Abstract

The south Indian State of Karnataka, once part of several kingdoms and princely states of repute in the Deccan peninsula, is rich in its historic, cultural and anthropological heritage. The State is the home to 42,48,987 tribal people, of whom 50,870 belong to the primitive group. Although these people represent only 6.95 per cent of the population of the State, there are as many as 50 different tribes notified by the Government of India, living in Karnataka, of which 14 tribes including two primitive ones, are primarily natives of this State. Extreme poverty and neglect over generations have left them in poor state of health and nutrition. Unfortunately, despite efforts from the Government and non-Governmental organizations alike, literature that is available to assess the state of health of these tribes of the region remains scanty. It is however, interesting to note that most of these tribes who had been original natives of the forests of the Western Ghats have been privy to an enormous amount of knowledge about various medicinal plants and their use in traditional/folklore medicine and these practices have been the subject matter of various scientific studies. This article is an attempt to list and map the various tribes of the State of Karnataka and review the studies carried out on the health of these ethnic groups, and the information obtained about the traditional health practices from these people.

Keywords: Ethnic people, health, Karnataka, scheduled tribe, traditional/herbal medicine, tribe

Introduction

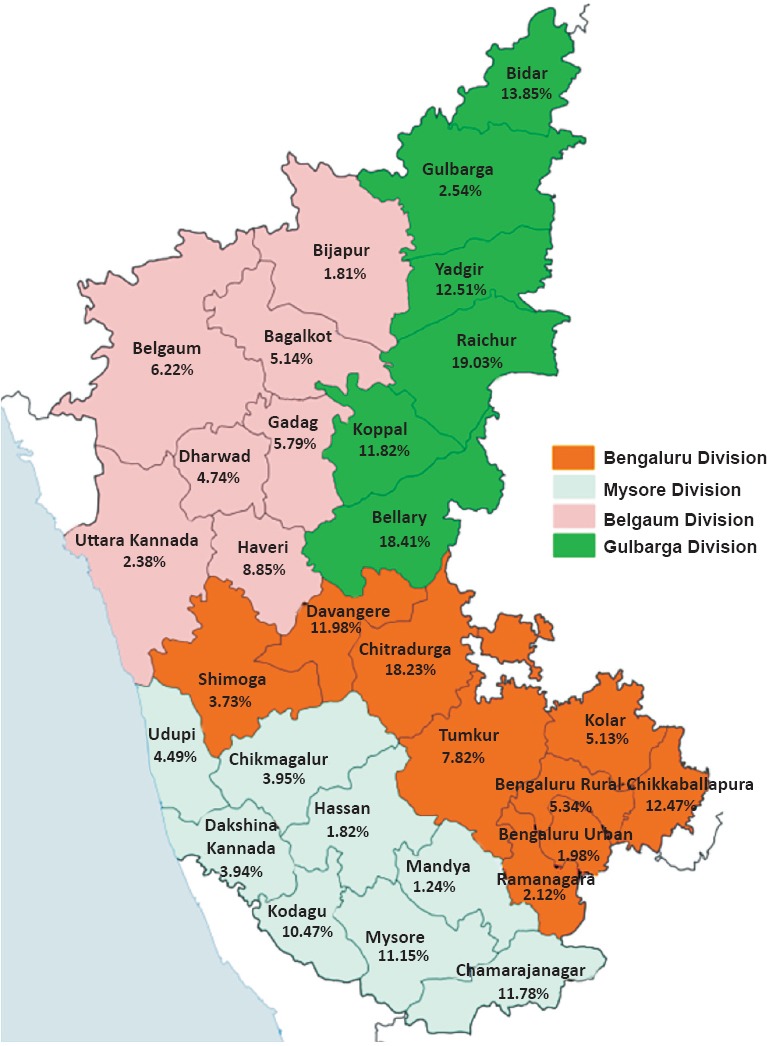

The State of Karnataka was created on November 1, 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act. Originally known as the State of Mysore, it was renamed as Karnataka in 19731 with Bangalore (now Bengaluru), the largest city in the State as its capital. Karnataka is bordered by the Arabian Sea and the Lakshadweep Sea to the West, Goa to the North-West, Maharashtra to the North, Telangana to the North-East, Andhra Pradesh to the East, Tamil Nadu to the South-East, and Kerala to the South-West. With an area of 1,91,976 square kilometres (74,122 sq miles), or 5.83 per cent of the total geographical area of India, it is the seventh largest State by size. It ranks eighth in terms of the number of inhabitants which stands at 61,130,704 according to the 2011 census2. The State comprises 30 districts (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map of Karnataka showing tribal population as percentage of total population in each of its 30 districts. Souce: Ref. 2.

Kannada is the most widely spoken and official language of the State. Apart from Kannadigas, Karnataka is the home to Tuluvas, Kodavas and Konkanis along with minor populations of Tibetan Buddhists. Although there are other ethnic tribes, the Scheduled Tribe population comprises some of the better known tribes like the Soligas, Yeravas, Todas and Siddhis and constitute 6.95 per cent of the total population of Karnataka2.

Currently there are 50 Scheduled Tribes (ST) in Karnataka notified according to the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order (Amendment) Act 20032. The names of these tribes, along with their population in the State and districts mostly inhabited by them are listed in the Table. As many as 14 of these tribes are either exclusively found in Karnataka or are predominant inhabitants of the State.

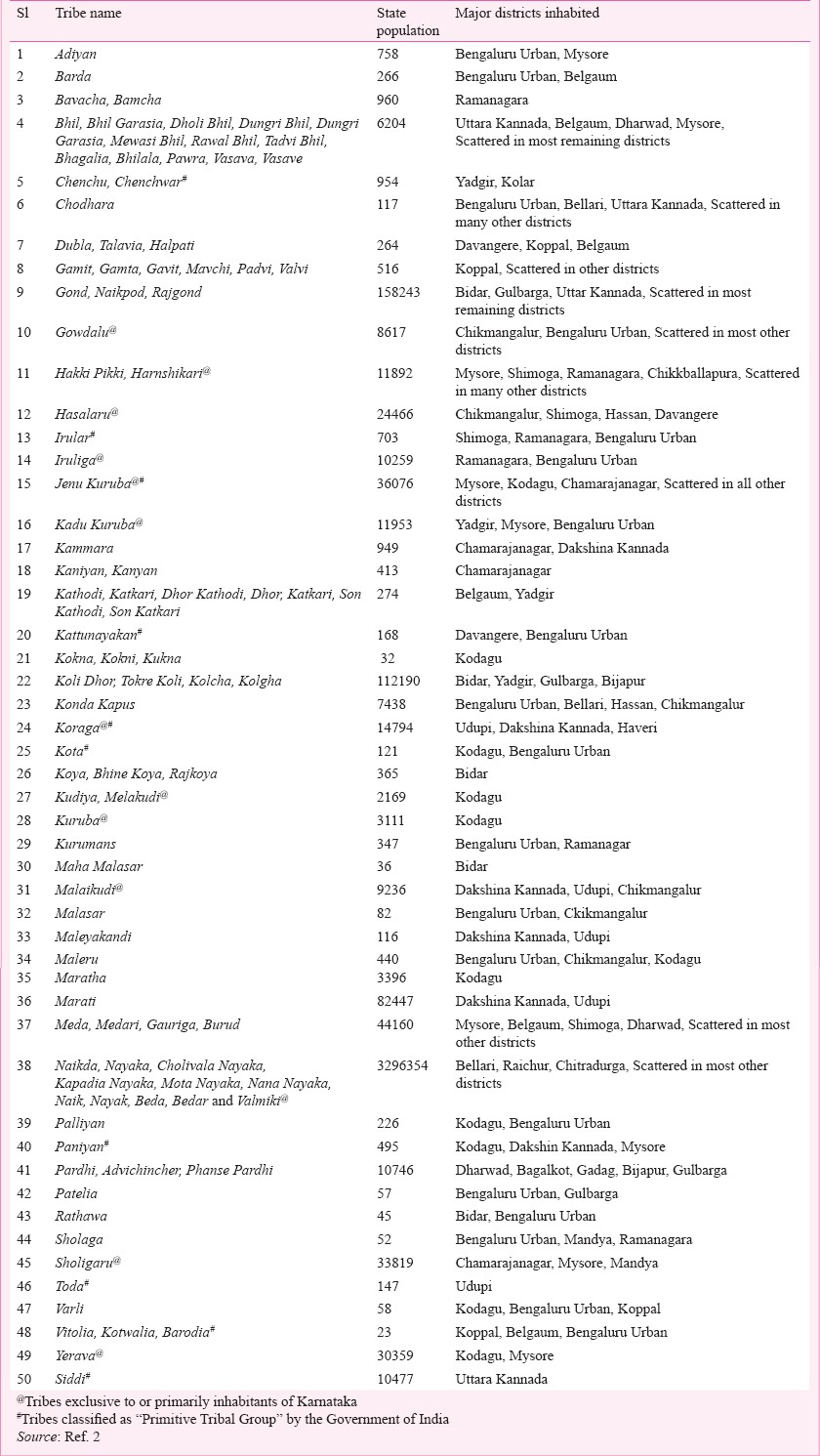

Table.

List of Scheduled Tribes of Karnataka along with their population and most inhabited districts

The tribes of Karnataka

Members of the Adiyan tribe live mostly in Mysore and districts bordering Kerala and speak Kannada. They are only 758 in number and are mostly agricultural labourers. They remain poor and have a low literacy rate. Marriages among cousins are common. There are a few members (266) of the Barda tribe of Gujarat and Maharashtra found in the State, mostly in the northern districts. They speak Barda language which is similar to Marathi and Gujarati. They are agricultural labourers, and are mostly endogamous. The Bavacha/Bamcha are Hindu tribes who speak the Bavchi dialect3. They are 960 in number and are mostly inhabitants of Ramanagar district.

Bhils are adivasis of Central Indian origin. The Bhil tribes are divided into a number of endogamous territorial divisions, which in turn have a number of clans and lineages. Most Bhils now speak the language of the region they reside in. Originally hunters and soldiers, they are mostly agricultural workers with hunting and gathering remaining a significant subsidiary occupation3,4. The Bhil population in Karnataka is 6,204 and are scattered in most districts of the State, more so in Uttara Kannada and Belgaum districts4.

The Chenchus are an aboriginal tribe who speak the Chenchu or Chenchwar language, a branch of Telugu, and live mostly in the forests of Andhra Pradesh. About 954 of them inhabit bordering districts of Karnataka like Yadgir and Kolar. The Chenchus are one of the original primitive tribal groups that are still dependent on forests and do not cultivate land but hunt for a living. Some however, live symbiotically with non-tribal communities and many collect forest products for sale to non-tribal people. The Chodharas are a group of about 117 people living in Karnataka among the 20,000 odd members most of whom inhabit Gujarat and Maharashtra. They are related to the Rajputs and speak Chodri. Most of the Chodhari people work as small farmers growing cotton, vegetables, and rice.

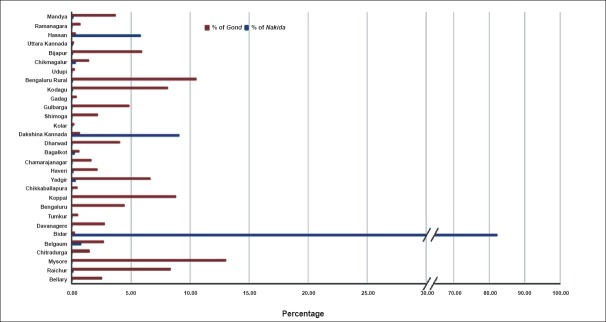

The Dublas, some of whom are also called Talavia or Halpati, are Hindu tribes originating from the Rajputs in Gujarat and Maharashtra. Dubla society consists of several endogamous sub-divisions with agriculture as primary occupation4. They are also very few in number (264) and are mostly scattered in distribution over the State. The Gamit tribe (also known as Gamit, Gavit, Mavchi and Pandvi) people speak in Gamit. They are about 516 of them who are now inhabitants of Karnataka, mostly found in Koppal and scattered over several other districts. The Gond tribe is the largest of Dravidian people of central India, spread over various States including the North-Western districts of Karnataka (Fig. 2). They are the second largest tribal group found in the State. Gondi language is related to Telugu and other Dravidian languages. Gowdalu are 8,617 in number according to the 2011 Census data2, and speak Gowdalu language. They are mostly found in Chikmangalur and Bengaluru Urban districts in the State. The Hakki-Pikki clan is a semi-nomadic group and they live near Bidadi in Karnataka. Their population in the State is 11,892 as per 2011 Census2. The tribe has taken up hunting as their occupation but many are now showing more interest in agriculture and floral decoration. The Hasalaru are Hindu tribes of Karnataka. They are 24,466 in number and speak Tulu and concentrated in several districts including Chikkamangaluru, Shimoga, Udupi, and Davangere. In Karnataka, people belonging to Irular tribe are about 700 in number. They are more conspicuous in the Nilgiri Hills of neighbouring Tamil Nadu and Kerala and are listed under the Primitive Tribe Group. They are Hindus and speak Irula which is related to the Dravidian languages Tamil and Kannada. These people are descendants of gypsies living in caves with hunting and gathering as their ancestral occupation. They subsequently learnt the art of cultivation. People from the same clan within the Irular tribe do not intermarry. Their literacy rate is very low at 36.27 per cent5. The Iruliga are also primarily tribes of Karnataka with a total population of about 10,259, mostly living in Ramanagar and Bengaluru Urban districts. They are Hindus and while Kannada is their principal language, a few other languages are also spoken.

Fig. 2.

Bar diagram showing distribution of the largest two tribes in Karnataka, the Gond and Naikda or Nayaka in the 30 districts of the State (Generated from Census data, 2011). Source: Ref. 2.

The population of Jenu Kurubas is 36,076 in Karnataka2 mostly living in the districts of Mysore, Kodagu, and Chamarajanagar. A few are also found outside the State mostly in the border forests of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Also known by the names ‘Then Kurumba’ or ‘Kattu Naikar’, they are members of the primitive tribal group and are now mostly occupied as daily labourers for landlords in plantations in the region. They have a close-knit community and rarely mingle with other neighbouring tribal communities. The literacy rate is 47.66 per cent5. The Kadu Kurubas are the original inhabitants of the forests of Nagarahole and Kakanakote in the Western Ghats of Karnataka. Kadu Kurubas are about 11,953 in number, mostly living in Mysore, Kodagu, Chamarajanagar, and other districts of Karanataka and the remaining in the forests of Tamil Nadu. They are primarily Hindus, speaking Kannada language. The Kammara live in Dakshina Kannada district and Kollegal taluk of Chamarajnagar district of Karnataka. They speak local language and are 949 in number and the majority of these tribe are scattered in Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, and Chattisgarh. They are blacksmiths, carpenters and also involved in cultivation. The Kaniyan is a tribe from Kerala found mostly in Kollegal taluk of Chamarajanagar district of the State. Only 413 in number reside in the district. These people speak local language although the majority of these tribes speak Malayalam. The members of this tribe are mostly Hindus. Among the approximate 3,00,000 members of the Katkari and Marathi-Konkani speaking Kathodi or Katkari tribe, only a few (275) live scattered in the State of Karnataka. The Kathodi are recognized as the primitive tribal group by the Government of India in the State of Gujarat.

About 168 members of Kattunayakan tribe which total around 70,000 mostly inhabiting Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Pondicherry, are scattered in various districts of Karnataka. This tribe is regarded as a primitive tribe in Kerala. An extremely small number (32) of the Kokna tribe are scattered over several districts of Karnataka. They are mostly Hindu by religion. Their primary language is Kukna perhaps derived from Konkani. Karnataka State has the third largest share (1,12,190) of the Koli Dhor tribe. They are scattered in the North and North-West parts of the State including Bidar, Yadgir, Gulbarga and Bijapur. About 7,438 members of the Konda Kapu tribe live in the districts of Karnataka, mostly adjoining Andhra Pradesh. The Koraga tribe is among the two primitive and most backward tribes declared by the Government of India5. This is not only one of the most notable tribes of Karnataka, but also one of the primitive tribal group. This tribe is scattered over many districts of the State, particularly in Udupi and Dakshina Kannada. They are also found in Haveri and in small numbers in Shimoga, Uttara Kannada and Kodagu districts. Their number is 14,794 as per the 2011 Census2.

Koragas spend most of their income on alcohol, which is consumed by all ages, and also indulge in smoking beedi and chewing betel. They subsist mainly on rice and meats such as pork and beef, although they are increasingly also using produce such as pulses and vegetables. Diet is poor and malnutrition is common in children6. Education level is low. The Kota tribe is a small group of ethnic people indigenous to the Nilgiri Hills of Tamil Nadu and are recognized as primitive tribal group. They are about 1500 in number7, of which about 121 are in Karnataka State2. They have been subject to good amount of anthropological, linguistic and genetic analysis. In Karnataka State, particularly in the Bidar district, there are only about 365 members of the Koya tribe which is a very large tribe in neighbouring Andhra Pradesh. The Kudiya tribe mainly belonging to the State of Karnataka, and 2,169 of individuals of this tribe live in the State, mostly in Kodagu district. The Kuruba inhabit the thickly forested slopes and foothills of the Nilgiri plateau in Kodagu district of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu States. Their population in Katnataka is 3,1112. The Kuruman tribe of Karnataka is represented by only 347 individuals of this ethnic group who are mostly located in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. They speak southern Kannada language. Maha Malasar is a very small group of ethnic tribe living in Annamalai Hills in south India. Karnataka has about 36 of these people while Tamil Nadu and Kerala house most of them. Malaikudi is also a Karnataka ethnic group with about 9,236 people belonging to this tribe inhabiting the Sahyadri hill ranges of Dakshin Kannada, Udupi and Chikmagalur districts of Karnataka. The Malaikudi tribe speak a dialect of the Dravidian language, Tulu. Tulu and Kannada are spoken by them for inter-group communication. The Malasar tribe has about 9100 ethnic people in the States of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, of whom about 84 inhabit Chikmagalur district of Karnataka. They speak a mixture of the Malayam and Tamil languages. The Malayekandi tribe has also been listed separately as Malaikudi and Maleru. There are 116 of the approximate 2,000 people7 of these tribes in Karnataka. Apart from Chikmagalur district, these tribes are scattered over Koppal, Raichur and Gulbarga districts. The Maleru tribe is about 440 in number and is almost exclusive to Karnataka State. They mostly inhabit Chikmagalur, Shimoga, Davangere, Dakshin Kanada, Udupi, Hassan, and Kodagu districts. The Maratha of Kodagu and Marati of Dakshina Kannada are groups that have received tribal status only in these districts of Karnataka. According to the 2011 census2, there are 3,396 Maratha people in Kodagu district while there are 82,447 Marati people in Dakshin Kannada. These communities speak Marathi among themselves and in Tulu and Kannada with others. They are normally vegetarians.

In Karnataka, there are two communities with the name Meda; one of these is restricted to the district of Kodagu. They speak Kodagu, a Dravidian language. In other parts of Karnataka, there is another community of basket-makers known as Meadar of Meda. The Meda community is almost exclusively present in Karnataka with a population of about 44,160 scattered throughout all the districts. Nayaka, tribe as the name implies ‘a leader’ is mostly non-vegetarian. Nayaka, popularly known by Palegar, Beda, Valmiki, and Ramoshi Parivara are found all over the State but they are concentrated in the Chitradurga, Shimoga, Bellary and Tumkur districts. Their population is 32,96,354. The Paliyan, or Palaiyar or Pazhaiyarare are a group of more than 10,000 Adivasi Dravidian people living in the south Western Ghats mountaneous rain forests in south India, especially in Tamil Nadu and Kerala7. They belong to the primitive tribal group. About 226 of them inhabit the southern tip of the State of Karnataka especially in Kodagu district. Most people of this tribe are traders of forest products, food cultivators and beekeepers. About 495 people of the Paniyan tribe reside in Karnataka mainly in the southern districts Kodagu, Dakshin Kannada and Mysore. The Pardhis are migrant people, scattered over a wide area of central India in the States of Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka. In Karnataka, their population is about 10,746 and are mostly found in the districts of Dharwad, Bagalkot, Gadag, Bijapur and Gulbarga. Their language, Pardhi, is one of the Bhil languages. Among the western Indian Patelia tribe, only 57 inhabit Karnataka, most of them in Bidar district alone. The Rathwas derived their name from the word ‘rathbistar’, which means inhabitant of a forest or hilly region. They are a moderately large tribe but very few (45 individuals) inhabit Karnataka State. Only a few are located in Bengaluru Urban and Bidar districts. They are endogamous, and consist of a number of exogamous clans. They are at present mostly small and medium sized farmers. The Soliga/Sholiga and Sholigaru/Soligaru tribes inhabit the Biligirirangan (BR) Hills and associated ranges in southern Karnataka, mostly in the Chamarajanagar and Erode districts of Tamil Nadu. Many are also concentrated in and around the BR Hills in Yelandur and Kollegal taluks of Chamarajanagar District. They use the title Gowda, which means a headman. In Karnataka, they are mainly distributed in the hilly parts of Mysore district, Ramanagar, and Mandya. This area is covered with forests, and experiences low humidity and heavy rainfall. They are normally vegetarians, and eat mainly tubers. Toda tribe is one of the most ancient and peculiar tribes of Nilgiri Hills of Tamil Nadu. There are only a few (157) of them in Karnataka in the district of Udupi. The Todas have their own language and own secretive customs and regulations. The Varlis/Warlis are Adivasis, living in mountainous as well as coastal areas of Maharashtra-Gujarat border and surrounding areas. There are only 58 of them in Karnataka, mostly in Kodagu and Koppal districts. Vitolia is an extremely small group of 23 people living scattered over many districts including Koppal, Belgaum, and Bengaluru. They are believed to the descendents from the Gambit tribe and were regarded as untouchables. Vitolia is included the primitive tribal group by the Government of Gujarat where they are found most. A few might have migrated to Karnataka from south Gujarat and Maharashtra earlier. Their literacy rate is 43.8 per cent. A few centuries ago the Yerava/Ravula was a thriving, agriculture and forest-based tribe, in Wayanad and Kodagu districts of Kerala and Karnataka, respectively. The population as per 2011 census2 is 30,359 in Karnataka and found mostly in Kodagu and Mysore districts. The Siddis tribe of Karnataka is an ethnic group. There is a 50,000 strong Siddi population across India, of which about 10,477 are loacated around Yellapur, Haliyal, Ankola, Joida, Mundgod and Sirsi taluks of Uttara Kannada district and in Khanapur of Belgaum district and Kalghatgi of Dharwad district.

Demography

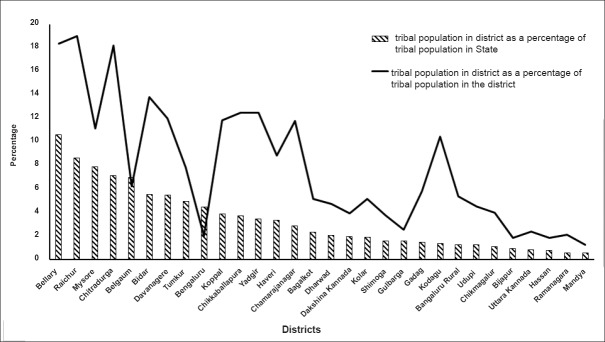

The total number of tribal people recognized by the Government in Karnataka is about 42,48,978 which is 6.95 per cent of the total population of the State. There has been a 6 per cent increase in the tribal population during the last decade. It was 6.6 per cent of the State population in 2001 with the absolute number of 34,63,9862,8. Bellary has the highest population (10.6%) of Scheduled Tribes (ST) as a percentage of the ST population in the State. Raichur (8.6%) has the second highest percentage of ST population followed by Mysore (7.8%) Chitradurga (7.1%) and Belgaum (6.9%) (Fig. 3). Bellary (4,51.406), Raichur (3,67,071), Mysore (3,34,547) and Chitradurga (3,02,554) are also the districts where the maximum number of tribals reside. Raichur has the highest population of the STs as a percentage of the total population of the district (19.03%), followed by Bellary (18.41%) and Chitradurga (18.23%) districts. The ST population of Karnataka is primarily rural (84.7%). Among major STs, Koli Dhor have the highest (92.2%) rural population, followed by Gond (91.7%), Marati (90.8%) and Naikda (85.1%). District-wise distribution of ST population shows that the tribal population is present in all 30 districts of the State. However, most of these ethnic groups are mainly concentrated in the districts of Bellary, Raichur, Mysore, Chitradurga, Belgaum, Davanagere and Tumkur. These seven districts account for 52 per cent of the ST population of the State. The remaining 48 per cent of the ST population are distributed in the other 23 districts9,10.

Fig. 3.

Diagram showing tribal populations of individual districts as a percentage of the total population of the district and as a percentage of the tribal population of the Karnataka State (Generated from Census data 2011). Source: Ref. 2.

Sex ratio

The sex ratio for Scheduled Tribes in Karnataka is 990 females per 1000 males which is higher than the all-India average of 964 for STs as well as the State overall average of 973 females per 1000 male population2. The sex ratios of ST population in rural and urban areas of Karnataka are 990 and 993 females per 1000 males, respectively which increased from 975 and 960, respectively in 200111. There has been a perceptible improvement in the sex ratio of STs since 1991 when it was only 961 females per 1000 males11.

Literacy rate

The literacy rate of STs in Karnataka is a cause for concern, as it has consistently been lower than that of the total population. The literacy rate among the tribes, which was 36.0 per cent in 1991, increased to 48.3 per cent in 2001 and further increased to 53.9 per cent in 2011, while the State average moved up from 66.64 to 75 per cent in last decade2,11. The literacy rate among the tribal population in Karnataka is 51 per cent in urban and 65.7 per cent in rural areas, while the overall figure of the State is 60.4 per cent in rural areas and 76.2 per cent in urban areas. The literacy rate among male population was found to be significantly higher at 57.5 per cent than the female counterparts where it is 42.5 per cent2.

Among the major STs, the Toda are reported to have the highest (78.9%) literacy rate, followed by Malayekandi (78.45%), Maleru (74.77%), Maratha (74.09%), and Patelia (73.68%) tribes. The female literacy rate of 42.5 per cent among tribal population according to 2011 census2 has shown marginal increase from 41.72 per cent in 2001 but is slightly lower than the general female population in the State (44.62%).

Health status of the tribes

The health needs and problems of any community are influenced by interaction of various socio-economic and political factors. There are a number of studies on the tribes, their culture and the impact of acculturation on the tribal society12.

With the view to provide the essential primary health care to the tribal population, opening of Primary Health Centres (PHCs) in tribal dominant districts was an integral part of various tribal development programmes implemented in the country since 194713. Unresponsive auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs), inconvenient opening times and little or no community participation are some of the problems plaguing the PHCs in tribal areas over the years14. In addition, the lack of accountability has led to absentee doctors, and it has always been a challenge to get quality doctors into tribal areas. Despite these odds, Karnataka, at present, has functional PHCs that cover a rural population of about 20,000 in the hilly and tribal areas and Subcentres that cover another 3,00014. Despite efforts from the Government and non-Government organizations to take primary health care to these marginalized people, there has been a very limited number of studies reported on the health status of the tribal communities of the State. Studies had been extremely limited to only a handful of tribes like the Jenu Kuruba, Koraga, Iruliga, Hakki-Pakki and Siddis. With only a few reports available on the prevalence of various communicable and non-communicable diseases in these tribal communities, it is difficult for the Government to devise strategies to combat these health problems. Existing literature ranges from studies on tracing the genetic origin and relatedness of some of the tribes to the assessment of availability of health care facility and their utilization, and to study of anaemia and hypertension among the tribes, their nutritional status, lifestyle disorders, and oral hygiene. Almost nothing is reported about the status of communicable diseases in these populations. A summary of the existing information on the health status and health research carried out on the tribal people of Karnataka is provided here.

Genetic studies

A genome wide study was carried out using autosomal markers to survey and understand the population history of the Siddis15. This study showed their link with Africans, Indians and Europeans (Portuguese), confirming the belief about their origin. The genetic affinity of the three tribes, Jenu Kuruba, Betta Kuruba and Soliga tribes of southern Karnataka was studied using ten polymorphic genetic markers16. The authors concluded that the Jenu Kuruba and Soliga tribe who exhibited less inter-group genetic distance, clustered together, whereas Betta Kuruba who possessed comparatively higher genetic distance with the former populations fell out of the cluster. However, these three tribes showed a low genetic distance suggesting a recent divergence or low degree of genetic isolation.

Availability and utilization of health care

A study was carried out among the Koraga tribes in Dakshina Kannada district to assess the availability and accessibility of basic facilities and to determine the utilization of health care facilities by them17. The study showed an overall literacy level among Koragas for both the sexes to be 70.5 per cent which was higher than the State level literacy rate for STs. The study further revealed that poverty among Koraga families was a problem. The study stressed on scaling up of efforts to improve their housing, sanitation, literacy and employment conditions which ultimately contribute to improvement of quality of life.

Nutritional status

Practices such as late initiation of breastfeeding, no feeding of colostrum, and faulty weaning practices, are of particular concern, in the tribal areas due to certain adverse conditions like lack of access to health services, illiteracy, unhygienic personal habits, etc18. A study was carried out to understand the breastfeeding practices among the Hakki-Pikkis, a tribal population of Mysore district19. The study revealed that about 76 per cent of the study population breastfed their children immediately after birth while 20 per cent of the mothers initiated breastfeeding on the second day, and 4 per cent on third day of the birth of the child. Those 24 per cent of the mothers who did not feed colostrum at birth considered colostrum as thick, cheesy, indigestible, unhygienic and not good for the infant, in tune with their traditional belief. The study highlighted the need for conduct of various awareness programmes on feeding education to mothers belonging to these tribal communities and to mitigate various myths about breastfeeding. The authors concluded that the poor infant and child feeding practices might be linked to high rate of illiteracy and poor socio-economic condition. This study highlighted the importance of intense literacy campaign, income generating activities and health education by health personnel among these tribes19.

Keeping in view that malnutrition is one of the major public health problems in many countries affecting more than 30 per cent of children under 5 yr of age, and more so in tribal communities19,20,21, a community based study on nutritional status of the Jenu Kuruba tribes of Mysore district was carried out among 220 children aged between 1-5 yr22. The overall prevalence rates of underweight, stunting and wasting were found to be 38.6, 36.8 and 18.6 per cent, respectively. The study showed that prevalence of underweight increased with increase in age of the child in this community. It also linked malnutrition with unfavourable socio-demographic factors. Overall prevalence rates of underweight, stunting and wasting have been reported to be 54.5, 54 and 27.6 per cent, respectively among the ST population of the entire country as per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 323. In comparison, the total prevalence rates of underweight, stunting and wasting in Karnataka were 33.3, 42.4 and 18.9 per cent, respectively23.

A community based cross-sectional study was conducted among tribal women aged 14-49 yr in Udupi taluk of Udupi district24. The study revealed that the prevalence of anaemia in these women was 55.9 per cent. Previous studies conducted among Jenu Kuruba tribes reported prevalence of anaemia in children to be 77.1 per cent25. According to WHO, if the prevalence of anaemia in a population is detected to be 40 per cent or higher, that population is to be considered severely anaemic26. All these studies conducted in tribal population clearly showed that they were anaemic and needed urgent nutritional attention.

In 2011, a study was carried out to assess the dietary status of the Jenu Kuruba and Yerava tribal children of Mysore district, Karnataka27. In the study 176 Jenu Kuruba children (80 boys and 96 girls) and 161 Yerava children (77 boys and 84 girls) aged 6-10 yr were included. The study revealed that the percentage of adequacy in energy and protein intake among children of both the tribal groups was more or less same, however, it was below the respective recommended dietary allowance. Intake of calcium, iron and beta-carotene was found to vary with age. The intake of beta-carotene was high among the Yerava children. Consumption of calcium rich food was more among Jenu Kurubas than in Yerava children.

Chronic and lifestyle diseases

A cross-sectional study was carried out among the individuals of the Jenu Kuruba tribe of the age group 20-60 yr in Hunsur taluk of Mysore district to estimate the prevalence of hypertension12. It is reported that 1,290 (80%) of the tribe in the taluk participated in the study, of whom 719 (55.7%) were women and 571 (44.3%) were men. Half of the subjects were in the age group of 20-30 yr. The study estimated prevalence of hypertension among this tribal community to be 21.7 per cent. Prevalence of hypertension among men was 28.2 per cent and among women it was 16.5 per cent which meant that one-third of the men and one-fifth of the women were hypertensive12. The prevalence of hypertension among Jenu Kuruba tribe found in this study was comparable to the composite nationwide data of National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB) which estimated prevalence of hypertension among rural adults to be 25 per cent28. This study corroborates the increasing recognition of burden of hypertension among the tribal population29,30,31.

A study was carried out among chronic alcoholics from the Koraga tribe to assess the extent of liver damage as compared to healthy controls and other alcoholics32. Serum and urine samples were collected from 28 Koraga alcoholics, 30 general alcoholics and 31 healthy controls and were analysed for liver function parameters and antioxidant markers. Results indicated that the extent of alcohol induced liver damage in Koraga subjects was comparatively lower than general alcoholics, even though alcohol consumption was found to be higher in them. The authors concluded that there might be some mechanism that rendered the Koraga tribe resistant to alcoholic liver damage.

Oral health

A study was carried out on 2605 people belonging to the Iruligas, a native Karnataka tribe, residing at 26 villages of Ramanagar district in Karnataka to assess their periodontal health status and oral hygiene practices33. The study revealed a relatively low prevalence of periodontal disease among these people perhaps because of their practice of using of chew stick which was observed in as many as 80 per cent of the tribal population.

Ethnomedicinal practices

Similar to the ethnic diversity of the State, the traditional health practices in Karnataka is also diversified with the changing cultures, diverse ecological conditions, geography, climate and vegetation. Each district in the State has its own and unique traditional health practices, which depends mainly on the culture of the tribal community and availability of the resources in terms of crude drugs, most of which come from the rich biodiversity of the Western Ghats region. The research works on ethnomedicine in Karnataka has been mostly limited to documentation of medicinal plants from specific geographical/tribal areas, for particular diseases or on specific tribes. Research studies with respect to traditional/tribal/folklore medicinal practices specific to a geographical area, taluka or district include reports from both tribal and non-tribal communities. In several such efforts, the ethnomedicinal practices from various districts like Tumkur34, Bengaluru35, Chikmagalur36, Kodagu37, Mysore38, Raichur39, Bidar40, Gadag41 and Belgaum42 have been documented. Documentations of traditional medicinal practices have also been made specific to talukas and locations as in coastal Karnataka43, Bhadravati44,45, Sringeri46, Sagar47,48 and Kukke Subramanya49.

The documentation of traditional practices for disease-specific conditions consists of information intermixed with both tribal and non-tribal communities for the region. The major efforts in these lines are for jaundice50,51, snake bites52, gynaecological disorders and reproductive care53,54, skin diseases55,56,57,58, oral health59, bone fractures60, wounds61 and for malaria62.

The studies carried out on specific tribes are only a few in number, many of which are not exhaustive. The ethnomedicinal practices from following tribes have been documented:

Jenu Kuruba: The less known ethnomedicinal uses of plants reported by Jenu Kuruba tribe of Mysore district was documented by Kshirsagar and Singh63. The report provided the scientific and local names, geographical distribution within the district, plant family, preparation, uses and the methods of administration of 25 medicinal plants traditionally used in Mysore, but less known to other regions. Another study documented the traditional medicinal knowledge of the tribe from Kodagu (Coorg) district64. The documentation was done through structured questionnaires in consultations with the tribal practitioners and patients that have resulted in the documentation of 20 medicinal plant species for treatment/cure of 21 diverse forms of ailments. The study underlines the potential of the ethnobotanical knowledge in this tribe and the need for the further documentation and research needs in this direction.

Khare vokkaliga: Khare-Vokkaliga is one of the small ethnic communities inhabiting Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka. Achar et al65 conducted the studies on their ethnomedicinal aspects and documented usage of 57 plant species for the treatment of 39 ailments. Among these, 20 species are being used to treat six infectious diseases and 44 species for 33 non-infectious diseases.

Siddis: Bhandary et al66 reported 98 preparations used by them for treatment of various ailments. These preparations were made out of 69 species of plants.

Soliga: The documentation of ethnobotanical plants used by the Soligas has been made67. The authors reported the utility of 57 species of plants by the tribe for treating various ailments. Later, the lifestyle, culture, rituals and traditional heath practices of Soliga tribe in Chamarajanagar district were outlined68. It was noted that Soligas maintained a continuous and intimate interaction with the forest, deriving most of their basic requirements from the forests. Due to their intimacy with the nature, the Soligas have a holistic outlook on life and their indigenous knowledge is also holistic in nature.

Kunabi: The ethnomedicobotany of the Kunabi tribe was documented by Harsha et al69. They documented 45 species of plants for the treatment of 24 ailments. Among the reported plants, six species were used for treatment of allergies and skin diseases, five for sores and inflammations and four each for fever, cuts, wounds and urinary tract infections.

Gowlies: Bhandary et al70 reported the plants used by the traditional practitioners of the Gowli tribe of Uttara Kannada district in Karnataka. They documented the use of 41 species of plants in the medicinal practices of the tribe. The details on parts used, method of preparations, dose and duration of treatment along with the botanical details of the plants have been provided in the report.

In Gulbarga, Rajasab and Isaq71 recorded 51 species of common plants used by Lambanis for their healthcare. The utility of 30 plant species for primary healthcare conditions among the ethnic groups like Halakki, Kadu kuruba and Lambani in Bidar district has also been reported40. The traditional usage of 25 species of legumes, including their use in health aspects, has been documented among ethnic fishermen groups like Best, Bovi, Gangamathasta, Mogaveera and Karvi from 12 locations in three sites of western coast of Karnataka72. Hiremath and Taranath73 reported 15 plants with 12 preparations as traditional phytotherapy for snake bites among the tribes such as Lambanis, Hakki-pikki, Jenu Kurubas and Iruligas from Chitradurga district. During the documentation of the plants for the treatment of herpes, Bhandary and Chandrashekhar74, reported 34 formulations for its treatment with 57 species of plants, especially those used by Koraga, Malekudiya and Hallakki Vokkaliga tribes from Uttara Kannada district of the State. Recently, Bhat et al58 reported 102 species of plants used to treat skin diseases from Uttara Kannada district, documented from various communities including tribes like Hallakki vokkaliga, Siddi, Kunbi and Gowli.

In spite of all these studies and reports, there exists a large gap in complete documentation of the ethnomedicinal knowledge and practice of tribes of Karnataka. The valuable knowledge of the vast ethnic population on the healing herbs of the region is fast eroding and is in immediate need of systematic, scientific, exhaustive and uniform documentation which can be subsequently validated through research and clinical evaluation or through reverse pharmacology approach serving the larger purpose of translating traditional knowledge into practice of health care.

Efforts from Government and non-Government organisations (NGOs)

The Department of Tribal Welfare was formed specifically to address the needs of STs in Karnataka. The concept of the Tribal Sub-Plan (TSP) and its counterpart the Special Component Plan (SCP) emerged in the National Fifth Five-Year Plan11. The objectives of the TSP are poverty alleviation, protection of tribal culture, education, health care and providing basic minimum infrastructure. Poverty alleviation includes programmes in agriculture, animal husbandry, sericulture, horticulture, village and small industries as well as all employment-generating schemes such as Swarna Jayanthi Swarozgar Yojana (SJSY). Tribal education is given importance by the State Government. Social Welfare Department of the State is looking after the educational needs of these communities. Various programmes are implemented to provide educational facilities to students belonging to the scheduled tribes. The State Government is opening nursery and women welfare centres, Asharm schools (free residential schools) pre-metric hostels, for boys and girls, etc. From 1995-1996 onwards Karnataka Government has started scholarship scheme for the ST children. The students from 1st to 10th standard can avail this privilege. Financial assistance is provided by the Social Welfare Department75.

Apart from the efforts made by the State Government some of the non-governmental agencies and associations, trusts and individuals have taken interest in tribal educational welfare programmes in Karnataka. Institutions such as Vivekananda Girijana Kalyan Kendra (VGKK) in Mysore district is a well-known centre working for the upliftment of the Soliga tribes. The centre has residential tribal school, vocational training and market facilities for tribal products75.

The role of NGOs in tribal welfare activities, though small, has been significant for introducing qualitative changes in the lives of the people. Vivekananda Girijana Kalyana Kendra, Swami Vivekananda Youth Movement, Development Through Education (DEED), Foundation for Educational Innovations in Asia (FEDINA), Coorg Organisation of Rural Development (CORD), Samagra Grameena Ashrama, Janashikshana Trust, Chintana Foundation, Samvriddi/Krupa, Vanavasi Kalyana Ashrama are some of the well-known NGOs involved in the tribal development in Karnataka. It is possible to make development work more effective and sustainable through engagement with the local community, which has a better understanding of its own socio-economic needs, traditions and culture than non-tribals. Their participation in programmes, funded by the Government and voluntary organizations helped build confidence in the people to utilize the services thus offered and has provided feedback for modification and re-orientation of programmes11. Under the India Population Project (IPP-9) project, the Health Department and NGOs trained tribal girls as ANMs and they were posted to sub-centres in remote tribal areas. These ANMs are now providing good healthcare services to tribal women and children11. Government-owned PHCs at Gumballi and Thithimathi were handed over to Karuna Trust and Vivekananda Foundation respectively and are being run as model PHCs11.

In B.R. Hills, Mysore, Vivekanada Girijana Kalyan Kendra (VGKK), an NGO, is promoting the traditional knowledge systems of tribals and has integrated traditional healthcare system with modern medicine. Tribal knowledge of herbal medicines is also being promoted by them11. However, the degree of effectiveness of various schemes in terms of programme implementation in these sectors is not evident in the three critical areas of health, education and poverty reduction. The magnitude of the problem is so great that a large percentage of tribal families are poor and lack access to resources that would improve their education and health status. The human development status of the tribes of Karnataka is more than a decade behind the rest of the population of the State and thus they remain poorest and most deprived of all sub-populations in the State11.

The present review attempts to highlight the limited research carried out on the health of the ethnic tribes of Karnataka. It identifies the gaps that need to be filled up to understand the health issues for better health care management of these tribes. It also underscores the potential of integration of the rich traditional practices of the ethnic tribes with present day knowledge and healthcare. Concerted inter-sectorial efforts are needed from policy makers, researchers, care providers, non-profit and social organization to improve the health status of the tribes of Karnataka.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the encouragement and motivation from Dr Neeru Singh, Director, National Institute for Research in Tribal Health (ICMR), Jabalpur, and thank the Bio-Medical Informatics Centre of RMRC, Belgaum, for compilation of data needed for the study.

References

- 1.Boruah M. In the dark about Rajyotsava in Bangalore. DNA India. 2010 Nov 2; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Government of India, Census. 2011. [accessed on May 7, 2014]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/population_enumeration.aspx .

- 3.Lal RB, Padmanabham SV, Mohideen A, editors. Part I. Vol. 22. Mumbai: popular prakashan; 2003. People of India Gujarat; pp. 108–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhanu BV, Bhatnagar BR, Bose DK, Kulkarni VS, Sreenath J, editors. Part I. Vol. 30. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan; 2004. People of India Maharashtra. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel H, Maralusiddaiah M, Srinivas BM, Vijayendra BR. Koraga. In: Chaudhuri SK, Chaudhuri SS, editors. Primitive tribes in contemporary India: Concept, ethnography and demography 1. New Delhi: Mittal Publications; 2005. p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malnutrition high among Koraga children. The Hindu. 2012 Feb 11; [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshua Project-Ministry Act 081. A ministry of the U.S. Center for World Mission. Frontier Mission Fellowship. [accessed on May 7, 2014]. Available from http://joshuaproject.net .

- 8.Demographic Status of Scheduled Tribe Population of India. 2013. [accessed on May 7, 2014]. Available from: http://www.tribal.gov.in/WriteReadData/CMS/Documents/201306110208002203443DemographicStatusofScheduledTribePopulationofIndia.pdf .

- 9.Bistee AR, Sreeramulu G. Status of scheduled tribes in Karnataka. Indian Streams Res J. 2014;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Economic survey of Karnataka, 2012-13. [accessed on May 7, 2014]. Available from: http://planning.kar.nic.in/node/128.html .

- 11.Government of Karnataka. Status of Scheduled Tribes of Karnataka. In: Karnataka Human Development Report. 2005. [accessed on May 7, 2014]. Available from: http://planning.kar.nic.in/sites/planning.kar.nic.in/files/khdr2005/English/Main%20Report/10-chapter.pdf .

- 12.Hathur B, Basavegowda M, Ashok NC. Hypertension: An emerging threat among tribal population of Mysore; Jenu Kuruba tribe diabetes and hypertension study. Int J Health Allied Sci. 2013;2:270–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanjunda DC. Functioning of primary health centers in the selected tribal districts of Karnataka-India: some preliminary observations. Online J Health Allied Scs. 2011;10:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mavalankar D. Primary Health Care under Panchayati Raj: Perceptions of officials from Gujarat. Asian J Dev Matters. 2009;4:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah AM, Tamang R, Moorjani P, Rani DS, Govindaraj P, Kulkarni G, et al. Indian Siddis: African descendants with Indian admixture. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar S. Genetic Profile of Jenu Kuruba, Betta Kuruba and Soliga Tribes of Southern Karnataka and their phylogenetic relationships. Anthropologist. 2008;10:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guthigar M, Vaswani V. Availability and accessibility of the basic facilities including health care by a Primitive Tribal Group of South India - An exploratory study. Res J Social Sci Manage. 2013;3:169–75. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiwari BK, Rao VG, Mishra DK, Thakur CSS. Infant-feeding practices among Kol tribal community of Madhya Pradesh. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:228. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dakshayani B, Gangadhar MR. Breast feeding practices among the Hakkipikkis: a tribal population of Mysore district, Karnataka. EthnoMed. 2008;2:127–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhardwaj AK, Swami HM, Gupta BP, Ahluwalia SK, Vaidya NK. Infant feeding practices among tribals. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 1991;22:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deshpande SG, Zodpey SP, Vasudeo ID. Infant feeding practices in a tribal community of Melghat region in Maharashtra state. Indian J Med Sci. 1996;50:4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renuka M, Rakesh A, Babu NM, Santosh KA. Nutritional status of Jenukuruba preschool children in Mysore district, Karnataka. J Res Med Sci. 2011;1:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005-06. Mumbai: IIPS; 2008. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamath R, Majeed JA, Chandrasekaran V, Pattanshetty SM. Prevalence of anaemia among tribal women of reproductive age in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka. J Fam Med Primary Care. 2013;2:345–8. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.123881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jai Prabhakar SC, Gangadhar MR. Prevalence of anemia in Jenukuruba primitive tribal children of Mysore District, Karnataka. Anthropologist. 2009;11:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geneva: WHO; 2011. World Health Organization (WHO). Hemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jai Prabhakar SC, Gangadhar MR. Dietary status among Jenu Kuruba and Yerava tribal children of Mysore District, Karnataka. Anthropologist. 2011;13:159–62. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyderabad: NNMB; 2006. National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB). Diet and nutritional status of population and prevalence of hypertension among adults in rural areas. NNMB Technical Report No 24; pp. 35–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kusuma YS, Babu BV, Naidu JM. Prevalence of hypertension in some cross-cultural populations of Visakhapatnam district, South India. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:250–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tiwari RR. Hypertension and epidemiological factors among tribal labour population in Gujarat. Indian J Public Health. 2008;52:144–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerketta AS, Bulliya G, Babu BV, Mohapatra SS, Nyak RN. Health status of the elderly population among four primitive tribes of Orissa India: A clinical epidemiological study. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;42:53–9. doi: 10.1007/s00391-008-0530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prakash M, Anwar N, Tilak P, Shetty MS, Prabhu LS, Kedage V, et al. A comparative study between alcoholics of Koraga community, alcoholics of general population and healthy controls for antioxidant markers and liver function parameters. Online J Health Allied Scs. 2009;8:8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadanakuppe S, Bhat PK. Oral health status and treatment needs of Iruligas at Ramanagara District, Karnataka, India. West Indian Med J. 2013;62:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoganarasimhan SN, TogunashiVS, Murthy KRK, Govindaiah Medicobotany of Tumkur district, Karnataka. J Econ Taxon Bot. 1982;3:391–406. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pushpalata H, Sauthan JR, Pattanshetty JK, Holla BV. Folk medicine from some rural areas of Bangalore district. Aryavaidyan. 1990;12:215–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gopalkumar K, Vijayalakshmi B, Shantha TR, Yoganarasimhan SN. Plants used in Ayurveda from Chickmagalur district, Karnataka. J Econ Taxon Bot. 1991;15:379–89. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kshirsagar RD, Singh NP. Less known ethnomedicinal uses of plants in Coorg district of Karnataka state, southern India. Ethnobotany. 2000;12:12–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kshirsagar RD, Singh NP. Some less known ethnomedicinal uses from Mysore and Coorg districts, Karnataka State, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75:231–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kattimani KN, Munikrishnappa PM, Hussain SA, Reddy PN. Use plants as medicine under semi-arid tropical climate of Raichur district of north Karnataka. J Med Arom Pl Sci. 2001;22-23:607–11. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prashantkumar P, Vidyasagar GM. Documentation of traditional knowledge on medicinal plants of Bidar district, Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2006;5:295–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramana P, Patil SK, Sankri G. Loristic diversity of Magadi wetland area in Gadag district, Karnataka. Proceedings of Taal 2007: The 12th World Lake Conference. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Upadhya V, Mesta D, Hegde HV, Bhat S, Kholkute SD. Ethnomedicinal plants of belgaum Region, Karnataka. J Econ Taxon Bot. 2010;33:300–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhandary MJ, Chandrashekar KR. Glimpses of ethnic herbal medicine of costal Karnataka. Ethnobotany. 2002;14:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parinitha M, Harish GU, Vivek NC, Mahesh T, Shivanna MB. Ethno-botanical wealth of Bhadra wild life sanctuary in Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2004;3:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shivanna MB, Rajakumar N. Ethno-medico-botanical knowledge of rural fold in Bhadravathi taluk of Shimoga district, Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2010;9:158–62. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prakasha HM, Krishnappa M. People's knowledge on medicinal plants in Sringeri taluk, Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2006;5:353–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajakumar N, Shivanna MB. Traditional herbal medicinal knowledge in Sagar taluk of Shimoga district, Karnataka, India. Indian J Natural Products Resources. 2010;1:102–8. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poornima G, Manasa M, Rudrappa D, Prashith Kekuda TR. Medicinal plants used by herbal healers in Narasipura and Manchale villages of Sagara Taluk, Karnataka, India. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2012;1:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiddamallayya N, Yasmeen AYL, Gopukumar K. Medico-botanical survey of Kumar parvatha Kukke subramanya, Mangalore, Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2010;9:96–9. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shantamma C, Sudarshana MS, Rachaih Flaveria trinervosa - a new herb to cure jaundice. Ancient Sci Life. 1986;6:109–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hebbar SS, Harsha VH, Hegde GR, Shripathi V. Ethno-medicobotanical survey in Dharwad-plants used for Jaundice. Bull Bot Sur India. 2004;46:268–72. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhandary MJ, Chandrashekar KR. Treatment of poisonous snake-bites in the ethnomedicine of coastal Karnataka. J Med Arom Pl Sci. 2001;22(23):505–10. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hegde HV, Hegde GR, Kholkute SD. Herbal care for reproductive health: Ethno-medicobotany from Uttara Kannada district in Karnataka, India. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2007;13:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vidyasagar GM, Prashantkumar P. Traditional herbal rededies for gynecological disorders in women of Bidar district, Karnataka, India. Fitoterapia. 2007;78:48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maruthi KR, Krishna V, Manjunatha BK, Nagaraja VP. Traditional medicinal plants of Davanagere district, Karnataka- with reference to cure skin diseases. Environ Ecol. 2000;18:441–6. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hegde HV, Hebbar SS, Shripathi V, Hegde GR. Ethnomedicobotany of Uttara Kannada District in Karnataka, India - plants in treatment of skin diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prashantkumar P, Vidyasagar GM. Traditional knowledge on medicinal plants used for the treatment of skin diseases in Bidar district, Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2008;7:273–6. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhat P, Hegde GR, Hegde G, Mulgund GS. Ethnomedicinal plants to cure skin diseases - An account of traditional knowledge in the coastal parts of Central Western Ghats, Karnataka, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hebbar SS, Hegde HV, Shripathi V, Hegde GR. Ethnomedicine of Dharwad district in Karnataka, India - plants used in oral health care. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;94:261–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Upadhya V, Hegde HV, Bhat S, Hurkadale PJ, Kholkute SD, Hegde GR. Ethno-medicinal plants used to treat bone fracture from North- Central Western Ghats of India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;142:557–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhat P, Hegde G, Hegde GR. Ethnomedicinal practices in different communities of Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka for treatment of wounds. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;143:501–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prakash BN, Unnikrishnan PM. Ethnomedical survey of herbs for the management of malaria in Karnataka, India. Ethnobot Res Applications. 2013;11:289–98. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kshirsagar RD, Singh NP. Less known ethnomedicinal uses of plants reported by Jenu kuruba tribe of Mysore district, southern India. Ethnobotany. 2000;12:118–22. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nanjunda DC. Ethno-medico-botanical Investigation of Jenu Kuruba Ethnic Group of Karnataka State, India. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2010;9:161–9. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Achar SG, Rajkumar N, Shivanna MB. Ethno-medico-botanical knowledge of Khare-vokkaliga community in Uttara Kannada District of Karnataka, India. J Compliment Integr Med. 2010;7:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhandary MJ, Chandrashekar KR, Kaveriappa, KM Medical ethnobotany of the Siddis of Uttarakannada district, Karnataka, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;47:149–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01274-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hosagoudar VB, Henry AN. Plants used in birth control and reproductive ailments by Soligas of B.R. Betta in Mysore district of Karnataka. Ethnobotany. 1993;5:117–8. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Madegowda C. Traditional knowledge and conservation. Econ Polit Wkly. 2009;44:65–9. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harsha VH, Hebbar SS, Hegde GR, Shripathi V. Ethnomedical knowledge of plants used by Kunabi Tribe of Karnataka in India. Fitoterapia. 2002;73:281–7. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhandary MJ, Chandrashekar KR, Kaveriappa KM. Ethnobotany of Gawlis of Uttara Kannada District, Karnataka. J Econ Taxon Bot. 1996;12:244–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01274-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rajasab AH, Isaq M. Documentation of folk knowledge on edible wild plants of North Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2004;3:419–29. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bhagya B, Sridhar KR. Ethnobiology of coastal sand dunes of Southwest coast of India. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2009;8:611–20. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hiremath VT, Taranath TC. Traditional phytotherapy for snakebites by tribes of Chitradurga district, Karnataka, India. Ethnobot Leaflets. 2010;14:120–5. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhandary MJ, Chandrashekhar KR. Herbal therapy for herpes in the ethnomedicine of coastal Karnataka. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2011;10:528–32. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shinde VM. Educational scenario of Scheduled Tribes in Karnataka. Int Indexed Referred Res J. 2012;1:26–7. [Google Scholar]