Abstract

Predicting who may leave a fishery is an important consideration when designing capacity reduction programs to enhance both ecological and economic sustainability. In this paper, the relationship between satisfaction and the desire to exit a fishery is examined for the Queensland East Coast Trawl fishery. Income from fishing, and changes in income over the last 5 years, were key factors affecting overall satisfaction. Relative income per se was not a significant factor, counter to most satisfaction studies. Continuing a family tradition of fishing and, for one group, pride in being a fisher was found to be significant. Satisfaction with fishing overall and the challenge of fishing were found to be the primary drivers of the desire to stay or leave the fishery. Surprisingly, public perceptions of fishing, trust in management and perceptions of equity in resource allocation did not significantly affect overall satisfaction or the desire to exit the fishery.

Keywords: Fishing, Satisfaction, Exit behavior, Capacity reduction

Introduction

Overcapacity in fisheries is widely accepted as a major issue globally, affecting both resource sustainability as well as economic and social outcomes from fishing (Beddington et al. 2007). Issues such as non-malleability of capital (Clark et al. 1979) make it easier for capacity to increase in a fishery in response to short-term improvement in economic performance than to exit. While some management systems, such as individual transferable quotas, facilitate autonomous adjustment (Grafton and McIlgorm 2009), such systems are not feasible or acceptable for all fisheries, and the manner in which they are implemented (e.g., total allowable catch setting) can also influence their effectiveness. Hence, other approaches may be necessary to help reduce overcapacity and hence total fishing effort. Foremost of these is the buyback program, in which vessels and/or licenses are bought out, usually by government with or without some contribution by industry. Such systems may offer only a short-term relief from overcapacity as they do not reduce the major underlying causes of overcapacity, namely lack of individual property rights in the fishery (Holland et al. 1999). Anticipation of future buyback programs may even increase levels of overcapacity in the future (Clark et al. 2005), as these create expectations of higher future profits as well as providing a market for surplus capital that otherwise would not exist (effectively reducing the risk of investment). Despite these issues, buybacks remain a common approach to effort reduction in fisheries worldwide, and are often implemented as a means of reducing effort while transitioning to other management arrangements.

The effectiveness of effort reduction schemes is determined not only by how many vessels exit a fishery, but also which vessels. Heterogeneity in vessel capacity utilisation and/or technical efficiency can have a substantial impact on the effectiveness of any buyback scheme (Pascoe and Coglan 2000). In recent years, there have been numerous attempts to estimate which factors will affect the choice of fishers to exit a fishery, although these have often been based on vessel movements out of the fishery rather than fishers per se (Quillérou and Guyader 2012). These have largely focused on economic drivers, namely prices, catch rates (which affect revenue) and costs (Ward and Sutinen 1994; Pradhan and Leung 2004; Tidd et al. 2011), although the level of capacity utilisation was also found to be a reasonable predictor of which vessels are most likely to exit a fishery (Pascoe et al. 2013b). These approaches largely assume that fishers stay in the fishery if they gain sufficient utility by doing so, or exit if they do not, where utility is largely defined in terms of profitability or income. Studies of leavers suggest that they believe they are better off financially than if they had stayed in the fishery (e.g., Campbell et al. 2000), supporting this assumption.

Recent developments in the area of the economics of happiness suggest that subjective measures of happiness or satisfaction provide a better indicator of the level of utility than economic measures such as income alone (Tella and MacCulloch 2006). While income adds to life satisfaction up to a certain point, beyond that point additional income does very little (Cummins 2000). Others have found that individual satisfaction is generally found to be correlated with relative income (Tella and MacCulloch 2006; Clark et al. 2008; Boyce et al. 2010), meaning the level of income relative to others or how that income has changed relative to others. However, overall happiness or satisfaction is affected by a wide range of factors other than income, including an individual’s personal circumstances (including their health, relationships, and ability to achieve desired outcomes from life, factors often correlated with demographic characteristics such as marital status, age, education and household characteristics), and the broader societal circumstances they live in (such as whether they live in a safe community, have positive social capital, and a just and fair government, to name a few) (Peiró 2006; Vemuri and Costanza 2006; Welsch 2009; Frey and Stutzer 2010; Diener et al. 2013).

Relatively few studies have attempted to link these social drivers of utility to fisher behavior such as exiting. Muallil et al. (2011) found that heterogeneity in fishers’ willingness to exit a fishery was linked to social drivers such as age, education, dependency on the fishery for their livelihood and their individual adaptive capacity. Several previous studies of fisher job satisfaction have suggested that, for many, fishing is more than a livelihood and instead is viewed as a ‘way of life’, and further that even when facing decreased catches and lower incomes, many fishers are not likely to choose to leave the industry (Gatewood and McCay 1988; Coulthard 2012; Monnereau and Pollnac 2012; Pollnac et al. 2012). Related to this, some argue that fishers have a strong attachment to their occupation and are unlikely and/or unwilling to look for an alternative profession (Bavinck et al. 2012; Cinner 2014). Others, however, have found a direct link between a declining status of commercial fishing and a corresponding decline in fisher’s reported well-being (Smith and Clay 2010), such that at some point a desire to leave may develop.

Marshall and Marshall (2007) suggest that there are wide variances in individual fisher resilience and adaptive capacity based on their confidence in their skills and ability, their coping ability and their ability to assess risks. However, these may lead to either exiting or remaining in a fishery depending on their level of interest in remaining and their ability to access other options. Consequently, satisfaction with the industry and barriers to exit are likely dominant factors affecting exiting behavior.

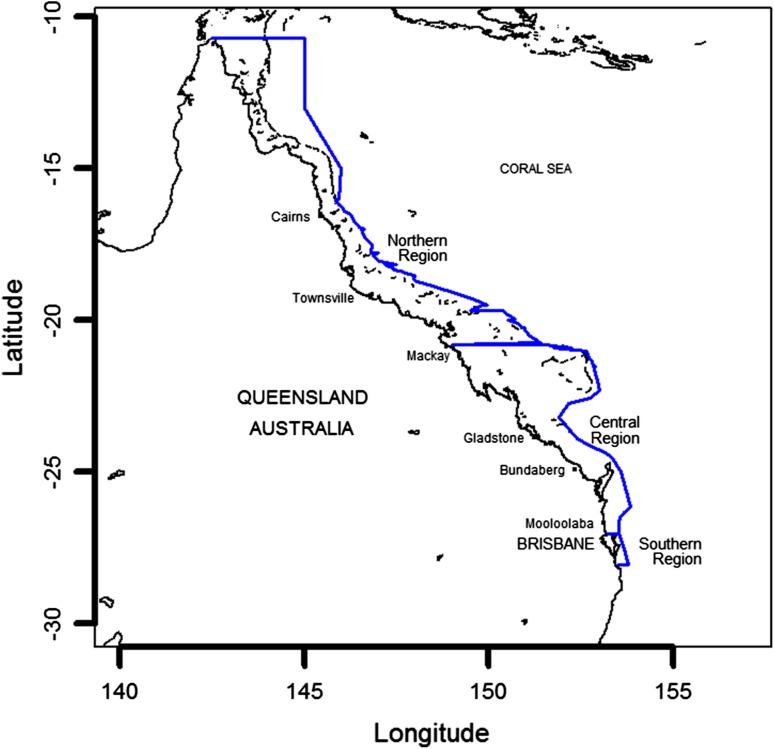

In this study, we examine the role of fisher satisfaction on their desire to exit the fishery, and also examine what factors affect their level of satisfaction. A better understanding of which fishers are most likely or willing to exit a fishery will provide better information on the likely effectiveness of different capacity management systems, and also guide which incentives need to be adjusted to achieve desired capacity targets. As a case study, we examine fishers’ stated satisfaction and desire to exit the Queensland East Coast Trawl fishery (Fig. 1). The Queensland East Coast Trawl fishery is a multi-species fishery that primarily targets several prawn species, Moreton Bay bugs and scallops. The trawl fishery is Queensland’s largest commercial fishery, catching product valued at approximately $86 million in 2012 (DAFF 2013), representing almost half the total value of all catch in the State (Skirtun et al. 2012). The fishery has about 450 licensed vessels, with many of these operating at less than full capacity as a result of declining profitability due to declining prawn prices and increasing fuel costs. The increase in prawn aquaculture globally has had a substantial downward impact on all prawn prices, and continuing growth of this sector is expected to produce further price declines.

Fig. 1.

The area of the Queensland East Coast Trawl fishery and fishing regions

The fishery is managed through individual transferable effort units, which in principle provide an opportunity for autonomous adjustment by providing a mechanism for fishers to exit the fishery. However, the falling prawn prices and increasing fuel costs have resulted in a substantial surplus of units on the market, with the total allowable effort not declining in line with the new economic conditions. In 2012, only 1.5 million effort units were used out of a total available pool of 2.95 million (DAFF 2013). The substantial latent effort in the fishery is of considerable concern to both managers and industry, the former in terms of their lack of ability to effectively control fishing effort in different sectors of the fishery (if required) and the latter in terms of the loss of asset values. With over 40 % of the effort units being unutilised, unit trading values and the quantity traded have fallen to negligible levels (Dichmont et al. 2013). As a consequence, the ability of the remaining fishers to exit the fishery without substantial loss is limited. Industry has proposed that a buyback be implemented to address this problem.

Materials and methods

A survey of the fishery was undertaken during 2012, primarily to collect data relevant for an assessment of the social performance of the fishery. A copy of the survey instrument is provided in Triantafillos et al. (2014). In total, 60 fishers were interviewed face-to-face along the Queensland east coast, representing roughly 20 % of the active vessels. The sample consisted of 48 owner operators, nine employed skippers, and three company fleet managers responsible for several vessels each.

There are three main regions in the fishery. The northern region is dominated by larger vessels mostly fishing in both inshore and offshore for tiger and endeavor prawns. The central region consists of both smaller vessels fishing mostly inshore and larger vessels fishing offshore for tiger, endeavor, red spot and blue leg king prawns, Moreton Bay bugs and scallops. The southern region consists of mostly inshore vessels fishing primarily for eastern king prawns, scallops and Moreton Bay bugs. The survey collected information from 18 fishers in the northern region of the fishery, 22 from the central part and 20 from the southern region.

The surveys were conducted on an opportunistic basis. Most of the northern interviews were undertaken while fishers were offloading and/or refuelling. In the other two regions, the fishers were approached and interviewed during a series of meetings organised by the management agency to discuss future management options in the fishery. Hence, the sample is potentially biased as it is limited to only those fishers who attended these meetings, or those northern boats operating during the time of the survey. On average, around one half of the fishers at each meeting participated in the survey. Reasons for non-participation or non-attendance at the meetings were not explored. Unfortunately, fisher information other than contact details is not collected by management agencies so the representativeness of the sample cannot be assessed. However, the spatial distribution of the sample was proportional to the known distribution of fishers, so spatial biases at least are likely to be small.

Information was collected on a number of social metrics including a subjective measure of satisfaction with fishing overall, as well as subjective measures of satisfaction with individual aspects of fishing, such as income earned, being part of the industry (i.e., being a fisher), following on family traditions, and the challenge associated with fishing. Satisfaction with the existing infrastructure supporting the fishery was also questioned. In our study, satisfaction was elicited using a 10 point scale with 10 being fully satisfied and 1 being completely unsatisfied. The results were converted to an index from 0.1 to 1.

Information was also collected to develop a relative income from fishing measure (relative to the average income), as well as how income had changed over the last one and 5 years.1 The subjective importance of fishing to fishers, and their views as to the degree to which fishing was a lifestyle or business oriented activity to them was also collected. Similarly, their perception as to how fishing was viewed by the general community was elicited, along with their perceptions as to their confidence in fisheries management and how they were treated relative to other users of the marine resources.

Finally, their desire to either stay in the fishery or leave was collected. To separate out the effects of exiting due to a wish to retire as compared to dissatisfaction with the fishery, we asked specifically if they aimed to exit before retirement or at retirement. There is no compulsory retirement age in Australia, so the decision to retire depends on personal financial and family situations rather than age. Family situations may include, for example, having someone to pass the business on to—part of maintaining family traditions.

The relative roles of factors influencing satisfaction with fishing were estimated using tobit analysis. Tobit analysis was applied as the measure of satisfaction is truncated at 0.1 at the lower end and 1 at the upper end. The desire to stay or exit the fishery was a binary variable with a value of 1 if the fisher wished to leave and 0 otherwise. The factors affecting this decision were examined using logit analysis, from which the probability of wishing to leave could be estimated.

Results

Fisher satisfaction

The median level of satisfaction with fishing was 0.6, with the full range being observed in the data (Fig. 2). The distributions were similar for the different roles the interviewees played in the fishery (i.e., fleet manager, owner operator, or employed skipper), while the median score for fishers operating mostly in the north was slightly lower than the central or southern parts of the fishery, although not significantly so.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of fisher satisfaction by a role and b region of the fishery

Employed skippers tended to view fishing more as a business, while a higher proportion of owner operators tended to view the fishery as a more balanced combination of lifestyle and business (Fig. 3a). However, there was substantial variability in these values within each group, and the two groups were not significantly different in this regard. Similarly, fishers operating out of southern ports tended to have a higher lifestyle component to their attitude to fishing (Fig. 3b). In contrast, owner operators tended to place greater importance on fishing than many employed skippers (Fig. 3c), and this was fairly consistent across regions (Fig. 3d). These results suggest owner operators tend to have a greater attachment to fishing than employed skippers, and based on other studies (e.g., Cinner 2014), may be less willing to exit the fishery. Given their level of investment in the fishery (compared to employed skippers with no investment), such an attachment is not unexpected.

Fig. 3.

Key socio-economic indicators: attitude to business by a ownership and b region; importance of fishing by c ownership and d region; relative income by e ownership and f region; change in income over the last year (g) and last 5 years (h)

Median incomes derived from fishing were generally just below the average income for the Australian population as a whole (Fig. 3e, where 1 = average income), although a wide range of incomes was observed. Incomes in the central region of the fishery tended to be slightly higher than those in the north or south (Fig. 3f). Changes in income over 1 and 5 years were measured in a relative scale, with zero indicating no real change, 1/−1 indicated some change and 2/−2 indicating a large change. Most fishers indicated no change or some negative change across all regions over the last year (Fig. 3g), but many in the central and southern region experienced more substantial negative change over the last 5 years (Fig. 3h). In contrast, incomes of many in the northern region increased over the last 5 years.

The relationship between these factors with the level of satisfaction was estimated using tobit analysis. Initially, all potentially relevant variables were included in the model (Table 1), and the analysis was initially limited to fishers who provided information for all variables.2 Non-significant variables were removed in a stepwise manner, with the least individually significant variable removed and the model reassessed based on the AIC score.

Table 1.

Tobit regression results for factors affecting satisfaction with fishing

| Unrestricted model | Restricted model | Restricted model, additional observations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Significance (%) | Estimate | SE | Significance (%) | Estimate | SE | Significance (%) | |

| Intercept | 0.511 | 0.159 | 0 | 0.416 | 0.040 | 0 | 0.460 | 0.035 | 0 |

| Fishing income | −0.073 | 0.090 | 42 | ||||||

| Income 1 year | −0.024 | 0.049 | 63 | ||||||

| Income 5 years | 0.035 | 0.032 | 27 | 0.070 | 0.028 | 1 | |||

| Satisfaction with | |||||||||

| Money | 0.047 | 0.026 | 7 | 0.043 | 0.026 | 10 | |||

| Maintaining family tradition | 0.093 | 0.038 | 1 | 0.094 | 0.032 | 0 | 0.154 | 0.025 | 0 |

| Being part of the industry | 0.107 | 0.036 | 0 | 0.088 | 0.033 | 1 | |||

| The challenge of fishing | 0.043 | 0.035 | 22 | ||||||

| Infrastructure | −0.032 | 0.037 | 37 | ||||||

| Perceptions of the community | 0.028 | 0.153 | 85 | ||||||

| Importance of fishing to you | 0.023 | 0.098 | 81 | ||||||

| Attitude (1 = lifestyle) | 0.036 | 0.037 | 33 | ||||||

| South | −0.076 | 0.108 | 48 | ||||||

| North | −0.079 | 0.100 | 43 | ||||||

| Skipper | −0.021 | 0.096 | 82 | ||||||

| Log(scale) | −1.640 | 0.129 | 0 | −1.556 | 0.129 | 0 | −1.469 | 0.112 | 0 |

| AIC | 33.209 | 17.385 | 28.753 | ||||||

| Log-likelihood | −0.605 | −3.693 | −10.38 | ||||||

| Wald-statistic | 61.45 | 50.27 | 54.65 | ||||||

| Number of observations | 42 | 42 | 57 | ||||||

| Right censored (=1) | 4 | 4 | 7 | ||||||

| Left censored (=0.1) | 5 | 5 | 6 | ||||||

| Uncensored | 33 | 33 | 44 | ||||||

Fishing income and satisfaction with infrastructure were removed relatively early in the stepwise process as they were found to be not significant in the regression models. These variables also had the greatest non-response, so their removal had an additional advantage of increasing the sample available for estimation. The model was also re-estimated without these variables and an expanded sample, again using a stepwise process to determine the most appropriate restricted model.

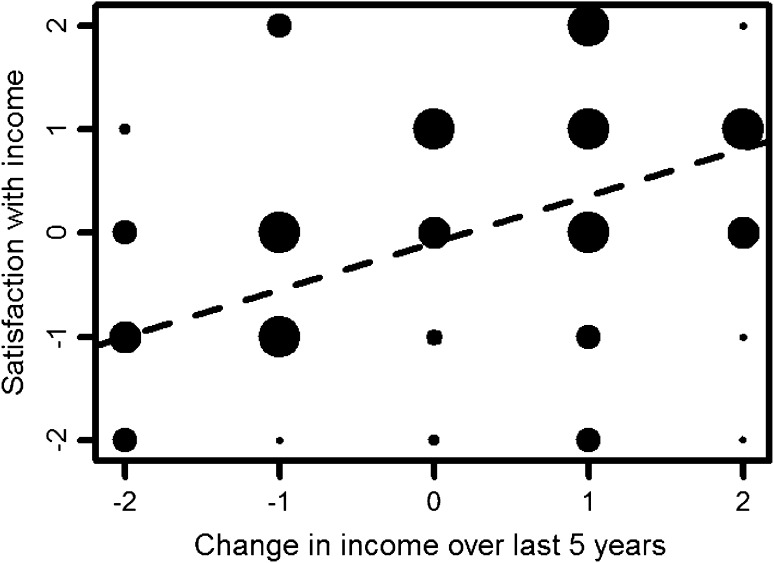

The results of the model (Table 1) suggest that, based on the sample with complete responses, the key drivers of overall satisfaction with fishing depend on the fisher’s satisfaction with their level of income, continuing a family tradition and being part of the industry (i.e., being a fisher). These latter factors are generally linked to attachment to occupation, so their significance is consistent with experiences elsewhere (Cinner 2014). Their actual income relative to the average income was not a key component of overall satisfaction—some were satisfied with relatively low levels of income while others were dissatisfied with above average earnings. With the larger sample (i.e., including those that did not respond to the income and infrastructure questions), satisfaction with income became non-significant and change in income over the last 5 years became significant (Table 1). While income change and satisfaction with income were only weakly correlated (r = 0.28), the median satisfaction increased with income change (Fig. 4), suggesting that income change affects overall satisfaction with fishing, and hence the two variants of the model are broadly consistent. Carrying on a family tradition was again also a factor affecting overall satisfaction with fishing with the expanded sample, although being part of the industry was not a significant factor.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between satisfaction with income and income change over the last 5 years. A value of 0 indicates no change in income (x-axis), and neither satisfied or dissatisfied with income (y-axis). The size of the circles is proportional to the number of responses in each category

Desire to leave the fishery

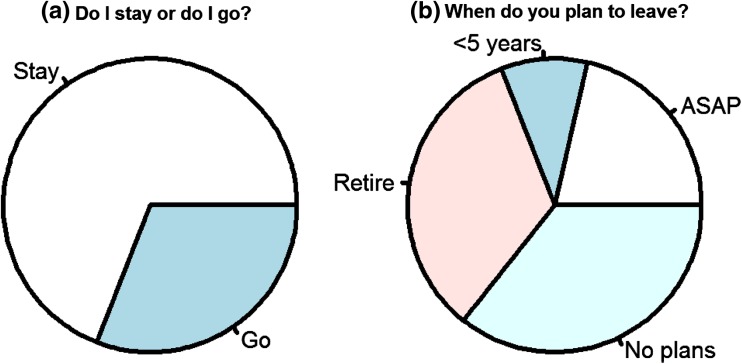

The role of satisfaction and other social drivers on the desire to stay or leave the fishery was explored using logit analysis. The logit model used a binary dependent variable with 1 representing a desire to leave within the next 5 years (including as soon as possible) and 0 representing an intention of staying at least until retirement (or beyond).

The relative frequency of the binary and more disaggregated choices are illustrated in Fig. 5. Only around 25 % of fishers expressed a desire to leave, similar to studies in other fisheries in the area (Tobin et al. 2010), with most of these wishing to leave as soon as possible. In contrast, a greater proportion of fishers had no plans of leaving and expected to remain in the fishery beyond retirement age.

Fig. 5.

Desire to exit or stay in the fishery

The logit model initially included satisfaction and those variables that were not significant components of satisfaction. Again, relative fisher income and satisfaction with infrastructure were both non-significant in the initial estimates, so were removed allowing an expanded sample to be included in the analysis. As with the satisfaction model, non-significant variables were removed in a stepwise process with the restricted model assessed at each stage based on the AIC.

The level of satisfaction with fishing was found to be a key explanatory variable in the model (Table 2), with satisfaction with the challenge of fishing also being significant at the model level (i.e., excluding it was found to significantly weaken the model even though the coefficient itself was not significant), but only significant at the 10 % level individually. As the dependent variable is the desire to exit the fishery, the negative signs on the coefficients suggest that the probability of wanting to leave increases as the level of overall satisfaction and the challenge of fishing decreases.

Table 2.

Logit regression on determinants of desire to exit the fishery

| Unrestricted model | Restricted model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Significance (%) | Estimate | SE | Significance (%) | |

| Intercept | 2.738 | 1.989 | 17 | 0.748 | 0.770 | 33 |

| Satisfaction with fishing | −4.876 | 2.318 | 4 | −3.710 | 1.676 | 3 |

| Importance of fishing to you | −1.533 | 1.791 | 39 | |||

| Skipper | −0.457 | 1.339 | 73 | |||

| Satisfaction with | ||||||

| Being part of the industry | 0.415 | 0.515 | 42 | |||

| The challenge of fishing | −0.696 | 0.450 | 12 | −0.523 | 0.307 | 9 |

| Perceptions of the community | 0.316 | 0.432 | 46 | |||

| Perceptions of management | ||||||

| Managers doing a good job | −0.234 | 0.583 | 69 | |||

| Trust managers | 0.129 | 0.583 | 73 | |||

| Perceptions of treatment (fairness) | ||||||

| Access to areas | −0.095 | 0.543 | 87 | |||

| Permitted species | 0.139 | 0.497 | 78 | |||

| AIC | 65.429 | 51.556 | ||||

| % Correct stay | 84 % | 83 % | ||||

| % Correct leave | 64 % | 60 % | ||||

The model performs reasonably well in terms of predicting who is likely to wish to stay in the fishery or leave. The logit model estimates the probability of wanting to leave based on the coefficients and variable values. Assuming a probability of greater than 0.5 indicates a desire to leave, then the model was able to correctly identify those desiring to leave 60 % of the time. The model performed better in terms of those wishing to stay, predicting over 80 % correctly.

Discussion and conclusions

Measures of happiness or satisfaction are often suggested as alternative measures of performance to traditional economic measures of profitability. The assumption underlying this is that utility is broader than just monetary earnings, and that satisfaction captures the effects of these other utility-generating features of their activities. In our study, we find that the level of income relative to others in the economy is not a key driver of satisfaction, but changes in income over time affects the satisfaction with income, and also overall satisfaction with fishing. This is in contrast to studies or other industries or groups (e.g., Tella and MacCulloch 2006; Clark et al. 2008) which suggest that change in incomes is less important than relative income. In most occupations, incomes tend to move in a positive direction (at least in nominal terms). In fishing, catches fluctuate as a result of natural stock abundance changes, management controls, weather conditions and, to some degree, luck (as fishers are chasing an unseen fugitive resource). External factors such as the strength of the exchange rate have an impact on the price received for the catch. Fishing costs are also driven by a range of factors, with input prices being a key factor affecting income. Consequently, incomes may fluctuate substantially year to year, but longer term persistent changes may have an impact on satisfaction.

Non-monetary factors also affect the level of satisfaction. Other studies suggest that marital status, age, and length of time fishing are significant determinants of satisfaction and willingness to stay in the fishery (Polinac and Poggie 2008; Muallil et al. 2011; Pollnac et al. 2012). Unfortunately, these variables were not collected in the survey, although these variables are often associated with general happiness (Peiró 2006), which may or may not also affect general attitudes toward work (Ashkanasy 2011). Hence, they may affect fishers’ attitudes to fishing but may not be directly related to their level of satisfaction with fishing. However, the level of satisfaction with continuing a family tradition of fishing was a significant factor affecting satisfaction, while satisfaction with being part of the industry (effectively pride of being a fisher) was also found to be significant with a sub-set of the data.

The level of satisfaction has a significant bearing on the fishers’ desire to either stay in the fishery or leave. Studies elsewhere have also noted a relationship between satisfaction with fishing and the likelihood of leaving the industry (Pollnac et al. 2012), although these studies are limited. Tobin et al. (2010) suggest that a low level of satisfaction may mean fishers are more likely to want to leave, but may not be able to if they believe they do not have options outside of fishing. Hence desire and ability to actually leave may be separate outcomes. Our results and those of others strongly support that the decisions fishers make are not driven solely by economic considerations, but rather are driven by a mix of factors that may include their level of attachment to fishing, family considerations and lifestyle considerations, among others. While well recognised in fields that examine how best to support successful adaptation of fishers to change (e.g., Marshall and Marshall 2007), this understanding of fisher motivations is rarely applied to understanding the decision to exit fishing—even though this decision may be a positive adaptive response to change in the industry.

While not a factor affecting overall satisfaction, the challenge of fishing is also a significant determinant of the desire to leave the fishery. Pollnac et al. (2012) suggested that self actualisation is a key factor affecting a fisher’s willingness to stay in the fishery, and that this is separate from satisfaction with fishing. Fishers who find the industry less challenging are also less likely to fulfill self actualisation. The relatively risky nature of fishing as an occupation attracts and retains individuals with an active, adventurous, aggressive, and courageous personality (Polinac and Poggie 2008), potentially explaining why fishers remain in a fishery when economic rationality would suggest they should leave (Pollnac et al. 2012).

The lack of significance of the other variables is potentially of more interest than the two key variables that were significant, as the latter could have been expected a priori. Fishers are often vocal about their distrust of management, their unfair treatment in terms of allocation to the resource (such as areas or species that they are permitted to catch) and their perceived poor standing in society (Hernes et al. 2005; Dwyer et al. 2008). Commercial fishing in Australia is generally viewed pessimistically, with the media often focusing on negative environmental issues, by-catch, discarding, and illegal fishing (Aslin and Byron 2003). However, community perceptions—although generally believed to be negative—were not significant determinants of either satisfaction with fishing or the desire to exit the industry. Similarly, perceptions of equitable resource allocation and fishers’ trust in management were also not significant in determining satisfaction or desire to leave. This result is perhaps less surprising, as studies of management objective importance in the fishery have found that improving equity has a relatively low importance to fishers compared to improving economic performance (Pascoe et al. 2013a).

Previous studies of exit behavior in fisheries have largely relied on information collected through routine monitoring of the fishery (e.g., logbook data) and also were able to provide reasonable indicators of which vessels are likely to exit the fishery (e.g., Tidd et al. 2011; Pascoe et al. 2013b). While satisfaction with fishing is a significant factor identifying which fishers are most likely to want to exit the fishery, measuring satisfaction requires additional information to be collected. Such a measure could, potentially, also be captured routinely as part of the ongoing monitoring of the fishery. This is particularly useful if some form of capacity reduction program is being developed. Understanding the distribution of satisfaction in the fishery may provide managers with a better ability to predict who may take up an exit package, and whether those likely to are the ones who most meet the targets of the exit program.

The analysis focuses on the desire to exit the fishery, rather than their ability to exit the fishery. For many owner-operators, their capital investment in the industry is substantial, and difficulty in finding buyers or alternative uses of the vessel is a substantial barrier to exit (Clark et al. 1979; Dichmont et al. 2013). In addition, there are a substantial number of excess effort units in the fishery, reducing the value of the business assets to below which the operators feel they are valued (Dichmont et al. 2013). While the lower license values reduce the opportunity cost of exiting, there is also a loss of perceived value from selling licenses at a lower price. Staying in the fishery also has an option value, as future management changes may improve both profitability and also license values.

In Australia and elsewhere, there is increasing interest in assessing the social performance of fisheries management to complement economic and environmental sustainability assessments as part of the ecosystem based approach to fisheries management and the broader principles of ecological sustainable development (Fletcher et al. 2005). Satisfaction measures are a key component of such social assessments, and hence data are likely to become increasingly available.

While economic influence is important, a more global examination of the factors driving fisher behavior and decisions is needed in order to effectively target exit packages (van Putten et al. 2012). The use of measures of satisfaction with fishing can contribute to this; future work should consider identifying more specific domains of satisfaction with fishing, that can support improved understanding of how management changes affect fisher satisfaction, and when this is likely to be associated with a decision to exit the fishery.

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken as part of the FRDC funded project “Developing and Testing Social Objectives and Indicators for Fisheries Management (FRDC Project 2010/040)”, with support from the CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere Flagship. We would also like to thank the fishers who took part in the survey, the owners of the mothership that assisted us with the surveys in the northern region, and the two anonymous reviewers who provided valuable feedback on the earlier draft of the manuscript.

Biographies

Dr. Sean Pascoe

is a marine resource economist in the CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere Flagship. Before joining CSIRO in 2006, he was a Professor of Natural Resource Economics at the University of Portsmouth, UK, and is currently an adjunct Professor of Economics at the Queensland University of Technology. His research interests include modeling fisher behavior, and the interface between fisheries management and biodiversity conservation.

Toni Cannard

is a socio-economist in the CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere Flagship. She is currently working on several multidisciplinary fisheries and coastal ecosystem based projects, as well as undertaking her PhD on triple bottom line coastal management in Australia at the University of Wollongong.

Eddie Jebreen

is a fisheries manager in the Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. He is primarily responsible for the management of the Queensland trawl and Torres Strait fisheries.

Dr. Catherine M. Dichmont

is a senior principal research scientist with the CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere Flagship. Her main research areas involve stock assessment, modeling natural systems, natural resource management, shared fisheries stocks, and management strategy evaluation (MSE).

Dr. Jacki Schirmer

is a social scientist at the University of Canberra. Her research focuses on understanding how people’s access to and use of natural resources affects their health and wellbeing, and how changes in management of natural resources such as forests, fisheries, and rural land affect the wellbeing of workers and rural communities.

Footnotes

For owner-operators, income largely reflects their cash profits. Essentially, it is the money left over once all the costs have been paid. While potentially vague, discussions with industry in earlier studies suggested that this was the most appropriate measure of income from the fishers’ perspective (e.g., Courtney et al. 2012, 2014; Dichmont et al. 2013). For employed skippers, income represents their share of revenue (Courtney et al. 2014).

The fleet managers were excluded from the analysis as they would have very different experiences to owner operators or employed skippers in the fishery due to their different role.

Contributor Information

Sean Pascoe, Phone: 71 7 3833 5966, Email: sean.pascoe@csiro.au.

Toni Cannard, Email: toni.cannard@csiro.au.

Eddie Jebreen, Email: eddie.jebreen@daff.qld.gov.au.

Catherine M. Dichmont, Email: cathy.dichmont@csiro.au

Jacki Schirmer, Email: jacki.schirmer@canberra.edu.au.

References

- Ashkanasy NM. International happiness: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Perspectives. 2011;25:23–29. doi: 10.5465/AMP.2011.59198446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aslin HJ, Byron IG. Community perceptions of fishing: Implications for industry image, marketing and sustainability. Canberra: Fisheries Research and Development Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bavinck M, Pollnac R, Monnereau I, Failler P. Introduction to the special issue on job satisfaction in fisheries in the global south. Social Indicators Research. 2012;109:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beddington JR, Agnew DJ, Clark CW. Current problems in the management of marine fisheries. Science. 2007;316:1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1137362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce CJ, Brown GDA, Moore SC. Money and happiness: Rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychological Science. 2010;21:471–475. doi: 10.1177/0956797610362671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, Brown D, Battaglene T. Individual transferable catch quotas: Australian experience in the southern bluefin tuna fishery. Marine Policy. 2000;24:109–117. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(99)00017-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cinner J. Coral reef livelihoods. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 2014;7:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AE, Frijters P, Shields MA. Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature. 2008;46:95–144. doi: 10.1257/jel.46.1.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CW, Clarke FH, Munro GR. The optimal exploitation of renewable resource stocks: Problems of irreversible investment. Econometrica. 1979;47:25–47. doi: 10.2307/1912344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CW, Munro GR, Sumaila UR. Subsidies, buybacks, and sustainable fisheries. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 2005;50:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2004.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coulthard S. What does the debate around social wellbeing have to offer sustainable fisheries? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 2012;4:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2012.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney, A. J., M. Kienzle, S. Pascoe, M. F. O’Neill, G. M. Leigh, Y.-G. Wang, J. Innes, M. Landers, A. J. Prosser, P. Baxter, and J. Larkin. 2012. Harvest strategy evaluations and co-management for the Moreton Bay Trawl Fishery. Report to the Australian Seafood CRC Project 2009/774. Brisbane: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Queensland.

- Courtney AJ, O’Neill MF, Braccini M, Leigh GM, Kienzle M, Pascoe S, Prosser AJ, Wang Y-G, Lloyd-Jones L, Campbell AB, Ives M, Montgomery SS, Gorring J. Biological and economic management strategy evaluations of the eastern king prawn fishery. Canberra: Fisheries Research and Development Corporation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins R. Personal income and subjective well-being: A review. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2000;1:133–158. doi: 10.1023/A:1010079728426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DAFF . East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery Interim 2011–12 Fishing Years Report. Brisbane: Queensland Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dichmont CM, Pascoe S, Jebreen E, Pears R, Brooks K, Perez P. Choosing a fishery’s governance structure using data poor methods. Marine Policy. 2013;37:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Inglehart R, Tay L. Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research. 2013;112:497–527. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0076-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer PD, King TJ, Minnegal M. Managing shark fishermen in southern Australia: A critique. Marine Policy. 2008;32:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2007.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher WJ, Chesson J, Sainsbury KJ, Hundloe TJ, Fisher M. A flexible and practical framework for reporting on ecologically sustainable development for wild capture fisheries. Fisheries Research. 2005;71:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2004.08.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frey BS, Stutzer A. Happiness and economics: How the economy and institutions affect human well-being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gatewood JB, McCay BJ. Job satisfaction and the culture of fishing: A comparison of six new Jersey Fisheries. MAST. Maritime Anthropological Studies. 1988;1:103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Grafton RQ, McIlgorm A. Ex ante evaluation of the costs and benefits of individual transferable quotas: A case-study of seven Australian commonwealth fisheries. Marine Policy. 2009;33:714–719. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2009.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernes H-K, Jentoft S, Mikalsen K. Fisheries governance, social justice and participatory decision-making. In: Gray T, editor. Participation in fisheries governance. Dordrecht: Springer; 2005. pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Holland D, Gudmundsson E, Gates J. Do fishing vessel buyback programs work: A survey of the evidence. Marine Policy. 1999;23:47–69. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(98)00016-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, N. A., and P. A. Marshall. 2007. Conceptualizing and operationalizing social resilience within commercial fisheries in northern Australia. Ecology and Society 12: 1 [online]. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art1/.

- Monnereau I, Pollnac R. Which fishers are satisfied in the Caribbean? A comparative analysis of job satisfaction among Caribbean lobster fishers. Social Indicators Research. 2012;109:95–118. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0058-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muallil RN, Geronimo RC, Cleland D, Cabral RB, Doctor MV, Cruz-Trinidad A, Alino PM. Willingness to exit the artisanal fishery as a response to scenarios of declining catch or increasing monetary incentives. Fisheries Research. 2011;111:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2011.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe S, Coglan L. Implications of differences in technical efficiency of fishing boats for capacity measurement and reduction. Marine Policy. 2000;24:301–307. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(00)00006-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe S, Dichmont CM, Brooks K, Pears R, Jebreen E. Management objectives of Queensland fisheries: Putting the horse before the cart. Marine Policy. 2013;37:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe S, Hutton T, van Putten I, Dennis D, Skewes T, Plagányi É, Deng R. DEA-based predictors for estimating fleet size changes when modelling the introduction of rights-based management. European Journal of Operational Research. 2013;230:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2013.04.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peiró A. Happiness, satisfaction and socio-economic conditions: Some international evidence. The Journal of Socio-Economics. 2006;35:348–365. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2005.11.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polinac R, Poggie JJ. Happiness, well-being, and psychocultural adaptation to the stresses associated with marine fishing. Human Ecology Review. 2008;15:194. [Google Scholar]

- Pollnac R, Bavinck M, Monnereau I. Job satisfaction in fisheries compared. Social Indicators Research. 2012;109:119–133. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0059-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan NC, Leung P. Modeling entry, stay, and exit decisions of the longline fishers in Hawaii. Marine Policy. 2004;28:311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2003.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quillérou, E., and O. Guyader. 2012. What is behind fleet evolution: A framework for flow analysis and application to the French Atlantic fleet. ICES Journal of Marine Science: Journal du Conseil.

- Skirtun M, Sahlqvist P, Curtotti R, Hobsbawn P. Australian fisheries statistics 2011. Canberra: ABARES; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Clay PM. Measuring subjective and objective well-being: Analyses from five marine commercial fisheries. Human Organization. 2010;69:158–168. doi: 10.17730/humo.69.2.b83x6t44878u4782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tella RD, MacCulloch R. Some uses of happiness data in economics. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20:25–46. doi: 10.1257/089533006776526111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tidd AN, Hutton T, Kell LT, Padda G. Exit and entry of fishing vessels: An evaluation of factors affecting investment decisions in the North Sea English beam trawl fleet. ICES Journal of Marine Science: Journal du Conseil. 2011;68:961–971. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsr015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, R. C., S. G. Sutton, A. Penny, L. Williams, J. Maroske, and J. Nilsson. 2010. Baseline socio-economic data for Queensland east-coast inshore and rocky reef fishery stakeholders. Part A: Commercial inshore and rocky reef fishers. Fishing and Fisheries Research Centre Technical Report No 5. Townsville: James Cook University.

- Triantafillos, L., K. Brooks, J. Schirmer, S. Pascoe, T. Cannard, C. M. Dichmont, O. Thebaud, and E. Jebreen. 2014. Developing and testing social objectives for fisheries management. FRDC Report—Project 2010/040. Adelaide, SA: Primary Industries and Regions.

- van Putten IE, Kulmala S, Thébaud O, Dowling N, Hamon KG, Hutton T, Pascoe S. Theories and behavioural drivers underlying fleet dynamics models. Fish and Fisheries. 2012;13:216–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2011.00430.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuri AW, Costanza R. The role of human, social, built, and natural capital in explaining life satisfaction at the country level: Toward a National Well-Being Index (NWI) Ecological Economics. 2006;58:119–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JM, Sutinen JG. Vessel entry–exit behavior in the Gulf of Mexico shrimp fishery. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 1994;76:916–923. doi: 10.2307/1243751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch H. Implications of happiness research for environmental economics. Ecological Economics. 2009;68:2735–2742. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]