Abstract

Brazil plans to build 43 “large” dams (>30 MW) in the Tapajós Basin, ten of which are priorities for completion by 2022. Impacts include flooding indigenous lands and conservation units. The Tapajós River and two tributaries (the Juruena and Teles Pires Rivers) are also the focus of plans for waterways to transport soybeans from Mato Grosso to ports on the Amazon River. Dams would allow barges to pass rapids and waterfalls. The waterway plans require dams in a continuous chain, including the Chacorão Dam that would flood 18 700 ha of the Munduruku Indigenous Land. Protections in Brazil’s constitution and legislation and in international conventions are easily neutralized through application of “security suspensions,” as has already occurred during licensing of several dams currently under construction in the Tapajós Basin. Few are aware of “security suspensions,” resulting in little impetus to change these laws.

Keywords: Amazonia, Brazil, Dams, Hydropower, Hydroelectric dams

Introduction

The Amazon Basin, roughly two-thirds of which is in Brazil, is the focus of a massive surge in hydroelectric dam construction, with plans that would eventually convert almost all Amazon tributaries into chains of reservoirs (e.g., Finer and Jenkins 2012; Kahn et al. 2014; Tundisi et al. 2014; Fearnside 2014a). Dams in tropical areas like Amazonia have a wide range of environmental and social impacts, including loss of terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity (Santos and Hernandez 2009; Val et al. 2010), greenhouse gas emissions (Abril et al. 2005; Kemenes et al. 2007; Fearnside and Pueyo 2012), loss of fisheries, and other resources that support local livelihoods (Barthem et al. 1991; Fearnside 2014b), methylation of mercury (rendering it poisonous to animals, including humans) (e.g., Leino and Lodenius 1995; Fearnside 1999), and population displacement (Cernea 1988, 2000; WCD 2000; McCully 2001; Scudder 2006; Oliver-Smith 2009, 2010). Dam projects throughout the tropics have followed a pattern of systematic violation of human rights, including violence and murder, especially involving indigenous peoples. Recent examples of murders of indigenous leaders opposing dams include Miguel Pabón in 2012 at the Hidrosogamoso Dam in Colombia and Onesimo Rodriguez in 2013 at the Barro Blanco Dam in Panama (Ross 2012; Yan 2013). The murder of two children (David and Ageo Chen) in 2014 at the Santa Rita Dam in Guatemala when the gunmen were unable to locate the leader they had been hired to kill has become an emblematic case (e.g., Illescas 2014). Ironically, all of these dams have projects for carbon credit approved by the Clean Development Mechanism and supposedly represent “sustainable development.” In Brazil, the killing of Adenilson Kirixi Mundurku by police in November 2012 is the emblematic case for indigenous peoples impacted by hydroelectric dams in the Tapajós River Basin (e.g., Aranha and Mota 2014). The Tapajós is a north-flowing Amazon tributary with a 764 183-km2 drainage basin. Brazil’s portion of the Amazon Basin is roughly the size of Western Europe, and the Tapajós Basin is about the size of Sweden and Norway together. Many of the challenges exemplified by the Tapajós plans apply throughout the world. As will be illustrated by the development plans in Brazil’s Tapajós River Basin, the decision-making process in Brazil and the legal system surrounding the country’s dam-building frenzy are stacked against the environment and the traditional Amazonian inhabitants.

The present paper concentrates on a little-discussed aspect of decision making and licensing for major development projects: the legal tools employed to neutralize protection for the environment and for human rights. Many other topics also require change to reduce the impacts and improve the benefits of developments such as those in Brazilian Amazonia. These include reform of energy policy and of the environmental impact assessment system, creation of mechanisms to prevent conflicts of interest for those who evaluate and decide on proposed infrastructure such as dams, and containing corruption both in its simple financial form and in its even more perverse political forms, including both illegal payoffs and legal campaign contributions (see Fearnside 2014a).

The theoretical framework used in the present study follows the pattern of identifying a limited set of objectives and then examining the critical points that prevent the objectives from being achieved. Frameworks that follow this principle are efficient in indicating priorities for change (e.g., Mermet 2011; Ostrom 2011). In this case, the objectives are both maintenance of Amazonian ecosystems (together with their environmental services) and maintenance of traditional populations (including indigenous peoples). Conflicts between hydroelectric plans and different kinds of protected areas, including indigenous lands, are documented. Other important aspects of Brazil’s development decisions, such as alternative means of providing the benefits of electricity to country’s population, are discussed elsewhere (e.g., Moreira 2012).

The Tapajós dams

A total of 43 “large” dams are either planned or under construction in Brazil’s Tapajós River Basin (Figs. 1, 2). “Large” dams in Brazil are defined as those with more than 30 megawatts (MW) of installed capacity. Nearly all of the planned dams are much larger than 30 MW. Three of these would be on the Tapajós River itself and four on the Jamanxim River (a tributary of the Tapajós in the state of Pará) (Table 1). On Tapajós tributaries in the state of Mato Grosso, six dams are planned in the Teles Pires River Basin (Table 2) and 30 in the Juruena River Basin (Table 3). There are also plans for numerous “small hydropower plants” (PCHs), meaning dams with installed capacity ≤30 MW that are exempted from the federal government’s Environmental Impact Study–Environmental Impact Report (EIA-RIMA).

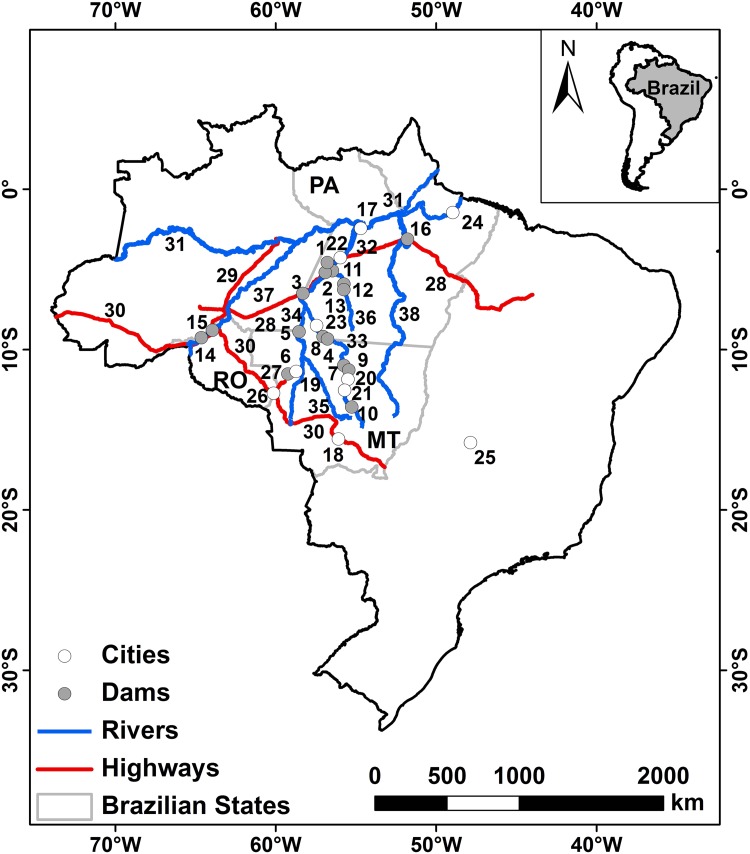

Fig. 1.

Brazil and locations mentioned in the text. Brazilian states: MT Mato Grosso, PA Pará, RO Rondônia. Dams: 1 São Luiz do Tapajós, 2 Jatobá, 3 Chacorão, 4 Teles Pires, 5 Salto Augusto Baixo, 6 São Simão Alto, 7 Colíder, 8 São Manoel, 9 Sinop, 10 Magessi, 11 Cachoeira do Caí, 12 Cachoeira dos Patos, 13 Jardim de Ouro, 14 Jirau, 15 Santo Antônio, 16 Belo Monte. Cities: 17 Santarém, 18 Cuiabá, 19 Juína, 20 Sinop, 21 Sorriso, 22 Itaituba, 23 Miritituba, 24 Barcarena, 25 Brasília, 26 Vilhena. Highways: 27 MT-319, 28 BR-230, 29 BR-319, 30 BR-364. Rivers: 31 Amazon, 32 Tapajós, 33 Teles Pires, 34 Juruena, 35 Arinos, 36 Jamanxim, 37 Madeira, 38 Xingu

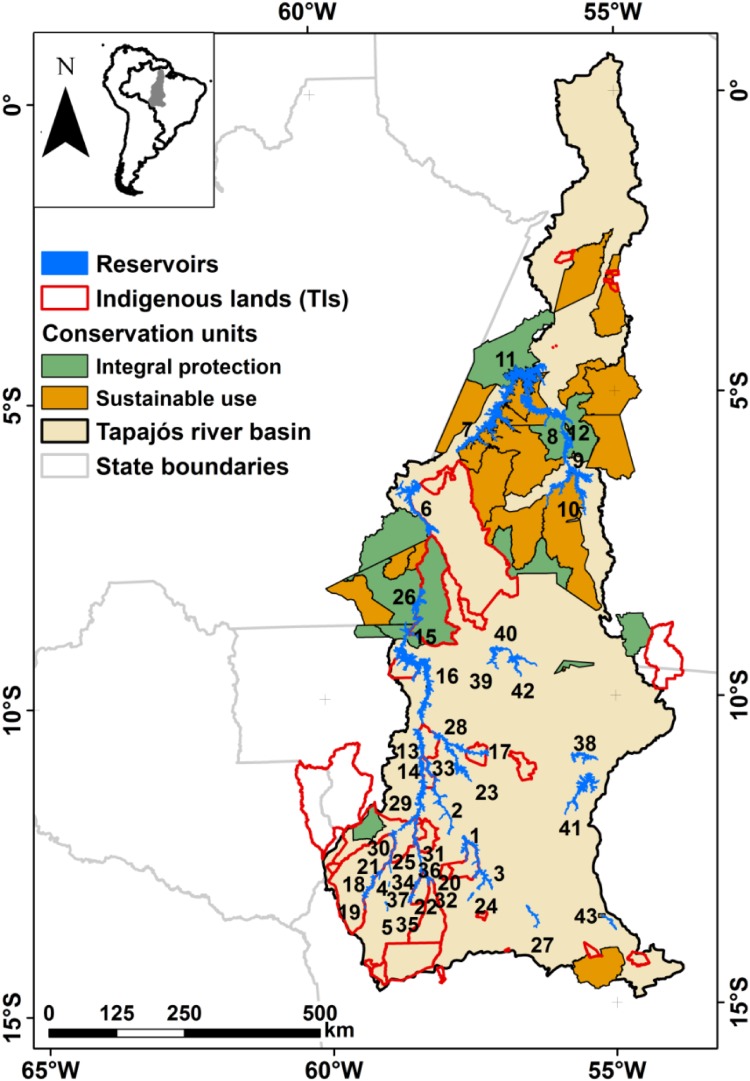

Fig. 2.

Large dams (>30 MW) planned in the Tapajós Basin: 1 Roncador, 2 Kabiara, 3 Parecis, 4 Cachoeirão, 5 Juruena, 6 Chacorão, 7 Jatobá, 8 Cachoeira do Caí, 9 Cachoeira dos Patos, 10 Jardim de Ouro, 11 São Luiz do Tapajós, 12 Jamanxim, 13 Tucumã, 14 Erikpatsá, 15 Salto Augusto Baixo, 16 Escondido, 17 Apiaka Kayabi, 18 Jacare, 19 Pocilga, 20 Foz do Sacre, 21 Foz do Formiga Baixo, 22 Salto do Utiariti, 23 Castanheira, 24 Paiaguá, 25 Nambiquara, 26 São Simão Alto, 27 Barra do Claro, 28 Travessão dos Índios, 29 Fontanilhas, 30 Enawene Nawe, 31 Foz do Buriti, 32 Matrinxã, 33 Tapires, 34 Tirecatinga, 35 Água Quente, 36 Buriti, 37 Jesuíta, 38 Colíder, 39 Foz do Apiacás, 40 São Manoel, 41 Sinop, 42 Teles Pires, 43 Magessi

Table 1.

Planned dams on the Tapajós and Jamanxim Rivers

| No. in Fig. 2 | Name | Code | River | Power (MW)a,b | Reservoir Area (km2) b | Status | Inclusion in waterway | Inclusion in PDE 2013–2022a | Indigenous areas affected | Conservation units affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Jatobá | TPJ-445 | Tapajós | 2338 | 646 | Planned | Yes | Yes | Munduruku areas not officially recognizedc | Amanã National Forest |

| 6 | Chacorão | TPJ-685 | Tapajós | 3336 | 616 | Planned | Yes | No | TI Munduruku | |

| 8 | Cachoeira do Caí | JMX-043 | Jamanxim | 802 | 420 | Planned | No | No | Itaituba-II National Forest | |

| 9 | Cachoeira dos Patos | JMX-166 [J] | Jamanxim | 528 | 117 | Planned | No | No | Parque Nacional do Jamanxim, Jamanxim National Forest | |

| 10 | Jardim de Ouro | JMX-257 | Jamanxim | 227 | 426 | Planned | No | No | Jamanxim National Forest | |

| 11 | São Luiz do Tapajós | TPJ-325 | Tapajós | 6133 | 722 | Planned | Yes | Yes | Munduruku areas not officially recognizedc | Amazonia National Park, Itaituba-I National Forest, Itaituba-II National Forest |

| 12 | Jamanxim | JMX-212 | Jamanxim | 881 | 75 | Planned | No | No | Jamanxim National Park |

Table 2.

Planned dams in the Teles Pires Basin

| No. in Fig. 2 | Namea | Code | River | Power (MW)a | Reservoir Area (km2)b | Status | Inclusion in waterway | Inclusion in PDE 2013–2022 | Indigenous areas affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | Colíder | TPR-680 | Teles Pires | 300 | 171.7 | Under construction | Yes | Yes | |

| 39 | Foz do Apiacás (Salto Apiacás) | API-006 | Apiacás | 230 | 89.6 | Planned | No | Yes | Kaiabí |

| 40 | São Manoel | TPR-287 | Teles Pires | 700 | 53 | Under construction | Yes | Yes | Kaiabí |

| 41 | Sinop | TPR-775 | Teles Pires | 400 | 329.6 | Under construction | Yes | Yes | |

| 42 | Teles Pires | TPR-329 | Teles Pires | 1820 | Under construction | Yes | Yes | ||

| 43 | Magessi | TPR-1230 | Teles Pires | 53 | 60 | Planned | No | No |

Table 3.

Planned dams in the Juruena Basin

| No. in Fig. 2 | Namea,c | Code | River | Power (MW)a | Inclusion in waterway | Inclusion in PDE 2013–2022b | Indigenous areas affectedc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roncador | do Sangue | 134.0 | No | No | TI Manoki | |

| 2 | Kabiara | do Sangue | 241.2 | No | No | TI Erikpatsá | |

| 3 | Parecis | do Sangue | 74.5 | No | No | TI Manoki | |

| 4 | Cachoeirão | Juruena | 64.0 | No | No | ||

| 5 | Juruena | Juruena | 46.0 | No | No | ||

| 13 | Tucumã | JRN-466 | Juruena | 510 | Yes | No | TI Japuira |

| 14 | Erikpatsá | JRN-530 | Juruena | 415 | Yes | No | TI Erikpatsá |

| 15 | Salto Augusto Baixo | JRN-234b | Juruena | 1461 | Yes | Yes | |

| 16 | Escondido | JRN-277 | Juruena | 1248 | Yes | No | TI Escondido |

| 17 | Apiaká-Kayabi | PEX-093 | dos Peixes | 206 | No | No | |

| 18 | Jacaré | JUl-048 | Juína | 53 | No | No | TI Nambikwara |

| 19 | Pocilga | JUl-117 | Juína | 34 | No | No | TI Nambikwara |

| 20 | Foz do Sacre | PPG-147 | Papagaio | 117 | No | No | TI Tirecatinga |

| 21 | Foz do Formiga Baixo | JUl-029b | Juína | 107 | No | No | TI Nambikwara |

| 22 | Salto Utiariti | PPG-159 | Papagaio | 76 | No | No | TI Tirecatinga |

| 23 | Castanheira | ARN-120 | Arinos | 192 | Yes | Yes | |

| 24 | Paiaguá | do Sangue | 35.2 | No | No | TI Manoki; TI Ponte de Pedra | |

| 25 | Nambiquara | JUl-008 | Juína | 73 | No | No | TI Nambikwara |

| 26 | São Simão Alto | JRN-117a | Juruena | 3509 | Yes | Yes | |

| 27 | Barra do Claro | Arinos | 61.0 | No | No | ||

| 28 | Travessão dos Índios | Juruena | 252 | No | No | ||

| 29 | Fontanilhas | JRN-5771 | Juruena | 225 | No | No | |

| 30 | Enawenê-Nawê | JRN-7201 | Juruena | 150 | No | No | |

| 31 | Foz do Buriti | PPG-1151 | Papagaio | 68 | No | No | |

| 32 | Matrinxã | SAC-0141 | Sacre | 34.5 | No | No | |

| 33 | Tapires | SAN-0201 | do Sangue | 75 | No | No | |

| 34 | Tirecatinga | BUR-0391 | Burití | 37.5 | No | No | |

| 35 | Água Quente | BUR-077 | Burití | 42.5 | No | No | |

| 36 | Buriti | BUR-0131 | Burití | 60 | No | No | |

| 37 | Jesuíta | Juruena | 22.3d | No | No |

aSource of data on dams: Brazil, ANEEL (Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica) (2011); several of the installed capacities listed reflect downward revisions by ANEEL as compared to initial proposals

bTen-Year Energy Expansion Plan (Plano Decenal de Expansão de Energia: PDE) 2013–2022: Brazil, MME (2013, pp. 84-85)

cCNEC Worley Parsons Engenharia, S.A. (2014a, Fig. 35-1. Illustration 3.5/1)

dListed as a large dam, but with currently expected installed capacity <30 MW

Brazil’s Second Program for the Acceleration of Growth (PAC-2), covering the 2011–2015 period, includes six dams on the Tapajós and Jamanxim Rivers and five dams on the Teles Pires River (Brazil, PR 2011). Priorities and schedules for dams have been evolving continuously, as indicated by the Ten-Year Energy Expansion Plans (PDEs) launched every year by the Ministry of Mines and Energy, containing the dams planned for the succeeding ten years. For example, the dams on the Jamanxim River appeared in the PDEs through the 2011–2020 Plan but disappeared from subsequent plans, meaning that they were postponed to beyond the ten-year horizon. They were replaced by the São Simão Alto and Salto Augusto Baixo mega-dams on the Juruena River, plus smaller dams such as Castanheira, on the Arinos River, which is a tributary of the Juruena and the location of one of the ports planned for loading soybeans onto the barges that would descend the Tapajós Waterway (Brazil, MME 2013). These changes favor dams that comprise the waterways that are planned to transport soybeans and postpone the dams that are not part of these routes. The Ministry of Mines and Energy does not build locks, its contribution to the waterways being limited to reserving space for this purpose next to each dam and locks being the purview of Ministry of Transportation. Although the two ministries are not always in agreement on priorities, the final word lies with the “Civil House” (Casa Civil) of the president’s office.

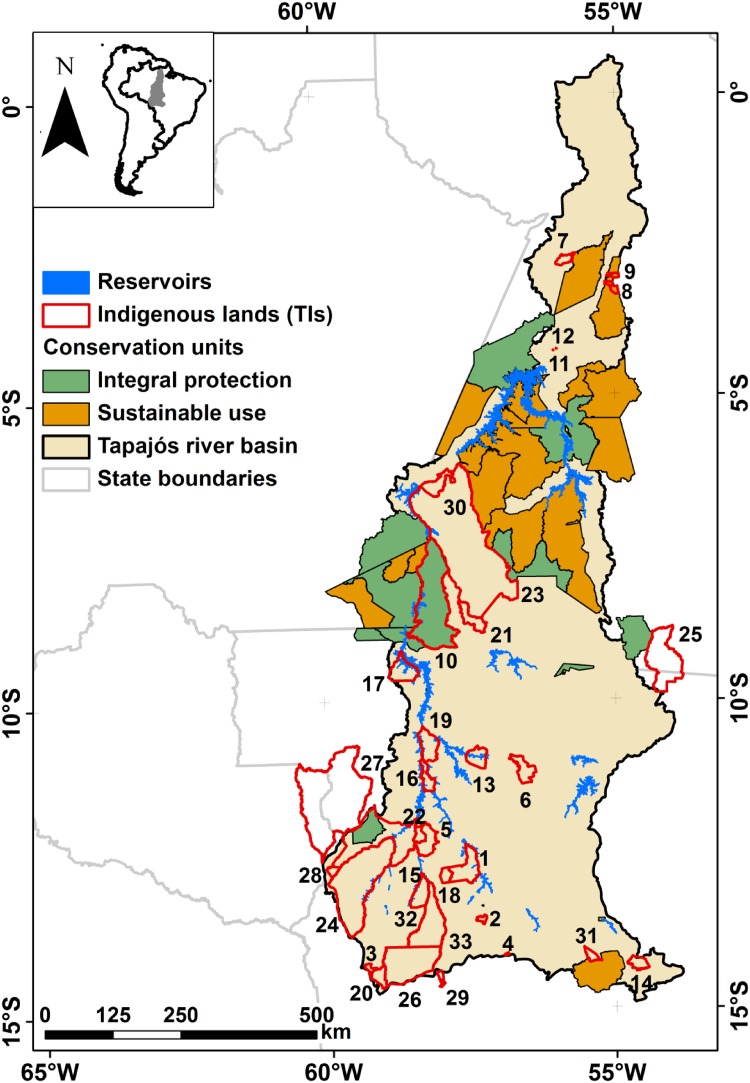

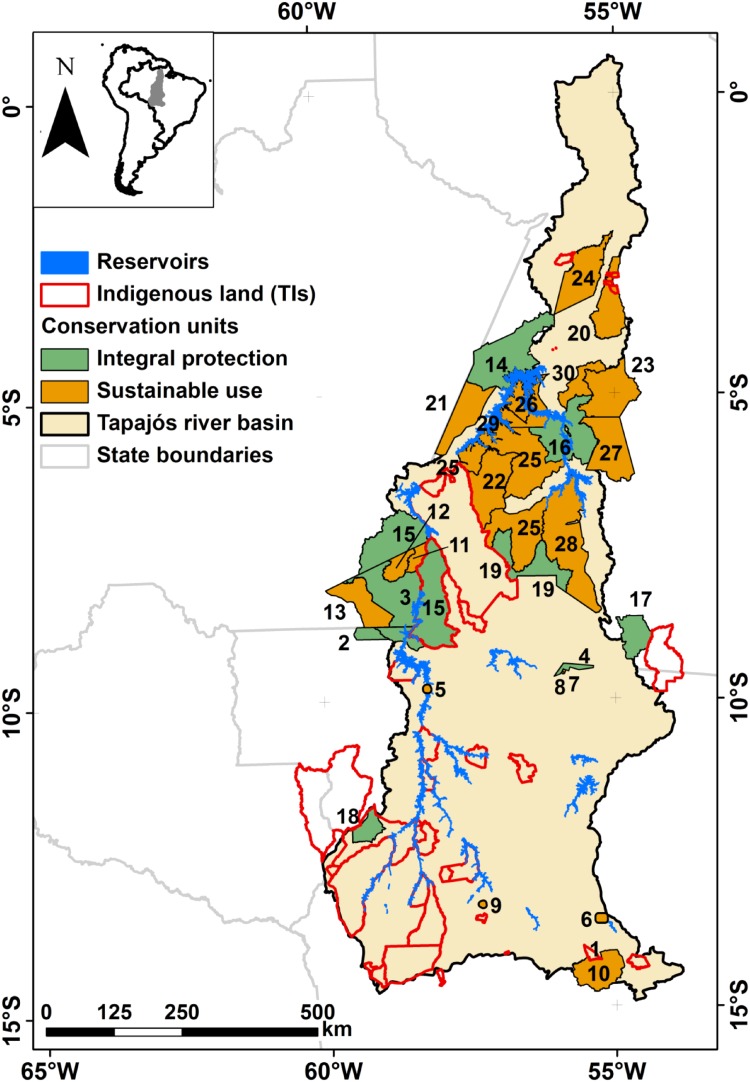

Of the 43 planned dams planned in the Tapajós Basin, ten are included in the 2013–2022 PDE: two on the Tapajós River itself and five in the Teles Pires Basin and three in the Juruena Basin (Tables 1, 2, 3). The dams have multiple impacts, including damage to indigenous lands (“terras indígenas”, or “TIs”) (Fig. 3) and flooding in conservation units (CUs) (Fig. 4). Note that in Brazil, “conservation units” refer to protected areas of types included in the National System of Conservation Units (SNUC) (Brazil, PR 2000). Other types of protected areas, such as indigenous lands, are also important for maintaining Amazonian forest. Dams expel riverside populations and drive deforestation in various ways.

Fig. 3.

Indigenous lands (Terras Indígenas: TIs) in the Tapajós Basin: 1 Manoki, 2 Ponte de Pedra, 3 Uirapuru, 4 Estação Parecis, 5 Menkú, 6 Batelão, 7 Maró, 8 Munduruku-Taquara, 9 Bragança-Marituba, 10 Apiaká do Pontal e Isolados, 11 Praia do Índio, 12 Praia do Mangue, 13 Apiaká/Kayabi, 14 Bakairi, 15 Enawenê-Nawê, 16 Erikpatsá, 17 Escondido, 18 Irantxe, 19 Japuira, 20 Juininha, 21 Cayabi, 22 Menkú, 23 Munduruku, 24 Nambikwara, 25 Panará, 26 Paresi, 27 Parque do Aripuanã, 28 Pirineus de Souza, 29 Rio Formoso, 30 Sai-Cinza, 31 Santana, 32 Tirecatinga, 33 Utiariti

Fig. 4.

Conservation units in the Tapajós Basin. 1 Águas do Cuiabá State Park, 2 Igarapés do Juruena State Park, 3 Sucunduri State Park, 4 Cristalino State Park, 5 Peugeot-ONF-Brasil Private Reserve of Natural Patrimony (RPPN), 6 Área de Proteção Ambiental do Salto Magessi, 7 Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Natural Cristalino-I RPPN, 8 Cristalino-III RPPN, 9 Fazenda Loanda RPPN, 10 Cabeceiras do Rio Cuiabá Environmental Protection Area (APA), 11 Bararati Sustainable Development Reserve, 12 Apuí State Forest, 13 Sucunduri State Forest, 14 Amazonia National Park, 15 Juruena National Park, 16 Jamanxim National Park, 17 Nascentes Serra do Cachimbo Biological Reserve, 18 Iquê Ecological Station, 19 Rio Novo National Park, 20 Tapajós National Forest, 21 Amaná National Forest, 22 Crepori National Forest, 23 Riozinho do Anfrísio Extractive Reserve, 24 Tapajós Arapiuns Extractive Reserve, 25 Tapajós APA, 26 Itaituba-II National Forest, 27 Altamira National Forest, 28 Jamanxim National Forest, 29 Itaituba-I National Forest, 30 Trairão National Forest

Flooding of land in protected areas is one of the environmental impacts of planned dams in the Tapajós Basin. The Brazilian government has degazetted parts of several conservation units even before the planned dams have been evaluated and licensed. Part of Amazonia National Park has already been degazetted (removing legal protection) by means of a provisional measure (No. 558/2012), subsequently converted into law (No. 12 678/2012). This was done explicitly to make way for the reservoir of the São Luiz do Tapajós Dam (e.g., IHU 2012; WWF Brasil 2012). The federal government also removed part of the Juruena National Park to make way for the São Simão Alto and Salto Augusto Baixo Dams on the Juruena River (WWF Brasil 2014). The planned dams would inundate 15 600 ha of Amazonia National Park, 18 515 ha of Jamanxim National Park, 7352 ha of Itaituba-I National Forest, 21 094 ha of Itaituba-II National Forest and 15 819 ha of the Tapajós Environmental Protection Area (APA), or a total of 78 380 ha in protected areas.

In the case of the Tapajós River Basin, the impact of many dams and the Tapajós Waterway, including its branches on the Teles Pires and Juruena Rivers, is much larger than the damage that usually comes into discussion for any specific project, such as the first planned dam, São Luiz do Tapajós (CNEC Worley Parsons Engenharia 2014a, b). The waterway has a key role in ensuring construction of all dams required to make the route navigable, including the most damaging dam, Chacorão.

The Tapajós waterway

Dams flood rapids that impede navigation and the locks associated with the dams allow the passage of barges. Brazil has extensive plans for inland navigation (Fearnside 2001, 2002; Brazil, PR 2011). These dams would allow the Tapajós Waterway to carry soybeans from Mato Grosso to ports in Santarém, Santana, and Barcarena, thus giving access to the Amazon river and the Atlantic Ocean (Brazil, PR 2011; Millikan 2011).

Completion of the waterway would require an additional dam that is not mentioned in the “energy axis” of PAC-2. This is the Chacorão Dam on the Tapajós River in the state of Pará (e.g., Millikan 2011). Chacorão also does not appear among the dams listed in the PDEs for 2011–2020, 2012–2021, and 2013–2022 (e.g., Brazil, MME 2013). On the other hand, Chacorão appears in the feasibility study for the São Luiz do Tapajós Dam (CNEC Worley Parsons Engenharia 2014a). It also appears in the Integrated Environmental Assessment (AAI) for the Tapajós dams (Grupo de Trabalho Tapajós, and Ecology Brasil 2014, p. 60). The locks associated with Chacorão are listed as a “priority” in the National Waterways Plan (Brazil, MT 2010, p. 22). The reservoir behind the dam would allow barges to cross the Chacoráo rapids.

Chacorão would inundate 18 700 ha of the Munduruku Indigenous Land (Millikan 2011). In the case of the São Luiz do Tapajos and Jatobá Dams, the reservoirs would flood Munduruku tribal lands that have not been officially designated as an “indigenous land” (Ortiz 2013; Lourenço 2014). Creation of new indigenous lands in Brazil has been “paralyzed” for several years, reportedly due to orders from above that the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) does not deny (e.g., CIMI 2014). This “paralyzation” appears to represent a policy to facilitate the flooding of areas inhabited by indigenous populations where indigenous lands have not yet been created, such as the Munduruku populations in the areas that would be flooded by the planned São Luiz do Tapajós and Jatobá Dams. This is clear in a video of Maria Augusta Assirati, the “president” (head) of FUNAI, in tears as she tries to explain to a group of Mundurku in September 2014 that the paperwork for creating their reserve was completely ready for her signature and had been sitting on her desk for a year, but that “other government agencies began to discuss the proposal” because of the hydroelectric plans (Amigos da Terra-Amazônia Brasileira 2014). She was replaced as head of the agency 9 days later with the paperwork still unsigned and, later, she confirmed the interference (Aranha 2015).

Implementation of the Tapajós Waterway would encourage future deforestation for soy in the northern part of Mato Grosso, which would be served by this infrastructure complex. The waterway would also encourage soy plantations in the cattle pastures that currently dominate land use in areas that have already been cleared in this part of Mato Grosso. Such a conversion causes deforestation indirectly in other places: both the cattle and the ranchers who sell their land to soy planters (“sojeiros”) move from Mato Grosso to Pará (Fearnside 2001). The effect on deforestation in Pará from advancement of soy in pastures in Mato Grosso has been shown statistically (Arima et al. 2011). This effect has been denied by Brazilian diplomats, who were successful in getting the mention of it removed from the summary for policy makers of the Fifth Assessment Report (AR-5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in March 2014 (Garcia 2014). Stimulus to deforestation by the Tapajós Waterway is not included among impacts considered in environmental licensing and in evaluating greenhouse gas emissions of projects for generating carbon credits from dams in the Tapajós Basin, as in the case of the Teles Pires Dam (Fearnside 2013).

On April 25, 2014, Bunge, a multinational company currently responsible for 25 % of Brazil’s soy production, opened a port for export of soybeans in Barcarena, at the mouth of the Amazon River. The company expects Brazil’s exports to double by 2024, mainly targeting China (Freitas 2014). Soybeans for the first vessel loaded at the port of Vila de Conde (in Barcarena) came from Mato Grosso in trucks to the port of Miritituba (on the lower Tapajós River), and from there proceeded to Barcarena in barges operated by Navegações Unidas Tapajós Ltda. (Unitapajós), a joint venture between the Amaggi and Bunge companies. In the future, it is expected that the soybeans exported from Barcarena will travel all the way from Mato Grosso on barges descending the Tapajós Waterway, starting with the branch of the waterway on the Teles Pires River.

The portion of the waterway in the state of Mato Grosso will fork, with one branch on the Teles Pires River and the other on the Juruena. The first branch of the Tapajós Waterway to be built would make the Teles Pires River navigable as far as Sinop, and, subsequently, to Sorriso. The Teles Pires branch requires a series of five dams, three of which (Colider, São Manoel and Sinop) are already under construction. The São Manoel Dam is less than 1 km from the Kayabi Indigenous Land and already has provoked conflicts with the tribe (ISA 2013). The Foz do Apiacás Dam is located only 5 km from the same indigenous area. Interministerial Ordinance 419/2011 considers that indigenous areas are affected by any hydroelectric plant within 40 km.

For the second branch of the waterway, which would be built on the Juruena River, soybeans would reach the two planned ports via roads from the south, including a new road (MT-319) that would connect Juína, Mato Grosso, with Vilhena, in eastern Rondônia, bisecting two indigenous areas: TI Enawenê Nawê and the Aripunã Indigenous Park (Macrologística 2011). The Juruena River branch of the waterway requires six dams to reach the proposed ports, and three of the reservoirs would flood in the indigenous lands: the Escondido and Erikpatsá Dams would flood in TIs with the same names, and the Tucumã Dam would flood part of TI Japuira (CNEC Worley Parsons Engenharia 2014a, Illustration 3.5/1). Sixteen more dams are planned on the tributaries in the headwaters of the Juruena above the portion of the river to be made navigable (Brazil, ANEEL 2011). Of the 16 “large” dams in the headwaters of the Juruena, four affect TI Nambikwara (Poçilga, Jacaré, Foz do Formiga Baixo and Nambikwara), and two affect TI Tirecatinga (Salto Utiariti and Foz do Sacre) (CNEC Worley Parsons Engenharia 2014a). A number of “small hydropower plants” (PCHs) are also planned, several of which affect the indigenous areas (CNEC Worley Parsons Engenharia 2014a, Illustration 3.5/1; de Almeida 2010; Fanzeres 2013).

Laws overriding protection

Legal treatment of licensing, and especially of impacts on indigenous peoples, provides a clear illustration of the barriers preventing implementation of protections specified in Brazil’s constitution and legislation. This also applies to international agreements such as Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO-169), under which indigenous peoples impacted by development projects have the right to “consultation.” Unfavorable decisions on dam construction in Brazil are routinely reversed by invoking a “security suspension” (“suspensão de segurança”) that allows construction to continue regardless of any social or environmental violations if halting the project would cause grave damage to the “public economy.” A law originating from Brazil’s military dictatorship authorizes

the President of the Court to suspend the execution of injunctions and rulings on claims against public authorities and their agents in order to avoid serious injurytothe public economy (Law No. 4348 of 26 June 1964; replaced by Law 12 016 of August 7, 2009). [emphasis added]

After Brazil’s 1988 Constitution created the Public Ministry (a public prosecutor’s office charged with defending the interests of the people), applicability of security suspensions was reconfirmed by clarifying that

it is the responsibility of the President of the Court, to whom an appeal [“recurso”] is submitted, to suspend, by means of a substantiated order, the execution of injunctions in claims against public authorities or their agents, at the request of the Public Ministry or of any concerned legal entity governed by public law, in the event of manifest public interest and blatant unlawfulness, and to avoid serious injury to the public order, health, safety and economy (Art. 4 of Law 8437 of June 30, 1992). [emphasis added]

It was clarified that no subsequent appeal (“agravo”) could have the effect of temporarily reverting a security suspension:

When, at the request of an interested legal entity governed by public law or the Public Ministry, and to avoid serious injury to the public order, health, security and economy, the President of the Court to which the respective appeal [“recurso”] is submitted suspends, by means of a substantiated decision, the execution of the injunction and the sentence, this decision is subject to interlocutory appeal [“agravo”], without any suspensory effect, within five days, which will be judged in the session following its filing (Art. 15 of Law 12 016 of August 7, 2009). [emphasis added]

Of course, any hydroelectric dam has economic importance, thus effectively negating all protections of the environment and of impacted peoples (e.g., Prudente 2013, 2014).

In the case of the Teles Pires Dam, use of the security suspension was denounced before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) of the Organization of American States (OAS), on March 28, 2014 (ISA 2014). The Teles Pires Dam affects three indigenous tribes (Kayabi et al. 2011). Loss of fishing will affect the Kayabi’s nutrition. The group will also lose sacred sites associated with waterfalls to be flooded. The licensing process contained a variety of irregularities (Millikan 2012). Successive legal attempts to stop the dam were reversed, usually in just two or three days. The speed with which decisions are reversed despite extensive documentation of impacts and of violations of laws is probably due to the fact that a security suspension is independent of arguments concerning the impacts and legality of a project, depending only on demonstrating the project’s economic importance. The Teles Pires Dam was suspended on December 14, 2010 (Kayath 2010), on March 27, 2012 (Lessa 2012; MPF/PA 2012), on April 9, 2012 (Menezes 2012a) and on August 1, 2012 (see Fiocruz and Fase 2013), and on October 9, 2013 (TRF-1 2013). On November 11, 2014, for the 12th time in the case of the Tapajós Dams, a security suspension was granted. This allowed the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) to issue an operating license to the Teles Pires Dam without the dam consortium having complied with many of the conditions that IBAMA had previously established (Palmquist 2014).

Licensing of the São Manoel Dam has produced spectacular chronology irregularities (Monteiro 2013a, b). Several attempts to prevent construction were legally reversed. A suspension of bidding for construction contracts was reversed on December 13, 2013 (Fiocruz and Fase 2013). On April 28, 2014 a judge in Cuiabá suspended work on São Manoel based on legislation guaranteeing the rights of indigenous peoples (Presser 2014). Meanwhile, a public civil suit against São Manoel, which was initiated on September 17, 2013, reached the “concluded for sentencing” stage on July 21, 2014 (TRF-1 2014).

The Sinop, Colíder and Magessi Dams had their construction blocked on December 6, 2011 when a judge in Sinop issued a preliminary injunction based on violation of legislation on environmental licensing (da Silva Neto 2011). Among other irregularities, licensing was being done only by the Mato Grosso Environment Secretariat, while dams such as these require licensing at the federal level by IBAMA (MPF/PA 2011). The dams in question impact indigenous peoples (Monteiro 2011). As early as January 16, 2012 a judge in Brasilia rejected the suit based on a security suspension (Menezes 2012b), allowing construction to continue. As in any country, interpretation of laws varies with individual judges, and some are more prone than others to decide in favor of economic concerns over indigenous rights or environmental impacts. This subset of judges is often sought out by government attorneys in appeals to overturn decisions on dams, even though the judges in question may be located far from the dams in question (see example in Fearnside and Barbosa 1996).

The existence of laws authorizing “security suspensions” is not generally known either to the academic community or to the Brazilian public. Discussion of the need to change these laws is therefore almost nonexistent. The same lack of awareness applies to high-impact projects like the Chacorão Dam, which is omitted from virtually all public discussion of the Tapajós Basin developments despite being a key part of the overall plan. Omitting discussion of the most controversial components of Brazil’s hydroelectric plans represents a general pattern, repeating the recent history of licensing the Santo Antônio and Jirau Dams on the Madeira River (Fearnside 2014c) and the Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River (Fearnside 2006, 2012).

While discussion is invariably concentrated on the pros and cons of each individual proposed project, the way that decisions are made is much more fundamental to the environmental and social conditions that will prevail in the future. The interdependence of project complexes like dams and waterways is a part of this little-debated area. Another is the underlying legal structure, which in the case of Brazil represents a “safety net” for project proponents that provides an ultimate guarantee against environmental and social limitations. Those in the environmental field who have worked long and hard to build the impact assessment and licensing system usually view the legal system as a given part of the institutional landscape that must simply be accepted. Fortunately, national laws are not natural laws, and they are subject to change by social decisions. This is true in any country, Brazil providing an example.

Conclusions

The plans for dams and waterways in the Tapajós Basin imply large impacts, both individually and together. These impacts include damage to indigenous lands and to protected areas. The combination of proposals for dams and waterways implies impacts that could otherwise not occur. An example is provided by the Chacorão Dam, which would flood part of the Munduruku Indigenous Land; this dam might not be a priority if it were not part of the route of the Tapajós Waterway. Brazil’s environmental licensing system has been unable to prevent the approval of projects with large impacts, and the legal system has been unable to enforce constitutional and other protections due to the existence of laws authorizing “security suspensions” to allow the continuation of any construction project with economic importance. Public discussion is needed of the laws that currently guarantee completion of any dam or other large infrastructure project irrespective of environmental and social impacts and violations of licensing requirements. Disclosure and democratic debate are also needed on the full range of components comprising basin development plans, including high-impact projects like the Chacorão Dam that are now virtually absent from public view. The immediate policy recommendation arising from the Tapajós experience is obvious: repeal laws or portions of laws (e.g., Article 15 of Law 12 016 of August 7, 2009) authorizing “security suspensions” and allow Brazil’s existing environmental licensing system to function. On a wider scale, those concerned with the environmental and social impacts of development in every country need to work to purge aberrations of this kind from their legal and regulatory systems.

Acknowledgments

The author’s research is financed exclusively by academic sources: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq: proc. 2007-1/305880, 304020/9/2010-573810, 2008-7, 575853/2008-5), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas (FAPEAM Proc—708565) and Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA: JRP 13.03). Part of this text is translated and adapted from (Fearnside 2014a). Zachary Hurwitz, of International Rivers, provided shape files used in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4, which were prepared by Marcelo dos Santos. A Portuguese language text presenting the information included here will be available in a compendium to be organized by International Rivers, Brazil on dams in the Tapajós Basin. P.M.L.A. Graça, D. Alarcon, I.F. Brown and two anonymous reviewers provided valuable comments.

Philip M. Fearnside

is a Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon (INPA) in Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil since 1978. His work has been organized around the objective of converting the environmental services of Amazonian forests into a basis for sustainable development for the rural population of the region, taking the place of the current pattern of forest destruction. He has studied the environmental impacts of more than ten hydroelectric dams, as well as the decision-making and licensing processes for these and other infrastructure projects in Amazonia (see http://philip.inpa.gov.br).

References

- Abril G, Guérin F, Richard S, Delmas R, Galy-Lacaux C, Gosse P, Tremblay A, Varfalvy L, dos Santos MA, Matvienko B. Carbon dioxide and methane emissions and the carbon budget of a 10-years old tropical reservoir (Petit-Saut, French Guiana) Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 2005;19:GB 4007. doi: 10.1029/2005GB002457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amigos da Terra-Amazônia Brasileira. 2014. Funai admite pressão e condiciona demarcação à hidrelétrica [FUNAI admits to be pressured and makes demarcation conditional on the hydroelectric dam (in Portuguese)]. Notícias. Retrieved 26 November 2014, from http://amazonia.org.br/2014/11/funai-admite-press%C3%A3oe-condiciona-demarca%C3%A7%C3%A3o-%C3%A0-hidrel%C3%A9trica/.

- Aranha, A., and J. Mota. 2014. Mundukurus lutam por sua terra e contra hidrelétrica Tapajós. Pública, Agência de Reportagem e Jornalismo Investigativo. Retrieved, from http://jornalggn.com.br/blog/mpaiva/mundukurus-lutam-por-sua-terra-e-contra-hidreletrica-tapajos.

- Aranha, A. 2015. “A Funai está sendo desvalorizada e sua autonomia totalmente desconsiderada”, diz ex-presidente [“FUNAI is being devalued and its autonomy totally ignored” says the ex-president (in Portuguese)]. Publica Agência de Reportagem e Jornalismo Investigativo. Retrieved January 27, 2015, from http://apublica.org/2015/01/a-funai-esta-sendo-desvalorizada-e-sua-autonomia-totalmente-desconsiderada-diz-ex-presidente/.

- Arima EY, Richards P, Walker R, Caldas MM. Statistical confirmation of indirect land use change in the Brazilian Amazon. Environmental Research Letters. 2011;6:024010. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/6/2/024010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barthem RB, Ribeiro MCBL, Petrere M. Life strategies of some long-distance migratory catfish in relation to hydroelectric dams in the Amazon Basin. Biological Conservation. 1991;55:339–345. doi: 10.1016/0006-3207(91)90037-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brazil, ANEEL (Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica). 2011. Processo nº 48500.001701/2006-11. Assunto: Análise dos Estudos de Inventário Hidrelétrico da bacia do rio Juruena, localizado na subbacia 17, nos Estados de Mato Grosso e Amazonas [Case No. 48500.001701/2006-11. Subject: Analysis of the hydroelectric inventory studies of the Juruena River Basin (in Portuguese)] Nota Técnica no, 297/2011—SGH/ANEEL, de 05/-8/2011. Brasília, DF: ANEEL.

- Brazil, MME (Ministério das Minas e Energia). 2013. Plano Decenal de Expansão de Energia 2022 [Ten-Year Energy Expansion Plan 2022 (in Portuguese)]. Brasília, DF: MME, Empresa de Pesquisa Energética (EPE). Retrieved, from http://www.epe.gov.br/PDEE/20140124_1.pdf.

- Brazil, MT (Ministério dos Transportes). 2010. Diretrizes da Política Nacional de Transporte Hidroviário. [Guidelines of the National Waterway Transport Policy (in Portuguese)] Brasília, DF, Brazil: MT, Secretaria de Política Nacional de Transportes. Retrieved, from http://www2.transportes.gov.br/Modal/Hidroviario/PNHidroviario.pdf.

- Brazil, PR (Presidência da República). 2000. Lei nº 9.985, de 18 de julho de 2000 [Law No. 9985 of July 18, 2000 (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved, from http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9985.htm.

- Brazil, PR (Presidência da República). 2011. PAC-2 Relatórios [Reports (in Portuguese)]. PR, Brasília, DF. Retrieved, from http://www.brasil.gov.br.

- Cernea, M.M. 1988. Involuntary resettlement in development projects: policy guidelines in World Bank-Financed Projects (World Bank Technical Paper No. 80), 88 pp. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Retrieved, from http://rru.worldbank.org/documents/toolkits/highways/pdf/91.pdf.

- Cernea, M.M. 2000. Impoverishment risks, safeguards, and reconstruction: A model for population displacement and resettlement. In Risks and reconstruction. Experiences of resettlers and refugees, ed. M. Cernea, and C. McDowell, 504 pp. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- CIMI (Comissão Indigenista Missionária). 2014. Enquanto Funai admite orientação para paralisar demarcações, relatório demonstra efeitos da política governista [While Funai admits being told to paralyze demarcations, report shows effects of government policy (in Portuguese)]. Amazônia, July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014 (15:36:27), from http://amazonia.org.br/2014/07/enquanto-funai-admite-orientacao-para-paralisar-demarcacoes-relatorio-demonstra-efeitos-da-politica-governista/.

- CNEC Worley Parsons Engenharia, S.A. 2014a. Estudo de Viabilidade do AHE São Luiz do Tapajós. [Viability study of the São Luiz do Tapajós hydroelectric dam (in Portuguese)] São Paulo, SP: CNEC (Consórcio Nacional dos Engenheiros Consultores), 11 Vols. + attachments.

- CNEC Worley Parsons Engenharia, S.A. 2014b. EIA: AHE São Luiz do Tapajós; Estudo de Impacto Ambiental, Aproveitamento Hidrelétrico São Luiz do Tapajós. [EIA:São Luiz do Tapajós Dam. Environmental impact study: São Luiz do Tapajós hydroelectric dam (in Portuguese)] São Paulo, SP: CNEC (Consórcio Nacional dos Engenheiros Consultores). 25 Vols. + attachments. Retrieved, from http://licenciamento.ibama.gov.br/Hidreletricas/São%20Luiz%20do%20Tapajos/EIA_RIMA/.

- da Silva Neto, L.B. 2011. Ação Civil Pública 7786.39.2010.4.01.3603. 06 de dezembro de 2011 [Public Civil Suit 7786.39.2010.4.01.3603. December 6, 2011 (in Portuguese)] Sinop, MT: Juízo Federal da Vara Única de Sinop–MT.

- de Almeida, J. 2010. Alta Tensão na Floresta: Os Enawene e o Complexo Hidrelétrico Juruena [High voltage in the forest: The Enawene and the Juruena hydroelectric complex (in Portuguese)] Monograph, Cuiabá, MT: Curso de Especialização (Lato Sensu) em Indigenismo, Universidade Positivo, Operação Amazônia Nativa (OPAN). Retrieved, from http://amazonianativa.org.br/download.php?name=arqs/biblioteca/13_a.pdf&nome=Juliana%20de%20Almeida_Alta%20Tens%E3o%20na%20Floresta%20Os%20Enawene%20Nawe%20e%20o%20Complexo%20Hidrel%E9trico%20Juruena.pdf.

- Fanzeres, A. 2013. Povos indígenas da bacia do rio Juruena são preteridos de consulta prévia à emissão de licença em mais uma usina no rio do Sangue [Indigenous peoples of the Juruena River Basin are omitted from the prior consultation for licensing in yet another dam on the Sangue River (in Portuguese)]. Revista Sina. Retrieved June 18, 2013, from http://www.revistasina.com.br/portal/questao-indigena/item/9637-povos-ind%C3%ADgenas-da-bacia-do-rio-juruena-s%C3%A3o-preteridos-de-consulta-pr%C3%A9via-%C3%A0-emiss%C3%A3o-de-licen%C3%A7a-em-mais-uma-usina-no-rio-do-sangue.

- Fearnside PM. Social impacts of Brazil’s Tucuruí Dam. Environmental Management. 1999;24:483–495. doi: 10.1007/s002679900248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM. Soybean cultivation as a threat to the environment in Brazil. Environmental Conservation. 2001;28:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM. Avança Brasil: Environmental and social consequences of Brazil’s planned infrastructure in Amazonia. Environmental Management. 2002;30:748–763. doi: 10.1007/s00267-002-2788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM. Dams in the Amazon: Belo Monte and Brazil’s Hydroelectric Development of the Xingu River Basin. Environmental Management. 2006;38:16–27. doi: 10.1007/s00267-005-0113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside, P.M. 2012. Belo Monte Dam: A spearhead for Brazil’s dam building attack on Amazonia? GWF Discussion Paper 1210, 6 pp. Canberra: Global Water Forum. Retrieved, from http://www.globalwaterforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Belo-Monte-Dam-A-spearhead-for-Brazils-dam-building-attack-on-Amazonia_-GWF-1210.pdf.

- Fearnside PM. Carbon credit for hydroelectric dams as a source of greenhouse-gas emissions: The example of Brazil’s Teles Pires Dam. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 2013;18:691–699. doi: 10.1007/s11027-012-9382-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside, P.M. 2014a. Análisis de los Principales Proyectos Hidro-Energéticos en la Región Amazónica [Analysis of the principal hydro-energetic projects in the Amazon region (in Spanish)], 55 pp. Lima: Derecho, Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (DAR), Centro Latinoamericano de Ecología Social (CLAES), and Panel Internacional de Ambiente y Energia en la Amazonia. Retrieved, from http://www.dar.org.pe/archivos/publicacion/147_Proyecto_hidro-energeticos.pdf.

- Fearnside PM. Impacts of Brazil’s Madeira River dams: Unlearned lessons for hydroelectric development in Amazonia. Environmental Science & Policy. 2014;38:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2013.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM. Brazil’s Madeira River dams: A setback for environmental policy in Amazonian development. Water Alternatives. 2014;7:156–169. [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM, Barbosa RI. Political benefits as barriers to assessment of environmental costs in Brazil’s Amazonian development planning: The example of the Jatapu Dam in Roraima. Environmental Management. 1996;20:615–630. doi: 10.1007/BF01204135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnside PM, Pueyo S. Underestimating greenhouse-gas emissions from tropical dams. Nature Climate Change. 2012;2:382–384. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finer, M., and C.N. Jenkins. 2012. Proliferation of hydroelectric dams in the Andean Amazon and implications for Andes-Amazon connectivity. PLoS One 7: e35126 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035126. Retrieved, from http://www.plosone.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fiocruz (Fundação Oswaldo Cruz), and Fase (Federação dos Órgãos para Assistência Social e Educacional). 2013. Mapa de conflitos envolvendo injustiça, ambiente e saúde no Brasil [Map of conflicts involving environment, health and injustice in Brazil (in Portuguese)]. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Fiocruz. Retrieved, from http://www.conflitoambiental.icict.fiocruz.br/index.php?pag=ficha&cod=426.

- Freitas, T. 2014. Exportação de grãos vai dobrar, diz Bunge; para empresa, China manterá demanda [Exporting soy will double, says Bunge; the company believes China will maintain demand (in Portuguese)]. Folha de São Paulo, April 26, 2014, p. B-2.

- Garcia, R. 2014. Impacto do clima será mais amplo, porém mais incerto [Impact of climate will be broader but more uncertain (in Portuguese)]. Folha de São Paulo, March 31, 2014, p. C-5.

- Grupo de Trabalho Tapajós, and Ecology Brasil (Ecology and Environment do Brasil). 2014. Sumário Executivo: Avaliação Ambiental Integrada da Bacia do Tapajós. [Executive summary: Integrated environmental evaluation of the Tapajós Basin (in Portuguese)] 2580-00-AAI-RL-0001-01. Abril 2014. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Ecology Brasil. Retrieved, from http://www.grupodeestudostapajos.com.br/site/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Sumario_AAI.pdf.

- IHU (Instituto Humanitas Unisinos). 2012. Movimentos sociais repudiam Medida Provisória que diminui áreas protegidas na Amazônia [Social movements repudiate provisional measure that reduces protected areas in Amazonia (in Portuguese)] IHU Notícias. Retrieved May 31, 2012, from http://www.ihu.unisinos.br/noticias/510033-movimentos-sociais-e-organizacoes-da-sociedade-civil-lancam-carta-de-repudio-a-medida-provisoria-que-diminui-areas-protegidas-na-amazonia.

- Illescas, G. 2014. ¿Vecinos de Hidro Santa Rita firman acuerdo con la Empresa y el Gobierno? Centro de Médios Independentes (CMI-6) [Did the neighbors of the Santa Rita Dam sign an accord with the company and with the government? (in Spanish)]. Retrieved August 4, 2014, from http://cmiguate.org/vecinos-de-hidro-santa-rita-firman-acuerdo-con-la-empresa-y-el-gobierno/.

- ISA (Instituto Socioambiental). 2013. Dilma homologa terra indígena Kayabi (MT/PA) em meio a atritos por causa de hidrelétricas [Dilma gives final approval to the Kayabi Indigenous Land (MT/PA) in the midst of conflicts caused by dams (in Portuguese)] Notícias Direto do ISA, April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013 (17:11:09), from http://www.socioambiental.org/pt-br/noticias-socioambientais/dilma-homologa-terra-indigena-kayabi-mtpa-em-meio-a-atritos-por-causa-de.

- ISA (Instituto Socioambiental). 2014. Estado brasileiro é denunciado na OEA por ainda usar lei da ditadura militar [Brazil is denounced in the OAS for still using law from the military dictatorship (in Portuguese)]. Direto do ISA. Retrieved March 28, 2014, from http://www.socioambiental.org/pt-br/noticias-socioambientais/estado-brasileiro-e-denunciado-na-oea-por-ainda-usar-lei-da-ditadura-militar.

- Kahn JR, Freitas CE, Petrere M. False shades of green: The case of Brazilian Amazonian hydropower. Energies. 2014;7:6063–6082. doi: 10.3390/en7096063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kayabi, Apiaká, and Munduruku. 2011. Manifesto Kayabi, Apiaká e Munduruku contra os aproveitamentos hidrelétricos no Rio Teles Pires [Manifesto of the Kayabi, Apiaká and Munduruku against the hydroelectric dams on the Teles Pires River (in Portuguese)] Aldeia Kururuzinho Terra Indigena Kayabi, Alta Floresta, MT, Brazil. Retrieved, from http://www.internationalrivers.org/files/manifesto%20kayabi-mundurucu-apiaca-dez2011.pdf.

- Kayath, H.G. 2010. Processo N 33146-55.2010.4.01.3900. Decisão. Justiça Federal de 1ª Instância, Seção Judiciária do Pará [Case No. 33146-55.2010.4.01.3900 Decision. 1st Jurisdiction, Judicial Section of Pará (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved, from http://telmadmonteiro.blogspot.com.br/2010/12/liminar-suspende-o-processo-de.html.

- Kemenes A, Forsberg BR, Melack JM. Methane release below a tropical hydroelectric dam. Geophysical Research Letters. 2007;34:L12809. doi: 10.1029/2007GL029479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leino T, Lodenius M. Human hair mercury levels in Tucuruí area, state of Pará, Brazil. The Science of the Total Environment. 1995;175:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04908-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessa, F. 2012. Justiça manda parar obras de Teles Pires [Courts order halt to construction of Teles Pires Dam (in Portuguese)]. O Estado de São Paulo. Retrieved March 28, 2012, from http://www.estadao.com.br/noticias/impresso,justica-manda-parar-obras-de-teles-pires-,854290,0.htm.

- Lourenço, L. 2014. MPF processa União e Funai por demora na demarcação de terra indígena no Pará [Federal Public Ministry sues federal government and Funai for delay in demarcating indigenous land in Pará (in Portuguese)]. Agência Brasil. Retrieved May 27, 2014, from http://amazonia.org.br/2014/05/mpf-processa-uni%c3%a3o-e-funai-por-demora-na-demarca%c3%a7%c3%a3o-de-terra-ind%c3%adgena-no-par%c3%a1/.

- Macrologística. 2011. Projeto Norte Competitivo [Competitive North Project (in Portuguese)]. São Paulo, SP: Macrologística Consultaria. Retrieved, from http://www.macrologistica.com.br/images/stories/palestras/Projeto%20Norte%20Competitivo%20-%20Apresentação%20Executiva%20no%20Ministério%20do%20Planejamento%20-%20Agosto%202011.pdf.

- McCully, P. 2001. Silenced rivers: The ecology and politics of large dams: Enlarged and updated edition, 359 pp. New York, NY: Zed Books.

- Menezes, O. 2012a. Suspensão de liminar ou antecipação de tutela N. OO18625-97.2012.4.01.0000/MT. Decisão. 09 de abril de 2012 [Suspension of provisional order or anticipation of guardianship No. OO18625-97.2012.4.01.0000/MT. Decision. April 9, 2012 (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved, from http://www.prpa.mpf.mp.br/news/2014/arquivos/Suspensao_Liminar.pdf/at_download/file.

- Menezes, O. 2012b. Suspensão de liminar ou antecipação de tutela N. 0075621-52.2011.4.01.0000/MT Decisão. 16 de janeiro de 2012 [Suspension of provisional order or anticipation of guardianship No. 0075621-52.2011.4.01.0000/MT Decision. January 16, 2012 (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved, from http://www.prpa.mpf.mp.br/news/2014/arquivos/Suspensao%20de%20Seguranca.doc/at_download/file.

- Mermet, L. 2011. Strategic environmental management analysis: Addressing the blind spots of collaborative approaches, 30 pp. Paris: Institut du Développement Durable et des Relations Internationales (IDDRI). Retrieved, from http://www.iddri.org/Publications/Strategic-Environmental-Management-Analysis-Addressing-the-Blind-Spots-of-Collaborative-Approaches.

- Millikan, B. 2011. Dams and hidrovias in the Tapajos Basin of Brazilian Amazonia: Dilemmas and challenges for Netherlands–Brazil relations. International Rivers Technical Report, International Rivers, Berkeley, CA. Retrieved, from http://www.bothends.org/uploaded_files/inlineitem/41110615_Int_Rivers_report_Tapajos.pdf.

- Millikan, B. 2012. Comments to PJRCES on the Teles Pires Hydropower Project (Brazil). Retrieved, from http://www.internationalrivers.org/node/7188.

- Monteiro, T. 2011. Três hidrelétricas ameaçam indígenas no rio Teles Pires [Three hydroelectric dams threaten indigenous people on the Teles Pires River (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved August 22, 2011, from http://telmadmonteiro.blogspot.com.br/2011/08/tres-hidreletricas-ameacam-indigenas-no.html.

- Monteiro, T. 2013a. Hidrelétrica São Manoel: Cronologia de mais um desastre—Parte I. [São Manoel Hydroelectric Dam: Chronology of one more disaster—Part 1 (in Portuguese)]. Correio da Cidadania, August 15, 2013, from http://www.correiocidadania.com.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=8728:submanchete150813&catid=32:meio-ambiente&Itemid=68.

- Monteiro, T. 2013b. Hidrelétrica São Manoel: Cronologia de mais um desastre—Parte II [São Manoel Hydroelectric Dam: Chronology of one more disaster—Part II (in Portuguese)]. Correio da Cidadania. Retrieved August 19, 2013, from http://www.correiocidadania.com.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=8746:submanchete190813&catid=75:telma-monteiro&Itemid=192.

- Moreira, P.F. (ed.). 2012. Setor Elétrico Brasileiro e a Sustentabilidade no Século 21: Oportunidades e Desafios, 2a ed. [The Brazilian electrical sector and sustainability in the 21st century, 2nd. Edn. (In Portuguese)], 100 pp. Brasília, DF: Rios Internacionais. Retrieved, from http://www.internationalrivers.org/node/7525.

- MPF/PA (Ministério Público Federal no Pará). 2011. MPF/PA: Justiça paralisa usinas de Colíder, Sinop e Magessi, no Teles Pires [Federal Public Ministry in Pará: Courts halt Colíder, Sinop and Magessi Dams on the Teles Pires River (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved, from http://mpf.jusbrasil.com.br/noticias/2957565/mpf-pa-justica-paralisa-usinas-de-colider-sinop-e-magessi-no-teles-pires.

- MPF/PA (Ministério Público Federal no Pará). 2012. MP pede suspensão do licenciamento e obras da usina de Teles Pires por falta de consulta a indígenas [Public Ministry requests suspension of licensing construction of the Teles Pires Dam due to lack of consultation with indigenous peoples (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved March 19, 2012, from http://www.prpa.mpf.gov.br/news/2012/mp-pede-suspensao-do-licenciamento-e-obras-da-usina-de-teles-pires-por-falta-de-consulta-a-indigenas.

- Oliver-Smith, A. (ed.). 2009. Development and dispossession: The crisis of development forced displacement and resettlement, 344 pp. London: SAR Press.

- Oliver-Smith A. Defying Displacement: Grassroots Resistance and the Critique of Development. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2010. p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, F. 2013. Índios Munduruku vão à Brasília contra usinas no Tapajós [Munduruku Indians go to Brasília against dams on the Tapajós (in Portuguese)]. OEco. Retrieved December 12, 2013, from http://www.oeco.org.br/noticias/27850-indios-munduruku-vao-a-brasilia-contra-usinas-no-tapajos.

- Ostrom E. Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. The Policy Studies Journal. 2011;39:7–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00394.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmquist, H. 2014. Usina Teles Pires: Justiça ordena parar e governo federal libera operação, com base em suspensão de segurança. Ponte. Retrieved November 27, 2014, from http://ponte.org/usina-teles-pires-justica-ordena-parar-e-governo-federal-libera-operacao-com-base-em-suspensao-de-seguranca/.

- Presser, I. 2014. Processo N° 0017643-16.2013.4.01.3600—1ª Vara Federal Nº de registro e-CVD 00029.2014.00013600.2.00569/00033 [Case No. 0017643-16.2013.4.01.3600—1st Federal Judgeship Registry No. e-CVD 00029.2014.00013600.2.00569/00033 (in Portuguese)]. Cuiabá, MT: Tribunal Regional Federal da Primeira Região. Retrieved April 28, 2014, from http://www.prpa.mpf.mp.br/news/2014/arquivos/liminar.isolados.pdf.

- Prudente, A.S. 2013. O terror jurídico-ditatorial da suspensão de segurança e a proibição do retrocesso no estado democrático de direito [Judicial-dictatorial terror—security suspension and the prohibition of delays in the democratic state of law (in Portuguese)]. Revista Magister de Direito Civil e Processual Civil 10: 108–120. Retrieved, from http://www.icjp.pt/sites/default/files/papers/o_terror_juridico_completo.pdf.

- Prudente, A.S. 2014. A suspensão de segurança como instrumento agressor dos tratados internacionais [The security suspension as an instrument of aggression against international treaties (in Portuguese)]. Revista Justiça e Cidadania, No. 165. Retrieved, from http://www.editorajc.com.br/2014/05/suspensao-seguranca-instrumento-agressor-tratados-internacionais/.

- Ross, K. 2012. Community leader and defender of the Sogamoso River disappears. International Rivers. Retrieved November 12, 2012, from http://www.internationalrivers.org/blogs/259/community-leader-and-defender-of-the-sogamoso-river-disappears.

- Santos, S.M.S.B.M., and F.M. Hernandez (ed.). 2009. Painel de Especialistas: Análise Crítica do Estudo de Impacto Ambiental do Aproveitamento Hidrelétrico de Belo Monte, 230 pp. Belém, Pará: Painel de Especialistas sobre a Hidrelétrica de Belo Monte. Retrieved, from http://www.xinguvivo.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Belo_Monte_Painel_especialistas_EIA.pdf.

- Scudder, T. 2006. The future of large dams: Dealing with social, environmental, institutional and political costs, 408 pp. London, UK: Routledge.

- TRF-1 (Tribunal Regional Federal da 1ª Região). 2013. TRF determina a suspensão das obras da UHE Teles Pires até a realização do Estudo do Componente Indígena. Processo n.º 058918120124013600, Data do julgamento: 09/10/13. [Federal Regional Court orders suspension of construction of the Teles Pires Dam until a Study of the Indigenous Component is carried out. Case No. 058918120124013600, Date of judgement: October 9, 2013 (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved, from http://trf-1.jusbrasil.com.br/noticias/112010609/trf-determina-a-suspensao-das-obras-da-uhe-teles-pires-ate-a-realizacao-do-estudo-do-componente-indigena.

- TRF-1 (Tribunal Regional Federal da 1ª Região). 2014. Consulta Processual/MT 0013839-40.2013.4.01.3600 [Consultation of legal case/MT 0013839-40.2013.4.01.3600 (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved, from http://processual.trf1.jus.br/consultaProcessual/index.php?secao=MT.

- Tundisi JG, Goldemberg J, Matsumura-Tundisi T, Saraivad ACF. How many more dams in the Amazon? Energy Policy. 2014;74:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2014.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Val, A.L., V.M.F. deAlmeida-Val, P.M. Fearnside, G.M. dos Santos, M.T.F. Piedade, W. Junk, S.R. Nozawa, S.T. da Silva, and F.A.C. Dantas. 2010. Amazônia: Recursos hídricos e sustentabilidade [Amazonia: Water resources and sustainability (in Portuguese)]. In Aguas do Brasil: Análises Estratégias, [Waters of Brazil: Strategic analyses (in Portuguese)], ed. C.E.M. Bicudo, J.G. Tundisi, and M.C.B. Scheuenstuhl, 95–109, 222 pp. São Paulo, SP: Instituto de Botânica.

- WCD (World Commission on Dams). 2000. Dams and development—A new framework for decision making—the report of World Commission on Dams. WCD and Earthscan, London, 404 pp.

- WWF Brasil. 2012. Construção de hidrelétricas ameaça rio Tapajós. [Construction of hydroelectric dams threatens the Tapajós River (in Portuguese)]. Retrieved February 11, 2012, from http://www.wwf.org.br/informacoes/sala_de_imprensa/?30562/construo-de-hidreltricas-ameaa-rio-tapajs.

- WWF Brasil. 2014. Hidrelétricas podem alagar parque nacional na Amazônia [Hydroelectric dams could flood national park in Amazonia (in Portuguese)]. Amazônia. Retrieved June 5, 2014, from http://amazonia.org.br/2014/06/hidrel%c3%a9tricas-podem-alagar-parque-nacional-na-amaz%c3%b4nia/.

- Yan, K. 2013. World water day marked by death of indigenous anti-dam protester. International Rivers. Retrieved April 4, 2013, from http://www.internationalrivers.org/blogs/246/world-water-day-marked-by-death-of-indigenous-anti-dam-protester.