Abstract

Aim

To report an analysis of the concept of food insecurity, in order to 1) propose a theoretical model of food insecurity useful to nursing and 2) discuss its implications for nursing practice, nursing research, and health promotion.

Background

Forty eight million Americans are food insecure. As food insecurity is associated with multiple negative health effects, nursing intervention is warranted.

Design

Concept Analysis

Data sources

A literature search was conducted in May 2014 in Scopus and MEDLINE using the exploded term “food insecur*.” No year limit was placed. Government websites and popular media were searched to ensure a full understanding of the concept.

Review Methods

Iterative analysis, using the Walker and Avant method

Results

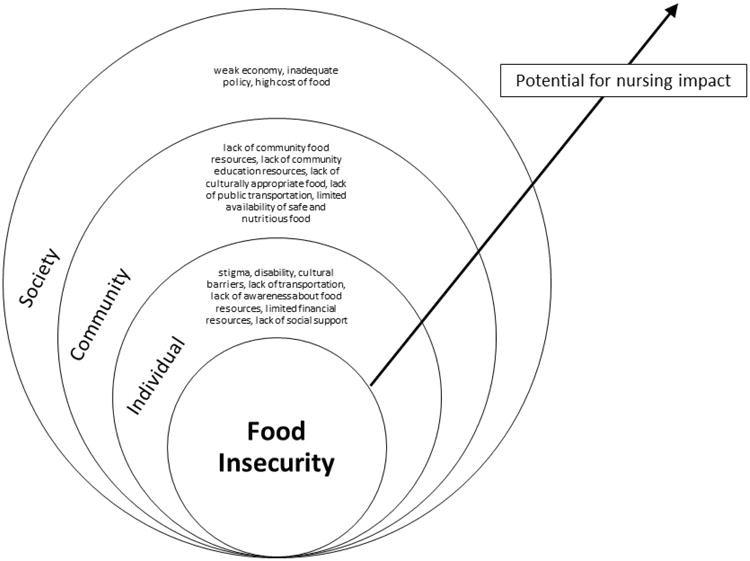

Food insecurity is defined by uncertain ability or inability to procure food, inability to procure enough food, being unable to live a healthy life, and feeling unsatisfied. A proposed theoretical model of food insecurity, adapted from the Socio-Ecological Model, identifies three layers of food insecurity (individual, community, society), with potential for nursing impact at each level.

Conclusion

Nurses must work to fight food insecurity. There exists a potential for nursing impact that is currently unrealized. Nursing impact can be guided by a new conceptual model, Food Insecurity within the Nursing Paradigm.

Keywords: concept analysis, food insecurity, nursing, conceptual model

Concerns about hunger in the United States arose during the Great Depression and intensified in the 1960s during the Johnson administration's Great Society initiative (Kregg-Byers and Schlenk, 2010, Johnson, 1964). Since that time, concern about hunger in America has received increasing attention from both government and the public (Bickel et al., 2000), leading to passage of the “National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990” (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2013). This legislation required a standard metric for identifying and obtaining data on the prevalence of “food insecurity” (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2013). Following passage of the act, the United States Department of Agriculture [USDA] began working towards the creation of a practical way to measure and monitor food insecurity (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2013), with the most recent measurement tool being the Food Security Survey Module (Bickel et al., 2000). Concern about food insecurity continued to grow, with leaders representing academia, private research centers, and federal agencies meeting in 1994 at the National Conference on Food Security Measurement and Research (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2013). Food insecurity remains a focus of government health leaders, with the Institute of Medicine convening a workshop on food insecurity in 2010, looking specifically at its relationship with obesity (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Currently, the USDA Economic Research Service is responsible for routine assessment and measurement of the prevalence of food insecurity.

The USDA defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life” (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2013). Food insecurity is identified by lack of food security. It is currently estimated that 14.5% of American households, or 48,966,000 individuals, are food insecure (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2013). This problem is not unique to America; food insecurity is a global crisis (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2013). This should be of concern to nurses, as individuals living in food insecure households lack access to a healthy diet.

Background

Food insecure Americans eat less nutritious diets than food secure Americans (Champagne et al., 2007; Robaina & Martin, 2013), as low cost foods are often less nutritious (Wallinga, Schoonover, & Muller, 2009). The relationship between food insecurity and poor health persists across the lifespan, impacting infants (Cook et al., 2004), school children, women of childbearing age (Olson, 1999), adults (Stuff et al., 2004), and the elderly (Lee & Frongillo E.A, 2001). Poor nutrition is a risk factor for four of the top ten causes of death in America (Hoyert & Xu, 2012): cancer (Key, Allen, Spencer, & Travis, 2002; Pietinen et al., 1999; Tsugane & Sasazuki, 2007; Voorrips et al., 2000), stroke (Boden-Albala & Sacco, 2000; Fung et al., 2008; Larsson, Åkesson, & Wolk, 2014), cardiovascular disease (Krauss et al., 2000; Mann, 2002), and diabetes (Hu et al., 2001; Mann, 2002; Parillo & Riccardi, 2004). Of concern, food insecurity is also more common in populations known to suffer from health disparities, such as the disabled (Coleman-Jensen and Nord, 2013) and racial/ethnic minorities (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2013).

The negative health effects of food insecurity suggest a need for nursing intervention to help individuals attain optimal health. Although there have been calls for increased nursing involvement (Kregg-Byers and Schlenk, 2010), food insecurity is largely absent from the nursing literature. A stronger nursing voice is needed in the ongoing international discussion about food insecurity and health. To our knowledge, the nursing paradigm lacks an operational definition, conceptual model, or theoretical framework of food insecurity. To address those gaps, utilizing the concept analysis method of Walker and Avant (2005), the purpose of this paper is to 1) explore the meaning of food insecurity, 2) propose a theoretical model of food insecurity relevant to nursing, and 3) discuss its implications for nursing practice, nursing research, and health promotion.

Methods

We utilized the method of Walker and Avant (2011). The steps in this method include 1) determine the aims or purpose of analysis, 2) identify all uses of a concept, 3) determine the defining attributes, 4) construct a model case, 5) construct borderline, related, and contrary cases, 6) identify antecedents and consequences, and 7) define empirical referents. Of note, Walker and Avant note the need for the concept analysis process to be iterative in order to result in a “cleaner, more precise analysis” (Walker and Avant, 2011). Although the steps are presented sequentially, they occurred in a circular manner or, at times, simultaneously.

Data Sources

A literature search was conducted to identify primary research studies relating to food insecurity. Scopus and MEDLINE were searched using the exploded term “food insecur*.” Searches were limited to English language articles relating to food insecurity in the United States. No year limit was placed, as a thorough understanding of the concept and its use over time was desired. In addition, government websites, such as USDA.gov, were searched to inform understanding of the concept. A Google search was also performed to better understand the use of the term in general discourse and popular culture.

Results

The search of MEDLINE and Scopus resulted in 1,492 articles, and 1,480 after removal of duplicates. These were screened by title for relevance to conceptual understanding of food insecurity within the United States. After title screen, 57 articles remained. The 57 articles were further screened first by abstract. Of these, fifteen were deemed relevant and read by full text. A manual search of reference lists and government websites resulted in an additional 24 articles and 9 web documents, resulting in a total of 48 resources.

Uses of the Concept

The use of the concept of food insecurity is relatively consistent throughout the literature. Of the 29 resources that defined food insecurity, 27 used the USDA's definition and two used the United Nations' [UN] definition. Authors of the remaining resources did not specify their use of the concept; they proceed directly to discussion of other aspects of food insecurity, such as antecedents or consequences. Of note, none of the resources identified by the search came from nursing literature or arose from the nursing paradigm.

The USDA defines food insecurity as “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe food or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways” (United States Department of Agrictulture Economic Research Service, 2014b). The USDA's definition attaches key characteristics to this concept. First, it specifies “limited or uncertain availability” of food. Therefore, food insecurity includes having a finite (“limited”) amount of food, as well as lack of guaranteed access (“uncertain availability”). Although these two aspects of the definition are related, the difference is important to note. Food insecurity is not just about quantity of food; it also pertains to certitude of access. The definition is illustrative in its specification of “nutritionally adequate and safe” food. These terms illustrate two different aspects of food security. Safe food is more straightforward and can be considered food that is safe for consumption. For example, safe food is produced under sanitary conditions and is not spoiled. However, nutritionally adequate has a separate meaning. One could argue that having access to endless amount of soda, potato chips, processed sweets, and other nutritionally deplete items may qualify as “nutritionally inadequate,” as it may result in lack of vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, or protein. Therefore, according to this definition, it is possible to have a ubiquitous amount of food and still be food insecure. Furthermore, the USDA's definition qualifies the concept by noting that food insecurity includes obtaining food in socially unacceptable ways. Therefore, if one is able to acquire food, but does so by begging on subway cars, (s)he could be considered food insecure, as the method of obtaining food is not socially acceptable. This relates to the aspect of “limited access,” but adds the qualifier of social norms. Of note, the USDA categorizes food insecurity by level of severity: low and very low (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2013). Households with low food security report “reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet [with] little or no indication of reduced food intake.” Households with very low food security report “multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake” (United States Department of Agrictulture Economic Research Service, 2014a).

The UN, including the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization, utilizes the definition that was determined at the World Food Summit in Rome, Italy in 1996 (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, n.d.): “when all people at all times have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food to maintain a healthy and active life” (World Health Organization, 2014). The WHO literature notes that this issue is linked to health through malnutrition, yet globalization, development, and trade also play key roles in this complex concept (World Health Organization, 2014). The WHO's perspective focuses on problems of distribution and nationwide food security, with special attention paid to agricultural work in developing countries and how current global trends impact those nations' agriculture and food security (World Health Organization, 2014).

Both the USDA and the UN play key roles in tackling food insecurity, guided by their definitions. Although these definitions have similarities, such as their identification of sufficiency of amount, safety, and nutrition, there are significant differences, as they address different problems. The UN focuses on food security issues in developing countries, whereas the United States is considered a developed nation (United Nations, n.d.). Issues of food insecurity present differently in developed versus developing nations (Kregg-Byers and Schlenk, 2010). For example, the severe malnutrition common in certain developing nations, of significant concern to the UN, has been essentially eradicated from the United States (Bickel et al., 2000). Furthermore, the definitions differ in scope, as the USDA focuses attention to a problem that entails only one nation and has the governmental authority to approach the problem more directly through policy change. The UN's approach to food insecurity is necessarily broader, as it deals with diverse nations and is unable to directly establish policy within its member states.

Even though the UN and USDA both define food insecurity, the meanings of global food insecurity and American food insecurity differ significantly. Thus, the role of nurses in addressing global food insecurity versus American food insecurity would differ significantly. A concept analysis of this issue within the nursing paradigm must focus on one of these approaches. This paper concerns itself with food insecurity in the United States, as a representation of food insecurity in developed nations.

Defining Attributes

Defining attributes are those that identify a concept as separate and distinct from related concepts (Walker and Avant, 2011). Four defining attributes of food insecurity emerged from the literature. They include 1) uncertain ability or inability to procure 2) enough food 3) to feel satiated 4) and/or live a healthy life.

Uncertain ability or inability to procure food

The literature demonstrates that the inability to procure food is often due to financial constraints. Findings of several studies suggest a positive association between increasing food prices and increased prevalence of food insecurity (Zhang et al., 2013, Gregory and Coleman-Jensen, 2013). In addition, it is known that poverty is associated with food insecurity (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2013), particularly among households who have limited assets and liquidity constraint (lack sufficient liquid assets and/or have difficulty borrowing) (Chang et al., 2013). However, financial constraints are not the only contributors to procuring food. Researchers have examined non-financial barriers contributing to food insecurity. Ramadurai and colleagues, in their qualitative study of food insecure individuals living in rural Texas, reported that food insecure adults perceived lengthy travel to food stores as a significant barrier to procuring food (Ramadurai et al., 2012). Findings of a cross-sectional study conducted in an urban pediatric clinic suggest that individuals residing in food insecure households were more likely to report transportation as a barrier to procuring food that those in food secure households (Demartini et al., 2013).

Inability to procure enough food

Individuals can have access to food, but when the amount of food is inadequate, they become food insecure. This reflects the episodic nature of food insecurity; households often waver between food insecurity and food security (LeBlanc et al., 2005) based upon food supply. The USDA's food insecurity screening tool also demonstrates that individuals in food insecure households have access to food, yet not in sufficient quantity. The tool assesses reduced food intake, running out of food, and intake of less food than normal (Bickel et al., 2000).

Feeling unsatisfied

The presence of food insecurity is often defined by lack of enough food to feel satisfied. Individuals living in food insecure households do not eat to satiety. For example, in food insecure households, children may express feelings of hunger but parents are unable to adequately respond due to insufficient supply of food in the home (Sano et al., 2011). Food insecure individuals may engage in acts to minimize appetite, such as smoking cigarettes, ignoring mealtimes, or drinking caffeinated beverages (Mammen et al., 2009). The USDA's screening tool for food insecurity also identifies lack of satiety as a key factor, by connecting food insecurity with eating less than desired or not eating enough to satisfy hunger (Bickel et al., 2000).

Unable to live a healthy life

Food insecurity prevents individuals from living a healthy life. For example, food insecure individuals have difficulty affording nutritious diets (Coleman-Jensen, Nord, & Singh, 2013) and experience increased psychological stress (Laraia, Siega-Riz, Gundersen, & Dole, 2006). Poor nutrition and stress increase likelihood of chronic disease (World Health Organization, 2005). Food insecurity also presents significant problems for the chronically ill. For example, Seligman and colleagues reported that low income adults with diabetes are more likely to be hospitalized for hypoglycemia when their Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (food stamps) budget is exhausted and food insecurity worsens (Seligman, Bolger, Guzman, López, & Bibbins-Domingo, 2014). Because food insecure individuals cannot live a healthy life due to poor nutrition and increased stress, food insecurity is associated with many negative health consequences (Olson, 1999, Lee and Frongillo, 2001, Cook et al., 2004, Stuff et al., 2004). For these reasons, inability to live a healthy life may be considered both a defining attruibute and a consequence of food insecurity. Food advocacy organizations and associations of dietary health professionals have recognized this, responding with a call to action to reduce food insecurity (American Dietetic Association, 2010, Feeding America, 2014).

Antecedents

Antecedents are “events or incidents that must occur prior to the occurrence of the concept” (Walker and Avant, 2011). In simplest terms, lack of resources to procure food and lack of access to food are key antecedents. However, antecedents do not occur in a vacuum and may result from diverse contributing factors. For example, food insecurity has been associated with high food costs (Gregory and Coleman-Jensen, 2013, Morrissey et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2013, Ramadurai et al., 2012), lack of access to food stores (Freedman et al., 2013, Ramadurai et al., 2012, Jernigan et al., 2012), a lacking local food environment (i.e. food stores sell unaffordable or undesirable products) (Chang et al., 2013, Demartini et al., 2013), lack of or low income (Chang et al., 2013, Demartini et al., 2013, Anderson, 2013, Langellier et al., 2013), being unable to find culturally appropriate food (Jernigan et al., 2012), low acculturation (Iglesias-Rios et al., 2013), being a first-generation American or immigrant (Langellier et al., 2013), lack of transportation (Demartini el al., 2013, Jernigan et al., 2012), stigma associated with using resources such as federal “food stamps” - the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (Gundersen, 2013, Food Research and Action Center, 2011) or SNAP for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) (Huynh, 2013), lack of awareness about resources such as SNAP (Food Research and Action Center, 2011), inadequate policy to support food insecure individuals (Jernigan et al., 2012), and having a disability (Coleman-Jensen and Nord, 2013).

Consequences

Walker and Avant describe consequences as “events or incident that occur as a result of the occurrence of a concept” (2011). Many negative health consequences may result from food insecurity. Gundersen (2013) provides one of the most through summaries of negative health outcomes. We share findings of his review here, as it is one of the most comprehensive and supports the need to address food insecurity to promote optimal health across the lifespan. Risks begin for the developing fetus, with food insecurity linked to higher rates of birth defects such as spina bifida and anencephaly (Carmichael et al., 2007). In children, risks of food insecurity include anemia (Eicher-Miller et al., 2009, Skalicky et al., 2006), lower nutrient intakes (Cook et al., 2004), greater cognitive problems (Howard, 2011), higher levels of aggression and anxiety (Whitaker et al., 2006), higher probability of being hospitalized (Cook et al., 2006), poorer general health (Cook et al., 2006), higher probability of mental health issues (Alaimo et al., 2002), higher probability of asthma (Kirkpatrick et al., 2010), higher probability of behavioral problems (Huang et al., 2010), and increased oral health problems (Muirhead et al., 2009). In addition, there is a potential connection between food insecurity and childhood obesity, but this relationship is not yet well understood (Dinour, Bergen, & Yeh, 2007; Eisenmann, Gundersen, Lohman, Garasky, & Stewart, 2011; Food Research and Action Center, 2011; Franklin et al., 2012; Larson & Story, 2011). In adults, risks include lower nutrient intakes (Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk, 2008, McIntyre et al., 2003), mental health problems (Heflin et al., 2005) such as depression (Whitaker et al., 2006), physical health problems (Tarasuk, 2001), type 2 diabetes (Seligman et al., 2007), higher levels of chronic disease (Seligman et al., 2010), obesity, particularly in women (Dinour et al., 2007; Food Research and Action Center, 2011; Franklin et al., 2012; Pan, Sherry, Njai, & Blanck, 2012), disordered eating (Kendall, Olson, & Frongillo Jr, 1996), and poorer self-reported health status (Stuff et al., 2004). Food insecure elderly have lower nutrient intakes (Lee and Frongillo, 2001, Ziliak J et al., 2008), increased likelihood of reporting poor or fair health (Lee and Frongillo, 2001, Ziliak J et al., 2008) and having limitations in activities of daily living (Ziliak J et al., 2008).

Case Studies

The following examples demonstrate potential implications of food insecurity for individuals. Consistent with method of Walker and Avant (2011), the model case exemplifies an individual who clearly meets the definition of food insecure, the borderline case includes some but not all of the aspects of the definition, and the contrary case serves as a contrast to this concept.

Model case

AB is a 30 year old Hispanic female living in Washington Heights, New York City. She is a single mother with three school-aged children. She is employed as a retail cashier, but has difficulty paying her bills despite working full-time at minimum wage. After paying her rent, she has little income left for her and her children. She experiences stress due to trying to balance the need to pay for rent and pay for groceries. She receives SNAP benefits, but these funds generally do not last the entire month. In addition, it is difficult for her to get to the grocery store, as the closest full service store is 10 blocks away and she struggles to travel there with three children. As a result, by the last week of the month she sometimes is forced to skip meals to ensure that there is enough food for her children. She worries more on weekends, when her children are unable to participate in free meals programs at school. She reports feeling “starving” by dinnertime, which is when she has her first full meal. She often serves canned soup for dinner, which she waters down to increase the volume, allowing her to use only two cans instead of three. Feeling that she lacks other options, she has considered asking strangers for money on the subway. She is unaware of local food pantries and does not have any local family or friends who can assist her.

Borderline case

CD is a 30 year old Hispanic female living in Washington Heights, New York City. She is a single mother and has an eight month old infant. She left her job as a retail clerk when her child was born, but is able to support herself through a small amount of savings and financial assistance from her large family, who all live nearby. She experiences stress about paying her bills but has always been able to afford essentials such as rent. She purchases groceries on a weekly basis and never goes hungry, though she buys sale items to keep costs low. She worries because her savings are almost exhausted, so she is applying for government nutrition assistance for Women Infants and Children (WIC) with the aid of her local community center. However, she is unsure if she wants to use these benefits, as she has heard others refer to them as “hand-outs” for “lazy people.” In addition, she has been using the local food pantry for rice cereal and baby formula for her child. She worries about being able to afford enough food for her daughter, but her pediatrician says her child is developing normally and is within healthy ranges for height and weight.

Contrary case

EF is a 30 year old Hispanic female living in Washington Heights, New York City. She is married and lives with her husband and two school-age children. Both EF and her husband work at an academic medical center; she is a unit clerk and he is a registered nurse. They share the grocery shopping responsibilities and usually go to the store twice a week. They never worry about their ability to afford groceries. They actively seek out healthier foods to purchase, even if they are more expensive, with the aim of providing nutritious meals for their children. The whole family usually goes to a restaurant approximately two or three times a month.

Interpretation of cases

These cases serve as examples of the multiple factors that impact the development and severity of food insecurity. For example, CD, the borderline case, appears to be food secure because she has assistance from a local community center and family. However, a social issue, the stigma of WIC as a “hand out,” may prevent her from seeking and/or taking advantage of the service she needs. In addition, AB is impacted by the inadequate minimum wage at her job, something that is determined by national and state policy and therefore outside of her direct control.

Empirical referents

Empirical referents are “classes or categories of actual phenomena that by their existence demonstrate occurrence of the concept” (Walker and Avant, 2011). Food insecurity is assessed yearly using the Food Security Survey Module as part of the Current Population Survey (Bickel et al., 2000). Survey responses are analyzed to determine the prevalence of food insecurity. The empirical referents captured in this survey include inadequate amount of food, unaffordability of food, meal skipping and portion cutting, hunger, unplanned weight loss, not eating for a whole day, cutting or skipping children's meals, and hunger related to food affordability (Bickel et al., 2000).

Theoretical implications

Though the role of concept analysis in theory development is debated, there is agreement on the need for the connection between concept analysis and theory (Duncan et al., 2009, Risjord, 2009, Paley, 1996). Our concept analysis has implication for theory development within the nursing paradigm. This analysis informs a theoretical model of food insecurity, arising from an adaptation of the Socio-Ecological Model. The Socio-Ecological Model focuses on the need to change interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy factors in order to promote health (McLeroy et al., 1988). This multilayered approach is advocated in the Institute of Medicine's report on The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century (2003). The report states that population well-being can be realized by “adopting a population health approach that considers the multiple determinants of health” (p. 4). In this spirit, socio-ecological models have been applied to other areas of health concern, such as cancer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013) and violence (World Health Organization, 2002). We propose a similar adaption, by applying the Socio-Ecological Model to food insecurity.

Our model, Food Insecurity within the Nursing Paradigm (Figure 1), reflects the following operational definition: food insecurity is the uncertain ability or inability to procure enough food to feel satiated or meet basic nutritional needs. Arising from this operational definition, we adapt the Socio-Ecological Model to illustrate need for approaches to food insecurity at three levels: societal, community, individual. The arrow illustrates potential for nursing impact at each level.

Figure 1. Food insecurity within the nursing paradigm.

Discussion

Our model suggests multiple opportunities for nursing intervention in fighting food insecurity. Factors at each level are ripe for potential nursing impact. Potential nursing impact is the untapped power of nurses to impact individuals' health in a meaningful and unique way. According to the Institute of Medicine, assuring the health of the public requires a concerted effort across multiple sectors, including academia, the healthcare delivery system, communities, and governmental public health infrastructure (Institute of Medicine, 2003). Nurses contribute to all of these sectors, as the unique nursing role encompasses advocacy, education, care coordination, and clinical care. Each of these provides multiple avenues for potential nursing impact on food insecurity at each level.

At the societal level, nurse scientists can influence policy by creating a body of nursing research around food insecurity, as research can impact policy. For example, further work is needed to clarify the relationship between food insecurity and childhood obesity. Potential mediators of the relationship (hunger, food quality, volatility of access) need to be identified, as different mediators require different policy responses (Institute of Medicine, 2011). In addition, the evidence regarding the relationship between food insecurity and disordered eating is limited, suggesting a need for further research.

At the community level, public health nurses can tackle lack of awareness of food resources. Nurses are often aware of community aid programs and can share this information with individuals who may have inadequate nutrition due to food insecurity. In addition, nurses can include assessment of food insecurity as part of their nutrition counseling (Stevens, 2010), as providers often overlook (Hoisington, 2012) or feel unprepared to screen for food insecurity (Tscholl and Holben, 2006).

At the individual level, staff nurses in bedside care can address patients' lack of financial resources. Patients may confide in the nurse about their concerns about hospitalization costs; these comments suggest a risk for food insecurity. The bedside nurse, as a care coordinator, can facilitate a link with team members, such as social workers or nutritionists, who can help patients plan for food assistance upon discharge. Despite these many opportunities, food insecurity lies largely absent from nursing discourse. The unique contribution of nursing has not yet been widely harnessed in addressing food insecurity. This paper provides a call to do so, with guidance from the model and operational definition that emerged from this concept analysis.

Limitations

This analysis presents certain limitations. It is possible that relevant articles may not have been identified as only two databases were searched. Exclusion of articles in languages other than English may also have limited the literature available for review. In addition, primary sources, such as interviews, were not available to inform this concept analysis.

Conclusions and Implications for Nursing Practice

A thoughtful analysis of food insecurity takes the first step towards its resolution. The model of Food Insecurity within the Nursing Paradigm (Figure 1) demonstrates multiple areas for potential nursing impact. Practical applications in these areas need to be developed through nursing practice and research. With a fuller understanding of this concept, nurses can turn their attention to addressing this issue from the unique nursing perspective. Nursing intervention in food insecurity has the potential to lead to improved nutrition, resulting in improved health.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Gross Cohn, PhD, RN, for her assistance in developing an earlier draft of this manuscript.

This publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Nursing Research through Grant Number T32 NR014205 and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through Grant Number UL1 TR000040. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).

Contributor Information

Krista Schroeder, Columbia University School of Nursing.

Arlene Smaldone, Assistant Dean of Scholarship and Research, Columbia University School of Nursing.

References

- Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Family food insufficiency, but not low family income, is positively associated with dysthymia and suicide symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132:719–725. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: food insecurity in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010;110:1368–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MD. Beyond food security to realizing food rights in the US. Journal of Rural Studies. 2013;29:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. RE: Guide to Measuring Household Food Security 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael SL, Yang W, Herring A, Abrams B, Shaw GM. Maternal food insecurity is associated with increased risk of certain birth defects. Journal of Nutrition. 2007;137:2087–2092. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.9.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social ecological model. 2013 [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/crccp/sem.htm.

- Chang Y, Chatterjee S, Kim J. Household Finance and Food Insecurity. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2013:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M. Economic Research Report. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service; 2013. Food Insecurity Among Households With Working-Age Adults With Disabilities. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M, Singh A. Household food security in the United States 2012. 2013 Retrieved from http://162.79.45.209/media/1183208/err-155.pdf.

- Cook JT, Frank DA, Berkowitz C, Black MM, Casey PH, Cutts DB, Meyers AF, Zaldivar N, Skalicky A, Levenson S, Heeren T, Nord M. Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134:1432–1438. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.##. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JT, Frank DA, Levenson SM, Neault NB, Heeren TC, Black MM, Berkowitz C, Casey PH, Meyers AF, Cutts DB, Chilton M. Child food insecurity increases risks posed by household food insecurity to young children's health. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136:1073–1076. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.4.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demartini TL, Beck AF, Kahn RS, Klein MD. Food insecure families: Description of access and barriers to food from one pediatric primary care center. Journal of Community Health. 2013;38:1182–1187. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinour LM, Bergen D, Yeh MC. The Food Insecurity–Obesity Paradox: A Review of the Literature and the Role Food Stamps May Play. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107(11):1952–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C, Cloutier JD, Bailey PH. In response to: Risjord M. (2009) Rethinking concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 65(3), 684-691. Journal of advanced nursing. 2009;65:1985–1986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05076.x. author reply 1987-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher-Miller HA, Mason AC, Weaver CM, Mccabe GP, Boushey CJ. Food insecurity is associated with iron deficiency anemia in US adolescents. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;90:1358–1371. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann JC, Gundersen C, Lohman BJ, Garasky S, Stewart SD. Is food insecurity related to overweight and obesity in children and adolescents? A summary of studies, 1995-2009. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(501):e73–e83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeding America. Physical and Mental Health. 2014 [Online]. Available: http://feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/impact-of-hunger/physical-and-mental-health.aspx#.

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. The state of food insecurity in the world 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. World food summit n.d. [Google Scholar]

- Food Research and Action Center. Food insecurity and obesity: Understanding the connections 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Food Research and Action Center. SNAP access in urban America: A city-by-city snapshot 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin B, Jones A, Love D, Puckett S, Macklin J, White-Means S. Exploring mediators of food insecurity and obesity: A review of recent literature. Journal of Community Health. 2012;37(1):253–264. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9420-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DA, Blake CE, Liese AD. Developing a Multicomponent Model of Nutritious Food Access and Related Implications for Community and Policy Practice. Journal of Community Practice. 2013;21:379–409. doi: 10.1080/10705422.2013.842197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory CA, Coleman-Jensen A. Do high food prices increase food insecurity in the united states? Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 2013;35:679–707. [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen C. Food insecurity is an ongoing national concern. Advances in Nutrition. 2013;4:36–41. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha WC, Oh SJ, Kim JH, Lee JM, Chang SA, Sohn TS, Son HS. Severe hypoglycemia is a serious complication and becoming an economic burden in diabetes. Diabetes and Metabolism Journal. 2012;36(4):280–284. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.4.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflin CM, Siefert K, Williams DR. Food insufficiency and women's mental health: Findings from a 3-year panel of welfare recipients. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:1971–1982. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoisington AT. Health care providers' attention to food insecurity in households with children. Preventive medicine. 2012;55:219. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard LL. Does food insecurity at home affect non-cognitive performance at school? A longitudinal analysis of elementary student classroom behavior. Economics of Education Review. 2011;30:157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Oshima KMM, Kim Y. Does food insecurity affect parental characteristics and child behavior? Testing mediation effects. Social Service Review. 2010;84:381–401. doi: 10.1086/655821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh D. Women, infants, and children (WIC): Experience, awareness, access. Wilder Research 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Rios L, Bromberg JE, Moser RP, Augustson EM. Food Insecurity, Cigarette Smoking, and Acculturation Among Latinos: Data From NHANES 1999-2008. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9957-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy LM, Miller EA, Olson S, editors. Institute of Medicine. Hunger and Obesity: Understanding a Food Insecurity Paradigm: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Troy LM, Miller EA, Olson S, editors. Institute of Medicine. Hunger and Obesity: Understanding a Food Insecurity Paradigm: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VBB, Salvatore AL, Styne DM, Winkleby M. Addressing food insecurity in a Native American reservation using community-based participatory research. Health Education Research. 2012;27:645–655. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LB. Proclamation 3606 - National Freedom From Hunger Week, 1964. 1964 [Online]. Available: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=75219.

- Kendall A, Olson CM, Frongillo EA., Jr Relationship of hunger and food insecurity to food availability and consumption. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1996;96(10):1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick SI, Mcintyre L, Potestio ML. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:754–762. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Nutrient Inadequacies among Canadian Adults and Adolescents. The Journal of Nutrition. 2008;138:604–612. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.3.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kregg-Byers CM, Schlenk EA. Implications of food insecurity on global health policy and nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2010;42:278–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langellier BA, Chaparro MP, Sharp M, Birnbach K, Brown ER, Harrison GG. Trends and Determinants of Food Insecurity Among Adults in Low-Income Households in California. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition. 2013;7:401–413. [Google Scholar]

- Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Gundersen C, Dole N. Psychosocial factors and socioeconomic indicators are associated with household food insecurity among pregnant women. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(1):177–182. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Story MT. Food insecurity and weight status among U.S. children and families: A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40(2):166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc M, Kuhn B, Blaylock J. Poverty amidst plenty: Food insecurity in the United States. Agricultural Economics. 2005;32:159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Frongillo EAJ. Nutritional and health consequences are associated with food insecurity among U.S. Elderly persons. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131:1503–1509. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammen S, Bauer JW, Richards L. Understanding persistent food insecurity: A paradox of place and circumstance. Social Indicators Research. 2009;92:151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mcintyre L, Glanville NT, Raine KD, Dayle JB, Anderson B, Battaglia N. Do low-income lone mothers compromise their nutrition to feed their children? CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;168:686–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcleroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education & Behavior. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey TW, Jacknowitz A, Vinopal K. Local food prices and their associations with children's weight and food security. Pediatrics. 2014;133:422–430. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead V, Quiñonez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Oral health disparities and food insecurity in working poor Canadians. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2009;37:294–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson CM. Nutrition and health outcomes associated with food insecurity and hunger. Journal of Nutrition. 1999;129:521S–524S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.521S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paley J. How not to clarify concepts in nursing. Journal of advanced nursing. 1996;24:572–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.22618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Sherry B, Njai R, Blanck HM. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Obesity among US Adults in 12 States. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112(9):1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadurai V, Sharf BF, Sharkey JR. Rural Food Insecurity in the United States as an Overlooked Site of Struggle in Health Communication. Health Communication. 2012;27:794–805. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.647620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risjord M. Rethinking concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65:684–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano Y, Garasky S, Greder KA, Cook CC, Browder DE. Understanding Food Insecurity Among Latino Immigrant Families in Rural America. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2011;32:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya AM, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: Results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2002. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:1018–1023. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income nhanes participants. Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140:304–310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalicky A, Meyers AF, Adams WG, Yang Z, Cook JT, Frank DA. Child Food Insecurity and Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Low-Income Infants and Toddlers in the United States. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2006:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CA. Exploring Food Insecurity Among Young Mothers (15–24 Years) Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2010;15:163–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2010.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuff JE, Casey PH, Szeto KL, Gossett JM, Robbins JM, Simpson PM, Connell C, Boglet ML. Household food insecurity is associated with adult health status. Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134:2330–2335. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk VS. Household food insecurity with hunger is associated with women's food intakes, health and household circumstances. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131:2670–2676. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tscholl E, Holben DH. Knowledge and practices of Ohio nurse practitioners regarding food access of patients. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2006;18:335–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Statistical annex: Country classification. n.d. [Online]. Available: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_current/2012country_class.pdf.

- United States Department of Agrictulture Economic Research Service. Definitions of food security. 2014a [Online]. Available: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx#ranges.

- United States Department of Agrictulture Economic Research Service. Food security in the US: Measurement. 2014b [Online]. Available: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx#.U5nWcoWJuDk.

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Food security in the US: History and background. 2013 [Online]. Available: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/history-background.aspx#.UwPHj7SxFsJ.

- Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. Prentice Hall; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker RC, Phillips SM, Orzol SM. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e859–e868. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Chronic Diseases and thier Common Risk Factors. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Food security. 2014 [Online]. Available: http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story028/en/

- Zhang Q, Jones S, Ruhm CJ, Andrews M. Higher food prices may threaten food security status among American low-income households with children. Journal of Nutrition. 2013;143:1659–1665. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.170506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziliak J, Gundersen C, M H. The causes, consequences, and future of senior hunger in America 2008 [Google Scholar]