Abstract

An involvement of the immune system has been suggested in Rett syndrome (RTT), a devastating neurodevelopmental disorder related to oxidative stress, and caused by a mutation in the methyl-CpG binding protein 2 gene (MECP2) or, more rarely, cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5). To date, it is unclear whether both mutations may have an impact on the circulating cytokine patterns. In the present study, cytokines involved in the Th1-, Th2-, and T regulatory (T-reg) response, as well as chemokines, were investigated in MECP2- (MECP2-RTT) (n = 16) and CDKL5-Rett syndrome (CDKL5-RTT) (n = 8), before and after ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) supplementation. A major cytokine dysregulation was evidenced in untreated RTT patients. In MECP2-RTT, a Th2-shifted balance was evidenced, whereas in CDKL5-RTT both Th1- and Th2-related cytokines (except for IL-4) were upregulated. In MECP2-RTT, decreased levels of IL-22 were observed, whereas increased IL-22 and T-reg cytokine levels were evidenced in CDKL5-RTT. Chemokines were unchanged. The cytokine dysregulation was proportional to clinical severity, inflammatory status, and redox imbalance. Omega-3 PUFAs partially counterbalanced cytokine changes, as well as aberrant redox homeostasis and the inflammatory status. RTT is associated with a subclinical immune dysregulation as the likely consequence of a defective inflammation regulatory signaling system.

1. Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) (OMIM ID: 312750) is a severe progressive neurological disorder usually linked to two major X-linked gene mutations, that is, methyl-CpG binding protein 2 gene (MECP2) and cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5) [1–3].

MECP2 mutations are known to cause up to 90–95% of cases with typical clinical presentation (MECP2-RTT) which include early neurological regression followed by loss of acquired cognitive, social, and motor skills in a typical 4-stage neurological regression, together with development of autistic behavior [4]. The typical disease, manifesting above 6–18 months almost exclusively in girls, represents the second most common cause of severe intellective disorder in the female gender [1] and its frequency is approximatively 1 : 10,000 with a random worldwide distribution [5]. MECP2 mutations have also been reported in a milder syndrome phenotype (i.e., preserved speech variant), as well as other non-RTT disorders, such as Angelman syndrome, mild learning disability in females, neonatal encephalopathy (largely predominant in males), and X-linked intellectual disability [6].

Although MeCP2 has been extensively studied in the central nervous system [7], MeCP2 is a ubiquitous nuclear protein [8]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which MeCP2 deficiency drives pathology in RTT remain elusive. MeCP2 is currently considered a multifunctional regulator of gene transcription, involved in RNA splicing and chromatin remodelling [7]. A close biochemical and genetic relationship exists between MeCP2 and CDKL5 in that the encoded CDKL5 protein is known to be a kinase able to mediate MeCP2 phosphorylation [3] and that CDKL5 has been reported to be a MeCP2-repressed target gene [9]. CDKL5-related RTT (CDKL5-RTT) is known as the early-onset seizures variant (ESV) and is associated with severe early-onset seizures and partially different clinical RTT-like features [10], so that recently the CDKL5 disorder has been proposed as an independent clinical entity rather than an additional RTT variant [11].

Our prior studies indicate that (1) MeCP2 is involved—either directly or indirectly—in the regulation of the redox balance in RTT [12–18]; (2) a direct evidence of the link between MeCP2 deficiency, oxidative stress (OS), and RTT pathology exists in murine models of the disease [18]; (3) a redox imbalance has also been evidenced in CDKL5-RTT [16]. Proofs for a direct relationship between the MeCP2 protein and OS are lacking to date. However, we have previously demonstrated that OS in brains of mouse with Mecp2 loss-of-function mutations precedes and accompanies symptoms of the disease and is rescued by selective Mecp2 gene reexpression [18]. Whether mitochondria are the main, or the only, major intracellular source for abnormal redox status in RTT [19–23] or other “MECP2-pathies” is still to be ascertained, given that no major morphological alterations in mitochondria have been evidenced by our group at the transmission electron microscopy of primary cultures of skin fibroblasts from MECP2-RTT, whereas major changes were observed in the endoplasmic reticulum, along with cytoplasmic multilamellar bodies [17].

MECP2-RTT appears to be intimately related to inflammation [24, 25]. There is prior evidence that MeCP2 associates with CpG elements of the regulatory regions of Foxp3 gene, a known transcription factor needed for the generation of T regulatory (T-reg) cells [26]. This observation supports the concept that MeCP2 could play a regulatory role in T cells' resilience to inflammation [27]. Furthermore, a very recent report demonstrates that MeCP2 acts as a regulator of the response to inflammatory stimuli in the microglia and macrophages of Mecp2-null mice [28].

While an impact on the immune system in gain-of-function mutations, such as the MECP2 duplication syndrome is evidenced [29, 30], no clinically relevant primary immune deficiency has been previously reported in either MECP2-RTT or CDKL5-RTT. Nevertheless, an involvement of the immune system in MECP2-RTT has been previously suggested [31–35] although conflicting negative evidence also exists [36–38].

Preliminary findings by Ariani suggest that a reduced frequency of HLA-B39 is present in MECP2-RTT [39], whose reasons and biological consequences need to be clarified. Some disrupting mutations in chemokines and chemokines receptors have been reported by Grillo et al. in the preserved speech variant of RTT, thus suggesting this combination of mutations along with the MECP2 loss-of-function may modulate the immune system [40].

An association between MECP2 gene polymorphisms and autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (LES) [41, 42] and primary Sjögren's syndrome [43], has been reported. High levels of serum anti-N (Glc) autoantibodies of the IgM fraction have been recently reported in RTT [44]. A direct relationship between MeCP2 and the immune system has been recently evidenced, since MeCP2 has been found to be indispensable for the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th17 cells and for the commitment of naïve CD4+ T cells to the Th1 lineage [30]. Moreover, MeCP2 has been shown to play a critical role in promoting multiple cytokine-mediated signaling pathway through a MeCP2-miR-124-suppressor of cytokine signaling 5 (SOCS5) axis known to be indispensable for the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and STAT1 in CD4+ T cells [30]. This signaling pathway appears to be indispensable for the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (i.e., STAT3) in naïve CD4+ T cells, with consequent generation of Th17 cells [30].

In the present study, we evaluated systemic cytokine patterns, oxidative stress markers, and inflammatory status in both typical MECP2-RTT and CDKL5-RTT as a function of a 12-month supplementation with ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

The study included 24 Rett female patients with different clinical diagnosis: typical Rett syndrome (n = 16, mean age: 14.2 ± 9.5 years, range: 3–39) with demonstrated MECP2 gene mutation and ESV (n = 8, mean age: 8.7 ± 4.8 years, range: 2–17) with demonstrated CDKL5 gene mutation. Rett syndrome diagnosis and inclusion/exclusion criteria were based on the recently revised Rett syndrome nomenclature consensus [45].

Clinical examinations and blood samplings in the MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT patients' groups were performed before and after ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) supplementation during the routine follow-up study at hospital admission. Given the specific aims of this study, patients with clinically evident inflammatory conditions (i.e., upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, urinary infection, stomatitis, and periodontal inflammation), either acute or chronic, were excluded.

None of the patients at the time of enrollment were on anti-inflammatory drugs or undergoing supplementation with other known antioxidants. All the patients were consecutively admitted to the “Rett Syndrome National Reference Centre” (Head Professor J.H.) of the University Hospital of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese (AOUS). The subjects examined in this study were on a typical Mediterranean diet. Rett syndrome clinical severity was assessed using either the total clinical severity score (CSS), a validated clinical rating specifically designed for RTT, or the “compressed” CSS, both based on 13 individual ordinal categories measuring clinical features common in RTT [46]. Healthy female control subjects who have comparable age (n = 24; age: 13.4 ± 4.8 years, range: 2–32) were also included. Blood samplings from the control group were carried out during routine health checks, sports, blood donations, or periodic clinical checks.

The study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the AOUS. All informed consents were obtained from either the parents or the legal tutors of the enrolled patients or directly from healthy adults.

2.2. Omega-3 PUFAs Oral Supplementation

All MECP2- and CDKL5-related RTT patients were supplemented with ω-3 PUFAs oil for 12 months. Administered ω-3 PUFAs were in the form of fish oil before food intake (Norwegian Fish Oil AS, Trondheim, Norway, product number HO320-6; Italian importer: Transforma AS Italia, Forlì, Italy; Italian Ministry registration code: 10 43863-Y) at a dose of 5 mL twice daily, corresponding to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22 : 6 ω-3) 74.3 ± 6.8 mg/kg b.w./day and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20 : 5 ω-3) 119.7 ± 10.6 mg/kg b.w./day, with a total ω-3 PUFAs of 248.2 ± 25.1 mg/kg b.w./day. Use of EPA plus DHA in RTT was approved by the AOUS Ethical Committee. All data obtained in MECP2- and CDKL5-related RTT patients after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation were compared to those obtained before the supplementation.

2.3. Inflammatory Marker

We measured erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) as nonspecific marker of inflammation. ESR was assayed on a widely used automated system (i.e., “TEST 1”) measuring the aggregation capacity of red blood cells (RBCs) by an infrared ray microphotometer with a light wavelength of 950 nm [47].

2.4. Sample Collection

All samplings from RTT patients and healthy controls were carried out around 8 AM after overnight fasting. Blood was collected in heparinized tubes and used for cytokine evaluations and oxidative stress (OS) markers determinations. In particular, blood samples were centrifuged at 2,400 g for 15 min at room temperature. The platelet poor plasma was saved, and the buffy coat was removed by aspiration. RBCs were washed twice with physiological solution, resuspended in Ringer solution (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 32 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, and 1 mM CaCl2), pH 7.4 as a 50% (vol/vol) suspension, and then used for the determination of intraerythrocyte non-protein-bound iron (IE-NPBI). Plasma was used for cytokine, and OS marker (F2-isoprostanes: F2-IsoPs; F2-dihomo-isoprostanes: F2-dihomo-IsoPs; F4-neuroprostanes: F4-NeuroPs, and plasma non-protein-bound iron: P-NPBI) determinations. All manipulations were carried out within 2 h after sample collection. For all isoprostane determinations, butylated hydroxytoluene (90 μM) was added to plasma as an antioxidant and stored under nitrogen at −70°C until analysis.

For serum preparation (IFN-γ and TGF-β1 evaluations), blood samples were left to coagulate for 15–30 min at RT and centrifuged at RT for 10 minutes at 2000 g. Separated sera were kept in aliquots at −80°C until the time of assay.

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for Cytokines

After blood collection, plasma was separated as soon as possible after centrifugation to avoid TNF-α production by blood cells that falsely could increase its values [48]. Levels of T helper type 1- (Th1-) related cytokine response (IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12p70), T helper type 2- (Th2-) related cytokine response (IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, and IL-33), proinflammatory cytokines IL-17A and IL-22, regulatory T (T-reg) cytokine (TGF-β1), and chemokines (IL-8/CXCL8, IP-10/CXCL10, I-TAC/CXCL11, and RANTES/CCL5) were quantified in plasma or serum samples from the examined groups by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), carried out in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Quantikine, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Sera samples were used for IFN-γ and TGF-β1 determinations. The minimum detectable dose (MDD) was 1 pg/mL for IL-1β, 10 pg/mL for IL-4, 0.29 pg/mL for IL-5, 0.70 pg/mL for IL-6, 3.5 pg/mL for IL-8, 3.9 pg/mL for IL-10, 5 pg/mL for IL-12p70, 13.2 pg/mL for IL-13, 15 pg/mL for IL-17A, 2.7 pg/mL for IL-22, 0.519 pg/mL for IL-33, 1.67 pg/mL for IP-10, 13.9 pg/mL for I-TAC, 2.0 pg/mL for RANTES, and 1.6 pg/mL for TNF-α. MDD for IFN-γ and TGF-β1 was 8.0 pg/mL and 4.61 pg/mL, respectively. The levels of plasma IL-37, an anti-inflammatory cytokine recently identified [49], were determined using a commercially available ELISA kit (AdipoGen, Switzerland), according to the manufacturers' instruction. MDD for IL-37 was 10 pg/mL. The samples were performed in duplicate to guarantee the reproducibility of the kits. For reference values, we referred to the reference range as derived from previous reports or, in the lack of prior published results, manufacturer's data sheets. IL-10 is considered as both Th2 cytokine and T-reg cytokine [50].

Th2/Th1 ratio was defined based on the ratio of IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, or IL-10 Th2-related cytokines and proinflammatory IFN-γ and TNF-α Th1-related cytokines [51].

2.6. Redox Status Evaluations

We evaluated the following markers: intraerythrocyte and plasma non-protein-bound iron (IE-NPBI and P-NPBI) (as prooxidant factors) [12], F2-IsoPs (as markers of systemic lipoperoxidation) [12], F2-dihomo-IsoPs (as markers of glia membrane damage/brain white matter) [15], F4-NeuroPs (as markers of neuronal membrane damage/brain gray matter) [14], and blood GSH/GSSG ratio as indicator of antioxidant defence [52].

In particular, P-NPBI and IE-NPBI were determined as a desferrioxamine-iron complex by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [12]. F2-IsoPs, F2-dihomo-IsoPs and F4-NeuroPs (end-oxidation products of arachidonic acid, adrenic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid, resp.) were determined by a gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry (GC/NICI-MS/MS) analysis after solid phase extraction and derivatization steps. For F2-IsoPs, F2-dihomo-IsoPs, and F4-NeuroPs the measured ions were the product ions at m/z 299, 327, and 323, respectively [12–15].

Blood GSH and GSSG levels were determined by an enzymatic recycling procedure according to Tietze et al. [53] and Baker et al. [54].

2.7. Data Analysis

All variables were tested for normal distribution (D'Agostino-Pearson test) and data were presented as mean and standard deviation unless otherwise specified. Statistical analysis for circulating cytokine levels in the groups at baseline and after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation was carried out using Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA test. Bonferroni-corrected significance levels were used for multiple t-tests. Associations between variables were tested by univariate linear regression analysis and multiple regression analyses. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The MedCalc version 12.1.4 statistical software package (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) was used.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Severity in MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT

In the untreated RTT population, mean CCSS for MECP2-RTT and CDKL5-RTT was 7.1 ± 0.6 (values range 5–11) and 4.0 ± 0.5 (values range 7-8), respectively. Major clinical features included neurological regression history (100%), somatic growth deficiency (31.2% MECP2 versus 50% CDKL5), microcephaly (100%), loss of spontaneous ambulation (43.7% MECP2 versus 87.5% CDKL5), loss of purposeful hand use (87.5%), scoliosis (37.5% MECP2-mutated patients), absent verbal language (93.7% MECP2 versus 100% CDKL5), absent nonverbal communication (6.2% MECP2 versus 0% CDKL5), respiratory dysfunction (43.7% MECP2 versus 12.5% CDKL5), autonomic nervous system signs (62.5%), stereotypies (100%), and epilepsy (43.7% MECP2 versus 100% CDKL5).

3.2. Basal Cytokine Patterns in MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT

3.2.1. MECP2- RTT

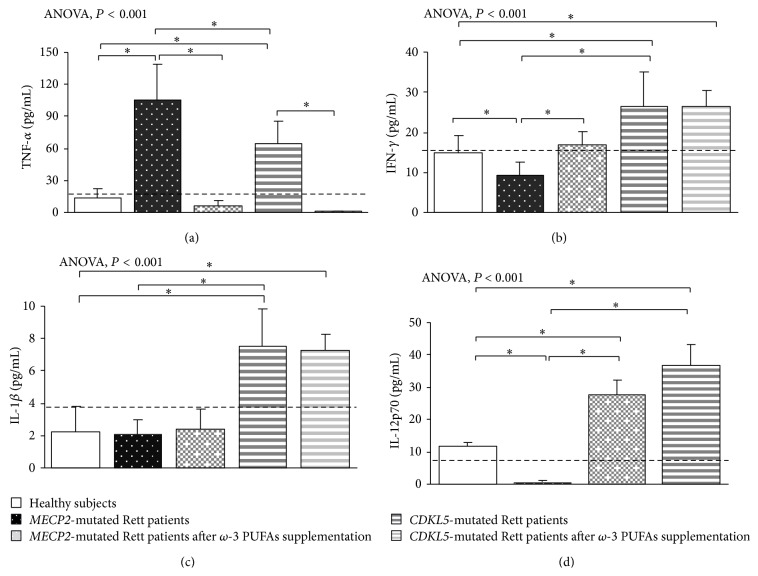

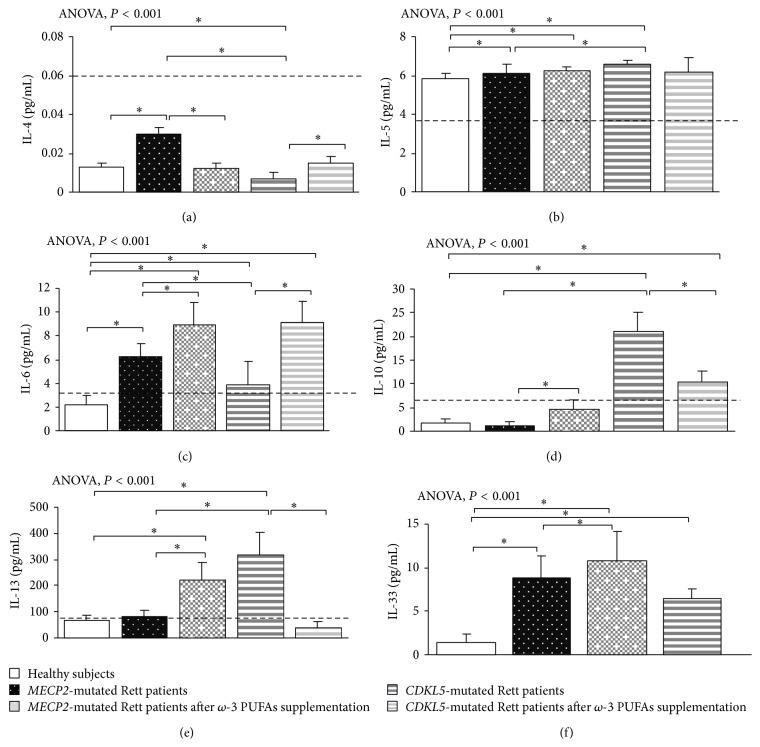

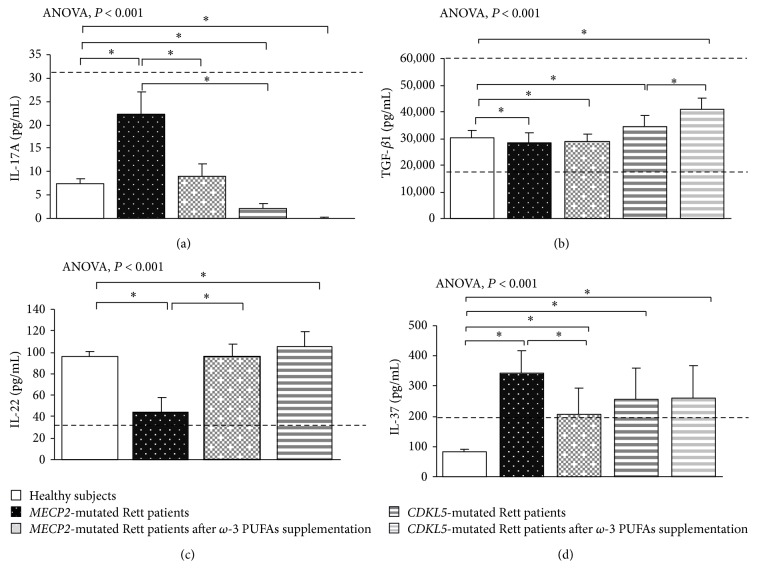

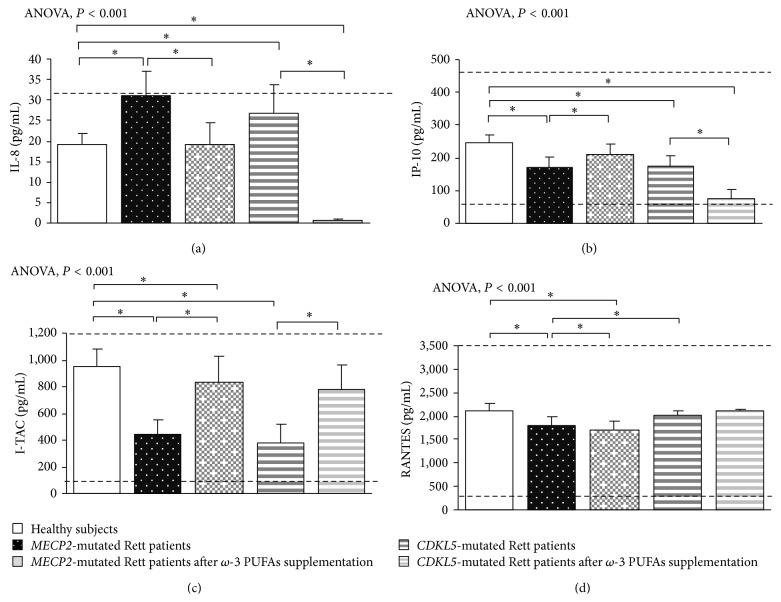

In typical MECP2-RTT, increased levels of TNF-α, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-37 plasma levels (P < 0.05) and a slight increase in IL-8 were evidenced as compared to reference range, whereas decreased levels of IFN-γ, IL-12p70, and IL-22 were observed (P < 0.05). No changes for IL-1β, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IL-17A, TGF-β1, IP-10, I-TAC, and RANTES were evidenced as compared to published range (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4) [55–58].

Figure 1.

Circulating Th1-related cytokines in MECP2- and CDKL5-mutated Rett patients before and after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise tests (P < 0.05). The dashed line denotes upper range limit as obtained from manufacturer's data sheet.

Figure 2.

Circulating Th2-related cytokines in MECP2- and CDKL5-mutated Rett patients before and after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise tests (P < 0.05). The dashed line denotes upper range limit as obtained from manufacturer's data sheet or from published literature. For IL-4, normal range is referred to literature [55]. For IL-13, normal range is referred to literature [56]. For IL-33, normal range is not indicated in the manufacturer's data sheet. However, some authors reported also a range [57].

Figure 3.

Circulating IL-17A, IL-22, TGF-β1, and IL-37 in MECP2- and CDKL5-mutated Rett patients before and after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise tests (P < 0.05). Note: levels of IL-10 are shown in Figure 2 since IL-10 is considered as both Th2 cytokine and T-reg cytokine. The dashed line denotes upper range limit as obtained from manufacturer's data sheet or from published literature. For TGF-β1, normal range is indicated by dashed lines (upper and lower range limits). For IL-37, normal range is referred to in literature [58].

Figure 4.

Circulating chemokines in MECP2- and CDKL5-mutated Rett patients before and after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise tests (P < 0.05). The dashed line denotes upper and lower range limits as obtained from manufacturer's data sheet. For IP-10, I-TAC, and RANTES, normal range is indicated by dashed lines.

Nevertheless, when compared to the examined healthy control group, typical MECP2-RTT patients also showed increased levels of IL-4, IL-8, IL-17A, and IL-33 (P < 0.05) and decreased TGF-β1, IP-10, I-TAC, and RANTES levels (P < 0.05). No changes for IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-13 were evidenced.

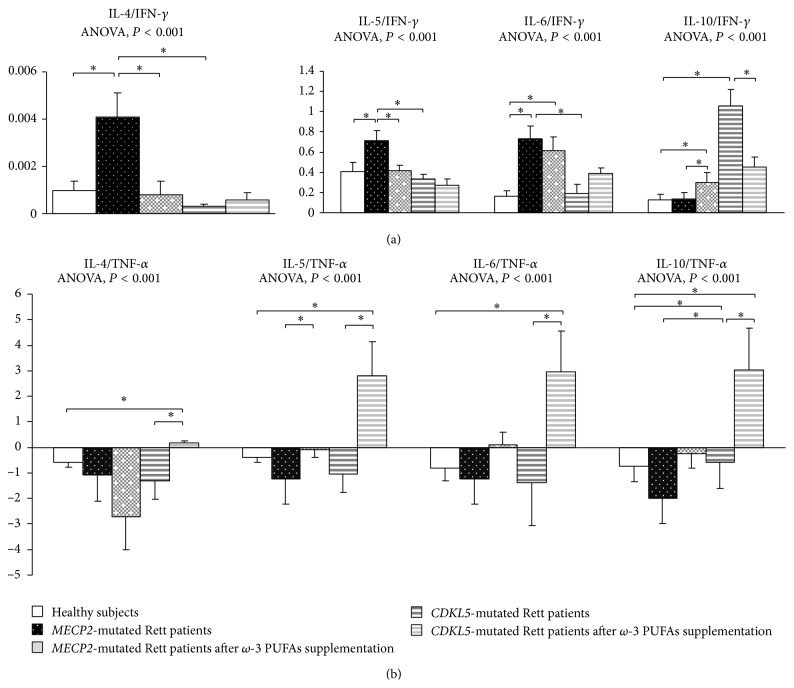

When compared to control population and based on IFN-γ, MECP2-RTT showed a Th2 shift (i.e., increased IL-4/IFN-γ, IL-5/IFN-γ, and IL-6/IFN-γ ratios) (P < 0.05) (Figure 5). Ratios based on TNF-α were difficult to interpret given the bulk increase of TNF-α level.

Figure 5.

Th2/Th1 ratio in MECP2- and CDKL5-mutated Rett patients before and after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation. (a) Comparative Th2/Th1 ratios defined on the ratio of Th2-related cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10) and INF-γ. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise tests (P < 0.05). (b) Comparative Th2/Th1 ratios defined on the ratio of Th2-related cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10) and TNF-α. Th2/Th1 ratio values are expressed in logarithmic scale and indicated as means ± standard deviations. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise tests (P < 0.05).

Overall, MECP2-RTT showed decreased levels of Th1-related cytokines (i.e., IFN-γ, IL-12p70), with the remarkable exception of increased TNF-α levels. Altogether, a Th2 shift (increased IL-5 and IL-6) was detectable.

In addition, increased levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-37 and decreased IL-22 concentration were also observed. No significant changes in T-reg-related cytokines (i.e., IL-10 and TGF- β1) and chemokines were present.

3.2.2. CDKL5-RTT

In CDKL5-RTT, increased levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-12p70, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, TGF-β1, IL-22, and IL-37 (P < 0.05) were evidenced. No changes were observed for all the other examined cytokines (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4) [55–58].

When compared to our control group, CDKL5-RTT also showed increased levels of IL-8, IL-33 (P < 0.05) with decreased IL-4, IL-17A, IP-10, and I-TAC levels (P < 0.05). No changes were evidenced for RANTES. Apart from increased IL-10/IFN-γ and IL-10/TNF-α ratios (i.e., IL-10 is a cytokine classified as both a Th2 cytokine and T-reg-related cytokine), no changes were observed for all the other examined ratios (Figure 5).

Overall, both Th1- and Th2-related (except for IL-4) cytokines were upregulated in CDKL5-RTT, together with increased levels of IL-22 and T-reg-related cytokines. No changes were observed for chemokine levels.

3.2.3. Relative Changes (Fold Variations)

In order to account for real changes, that is, independently of absolute basal concentrations, values data were submitted to double standardization (i.e., basal values of untreated MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT patients versus control values and treated MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT patients versus untreated). After standardization, some differences lost weight, whereas others gained statistical significance (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 in the Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/421624). In particular, changes in IL-10 in MECP2-RTT and IL-6, TGF-β1, IP-10, IL-5/TNF-α ratio, IL-6/TNF-α ratio, and IL-10/TNF-α ratio in CDKL5-RTT were found to be not significant after ω-3 PUFAs treatment, whereas changes in IL-5, IL-6/IFN-γ ratio, IL-4/TNF-α ratio, and IL-6/TNF-α ratio in MECP2-RTT and IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-5, IL-37, and IL-4/IFN-γ ratio, F4-NeuroPs, and GSH/GSSG ratio in CDKL5-RTT were found to be statistically significant.

3.2.4. Summary Effects of Circulating Basal Cytokine Changes in MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT

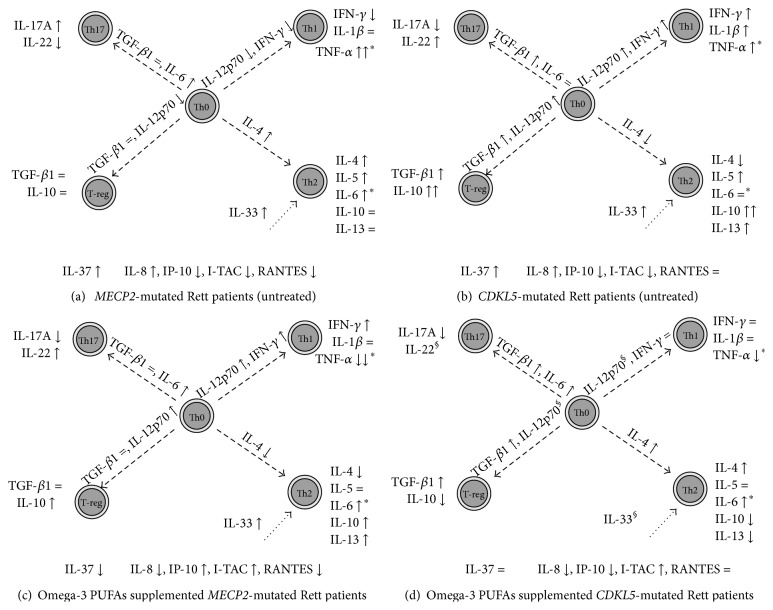

In typical MECP2-RTT, the Th2 and Th17 lineages appear to be activated. In particular, activation of Th2 lineage is more evident as compared to that of Th17 line. The Th1 lineage appears to be inhibited with the single exception of TNF-α, while no changes were observed regarding the T-reg lineage. Besides, chemokines appear to be inhibited with the single exception of IL-8. IL-33, known to be involved in Th2 differentiation, is increased. IL-37, known to counteract inflammatory status, appears to be increased and likely reflects a proinflammatory status in the untreated MECP2-RTT population (Figure 6(a)). In CDKL5-RTT, the Th1 and T-reg lineages appear to be strongly activated, whereas paradoxical effects were observed regarding Th17. An important feature of untreated CDKL5-RTT appears to be a strongly increased production of IL-10 dominating the Th2 pattern changes. Chemokines and IL-37 show the same pattern observed in MECP2-RTT (Figure 6(b)).

Figure 6.

Schematic cytokine changes in MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT. Data were based on comparisons between MECP2- and CDKL5-related Rett patients and healthy subjects reported in Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4. (a) and (b) The symbol ↓, ↑, or = indicates a significant decrease, increase, or unchanged value of the examined cytokine versus examined healthy subject values. (c) and (d) The symbol ↓, ↑, or = indicates a significant decrease, increase, or unchanged value of the examined cytokine versus untreated MECP2- and CDKL5-mutated Rett patients values. ∗Cytokines mainly secreted by macrophages; §cytokines whose assay is not available in the ω-3 PUFAs supplemented CDKL5-RTT.

Overall, several of the observed cytokine pattern changes in untreated RTT (either MECP2- or CDKL5-related RTT patients) appear to reflect a likely macrophage dysregulation/dysfunction as suggested by Cronk et al. [28]. In particular, in MECP2-RTT, a strongly increased production of TNF-α was evidenced, whereas apart from TNF-α a strongly increased release of IL-10 and IL-12p70 was observed in CDKL5-RTT.

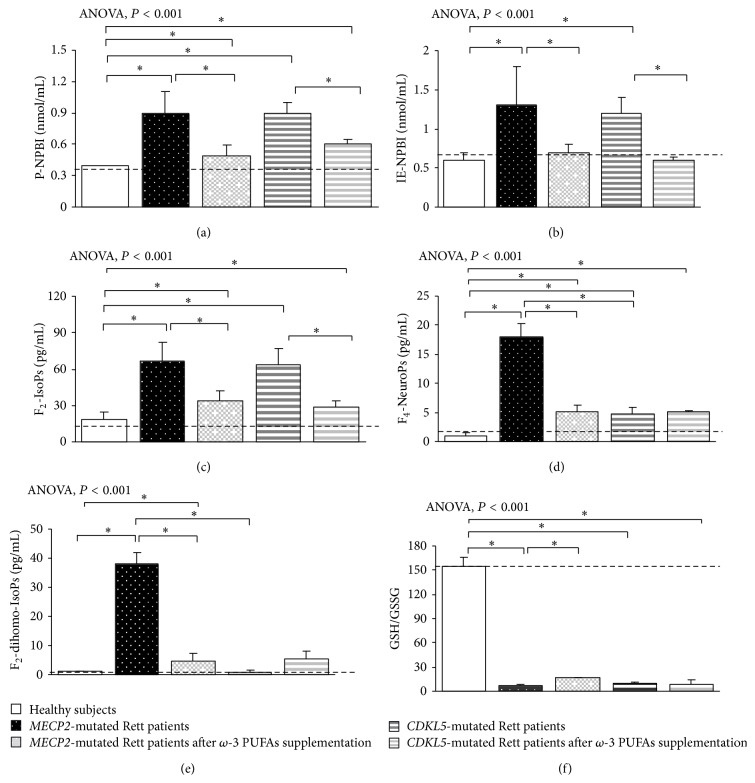

3.3. Redox Status in MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT

In typical MECP2-RTT an oxidative imbalance was evidenced, thus confirming our prior observations [12–15]. In particular, a significant increase in P-NPBI and IE-NPBI (i.e., free redox active iron), F2-IsoPs (i.e., markers of systemic OS), F4-NeuroPs (i.e., markers of brain grey matter oxidative injury), and F2-dihomo-IsoPs (i.e., markers of brain white matter oxidative injury) levels (all P < 0.05) as compared to healthy subjects is observed. In CDKL5-RTT, similar results were found (Figure 7), confirming our preliminary observations [16]. However, some differences between MECP2-RTT and CDKL5-RTT were observed. While all the examined OS markers were found to be increased in MECP2-RTT, F2-dihomo-IsoPs plasma levels in CDKL5-RTT were found to be comparable to those of the control group. The observed redox imbalance was mirrored by a strongly reduced GSH/GSSG ratio as detectable in both conditions (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Systemic redox status in MECP2- and CDKL5-mutated Rett patients before and after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise tests (P < 0.05). P-NPBI: plasma non-protein-bound iron; F2-IsoPs: plasma F2-isoprostanes; F2-dihomo-IsoPs: plasma F2-dihomo-isoprostanes; F4-NeuroPs: plasma F4-neuroprostanes; GSH: reduced glutathione; GSSG: oxidized glutathione. The dashed line denotes upper range limit from laboratory normal reference values.

3.4. Inflammatory Status in MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT

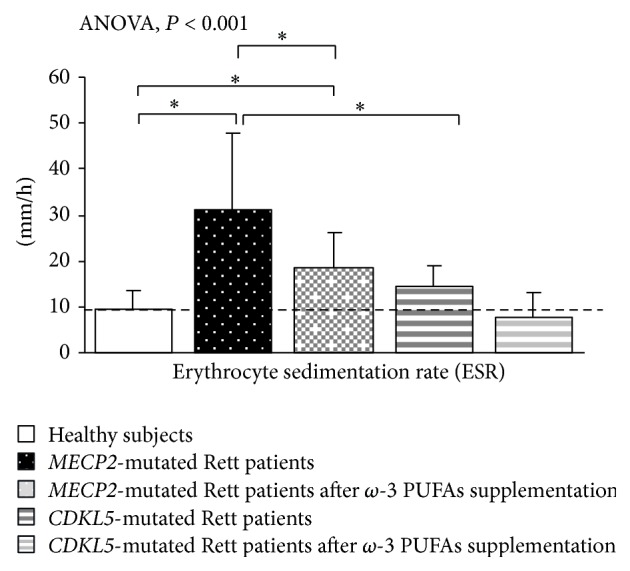

Elevated ESR values were detectable in MECP2-RTT as compared to healthy subjects (mean value 9.4 ± 5.8 mm/h), thus confirming the presence of a subclinical inflammatory status in MECP2-RTT patients [24]. A slight, albeit not statistically significant, increase in ESR was observed in CDKL5-RTT patients (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Inflammatory status in MECP2- and CDKL5-mutated Rett patients before and after ω-3 PUFAs supplementation. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise tests (P < 0.05). The dashed line denotes upper range limit as obtained from clinical laboratory.

3.5. Correlations between Cytokines, Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Status, and Phenotype Severity

In the RTT population, the cytokine-dependent response was significantly correlated with redox imbalance (i.e., P-NPBI, IE-NPBI, F2-IsoPs, F4-NeuroPs, F2-dihomo-IsoPs, and GSH/GSSG ratio), inflammatory index (i.e., ESR), or compressed clinical severity score (i.e., CCSS). Relatively to the different cytokines, in Table 1 are reported the correlation coefficients. Interestingly, we evidenced significant correlations between circulating cytokine levels, OS markers, and some individual clinical features common in RTT syndrome (i.e., seizures and scoliosis). The presence of scoliosis was significantly associated with IL-4 (r = 0.424, P < 0.0001), IFN-γ (r = −0.458, P < 0.0001), IL-12p70 (r = −0.327, P = 0.0029), IL-4/IFN-γ ratio (r = 0.491, P < 0.0001), IL-5/IFN-γ ratio (r = 0.442, P = 0.0001), and IL-6/IFN-γ ratio (r = 0.429, P = 0.0001). Epilepsy was associated with IL-5 (r = 0.347, P = 0.0020), IL-10 (r = 0.328, P = 0.0036), IL-12p70 (r = 0.370, P = 0.0001), IL-13 (r = 0.346, P = 0.0021), and F2-IsoPs (r = 0.536, P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients for the relationships between clinical severity, inflammation, redox status, and circulating cytokine.

| Clinical severity (CCSS) | ESR | P-NBPI | IE-NPBI | F2-IsoPs | F4-NeuroPs | F2-dihomo-IsoPs | GSH/GSSG ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical severity (CCSS) | — | 0.328∗∗∗ | 0.279∗∗ | 0.290∗∗ | 0.461∗∗∗ | 0.492∗∗∗ | 0.409∗∗∗ | −0.326∗∗∗ |

| ESR | — | — | 0.424∗∗∗ | 0.276∗∗ | 0.456∗∗∗ | 0.586∗∗∗ | 0.494∗∗∗ | −0.397∗∗∗ |

| TNF-α | 0.456∗∗∗ | 0.438∗∗∗ | 0.713∗∗∗ | 0.661∗∗∗ | 0.678∗∗∗ | 0.749∗∗∗ | 0.634∗∗∗ | −0.310∗∗∗ |

| IFN-γ | −0.305∗∗∗ | −0.252∗∗ | −0.091 | −0.154 | −0.088 | −0.362∗∗∗ | −0.391∗∗∗ | −0.066 |

| IL-1β | −0.231∗∗ | −0.117 | 0.218∗∗ | 0.091 | 0.145 | −0.101 | −0.176∗ | −0.158∗ |

| IL-12p70 | −0.399∗∗∗ | −0.315∗∗∗ | −0.243∗∗ | −0.302∗∗ | −0.189∗ | −0.571∗∗∗ | −0.624∗∗∗ | −0.213∗∗ |

| IL-4 | 0.419∗∗∗ | 0.520∗∗∗ | 0.483∗∗∗ | 0.456 | 0.508∗∗∗ | 0.816∗∗∗ | 0.787∗∗∗ | −0.233 |

| IL-5 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.144 | 0.022 | 0.233∗∗ | 0.052 | −0.030 | −0.372∗∗∗ |

| IL-6 | 0.002 | 0.138 | −0.042 | −0.063 | 0.052 | 0.105 | 0.012 | −0.480∗∗∗ |

| IL-10 | −0.219∗ | −0.108 | 0.218∗∗ | 0.087 | 0.214∗∗ | −0.212∗∗∗ | −0.288∗∗ | −0.250∗∗ |

| IL-13 | −0.068 | −0.071 | −0.033 | −0.066 | 0.073 | −0.173∗ | −0.247∗∗ | −0.316∗∗∗ |

| IL-33 | 0.080 | 0.190∗ | 0.197∗ | 0.113 | 0.268∗∗∗ | 0.286∗∗∗ | 0.149 | −0.582∗∗∗ |

| IL-17A | 0.446∗∗∗ | 0.555∗∗∗ | 0.431∗∗∗ | 0.392∗∗∗ | 0.382∗∗ | 0.667∗∗∗ | 0.675∗∗∗ | −0.222∗∗ |

| IL-22 | −0.379∗∗∗ | −0.427∗∗∗ | −0.549∗∗ | −0.548∗∗∗ | −0.558∗∗∗ | −0.817∗∗∗ | −0.821∗∗∗ | 0.283∗∗ |

| TGF-β1 | −0.246∗∗ | −0.309∗∗∗ | 0.099 | −0.043 | −0.074 | −0.218∗∗ | −0.235∗∗ | 0.010 |

| IL-37 | 0.197∗ | 0.431∗∗∗ | 0.525∗∗ | 0.409∗∗ | 0.625∗∗∗ | 0.625∗∗∗ | 0.499∗∗ | −0.556∗∗∗ |

| IL-8 | 0.173 | 0.180∗ | 0.321∗∗ | 0.322∗∗ | 0.392∗∗∗ | 0.361∗∗∗ | 0.358∗∗ | −0.151 |

| IP-10 | −0.110 | −0.191∗ | −0.397∗∗ | −0.259∗∗ | −0.365∗∗ | −0.377∗∗ | −0.392∗∗ | 0.443∗∗∗ |

| I-TAC | −0.189∗∗ | −0.407∗∗∗ | −0.664∗∗∗ | −0.567∗∗∗ | −0.697∗∗∗ | −0.582∗∗∗ | −0.502∗∗∗ | −0.447∗∗∗ |

| RANTES | 0.012 | −0.284∗∗∗ | −0.134 | −0.102 | −0.249 | −0.278∗∗ | 0.176∗ | 0.541∗∗∗ |

| IL-4/IFN-γ | 0.302∗∗ | 0.336∗∗∗ | 0.456∗∗∗ | 0.393∗∗∗ | 0.516∗∗∗ | 0.817∗∗∗ | 0.687∗∗∗ | −0.209∗∗ |

| IL-5/IFN-γ | 0.242∗∗ | 0.499∗∗∗ | 0.266∗∗ | 0.221∗∗ | 0.272∗∗ | 0.449∗∗∗ | 0.443∗∗∗ | −0.133 |

| IL-6/IFN-γ | 0.174 | 0.321∗∗∗ | 0.164∗ | 0.128 | 0.220∗∗ | 0.367∗∗∗ | 0.290∗∗ | −0.411∗∗∗ |

| IL-10/IFN-γ | −0.141 | −0.032 | 0.189∗ | 0.098 | 0.174∗ | −0.132 | −0.197∗ | −0.229∗∗ |

| IL-4/TNF-α | −0.235∗∗ | −0.166∗ | −0.115 | −0.179∗∗ | 0.470∗∗∗ | 0.704∗∗∗ | −0.117 | 0.008 |

| IL-5/TNF-α | −0.302∗∗∗ | −0.162∗ | −0.134 | −0.203∗∗ | −0.149 | −0.214∗∗∗ | −0.175∗ | −0.005 |

| IL-6/TNF-α | −0.124 | −0.098 | −0.113 | −0.165∗ | −0.103 | −0.149 | −0.127 | −0.111 |

| IL-10/TNF-α | −0.228∗∗ | −0.065 | 0.023 | −0.055 | 0.059 | −0.109 | −0.137 | −0.127 |

Data are expressed as correlation coefficients. Bold characters indicate statistically significant associations. Asterisks denote P values: ∗ P < 0.05; ∗∗0.05 < P < 0.001; ∗∗∗ P < 0.0001. CCSS: compressed clinical severity score [46]; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; P-NPBI: plasma non-protein-bound iron; F2-IsoPs: plasma F2-isoprostanes; F2-dihomo-IsoPs: plasma F2-dihomo-isoprostanes; F4-NeuroPs: plasma F4-neuroprostanes; IE-NBPI: intraerythrocyte non-protein-bound iron; GSH: reduced glutathione; GSSG: oxidized glutathione.

A stepwise multiple regression analysis showed that clinical severity (i.e., CCSS) was significantly associated with cytokine dysregulation and aberrant redox homeostasis (P < 0.001) (Table 2). In fact, circulating cytokine levels accounted for 40.7% to 81.2% of the whole variance observed for inflammation and redox imbalance. In particular, CCSS was found to be related to TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-4, and IL-12p70 levels and associated with F2-IsoPs, F4-NeuroPs, and GSH/GSSG ratio. On the other hand, OS markers were mainly related to TNF-α, IL-37, and I-TAC levels. This data suggests the existence of a complex interplay between cytokine modulation, redox imbalance, inflammatory status, and clinical severity in RTT.

Table 2.

Relationship between clinical severity, redox status, subclinical inflammation, and circulating cytokines for the whole population: results of a stepwise multiple regression analysis.

| Dependent variable | Final stepwise model | R 2 | R 2 adjusted | Multiple correlation coefficient | Residual SD | F-ratio | Significance of P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected predictor variables | R partial | P value | |||||||

|

Clinical severity (CCSS) [46] |

(+) TNF-α | 0.406 | <0.0001 | 0.490 | 0.476 | 0.699 | 2.66 | 35.72 | <0.001 |

| (+) IL-17A | 0.235 | 0.0037 | |||||||

| (+) IL-4 | 0.362 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| (−) IL-12p70 | 0.581 | <0.0001 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

|

Clinical severity (CCSS) [46] |

(−) GSH/GSSG | 0.779 | <0.0001 | 0.809 | 0.805 | 0.899 | 1.59 | 220.39 | <0.001 |

| (+) F4-NeuroPs | 0.235 | 0.0029 | |||||||

| (+) F2-IsoPs | 0.184 | 0.0205 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| ESR | (+) IL-17A | 0.319 | <0.0001 | 0.304 | 0.292 | 0.552 | 10.84 | 25.38 | <0.001 |

| (+) IL-4/IFN-γ | 0.475 | 0.0009 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| P-NPBI | (+) TNF-α | 0.532 | <0.0001 | 0.563 | 0.556 | 0.750 | 0.18 | 74.79 | <0.001 |

| (−) I-TAC | 0.358 | 0.0001 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| F2-IsoPs | (+) TNF-α | 0.383 | <0.0001 | 0.581 | 0.570 | 0.762 | 12.93 | 53.23 | <0.001 |

| (+) IL-37 | 0.285 | 0.0018 | |||||||

| (−) I-TAC | 0.434 | <0.0001 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| F2-dihomo-IsoPs | (−) IL-22 | 0.596 | <0.0001 | 0.711 | 0.704 | 0.843 | 9.95 | 94.52 | <0.001 |

| (+) IL-4/IFN-γ | 0.260 | 0.0047 | |||||||

| (+) IL-17A | 0.194 | 0.0359 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| F4-NeuroPs | (−) IL-22 | 0.553 | <0.0001 | 0.874 | 0.870 | 0.935 | 2.26 | 197.65 | <0.001 |

| (+) IL-4/IFN-γ | 0.247 | 0.0074 | |||||||

| (+) IL-37 | 0.201 | 0.0235 | |||||||

| (−) IL-12p70 | 0.606 | <0.0001 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| IE-NPBI | (+) TNF-α | 0.493 | <0.0001 | 0.440 | 0.431 | 0.664 | 0.32 | 48.02 | <0.001 |

| (−) I-TAC | 0.221 | 0.0136 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| GSH/GSSG ratio | (+) IL-22 | 0.678 | <0.0001 | 0.804 | 0.797 | 0.897 | 1.89 | 117.05 | <0.001 |

| (−) IL-37 | 0.247 | 0.0076 | |||||||

| (−) RANTES | 0.476 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| (+) I-TAC | 0.684 | <0.0001 | |||||||

Plus and minus signs in brackets indicate positive or negative associations. CCSS: compressed clinical severity score [46]; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; P-NPBI: plasma non-protein-bound iron; F2-IsoPs: plasma F2-isoprostanes; F2-dihomo-IsoPs: plasma F2-dihomo-isoprostanes; F4-NeuroPs: plasma F4-neuroprostanes; IE-NBPI: intraerythrocyte non-protein-bound iron; GSH: reduced glutathione; GSSG: oxidized glutathione.

3.6. Omega-3 PUFAs Effects

During the study, compliance to the administered ω-3 PUFAs was optimal, with no side effects requiring the drop-out from the protocol treatment.

After ω-3 PUFAs supplementation, a significant reduction of clinical severity was observed in MECP2-RTT patients, as compared to the basal status before treatment population (CCSS −22.4%; P < 0.05). These data confirm our previous results in typical RTT [13, 14, 59]. A significant decrease in clinical severity (CCSS −37%; P < 0.05) was also observed in ω-3 PUFAs supplemented CDKL5-RTT population.

In supplemented MECP2-RTT patients, a significant decrease in TNF-α, IL-4, IL-17A, IL-37, IL-8, and RANTES plasma levels (P < 0.05) was evidenced, whereas significantly increased levels were observed for IFN-γ, IL-12p70, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, IL-33, IL-22, IP-10, and I-TAC plasma levels (P < 0.05) as compared to unsupplemented MECP2-RTT patients. No significant changes were observed for IL-1β, IL-5, and TGF-β1 (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4) [55–58].

When compared to unsupplemented MECP2-RTT patients, IL-4/IFN-γ and IL-6/IFN-γ ratios were decreased whereas the IL-10/IFN-γ ratio was increased (P < 0.05). As it concerns TNF-α based ratios, IL-5/TNF-α and IL-6/TNF-α were increased, whereas IL-4/TNF-α was reduced (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

In supplemented CDKL5-RTT patients, a significant decrease in TNF-α, IL-10, IL-13, IL-8, and IP-10 plasma levels (P < 0.05) was evidenced, as compared to unsupplemented CDKL5-RTT patients, whereas significantly increased levels were evidenced for IL-4, IL-6, TGF-β1, and I-TAC (P < 0.05). No significant changes were observed for IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-5, IL-17A, IL-37, and RANTES (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4) [55–58]. The evaluation of circulating IL-12p70, IL-33, and IL-22 was not applicable due to insufficient sample volumes.

When compared to unsupplemented CDKL5-RTT patients, only IL-10/IFN-γ ratio was decreased whereas all ratios based on TNF-α were increased (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Interestingly, ω-3 PUFAs induced a similar hypersecretion in IL-6 associated with a similar depression in TNF-α and IL-8 circulating levels for both MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT.

In supplemented MECP2-RTT, all examined OS markers were significantly decreased (P < 0.05) and GSH/GSSG ratio increased (P < 0.05). Only IE-NPBI levels resulted as normalized, as compared to those of the control subjects (Figure 7).

In supplemented CDKL5-RTT, P-NPBI, IE-NPBI, and F2-IsoPs levels were significantly decreased as compared to those of unsupplemented CDKL5-RTT (P < 0.05). No differences were observed for F4-NeuroPs, F2-dihomo-IsoPs, and GSH/GSSG ratio (Figure 7).

Following 12 months of ω-3 PUFAs supplementation, ESR values were significantly reduced in MeCP2-RTT as compared to untreated MECP2-population (−43.5%) but remained elevated as compared to healthy subjects. In supplemented CDKL5-RTT patients, ESR values were decreased (−46.2%) and the values were similar to those of the control group (Figure 8).

Overall, ω-3 PUFAs appear to modulate Th1-related cytokines in a similar way in both MECP2-RTT and CDKL5-RTT. This counterbalance was mirrored by decreased OS markers levels and ESR values.

3.6.1. Summary Effects of ω-3 PUFAs Supplementation on Circulating Cytokine Changes in MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT

In MECP2-RTT, a prolonged high-dosage strongly suppressed TNF-α production and regulated the Th1 cytokine pattern and T-reg lineage as well as Th2 with the exception of IL-4. As it concerns chemokines, ω-3 PUFAs effect seems to be regulatory with a single exception of a persistently inhibited RANTES secretion. IL-37 appears to be inhibited as the likely net result of anti-inflammatory action (Figure 6(c)).

As compared to the MECP2-RTT picture, the effects of ω-3 PUFAs in CDKL5-RTT appear to be more difficult to be interpreted in a univocal way. For Th1 lineage, ω-3 PUFAs modulate the examined cytokines in a similar way to that observed in MECP2-RTT. Paradoxical responses within the Th2 and T-reg lineages were observed. As far as chemokines are concerned, ω-3 PUFAs partially counteract baseline changes, with the exceptions of IP-10 and RANTES. On the other hand, IL-37 levels appear to be unchanged (i.e., elevated levels) (Figure 6(d)).

4. Discussion

Our findings indicate, for the first time, a complex cytokine dysregulation in RTT. In particular, in MECP2-RTT, a Th2-shifted balance was evidenced, whereas in CDKL5-RTT both Th1- and Th2-related (except for IL-4) cytokines were found to be upregulated.

Almost specular changes were observed regarding IL-22 and T-reg cytokine TGF-β1 between these disorders, decreased IL-22 and unchanged T-reg levels in MECP2-RTT versus increased IL-22 and T-reg levels in CDKL5-RTT.

The observed cytokine dysregulation was proportional to clinical severity, inflammatory status, and redox imbalance. Interestingly, the macrophage has been very recently reported as a key target cell for MeCP2 action in a mouse model of Mecp2 loss-of-function [28]. Interestingly, several of the assayed cytokines, whose circulating levels were found to be abnormal in MECP2-RTT girls, included macrophage-related cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-10, TGF-β1, IL-8, and RANTES [60].

Although the characteristic cytokine pattern in RTT appears to be inhomogeneous, it includes high plasma levels of TNF-α and IL-5. TNF-α is a proinflammatory cytokine and produced in response to inflammatory stimuli. Elevated levels of TNF-α have been reported in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, irritable bowel disease, and psoriasis [61]. IL-5, a Th2 cytokine, acts on eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, and B cells and elevated levels were found in allergy asthma and hypereosinophilic syndrome [62].

Actually, none of the clinical features observed in these associated pathologies are usually present in RTT, either MECP2- or CDKL5-related disorder.

Our data confirm the presence of a significant proinflammatory status in MECP2-RTT. For the first time, we observed an upregulation of both Th1- and Th2-related cytokines in CDKL5-RTT, which does not translate into increased inflammatory marker levels, likely due to a bulk increase in the anti-inflammatory IL-10 (about 21-fold), a key regulator cytokine of immune response [50].

The clinical translation for the observed changes remains to be elucidated. Nevertheless, cytokine dysregulation in MECP2-RTT appears to be associated with a proinflammatory status, as evidenced by raised ESR values and an acute phase protein response [24]. On the other hand, the final result in CDKL5-RTT remains unclear, given that ESR was found to be slightly higher than control values, although not statistically different. We have previously described in MECP2-RTT patients the presence of respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease- (RB-ILD-) like features at the high-resolution CT (HRCT) images of the lungs in up to half of patients aged 10 years or more [63]. More recently, histologic evidence for an inflammatory lung disease has been reported by our group in a murine model of the disease [25]. Therefore, it is conceivable that the unexplained persistent inflammatory process in MECP2-RTT could be the possible result of an ineffective chemotaxis, at least in some anatomical districts. No information to this regard is available to date for CDKL5-RTT.

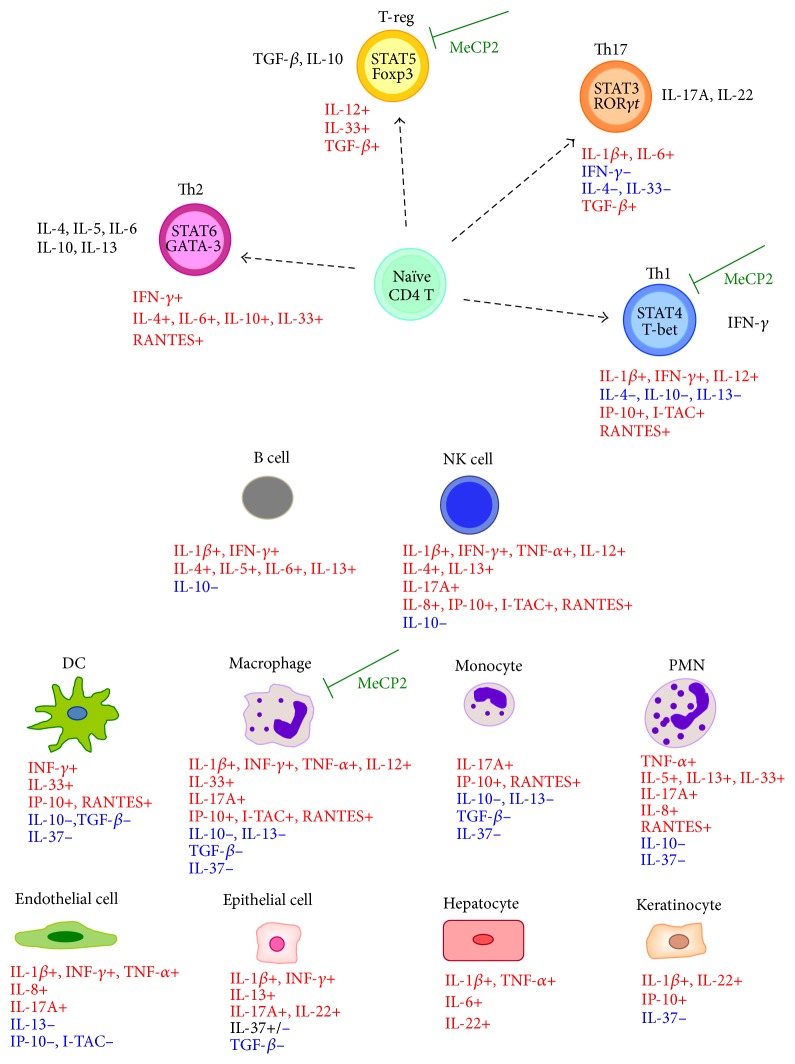

Prior reports have suggested the occurrence of defective Th1 differentiation in RTT [30, 34]. Our findings in MECP2-RTT appear to be in line with this suggestion, given that levels of cytokines known to be produced or related to Th1 are generally reduced, with the only notable exception of TNF-α (Figure 9) [61, 64]. On the contrary, Th1 cytokines were found to be all increased in CDKL5-RTT. To date, no information concerning immunological response, inflammatory status, or defense against infections is available for this condition.

Figure 9.

Schematic overview of the known effects of cytokines on immune and nonimmune cells. Blue font indicates anti-inflammatory effects. Red font indicates proinflammatory/activation effects. Relationships were reconstructed on the basis of literature [61, 62, 64, 66]. The modulatory effects of MeCP2 are referred to in [27, 28, 30]. Th1: T helper 1 cell; Th2: T helper 2 cell; Th17: T helper 17 cell; T-reg: T-regulatory cell, NK cell: natural killer cell; DC: dendritic cell; PMN: polymorphonuclear leukocyte.

On the other hand, Th2-cytokines were found to be generally increased in RTT. In particular, a significant increase in IL-5, IL-6 was observed in MECP2-RTT whereas in CDKL5-RTT IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 levels were increased. Thus the Th2-dependent response appears to be upregulated in RTT independently of the mutated gene. This observation is also in line with the hypothesis of a compensatory effect of immune response related to a defective Th1 differentiation [30, 34]. Possible clinical consequences of this Th2/Th1 shift imbalance in RTT could be a risk factor for autoimmunity, which is consistent with earlier reports on a link between MeCP2 and autoimmunity [41–43].

Although Fiumara et al. [31] did not find anti-neuronal and anti-myelin ganglioside as well as anti-nuclear, anti-striated muscle, and anti-smooth muscle autoantibodies, a recent report by Papini et al. [44] evidenced high levels of serum anti-N(Glc) autoantibodies in RTT.

The immune regulatory response appears to be also aberrant in RTT in that while the cytokines produced by T-reg cells (i.e., IL-10, TGF-β1) [50] were unchanged in MECP2-RTT, they appear to be increased in CDKL5-RTT. T-reg cells are critical in regulating the inflammatory process and Mecp2 has been recently shown to be a crucial player in determining T-reg resilience against inflammation [27]. The loss of control of the T-reg function is one of the known causes for the loss of the immune tolerance [65].

Interestingly, the behaviour of circulating IL-22 was the opposite in MECP2-RTT and in CDKL5-RTT. Although IL-22, a proinflammatory cytokine, is considered to be upregulated in chronic inflammatory diseases, its role seems to be depending on the biological context in that it can be able to favour the antimicrobial defense, regeneration, and protection against damage and induce acute phase reactants, as well as some chemokines [66]. Another proinflammatory cytokine, IL-17A, when compared to our control group, was found to be significantly increased in MECP2-RTT but significantly decreased in CDKL5-RTT. Likewise, when compared to our control group, levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-37 [49] were found to be significantly elevated in MECP2-RTT as the consequence of a compensatory mechanism.

Overall, the observed cytokine dysregulation does not appear to translate into a primary immunodeficiency, nor in a classical autoimmune disease [44].

Although the reasons behind to date observed cytokine dysregulation in RTT are unknown, possible explanations may include either a defective genetic/epigenetic control on target genes or an aberrant redox imbalance. Our findings, combined with published evidence, suggest that Mecp2 loss-of-function mutations could lead to abnormal redox homeostasis via the Jak/STAT3 signaling pathway [67, 68]. Our demonstration of a redox imbalance in MECP2-RTT and CDKL5-RTT confirms and extends prior evidence of OS as a hallmark feature of RTT [16, 18]. Oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, with consequent enhanced formation of IsoPs and NeuroPs [69, 70], is one of major features of OS. A key difference between MECP2-RTT and CDKL5-RTT appears to reside in the F2-dihomo-IsoPs behaviour, in that their levels are comparable to those of control group in CDKL5-RTT, whereas they are significantly increased in MECP2-RTT. To date, no clear explanation exists for these findings; it might reflect the clinical difference between two disorders. Clinical differences between the disorders may account for the observed redox pattern differences, in that MECP2-RTT can be considered a multisystemic disease, whereas CDKL5-RTT is essentially a myoclonic encephalopathy.

Therefore, a complex interplay exists between cytokines, redox homeostasis, and inflammatory status in RTT. Statistically, cytokine levels were found to explain a very consistent fraction of the observed variance for subclinical inflammation and redox abnormality, thus indicating that the aberrant immune response, as regulated by cytokine signalling, is intimately related to redox imbalance and both are likely responsible for modulating phenotype severity in RTT.

Likely, the more striking result of our study is the evidence of a persistent and unexplained hyper-TNF-α status in RTT. Hyperleptinemia in MECP2-RTT has been previously reported by Blardi et al. [71]. The findings of our study would allow a novel data interpretation from a different perspective. Leptin is able to modulate both innate and adaptive immune response [1]. Indeed, the overall leptin action in the immune system is that of a proinflammatory effect, activating proinflammatory cells, promoting Th1 responses, and mediating the production of the other proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-2, or IL-6 [72]. Therefore, it is plausible that, in untreated MECP2-RTT girls, the hyper-TNF-α status might be triggered by hyperleptinemia.

A beneficial effect of ω-3 PUFAs in MECP2-RTT has been previously reported by our group on redox homeostasis [13, 14, 59, 73, 74], subclinical inflammation [75], fatty acid composition of erythrocyte membranes [76], and clinical severity [13, 14, 59, 73].

EPA and DHA, that is, the major ω-3 PUFAs contained in fish oil, are known to partly inhibit several aspects of inflammation, including leukocyte chemotaxis, adhesion molecule expression, production of eicosanoids, production of inflammatory cytokines, and T-helper 1 lymphocyte reactivity [77]. The critical interplay between inflammation and OS in the underlying mechanisms leading from gene mutation to disease expression [78] is further supported by the modulatory effect of ω-3 PUFAs on cytokine patterns in RTT. Our findings demonstrate that ω-3 PUFAs partially counterbalance cytokine changes, aberrant redox homeostasis, and proinflammatory status.

In particular, a consistent number of the investigated cytokines appear to be rescued following a 12-month high dosage supplementation. Target cytokines for ω-3 PUFAs in MECP2-RTT include TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17A, TGF-β1, IL-22, IL-37, IL-8, IP-10, and I-TAC, whereas they include TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-8, IP-10, and I-TAC in CDKL5-RTT. These data appear to further support and extend prior reports on the immunomodulatory effects of DHA and EPA in biological systems.

The present study indicates that RTT is associated with a subclinical immune dysregulation, as a likely consequence of a defective inflammation regulatory signaling system. This abnormal regulation of the inflammatory response appears to be an unrecognized hallmark feature of RTT, intimately related to OS imbalance and likely contributing to disease expression.

Supplementary Material

Relative changes (as fold variations) for inflammatory status, circulating cytokines, and redox status in MECP2- and CDKL5- mutated Rett patients. In order to account for real changes of the examined variables, i.e., independently of absolute basal concentrations, we performed data analysis through a double standardization (i.e., basal values of untreated MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT patients vs. control values and treated MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT patients vs. untreated) (Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2). After standardization, some differences loosed weight in both ω -3 PUFAs supplemented MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT. In particular, changes in IL-10 in MECP2-RTT and changes in IL-6, TGF-b1, IL-37, IP-10, IL-5/ TNF-α ratio, IL-6/ TNF-α ratio, IL-10/ TNF-α ratio in CDKL5-RTT were found to be not significant. Likewise, other differences gained statistical significance as changes in IL-5, IL-6/IFN-g ratio, IL-4/ TNF-α ratio, IL-6/ TNF-α ratio in MeCP2-RTT and IFN-g, IL-1b, IL-5, IL-37, IL-4/ IFN-g ratio, F4-NeuroPs, and GSH/GSSG ratio in CDKL5-RTT.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Pierluigi Tosi, Dr. Silvia Briani, and Dr. Roberta Croci from the Administrative Direction of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese for continued support to their studies and prior purchasing of the gas spectrometry instrumentation, Norwegian Fish Oil (Trondheim, Norway), and Dr. Ezio Toni (Transforma AS Italia, Forlì, Italy) for helpful technical information on the fish oil products and access to official quality control certificates. They also thank Roberto Faleri from the Medical Central Library for online bibliographic research assistance; they acknowledge the Medical Genetics Unit of the Siena University (Head: Professor Alessandra Renieri) for MECP2 and CDKL5 gene mutation analysis. They heartily thank professional singer Matteo Setti (http://www.matteosetti.com/) for many charity concerts and continued interest in the scientific aspects of their research. This work was supported by the Regione Toscana (Bando Salute 2009; “Antioxidants (ω-3 polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, lipoic acid) supplementation in Rett syndrome: A novel approach to therapy,” RT no. 142).

Disclosure

Silvia Leoncini, Claudio De Felice, and Cinzia Signorini are co-first authors.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Silvia Leoncini, Claudio De Felice, and Cinzia Signorini were responsible for concept. Silvia Leoncini, Claudio De Felice, Cinzia Signorini, Marcello Rossi, Roberto Guerranti, Lucia Ciccoli, and Joussef Hayek carried out the experimental design. Cytokines determination was done by Silvia Leoncini, Cinzia Signorini, and Gloria Zollo. Clinical assessment was done by Joussef Hayek and Claudio De Felice. Blood sampling was carried out by Joussef Hayek. Routine chemistry was done by Roberto Guerranti and Alessio Cortelazzo. Sample preparation was carried out by Silvia Leoncini. NPBI assays were done by Silvia Leoncini. Isoprostanes and neuroprostanes assays were done by Cinzia Signorini, Thierry Durand, and Jean-Marie Galano. Glutathione assays were done by Silvia Leoncini and Gloria Zollo. Data analysis was carried out by Claudio De Felice, Silvia Leoncini, Cinzia Signorini, and Gloria Zollo. Data interpretation, paper drafting, and paper approval were done by all authors.

References

- 1.Amir R. E., Van den Veyver I. B., Wan M., Tran C. Q., Francke U., Zoghbi H. Y. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl- CpG-binding protein 2. Nature Genetics. 1999;23(2):185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chahrour M., Zoghbi H. Y. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56(3):422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mari F., Azimonti S., Bertani I., et al. CDKL5 belongs to the same molecular pathway of MeCP2 and it is responsible for the early-onset seizure variant of Rett syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(14):1935–1946. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagberg B. Clinical manifestations and stages of Rett syndrome. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2002;8(2):61–65. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laurvick C. L., de Klerk N., Bower C., et al. Rett syndrome in Australia: a review of the epidemiology. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;148(3):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christodoulou J., Ho G. MECP2-related disorders. In: Pagon R. A., Adam M. P., Ardinger H. H., et al., editors. GeneReviews. Seattle, Wash, USA: University of Washington; 1993–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guy J., Cheval H., Selfridge J., Bird A. The role of MeCP2 in the brain. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2011;27:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song C., Feodorova Y., Guy J., et al. DNA methylation reader MECP2: cell type- and differentiation stage-specific protein distribution. Epigenetics & Chromatin. 2014;7(1):p. 17. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carouge D., Host L., Aunis D., Zwiller J., Anglard P. CDKL5 is a brain MeCP2 target gene regulated by DNA methylation. Neurobiology of Disease. 2010;38(3):414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahi-Buisson N., Nectoux J., Rosas-Vargas H., et al. Key clinical features to identify girls with CDKL5 mutations. Brain. 2008;131(10):2647–2661. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehr S., Wilson M., Downs J., et al. The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2013;21(3):266–273. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Felice C., Ciccoli L., Leoncini S., et al. Systemic oxidative stress in classic Rett syndrome. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2009;47(4):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leoncini S., De Felice C., Signorini C., et al. Oxidative stress in Rett syndrome: natural history, genotype, and variants. Redox Report. 2011;16(4):145–153. doi: 10.1179/1351000211y.0000000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Signorini C., De Felice C., Leoncini S., et al. F4-neuroprostanes mediate neurological severity in Rett syndrome. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2011;412(15-16):1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Felice C., Signorini C., Durand T., et al. F2-dihomo-isoprostanes as potential early biomarkers of lipid oxidative damage in Rett syndrome. Journal of Lipid Research. 2011;52(12):2287–2297. doi: 10.1194/jlr.p017798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Felice C., Signorini C., Leoncini S., et al. The role of oxidative stress in Rett syndrome: an overview. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1259(1):121–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Signorini C., Leoncini S., De Felice C., et al. Redox imbalance and morphological changes in skin fibroblasts in typical Rett syndrome. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2014;2014:10. doi: 10.1155/2014/195935.195935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Felice C., Della Ragione F., Signorini C., et al. Oxidative brain damage in Mecp2-mutant murine models of Rett syndrome. Neurobiology of Disease. 2014;68:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardaioli E., Dotti M. T., Hayek G., Zappella M., Federico A. Studies on mitochondrial pathogenesis of Rett syndrome: ultrastructural data from skin and muscle biopsies and mutational analysis at mtDNA nucleotides 10463 and 2835. Journal of Submicroscopic Cytology and Pathology. 1999;31(2):301–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kriaucionis S., Paterson A., Curtis J., Guy J., MacLeod N., Bird A. Gene expression analysis exposes mitochondrial abnormalities in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26(13):5033–5042. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01665-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pecorelli A., Leoni G., Cervellati F., et al. Genes related to mitochondrial functions, protein degradation, and chromatin folding are differentially expressed in lymphomonocytes of rett syndrome patients. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:18. doi: 10.1155/2013/137629.137629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold W. A., Williamson S. L., Kaur S., et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the skeletal muscle of a mouse model of Rett syndrome (RTT): implications for the disease phenotype. Mitochondrion. 2014;15(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller M., Can K. Aberrant redox homoeostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction in Rett syndrome. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2014;42(4):959–964. doi: 10.1042/BST20140071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortelazzo A., De Felice C., Guerranti R., et al. Subclinical inflammatory status in Rett syndrome. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014;2014:3. doi: 10.1155/2014/480980.480980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Felice C., Rossi M., Leoncini S., et al. Inflammatory lung disease in Rett syndrome. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014;2014:15. doi: 10.1155/2014/560120.560120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lal G., Zhang N., Van Der Touw W., et al. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(1):259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li C., Jiang S., Liu S. Q., et al. MeCP2 enforces Foxp3 expression to promote regulatory T cells' resilience to inflammation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(27):E2807–E2816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401505111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cronk J. C., Derecki N. C., Ji E., et al. Methyl-CpG binding protein 2 regulates microglia and macrophage gene expression in response to inflammatory stimuli. Immunity. 2015;42(4):679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramocki M. B., Tavyev Y. J., Peters S. U. The MECP2 duplication syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2010;152(5):1079–1088. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang S., Li C., McRae G., et al. MeCP2 reinforces STAT3 signaling and the generation of effector CD4+ T cells by promoting miR-124-mediated suppression of SOCS5. Science Signaling. 2014;7(316, article ra25) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiumara A., Sciotto A., Barone R., et al. Peripheral lymphocyte subsets and other immune aspects in Rett syndrome. Pediatric Neurology. 1999;21(3):619–621. doi: 10.1016/S0887-8994(99)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Messahel S., Pheasant A. E., Pall H., Kerr A. M. Abnormalities in urinary pterin levels in Rett syndrome. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2000;4(5):211–217. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2000.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reichelt K. L., Skjeldal O. IgA antibodies in Rett syndrome. Autism. 2006;10(2):189–197. doi: 10.1177/1362361306062024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derecki N. C., Privman E., Kipnis J. Rett syndrome and other autism spectrum disorders-brain diseases of immune malfunction. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15(4):355–363. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derecki N. C., Cronk J. C., Lu Z., et al. Wild-type microglia arrest pathology in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Nature. 2012;484(7392):105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plioplys A. V., Greaves A., Kazemi K., Silverman E. Lymphocyte function in autism and Rett syndrome. Neuropsychobiology. 1994;29(1):12–16. doi: 10.1159/000119056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jellinger K., Seitelberger F. Neuropathology of Rett syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1986;24(1):259–288. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong D. D. Neuropathology of Rett syndrome. Journal of Child Neurology. 2005;20(9):747–753. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200082401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ariani F. Analisi dei geni HLA per valutare la suscettibilità genetica ai vaccini come cofattore nella patogenesi della sindrome di Rett. Proceedings of the AIR Congress; 2012; Naples, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grillo E., Lo Rizzo C., Bianciardi L., et al. Revealing the complexity of a monogenic disease: Rett syndrome exome sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056599.e56599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawalha A. H., Webb R., Han S., et al. Common variants within MECP2 confer risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001727.e1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webb R., Wren J. D., Jeffries M., et al. Variants within MECP2, a key transcription regulator, are associated with increased susceptibility to lupus and differential gene expression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009;60(4):1076–1084. doi: 10.1002/art.24360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cobb B. L., Fei Y., Jonsson R., et al. Genetic association between methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2) and primary Sjögren's syndrome. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2010;69(9):1731–1732. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.122903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papini A. M., Nuti F., Real-Fernandez F., et al. Immune dysfunction in rett syndrome patients revealed by high levels of serum anti-N(Glc) IgM antibody fraction. Journal of Immunology Research. 2014;2014:6. doi: 10.1155/2014/260973.260973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neul J. L., Kaufmann W. E., Glaze D. G., et al. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Annals of Neurology. 2010;68(6):944–950. doi: 10.1002/ana.22124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neul J. L., Fang P., Barrish J., et al. Specific mutations in methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 confer different severity in Rett syndrome. Neurology. 2008;70(16):1313–1321. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000291011.54508.aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piva E., Pajola R., Temporin V., Plebani M. A new turbidimetric standard to improve the quality assurance of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate measurement. Clinical Biochemistry. 2007;40(7):491–495. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leroux-Roels G., Offner F., Philippe J., Vermeulen A. Influence of blood-collecting systems on concentrations of tumor necrosis factor in serum and plasma. Clinical Chemistry. 1988;34(11):2373–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nold M. F., Nold-Petry C. A., Zepp J. A., Palmer B. E., Bufler P., Dinarello C. A. IL-37 is a fundamental inhibitor of innate immunity. Nature Immunology. 2010;11(11):1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor A., Verhagen J., Blaser K., Akdis M., Akdis C. A. Mechanisms of immune suppression by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-β: the role of T regulatory cells. Immunology. 2006;117(4):433–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oreja-Guevara C., Ramos-Cejudo J., Aroeira L. S., Chamorro B., Diez-Tejedor E. TH1/TH2 Cytokine profile in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients treated with Glatiramer acetate or Natalizumab. BMC Neurology. 2012;12, article 95 doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dalle-Donne I., Rossi R., Colombo R., Giustarini D., Milzani A. Biomarkers of oxidative damage in human disease. Clinical Chemistry. 2006;52(4):601–623. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.061408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Analytical Biochemistry. 1969;27(3):502–522. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker M. A., Cerniglia G. J., Zaman A. Microtiter plate assay for the measurement of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in large numbers of biological samples. Analytical Biochemistry. 1990;190(2):360–365. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90208-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papadopoulos J., Karpouzis A., Tentes J., Kouskoukis C. Assessment of interleukins IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 in acute urticaria. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research. 2014;6(2):133–137. doi: 10.14740/jocmr1645w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong C. K., Ho C. Y., Ko F. W. S., et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-17, IL-6, IL-18 and IL-12) and Th cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13) in patients with allergic asthma. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2001;125(2):177–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barbosa I. G., Morato I. B., de Miranda A. S., Bauer M. E., Soares J. C., Teixeira A. L. A preliminary report of increased plasma levels of IL-33 in bipolar disorder: further evidence of pro-inflammatory status. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;157:41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li C., Zhao P., Sun X., Che Y., Jiang Y. Elevated levels of cerebrospinal fluid and plasma interleukin-37 in patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:9. doi: 10.1155/2013/639712.639712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Felice C., Signorini C., Durand T., et al. Partial rescue of Rett syndrome by ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) oil. Genes & Nutrition. 2012;7(3):447–458. doi: 10.1007/s12263-012-0285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arango Duque G., Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5, article 491 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abbas K., Lichtman A. H., Pillai S. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. 7th. New York, NY, USA: Elsevier; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanderson C. J. Interleukin-5, eosinophils, and disease. Blood. 1992;79(12):3101–3109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Felice C., Guazzi G., Rossi M., et al. Unrecognized lung disease in classic Rett syndrome: a physiologic and high-resolution CT imaging study. Chest. 2010;138(2):386–392. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akdis M., Burgler S., Crameri R., et al. Interleukins, from 1 to 37, and interferon-γ: receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;127(3):701–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buckner J. H. Mechanisms of impaired regulation by CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in human autoimmune diseases. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2010;10(12):849–859. doi: 10.1038/nri2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolk K., Witte E., Witte K., Warszawska K., Sabat R. Biology of interleukin-22. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2010;32(1):17–31. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bourgeais J., Gouilleux-Gruart V., Gouilleux F. Oxidative metabolism in cancer: a STAT affair? JAK-STAT. 2014;2(4) doi: 10.4161/jkst.25764.e25764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kesarwani P., Murali A. K., Al-Khami A. A., Mehrotra S. Redox regulation of T-cell function: from molecular mechanisms to significance in human health and disease. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2013;18(12):1497–1534. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Milne G. L., Dai Q., Roberts L. J. The isoprostanes-25 years later. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2015;1851(4):433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Galano J.-M., Mas E., Barden A., et al. Isoprostanes and neuroprostanes: total synthesis, biological activity and biomarkers of oxidative stress in humans. Prostaglandins and Other Lipid Mediators. 2013;107:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blardi P., de Lalla A., D'Ambrogio T., et al. Long-term plasma levels of leptin and adiponectin in Rett syndrome. Clinical Endocrinology. 2009;70(5):706–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Procaccini C., Pucino V., Mantzoros C. S., Matarese G. Leptin in autoimmune diseases. Metabolism. 2015;64(1):92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ciccoli L., De Felice C., Paccagnini E., et al. Morphological changes and oxidative damage in Rett Syndrome erythrocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—General Subjects. 2012;1820(4):511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Felice C., Cortelazzo A., Signorini C., et al. Effects of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on plasma proteome in rett syndrome. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:9. doi: 10.1155/2013/723269.723269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maffei S., De Felice C., Cannarile P., et al. Effects of ω-3 PUFAs supplementation on myocardial function and oxidative stress markers in typical rett syndrome. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014;2014:8. doi: 10.1155/2014/983178.983178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Signorini C., De Felice C., Leoncini S., et al. Altered erythrocyte membrane fatty acid profile in typical Rett syndrome: effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2014;91(5):183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Calder P. C. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2015;1851(4):469–484. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.De Felice C., Signorini C., Leoncini S., Durand T., Ciccoli L., Hayek J. Oxidative stress: a hallmark of Rett syndrome. Future Neurology. 2015;10(3):179–182. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Relative changes (as fold variations) for inflammatory status, circulating cytokines, and redox status in MECP2- and CDKL5- mutated Rett patients. In order to account for real changes of the examined variables, i.e., independently of absolute basal concentrations, we performed data analysis through a double standardization (i.e., basal values of untreated MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT patients vs. control values and treated MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT patients vs. untreated) (Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2). After standardization, some differences loosed weight in both ω -3 PUFAs supplemented MECP2- and CDKL5-RTT. In particular, changes in IL-10 in MECP2-RTT and changes in IL-6, TGF-b1, IL-37, IP-10, IL-5/ TNF-α ratio, IL-6/ TNF-α ratio, IL-10/ TNF-α ratio in CDKL5-RTT were found to be not significant. Likewise, other differences gained statistical significance as changes in IL-5, IL-6/IFN-g ratio, IL-4/ TNF-α ratio, IL-6/ TNF-α ratio in MeCP2-RTT and IFN-g, IL-1b, IL-5, IL-37, IL-4/ IFN-g ratio, F4-NeuroPs, and GSH/GSSG ratio in CDKL5-RTT.