Abstract

Multiple forms of valuation contribute to public acceptance of conservation projects. Here, we consider how esthetic, intrinsic, and utilitarian values contribute to public attitudes toward a proposed reintroduction of guanaco (Lama guanicoe) in a silvopastoral system of central Chile. The nexus among landscape perceptions and valuations, support for reintroductions, and management of anthropogenic habitats is of increasing interest due to the proliferation of conservation approaches combining some or all of these elements, including rewilding and reconciliation ecology, for example. We assessed attitudes and values through an online questionnaire for residents of Santiago, Chile, using multiple methods including photo-montages and Likert scale assessments of value-based statements. We also combined the questionnaire approach with key informant interviews. We find strong support for the reintroduction of guanacos into the Chilean silvopastoral system (‘espinal’) in terms of esthetic and intrinsic values but less in terms of utilitarian values. Respondents preferred a scenario of espinal with guanacos and expressed interest in visiting it, as well as support for the reintroduction project on the basis that guanacos are native to central Chile. We suggest that reintroduced guanacos could serve as a ‘phoenix flagship species’ for espinal conservation, that is, a flagship species that has gone regionally extinct and is known but not associated with the region in the cultural memory. We consider how the lack of local cultural identity can both help and weaken phoenix flagships, which we expect to become more common.

Keywords: Anthropocene, Chile, Lama guanicoe, Landscape, Reintroduction, Rewilding, Value

Introduction

People consider nature in terms of its utilitarian, intrinsic, and esthetic values (Jepson and Canney 2003; Saunders 2013). These multiple axes of valuation are assessed both cognitively and emotionally (Edwards 1990). Esthetic values have had a particular role in the field of landscape perception, an area that has been extensively studied (e.g., Hull and Stewart 1992; Surova and Pinto-Correia 2008). Although landscape valuation studies typically only consider plant communities, wildlife-viewing experiences can add movement, surprise, or contemplative opportunities to the esthetic appreciation of landscapes (Rolston 1987; Montag et al. 2005; Gobster 2008). People also generally prefer large, colorful, and pretty animal species (Veríssimo et al. 2009), which are more likely to gain public attention and therefore to be protected, along with their habitats (e.g., Brambilla et al. 2013). Although a causal link between conservation values and conservation actions can be difficult to establish (Crites et al. 1994; Veríssimo 2013), values nonetheless must underlie any consistent, voluntary conservation behavior. Accordingly, a place will be valued differently according to its landscape- and wildlife-related features and to how they speak, emotionally and cognitively, to a specific group of people (Saunders 2013).

Species reintroductions can strongly interact with the public’s perceptions of a landscape, of the species being reintroduced, or the conservation project in question (e.g., Parsons 1998; Alagona 2004). Perceptions are evaluated as positive or negative according to different axes or categories of values; we refer to preferences being expressed for higher-valued options or outcomes (Crites et al. 1994; Jepson and Canney 2003). Esthetic valuations of reintroductions would focus on perceptions of the beauty or attractiveness of the species, the habitat, or other aspects of the program (Saunders 2013). Intrinsic valuations would be applied to ideas about inherent characteristics of the species, habitat, or program, for example, attributing a positive value to native species or high biodiversity (Soulé 1985). Finally, utilitarian valuations refer to evaluations of the usefulness of the reintroduction program, species, or habitat, in terms of benefits to humans, for example in terms of ecosystem services or contributions to economic development (Jepson and Canney 2003). In addition, evaluations of nature, and its conservation, that are utilitarian, intrinsic, or esthetic, are influenced by affective (emotional) considerations, or by rational (also called ‘cognitive’) considerations (Edwards 1990; Crites et al. 1994). In other words, emotion and rationality are methods for evaluation, and utilitarian, intrinsic, and esthetic values provide metrics, axes, or categories for evaluation. For example, conservation biologists traditionally focus on rational considerations of the intrinsic value of reintroduction programs by arguing, e.g., that ecological data show (=rational method) that a certain native species would increase the biodiversity of the ecosystem (=intrinsic value of biodiversity) if reintroduced (Soulé 1985). Equally, affective considerations and esthetic or utilitarian metrics may be used to evaluate the same native species or biodiversity outcome by other actors, or in other contexts.

In addition, reintroductions can provide important socio-economic benefits. Reintroduced species can become conservation symbols (e.g., Seddon and van Heezik 2013); they can be used as an educational tool (e.g., Aveling and Mitchell 1982); and they can have direct economic, particularly touristic, assets (e.g., Montag et al. 2005). The way people evaluate these symbols, programs, or tangible benefits may be based on esthetic and utilitarian values as well as intrinsic ones, and on affective as well as rational considerations. With increasing attention and action dedicated to rewilding, restoration ecology and reconciliation ecology, and other approaches to managing contemporary anthropogenic landscapes (Navarro and Pereira 2012; Kueffer and Kaiser-Bunbury 2013; Seddon and van Heezik 2013), the overlap between reintroductions, flagship species uses, and landscape perceptions lies at a critical area of cutting-edge conservation practice.

The reintroduction of guanacos (Lama guanicoe) to a silvopastoral habitat of central Chile provides an interesting case study of interactions between public perceptions of conservation goals, landscapes, and species. Central Chile, the only mediterranean-like ecosystem of South America, has a high biodiversity and endemicity rate (Simonetti 1999; Myers et al. 2000). However, compared to the scenic and natural resource-rich north and south of Chile, silvopastoral and other anthropogenic mediterranean-climate landscapes of central Chile are generally perceived as less important to economic development and less beautiful (Fuentes et al. 1984; de Val et al. 2004; Root-Bernstein and Armesto 2013). Central Chilean habitats range from sclerophyllous forests and shrub habitat (matorral) to savanna-like silvopastoral systems called ‘espinal’ (Armesto et al. 2010). A history of unsustainable management practices (Aronson et al. 1993) contributes to a local association of central Chile, and espinals in particular, with rural poverty and environmental degradation (Root-Bernstein 2014). These factors might explain why central Chile has the lowest protected area coverage and conservation effort within Chile (Pauchard and Villarroel 2002). Root-Bernstein and Armesto (2013) propose a ‘flagship fleet’ to improve awareness of the conservation value of central Chile, composed of eight species, including small and medium sized mammals, birds, reptiles, invertebrates, and trees. The flagship fleet approach might overcome the absence of a large and unequivocally charismatic animal in the region. Another approach to the flagship gap would be to reintroduce such a species.

Currently, a project is underway at the private Nature Reserve Altos de Cantillana, central Chile, to reintroduce guanaco as a natural restoration tool in espinals (Root-Bernstein et al. in prep.). Guanacos were extirpated from central Chile around 500 years ago (Miller 1980). Although considered of Least Concern (LC) for the IUCN Red List, they have been classified as vulnerable at a national level and are being reintroduced into various areas of Chile under a national management plan (Grimberg Pardo 2010). National guidelines for guanaco conservation and productive exploitation (e.g., for wool) already exist (Iriarte 2000). Guanacos have proven to be economically valuable from a touristic perspective (Franklin et al. 1997), and for meat (Skewes et al. 2000) and wool production (Montes et al. 2006; Irarrázabal 2008). In pre-Columbian times, camelids had a strong cultural and mythological importance among indigenous communities throughout the Andean region (Garrido Escobar 2010). Although this particular cultural connection to camelids has been lost in central Chile today, more recently guanacos have been described as the “wildlife icon of South America” (Novaro 2010). Thus, according to our hypothesis that landscape and wildlife related features interact to affect how people value reintroduction projects, we make two predictions. First, the presence of guanacos should improve valuations of the espinal landscape. Second, if the first prediction is true, then the reintroduction of guanacos into espinal should be positively evaluated. We investigate whether these predictions will be supported primarily on the basis of utilitarian values (ecological restoration, economic benefits), intrinsic values (native and endangered species, regional/historical cultural value), or esthetic values (charismatic species, landscape appreciation), and whether mainly through rational or affective considerations. We then consider whether the guanaco has potential as a flagship species for restoration and conservation in espinals.

Materials and methods

Fieldwork was carried out in Santiago de Chile in June and July 2013. We used a mixed-method approach including qualitative unstructured and semi-structured key-informant interviews and a quantitative self-administered online questionnaire (e.g., Kempton et al. 1995; Bardsley and Edwards-Jones 2006).

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with key informants identified through snowballing and involved in scoping and setting up the initial guanaco reintroduction (a process independent of this paper; the reintroduction took place in July 2014). They include a forestry engineer, an employee of CONAF (state forestry department, which is in charge of conservation), a guanaco expert from a major Chilean university, an espinal agronomer from a major Chilean university, a conservation expert from a major Chilean university, the directors of two international conservation NGOs working in Chile, the owner of the private reserve Altos de Cantillana (where guanacos were reintroduced), and a local entrepreneur working in ecotourism. We were not able to interview the director of Proyecto Wanaku, an initiative of the meat producer Sopraval, which pastures several dozen guanacos in an espinal in order to harvest their wool. However, we consulted published interviews with her, available from their website (Irarrázabal 2008). All interviews were conducted in Spanish, in person and lasted between 15 and 60 min each.

Separately, unstructured interviews were conducted with various Chileans to whom a draft questionnaire was administered, in order to confirm or reject the assumptions underpinning each question, following Kempton et al (1995). The final version of the quantitative questionnaire was implemented according to the results from these interviews.

The quantitative questionnaire was online based and was distributed exclusively to inhabitants of Santiago de Chile (which is in the center of central Chile). We used a sampling frame targeting middle-upper class dwellers of Santiago, with a variable engagement with nature-related topics, for which we have a comparative baseline of nature-related attitudes (Root-Bernstein and Armesto 2013; Root-Bernstein 2014). This urban, higher-income, higher-education group also represents people with economic, social, and political influence over conservation and development issues in central Chile, through local tourism, investment, and access to centralized policy-making positions. Respondents were targeted through personal contacts, requests for email forwarding, posts on social media, and maillists of individuals with some professional or personal interest in nature. The open-ended nature of this sampling frame means that we were unable to calculate the response and non-response rates, since the actual number of people who saw or received the questionnaire link is not known.

Structure of the questionnaire

The duration of the questionnaire was approximately 10–15 min. It included 21 questions (Q01–Q21), plus some generic profile information about the respondent (G01–G06). The types of questions included hierarchical ranking of elements, 1-to-10 scale scores, Likert-scale ratings, Yes/No questions, multiple choices, and open-ended questions. For the majority of the questions, a ‘No opinion’ option was available, in order to discourage forced answers. Several questions were photo-based (Q01, Q05, Q09, Q10). Although they only give a static representation of a scene and do not include perceptions by other senses, visualization techniques permit control over other environmental variables (e.g., light, cloud cover), which may shape the experience of the visitor in-situ (Surova and Pinto-Correia 2008).

The questionnaire was subdivided into five independent sections. Respondents were not allowed to read the following section before having completed the previous one. We first assessed respondents’ attitudes toward nature (Section 1: Q01–Q04). Q01 assessed the esthetic attraction of a set of species considered representative of different categories of animals: hawks (native and visible in espinal), pumas (native and rare in espinal), sheep (agricultural symbolism, frequently visible in espinals), and reindeer (non-native, not appropriate to the ecosystem, and thus a control for native status and presence in espinal). These were shown with neutral backgrounds (e.g., sky). Q02 looked at the valuation of central Chile compared to other Chilean regions and Q03 the valuation of semi-natural landscapes compared to other types of landscapes. Q04 gaged Chilean cultural similarities with Europe but was omitted from analysis.

Section 2 considered perceptions and knowledge of espinal (Q05–Q08). This included assessing its esthetic value (Q05), the adjectives associated to the landscape (Q07), and providing self-generated answers for the species considered typical of the espinal (Q08). Q06 asked if respondents recognized and knew the name of a photograph of espinal.

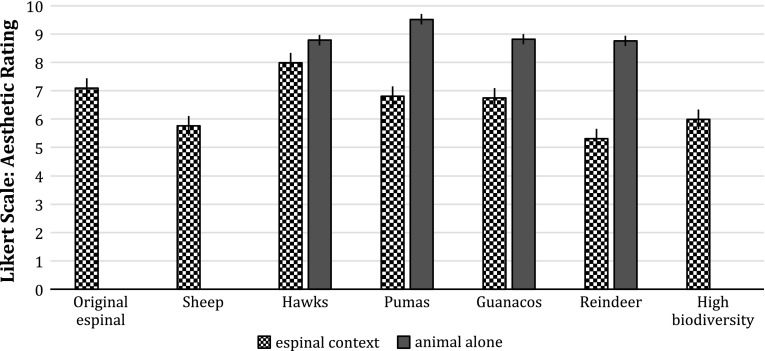

In the third section, the reintroduction project was approached from an affective perspective (Q09–Q10). We compared photo montages of various animals in an espinal: guanacos, hawks, pumas, sheep, and reindeer, and one with all these animals together (high biodiversity scenario) (Fig. 1). For each landscape, respondents were asked to express an esthetic valuation on a 1-to-10 scale (Q09). The landscape with guanacos was then directly compared to the original animal-free image of the espinal (Fig. 1), to determine which one was (i) generally preferred, (ii) considered more esthetically valuable, and (iii) more interesting to visit (Q10). This section was put before Section 4 in the questionnaire in order to avoid biases toward guanacos.

Fig. 1.

Above, the original image of espinal without wildlife. Left to right, top to bottom: with hawks, with sheep, with guanacos, with reindeer, with puma and the ‘high biodiversity’ scenario

The fourth section (Section 4: Q11–Q15) focused on guanacos. Some adjectives associated to guanacos (Q13) and its geographic connotation (Q14) were assessed. Respondents’ relationship with the animal was evaluated, both in terms of visual observation (Q11), visual recognition (Q12), and biogeographical knowledge (Q15).

The guanaco reintroduction project was then assessed from a rational dimension (Section 5: Q16–Q21). Information about the reintroduction was presented, framed as a set of cumulative hypotheses that would progressively enhance respondents’ rational knowledge of the project. This was done to determine how opinions about the project would be shifted by adding information, which would consequently highlight which values are coming into play. In Q16, the project was described as an ‘introduction’; thus, no reference to the past native status of the animal was provided. In Q18, the statement that guanacos are native but recently disappeared was mentioned. In Q20, the utilitarian value of the species was explained, both ecologically and economically. For each new piece of information concerning the project, respondents were asked to rate on a 1-to-10 scale, their appreciation of the project, and to what extent they agreed with a set of statements (Q17, Q19, Q21).

The last section concerned respondent profile questions about their relationship to nature and social background (G01–G06). These included age, gender, level of education (optional), profession (optional), visit frequency to natural places and to the espinal, and nature-related hobbies (bird-watching, nature-photography, and hiking). This part was used to categorize the sample into several groups for the analysis (see Analysis and Indices).

Analysis and indices

Indices and profile factors were used to better characterize and account for any biases in relevant interest, knowledge, or background in our respondent sample which was self-selecting and thus unlikely to be a random sample.

Three indices were developed, each composed of two groups separated by the value of the median, with group 1 having the lower values (see Table 1). Index-N was intended as a way to quantify respondents’ engagement with nature and included the frequency with which the respondent visits nature, goes hiking, goes bird-watching, and does nature-photography, the last two hobbies being common ways in which many residents of Santiago interact with nature (Root-Bernstein 2014). Similarly, Index-G was intended as a way to determine respondents’ interaction with guanacos and includes the type of observation, the degree of recognition, and some biogeographical knowledge. Finally, Index-E was created to assess the degree of knowledge of the espinal, both in terms of recognition and frequency of visit. Although Index-G revealed itself to be significantly different from the two other indices (χ2 test of association, P = 0.775 with Index-N and P = 0.886 with Index-E), Index-E and Index-N were correlated (χ2 test of association, P < 0.001). The age variable included a ‘younger’ group and an ‘older’ group. The education level variable was composed by a ‘lower education’ group (incomplete university degree or less) and a ‘higher education’ group (complete university degree or more). The gender variable included men and women.

Table 1.

Explanation of the creation of the indices used for the analysis

| Index | Parameter | Descriptive statistics | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Frequency of visit to natural places (question G05a) | 0 → 2 | |

| Frequency of hiking (G06a) | 0 → 2 | ||

| Frequency of nature—photography (G06b) | 0 → 2 | ||

| Frequency of bird—watching (G06c) | 0 → 2 | ||

| G05a + G06a + G06b + G06c | 0 → 8 | ||

| Lower Group: Index-N(1) | n = 96 | 0 → 4 | |

| Higher Group: Index-N(2) | n = 102 | 5 → 8 | |

| Median = 5 | |||

| G | Previous encounters with guanacos (Q11) | 0 → 3 | |

| Recognition of guanacos (Q12) | 0 → 2 | ||

| Biogeographical knowledge (Q15) | 0 → 3 | ||

| 2*Q11 + 3*Q12 + 2*Q15 | 0 → 18 | ||

| Lower Group: Index-G(1) | n = 87 | 0 → 13 | |

| Higher Group: Index-G(2) | n = 111 | 14 → 18 | |

| Median = 14 | |||

| E | Frequency of visit of the espinal (G05b) | 0 → 2 | |

| Recognition of the espinal (Q06) | 0 → 2 | ||

| G05b + Q06 | 0 → 4 | ||

| Lower Group: Index-E(1) | n = 91 | 0 → 2 | |

| Higher Group: Index-E(2) | n = 107 | 3 → 4 | |

| Median = 3 |

Description of the indices created to characterize the respondent sample

Index-N was used to explain answers to the section on nature in Chile (Section 1), Index-E for the section on espinals (Section 2), and Index-G for the section on guanacos (Section 4). For Sections 3 and 5, all the indices and profile factors except Index-E (not significantly different from Index-N, see above) were tested. Where necessary, the thresholds of the P values were adjusted by using the False Discovery Rate (FDS) method to control familywise error rates (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). The P values obtained and used for each question are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The P value thresholds used for the analysis of each question of the survey

| Section | Question | Explanatory variables tested | Number of significant tests (with a P value threshold of 0.05) | New P value (=0.05/number of significant tests—Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1 | Q01, Q02, Q03, Q04 | Index-N | ≤1 | Unchanged (0.05) |

| Section 2 | Q05, Q06, Q07, Q08 | Index-E | ≤1 | Unchanged (0.05) |

| Section 4 | Q11, Q12, Q13, Q14, Q15 | Index-G | ≤1 | Unchanged (0.05) |

| Section 3 | Q09 (sheep) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 1 | Unchanged (0.05) |

| Q09 (hawk) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q09 (guanaco) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 2 | 0.025 | |

| Q09 (reindeer) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q09 (puma) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q09 (biodiversity) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q10 (preference) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q10 (esthetic) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 1 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q10 (visit) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 1 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Section 5 | Q16 | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 1 | Unchanged (0.05) |

| Q17 (beauty espinal) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q17 (attractive animal) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q17 (economic benefits) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 1 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q17 (weird there) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 3 | 0.01667 | |

| Q17 (identity loss) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 3 | 0.01667 | |

| Q17 (ethically debatable) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 2 | 0.025 | |

| Q18 | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 2 | 0.025 | |

| Q19 (moral responsibility) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 3 | 0.01667 | |

| Q19 (accept extinction) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 2 | 0.025 | |

| Q19 (not same habitat) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 1 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q19 (economic benefits) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 1 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q20 | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q21 (enhance opinion central Chile) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 2 | 0.025 | |

| Q21 (frequency visit espinal) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) | |

| Q21 (guanaco symbol espinal) | Index-N, Index-G, Age, Sex, Education | 0 | Unchanged (0.05) |

Except for one question, answers did not have a normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, P < 0.05), and attempts of parameterization of the datasets failed. Hence, all the tests used for the analysis of the questionnaire were non-parametric tests. The questionnaire was analyzed with a statistical package (IBM SPSS Statistics 21). The outputs from the questionnaire were integrated, when relevant, with those from the qualitative interviews to provide confirming or contrasting views lending themselves to a more in-depth understanding of the issues.

Results

The questionnaire was distributed via links and email forwarding; thus, we cannot be sure of the actual response rate. 198 people successfully responded to the whole questionnaire between 19 June and 13 July 2013. Added to this number, another 120 respondents started answering the questionnaire but did not complete it and were thus excluded from the analysis. The sample includes 90 men and 108 women. The mean age of the respondents is 29.81 and the level of education relatively high (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Categorization of the sample

| Category | N | Total | Index name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Men | 90 | Men | |

| Women | 108 | Women | |

| Education | |||

| Incomplete high school | 4 | 77 | Lower education group (Education-1) |

| Complete high school | 11 | ||

| Incomplete university degree | 62 | ||

| Complete university degree | 85 | 121 | Higher education group (Education-2) |

| Postgraduate degree | 36 | ||

| Age (years old) | |||

| Mean = 29.81 | |||

| Median = 26 | |||

| 102 | Younger group: 0–26 (Age-1) | ||

| 96 | Older group: >26 (Age-2) | ||

In brackets are the names of the groups for the analysis. Likewise for the creation of the indices, the identification of age-groups stems from the median in order to have numerically similar groups

Section 1: Chilean people and nature

Respondents had a high esthetic appreciation of the four animals that were shown without a landscape background, with a particularly high score given to the puma (9.52 out of 10) and rather high scores given to the guanaco (8.82), the hawk (8.78), and the reindeer (8.76) (for statistics see Q1, Table 4). Scores were significantly higher in Index-N(2) than in Index-N(1) for the three native species (Mann–Whitney; hawk: U = 3512, P < 0.001; puma: U = 4118.5, P = 0.007; guanaco: U = 3661, P < 0.001; reindeer: U = 4149, P = 0.039).

Table 4.

Statistical tests not shown in the text. Significant P values are shown in bold (see Table 3). Questions are shown in the order they appear in ‘Results’

| Question | Test | df | Test statistic | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Wilcoxon | Puma–guanaco: Z = −5.916 | <0.001 | |

| Guanaco–hawk: Z = −0.263 | =0.792 | |||

| Hawk–reindeer: Z = −0.039 | =0.969 | |||

| Q2 | Wilcoxon | South–north: Z = −10.435 | <0.001 | |

| North–center: Z = −2.247 | =0.025 | |||

| Q3 | Wilcoxon | National park–coast: Z = −7.843 | <0.001 | |

| Coast–countryside: Z = −3.888 | <0.001 | |||

| Countryside–city: Z = −10.724 | <0.001 | |||

| Q6 | χ 2 | Wild: 1 | χ 2 = 26.672 | <0.001 |

| With livestock: 1 | χ 2 = 105.190 | <0.001 | ||

| Agricultural: 1 | χ 2 = 52.769 | <0.001 | ||

| Full of wildlife: 1 | χ 2 = 4.170 | =0.041 | ||

| Productive: 1 | χ 2 = 8.889 | =0.003 | ||

| Q13 | χ 2 | Wild: 1 | χ 2 = 97.163 | <0.001 |

| Aggressive: 1 | χ 2 = 69.871 | <0.001 | ||

| Rare: 1 | χ 2 = 34.351 | <0.001 | ||

| Threatened: 1 | χ 2 = 5.114 | =0.024 | ||

| Q14 | Wilcoxon | South American-Andean: Z = −0.853 | =0.393 | |

| Andean-Chilean: Z = −6.560 | <0.001 | |||

| Chilean-Bolivian: Z = −2.306 | =0.021 | |||

| Bolivian-Patagonian: Z = −2.133 | =0.033 | |||

| Q9 | Wilcoxon | Espinal–espinal with hawks: Z = −5.726 | <0.001 | |

| Espinal–espinal with puma: Z = −0.632 | =0.527 | |||

| Espinal–espinal with guanaco: Z = −0.836 | =0.403 | |||

| Espinal–espinal w/ biodiversity: Z = −3.594 | <0.001 | |||

| Espinal–espinal with sheep: Z = 5.664 | <0.001 | |||

| Espinal–espinal with reindeer: Z = −6.370 | <0.001 | |||

| Q10 | χ 2 | Image preference: df = 2 | χ 2 = 46.455 | <0.001 |

| Esthetic value: df = 2 | χ 2 = 79.121 | <0.001 | ||

| Interest to visit: df = 2 | χ 2 = 118.303 | <0.001 | ||

| Q17 | χ 2 | Ethically debatable: df = 1 | χ 2 = 33.333 | <0.001 |

| Identity loss: df = 1 | χ 2 = 6.968 | =0.008 | ||

| Economic benefits: df = 2 | χ 2 = 4.450 | =0.035 | ||

| Attractive animal: df = 1 | χ 2 = 82.672 | <0.001 | ||

| Weird there: df = 1 | χ 2 = 2.752 | =0.109 | ||

| Beauty espinal: df = 1 | χ 2 = 0.132 | =0.716 | ||

| Q19 | χ 2 | Moral responsibility: df = 1 | χ 2 = 23.259 | <0.001 |

| Accept extinction: df = 1 | χ 2 = 7.158 | =0.007 | ||

| Economic benefits: df = 1 | χ 2 = 112.978 | <0.001 | ||

| Not same habitat: df = 1 | χ 2 = 16.176 | <0.001 | ||

| Q21 | χ 2 | Enhance opinion: df = 1 | χ 2 = 6.153 | =0.013 |

| Frequency of visit: df = 1 | χ 2 = 9.302 | =0.002 | ||

| Symbol of espinal: df = 1 | χ 2 = 5.050 | =0.025 |

The South of Chile was the most appreciated in terms of landscapes followed by the north and the center (Q2, Table 4). There were no significant differences within Index-N (Mann–Whitney; north: U = 4781.5, P = 0.753; center: U = 4798, P = 0.782; south: U = 4894.5, P = 0.995). This particular attachment to the wilderness lands of the South and the general dislike of central Chile was pointed out by the majority of the key informants. When questionnaire respondents were asked to rank the type of destinations they would choose for their holidays, ‘natural parks’ emerged as the most preferred followed by ‘coastal areas,’ ‘semi-natural areas/countryside,’ and finally ‘cities’ (Q3, Table 4). The rank given to ‘natural parks’ by those belonging to Index-N(2) (mean = 1.21) was significantly higher than those of group Index-N(1) (mean = 1.52) (Mann–Whitney, U = 3922.5, P = 0.002).

Section 2: Espinal

The mean esthetic rating of espinal was 7.10 out of 10 (SD = 1.885). Index-E did not explain any difference in esthetic valuation of espinal (Mann–Whitney, U = 4395, P = 0.232).

The espinal was perceived as ‘wild’ (68.8 % agreed with this statement) and ‘with livestock’ (87.3 % agreed), but not as an ‘agricultural’ place (23.1 %). The statements that espinals are ‘full of wildlife’ (42.6 % agreed) and ‘productive’ (38.9 %) were rejected by the majority (Table 4 (Q6)). This was confirmed by two key informants, who asserted that ‘espinals have a bleak connotation to me; they are neither natural nor humanized. There is no production, no humans, no wildlife,’ and ‘there is an urgent need to turn the espinal into a more productive and economically more valuable landscape.’ However, a higher knowledge of the espinal significantly increased the percent agreement with the statement that espinals contain wildlife (Mann–Whitney, U = 3604, P = 0.019).

Out of the 192 respondents who provided an answer, 31.7 % were not able to name a typical animal species in the espinal, while the most cited one was the non-native rabbit (9.4 %). According to the director of one NGO, in fact, ‘in Chile there is no common ground knowledge of what is native, mainly due to the brutal effects of European colonization.’ Nevertheless, the native/non-native ratio significantly increased with Index-E(2) (Mann–Whitney, U = 587, P < 0.001). In addition, among those who could provide an answer, the proportion of those naming a bird significantly increased for Index-E(2) (Mann–Whitney, U = 1530.5, P = 0.027).

For plants, although 22.4 % of respondents could not name any typical plant species in the espinal, the most cited one (60.4 %) was the espino (Acacia caven), followed by much less cited species such as the litre (Lithreae caustica) or non-specific cactus (both 1.6 %). The majority of the plants named is indeed found in the espinal (99.3 %, n = 145) and is predominantly trees (89.0 %, n = 145) and wild plants (99.3 %, n = 139). Assuming that Acacia caven should be considered native (see Root-Bernstein and Jaksic 2013), almost all of the cited plants are native species (99.3 %, n = 139). No significant differences existed within Index-E.

Section 3: Guanacos

The animal was recognized by 81.3 % of the respondents (+16.2 % who were unsure), and no one claimed that they had never seen it (68.2 % saw it in the wild, 25.8 % only in captivity and 6.1 % only in pictures or videos). Guanacos were seen as ‘wild’ (85.2 % agreed) and were not considered ‘aggressive’ (19.4 % agreed). They were also perceived as ‘rare’ by 71.2 % of the respondents and ‘threatened’ by 58.5 % of the sample (Q13, Table 4). No significant differences emerged for Index-G.

Guanacos were primarily perceived as ‘South American’ and ‘Andean’ animals, with no significant difference between the distribution of opinions, followed by ‘Chilean,’ then ‘Bolivian,’ and, finally, ‘Patagonian’ (Q14, Table 4). For each response, there were no significant differences within Index-G. Although more than one key informant (e.g., forest engineer, an NGO director) asserted that guanacos have a strong association to Southern Chile, where the largest population is found, this was not reflected in the questionnaire. This may be explained by the conservation expert who claimed that ‘many people do not really know guanacos and their distribution.’

Section 4: Photo-modified scenarios

Respondents rated the esthetic attractiveness of the six photo-modified landscapes (Fig. 1) significantly differently. The espinal-with-hawks scenario was the most appreciated and the only one with a significantly higher value than the original image of the espinal as rated in Section 2 (Q9, Table 4). Both the espinal-with-pumas version and the espinal-with-guanacos version were not scored significantly differently than the original espinal (Q9, Table 4). The espinal-with-high-biodiversity and the espinal-with-sheep scenarios were both scored significantly less than the scenario with guanacos (Q9, Table 4). The least appreciated scenario, scored significantly less than the one with sheep, was the espinal-with-reindeer scenario (Q9, Table 4) (see Fig. 2). Interestingly, by comparing the score given to these animals in an espinal context with the same animals shown individually (Q01, Section 1), we notice that scores are significantly lower when animals are surrounded by espinal (Wilcoxon, hawk: Z = −4.322; puma: Z = −10.35; guanaco: Z = −8.162; reindeer: Z = −10.173, all P < 0.001), especially for the reindeer, symbolically and biogeographically the least related to the espinal (Fig. 2). By looking at the five explanatory variables (Index-N, Index-G, Age, Gender, Education), the only interesting pattern emerged from the age variable, whereby the older group of respondents appreciated the landscape with guanacos significantly more (Mann–Whitney, U = 3954.5, P = 0.018).

Fig. 2.

Mean responses across three different questions. Left in gray, original rating of espinal landscape (Q5). Left to right, in gray, rating of espinal images with wildlife (Q9). In black, ratings of esthetic value of each animal without the espinal context, for comparison (Q1). Error bars show the SE

When respondents were asked to directly compare the original image of an espinal without wildlife with the espinal-with-guanacos version (Q10), a significant majority of the respondents said that the version with guanacos was the one they preferred (55.6 %), that they thought it had a higher esthetic value (63.1 %) and that they would be more interested to visit it (69.7 %) (see Table 4, Q10; Fig. 3). With regard to the indices, the scenario with guanacos was preferred significantly more by the older age group than by the younger (Mann–Whitney, U = 4137, P = 0.029), considered significantly more esthetically pleasing by Index-N(2) than Index-N(1) (Mann–Whitney: U = 3968, P = 0.007), and likely to be visited with more interest by Index-G(1) than Index-G(2) (Mann–Whitney: U = 4066.5, P = 0.019).

Fig. 3.

Percent of responses for each question, showing which scenario was preferred in general, for its esthetic value in particular, or in terms of interest for visiting

Section 5: Reintroduction project

When the hypothetical project was merely described as an introduction (Q16), and no references to the previous native status of guanacos in central Chile were made, the general agreement with the project was low (mean = 3.65 out of 10, SD = 2.992). Among profile factors, the only statistically relevant pattern emerged from gender, whereby men evaluated the introduction more highly than women (4.17 vs. 3.22, Mann–Whitney, U = 3939, P = 0.023). When trying to determine what motivations might underpin their score, we see that the majority of the sample (70.8 %, see Q17, Table 4) would consider this introduction ‘ethically debatable,’ and this was particularly pronounced for women (81.4 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3558, P = 0.001) and young people (78.8 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3847.5, P = 0.013). Then, it seemed that the presence of this animal would entail a ‘loss of identity’ of the espinal (59.7 %, Q17, Table 4), particularly for the older group (68.0 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3643, P = 0.029). In terms of utilitarian values, the hypothesis that the introduction would be positive ‘if it provided economic benefits’ was rejected by the majority of respondents (42.3 % agreement with this statement; Q17, Table 4), and even more by women (33.7 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3617, P = 0.010). Interestingly, only a small minority of the respondents thought that guanacos would be ‘the only attractive animal found in the espinal’ (16.9 %; Q17, Table 4). Finally, both the statements ‘it would be weird to see guanacos there’ (55.9 %) and ‘the presence of guanacos would enhance the beauty of the espinal’ (51.3 %) were contested and did not provide any significant majority response (Q17, Table 4). However, the latter statement was significantly approved by the group with higher education (59.0 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3366, P = 0.007). No significant patterns were observed within Index-N nor Index-G.

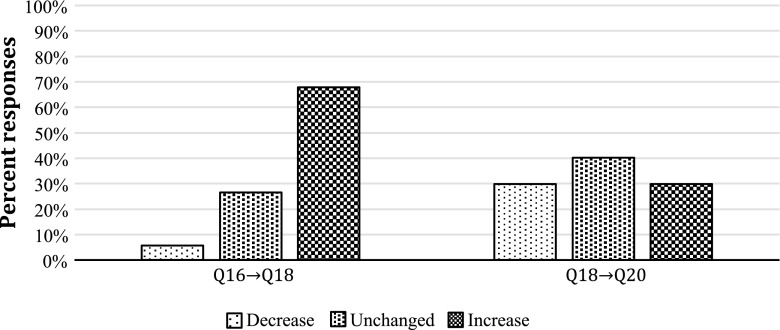

When, in the following set of questions, the precolumbian native status of guanacos was mentioned and when, accordingly, the project was described as a ‘reintroduction,’ its appreciation increased significantly (mean = 5.93 out of 10, SD = 3.069, +2.28, Wilcoxon, Z = −9.262, P < 0.001). There were in fact 133 respondents (67.9 %) that increased their score, and only 11 (5.6 %) who gave a lower score (Fig. 4). The ‘older’ group (Age-2) seemed to agree significantly more with the reintroduction than the ‘younger’ group (Age-1) (6.59 vs. 5.32, Mann–Whitney, U = 3630, P = 0.003). If we look at the motivations behind it, the majority of the respondents considered that reintroducing guanacos in part of their former range is a ‘moral responsibility’ (67.4 %, Q19, Table 4), and this was particularly true for those with higher education (74.4 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3655.5, P = 0.010). Likewise, the majority of the sample size rejected the statement that ‘we should accept extinction as part of a natural process’ (40.3 % agreed with this statement, Q19, Table 4), and this was significantly more pronounced for the older group (29.0 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3555, P = 0.002) and for the higher education group (30.7 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3342.5, P = 0.001). Moreover, the great majority of respondents rejected the idea that the important criteria to consider are the ‘economic benefits brought by the reintroduction,’ rather than the native status of guanacos in central Chile (89.5 %, Q19, Table 4), a statement which was refuted even more strongly by those with higher Index-N (92.9 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3661.5, P = 0.033). Finally, 64.7 % of the respondents agreed with the statement that the current espinal ‘cannot be considered the same landscape’ as the one in which guanacos probably used to live in the past (Q19, Table 4), and no significant patterns emerged from the indices.

Fig. 4.

Percent of respondents expressing more, less, and equal support for the project between sections where it was described as an ‘introduction’ of guanacos and then a ‘reintroduction’ (left) and between that section and when it was described as having economic benefits (right)

When the potential future economic benefits of this reintroduction were emphasized, respondents said that they would agree with the project with a mean score of 5.74 out of 10 (SD = 3.076), which was not significantly different than the score given in the description of the project as a morally based reintroduction (Q18) (−0.19, Wilcoxon, Z = −0.815, P = 0.415). In fact, 40.2 % (n = 78) of the respondents did not change their score and, symmetrically, both 29.9 % (n = 58) increased and decreased their score (Fig. 4). No significant difference emerged from the analysis of the five indices.

Finally, a significant majority of the respondents agreed with the three final statements that were shown to them concerning the possible consequences of an espinal with guanacos. Firstly, a significant majority of the respondents thought that this would enhance their overall appreciation of landscapes in central Chile (Table 4, Q21), which goes alongside with the opinion of the forest engineer, when he declared that ‘the presence of guanacos could improve the perception that people have of this region.’ Nevertheless, several respondents claimed, in email correspondence after having completed the questionnaire, that the lack of valorization of central Chile is more a cultural problem and should accordingly be tackled with educational tools rather than by reintroducing one single charismatic species. This cultural issue was emphasized with insistence by an NGO director, who argued that ‘there is a remarkable lack of awareness concerning nature in central Chile, which goes beyond the size or the quality of the species that can be found there […] Although the presence of guanacos might help, it is probably not enough to recover five centuries of deep unawareness concerning this topic,’ and that ‘there is an urgent need of creativity and education to resolve this issue.’ Secondly, a significant majority of the sample believed that they would be more interested in visiting espinal if there were guanacos in it. This result is in line with the opinion of the CONAF employee, the owner of the Altos de Cantillana reserve, the eco-tourism entrepreneur, and the director of the ‘Proyecto Wanaku’ initiative (Irarrázabal 2008), who expected that the presence of guanacos would enhance tourism in the area where they were reintroduced. Thirdly, a significant majority of the interviewees (58.4 %, Table 4, Q21) agreed with the statement that guanacos could become the new symbolic animal of the espinal. This was strongly endorsed by one NGO director, since he/she argued that ‘in central Chile there is a lack of “sexy” animals that can easily appeal to people, therefore guanacos might play an important role in terms of potential flagship species.’ The only significant pattern among the variables was given by the older group (Age-2) which was more likely to experience an improved perception of espinals if there were guanacos there than the younger group (Age-1) (69.0 %, Mann–Whitney, U = 3172.5, P = 0.010).

Discussion

Guanaco reintroduction into espinal was broadly supported by respondents and key informants. Human-wildlife conflicts, at least with tourists and highly educated groups interested in nature, should be low—but the views of locals also need to be studied. Confirming previous studies, we find that the comparative and baseline landscape appreciation of central Chile is currently low (Fuentes et al. 1984; de Val et al. 2004; Root-Bernstein and Armesto 2013; Root-Bernstein 2014). People in our sample, as in other populations, are attracted by large, supposedly charismatic species, of which the guanaco was one (Leader-Williams and Dublin 2000). We also find that animals have a strong cultural and contextual connotation linking them to certain landscapes (see Teel et al. 2007). For example, the reindeer, used here as a control for the affective assessment of esthetic value, lacks an association to espinal and the reindeer-espinal combination received a low esthetic rating. Although the guanaco is also not currently associated with the espinal landscape, the guanaco-espinal combination was esthetically appreciated. We suggest that this could be influenced by the guanaco’s intrinsic value as a Chilean native species and well-known symbol of wilderness.

There were a number of surprising findings, particularly in the photo-montage based questions probing affective assessments of esthetic values. For example, the relatively high esthetic score for espinal alone may reflect the fact that the image used is of an espinal in good condition, rather than a degraded one as apparently used in previous landscape perception studies (e.g., Fuentes et al. 1984). By contrast, the expectation that a landscape with abundant and diverse charismatic animals is esthetically more valued than the same wildlife-free one (Soulé 1985; Redford et al. 2013) is not entirely supported, as indicated by the low rating of the high biodiversity scenario. We also observed that respondents score the same images differently depending on whether they are shown in direct comparison or not (Tversky and Kahneman 1981), i.e., the guanaco-in-espinal image was preferred to the espinal image in direct comparison, but not when comparing separate questions. Some of our contradictory results also show that an affective evaluation can give a different outcome than attempting to elicit a more rational evaluation, consistent with observations that both affect and rationality contribute differently to attitudes across contexts (van den Berg et al. 2006; Gifford and Sussman 2012). Visual and text-based questions can also affect responses differently, as they approximate different sensorial and cognitive inputs to perceptions of nature. This emphasizes the complexity of determining attitudes to nature and how they will affect action beyond the questionnaire context.

The role of shifting baselines and cultural memory in shaping support for species reintroductions and landscape restoration was also evident (Papworth et al. 2009; Toledo et al. 2011). The public appears to be largely unaware of the historical baseline of guanaco and espino populations coexisting in central Chile. Nevertheless, we find that the cultural memory baseline is open to adjustment via framing with different narratives and information. Although knowledge of native animals in the espinal is low, the symbolic, inherent value of nativeness contributes to an ethical basis of support for the reintroduction project. Although recently much attention has been given to the utilitarian values of biodiversity and ecosystems (MEA 2005), here utilitarian arguments did not improve the overall evaluation of guanaco reintroduction. In agreement with other studies, we find that this strong ethical basis appears to be more pronounced in higher educated people and in women (Gifford and Sussman 2012). Overall, people with strong moral values relating to nature are thought to be more likely to engage in environmentally friendly actions than those driven by utilitarian values (Clayton 2012).

Landscape preferences and attitudes to wildlife may not always interact positively. Charismatic animals in a given landscape do not necessarily add esthetic value if the species is seen as ‘not belonging’ (Jepson and Canney 2003; Barua et al. 2011). However, this study suggests that if a species remains known within the culture, it can serve to improve landscape appreciation. Drawing on Ladle and Jepson (2008)’s concept of phoenix extinction, in which apparently extinct species are recovered, we refer to ‘phoenix-flagship species’ as all those species which are reintroduced in an area of their former range and whose presence is used as a flagship species to promote conservation actions.

The conditions under which phoenix flagships could be used are likely to become more common in the future (Navarro and Pereira 2012; Seddon and van Heezik 2013). We expect phoenix flagships to differ from the typical model of flagship species in at least two ways. First, phoenix flagships may be easy to justify with reference to baselines but are likely to present more freedom for reframing within conservation narratives due to a lack of cultural continuity. Secondly, phoenix flagships will tend to carry out their various functions (Barua et al. 2011) for novel and perhaps controversial conservation approaches. They will thus play critical roles in communicating and creating the future of conservation. Phoenix flagships will serve not only local roles, but will also symbolize the transformations of past environments into a range of anthropogenic and rewilded landscapes.

Conclusions

Our results support our prediction that guanacos can improve the esthetic perception and affective evaluation of espinal. In turn, the reintroduction of guanacos into espinal was supported from a rational perspective mainly on intrinsic rather than utilitarian grounds. The mere presence of guanacos in espinals is unlikely to reverse what some key informants described as a strong cultural bias against the valorization of central Chilean nature. However, guanacos could add esthetic and intrinsic value to the landscape if integrated into environmental education. Reintroductions of guanacos, were they to take place, could put the implications of our results into practice by taking place in visible, visitable places, with outreach to the studied demographic emphasizing the rational-intrinsic ethical arguments and affective-esthetic cultural dimensions of the reintroduction.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to U. Roll, M. Zanuso, and B. Barca for advice and technical assistance. We also thank the key informants for their participation. This research was supported by FONDECYT grant No. 3130336.

Biographies

Adrien Lindon

is a recent graduate of the MSc in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management at Oxford University and is currently a Junior Environmental Consultant for CH2M HILL.

Meredith Root-Bernstein

researches conservation in productive anthropogenic mediterranean-climate socio-ecological systems. She is currently a member of the interdisciplinary Anthropocene project team at Aarhus University, Denmark.

References

- Alagona PA. Biography of a “feathered pig”: The California condor conservation controversy. Journal of the History of Biology. 2004;37:557–583. doi: 10.1007/s10739-004-2083-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armesto JJ, Manuschevich D, Mora A, Smith-Ramirez C, Rozzi R, Abarzúa AM, Marquet PA. From the Holocene to the Anthropocene: A historical framework for land cover change in southwestern South America in the past 15000 years. Land Use Policy. 2010;27:148–160. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Ovalle C, Avendano J. Ecological and economic rehabilitation of degraded ‘Espinales’ in the subhumid Mediterranean-climate region of central Chile. Landscape Urban Planning. 1993;24:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0169-2046(93)90077-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aveling R, Mitchell A. Is rehabilitating Orang Utans worth while? Oryx. 1982;16:263–271. doi: 10.1017/S0030605300017506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bardsley D, Edwards-Jones G. Stakeholders’ perceptions of the impacts of invasive exotic plant species in the Mediterranean region. GeoJournal. 2006;65:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s10708-005-2755-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barua M, Root-Bernstein M, Ladle RJ, Jepson P. Defining flagship uses is critical for flagship selection: A critique of the IUCN climate change flagship fleet. AMBIO. 2011;40:431–435. doi: 10.1007/s13280-010-0116-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla M, Gustin M, Celada C. Species appeal predicts conservation status. Biological Conservation. 2013;160:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton SD. Environment and identity. In: Clayton SD, editor. The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 164–180. [Google Scholar]

- Crites SL, Jr, Fabrigar LR, Petty RE. Measuring the affective and cognitive properties of attitudes: Conceptual and methological issues. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:619–694. doi: 10.1177/0146167294206001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Val GDLF, Mezquida JA, de Lucio Fernández JV. El aprecio por el paisaje y su utilidad en la conservación de los paisajes de Chile central. Rev Ecosistemas. 2004;13:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K. The interplay of affect and cognition in attitude formation and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:202–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.2.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin WL, Bas F, Bonacic C, Cunazza C, Soto N. Striving to manage Patagonia guanacos for sustained use in the grazing agroecosystems of southern Chile. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 1997;25:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes ER, Espinosa GA, Fuenzalida I. Cambios vegetacionales recientes y percepción ambiental: el caso de Santiago de Chile. Revista de geografía Norte Grande (Chile) 1984;11:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido Escobar, F. 2010. La importancia de los camélidos en el mundo indígena y prehispánico nacional. In Plan Nacional de Conservación del Guanaco (Lama guanicoe) en Chile 2010–2015: Macrozona Norte y Centro, ed. M.P. Grimberg and M.P. Pardo, 25–29. Santiago: CONAF.

- Gifford R, Sussman R. Environmental Attitudes. In: Clayton SD, editor. The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gobster PH. Yellowstone hotspot: Reflections on scenic beauty, ecology and the aesthetic experience of landscape. Landscape Journal. 2008;27:2–8. doi: 10.3368/lj.27.2.291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimberg Pardo, M.P. 2010. Plan Nacional de Conservación del Guanaco (Lama guanicoe) en Chile 2010–2015, Macrozona Norte y Centro. Chile: CONAF.

- Hull, R.B., and W.P. Stewart. 1992. Validity of photo-based scenic beauty judgments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 12: 101–114.

- Irarrázabal, A.R. 2008. El orgullo de preservar nuestra identidad, Tema Empresa. Tell Magazine. http://assets.wanaku.cl/prensa/20080309_prensa_entrevista_tell.pdf. Accessed June 2013.

- Iriarte A. Normativa legal sobre conservación y uso sustentable de vicuña y guanaco en Chile. In: González B, Bas F, Tala C, Iriarte A, editors. Manejo Sustentable de la Vicuña y el Guanaco. Santiago: SAG, PUC, FIA; 2000. pp. 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jepson P, Canney S. Values led conservation. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2003;12:271–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-822X.2003.00019.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kempton W, Boster JS, Hartley JA. Environmental values in American Culture. Cambridge: MIT; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kueffer, C., and C.N. Kaiser-Bunbury. 2013. Reconciling conflicting perspectives for conservation in the Anthropocene. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment. doi:10.1890/120201.

- Ladle, R., and P. Jepson. 2008. Towards a biocultural theory of avoided extinction. Conservation Letters 1: 111–118.

- Leader-Williams N, Dublin H. Charismatic megafauna as ‘flagship species’. In: Entwistle A, Dunstone N, editors. Priorities for the Conservation of Mammalian Diversity: Has the Panda had its day? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 53–81. [Google Scholar]

- MEA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment) Ecosystems and human well-being. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. 1980. Human influence on the distribution and abundance of wild Chilean mammals: Prehistoric—Present. PhD thesis, University of Washington.

- Montag J, Patterson ME, Freimund WA. The wolf viewing experience in the Lamar Valley of Yellowstone National Park. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 2005;10:273–284. doi: 10.1080/10871200500292843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montes MC, Carmanchahi PD, Rey A, Funes MC. Live shearing free-ranging guanacos (Lama guanicoe) in Patagonia for sustainable use. Journal of Arid Environments. 2006;64:616–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 2000;403:853–859. doi: 10.1038/35002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novaro ASJ. Restoration of the Guanaco, Icon of Patagonia. In: Fearn E, Redford KH, Woods W, editors. State of the wild: A global portrait. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2010. pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro LM, Pereira HM. Rewilding abandoned landscapes in Europe. Ecosystems. 2012;15:900–912. doi: 10.1007/s10021-012-9558-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papworth SK, Rist J, Coad L, Milner-Gulland EJ. Evidence for shifting baseline syndrome in conservation. Conservation Letters. 2009;2:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons DR. “Green fire” returns to the Southwest: Reintroduction of the Mexican Wolf. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 1998;26:799–807. [Google Scholar]

- Pauchard A, Villarroel P. Protected areas in Chile: History current status and challenges. Natural Areas Journal. 2002;22:318–330. [Google Scholar]

- Redford KH, Berger J, Zack S. Abundance as a conservation value. Oryx. 2013;47:157–158. doi: 10.1017/S0030605313000331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rolston H., III . Beauty and the Beast: Aesthetic Experience of wildlife. In: Decker DJ, Goff GR, editors. Valuing wildlife: Economic and social perspectives. London: Westview Press; 1987. pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Root-Bernstein, M. 2014. Nostalgia, the fleeting and the rare in Chilean relationships to nature and non human animals. Society and Animals 22: 560–579 (online first).

- Root-Bernstein M, Armesto J. Selection and implementation of a flagship fleet in a locally undervalued region of high endemicity. AMBIO. 2013;42:776–787. doi: 10.1007/s13280-013-0385-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root-Bernstein M, Jaksic F. The Chilean Espinal: Restoration for a Sustainable Silvopastoral System. Restoration Ecology. 2013;21:409–414. doi: 10.1111/rec.12019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders FP. Seeing and doing conservation differently: A discussion of landscape aesthetics, wilderness, and biodiversity conservation. Journal of Environment Development. 2013;22:3–24. doi: 10.1177/1070496512459960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon PJ, van Heezik H. Reintroductions to “Ratchet Up” public perceptions in Biodiversity. In: Bekoff M, editor. Ignoring nature no more. London: The University of Chicago Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti JA. Diversity and conservation of terrestrial vertebrates in mediterranean Chile. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. 1999;72:493–500. [Google Scholar]

- Skewes O, González F, Maldonado M, Ovalle C, Rubilar L. Desarrollo y evaluación de técnicas de cosecha y captura de guanacos para su aprovechamiento comercial y sustentable en Tierra del Fuego. In: González B, Bas F, Tala C, Iriarte A, editors. Manejo Sustentable de la Vicuña y el Guanaco. Santiago: SAG PUC FIA; 2000. pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Soulé ME. What is conservation biology? BioScience. 1985;35:727–734. doi: 10.2307/1310054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Surova D, Pinto-Correia T. Landscape preferences in the cork oak Montado region of Alentejo southern Portugal: Searching for valuable landscape characteristics for different user groups. Landscape Research. 2008;33:311–330. doi: 10.1080/01426390802045962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teel TL, Manfredo MJ, Stinchfield HM. The need and theoretical basis for exploring wildlife value orientations cross-culturally. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 2007;12:297–305. doi: 10.1080/10871200701555857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo D, Agudelo MS, Bentley AL. Shifting of ecological restoration benchmarks and their social impacts: Digging deeper into Pleistocene re-wilding. Restoration Ecology. 2011;19:564–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2011.00798.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211:453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Berg H, Manstead ASR, van der Pligt J, Wigboldus DHJ. The impact of affective and cognitive focus on attitude formation. The Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;42:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veríssimo D. Influencing human behaviour: an underutilized tool for biodiversity management. Conservation Evidence. 2013;10:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Veríssimo, D., I. Fraser, J. Groombridge, R. Bristol, and D.C. MacMillan. 2009. Birds as tourism flagship species: A case study of tropical islands. Animal Conservation 12: 549–558.