Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen whose survival in food processing environments may be associated with its tolerance to desiccation. To probe the molecular mechanisms used by this bacterium to adapt to desiccation stress, a transposon library of 11,700 L. monocytogenes mutants was screened, using a microplate assay, for strains displaying increased or decreased desiccation survival (43% relative humidity, 15°C) in tryptic soy broth (TSB). The desiccation phenotypes of selected mutants were subsequently assessed on food-grade stainless steel (SS) coupons in TSB plus 1% glucose (TSB-glu). Single transposon insertions in mutants exhibiting a change in desiccation survival of >0.5 log CFU/cm2 relative to that of the wild type were determined by sequencing arbitrary PCR products. Strain morphology, motility, and osmotic stress survival (in TSB-glu plus 20% NaCl) were also analyzed. The initial screen selected 129 desiccation-sensitive (DS) and 61 desiccation-tolerant (DT) mutants, out of which secondary screening on SS confirmed 15 DT and 15 DS mutants. Among the DT mutants, seven immotile and flagellum-less strains contained transposons in genes involved in flagellum biosynthesis (fliP, flhB, flgD, flgL) and motor control (motB, fliM, fliY), while others harbored transposons in genes involved in membrane lipid biosynthesis, energy production, potassium uptake, and virulence. The genes that were interrupted in the 15 DS mutants included those involved in energy production, membrane transport, protein metabolism, lipid biosynthesis, oxidative damage control, and putative virulence. Five DT and 14 DS mutants also demonstrated similar significantly (P < 0.05) different survival relative to that of the wild type when exposed to osmotic stress, demonstrating that some genes likely have similar roles in allowing the organism to survive the two water stresses.

INTRODUCTION

The foodborne bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes continues to be a significant issue in the food supply chain, causing repeated recalls and outbreaks of foodborne illness. L. monocytogenes is ubiquitous in nature but is transmitted to humans predominantly through contaminated food, with the majority of listeriosis outbreaks being associated with ready-to-eat (RTE) products, such as deli meats, soft cheeses, and fresh produce (1, 2). Listeriosis is a very serious disease with mortality rates of 20 to 40% (3). Populations which are more susceptible to listeriosis include the elderly, pregnant women, newborns, and immunocompromised individuals.

Several foodborne outbreaks of listeriosis have been traced back to the processing facilities in which the products were made (4–8). Recent literature also suggests that contamination at the retail level may be a significant cause of listeriosis (9–11). In both environments, L. monocytogenes has been isolated from food contact surfaces and non-food contact surfaces, such as floors and drains (12). Once introduced into a processing environment, L. monocytogenes can persist for years, despite the harsh environmental conditions that it encounters during food processing, preservation, and plant sanitation efforts (13). The persistence of L. monocytogenes in the food supply chain has most commonly been attributed to its ability to adapt to refrigeration temperatures and high-acid and high-salt environments (14, 15). Additionally, many strains are capable of adhering to and subsequently forming biofilms on a variety of abiotic surfaces, further enhancing the resistance of cells to sanitizers and dehydration. Recently, it was shown that L. monocytogenes can survive desiccation for 3 months on stainless steel (SS) surfaces in a simulated food processing environment (16), demonstrating that desiccation tolerance also plays a significant role in the bacterium's ability to persist.

Previous studies found that the survival of L. monocytogenes on food-grade stainless steel surfaces was enhanced by environmental factors and mechanisms, such as osmoadaptation prior to desiccation; desiccation in the presence of 5% NaCl, food residues, and lipids; and the formation of a mature biofilm (16–19). However, the genetic factors and mechanisms used by this bacterium to adapt to desiccation stress still remain largely understudied. Some hypotheses can be derived from literature describing the response of other cells (microbe, plant, or animal) to desiccation stress, as the fundamental principles of dehydration damage at the molecular level (i.e., proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleotides) are similar. Cellular dehydration causes solutes to concentrate within the cell, thereby imparting both osmotic and oxidative stresses (20). When the aqueous monolayer surrounding macromolecules is removed, fundamental cellular machinery, such as ribosomes, enzymes, transport systems, and important metabolic pathways, may become impaired (21). Correspondingly, transcriptome studies on Gram-negative bacteria subjected to desiccation stress, specifically, Salmonella (22, 23) and Pseudomonas spp. (24, 25), identified the upregulation of genes involved in lipid and amino acid biosynthesis, DNA repair, potassium ion transport, and osmolyte uptake, among others.

The goal of the present study was to elucidate novel genetic factors contributing to desiccation tolerance in L. monocytogenes. This was accomplished by constructing a library of L. monocytogenes mutants with random Himar1 transposon insertional mutations in a serotype 1/2a food isolate. The library was then screened for mutants displaying increased or decreased desiccation tolerance on stainless steel surfaces compared to the desiccation tolerance of the wild type (WT). Our results demonstrate that the desiccation tolerance of L. monocytogenes is a complex process involving a wide variety of genes. Ultimately, 30 desiccation-associated loci were identified in this study, and some of these correspond to those found previously in other bacteria and others represent loci newly recognized to be involved in desiccation tolerance. We also report that 19 of these genes likely have a role in adaptation to severe osmotic stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

Insertional mutagenesis was performed in L. monocytogenes 568, which is a serotype 1/2a food isolate (26). All reagents and antibiotics used in this study were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Whitby, Ontario, Canada) and Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada), respectively. Unless otherwise stated, when necessary, medium was supplemented with 10 μg/ml erythromycin (Erm) and/or kanamycin (Kan). Routine culturing was carried out on brain heart infusion (BHI; Difco) agar (15% [wt/wt] technical agar; Difco) or in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco). All bacterial stocks were stored at −80°C in BHI broth supplemented with 20% glycerol.

Generation of transposon library.

Insertional mutagenesis was carried out using the shuttle vector pMC39 (kindly obtained from the H. Marquis Laboratory, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA), which contains a temperature-sensitive origin of replication and the Himar1 mariner transposon (27). The pMC39 plasmid was electroporated into competent L. monocytogenes 568 cells prepared as described by Alexander et al. (28), using 0.1-cm cuvettes in a Micropulser electroporator (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) set to a field strength of 1.0 kV. Following electroporation, the cells were resuspended in 1.0 ml of SOC medium (2% tryptone [Oxoid], 0.5% yeast extract [Oxoid], 10 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MgSO4 [Mallinckrodt], 20 mM glucose) and allowed to recover for 3 h at 28°C under static conditions.

Transposon mutagenesis was performed following a previously described protocol (29). L. monocytogenes 568 transformants were selected at 30°C on BHI agar-Erm (5 μg/ml). Individual colonies were then inoculated and grown overnight in BHI agar-Erm plus Kan at 30°C with shaking. The cultures were diluted 1/200 in BHI agar-Erm, grown for 1 h at 30°C with shaking, and then shifted to 40°C for approximately 6 h until the A600 was 0.3 to 0.5 (NanoPhotometer P330; Implen, Westlake Village, CA, USA). Aliquots of the culture were spread plated on BHI agar-Erm and incubated at 40°C for 2 days. Approximately 11,700 mutant colonies were inoculated into polystyrene microtiter plates (96-well plates; Costar) containing 100 μl of TSB and 100 μl of 30% (wt/wt) glycerol in distilled water (dH2O) and grown for 2 days at room temperature (∼22°C), before being stored at −80°C until further use. Plasmid retention was determined to be less than 2.5%, and 25 mutants were examined to confirm random insertion of the transposon in the L. monocytogenes 568 chromosome.

Screening the transposon library for DT and DS mutants.

L. monocytogenes 568 transposon insertion mutants were subjected to a two-stage screening process to identify genes contributing to increased or decreased tolerance to desiccation stress. Frozen library stocks were thawed at room temperature, and 10 μl from each well was used to inoculate 190 μl of fresh TSB distributed in microtiter plates. The plates were incubated overnight at room temperature, and final readings of the absorbance at 490 nm were recorded using a BioTek* ELx808* absorbance microplate reader (Fisher Scientific) connected to a computer operating Gen5 (version 2.0) reader control software (BioTek, Fisher Scientific).

To determine the growth kinetics of the mutants, 10 μl from each well of the overnight cultures was inoculated into microtiter plates containing 190 μl of fresh TSB, and the plates were incubated at 15°C. The absorbance at 490 nm of each well was recorded every 3 h until all mutants reached stationary phase (approximately 20 h).

To isolate mutants with an altered desiccation phenotype, 10 μl from the overnight culture plates was spotted on the bottom of empty microtiter plates, and the plates were placed in desiccators preconditioned to 43% relative humidity (RH; using saturated K2CO3) and 15°C as previously described (17). After 5 days of desiccation, the growth in each well, representing one unique transposon mutant, was rehydrated with 190 μl of TSB, and the plates were incubated at 15°C under static conditions. The plates were briefly shaken every 3 h, and the A490 was recorded until stationary phase was achieved by the majority of isolates (approximately 28 h). The resulting rehydration growth curves were used to select mutants for the second screening procedure. The premise of this assay was that desiccation-tolerant (DT) and desiccation-sensitive (DS) mutants would show faster and slower regrowth after desiccation, respectively, than the WT. The resulting curves were visually assessed, and mutants were categorized as DT if they displayed short lag phases and reached an A490 of 0.40 more than 2 h before the majority of mutants. Conversely, DS mutants were selected on the basis of displaying long lag phases that resulted in mutants achieving an A490 of 0.10 more than 2 h after the majority of isolates and the WT. DS mutants were discarded if they displayed low growth rates under regular conditions at 15°C.

Quantitative determination of desiccation survival on stainless steel coupons.

In total, 190 mutants were selected from the first screening procedure and streaked out on BHI agar-Erm and BHI agar-Kan to confirm the presence of the transposon and the absence of the pMC39 plasmid, respectively. From the BHI agar-Erm plates, colonies were inoculated into 5 ml of TSB supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) glucose (TSB-glu) and incubated at 15°C for 48 h. Following incubation, the cultures were centrifuged, resuspended in fresh TSB-glu to an A450 of 1, and diluted to obtain a cell density of 7.5 log CFU/cm2 when spotted onto sterile food-grade SS (314 finish) coupons (0.5 by 0.5 cm). The inoculated coupons were desiccated (43% RH, 15°C) for 7 days. Three coupons were prepared for each mutant per sampling day (days 0, 1, 2, 4, and 7), and survivors were released from the coupons by sonication and vortexing (17), followed by enumeration via the plate count method on BHI agar. Mutants which exhibited a >0.5-log-CFU/cm2 increase or decrease in survival relative to that of the WT during the 7-day desiccation period were selected for arbitrary PCR and DNA sequencing.

Arbitrary PCR.

To determine the affected genes in the desiccation mutants, the arbitrary primer PCR method (27, 29) was used to determine the nucleotide sequences flanking the transposon insertion sites. This method uses two sequential PCRs to amplify the transposon-chromosome junctions.

The first arbitrary PCR was performed using an IDTaq DNA polymerase kit (ID Labs Manufacturing Inc., London, ON, Canada). Each 24.5-μl reaction mixture contained 2.5 μl 10× MgCl2-free buffer, 0.5 μl deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture (2.5 mM each), 2.0 μl MgCl2, 0.25 μl ID Labs Taq polymerase, 18.25 μl RNA-free dH2O, 0.5 μl of each primer stock (10 μM; see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and one mutant colony from BHI agar-Erm plates. The following PCR cycle was conducted using a Tgradient thermocycler (Whatman Biometra, Goettingen, Germany) and consisted of a 5-min initial denaturation step at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 34°C for 45 s, and elongation at 72°C for 1 min. This was followed by a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. The resulting PCR products were then diluted by adding 0.5 μl to 24.5 μl of RNA-free dH2O. The second PCR used 5 μl 5× buffer, 0.5 μl high-fidelity Taq DNA polymerase (HotStar Taq DNA polymerase; Qiagen, Toronto, ON, Canada), 2.5 μl of each primer stock (10 μM; see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and 14 μl RNA-free dH2O for a total of 25 μl, including 0.5 μl of the diluted products from round I. The PCR cycle was as follows: a 5-min initial denaturation step at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 34°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The final extension step was at 72°C for 10 min. Gel electrophoresis in an agarose gel (1.5% agarose, 1% TAE [Tris-acetate-EDTA]) was used to confirm the presence of amplicons prior to sequencing.

Identification of transposon insertion sites.

Purification of the products obtained by the arbitrary PCR method was performed using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) as directed by the manufacturer. Purified samples were diluted in pH-adjusted dH2O (pH 7.0 to 8.5) to concentrations of 1 to 10 ng/μl and sequenced by the Sanger method (McGill University and Génome Québec, Montréal, Québec, Canada). Sequences were aligned to the complete genome sequence of L. monocytogenes strain EGD-e (GenBank accession number NC_003210) (30) using BLASTn online software (National Center for Biotechnology Information; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Where the functions of some genes were not annotated in EDG-e, BLASTn searches were conducted on other L. monocytogenes 1/2a serotype genomes. Sequencing gaps and absences were closed in using additional primers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Osmotic stress survival.

Sequenced desiccation mutants were tested for survival during severe osmotic stress exposure. Colonies from BHI agar-Erm plates were precultured in 5 ml TSB-glu for 2 days at 15°C, centrifuged, resuspended in TSB-glu containing 20% (wt/wt) NaCl (water activity, ∼0.86) to a final concentration of 7.5 log CFU/ml, and incubated at 15°C for 49 h. Survivors were regularly enumerated in triplicate by plating on BHI agar.

Motility assay and staining of flagella.

Insertion of the transposon affected genes involved in flagellum biosynthesis and motility in seven DT mutants. To elucidate any possible causal relationship between impaired motility and desiccation tolerance, the motility of all mutants with respect to that of the WT was assessed at 15°C. To accomplish this, colonies from BHI agar plates (grown at 20°C for 48 h) were stabbed in triplicate into petri dishes containing soft BHI agar (0.3%, wt/wt) and incubated for 72 h at 15°C. A large area of bacterial growth surrounding the initial point of inoculation was indicative of bacterial motility. The presence or absence of flagella in seven mutants immotile at 15°C was determined using a crystal violet-based method (110) with the WT serving as a control. Prior to staining, cells were grown for 2 days at 20°C on BHI agar. Stained slides were examined under ×1,000 magnification with a Nikon Eclipse 80i light microscope (Nikon Canada, Mississauga, ON, Canada).

Endpoint RT-PCR to determine the expression of selected flagellum-associated genes.

L. monocytogenes 568 and motility mutants were grown statically in TSB-glu at 15°C until they reached an A450 of ∼0.8. One volume of each bacterial culture was added to 2 volumes of RNA stabilizer (RNAprotect bacterial reagent; catalog number 76506; Qiagen). RNA was extracted (RNeasy minikit; Qiagen) after pretreatment of the cells with 20 mg/ml lysozyme (Roche, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and 20 μg/ml proteinase K (Roche) for 15 min at 37°C. Genomic DNA (gDNA) wipeout buffer (Qiagen) was used for 2 min at 42°C to eliminate gDNA. RNA was then converted to cDNA (QuantiTect reverse transcriptase [RT] kit; Qiagen), with the reverse transcriptase reaction mixture being incubated at 42°C for 25 min, followed by quenching at 95°C for 3 min.

PCR was performed on the cDNA using primers (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) designed to amplify (150 to 200 bp) the affected or adjacent downstream gene in each of the seven motility mutants. The primers were first confirmed to work on gDNA. For each gene, after gDNA removal sample RNA was used as the negative control, while RT-PCR using primers specific for 16S rRNA and flaA (i.e., a motility gene not impacted in any of the mutants) served as the positive control. Each PCR (25 μl) was performed using a PCR mixture consisting of 1.5 μl of 25 mM Mg2+, 12.5 μl of OneTaq Hot Start 2× master mix (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA), 0.5 μl of each 10 μM primer, 9 μl H2O, and 1 μl of a 1/10-diluted cDNA mixture or an equivalent amount of RNA following gDNA removal. The temperature conditions for the PCR were 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 45 s (54°C for 16S rRNA), and 72°C for 60 s and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

Heat tolerance assay.

Mutant DT10 contained the transposon insertion in the butyrate kinase gene (lmo1370, buk), whose interruption was previously reported to produce a heat-resistant mutant of L. monocytogenes 568 (31). To determine if DT10 also exhibited this phenotype, its survival during a mild heat treatment was compared to that of the WT. Cells were first cultured in TSB-glu for 2 days at 15°C and then centrifuged and resuspended in peptone saline (PS; 0.1% peptone, 0.85% NaCl) to a concentration of 7.5 log CFU/ml. Aliquots of 110 μl were distributed in PCR tubes and heated to 55°C in a thermocycler (Tgradient; Whatman Biometra) for 30 min. Treated samples (n = 3) were serially diluted in PS, and survivors were enumerated on BHI agar.

Statistical analysis.

The desiccation and osmotic stress survival of the mutants was statistically compared to that of the WT using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Dunnett's post hoc test in IBM SSPS statistics software. Differences were concluded to be significant when P was ≤0.05.

RESULTS

Discovery of DT and DS mutants.

Screening of 11,700 transposon insertion mutants for desiccation survival in a microplate assay resulted in the detection of 129 desiccation-sensitive (DS) and 61 desiccation-tolerant (DT) candidates. Secondary screening of these mutants on food-grade SS coupons yielded 15 DT and 15 DS mutants, each with a >0.5-log-CFU/cm2 increase or decrease in survival, respectively, compared to that of the WT during the 7-day desiccation trial.

After 24 h of desiccation on the SS surface, 14 DT mutants displayed significantly (P < 0.05) increased survival compared to that of the WT, and 9 of these maintained significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced survival after 7 days (Table 1). Four mutants (DT02, DT06, DT10, DT11) exhibited a final mean log reduction of <1 log CFU/cm2, with the two most tolerant mutants (DT10 and DT11) displaying <0.20-log-CFU/cm2 reductions in survival, whereas that for the WT was 1.72 log CFU/cm2 (Table 1). While all other DT and DS mutants had growth rates similar to the growth rate of the WT, both DT10 and DT11 displayed reduced growth rates in TSB-glu at 15°C. The reduced growth rates of these mutants were masked in the initial microtiter plate rehydration assay due to the minimal viability loss after 5 days of desiccation. Unlike the other mutants, which reached stationary phase (A450, >1.20) during preculturing (2 days, 15°C), DT10 and DT11 reached only late exponential phase (A450, ∼0.60) before being harvested, resuspended, and inoculated (7.5 log CFU/cm2) onto the SS coupons. Interestingly, after 4 days of desiccation on SS coupons, DT11 colonies on BHI agar took on a crateriform donut-shaped morphology (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Transposon insertion sites identified in Listeria monocytogenes DT mutants mapped to the complete EGD-e sequenced genome and the corresponding losses in viability observed during desiccation and exposure to severe osmotic stressa

| L. monocytogenes strain | Gene locus tag | Gene name | Function | Survival reduction (mean ± SD Δlog CFU/cm2 [desiccation] or Δlog CFU/ml [osmotic stress]) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desiccation |

Osmotic stress at 49 h | |||||||

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 7 | |||||

| 568 | −1.48 ± 0.14 | −1.52 ± 0.12 | −1.74 ± 0.03 | −1.72 ± 0.15 | −0.74 ± 0.17b | |||

| DT01 | lmo0289 | yycH | TCS regulatory proteinc | −0.67 ± 0.09d | −0.87 ± 0.05d | −1.20 ± 0.25e | −1.33 ± 0.28 | −0.53 ± 0.14b |

| DT02 | lmo0676 | fliP | Flagellar biosynthesis protein | −0.49 ± 0.26f | −0.54 ± 0.11f | −0.71 ± 0.19f | −0.91 ± 0.23d | −0.22 ± 0.16f |

| DT03 | lmo0679 | flhB | Flagellar biosynthesis protein | −0.75 ± 0.23d | −0.80 ± 0.20f | −1.03 ± 0.45e | −1.51 ± 0.53 | −0.10 ± 0.09b,f |

| DT04 | lmo0686 | motB | Chemotaxis flagellar motor rotation protein | −0.97 ± 0.03e | −0.79 ± 0.17f | −1.47 ± 0.36 | −1.20 ± 0.04 | −1.13 ± 0.10d,g |

| DT05 | lmo0696 | flgD | Flagellar basal body rod modification protein | −1.12 ± 0.14 | −1.40 ± 0.09 | −1.28 ± 0.30 | −1.16 ± 0.24e | −1.00 ± 0.10b |

| DT06 | lmo0699 | fliM | Flagellar motor switch protein | −0.89 ± 0.16e | −1.06 ± 0.15e | −0.97 ± 0.18d | −0.91 ± 0.14d | −1.07 ± 0.14d |

| DT07 | lmo0700 | fliY | Flagellar motor switch protein | −0.87 ± 0.27e | −0.96 ± 0.05d | −1.20 ± 0.15e | −1.44 ± 0.19 | −0.72 ± 0.05 |

| DT08 | lmo0706 | flgL | Flagellar hook-associated protein | −0.99 ± 0.40e | −0.83 ± 0.36f | −1.30 ± 0.55 | −1.26 ± 0.31 | −0.14 ± 0.02f |

| DT09 | lmo0771 | ATP-sensitive inward rectifier potassium channel 15h | −0.74 ± 0.26d | −1.07 ± 0.27e | −1.05 ± 0.14d | −1.18 ± 0.02e | −0.47 ± 0.10b | |

| DT10 | lmo1370 | buk | Butyrate kinase | −0.01 ± 0.09f | −0.05 ± 0.11f | −0.10 ± 0.05f | −0.10 ± 0.19f | −0.41 ± 0.15e,g |

| DT11 | lmo1371 | lpd | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | −0.05 ± 0.07f | −0.14 ± 0.20f | −0.09 ± 0.04f | −0.19 ± 0.13f | −0.51 ± 0.04g |

| DT12 | lmo1582 | Adenine-specific DNA methylase | −0.83 ± 0.29d | −0.91 ± 0.23d | −1.20 ± 0.07e | −1.26 ± 0.26 | −0.70 ± 0.09 | |

| DT13 | lmo1742 | adeC | Adenine deaminase | −0.70 ± 0.12d | −0.73 ± 0.21f | −0.95 ± 0.08d | −1.10 ± 0.17e | −0.66 ± 0.12 |

| DT14 | lmo1744 | NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase | −0.66 ± 0.26f | −0.29 ± 0.04f | −0.72 ± 0.16f | −1.11 ± 0.10e | −0.39 ± 0.07e | |

| DT15 | lmo1786 | inlC | Internalin C | −0.55 ± 0.32f | −0.41 ± 0.08f | −0.64 ± 0.12f | −1.12 ± 0.33e | −0.64 ± 0.12g |

Cells were desiccated for 7 days at 43% RH and 15°C in TSB plus 1% glucose on SS coupons at an initial concentration of 7.5 log CFU/cm2. Osmotic stress survival was determined by resuspending TSB-glu-grown cultures to 7.5 log CFU/ml in TSB-glu plus 20% NaCl for 49 h at 15°C (n = 3). The complete L. monocytogenes EGD-e sequenced genome can be found in GenBank under accession number NC_003210.

Significantly (P < 0.05) higher survival during osmotic (49 h) stress than during desiccation (48 h) stress.

Annotation information was derived from L. monocytogenes N53-1 (GenBank accession no. CCQ22741.1).

P < 0.01 for the difference in survival compared to that of the WT.

P < 0.05 for the difference in survival compared to that of the WT.

P < 0.001 for the difference in survival compared to that of the WT.

Significantly (P < 0.05) lower survival during osmotic (49 h) stress than during desiccation (48 h) stress.

Annotation information was derived from L. monocytogenes N53-1 (GenBank accession no. CCQ22741.1).

FIG 1.

Colony morphology of the Listeria monocytogenes 568 wild type and its DT transposon mutants on BHI agar after 2 days of incubation at 30°C. (a) L. monocytogenes 568; (b) DT01 (lmo0289, yycH); (c and d) DT11 (lmo1371, lpd) plated on BHI after 49 h of osmotic stress (TSB-glu plus 20% NaCl, 15°C) (c) and 4 days of desiccation (43% RH, 15°C) (d).

After 1 and 7 days of desiccation, 9 and 14 of the 15 DS mutants, respectively, showed significantly (P < 0.05) impaired desiccation survival compared to that of the WT. For these mutants, final losses in viability ranged from 2.37 to 4.58 log CFU/cm2, whereas a final loss in viability of 1.72 log CFU/cm2 was observed for the WT (Table 2). All strains experienced the most inactivation within the first 24 h of desiccation. While some strains experienced little additional losses over the remaining desiccation period, the viability of others continued to steadily decrease throughout the 7 days. Five mutants (DS01, DS04, DS07, DS10, DS15) achieved a final mean reduction of >4 log CFU/cm2. Nine DS mutants were consistently significantly (P < 0.05) more susceptible to desiccation than the WT throughout the experiment (Table 2). It is important to note that even the most DS mutants had survival levels of ∼3.0 log CFU/cm2 after 7 days of desiccation on SS.

TABLE 2.

Transposon insertion sites identified in Listeria monocytogenes DS mutants mapped to the complete EGD-e sequenced genome and the corresponding losses in viability observed during desiccation and exposure to severe osmotic stressa

| L. monocytogenes strain | Gene locus tag | Gene name | Function | Survival reduction (mean ± SD Δlog CFU/cm2 [desiccation] or Δlog CFU/ml [osmotic stress]) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desiccation |

Osmotic stress at 49 h | |||||||

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 7 | |||||

| 568 | −1.48 ± 0.14 | −1.52 ± 0.12 | −1.74 ± 0.03 | −1.72 ± 0.15 | −0.74 ± 0.17 | |||

| DS01 | lmo0371-lmo0372 | Intergenic region | −2.71 ± 0.58b | −2.42 ± 0.34c | −2.66 ± 0.26d | −4.58 ± 0.99b | −0.76 ± 0.15e | |

| DS02 | lmo0565 | hisH | Imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase subunit | −2.02 ± 0.15 | −3.71 ± 0.82b | −3.00 ± 0.56c | −3.54 ± 0.19b | −0.61 ± 0.21e |

| DS03 | lmo0616 | Glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase | −2.15 ± 0.15 | −2.66 ± 0.16b | −3.23 ± 0.67b | −3.39 ± 0.05b | −0.66 ± 0.07e | |

| DS04 | lmo0983 | Glutathione peroxidase | −2.32 ± 0.12d | −2.39 ± 0.12c | −2.73 ± 0.14d | −4.09 ± 0.02b | −1.04 ± 0.00c | |

| DS05 | lmo1174 | eutA | Ethanolamine utilization protein | −2.13 ± 0.18 | −2.33 ± 0.13d | −2.27 ± 0.20 | −2.76 ± 0.04d | −1.19 ± 0.05b |

| DS06 | lmo1194 | cbiD | Cobalt-precorrin-6A synthase | −3.45 ± 0.50b | −3.43 ± 0.07b | −3.71 ± 0.36b | −3.97 ± 0.19b | −0.92 ± 0.06e |

| DS07 | lmo1219-lmo1220 or lmo1220 | Intergenic region or HxIR family transcriptional regulator | −2.29 ± 0.18d | −2.56 ± 0.14c | −2.64 ± 0.06d | −4.07 ± 0.45b | −1.16 ± 0.05b | |

| DS08 | lmo1728 | Cellobiose phosphorylase | −2.80 ± 0.09b | −3.03 ± 0.29b | −3.05 ± 0.20c | −3.27 ± 0.96b | −1.25 ± 0.06b | |

| DS09 | lmo2443 | Glutamate tRNA ligasef | −3.11 ± 0.76b | −2.96 ± 0.04b | −3.09 ± 0.89c | −3.71 ± 0.27b | −0.62 ± 0.15e | |

| DS10 | lmo2470 | Internalin | −2.78 ± 0.21b | −2.85 ± 0.18b | −3.05 ± 0.32c | −4.06 ± 0.33b | −0.84 ± 0.17e | |

| DS11 | lmo2490 | csbA | CsbA | −1.54 ± 0.37 | −2.05 ± 0.32 | −1.97 ± 0.31 | −2.48 ± 0.10 | −0.48 ± 0.13 |

| DS12 | lmo2503 | Cardiolipin synthase | −1.96 ± 0.18 | −2.42 ± 0.32c | −2.59 ± 0.28 | −3.78 ± 0.24b | −1.06 ± 0.06c | |

| DS13 | lmo2768 | Permease | −1.54 ± 0.37 | −1.90 ± 0.48 | −2.55 ± 0.69 | −2.81 ± 0.20d | −0.88 ± 0.17e | |

| DS14 | lmo2768 | Permease | −2.44 ± 0.00c | −2.78 ± 0.17b | −3.06 ± 0.03c | −2.99 ± 0.16c | −0.73 ± 0.03e | |

| DS15 | lmo2778 | Uncharacterized protein | −2.48 ± 0.24c | −2.88 ± 0.09b | −3.20 ± 0.12c | −4.10 ± 0.21b | −1.06 ± 0.07c | |

Cells were desiccated for 7 days at 43% RH and 15°C in TSB plus 1% glucose on SS coupons at an initial concentration of 7.5 log CFU/cm2. Osmotic stress survival was determined by resuspending TSB-glu-grown cultures to 7.5 log CFU/ml in TSB-glu plus 20% NaCl for 49 h at 15°C (n = 3). The complete L. monocytogenes EGD-e sequenced genome can be found in GenBank under accession number NC_003210.

P < 0.001 for the difference in survival compared to that of the WT.

P < 0.01 for the difference in survival compared to that of the WT.

P < 0.05 for the difference in survival compared to that of the WT.

The mutants displayed significantly (P < 0.05) decreased survival after 33 h of osmotic stress compared to the wild type.

Annotation information was derived from L. monocytogenes N53-1 (GenBank accession no. CCQ25113.1).

Location of transposon insertion sites.

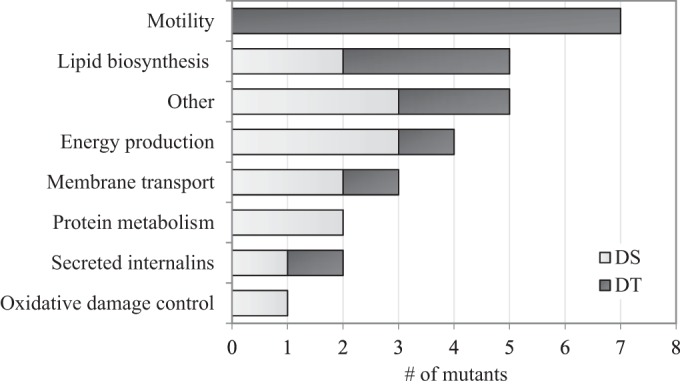

DNA sequences flanking both sides (left and right) of the transposon insertion site were successfully obtained for 26 mutants using the arbitrary PCR method. For these mutants, identification of corresponding left and right sequences made it likely that only one transposon was inserted. Additional primers were designed to amplify the unsuccessfully sequenced side in four mutants (DS01, DS07, DS09, DS10). Although the location of one transposon was confirmed in these mutants, the possibility of the presence of other transposons, however unlikely, cannot be excluded. Overall, the exact insertion site of 19 transposons was identified, whereas in EGD-e the mapped locations of the left and right sequences were separated by 1 bp in seven mutants and 3, 6, 20, and 52 bp in the remaining four mutants, respectively (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). These gaps may be a result of the arbitrary PCR method, sequence quality, or discrepancies between the sequences of the genomes of L. monocytogenes 568 and EGD-e. The gene identities and their known or predicted functions are listed in Tables 1 and 2 for the DT and DS mutants, respectively. The prevalence of specific gene functional groups is displayed in Fig. 2, and the distribution of insertion sites mapped to the EGD-e chromosome is shown in Fig. 3.

FIG 2.

Putative functions of the interrupted genes in 15 desiccation-tolerant (DT) and 15 desiccation-sensitive (DS) Listeria monocytogenes 568 Himar1 transposon insertion mutants. Note that two DS mutants contained transposons in the same gene, making the total number of affected genes 14.

FIG 3.

Locations of the sequenced Himar1 transposon insertion sites in desiccation-tolerant and -sensitive Listeria monocytogenes 568 mutants mapped to the EGD-e chromosome. Each quarter of the chromosome is identified with the approximate base pair, except for bp 1, which is identified by an arrow.

The interrupted genes in seven DT mutants were associated with motility, including flagellar biosynthesis (fliP, flhB, flgD, flgL) and motor control (motB, fliM, fliY). Other affected genes in DT mutants were classified as contributing to membrane lipid biosynthesis (buk, lpd, yycH), potassium uptake (lmo0771), energy production (adeC), and virulence (inlC).

The extremely desiccation-tolerant mutants DT10 and DT11 harbored transposons in neighboring genes (lmo1370 and lmo1371, respectively) encoding butyrate kinase (buk) and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (lpd), respectively, which are involved in fatty acid (FA) metabolism. Mutants DT13 and DT14 also exhibited insertions in nearby genes (lmo1742 and lmo1744, respectively) encoding adenine deaminase and an NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase, respectively.

The transposon location in the remaining four DT mutants was mapped to dispersed locations in the EGD-e chromosome. In mutant DT01, the affected gene (lmo0289, yycH) encodes a regulatory protein of the sensory box histidine kinase two-component system (TCS) YycFG which is involved in cell wall homeostasis, membrane integrity, and cell division. Mutant DT09 had an affected ATP-sensitive inward rectifier potassium channel (lmo0771), and mutants DT12 and DT15 had an interrupted adenine-specific DNA methylase (lmo1582) and internalin C (inlC), respectively.

In the DS mutants, most transposon insertions were mapped to one of three areas of the EGD-e chromosome. The first cluster encompassed mutants DS05 to DS07 with insertions in lmo1174, lmo1194, and either the intergenic region of lmo1219-lmo1220 or lmo1220, respectively. These genes encode an ethanolamine utilization protein (EutA), a cobalt-precorrin-6A synthase (CbiD), and an intergenic region or an HxIR DNA binding protein (lmo1220), respectively. The second area included mutants DS09 to DS12 and involved the genes lmo2443, lmo2470, lmo2490, and lmo2503, respectively. The first gene, lmo2443, encodes glutamate tRNA ligase, while lmo2470 is a L. monocytogenes-specific secreted internalin. The gene lmo2490 encodes CsbA, a σB-regulated transmembrane general stress response protein, and lmo2503 is a cardiolipin synthase.

The last cluster of DS-associated transposon insertion sites were found in mutants DS13 and DS14, both of which contained the transposon in lmo2768, an uncharacterized membrane transport protein, and mutant DS15, which contained a transposon in lmo2778, encoding an uncharacterized protein consisting of 170 amino acids.

Among the remaining five unclustered DS mutants were DS01 to DS04 and DS08. DS01 contained a transposon in the intergenic region between the genes lmo0371 and lmo0372, which encode a GntR family transcriptional regulator and beta-glucosidase, respectively, with lmo0371 being individually transcribed and encoded on the complement strand. Mutant DS02 contained the transposon in lmo0565, corresponding to the HisH subunit of imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase. The affected gene (lmo0616) in mutant DS03 was that for glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase, which acts on membrane glycerophospholipids. Lastly, mutants DS04 and DS08 contained transposons in genes lmo0983 and lmo1728, respectively, encoding glutathione peroxidase and cellobiose-phosphorylase, respectively.

Osmotic stress survival.

Five DT mutants also demonstrated significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced osmotic stress survival after 49 h of exposure to 20% NaCl (Table 1). For these mutants, mean final losses ranged from 0.10 to 0.41 log CFU/ml, whereas the loss for the WT was 0.74 log CFU/ml (Table 1). Three of the most osmotolerant mutants harbored transposons in flagellar biosynthesis- and structure-related genes (fliP, flhB, flgL), whereas two DT flagellar mutants with interrupted motor control genes (fliM, motB) exhibited significantly (P < 0.05) reduced osmotolerance. Seven other DT mutants showed initial osmotolerance relative to the tolerance of the WT; however, the overall losses after 49 h were not significantly (P > 0.05) different. The colony morphology of mutant DT11, which took on a donut shape when cultured after desiccation on SS coupons, displayed irregularly shaped colonies after exposure to high salt concentrations (Fig. 1).

Of the 15 DS mutants, 14 displayed significantly (P < 0.05) impaired osmotolerance after 33 h (data not shown). This impairment remained significant for seven mutants after 49 h of exposure, with mean final losses ranging from 0.92 to 1.25 log CFU/ml (Table 2). The most osmosensitive (OS) mutants (DS05, DS07, and DS08) displayed >1.15-log-CFU/ml mean final reductions in survival, and all contained transposons in genes associated with energy production.

When directly comparing the effect of osmotic and desiccation stresses after 49 and 48 h, respectively, four DT mutants (DT04, DT10, DT11, and DT15) displayed significantly (P < 0.05) higher survival levels after desiccation stress than after osmotic stress, while four mutants (DT01, DT03, DT05, and 09) displayed significantly (P < 0.05) lower survival levels after osmotic stress (Table 1). In contrast, all DS mutants had significantly (P < 0.05) lower survival levels following desiccation stress than following osmotic stress (Table 2). With the exception of the extremely desiccation-tolerant mutants DT10 and DT11, all mutants exhibited lower viability losses after they were exposed to 20% NaCl for 49 h than after they were desiccated at 43% RH for 7 days.

Motility assay and flagellum staining.

Only mutants that contained transposon insertions in flagellum-associated genes exhibited a lack of motility at 15°C. Light microscopy further demonstrated that these seven mutants were devoid of flagella (data not shown). Additionally, the motility of the lmo1582 mutant was reduced in comparison to that of the WT.

Heat tolerance assay.

After 30 min at 55°C, mutant DT10 (buk) showed only a 0.84-log-CFU/ml reduction in survival, which was significantly (P < 0.05) less than the 2.15-log-CFU/ml reduction demonstrated by the WT.

Expression of flagellum-associated genes in desiccation-tolerant immotile mutants.

To elucidate whether the transposon insertion caused any downstream polar effects in the mutants with mutations in flagellum-associated genes, endpoint RT-PCR was performed to detect the expression of the affected gene and the gene directly downstream in each of the seven mutants (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Expression of 16S rRNA and flaA in all mutants and the WT confirmed successful cDNA conversions. While stationary-phase cells of the WT strain grown at 15°C expressed all of the tested flagellum-associated genes, none of the affected genes were transcribed in the mutants with mutations in flagellum-associated genes (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). While the immediately adjacent downstream genes were expressed in the fliP, flhB, flgD, and motB insertional mutants, they were not expressed in the fliM, fliY, and flgL mutants, demonstrating possible polar effects of the transposon insertion in some mutants.

DISCUSSION

In this study, insertional mutagenesis in L. monocytogenes 568 led to the identification of 30 loci with putative roles in desiccation stress survival, and 19 of these similarly influenced osmotic stress survival.

Impaired motility is associated with enhanced desiccation tolerance.

Desiccation tolerance and impaired motility in seven mutants were attributed to interruptions in flagellum-associated genes. Additionally, three of these mutants displayed enhanced osmotolerance, suggesting that the downregulation of flagellum-associated gene expression may be a valuable survival mechanism for cells experiencing water stress. A study which compared the transcriptome profiles of a DT strain and a DS strain of Salmonella after 2 h of drying saw inhibition of flagellum-associated gene expression in the DT strain relative to the level of flagellum-associated gene expression in the DS strain (23). The downregulation of flagellum-associated genes has also been observed in Pseudomonas putida cells exposed to matric and, to a lesser extent, solute stresses (32) and Bacillus subtilis exposed to osmotic stress (33). Additional studies report conflicting results on the importance of flagella in desiccation survival (25, 34). In the present study, three mutants with mutations in flagellum-associated structural gene (fliP, flhB, flgL) displayed the greatest osmotolerance observed among all the mutants, whereas two mutants with mutations in flagellum motor control (motB, fliM) showed significantly decreased osmotolerance. This demonstrates that different osmotolerance phenotypes can exist within motility-impaired DT strains of L. monocytogenes.

Flagellum biosynthesis is an energy-consuming endeavor, and so it would likely be beneficial for bacterial cells experiencing stress to downregulate flagellum-associated gene expression and redirect their energy into more critical metabolic processes. Recently, it was shown that immotile L. monocytogenes mutants were capable of forming hyperbiofilms under dynamic but not static conditions (35). Similar results have also been reported in Bacillus cereus (36). Together with the possibility of increased desiccation tolerance and osmotolerance, immotile strains of L. monocytogenes may pose a greater threat to the food industry. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report an association between flagellum-associated gene expression and desiccation survival in L. monocytogenes.

The insertion sites in these mutants were mapped to four transcriptional units (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) that encompass 33 of the 41 flagellum-associated genes in L. monocytogenes. The affected gene was not expressed in any of the seven mutants (see Table S5 in the supplemental material), making this likely true for all the transposon mutants. In four mutants (with mutations in fliP, flhB, motB, and flgD) the downstream gene continued to be expressed, whereas in the other three (with mutations in fliM, fliY, and flgL), the transposon insertion caused a polar effect and abolished the expression of the downstream gene. The successful amplification of flaA, which is an individually transcribed gene upstream of the transposon in these three mutants, demonstrates that the polar effect remained local. With the exception of motB, previous literature confirms that when these genes are deleted in L. monocytogenes and other motile bacteria, nonflagellated mutants result (37–41). Unlike the other proteins, MotB is not part of the core flagellum structure but is an associated transmembrane protein required for the rotation of the flagellum motor. Therefore, clean motB mutants are flagellated but immotile (42, 43). It remains unknown why flagella were not observed on the motB mutant in this study, since the mutation did not appear to impact the expression of downstream genes. However, regardless of whether an immotile strain is flagellated or not, strains of both phenotypes would largely benefit from the reduced energy commitment of powering flagellar rotation (reviewed in reference 44).

Fatty acid metabolism and a putatively less fluid membrane are involved in desiccation tolerance.

Many of the desiccation mutants, both tolerant and sensitive, contained an affected gene which is associated with FA biosynthesis and, putatively, the cell membrane composition. This is not surprising, given the importance of membrane viscosity and integrity in the survival of bacteria exposed to other environmental stresses, including pH and temperature extremes, high osmolarity, hydrostatic pressure, and transition to stationary phase (45–49). In Listeria and related bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and B. subtilis, >90% of cellular membrane FAs are branched-chain FAs (BCFAs) and therefore the major determinants of membrane fluidity (50). Critical for the synthesis of BCFAs is a multisubunit branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase (BKD) complex. The first two genes of the bkd locus encode dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (lpd) and butyrate kinase (buk), the affected genes in two mutants (DT10 and DT11) which exhibited extreme desiccation tolerance (<0.2-log-CFU/cm2 reduction after 7 days). In agreement with an earlier report (31), the buk mutant also exhibited increased heat resistance, and both mutants were significantly (P < 0.05) more osmotolerant than the WT. In B. subtilis, L. monocytogenes, and S. aureus, it has been demonstrated that BKD-deficient mutants have less fluid membranes due to reduced levels of BCFAs and increased levels of straight-chain FAs (50–52). Severe growth defects, longer generation times, and reduced maximal growth in rich media (52) have also been reported, in agreement with our observations of low growth rates for the lpd and buk mutants and the unusual colony morphologies exhibited by the lpd mutant under desiccation and osmotic stress conditions (Fig. 1). These results suggest that inactivation of the listerial BKD complex may be associated with enhanced desiccation tolerance and, in some cases, heat tolerance and osmotolerance.

Exponential-phase bacterial cells are normally less resistant to various stresses than stationary-phase cells (53–56). However, this was not observed with the lpd and buk mutants, where late-exponential-phase cells had increased resistance relative to WT stationary-phase cells.

The interrupted gene in another DT mutant encodes the regulatory protein YycH of the YycFG (recently renamed WalKR) two-component system essential for cell viability in Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus, B. subtilis, L. monocytogenes, and Enterococcus faecalis (57). YycH negatively controls WalK activity, and without this control, the overexpression of WalKR results in increased synthesis of longer-chain FAs, producing a less fluid membrane (58). yycH deletion mutants demonstrated growth impairments and cell wall defects (59, 60), which may partly explain the irregularly shaped colonies observed for the yycH transposon mutant in our study (Fig. 1).

Numerous studies have reported the upregulation of FA biosynthesis genes in bacteria subjected to dehydration or matric stresses (22, 23, 25, 32, 34). In both Salmonella (23) and Pseudomonas putida (32), exposure to matric stress resulted in the upregulation of enzymes that degrade long-chain FAs and damaged phospholipids. This may increase the energy yield under starvation conditions, as FA oxidation generates significantly more ATPs per carbon atom than glucose (61). Additionally, these studies also saw the upregulation of enzymes involved in altering the membrane composition to produce a more rigid, less fluid membrane. Such changes, including increased levels of saturated FAs and cardiolipin, have also been reported in B. subtilis (62, 63), Escherichia coli (64), and S. aureus (65) subjected to salt stress, which produced thicker cell walls, possibly preventing NaCl entrance and the escape of compatible solutes (62). Increased levels of saturated FAs also increase the melting point of the membrane, making cells more resistant to higher temperatures (66). Salmonella cells preexposed to alkaline and acidic conditions developed membranes which contained higher levels of saturated FAs and lower levels of unsaturated FAs that subsequently induced thermotolerance (67, 68). An increased percentage of saturated FAs may also limit the effects of lipid oxidation imposed by high temperatures, dehydration, and osmotic stress. Overlaps among stress adaptation mechanisms are logical due to redundancies in regulatory networks contributing to general and specific stress responses (69).

As mentioned previously, cardiolipin levels positively correlate with increased osmotolerance, cold tolerance, and acid tolerance in both L. monocytogenes and other bacteria alike (62, 65, 70). This diphosphatidylglycerol lipid is a multifunctional molecule that participates in cell division, energy metabolism, and membrane transport (71). In this study, interruption of cardiolipin synthase produced a desiccation- and osmosensitive mutant, further underscoring its role in adapting to environments with low water levels. Similarly, a mutant containing an interrupted glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase, an enzyme involved in the production of glycerophospholipids and cardiolipin, also demonstrated desiccation sensitivity and osmosensitivity.

Energy sources related to desiccation survival.

Several desiccation mutants harbored transposons in genes that may provide alternative energy sources during desiccation stress. Two DS mutants contained nearby affected genes involved in ethanolamine utilization (eutA) and vitamin B12 synthesis (cbiD). EutA is a putative chaperonin that prevents the inhibition of ethanolamine ammonia lyase (EutBC), an enzyme believed to be necessary for L. monocytogenes to utilize ethanolamine as a carbon and nitrogen source under intracellular nutrient-limited conditions (72–74). The means of regulation of the eut operon in Listeria remains unknown, but in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium it is activated by both ethanolamine and vitamin B12 under anaerobic conditions (75, 76). In L. monocytogenes, transcription of vitamin B12 biosynthesis genes is induced during intracellular growth (73), suggesting that its eut operon is similarly regulated. This points to the putative importance of mobilizing ethanolamine at the expense of membrane phosphatidylethanolamine as an energy source to survive the starvation conditions induced under desiccation stress conditions. In support of this suggestion is the finding that enzymes involved in the degradation of phospholipids are upregulated during exposure to dehydration stress (32). These mutants also displayed significant osmosensitivity.

Interruption of adenine deaminase (adeC) was found to produce a desiccation- and osmotolerant mutant. As adenine is taken up by cells, it is either phosphoribosylated to AMP or deaminated to produce nucleotide precursors (77). Under starvation conditions, adenine can act as a sole C and N source for bacteria via the AMP pathway. Since desiccated cells also experience starvation stress, it may be hypothesized that inactivation of adeC allows cells to utilize adenine solely as an energy source, which could be more advantageous for survival.

Lastly, the interrupted gene in a desiccation- and osmosensitive mutant was identified to be cellobiose phosphorylase (lmo1728). Cellobiose phosphorylase is responsible for the intracellular breakdown of cellobiose to glucose monomers (78). A mutant defective in cellobiose metabolism would be unable to use the cellobiose in the TSB used in both the desiccation tolerance and osmotolerance assays, which would possibly cause starvation and decreased survival compared to that of the WT.

Amino acid metabolism and desiccation survival.

Two DS mutants contained inserts in genes involved in protein metabolism, specifically, histidine biosynthesis and glutamate utilization. The affected gene, hisH, is cotranscribed with hisB, hisD, hisG, and hisZ to produce enzymes required for histidine biosynthesis. The other identified gene encodes glutamate-tRNA ligase, 1 of 20 aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases essential for protein synthesis. The upregulation of glutamate metabolism genes, including Glu-tRNA ligase (79), and the intracellular accumulation of glutamate have been shown to enhance survival during osmotic, acid, and bile stress in L. monocytogenes (80, 81) and other bacteria (82). Interruption of lmo2443 may cause glutamate to accumulate in the cell, which could be an explanation for the increased osmotolerance observed in this mutant. The hisH mutant also displayed significantly enhanced osmotolerance; however, the reasons for this remain speculative. In a transcriptomic analysis of desiccated Salmonella, nearly half of the upregulated genes belonged to 10 operons, 3 of which were involved in the metabolism of arginine, histidine, and glutamate (22), suggesting that these amino acids may play a specific role in desiccation survival.

Oxidation damage control and desiccation survival.

Biomolecules in low-water-activity environments are more susceptible to oxidation due to increased cytoplasm ion concentrations and the formation of reactive oxygen species (83). These reactive species can damage proteins by modifying amino acid side chains, forming cross-links between proteins, and causing DNA backbone chain breaks (84, 85). Additionally, they can cause lipid peroxidation in cell membranes (86). Therefore, it is not surprising that we identified a desiccation- and osmosensitive mutant with an affected glutathione peroxidase gene (lmo0983), known to prevent oxidative damage.

Internalins with putative impacts on desiccation survival.

Internalin C (inlC) and lmo2470, the affected genes in a DT mutant and a DS mutant, respectively, are among 25 known Listeria-specific internalin proteins (87, 88). Aside from their most recognized roles in intracellular invasion (inlA, inlB), internalins contain a leucine-rich repeat domain that allows them to bind structurally unrelated protein ligands, thereby implicating them in a wide range of functions. Most internalins are cell wall-anchored proteins, but both inlC and lmo2470 fall into a small class of four secreted internalins. Studies have shown that inlC is upregulated during late stages of intracellular infection (89); however, the role of lmo2470 remains to be elucidated.

Once they are in vivo, intracellular pathogens are faced with a number of harsh conditions, including nutrient and oxygen starvation and osmotic and acid stress. One of the main stress response regulators in L. monocytogenes is σB, which also regulates genes expressed during infection (90), including inlC (91). In desiccated Salmonella, four of seven downregulated genes were found to be located on the virulence plasmid (22). This suggests that the inactivation of virulence genes with little or no role in stress survival may be an advantageous energy conservation mechanism for surviving desiccation.

Contrary to the results of inhibition of inlC, inhibition of lmo2470 produced a desiccation- and osmosensitive mutant. Although the function of this internalin remains speculative, it is one of eight internalins found among Listeria spp. that is unique to L. monocytogenes (92). Therefore, any role that it may have in the stress response of the pathogen could potentially allow L. monocytogenes to outcompete nonpathogenic Listeria strains in food processing environments.

Membrane transport proteins associated with desiccation survival.

Two DS mutants that also displayed osmosensitivity harbored their transposon in the same gene, lmo2768, encoding a membrane transport protein. A third DS mutant also contained an interrupted membrane protein (csbA) that is regulated by σB and involved in the general stress response (93). Membrane transport proteins are important for adaptation to low-water-activity environments to facilitate uptake of the different nutrients and/or osmolytes required by dehydrated cells (32).

When cells encounter osmotic stress, their first response mechanism is the upregulation of membrane transporters that scavenge K+ from the environment to help maintain cell turgor pressure (94, 95). Surprisingly, in this study we identified a desiccation- and osmotolerant mutant with an interrupted ATP-sensitive inward potassium channel (lmo0771). A possible explanation could be that a more efficient K+ transporter, such as KdpFABC, makes the inhibition of less efficient ATP-dependent K+ transporters an energy-saving event during desiccation stress. Several genes of the kdpFABC operon were found to be upregulated in Salmonella (22) and cyanobacteria (96) in response to desiccation. The importance of this system in L. monocytogenes and E. coli survival under conditions of osmotic and low-temperature stress has also been documented (95, 97), indicating a possible role for this operon during desiccation stress.

Other affected genes.

A DT mutant contained a mutated adenine-specific DNA methylase (dam, lmo1582) which has been elucidated in E. coli and S. enterica to methylate adenosine residues in 5′-GATC-3′ sites postreplication, therefore altering the DNA structure and subsequent protein binding (98, 99). In these bacteria Dam− mutants exhibited attenuated virulence related to decreased expression of virulence-related fimbriae and invasion proteins (100, 101). Motility-related genes were also found to be downregulated relative to their levels of regulation in the WT, whereas genes belonging to the SOS response regulon were upregulated (102, 103). Possible reasons why decreased motility, which was also observed in the L. monocytogenes DT mutant, and virulence gene expression might increase desiccation survival have been previously discussed; however, given that the SOS response in L. monocytogenes has been associated with stress resistance (104) and heat shock (105), it may be that this regulon also has a role in desiccation survival.

Another DT mutant also displaying osmotolerance contained an interrupted NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase. This class of enzymes possesses oxidoreductase activity that is central to both carbohydrate and lipid metabolic processes. More research is needed to determine the exact role of this enzyme in desiccation and osmotic stress.

In the desiccation- and osmosensitive mutant DS07, a 20-bp gap in the sequencing results made it unknown whether the transposon was inserted in lmo1220 or the lmo1219-lmo1220 intergenic space. Regardless, the close proximity of any insertion in the intergenic region may alter the expression of lmo1220, which encodes the DNA binding protein HxIR. This protein positively regulates the hxlAB operon, encoding two key enzymes in the ribulose monophosphate pathway responsible for the detoxification of formaldehyde in Bacillus subtilis (106–108). Formaldehyde is produced in many microorganisms through the degradation of organic compounds that have methyl or methoxy groups, e.g., lignin and pectin. Interruption of HxIR expression in this mutant may be hypothesized to result in a toxic intracellular buildup of formaldehyde, which would decrease its survival under both stresses.

A noteworthy finding is that all DS mutants still retained cell viabilities of >3.0 log CFU/cm2 after 7 days of desiccation. Recently, we compared the desiccation survival of three Gram-negative spoilage bacteria and L. monocytogenes on stainless steel and found that the levels of Shewanella baltica and Pseudomonas fluorescens dropped below the detection limit after 7 days of desiccation (43% RH, 15°C), while Serratia proteamaculans displayed survival similar to that of L. monocytogenes (109). Similarly, L. monocytogenes has been shown to have desiccation tolerance superior to that of S. aureus and Salmonella Typhimurium (18). This implies that even desiccation-sensitive strains of L. monocytogenes may still outcompete less-desiccation-tolerant microorganisms found in food processing environments.

This study is the first to report on the multiple genes influencing the desiccation survival of L. monocytogenes, with many being found to be involved in motility, membrane lipid biosynthesis, energy production, membrane transport, protein metabolism, and putative virulence. Gene interruptions in 19 mutants led to survival trends similar to those for the WT under both desiccation and osmotic stress conditions, whereas the affected genes in the remaining 11 mutants solely affected desiccation survival. This demonstrates that both similar and different mechanisms are used by L. monocytogenes to survive the dehydration imposed by solute and matric stresses. Future characterization of the affected regulons will help identify desiccation resistance mechanisms in L. monocytogenes and ultimately lead to improved control of Listeria in food processing environments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Council (NSERC) Julie Payette Research Scholarship to P. A. Hingston, a Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation Ph.D. scholarship to M. J. Piercey, and an NSERC Discovery Grant to L. Truelstrup Hansen.

Laura Purdue is thanked for her technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01134-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cartwright EJ, Jackson KA, Johnson SD, Graves LM, Silk BJ, Mahon BE. 2013. Listeriosis outbreaks and associated food vehicles, United States, 1998–2008. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1901.120393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd E, Notermans S. 2011. Surveillance of listeriosis and its causative pathogen, Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control 22:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yildiz O, Aygen B, Esel D, Kayabas U, Alp E, Sumerkan B, Doganay M. 2007. Sepsis and meningitis due to Listeria monocytogenes. Yonsei Med J 48:433–439. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2007.48.3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen SJ, Patrick M, Hunter SB, Reddy V, Kornstein L, MacKenzie WR, Lane K, Bidol S, Stoltman GA, Frye DM. 2005. Multistate outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infection linked to delicatessen turkey meat. Clin Infect Dis 40:962–967. doi: 10.1086/428575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Multistate outbreak of listeriosis associated with Jensen Farms cantaloupe—United States, August-September 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60:1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mead P, Dunne E, Graves L, Wiedmann M, Patrick M, Hunter S, Salehi E, Mostashari F, Craig A, Mshar P. 2006. Nationwide outbreak of listeriosis due to contaminated meat. Epidemiol Infect 134:744–751. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805005376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infections associated with pasteurized milk from a local dairy—Massachusetts, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57:1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson K, Biggerstaff M, Tobin-D'Angelo M, Sweat D, Klos R, Nosari J, Garrison O, Boothe E, Saathoff-Huber L, Hainstock L. 2011. Multistate outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes associated with Mexican-style cheese made from pasteurized milk among pregnant, Hispanic women. J Food Prot 74:949–953. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simmons C, Stasiewicz MJ, Wright E, Warchocki S, Roof S, Kause JR, Bauer N, Ibrahim S, Wiedmann M, Oliver HF. 2014. Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria spp. contamination patterns in retail delicatessen establishments in three U.S. states. J Food Prot 77:1929–1939. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varma JK, Samuel MC, Marcus R, Hoekstra RM, Medus C, Segler S, Anderson BJ, Jones TF, Shiferaw B, Haubert N. 2007. Listeria monocytogenes infection from foods prepared in a commercial establishment: a case-control study of potential sources of sporadic illness in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 44:521–528. doi: 10.1086/509920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoelzer K, Oliver HF, Kohl LR, Hollingsworth J, Wells MT, Wiedmann M. 2012. Structured expert elicitation about Listeria monocytogenes cross-contamination in the environment of retail deli operations in the United States. Risk Anal 32:1139–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Destro M, Leitao M, Farber J. 1996. Use of molecular typing methods to trace the dissemination of Listeria monocytogenes in a shrimp processing plant. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:705–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundén JM, Miettinen MK, Autio TJ, Korkeala HJ. 2000. Persistent Listeria monocytogenes strains show enhanced adherence to food contact surface after short contact times. J Food Prot 63:1204–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker S, Archer P, Banks JG. 1990. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes at refrigeration temperatures. J Appl Bacteriol 68:157–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, Lawrence ML, Ainsworth AJ, Austin FW. 2005. Comparative assessment of acid, alkali and salt tolerance in Listeria monocytogenes virulent and avirulent strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett 243:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogel BF, Hansen LT, Mordhorst H, Gram L. 2010. The survival of Listeria monocytogenes during long term desiccation is facilitated by sodium chloride and organic material. Int J Food Microbiol 140:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hingston PA, Stea EC, Knøchel S, Hansen T. 2013. Role of initial contamination levels, biofilm maturity and presence of salt and fat on desiccation survival of Listeria monocytogenes on stainless steel surfaces. Food Microbiol 36:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi H, Kuramoto S, Miya S, Kimura B. 2011. Desiccation survival of Listeria monocytogenes and other potential foodborne pathogens on stainless steel surfaces is affected by different food soils. Food Control 22:633–637. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Truelstrup Hansen L, Vogel BF. 2011. Desiccation of adhering and biofilm Listeria monocytogenes on stainless steel: survival and transfer to salmon products. Int J Food Microbiol 146:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.França M, Panek A, Eleutherio E. 2007. Oxidative stress and its effects during dehydration. Comp Biochem Phys A 146:621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billi D, Potts M. 2002. Life and death of dried prokaryotes. Res Microbiol 153:7–12. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruzdev N, McClelland M, Porwollik S, Ofaim S, Pinto R, Saldinger-Sela S. 2012. Global transcriptional analysis of dehydrated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:7866–7875. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01822-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Bhaskara A, Megalis C, Tortorello ML. 2012. Transcriptomic analysis of Salmonella desiccation resistance. Foodborne Pathog Dis 9:1143–1151. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Mortel M, Chang W-S, Halverson L. 2004. Differential tolerance of Pseudomonas putida biofilm and planktonic cells to desiccation. Biofilms 1:361–368. doi: 10.1017/S1479050504001528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gülez G, Dechesne A, Workman CT, Smets BF. 2012. Transcriptome dynamics of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 under water stress. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:676–683. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06150-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalmokoff M, Austin J, Wan XD, Sanders G, Banerjee S, Farber J. 2001. Adsorption, attachment and biofilm formation among isolates of Listeria monocytogenes using model conditions. J Appl Microbiol 91:725–734. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao M, Bitar AP, Marquis H. 2007. A mariner-based transposition system for Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2758–2761. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02844-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander JE, Andrew P, Jones D, Roberts I. 1990. Development of an optimized system for electroporation of Listeria species. Lett Appl Microbiol 10:179–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1990.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garsin DA, Urbach J, Huguet-Tapia JC, Peters JE, Ausubel FM. 2004. Construction of an Enterococcus faecalis Tn917-mediated-gene-disruption library offers insight into Tn917 insertion patterns. J Bacteriol 186:7280–7289. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7280-7289.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaser P, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Rusniok C, Amend A, Baquero F, Berche P, Bloecker H, Brandt P, Chakraborty T, Charbit A, Chetouani F, Couvé E, de Daruvar A, Dehoux P, Domann E, Domínguez-Bernal G, Duchaud E, Durant L, Dussurget O, Entian K-D, Fsihi H, Garcia-Del Portillo F, Garrido P, Gautier L, Goebel W, Gómez-López N, Hain T, Hauf J, Jackson D, Jones L-M, Kaerst U, Kreft J, Kuhn M, Kunst F, Kurapkat G, Madueño E, Maitournam A, Mata Vicente J, Ng E, Nedjari H, Nordsiek G, Novella S, de Pablos B, Pérez-Diaz J-C, Purcell R, Remmel B, Rose M, Schlueter T, Simoes N, et al. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849–852. doi: 10.1126/science.1063447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ells TC, Speers RA, Truelstrup Hansen L. 2009. Insertional mutagenesis of Listeria monocytogenes 568 reveals genes that contribute to enhanced thermotolerance. Int J Food Microbiol 136:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van De Mortel M, Halverson LJ. 2004. Cell envelope components contributing to biofilm growth and survival of Pseudomonas putida in low-water-content habitats. Mol Microbiol 52:735–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hahne H, Mäder U, Otto A, Bonn F, Steil L, Bremer E, Hecker M, Becher D. 2010. A comprehensive proteomics and transcriptomics analysis of Bacillus subtilis salt stress adaptation. J Bacteriol 192:870–882. doi: 10.1128/JB.01106-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cytryn EJ, Sangurdekar DP, Streeter JG, Franck WL, Chang W-S, Stacey G, Emerich DW, Joshi T, Xu D, Sadowsky MJ. 2007. Transcriptional and physiological responses of Bradyrhizobium japonicum to desiccation-induced stress. J Bacteriol 189:6751–6762. doi: 10.1128/JB.00533-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Todhanakasem T, Young GM. 2008. Loss of flagellum-based motility by Listeria monocytogenes results in formation of hyperbiofilms. J Bacteriol 190:6030–6034. doi: 10.1128/JB.00155-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houry A, Briandet R, Aymerich S, Gohar M. 2010. Involvement of motility and flagella in Bacillus cereus biofilm formation. Microbiology 156:1009–1018. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garbe J, Bunk B, Rohde M, Schobert M. 2011. Sequencing and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage JG004. BMC Microbiol 11:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohnishi K, Ohto Y, Aizawa S, Macnab RM, Iino T. 1994. FlgD is a scaffolding protein needed for flagellar hook assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 176:2272–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foynes S, Dorrell N, Ward SJ, Zhang ZW, McColm AA, Farthing MJ, Wren BW. 1999. Functional analysis of the roles of FliQ and FlhB in flagellar expression in Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett 174:33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bischoff D, Weinreich M, Ordal G. 1992. Nucleotide sequences of Bacillus subtilis flagellar biosynthetic genes fliP and fliQ and identification of a novel flagellar gene, fliZ. J Bacteriol 174:4017–4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bischoff DS, Ordal GW. 1992. Identification and characterization of FliY, a novel component of the Bacillus subtilis flagellar switch complex. Mol Microbiol 6:2715–2723. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorski L, Duhé JM, Flaherty D. 2009. The use of flagella and motility for plant colonization and fitness by different strains of the foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS One 4:e5142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doyscher D, Fieseler L, Dons L, Loessner MJ, Schuppler M. 2013. Acanthamoeba feature a unique backpacking strategy to trap and feed on Listeria monocytogenes and other motile bacteria. Environ Microbiol 15:433–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berg HC. 2003. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Biochemistry 72:19. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Juneja VK, Foglia TA, Marmer BS. 1998. Heat resistance and fatty acid composition of Listeria monocytogenes: effect of pH, acidulant, and growth temperature. J Food Prot 61:683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Annous BA, Kozempel MF, Kurantz MJ. 1999. Changes in membrane fatty acid composition of Pediococcus sp. strain NRRL B-2354 in response to growth conditions and its effect on thermal resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:2857–2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casadei M, Manas P, Niven G, Needs E, Mackey B. 2002. Role of membrane fluidity in pressure resistance of Escherichia coli NCTC 8164. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:5965–5972. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.5965-5972.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russell N, Evans R, Ter Steeg P, Hellemons J, Verheul A, Abee T. 1995. Membranes as a target for stress adaptation. Int J Food Microbiol 28:255–261. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(95)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neidhardt FC, Curtiss R III, Ingraham JL, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, Reznikoff WS, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE (ed). 1996. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed, vol 2 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh VK, Hattangady DS, Giotis ES, Singh AK, Chamberlain NR, Stuart MK, Wilkinson BJ. 2008. Insertional inactivation of branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase in Staphylococcus aureus leads to decreased branched-chain membrane fatty acid content and increased susceptibility to certain stresses. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:5882–5890. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00882-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willecke K, Pardee AB. 1971. Fatty acid-requiring mutant of Bacillus subtilis defective in branched chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem 246:5264–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu K, Ding X, Julotok M, Wilkinson BJ. 2005. Exogenous isoleucine and fatty acid shortening ensure the high content of anteiso-C15:0 fatty acid required for low-temperature growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:8002–8007. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8002-8007.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aryani D, den Besten H, Hazeleger W, Zwietering M. 2015. Quantifying variability on thermal resistance of Listeria monocytogenes. Int J Food Microbiol 193:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nair S, Finkel SE. 2004. Dps protects cells against multiple stresses during stationary phase. J Bacteriol 186:4192–4198. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4192-4198.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mackey B, Forestiere K, Isaacs N. 1995. Factors affecting the resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to high hydrostatic pressure. Food Biotechnol 9:1–11. doi: 10.1080/08905439509549881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luppens S, Abee T, Oosterom J. 2001. Effect of benzalkonium chloride on viability and energy metabolism in exponential- and stationary-growth-phase cells of Listeria monocytogenes. J Food Prot 64:476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dubrac S, Msadek T. 2008. Tearing down the wall: peptidoglycan metabolism and the WalK/WalR (YycG/YycF) essential two-component system, p 214–228. In Bacterial signal transduction: networks and drug targets. Springer, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohedano ML, Overweg K, de la Fuente A, Reuter M, Altabe S, Mulholland F, de Mendoza D, López P, Wells JM. 2005. Evidence that the essential response regulator YycF in Streptococcus pneumoniae modulates expression of fatty acid biosynthesis genes and alters membrane composition. J Bacteriol 187:2357–2367. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2357-2367.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szurmant H, Nelson K, Kim E-J, Perego M, Hoch JA. 2005. YycH regulates the activity of the essential YycFG two-component system in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 187:5419–5426. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5419-5426.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szurmant H, Mohan MA, Imus PM, Hoch JA. 2007. YycH and YycI interact to regulate the essential YycFG two-component system in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 189:3280–3289. doi: 10.1128/JB.01936-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.James BW, Mauchline WS, Dennis PJ, Keevil CW, Wait R. 1999. Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate in Legionella pneumophila, an energy source for survival in low-nutrient environments. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:822–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.López C, Heras H, Garda H, Ruzal S, Sánchez-Rivas C, Rivas E. 2000. Biochemical and biophysical studies of Bacillus subtilis envelopes under hyperosmotic stress. Int J Food Microbiol 55:137–142. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.López CS, Heras H, Ruzal SM, Sánchez-Rivas C, Rivas EA. 1998. Variations of the envelope composition of Bacillus subtilis during growth in hyperosmotic medium. Curr Microbiol 36:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s002849900279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lusk JE, Kennedy EP. 1972. Altered phospholipid metabolism in a sodium-sensitive mutant of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 109:1034–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohniwa RL, Kitabayashi K, Morikawa K. 2013. Alternative cardiolipin synthase Cls1 compensates for stalled Cls2 function in Staphylococcus aureus under conditions of acute acid stress. FEMS Microbiol Lett 338:141–146. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Annous BA, Becker LA, Bayles DO, Labeda DP, Wilkinson BJ. 1997. Critical role of anteiso-C15:0 fatty acid in the growth of Listeria monocytogenes at low temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:3887–3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sampathkumar B, Khachatourians GG, Korber DR. 2004. Treatment of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis with a sublethal concentration of trisodium phosphate or alkaline pH induces thermotolerance. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:4613–4620. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4613-4620.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Álvarez-Ordóñez A, Fernández A, López M, Arenas R, Bernardo A. 2008. Modifications in membrane fatty acid composition of Salmonella typhimurium in response to growth conditions and their effect on heat resistance. Int J Food Microbiol 123:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martinez-Bueno MA, Tobes R, Rey M, Ramos JL. 2002. Detection of multiple extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors in the genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 and their counterparts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01. Environ Microbiol 4:842–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]