol. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014;109:521–526. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribolsi M, Balestrieri P, Emerenziani S, Guarino MP, Cicala M. Weak peristalsis with large breaks is associated with higher acid exposure and delayed reflux clearance in the supine position in GERD patients. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;109:46–51. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C-LL, Yi C-HH, Liu T-TT. Relevance of ineffective esophageal motility to secondary peristalsis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2014;29:296–300. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinucci I, et al. Esophageal motility abnormalities in gastroesophageal reflux disease. World journal of gastrointestinal pharmacology and therapeutics. 2014;5:86–96. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v5.i2.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naftali T, Levit T, Pomeranz I, Benjaminov FS, Konikoff FM. Nonspecific esophageal motility disorders may be an early stage of a specific disorder, particularly achalasia. Diseases of the esophagus: official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus ISDE. 2008;22:611–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandolfino JE, et al. Classifying esophageal motility by pressure topography characteristics: a study of 400 patients and 75 controls. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007;103:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazarescu A, et al. Perception of dysphagia: lack of correlation with objective measurements of esophageal function. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2010;22:1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fornari F, et al. Relevance of mild ineffective oesophageal motility (IOM) and potential pharmacological reversibility of severe IOM in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2007;26:1345–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim K-YY, et al. Is ineffective esophageal motility associated with gastropharyngeal reflux disease? World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2008;14:6030–6035. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halder SL, et al. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:799–807. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogte A, Bredenoord AJ, Oors J, Siersema PD, Smout AJ. Sensation of stasis is poorly correlated with impaired esophageal bolus transport. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2014;26:538–545. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mujica VR, Mudipalli RS, Rao SSC. Pathophysiology of chest pain in patients with nutcracker esophagus. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2001;96:1371–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dogan I, Puckett JL, Padda BS, Mittal RK. Prevalence of increased esophageal muscle thickness in patients with esophageal symptoms. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;102:137–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung H-YY, et al. Asynchrony between the circular and the longitudinal muscle contraction in patients with nutcracker esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1179–1186. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittal RK, Hong SJ, Bhargava V. Longitudinal muscle dysfunction in achalasia esophagus and its relevance. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility. 2013;19:126–136. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.2.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richter JE, Dalton CB, Bradley LA, Castell DO. Oral nifedipine in the treatment of noncardiac chest pain in patients with the nutcracker esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:21–28. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, Eckert TC, Ferney DM, Griffith LS. Low-dose trazodone for symptomatic patients with esophageal contraction abnormalities. A double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90979-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lufrano R, Heckman MG, Diehl N, Devault KR, Achem SR. Nutcracker esophagus: demographic, clinical features, and esophageal tests in 115 patients. Diseases of the esophagus: official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus/ISDE. 2013 doi: 10.1111/dote.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemme EM, Moraes-Filho JP, Domingues G, Firman CG, Pantoja JA. Manometric findings of esophageal motor disorders in 240 Brazilian patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Diseases of the esophagus: official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus/ISDE. 1999;13:117–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweiss R, Anggiansah A, Wong T, Brady G, Fox M. Assessment of esophageal dysfunction and symptoms during and after a standardized test meal: development and clinical validation of a new methadology utilizing high-resolution manometry. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2014;26:215–218. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoikes N, et al. The value of rapid swallows during preoperative esophageal manometry before laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Surgical Endoscopy. 2012;26:3401–3407. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2350-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roman S, Gyawali CP, Xiao Y, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. The Chicago Classification of motility disorders: an update. Gastrointestinal endoscopy clinics of North America. 2014;24:545–561. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]