Abstract

Deeper insight into the molecular pathways that orchestrate skeletal myogenesis should enhance our understanding of, and ability to treat, human skeletal muscle disease. It is now widely appreciated that nutrients, such as molecular oxygen (O2), modulate skeletal muscle formation. During early stages of development and regeneration, skeletal muscle progenitors reside in low O2 environments before local blood vessels and differentiated muscle form. Moreover, low O2 availability (hypoxia) impedes progenitor-dependent myogenesis in vitro through multiple mechanisms, including activation of hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF1α). However, whether HIF1α regulates skeletal myogenesis in vivo is not known. Here, we explored the role of HIF1α during murine skeletal muscle development and regeneration. Our results demonstrate that HIF1α is dispensable during embryonic and fetal myogenesis. However, HIF1α negatively regulates adult muscle regeneration after ischemic injury, implying that it coordinates adult myogenesis with nutrient availability in vivo. Analyses of Hif1a mutant muscle and Hif1a-depleted muscle progenitors further suggest that HIF1α represses myogenesis through inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling. Our data provide the first evidence that HIF1α regulates skeletal myogenesis in vivo and establish a novel link between HIF and Wnt signaling in this context.

KEY WORDS: HIF1α, Wnt, Myogenesis, Oxygen, Regeneration, Mouse

Highlighted article: Hypoxia inducible factor 1α is dispensable for embryonic myogenesis but, via the inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling, negatively regulates muscle regeneration in adult mice.

INTRODUCTION

Unraveling the complex pathways that regulate mammalian skeletal myogenesis, or muscle formation, should enhance the development of novel therapies for diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy and critical limb ischemia in peripheral arterial disease (PAD) (Hiatt, 2001; Tedesco et al., 2010). Differentiated muscle fibers originate from skeletal muscle stem/progenitor cells (SMSPCs) via a coordinated network of transcription factors (Bentzinger et al., 2012). SMSPCs express the transcription factor PAX3 in the early embryo and its homolog PAX7 in the fetus and adult, and they are essential for embryonic and adult myogenesis, respectively. In addition, the muscle regulatory factors (MRFs) MYOD1 and myogenin (MYOG) control gene expression to specify SMSPCs for the skeletal muscle fate and promote myogenic differentiation (Bentzinger et al., 2012).

Extracellular cues from Wnt ligands are established regulators of myogenesis (von Maltzahn et al., 2012b). Wnt engages LDL-related protein (LRP)/Frizzled complexes at the cell surface, impairing the β-catenin degradation machinery and instead promoting its cytoplasmic accumulation through a canonical axis. β-catenin then translocates to the nucleus where it binds LEF/TCF proteins to activate the transcription of specific target genes (e.g. Axin2 and Pitx2). This canonical Wnt pathway is capable of promoting SMSPC differentiation, which is essential for both embryonic myogenesis and adult muscle regeneration (von Maltzahn et al., 2012b). The non-canonical Wnt signaling cascade, which includes the planar cell polarity and Akt/mTOR pathways, modulates myogenic processes by regulating the symmetric expansion of SMSPCs and myofiber growth (Le Grand et al., 2009; von Maltzahn et al., 2012a).

Local nutrients, such as molecular oxygen (O2), also influence myogenesis, as SMSPCs reside in a hypoxic microenvironment in both embryonic and adult settings. Early embryonic somites containing PAX3+ precursors express markers of low O2 availability (hypoxia), such as hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), prior to the generation of intersomitic blood vessels and embryonic muscle (Relaix et al., 2005; Provot et al., 2007). In murine models of PAD (Paoni et al., 2002; Borselli et al., 2010), hindlimb ischemia leads to adult muscle injury and subjects these damaged fibers, as well as adjacent PAX7+ progenitors, to O2 deprivation. Upon revascularization and restored perfusion, muscle fiber regeneration ensues. O2 is likely to play a regulatory role in these contexts, as hypoxic culture conditions maintain SMSPCs in an undifferentiated state (Di Carlo et al., 2004; Gustafsson et al., 2005; Yun et al., 2005; Ren et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2012; Majmundar et al., 2012). Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether O2 and O2-sensitive factors regulate skeletal myogenesis in vivo.

Low O2 availability impedes myogenesis in vitro through multiple mechanisms, including activation of HIF1α. HIF1α mediates the primary response to physiological and pathological hypoxia throughout life (Simon and Keith, 2008; Majmundar et al., 2010). It becomes stabilized in hypoxic settings and dimerizes with ARNT (also known as HIF1β) to form the HIF transcription factor (Majmundar et al., 2010). HIF is required during embryogenesis in numerous developmental programs, including the blood, vasculature, placenta, endochondral bone and cardiac muscle (Simon and Keith, 2008). Moreover, HIF1α promotes neoangiogenesis and reperfusion in hindlimb ischemia models of PAD (Bosch-Marce et al., 2007). Although HIF1α represses SMSPC differentiation in vitro (Gustafsson et al., 2005; Ren et al., 2010; Majmundar et al., 2012), its role during muscle development or regeneration remains unclear.

In this study, we employed multiple mouse models to determine whether the O2-responsive factor HIF1α regulates skeletal myogenesis in vivo. The Hif1a gene was ablated in SMSPCs in order to dissect its function during muscle development or regeneration. Surprisingly, Hif1a deletion failed to impact skeletal muscle formation during embryonic stages. Instead, HIF1α negatively regulates adult skeletal muscle regeneration upon injury through inhibition of canonical Wnt pathways, demonstrating its selective role in adult myogenesis.

RESULTS

Pax3Cre/+-mediated Hif1a deletion does not alter skeletal muscle development

Early embryonic somites containing PAX3+ precursors exhibit HIF1α expression prior to the generation of intersomitic blood vessels and embryonic muscle (Relaix et al., 2005; Provot et al., 2007). The significance of its expression in muscle development was previously unclear, as Hif1a−/− mice succumb to vascular and placental defects before embryonic muscle development is complete (Relaix et al., 2005; Simon and Keith, 2008). Thus, we employed Pax3Cre/+ mice to assess the role of HIF1α during muscle development. In these mice, Cre-mediated recombination occurs in PAX3+ presomitic mesoderm at E8.5 and later in PAX3+ embryonic muscle progenitors (Engleka et al., 2005). An R26lacZ/+ allele demonstrated efficient and muscle-specific Cre activity in Pax3Cre/+Hif1aΔ/Δ animals, as Cre+ mice retained β-galactosidase activity selectively in skeletal muscle (supplementary material Fig. S1A).

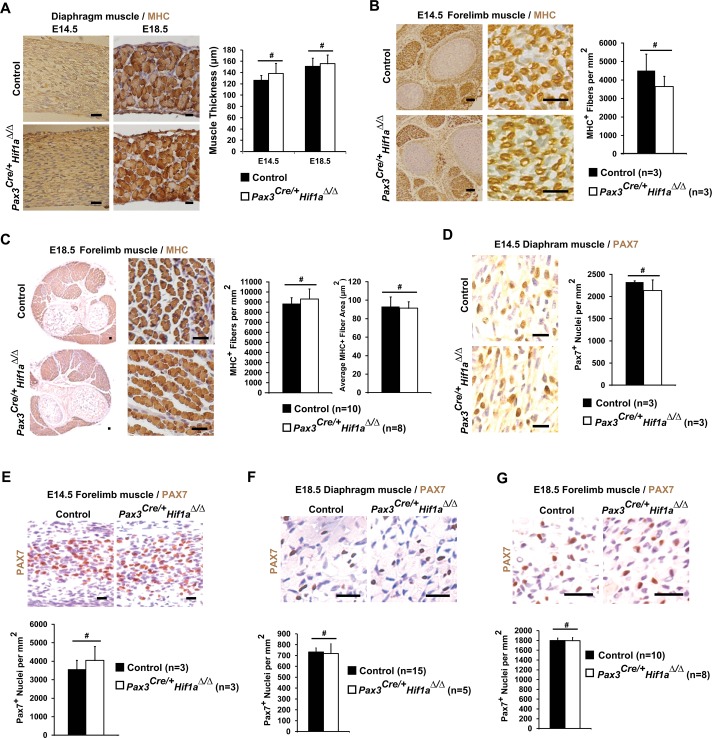

Because HIF1α plays essential roles during embryogenesis in numerous developmental programs, including cardiac muscle (Simon and Keith, 2008), we hypothesized that HIF1α is important for SMSPC maintenance and embryonic muscle development. However, E14.5 Pax3Cre/+Hif1aΔ/Δ mice developed comparable muscle area to control mice, as determined by myosin heavy chain (MHC) staining of diaphragm and forelimb muscles (Fig. 1A,B). Fetal muscle area was also similar in E18.5 experimental and control animals (Fig. 1A,C). These data suggest that HIF1α is not essential for embryonic or fetal skeletal muscle formation.

Fig. 1.

Pax3Cre/+-mediated Hif1a deletion does not alter mouse skeletal muscle development. Representative images and quantification of MHC (A-C) or PAX7 (D-G) IHC of fetal diaphragm (A,D,F) and fetal limb (B,C,E,G) muscles at E14.5 (A,B,D,E) and E18.5 (A,C,F,G). For all measurements, group averages are graphed. Error bars represent s.e.m. #Not significantly different by Student's t-test (P>0.05). Scale bars: 20 µm.

We then evaluated whether HIF1α modestly influences SMSPC maintenance, such that Hif1a mutants fail to display muscle defects until later in life (i.e. postnatally). However, PAX7+ progenitor density was unaffected by Hif1a deletion at E14.5 (Fig. 1D,E), suggesting that these progenitors are appropriately generated from PAX3+ precursors in late embryonic myogenesis (Bentzinger et al., 2012). PAX7+ cell numbers in Pax3Cre/+Hif1aΔ/Δ fetuses were also comparable to controls at E18.5 (Fig. 1F,G), indicating they are appropriately maintained during fetal myogenesis. We conclude that HIF1α in the myogenic lineage does not regulate PAX7+ progenitor homeostasis during embryonic development.

Pax3Cre/+Hif1aΔ/Δ mice exhibited non-muscle phenotypes, including perinatal lethality with complete penetrance (supplementary material Fig. S1B). Pax3Cre/+Hif1aΔ/Δ mice manifested defects in tissues derived from PAX3+ somitic cells: histological examination and von Kossa staining revealed insufficient rib bone calcification (supplementary material Fig. S1C). These data agree with a previous report showing that HIF1α is required for bone ossification and perinatal viability (Schipani et al., 2001), and prove the importance of HIF1α expression in early embryonic somites (Provot et al., 2007). Conversely, slow muscle fiber formation is independent of HIF1α status (supplementary material Fig. S1D), confirming that HIF1α in PAX3+ cells is not essential for embryonic myogenesis. Cre-mediated recombination of the Hif1a locus in embryonic muscles was efficient (supplementary material Fig. S1E).

We considered whether the related subunit HIF2α (also known as EPAS1) (Majmundar et al., 2010) serves a compensatory or redundant role with HIF1α during skeletal muscle development. We examined the effect of Pax3Cre/+-mediated deletion of Arnt, which encodes the essential binding partner for both HIF1α and HIF2α (Majmundar et al., 2010). E18.5 Pax3Cre/+ArntΔ/Δ fetuses exhibited comparable fetal muscle size and PAX7+ progenitor density to control mice (supplementary material Fig. S1F-H), suggesting neither HIFα subunit in PAX3+ cells regulates fetal progenitor maintenance or muscle formation during embryogenesis.

Our observations in Pax3Cre/+Hif1aΔ/Δ mice suggest that HIF1α is not required for skeletal muscle development. This was unexpected because the Notch pathway, which was previously shown to mediate the effects of HIF1α on myogenesis in vitro (Gustafsson et al., 2005), is required during embryonic muscle formation (Bentzinger et al., 2012). Nevertheless, these findings do not exclude the possibility that HIF1α regulates adult skeletal myogenesis. Multiple studies have shown that embryonic, fetal and adult myogenesis have distinct as well as common genetic requirements (Bentzinger et al., 2012). Moreover, effects of HIF1α on myogenesis in vitro have been demonstrated in adult SMSPCs (Ren et al., 2010; Majmundar et al., 2012) and might reflect an adult-specific role for HIF1α in skeletal muscle development.

Pax7IresCreER/+-mediated deletion of Hif1a accelerates muscle regeneration after ischemic injury

To determine whether HIF1α regulates adult skeletal myogenesis, we employed the femoral artery ligation (FAL) model of PAD (Borselli et al., 2010; Paoni et al., 2002). In this model, hindlimb ischemia injures skeletal muscle. As revascularization processes restore limb perfusion, muscle regeneration occurs (Paoni et al., 2002; Borselli et al., 2010). Consistent with previous reports (Lee et al., 2004; Bosch-Marce et al., 2007), HIF1α protein accumulated in injured extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle 2 days after ligation (when perfusion was low) and then declined as blood flow returned (supplementary material Fig. S2A,B). Conversely, Myog mRNA levels in EDL muscle decreased at day 2 relative to uninjured muscle, and subsequently rose (supplementary material Fig. S2C). The inverse relationship between HIF1α and Myog suggests that HIF1α might inhibit adult muscle regeneration in vivo.

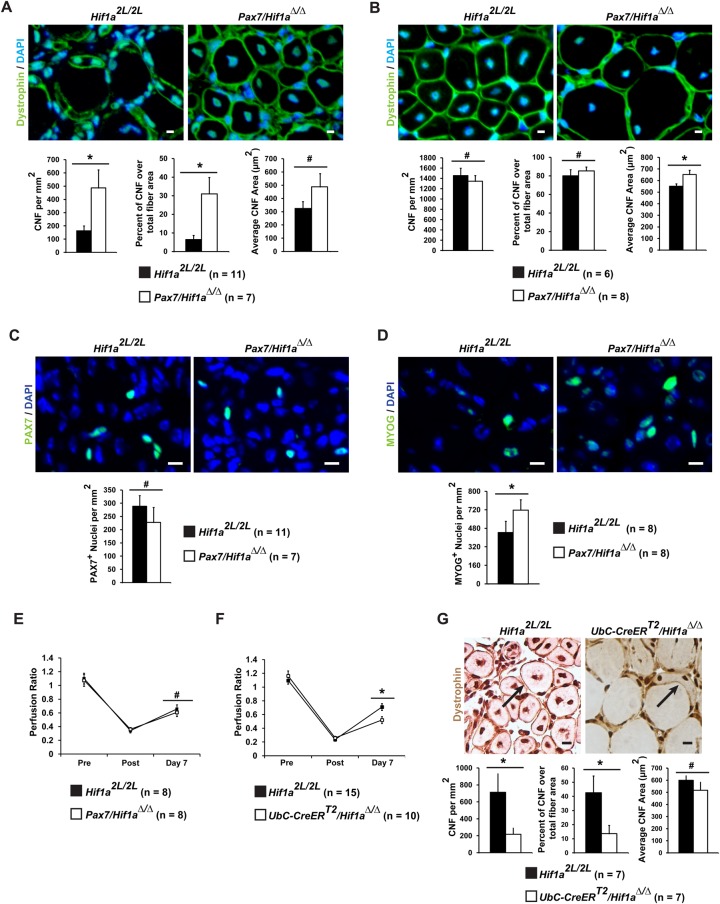

To further prove this point, we analyzed Pax7IresCreER/+ mice, in which conditional recombination occurs in PAX7+ SMSPCs upon tamoxifen treatment (Nishijo et al., 2009). Adult Pax7IresCreER/+ Hif1aΔ/Δ (Pax7/Hif1aΔ/Δ) mice were treated with tamoxifen to initiate Hif1a ablation (supplementary material Fig. S2D), and FAL was performed. Seven days after ligation, EDL muscle from Pax7/Hif1aΔ/Δ mice displayed evidence of increased regeneration relative to controls (Fig. 2A; supplementary material Fig. S2E), while average fiber area trended higher in mutants but was not statistically significant (Fig. 2A). After 14 days, when regeneration in both groups was elevated relative to day 7 (Fig. 2A,B), central nucleated fiber (CNF) density and the percentage of CNF among total fiber area were comparable in control and Hif1aΔ/Δ muscle (Fig. 2B). Of note, HIF1α-deficient muscle displayed significantly larger CNFs than controls at day 14 (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that HIF1α inhibits fiber growth at this later stage. Overall, these results indicate that HIF1α loss accelerates features of skeletal muscle regeneration, i.e. fiber formation and growth, providing the first evidence that HIF1α regulates skeletal myogenesis in vivo.

Fig. 2.

Pax7IresCreER/+-mediated Hif1a deletion accelerates muscle regeneration. (A-D) Representative images and quantification of dystrophin (A,B), PAX7 (C) or MYOG (D) IF on injured EDL muscle 7 days (A,C,D) and 14 days (B) following FAL. (E) Limb perfusion assessed by laser Doppler imaging before FAL (Pre), immediately following FAL (Post), and 7 days following FAL (Day 7). Perfusion ratio refers to flow in the ligated limb normalized to that in non-ligated collateral limb. (F) Limb perfusion measured by diffuse correlation spectroscopy (times as in E). (G) Representative images and quantification of dystrophin IHC on injured EDL muscle 7 days following FAL. Arrows point to a representative CNF in two muscle groups. For all measurements, group averages are graphed. Error bars represent s.e.m. *P<0.05, #P>0.05 (Student's t-test). Scale bars: 10 µm.

We next considered whether Pax7/Hif1aΔ/Δ mice exhibit elevated fiber production at the expense of increased PAX7+ SMSPC differentiation and consumption. When we measured PAX7+ progenitor numbers in injured muscles, we found that control and mutant mice exhibited comparable density (Fig. 2C) and basal lamina localization (supplementary material Fig. S2F) of PAX7+ cells at day 7 post injury. However, the density of MYOG+ cells (Fig. 2D) and extent of fibrosis (supplementary material Fig. S2G) were significantly higher in mutant than in control muscles. These results suggest that the pathophysiological stabilization of HIF1α does not alter the number of PAX7+ SMSPCs 7 days after ischemic injury, but rather inhibits the lineage progression of myocytes derived from PAX7+ cells.

Of note, the phenotype of Hif1a deletion in PAX7+ SMSPCs differs considerably from the effects of global Hif1a deletion. Perfusion resumed at the same rate in control and Pax7/Hif1aΔ/Δ mice after FAL (Fig. 2E). However, adult Ubc-CreERT2/Hif1aΔ/Δ mice, in which tamoxifen administration results in global Hif1a deletion (Gruber et al., 2007) (supplementary material Fig. S2H,I), displayed impaired reperfusion after FAL (Fig. 2F). This confirms the established role of global HIF1α expression in revascularization after ischemic injury (Majmundar et al., 2010). Consistent with this result, global HIF1α depletion impaired skeletal muscle regeneration in EDL muscle (Fig. 2G). We conclude that whereas HIF1α expression in skeletal muscle lineages constrains muscle regeneration, its expression in other tissues (e.g. endothelial or inflammatory cells) supports reperfusion and promotes muscle regeneration after ischemic injury.

HIF1α represses canonical Wnt signaling during adult skeletal myogenesis

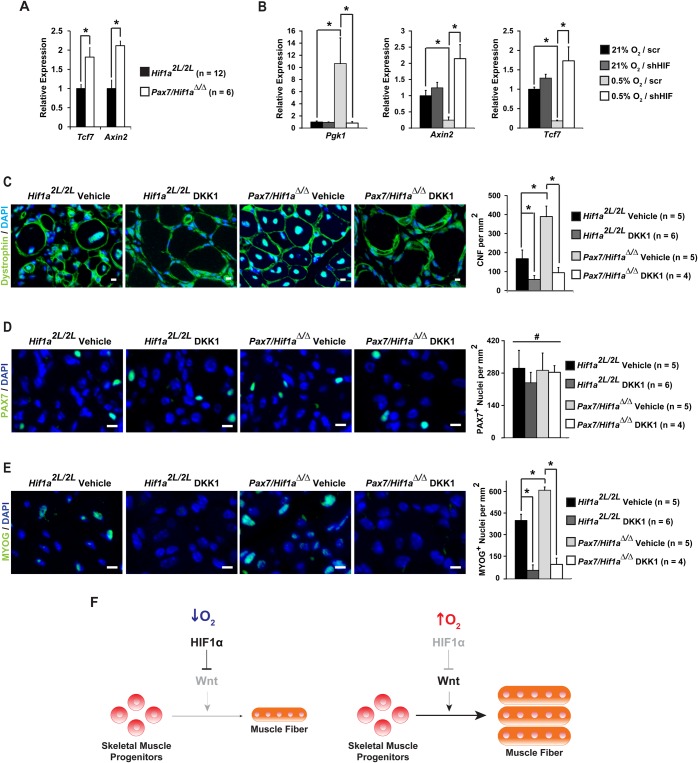

Hif1a deletion in PAX7+ SMSPCs is likely to dysregulate pathways important for muscle fiber regeneration. We evaluated the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which is known to promote adult muscle restoration upon injury (von Maltzahn et al., 2012b). HIF1α was previously shown to regulate Wnt signaling in a context-dependent manner, activating Wnt in stem cells and repressing it in colon carcinoma (Kaidi et al., 2007; Mazumdar et al., 2010a). We posited that muscle regeneration is accelerated in Hif1a mutant mice secondary to Wnt/β-catenin activation. In support of this notion, injured muscle from Pax7/Hif1aΔ/Δ mice exhibited elevated expression of the Wnt target genes Axin2 and Tcf7 (Fig. 3A), of which Tcf7 encodes a crucial β-catenin co-factor (von Maltzahn et al., 2012b).

Fig. 3.

HIF1α represses canonical Wnt signaling during adult skeletal myogenesis. (A) Relative Axin2 and Tcf7 mRNA levels detected in mouse EDL muscles 2 days after FAL. (B) Relative expression of Pgk1, Axin2 and Tcf7 in C2C12 myoblasts transduced with scrambled shRNA (scr) or Hif1a targeting shRNA (shHIF). Cells were differentiated for 48 h in 21% or 0.5% O2. (C-E) Representative images and quantification of dystrophin, PAX7 and MYOG IF on injured EDL muscle 7 days following FAL, in the presence or absence of the Wnt inhibitor DKK1. For all measurements, group averages are graphed. Error bars represent s.d., except s.e.m. in A. *P<0.05, #P>0.05 (Student's t-test). Scale bars: 10 µm. (F) Selective role of HIF1α during adult muscle regeneration by modulating Wnt signaling in response to O2 levels. At low O2 levels (↓O2), HIF1α inhibits myogenesis through repression of Wnt signaling. As O2 levels rise (↑O2) HIF1α protein diminishes, leading to increased Wnt activity and accelerated myogenesis.

To explore this mechanism further, we employed C2C12 myoblasts as an established tissue culture model of adult myogenesis and evaluated the effect of hypoxia-activated HIF1α on Wnt signaling in vitro. Transcription of the established HIF1α target phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (Pgk1) was increased in differentiating myoblasts cultured at 0.5% O2 (‘hypoxia’) relative to cells cultured at 21% O2 (‘normoxia’), whereas both Axin2 and Tcf7 mRNA levels were decreased (Fig. 3B). These effects are HIF1α dependent, since shRNA-mediated Hif1a inhibition (supplementary material Fig. S3A) abrogated Pgk1 induction as well as Axin2 and Tcf7 repression in hypoxia (Fig. 3B). These findings are consistent with transcriptional changes observed in vivo (Fig. 3A) and suggest that HIF1α blocks canonical Wnt signaling during skeletal myogenesis.

To further test whether HIF1α regulates skeletal myogenesis by modulating the Wnt pathway, the Wnt inhibitors dickkopf homolog 1 (DKK1) and secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (sFRP3; also known as FRZB) were administered (supplementary material Fig. S3B) (von Maltzahn et al., 2012b). As expected, C2C12 cell differentiation was inhibited by hypoxia, which was partially alleviated by Hif1a inhibition (supplementary material Fig. S3C). The increased differentiation observed in hypoxic Hif1a-depleted cells was suppressed by DKK1 and sFRP3 to the levels detected in hypoxic control cells (supplementary material Fig. S3D). More importantly, these in vitro results can be recapitulated in vivo, as intramuscular administration of DKK1 greatly impaired the effects of Hif1a deletion on muscle regeneration without affecting PAX7+ progenitor density (Fig. 3C-E). Collectively, these results demonstrate that HIF1α negatively regulates skeletal myogenesis through inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling.

DISCUSSION

HIF1α provides a core response to low O2 availability in numerous physiological and pathological settings during embryonic and adult life (Simon and Keith, 2008; Majmundar et al., 2010). Here we report that HIF1α is unexpectedly dispensable for skeletal muscle development, and instead plays a selective role during adult muscle regeneration by modulating Wnt signaling (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, Hutcheson et al. (2009) have previously deleted β-catenin from PAX3+ lineages and demonstrated that β-catenin is required for dermomyotome and myotome formation, but not for subsequent axial myogenesis during embryonic development. In addition, HIF1α is capable of suppressing Wnt signaling through direct and indirect mechanisms: first, HIF1α directly associates with β-catenin and competes for its interaction with T-cell factor 4 (TCF4), a crucial Wnt co-factor (Kaidi et al., 2007); second, HIF1α binds human arrest defective 1 (hARD1; NAA20), a protein responsible for β-catenin acetylation (Lim et al., 2008), and the HIF1α-hARD1 interaction dissociates hARD1 from β-catenin, preventing β-catenin acetylation and activation (Lim et al., 2008). However, these interactions were defined by biochemical assays, and whether they occur in vivo during muscle development awaits further investigation. We found that Pax3Cre-specific Hif1a deletion did not cause any observable changes in embryonic myogenesis, suggesting that HIF1α/β-catenin crosstalk does not occur during dermomyotome and myotome formation, and that HIF regulation of Wnt signaling during myogenesis is likely to be adult specific.

Furthermore, we observed that Hif1a deletion in PAX7+ satellite cells leads to increased CNF density (day 7 post injury) and enhanced hypertrophic growth (day 14) in regenerated muscle fiber. However, satellite cell density examined at day 7 after injury remained constant regardless of HIF1α status, suggesting that HIF primarily affects myoblast differentiation instead. These data are again reminiscent of the function of Wnt signaling in myogenesis. It has been shown that canonical Wnt signaling mediates satellite cell differentiation, whereas non-canonical Wnt signaling regulates the symmetric expansion of satellite cells and myofiber growth (von Maltzahn et al., 2012b). We further demonstrated that HIF inhibits canonical Wnt signaling during muscle regeneration, as reflected in increased Tcf7 and Axin2 expression upon Hif1a depletion in satellite cells (Fig. 3A,B). Multiple Wnt ligands affect myogenic processes, where WNT7A regulates satellite cell expansion and induces myofiber hypertrophy primarily through the non-canonical Wnt axis, including the planar cell polarity or Akt/mTOR pathway (Le Grand et al., 2009; von Maltzahn et al., 2012a). It would be interesting to determine whether HIF1α affects WNT7A or other non-canonical Wnt pathways in this context.

In addition, both Notch and Wnt signaling play pivotal roles in regulating the differentiation of myogenic lineages. Notch is activated during embryonic muscle development and promotes satellite cell division, whereas (canonical) Wnt is induced at a later stage and promotes myogenic differentiation (Luo et al., 2005; Buas and Kadesch, 2010; von Maltzahn et al., 2012b). A proper transition from Notch to Wnt signaling orchestrates developmental programs in muscle stem cells during myogenesis (Brack et al., 2008). Interestingly, Notch has been reported to exhibit crosstalk with the HIF pathway, since hypoxic treatment inhibits myoblast differentiation in a Notch-dependent manner (Gustafsson et al., 2005). This result seems to contradict our observation that HIF1α is dispensable for embryonic myogenesis, as Hif1a deletion in PAX3+ muscle progenitors failed to cause muscle defects in embryos. A possible explanation is that HIF-mediated responses are dose dependent, which has been observed in multiple physiological and pathological settings (Simon and Keith, 2008; Majmundar et al., 2010). For instance, both activation and depletion of Hif2a lead to increased tumor burden in an oncogenic Kras-driven lung cancer model (Kim et al., 2009; Mazumdar et al., 2010b), suggesting that hyperactivation of HIF signaling results in a ‘gain-of-function’ pathway distinct from that engaged upon HIF inactivation. Therefore, HIF is likely to regulate muscle stem cell behavior in a binary manner, whereby hypoxic HIF stimulation inhibits myogenesis via enhanced Notch activity, whereas genetic deletion of HIF accelerates myogenic differentiation by derepressing Wnt.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse models

Animal protocols were approved by U. Penn. I.A.C.U.C. The mice (Mus musculus) were employed and maintained on mixed C57BL/6 and 129 genetic backgrounds: ROSA26 reporter (R26lacZ/+) (Soriano, 1999), Hif1aloxP/loxP (Ryan et al., 2000), ArntloxP/loxP (Tomita et al., 2000), Pax3Cre/+ (Engleka et al., 2005), Ubc-CreERT2 (Ruzankina et al., 2007) and Pax7IresCreER/+ (Nishijo et al., 2009). Non-recombined alleles were designated ‘2L’ and recombined alleles were designated ‘Δ’. Pax3+/+ and Pax3Cre/+Hif1a Δ/+ or Pax3Cre/+ArntΔ/+ embryos exhibited comparable muscle development and were grouped as ‘control’ for Pax3Cre/+Hif1aΔ/Δ or Pax3Cre/+ArntΔ/Δ littermates, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF)

All tissues were harvested, fixed in paraformaldehyde, paraffin embedded and sectioned. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, X-gal staining, IHC for MHC (DSHB; 1:200), PAX7 (DSHB; 1:50), dystrophin (Abcam, ab15277; 1:200) were performed as described (Skuli et al., 2009). IF was performed on tissues using the TSA Kit (Invitrogen) and on cells as described (Majmundar et al., 2012). MHC+ muscle area and PAX7+ progenitor numbers were assessed in embryos as previously described (Vasyutina et al., 2007). Adult EDL muscle transverse sections were taken at the thickest point of the muscle. PAX7+ nuclei per mm2, MYOG+ nuclei per mm2, CNFs per mm2, MHC+ fibers per mm2, percentage of CNF over total fiber area, and average CNF area (mean size of CNF in µm2) were quantified by manual count from six to eight 20× fields (field size: 430 µm×320 µm) of three sections per mouse taken by MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). Van Gieson stain was performed by incubating slides with Weigert's Hematoxylin solution (0.5% Hematoxylin, 2% ferric chloride, 40% ethanol) for 15 min, and then counterstained by using Van Gieson's stain solution (STVGI100, American MasterTech) for 15 min. The von Kossa stain was performed by incubating slides with 5% silver nitrate for 30 min, 5% sodium thiosulfate for 2 min, and then counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (STNFR100, American MasterTech) for 5 min.

Animal handling

Hindlimb ischemia was generated in 8- to 12-week-old mice by FAL, and limb perfusion was measured using diffuse correlation spectroscopy or laser Doppler imaging (Moor Instruments) as described (Mesquita et al., 2010; Skuli et al., 2012). To trigger inducible Cre expression, Tamoxifen (Sigma, T-5684) was dissolved at 20 mg/ml in corn oil. 6- to 8-week-old mice received 10 µl solution per gram body weight for 5 days by oral gavage. When indicated, 20 μl of either DKK1 (50 μg/ml; R&D Systems, 5897-DK-010) or vehicle (PBS) was injected into hindlimb muscles 2 days and 4 days after injury. Muscles were harvested and analyzed 7 days later. Genotyping from ‘skin’ (supplementary material Fig. S2D) was performed on DNA extracted from ∼5 mm×5 mm segments of dorsal skin. Genotyping from ‘myoblasts’ (supplementary material Fig. S2D) was performed on ∼10,000-50,000 primary myoblasts at second passage. Isolation of primary myoblasts from lower limb muscles of 6- to 8-week-old mice was performed as previously described (Springer et al., 2002). Briefly, whole muscle was dissociated in collagenase, washed, and further treated with dispase/collagenase to facilitate detachment of muscle progenitors from muscle fibers. Muscle was then triturated to facilitate the release of muscle progenitors, which were then cultured on collagen-coated plates in F10-based medium as described (Springer et al., 2002).

Cell culture

C2C12 immortalized adult myoblast cells (CRL-1772, ATCC) were cultured as described (Majmundar et al., 2012). Wnt inhibitors used in vitro were 100 ng/ml sFRP3 (592-FR-010, R&D Systems) and 300 ng/ml DKK1.

Molecular biology

Quantitative (q) RT-PCR and western blotting were performed as described (Majmundar et al., 2012) with the following reagents: TaqMan primers (Applied Biosystems) for Myog (Mm00446195_g1), Hif1a (Mm01283758_g1), Pgk1 (Mm00435617_m1), Axin2 (Mm00443610_m1) and Tcf7 (Mm00493445_m1); Ponceau S stain (Sigma); and antibodies against HIF1α (10006421, Cayman; 1:1000) and Actin (pan Ab-5, Thermo Scientific; 1:3000). qRT-PCR results were calculated using the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method, with the murine Rn18s gene employed as the endogenous control (Mm03928990_g1).

Statistics

All results are presented as mean±s.e.m. unless specified otherwise. P-values were calculated based on two-tailed, unpaired Student's t-tests. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Jonathan Epstein and Charles Keller for providing reagents; and Zachary Quinn, Dionysios Giannoukos and Theresa Richardson for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health [grants T32-AR053461-03 to A.J.M. and 5-R01-HL-066310 to M.C.S.] and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (M.C.S.). Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Author contributions

A.J.M., B.L., N.S., A.G.Y. and M.C.S. designed the experiments; A.J.M., B.L., D.S.M.L., N.S., R.C.M., M.N.K. and M.N.-M. performed the experiments; A.J.M., B.L. and M.C.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.123026/-/DC1

References

- Bentzinger C. F., Wang Y. X. and Rudnicki M. A. (2012). Building muscle: molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a008342 10.1101/cshperspect.a008342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borselli C., Storrie H., Benesch-Lee F., Shvartsman D., Cezar C., Lichtman J. W., Vandenburgh H. H. and Mooney D. J. (2010). Functional muscle regeneration with combined delivery of angiogenesis and myogenesis factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3287-3292. 10.1073/pnas.0903875106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Marce M., Okuyama H., Wesley J. B., Sarkar K., Kimura H., Liu Y. V., Zhang H., Strazza M., Rey S., Savino L. et al. (2007). Effects of aging and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activity on angiogenic cell mobilization and recovery of perfusion after limb ischemia. Circ. Res. 101, 1310-1318. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack A. S., Conboy I. M., Conboy M. J., Shen J. and Rando T. A. (2008). A temporal switch from notch to Wnt signaling in muscle stem cells is necessary for normal adult myogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2, 50-59. 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buas M. F. and Kadesch T. (2010). Regulation of skeletal myogenesis by Notch. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 3028-3033. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo A., De Mori R., Martelli F., Pompilio G., Capogrossi M. C. and Germani A. (2004). Hypoxia inhibits myogenic differentiation through accelerated MyoD degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16332-16338. 10.1074/jbc.M313931200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engleka K. A., Gitler A. D., Zhang M., Zhou D. D., High F. A. and Epstein J. A. (2005). Insertion of Cre into the Pax3 locus creates a new allele of Splotch and identifies unexpected Pax3 derivatives. Dev. Biol. 280, 396-406. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber M., Hu C.-J., Johnson R. S., Brown E. J., Keith B. and Simon M. C. (2007). Acute postnatal ablation of Hif-2alpha results in anemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 2301-2306. 10.1073/pnas.0608382104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson M. V., Zheng X., Pereira T., Gradin K., Jin S., Lundkvist J., Ruas J. L., Poellinger L., Lendahl U. and Bondesson M. (2005). Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev. Cell 9, 617-628. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt W. R. (2001). Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1608-1621. 10.1056/NEJM200105243442108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson D. A., Zhao J., Merrell A., Haldar M. and Kardon G. (2009). Embryonic and fetal limb myogenic cells are derived from developmentally distinct progenitors and have different requirements for beta-catenin. Genes Dev. 23, 997-1013. 10.1101/gad.1769009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaidi A., Williams A. C. and Paraskeva C. (2007). Interaction between beta-catenin and HIF-1 promotes cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 210-217. 10.1038/ncb1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. Y., Perera S., Zhou B., Carretero J., Yeh J. J., Heathcote S. A., Jackson A. L., Nikolinakos P., Ospina B., Naumov G. et al. (2009). HIF2alpha cooperates with RAS to promote lung tumorigenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2160-2170. 10.1172/JCI38443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand F., Jones A. E., Seale V., Scimè A. and Rudnicki M. A. (2009). Wnt7a activates the planar cell polarity pathway to drive the symmetric expansion of satellite stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 4, 535-547. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. W., Stabile E., Kinnaird T., Shou M., Devaney J. M., Epstein S. E. and Burnett M. S. (2004). Temporal patterns of gene expression after acute hindlimb ischemia in mice: insights into the genomic program for collateral vessel development. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 474-482. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J.-H., Chun Y.-S. and Park J.-W. (2008). Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha obstructs a Wnt signaling pathway by inhibiting the hARD1-mediated activation of beta-catenin. Cancer Res. 68, 5177-5184. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Wen Y., Bi P., Lai X., Liu X. S., Liu X. and Kuang S. (2012). Hypoxia promotes satellite cell self-renewal and enhances the efficiency of myoblast transplantation. Development 139, 2857-2865. 10.1242/dev.079665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo D., Renault V. M. and Rando T. A. (2005). The regulation of Notch signaling in muscle stem cell activation and postnatal myogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 612-622. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majmundar A. J., Wong W. J. and Simon M. C. (2010). Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell 40, 294-309. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majmundar A. J., Skuli N., Mesquita R. C., Kim M. N., Yodh A. G., Nguyen-McCarty M. and Simon M. C. (2012). O2 regulates skeletal muscle progenitor differentiation through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 36-49. 10.1128/MCB.05857-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar J., O'Brien W. T., Johnson R. S., LaManna J. C., Chavez J. C., Klein P. S. and Simon M. C. (2010a). O2 regulates stem cells through Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1007-1013. 10.1038/ncb2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar J., Hickey M. M., Pant D. K., Durham A. C., Sweet-Cordero A., Vachani A., Jacks T., Chodosh L. A., Kissil J. L., Simon M. C. et al. (2010b). HIF-2alpha deletion promotes Kras-driven lung tumor development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14182-14187. 10.1073/pnas.1001296107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita R. C., Skuli N., Kim M. N., Liang J., Schenkel S., Majmundar A. J., Simon M. C. and Yodh A. G. (2010). Hemodynamic and metabolic diffuse optical monitoring in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia. Biomed. Opt. Express 1, 1173-1187. 10.1364/BOE.1.001173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijo K., Hosoyama T., Bjornson C. R. R., Schaffer B. S., Prajapati S. I., Bahadur A. N., Hansen M. S., Blandford M. C., McCleish A. T., Rubin B. P. et al. (2009). Biomarker system for studying muscle, stem cells, and cancer in vivo. FASEB J. 23, 2681-2690. 10.1096/fj.08-128116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoni N. F., Peale F., Wang F., Errett-Baroncini C., Steinmetz H., Toy K., Bai W., Williams P. M., Bunting S., Gerritsen M. E. et al. (2002). Time course of skeletal muscle repair and gene expression following acute hind limb ischemia in mice. Physiol. Genomics 11, 263-272. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00110.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provot S., Zinyk D., Gunes Y., Kathri R., Le Q., Kronenberg H. M., Johnson R. S., Longaker M. T., Giaccia A. J. and Schipani E. (2007). Hif-1alpha regulates differentiation of limb bud mesenchyme and joint development. J. Cell Biol. 177, 451-464. 10.1083/jcb.200612023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F., Rocancourt D., Mansouri A. and Buckingham M. (2005). A Pax3/Pax7-dependent population of skeletal muscle progenitor cells. Nature 435, 948-953. 10.1038/nature03594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H., Accili D. and Duan C. (2010). Hypoxia converts the myogenic action of insulin-like growth factors into mitogenic action by differentially regulating multiple signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5857-5862. 10.1073/pnas.0909570107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzankina Y., Pinzon-Guzman C., Asare A., Ong T., Pontano L., Cotsarelis G., Zediak V. P., Velez M., Bhandoola A. and Brown E. J. (2007). Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell 1, 113-126. 10.1016/j.stem.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan H. E., Poloni M., McNulty W., Elson D., Gassmann M., Arbeit J. M. and Johnson R. S. (2000). Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is a positive factor in solid tumor growth. Cancer Res. 60, 4010-4015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schipani E., Ryan H. E., Didrickson S., Kobayashi T., Knight M. and Johnson R. S. (2001). Hypoxia in cartilage: HIF-1alpha is essential for chondrocyte growth arrest and survival. Genes Dev. 15, 2865-2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M. C. and Keith B. (2008). The role of oxygen availability in embryonic development and stem cell function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 285-296. 10.1038/nrm2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuli N., Liu L., Runge A., Wang T., Yuan L., Patel S., Iruela-Arispe L., Simon M. C. and Keith B. (2009). Endothelial deletion of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha (HIF-2alpha) alters vascular function and tumor angiogenesis. Blood 114, 469-477. 10.1182/blood-2008-12-193581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuli N., Majmundar A. J., Krock B. L., Mesquita R. C., Mathew L. K., Quinn Z. L., Runge A., Liu L., Kim M. N., Liang J. et al. (2012). Endothelial HIF-2alpha regulates murine pathological angiogenesis and revascularization processes. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1427-1443. 10.1172/JCI57322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. (1999). Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 21, 70-71. 10.1038/5007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer M. L., Rando T. A. and Blau H. M. (2002). Gene delivery to muscle. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. Chapter 13, Unit13 14 10.1002/0471142905.hg1304s31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco F. S., Dellavalle A., Diaz-Manera J., Messina G. and Cossu G. (2010). Repairing skeletal muscle: regenerative potential of skeletal muscle stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 11-19. 10.1172/JCI40373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita S., Sinal C. J., Yim S. H. and Gonzalez F. J. (2000). Conditional disruption of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) gene leads to loss of target gene induction by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1674-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasyutina E., Lenhard D. C., Wende H., Erdmann B., Epstein J. A. and Birchmeier C. (2007). RBP-J (Rbpsuh) is essential to maintain muscle progenitor cells and to generate satellite cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 4443-4448. 10.1073/pnas.0610647104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Maltzahn J., Bentzinger C. F. and Rudnicki M. A. (2012a). Wnt7a–Fzd7 signalling directly activates the Akt/mTOR anabolic growth pathway in skeletal muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 186-191. 10.1038/ncb2404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Maltzahn J., Chang N. C., Bentzinger C. F. and Rudnicki M. A. (2012b). Wnt signaling in myogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 602-609. 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun Z., Lin Q. and Giaccia A. J. (2005). Adaptive myogenesis under hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 3040-3055. 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3040-3055.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.