Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening rates are low among vulnerable populations. Fecal immunochemical tests (FITs) are one screening modality with few barriers. Studies have shown that outreach can improve CRC screening, but little is known about its effectiveness among individuals with no CRC screening history. We sought to determine whether outreach increases FIT uptake among patients with no CRC screening history compared to usual care.

METHODS

This study was a patient-level randomized controlled trial, including 420 patients who had never completed CRC screening and were eligible for FIT; 66 % were female, 62.1 % were Latino, and 70.7 % were uninsured. The main outcome measure was FIT completion within 6 months of the randomization date. We assessed FIT completion at different time points corresponding to receipt of outreach components. All analyses were re-run with 12-month data.

RESULTS

Patients who received outreach were more likely to complete FIT than those in usual care (36.7 % vs. 14.8 %; p < 0.001). FIT completion was more common among patients with increased clinic visits. The difference in FIT completion between the outreach and usual care groups decreased over time.

DISCUSSION

The intervention improved FIT uptake among patients with no CRC screening history. However, the intervention was less effective than in a previous trial targeting patients due for repeat screening. Additional research is needed to determine the best methods for improving CRC screening among this hard-to-reach group.

KEY WORDS: health disparities, cancer prevention, care delivery system

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, only 65.1 % of adults in the United States aged 50–75 years were up to date on colorectal cancer (CRC) screening.1 Screening rates were lower among minorities and individuals with low income, limited education, no health insurance, or unreliable access to healthcare.1 The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening by annual fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), sigmoidoscopy every 5 years plus FOBT every 3 years, or colonoscopy every 10 years. Colonoscopy is the most common CRC screening modality.1–4 However, its effectiveness for reducing CRC mortality for vulnerable populations is unclear, given the barriers to colonoscopy, including cost, transportation problems, preparing for the procedure, and fear of invasive tests.5–12 Expanded use of FOBT, a modality with fewer barriers, may be a viable approach to address CRC screening disparities, especially with single-sample fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), which do not require dietary restrictions.13

Several randomized trials have reported that outreach with FOBT can improve CRC screening rates.14–20 However, most were conducted in integrated health plans.15, 16, 18, 19 Few targeted vulnerable populations cared for in community health centers (CHCs) and other safety net settings.21–24 We previously reported that a multifaceted outreach and reminder intervention using mailed FITs increased adherence to annual screening, compared to point-of-care strategies that maximize FIT distribution at clinic visits, for patients due for repeat screening.20 However, this study did not examine the impact of outreach for patients who had never been screened before.

A study by Gupta and colleagues targeted uninsured patients in a safety net setting who were due for CRC screening and assessed the efficacy of outreach, using a mailed FIT or letter offering to arrange colonoscopy, compared to usual care.17 Patients randomized to FIT outreach had higher screening rates than those who received the colonoscopy letter or usual care (40.7, 24.6, and 12.1 %, respectively). Despite its importance, this study had several limitations. First, clinics did not establish point-of-care strategies for improving CRC screening, such as electronic health record (EHR) reminders to providers or empowerment of non-clinician staff to distribute FOBTs. Thus, the difference between the FIT outreach and usual care groups may overestimate the value of outreach compared to other evidence-based strategies.25 Additionally, patients in the usual care group received a three-sample guaiac-based FOBT (gFOBT), while the intervention group received a FIT. Completion rates are higher with FIT than gFOBT,26, 27 preventing us from separating the effect of outreach from FIT usage. Finally, this study did not stratify patients by prior screening behaviors, despite the fact that never-screened patients may have lower knowledge about CRC screening, tend to rely on physician recommendations, and have negative attitudes toward FOBT.28–33

To address gaps in the evidence base, we conducted this study to determine the marginal effect of outreach (mailed FIT, reminders, and personal calls), compared to high-quality point-of-care strategies, on CRC screening among CHC patients with no screening history. Understanding the benefits of outreach over point-of-care strategies is important because of the resources required for outreach.

METHODS

This study used similar methodology to a previous randomized controlled trial that sought to increase adherence to annual FOBT among individuals who were due for repeat CRC screening. In that trial, 82.2 % of individuals who received the intervention completed a repeat FOBT within 6 months of their due date compared to 37.3 % of those in usual care.20 The outreach intervention for this study and materials have been published previously.34 This study was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent for patient randomization.

Study Setting

The study was conducted at Erie Family Health Center (EFHC), a federally qualified health center network based in Chicago, Illinois with eight clinics serving adult patients. At EFHC, 55 % of patients are best served in Spanish, 95 % fall below 200 % of the federal poverty line, and 35 % are uninsured. EFHC uses the General Electric Centricity EHR for all clinical encounters, which has healthcare reminders and decision support tools, including reminders for CRC screening. Prior to this study, EFHC initiated a strategic plan to improve CRC screening for eligible patients, including: 1) empowering medical assistants to identify patients due for screening, counsel them, and give them a FOBT; 2) giving providers routine quality measurement and feedback on CRC screening rates; and 3) including CRC screening as a quality metric for providers’ incentive compensation formula. Since these improvements, the proportion of patients up-to-date on CRC screening increased from 17 % in 2007 to 43 % in 2009.34 These strategies were sustained throughout this study for all patients.

Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible patients were 50–75 years old, had a preferred language of English or Spanish, at least two EFHC visits over 2 years before the study, and no documentation of CRC screening. We excluded patients with conditions suggesting FOBT may be inappropriate (e.g., chronic diarrhea, inflammatory bowel disease, iron deficiency, metastatic cancer, and previous total colectomy), and those who had a pending or completed referral for colonoscopy, completed FIT, or precluding diagnosis.

Sample Size

Because of EFHC’s strategies to encourage CRC screening with FIT, we assumed that 30 % of the usual care group would complete a FIT within 1 year. We powered the study to detect a 20 % difference in the outreach group, assuming that providers would want to see at least this much increase to justify sustaining outreach programs. To detect this difference with an alpha of 0.05 and 80 % power, we would need at least 103 patients in each group. Because preliminary results in our previous study suggested the intervention was less effective for English-speaking patients, we included 210 Spanish-speaking patients and 210 English-speaking patients so we would have the power to detect the desired effect size in both language groups.

Identification of Eligible Patients and Randomization

An EFHC programmer queried the EHR to identify eligible patients and collect analytic variables. We collected data on demographics, chronic medical conditions, and clinic visits. Over a 7-week period from February through April 2013, a weekly sample of 60 patients (30 English- and 30 Spanish-speakers) was randomized to the outreach or usual care groups. We continued randomization until reaching the target sample size of 420, excluding those who were previously enrolled in the study, as well as those with a non-unique address or phone number.

Intervention

The intervention design was based on a framework of reasons for failure to adhere to annual FOBT; a full description of the framework and the intervention components to address each obstacle was published previously.34

All FOBT screening was conducted using the Polymedco OC-Light Fecal Occult Blood Test, a FIT that detects human hemoglobin in feces in concentrations as low as 0.05 micrograms/mL.35 It is a single-specimen test with no dietary restrictions. The reported sensitivity and specificity of the OC-Light for detecting CRC are 91.0 and 93.8 %, respectively.36

Each week, patients randomized to the outreach group had FIT kits mailed to their homes, including provider letters and plain language FIT instructions.34 A few days after the mailing, we sent an automated phone call, and 2 days later, a text message via a contracted commercial system (CallPointe; Tuscon, AZ). After 2 weeks, we queried the EHR to identify patients who had not completed a FIT and sent those individuals another automated phone call and text message. Three months after the mailing, we identified patients who had not completed a FIT, and EFHC’s CRC Screening Navigator contacted them by phone. Patients who verbalized willingness to complete the FIT were mailed another kit.

The central EFHC laboratory processed all returned FITs and entered test results into the EHR. If a FIT was negative, the Navigator mailed a letter with the test result and a reminder to repeat the test in 1 year. If the FIT was positive, the Navigator worked with patients’ providers to arrange diagnostic colonoscopy.

Outcome Assessment and Analysis

Final analyses were conducted using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station TX). As in our previous trial, the pre-specified primary outcome was a binary indicator of FIT completion within 6 months of study entry.20 At EFHC, screening colonoscopy is not available to most patients, and FIT testing is the primary screening test recommended. So we used FIT completion alone as our primary outcome, rather than completion of any CRC screening. We assessed completion of CRC screening by querying EHR data, an approach conceptually similar to blinded outcome assessment. Screening completion in the outreach and usual care groups was compared using a chi-square test. We also analyzed differences in the rate of FIT completion at different time points corresponding to receipt of outreach components (0–2 weeks; >2–13 weeks; >13–26 weeks). We conducted predefined subgroup analyses investigating whether intervention effects varied by number of clinic visits during follow-up (0, 1, 2 or more) and language (English vs. Spanish), using multivariable regression models that adjusted for covariates and included interactions. The analyses were repeated with 12-month data.

During our final outcome assessment, we identified eight patients who had a colonoscopy before study randomization. However, procedure results were entered into the EHR after randomization. We conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding these individuals; the results were virtually identical to our main analysis, so the results are not reported.

We also examined the intervention’s fidelity, including the proportion of patients who did not receive the initial mailing (i.e., returned to sender), the proportion that received an automated call, and the proportion that received at least one text message. We tested for bivariate associations between receipt of outreach components and FIT completion using chi-square tests. Receiving the automated call was classified as: 1) answered in person one or more times; 2) answered by voicemail, but not in person; or 3) not completed on either of two attempts. We used a two-sided p value of 0.05 to determine statistical significance for all analyses.

RESULTS

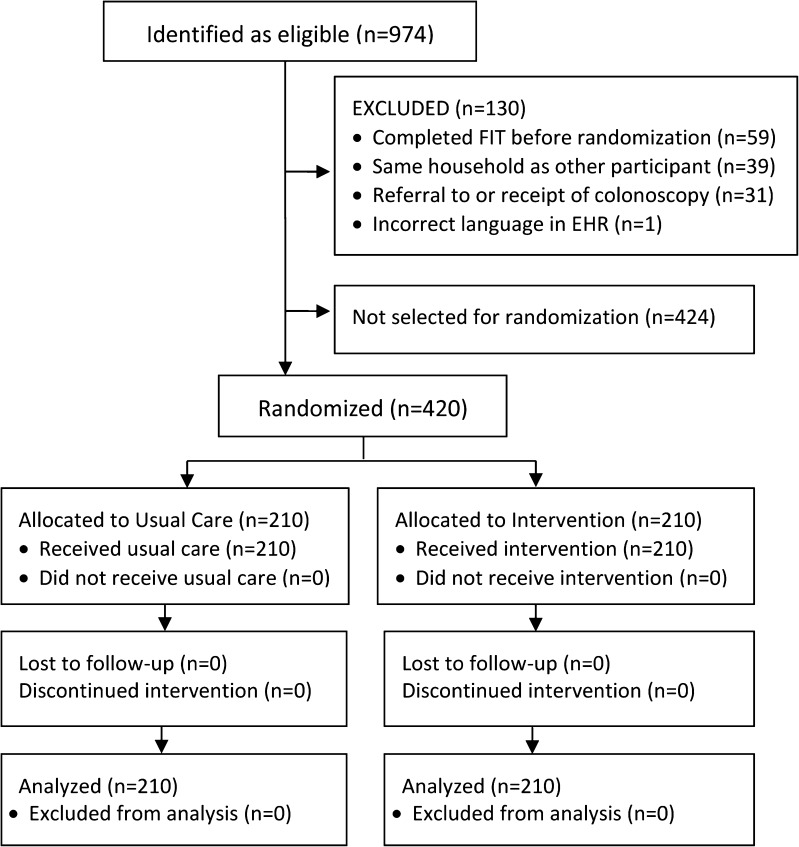

A total of 974 patients were eligible for study enrollment, based on having no CRC screening history, being due for screening, and having at least two visits in the past 2 years (Fig. 1). Prior to randomization, the Navigator reviewed charts to exclude patients who were ineligible, including: 1) patients who completed FOBT before randomization (n = 59); 2) individuals in the same household as another eligible patient (the second person on the list was excluded, n = 39); 3) patients with pending or completed colonoscopy (n = 31); and 4) patients whose language was incorrect in the EHR (n = 1). Of the remaining 844 patients, 210 (105 Spanish-speaking and 105 English-speaking) were randomized to each group (N = 420).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients randomized to receive usual care or outreach.

In the final sample, patients’ mean age was 57.3 years (SD = 6.2), 66.0 % were female, 62.1 % identified their race/ethnicity as Latino/Hispanic (79.7 % Spanish- and 20.3 % English-speaking), 70.7 % were uninsured, and 74.8 % had one or more chronic medical conditions (Table 1). There were no significant group differences in baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics for the Outreach and Usual Care Groups

| Characteristic | Total (n = 420) | Outreach (n = 210) | Usual Care (n = 210) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 57.3 (6.2) | 57.5 (6.2) | 57.0 (6.2) | 0.43* |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| 50–54 | 181 (43.1) | 85 (40.5) | 96 (45.7) | 0.59† |

| 55–59 | 103 (24.5) | 51 (24.3) | 52 (24.8) | |

| 60–64 | 75 (17.9) | 42 (20.0) | 33 (15.7) | |

| 65–74 | 61 (14.5) | 32 (15.2) | 29 (13.8) | |

| Female, n (%) | 277 (66.0) | 139 (66.2) | 138 (65.7) | 0.92† |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Latino, Spanish speaking | 208 (49.5) | 104 (49.5) | 104 (49.5) | 0.10† |

| Latino, English speaking | 53 (12.6) | 24 (11.4) | 29 (13.8) | |

| White | 66 (15.7) | 28 (13.3) | 38 (18.1) | |

| Black | 69 (16.4) | 44 (21.0) | 25 (11.9) | |

| Other | 24 (5.7) | 10 (4.8) | 14 (6.7) | |

| Insurance status, n (%) | ||||

| Uninsured | 297 (70.7) | 145 (69.1) | 152 (72.4) | 0.30§ |

| Medicaid | 58 (13.8) | 31 (14.8) | 27 (12.9) | |

| Medicare | 48 (11.4) | 22 (10.5) | 26 (12.4) | |

| Commercial | 17 (4.1) | 12 (5.7) | 5 (2.4) | |

| Chronic medical conditions, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 106 (25.2) | 50 (23.8) | 56 (26.7) | 0.69† |

| 1 | 164 (39.1) | 86 (41.0) | 78 (37.1) | |

| 2 or more | 150 (35.7) | 74 (35.2) | 76 (36.2) | |

* T-test, continuous variables

† Chi-square, categorical variables

§ Fisher’s exact, categorical variables (cell size ≤ 5)

Over the first 6 months of follow-up, 77 (36.7 %) patients in the outreach group and 31 (14.8 %) in the usual care group completed a FIT (p < 0.001; Table 2). In addition, one patient (0.5 %) in the usual care group underwent colonoscopy. Thus, 15.2 % of the usual care group completed CRC screening within 6 months (p < 0.001; Table 2). In the 2 weeks after the mailing and outreach, 29 (13.8 %) patients in the outreach group completed a FIT. Between 2 and 13 weeks after outreach, an additional 29 (13.8 %) outreach patients completed a FIT. Nineteen (9.1 %) outreach patients completed a FIT between weeks 13 and 26. During each time period over the first 6 months of follow-up, the rate of FIT completion was higher for the outreach group compared to the usual care group (Table 2). However, the difference between the outreach and usual care groups between weeks 13 and 26 was small (9.1 % vs. 7.1 %, respectively).

Table 2.

Completion of CRC Screening by Time from Date of Randomization

| Patients, No. (%) | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FOBT completed, week | Outreach (n = 210) | Usual Care (n = 210) | |

| 0–2 | 29 (13.8) | 6 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| > 2–13 | 29 (13.8) | 10 (4.8) | 0.001 |

| > 13–26 | 19 (9.1) | 15 (7.1) | 0.47 |

| > 26–52 | 7 (3.3) | 16 (7.6) | 0.05 |

| Total FOBT completed, months | |||

| 6 months† | 77 (36.7) | 31 (14.8) | p < 0.001 |

| 12 months | 84 (40.0) | 47 (22.4) | p < 0.001 |

| Total CRC screening, months§ | |||

| 6 months | 77 (36.7) | 32 (15.2) | p < 0.001 |

| 12 months | 84 (40.0) | 49 (23.3) | p < 0.001 |

* Chi-square tests for group-level differences in outcomes

† Primary study outcome

§ One additional usual care patient completed screening colonoscopy within 6 months and two additional usual care patients completed screening colonoscopy within 1 year

The group difference in FIT completion rates changed slightly over time. At 12 months of follow-up, 84 (40.0 %) patients in the outreach group and 47 (22.4 %) in the usual care group completed a FIT (p < 0.001; Table 2). Between 26 and 52 weeks after randomization, seven (3.3 %) patients in the outreach group and 16 (7.6 %) in the usual care group completed a FIT. One additional patient (0.5 %) in the usual care group underwent colonoscopy between 6 and 12 months. Thus, 23.3 % of patients in the usual care group completed CRC screening within 12 months of their randomization date.

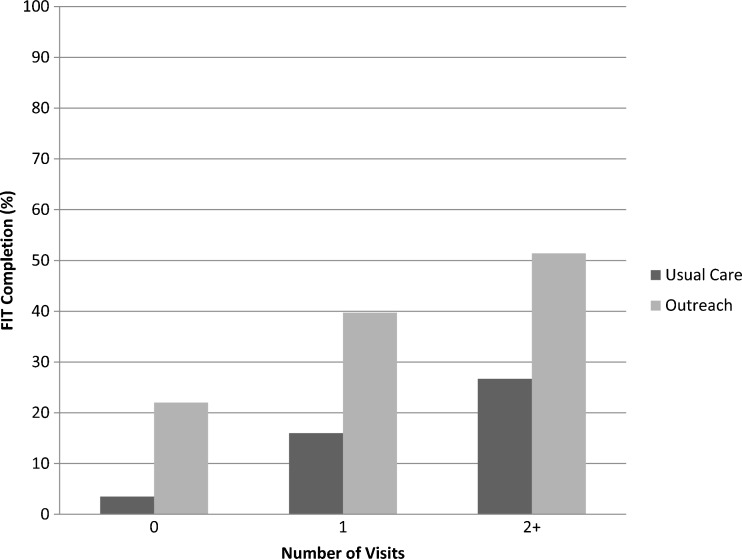

FIT completion was more common for patients with more clinic visits (Fig. 2; p < 0.001 for within-group chi-square tests). There was no difference in completion rates by language. The difference in FIT completion was similar at 12 months of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Effect of number of visits over 6 months on completion of FOBT.

The number of outreach patients who received each intervention component (i.e., mailing, automated call, text message, and 3-month call from the Navigator) is presented in Table 3. Of the mailings, 32 (15.2 %) had an incorrect address and were returned to sender. Most automated calls were answered in person (53.8 %) or by voicemail (34.8 %). The FIT completion rate within 13 weeks of randomization was similar among those who answered one or more calls in person (31.9 %) or by voicemail (28.8 %; p = 0.66). Patients who answered an automated call in person were more likely to complete a FIT within 13 weeks than those without a completed automated call (31.9 % vs. 4.2 %; p = 0.006). The text message was completed one or more times for 78.1 % of patients. Those who received a text message were more likely to complete a FIT than patients who did not receive one (32.3 % vs. 10.9 %; p = 0.004). After 13 weeks, the Navigator attempted to contact all 152 patients who had not yet completed a FIT, and spoke with 79 (52.0 %) of them. Those reached by the Navigator completed FIT more often between weeks 13–26 than those who were not reached (16.5 % vs. 8.2 %, respectively), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.13).

Table 3.

Receipt of Intervention Components and Relationship to Completion of FOBT

| Total (Column %) | FOBT Completed (Row %) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outreach (N = 210): Components Received and FOBT Completed Within 13 Weeks of Randomization | |||

| Mailing | |||

| Not returned | 178 (84.8) | 53 (29.8) | 0.10 |

| Returned | 32 (15.2) | 5 (15.6) | |

| Automated call | |||

| Answered in person | 113 (53.8) | 36 (31.9) | REF |

| Answered by voicemail | 73 (34.8) | 21 (28.8) | 0.66 |

| Not completed | 24 (11.4) | 1 (4.2) | 0.006 |

| Text message | |||

| Completed | 164 (78.1) | 53 (32.3) | 0.004 |

| Not completed | 46 (21.9) | 5 (10.9) | |

| Three-Month Call (n = 152): Component Received and FOBT Completed Between 13 and 26 Weeks | |||

| Spoke with patient by telephone | 79 (52.0) | 13 (16.5) | 0.13 |

| Unable to reach patient | 73 (48.0) | 6 (8.2) | |

*All p values are for pairwise chi-square tests. For analyses of the subgroups for the outcomes of the automated call, the p values are for pairwise chi-square tests between the category listed and the reference group (REF)

Five of 77 (6.5 %) patients in the outreach group who completed a FIT within 6 months had a positive result. By the end of the study, three (60.0 %) had completed a diagnostic colonoscopy, one (20.0 %) was scheduling the procedure, and one (20.0 %) had refused. Among the 31 patients in the usual care group who completed a FIT within 6 months, five (16.1 %) had a positive result (p = 0.12 vs. outreach group); of these, three (60.0 %) were in the process of scheduling diagnostic colonoscopy and two (40.0 %) had refused.

DISCUSSION

The multifaceted outreach intervention substantially improved FIT completion among individuals who had never completed CRC screening previously. The majority of those who received outreach completed a FIT within 3 months, after the mailing and automated calls and texts, but before the Navigator’s personal reminder calls. Given that the success rate for the Navigator calls was low (only 19 of 152 (12.5 %) patients targeted completed a FIT in the subsequent 3 months), our results suggest the benefits of outreach can be largely realized through simple methods that leverage EHR data. EHRs are now used by the majority of CHCs in the U.S.,13 and most have the ability to deliver the automated elements of the outreach intervention under study here.

Unlike previous studies, ours occurred in a CHC with established point-of-care strategies to improve CRC screening, including performance feedback, financial incentives, and use of FIT. This may explain why our usual care group FIT completion rate was higher than other studies. Gupta and colleagues reported a 12.1 % completion rate at 12 months in their usual care group, which included patients previously screened,17 whereas we found a 14.8 % rate at 6 months and a 22.4 % rate at 12 months. Nevertheless, the completion rate in our usual care group was low, even among patients with two or more CHC visits (26.7 %), demonstrating the limitations of point-of-care strategies in CHCs that care for vulnerable populations.

Although our intervention substantially increased FIT completion compared to usual care, the absolute rate of FIT completion and the marginal benefit of outreach were less than in our previous trial to promote adherence to repeat screening (37.3 % vs. 82.2 % respectively).20 The low completion rate may be due to the different study sample. Unlike previous studies, we only included patients with no screening history; however, many patients may have been offered CRC screening before, but not completed it. The idea that this is a resistant group is supported by the fact that between 6 and 12 months, the screening rate among the outreach group increased only slightly from 36.7 to 40.0 %, suggesting there may be an upper limit to the proportion of patients who are willing to complete CRC screening. Previous research supports the importance of provider recommendations for CRC screening, and patients who have never completed CRC screening may need provider counseling before completing a FIT.30, 33, 37–39

Our study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single organization with a somewhat homogenous population and few clinical sites. EFHC is well respected and patients’ trust in the organization may be greater than other CHCs. In addition, the EFHC patient population may have a higher proportion of patients with valid addresses and/or working telephones than other underserved populations. Second, although we restricted the sample to patients with no previous CRC screening, it is likely that some patients had been screened prior to getting care at EFHC, but did not have this recorded in the EHR. Thus, our completion rates may overestimate the true rate for a group that had never been screened. Third, our sample was relatively small. Although we found no differences in the intervention’s effect by demographics, chronic conditions, or number of visits, our power to detect differences was small. Finally, we did not interview patients to determine their reactions to outreach and reasons for not completing a FIT.

Our results provide the best estimate to date of the marginal value of outreach compared to point-of-care strategies alone for patients who have not previously completed CRC screening. Due to the lower effectiveness of outreach among patients who have never completed CRC screening (versus patients due for repeat annual FOBT),20 providers may decide that it is efficient to use point-of-care approaches to encourage initial FOBT, while using outreach to promote adherence to repeat screening. Future cost–benefit analyses are needed to determine the most successful and efficient strategies to initiate CRC screening for vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, grant number 1P01HS021141-01.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and are not an official position of the institution or funder.

Source of Support

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 1P01HS021141-01.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use—United States, 2012. MMWR. 2013;62(44):881–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liss DT, Baker DW. Understanding current racial/ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening in the United States: the contribution of socioeconomic status and access to care. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3):228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joseph DA, King JB, Miller JW, Richardson LC. Prevalence of colorectal cancer screening among adults--Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(Suppl):51–6. [PubMed]

- 4.Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, Thompson TD, Nadel MR, Seeff LC, White A. Patterns of colorectal cancer test use, including CT colonography, in the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(6):895–904. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zauber AG,7 Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Wilschut J, van Ballegooijen M, Kuntz KM. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):659–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Thomas JP, Lin YV, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):575–82. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalid-de Bakker C, Jonkers D, Smits K, Mesters I, Masclee A, Stockbrugger R. Participation in colorectal cancer screening trials after first-time invitation: a systematic review. Endoscopy. 2011;43(12):1059–86. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLachlan SA, Clements A, Austoker J. Patients’ experiences and reported barriers to colonoscopy in the screening context–a systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ Counsel. 2012;86(2):137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sly JR, Edwards T, Shelton RC, Jandorf L. Identifying barriers to colonoscopy screening for nonadherent African American participants in a patient navigation intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):449–57. doi: 10.1177/1090198112459514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doubeni CA, Jambaulikar GD, Fouayzi H, Robinson SB, Gunter MJ, Field TS, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and use of colonoscopy in an insured population–a retrospective cohort study. PloS One. 2012;7(5):e36392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jandorf L, Ellison J, Villagra C, Winkel G, Varela A, Quintero-Canetti Z, et al. Understanding the barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening among low income immigrant hispanics. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2010;12(4):462–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9274-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shokar NK, Carlson CA, Weller SC. Factors associated with racial/ethnic differences in colorectal cancer screening. JABFM . 2008;21(5):414–26. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin P, Sharac J. Readiness for meaningful use of health information technology and patient centered medical home recognition survey results. Medicare & medicaid research review. 2013;3(4). doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.04.b01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Davis TC, Arnold CL, Bennett CL, Wolf MS, Reynolds C, Liu D, et al. Strategies to improve repeat fecal occult blood testing cancer screening. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(1):134–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coronado GD, Golovaty I, Longton G, Levy L, Jimenez R. Effectiveness of a clinic-based colorectal cancer screening promotion program for underserved Hispanics. Cancer. 2011;117(8):1745–54. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green BB, Wang CY, Anderson ML, Chubak J, Meenan RT, Vernon SW, et al. An automated intervention with stepped increases in support to increase uptake of colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5):301–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta S, Halm EA, Rockey DC, Hammons M, Koch M, Carter E, et al. Comparative effectiveness of fecal immunochemical test outreach, colonoscopy outreach, and usual care for boosting colorectal cancer screening among the underserved: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempe KL, Shetterly SM, France EK, Levin TR. Automated phone and mail population outreach to promote colorectal cancer screening. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(7):370–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin TR, Jamieson L, Burley DA, Reyes J, Oehrli M, Caldwell C. Organized colorectal cancer screening in integrated health care systems. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33(1):101–10. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, Weil J, Balsley K, Ranalli L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to annual colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darnell JS. Free clinics in the United States: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(11):946–53. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Politzer RM, Yoon J, Shi L, Hughes RG, Regan J, Gaston MH. Inequality in America: the contribution of health centers in reducing and eliminating disparities in access to care. Med Care Res Rev. 2001;58(2):234–48. doi: 10.1177/107755870105800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dievler A, Giovannini T. Community health centers: promise and performance. Med Care Res Rev. 1998;55(4):405–31. doi: 10.1177/107755879805500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Primary Health Care. Health Centers: America’s Primary Care Safety Net, Reflections on Success, 2002–2007. Rockville, MD: 2008.

- 25.Holden DJ, Jonas DE, Porterfield DS, Reuland D, Harris R. Systematic review: enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(10):668–76. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hol L, van Leerdam ME, van Ballegooijen M, van Vuuren AJ, van Dekken H, Reijerink JC, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: randomised trial comparing guaiac-based and immunochemical faecal occult blood testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gut. 2010;59(1):62–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.177089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassan C, Giorgi Rossi P, Camilloni L, Rex DK, Jimenez-Cendales B, Ferroni E, et al. Meta-analysis: adherence to colorectal cancer screening and the detection rate for advanced neoplasia, according to the type of screening test. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2012;36(10):929–40. doi: 10.1111/apt.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanley S, King J, Thomas C, Richardson L. Factors associated with never being screened for colorectal cancer. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):31–9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bynum SA, Davis JL, Green BL, Katz RV. Unwillingness to participate in colorectal cancer screening: examining fears, attitudes, and medical mistrust in an ethnically diverse sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(5):295–300. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110113-QUAN-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bass SB, Gordon TF, Ruzek SB, Wolak C, Ward S, Paranjape A, et al. Perceptions of colorectal cancer screening in urban African American clinic patients: differences by gender and screening status. J Canc Educ. 2011;26(1):121–8. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0123-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cokkinides VE, Chao A, Smith RA, Vernon SW, Thun MJ. Correlates of underutilization of colorectal cancer screening among U.S. adults, age 50 years and older. Prev Med. 2003;36(1):85–91. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma GX, Wang MQ, Toubbeh J, Tan Y, Shive S, Wu D. Factors associated with colorectal cancer screening among Cambodians, Vietnamese, Koreans and Chinese living in the United States. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;5(1):1. doi: 10.7156/v5i1p001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS. Factors associated with colon cancer screening: the role of patient factors and physician counseling. Prev Med. 2005;41(1):23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, Weil J, Cameron KA, Ranalli L, et al. Design of a randomized controlled trial to assess the comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to colorectal cancer screening among patients cared for in a community health center. BMC health services research. 2013;13(1):153. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polymedco. The preferred screening method for patients [cited May 16, 2011]. Available from: http://polymeedco.com/product-overview-pages-61.php.

- 36.Lohsiriwat V, Thavichaigarn P, Awapittaya B. A multicenter prospective study of immunochemical fecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer detection. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet. 2007;90(11):2291–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert A, Kanarek N. Colorectal cancer screening: physician recommendation is influential advice to Marylanders. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):367–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameron KA, Francis L, Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Investigating Hispanic/Latino perceptions about colorectal cancer screening: a community-based approach to effective message design. Patient Educ Counsel. 2007;68(2):145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naylor K, Ward J, Polite BN. Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J Gen Int Med. 2012;27(8):1033–46. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2044-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]