CASE

A 33-year-old woman with a history of prior valve replacement for infective endocarditis secondary to intravenous drug use presented with altered mental status. CT head showed acute cerebellar and occipital lobe hemorrhages requiring emergent evacuation. Postoperatively, she was noted to have cutaneous lesions in her nail beds and palms that were typical for splinter hemorrhages associated with endocarditis (Fig. 1), painful lesions consistent with Osler nodes and painless Janeway lesions (Fig. 2). A transesophageal echocardiogram revealed an intracardiac abscess around the aortic root. Given her recent intracranial bleed, she was not considered a surgical candidate for repeat cardiac intervention and was discharged with hospice care, consistent with her wishes.

Figure 1.

Splinter hemorrhages (black arrow) seen in the distal nail bed.

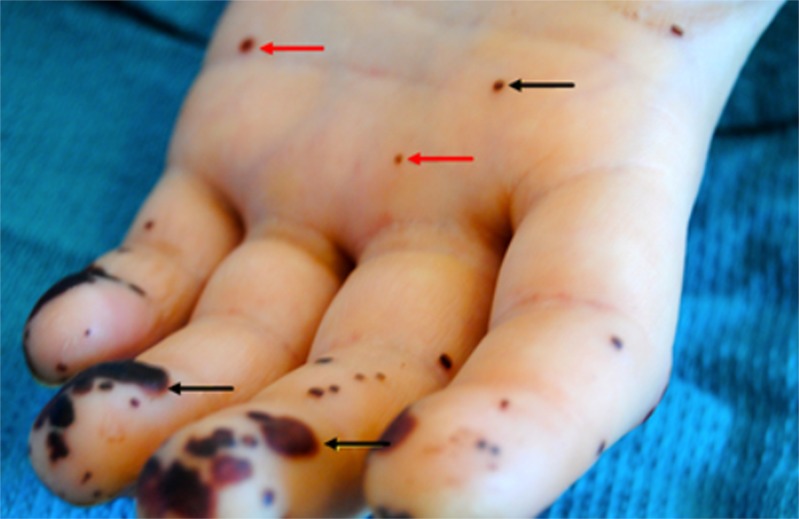

Figure 2.

Osler nodes (black arrow) seen in the palm of the left hand, and Janeway lesions (red arrow) seen on the finger pulp and palm of the left hand.

Cutaneous manifestations of infective endocarditis, a commonly reported phenomenon in the pre-antibiotic era,1 are rare in the present times.2 Osler’s nodes are typically painful lesions that occur on fingers and toes and are attributed to an immune-mediated response. In contrast, splinter hemorrhages (involving the distal nail bed) and Janeway lesions (involving the palms and soles) are painless and secondary to septic microemboli.3 Early recognition of these clinical signs is important as they indicate the presence of systemic embolization and are associated with poor outcomes.4

Acknowledgments

There are no funding sources, internal or external.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

All authors have had access to all data in the study, read and approved submission of the letter, and the findings have not been presented previously in any conference or published in print or electronic format.

References

- 1.Yee J, McAllister CK. Osler’s nodes and the recognition of infective endocarditis: a lesion of diagnostic importance. South Med J. 2013;1987:753–7. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198706000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med. 2013;2009:463–73. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman ME, Upshaw CB., Jr Extracardiac manifestations of infective endocarditis and their historical descriptions. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(12):1802–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Servy A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Alla F, Lechiche C, Nazeyrollas P, Chidiac C, Hoen B, Chosidow O, Duval X. Association Pour l’Etude et la Prévention de l’Endocardite Infectieuse Study Group. Prognostic value of skin manifestations of infective endocarditis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(5):494–500. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]