Abstract

Therapeutic vaccination of patients with cancer-targeting tumor-associated antigens is a promising strategy for the specific eradication of invasive malignancies with minimal toxicity to normal tissues. However, as increasingly potent modalities for stimulating immunologic responses are developed for clinical evaluation, the risk of inflammatory and autoimmune toxicities also may be exacerbated. In this report, we describe the induction of a severe (Grade 3) immunologic reaction in a patient with newly-diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM) receiving autologous RNA-pulsed dendritic cell (DC) vaccines admixed with GM-CSF and administered coordinately with cycles of dose-intensified temozolomide (diTMZ). Shortly after the eighth administration of the admixed intradermal vaccine, the patient experienced dizziness, flushing, conjunctivitis, headache, and the outbreak of a disseminated macular/papular rash and bilateral indurated injection sites. Immunologic work-up of patient reactivity revealed sensitization to the GM-CSF component of the vaccine and the production of high levels of anti-GM-CSF autoantibodies during vaccination. Removal of GM-CSF from the DC vaccine allowed continued vaccination without incident. Despite the known lymphodepletive and immunosuppressive effects of TMZ, these observations demonstrate the capacity for the generation of severe immunologic reactivity in patients with GBM receiving DC-based therapy during adjuvant diTMZ.

Keywords: glioblastoma, dendritic cells, GM-CSF, immunotherapy

Introduction

Immunotherapy is an innovative approach to the treatment of invasive malignancies that holds considerable promise for the development of effective and non-toxic treatment for refractory tumors such as glioblastoma (GBM). Autologous dendritic cell (DC) vaccines are a cellular therapeutic platform that has been deployed in patients with GBM with the aim of the active induction of potent antitumor immunity that spares normal eloquent cortex (1–4). DCs pulsed with GBM tumor antigens in the form of lysates, defined peptides, or antigen-encoding RNAs, have been shown to be safe while inducing immunologic responses and promising antitumor efficacy in early stage clinical studies (5–11). In attempts to potentiate these immune responses, adjuvants such as GM-CSF are often incorporated into vaccine formulations (12, 13). GM-CSF is naturally produced to stimulate white blood cells, and is not expected to precipitate hypersensitivity. Furthermore, autologous DC vaccines have rarely been reported to induce intolerable inflammatory toxicity or autoimmune reactivity in patients receiving intradermal injection of antigen-pulsed DCs. We report the induction of a severe hypersensitivity reaction in a patient with GBM enrolled on a clinical trial evaluating the use of autologous DCs pulsed with human cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp65 RNA and co-injected with recombinant GM-CSF (sargramostim) as an adjuvant. CMV antigens have been reported by several groups to be expressed in GBM tumors and we have demonstrated the relevance of CMV pp65 as an immunologic target in GBM tumors (10, 14–16). This is our first experience of a severe immunologic reaction in a patient receiving autologous DC vaccination, which occurred despite the patient being on continuous cycles of lymphodepletive and myelosuppressive TMZ. These results demonstrate the capacity to induce significant immunologic reactions with repetitive vaccination including hypersensitivities in an immunosuppressed patient population receiving intensive chemotherapy. Clinical work up of this episode demonstrates capacity to rationally evaluate vaccine hypersensitivity in order to minimize subsequent risk in treated patients.

Case Report

This is a 55-year-old white male with newly-diagnosed GBM who underwent left parietal craniotomy resulting in gross total resection (>95% removal of enhancing lesion). One month post-resection, the patient enrolled on a clinical trial evaluating autologous RNA-pulsed DC vaccines plus GM-CSF in patients with newly-diagnosed GBM receiving dose-intensified TMZ (diTMZ) (FDA IND 12839, Duke IRB Pro0006677). Prior to the initiation of chemoradiation therapy, the patient underwent leukapheresis for harvest of peripheral blood leukocytes and generation of autologous RNA-pulsed DC vaccines. The patient received the first cycle of adjuvant TMZ (100 mg/m2/day×21 days per 28-day cycle); on day 22 of the first cycle, he received 3 bi-weekly intradermal DC (2×107 cells) +GM-CSF (800 units) vaccines followed by the second cycle of diTMZ. Thereafter, the patient received monthly 21-day diTMZ cycles and vaccines on day 22 of each cycle. At vaccine #8, the patient received bilateral inguinal region intradermal vaccines as per protocol, but within 2 minutes of vaccine administration, he became flushed and developed conjunctivitis. Additionally, he developed an episode of confusion lasting several minutes, and complained of burning sensations in his left foot and toes. He developed diffuse large hives over his chest, back, and axilla while developing a smaller macular/papular rash in the antecubital fossa of both arms. The patient's upper thigh areas, where the vaccine was administered, developed atypically large erythematous and indurated areas bilaterally measuring approximately 15 mm×10 mm with additional small raised red bumps above and below both injections sites. He described having a frontal headache with tunnel vision, but denied difficulty breathing, diaphoresis, or dizziness. Meanwhile, his electrolytes, liver transaminases and sequential 15 minute vital sign checks remained stable. A CBC drawn just prior to vaccination showed stable counts: hemoglobin of 15.5 g/dL, platelet count of 189×10^9 and a white blood count of 7.8×10^9 with 77% segmented neutrophils, 3% bands, 10% lymphocytes, 4% monocytes and 6% eosinophils (CBC values and manual differentials remained at patient’s baseline during vaccinations). The patient was observed until his hives and confusion resolved within 30 minutes. He was transferred to the hospital for admission, but left against medical advice. The study team remained in contact with the patient via telephone and the following morning the patient stated that his injection site swelling was smaller and his erythematous lesions had resolved.

The adverse reaction was immediately reported to the IRB and FDA as a Grade 3 vaccine-related allergic reaction. The Division of Allergy and Immunology was consulted and a plan for testing the individual components of the vaccine for hypersensitivity was developed in consultation with our study team and under guidance by the IRB and FDA. The vaccine components (GM-CSF and autologous RNA-pulsed DCs) were tested separately in small doses by skin reaction test. Administration of a test dose of GM-CSF resulted in the almost immediate development of localized induration consistent with a positive skin-test reaction. We subsequently performed skin testing using autologous RNA-pulsed DCs alone at the time of the scheduled ninth vaccine. The patient received a test dose of 0.02 mL (1×106 DCs) followed by a dose 0.08 mL (4×106 DCs) an hour later. After tolerating these test doses, he received the remainder of the vaccine (1.5×107; 0.3mL in three separate intradermal injection sites) one hour later. He did not develop any symptoms after receiving the DC vaccine without inclusion of GM-CSF suggesting that the allergic response was restricted to adjuvant GM-CSF. Evaluation of antibodies present in the patient’s serum samples confirmed the detection of IgG, IgE, and IgM antibodies against GM-CSF. Interestingly, the patient developed T-cell responses against pp65 after serial vaccinations that correlated with the development of anti-GM-CSF-specific antibodies; however, the T cells were not reactive to GM-CSF. To verify that he did not develop hypersensitivity against pp65, evaluation for anti-pp65 polyclonal antibodies was performed and they were unchanged over baseline at the time of the reaction. Thus, GM-CSF was implicated in precipitating the patient’s hypersensitivity reaction and was removed from future vaccine preparations. The patient completed the remainder of the vaccine regimen (10 total DC vaccines) without incident.

Methods and Results

ATTAC-GM Protocol

Subjects with newly-diagnosed GBM enrolled on the clinical trial (FDA IND BB-12839; Duke IRB Pro0006677) undergo leukapheresis within 4 weeks of resection for harvest of peripheral blood leukocytes and generation of DCs. Patients then receive radiation therapy (RT) with concurrent temozolomide (TMZ, Merck & Co) at a standard targeted dose of 75 mg/m2/d. Patients then start an initial cycle of TMZ (cycle 1) at a targeted dose of 100mg/m2 for 21 days, two to four weeks after completing RT. DCs (2×107 pp65-LAMP mRNA-loaded mature DCs) suspended in preservative-free saline (Hospira) with 800 units of GM-CSF (sargramostim, Genzyme) are given intradermally divided equally over both inguinal regions in 0.1 mL aliquots. Vaccine #2 and #3 occur at 2-week intervals before patients undergo a second leukapheresis (for immunologic monitoring and further DC generations). The patients are then vaccinated at the end of each TMZ cycle for a total of 10 vaccinations after RT. TMZ is given on days 1–21 with DC vaccines given on day 22–24. Patients are monitored in the clinic for thirty minutes post-immunization for the development of any adverse effects post-vaccine.

Antibody detection by bead assay

Humoral response to GM-CSF was evaluated using a laboratory developed and validated flow cytometric bead-linked detection assay. Briefly, recombinant GM-CSF was immobilized on magnetic beads (Dynal M450 tosylactivated beads) following manufacturer’s directions. Human anti-GM-CSF antibody was captured during a 30 minute incubation of serum with beads. Captured antibody was detected through the binding of a labeled secondary anti-human polyclonal antibody (Jackson Immuno Research, goat anti-human-PE, F(ab’)2 fragment specific for both IgG and IgM, #109-116-127). IgE-specific antibodies were analyzed using a biotinylated mouse anti-IgE monoclonal antibody in conjunction with streptavidin-PE (Southern Biotech, 7100-09M) to detect the bead-captured anti-GM-CSF. Labeled beads were then analyzed on a flow cytometer to determine their mean fluorescent intensity (MFI). To confirm specificity, the capacity to block detection of GM-CSF antibodies in serum by pre-absorption of serum with GM-CSF was evaluated at all time points.

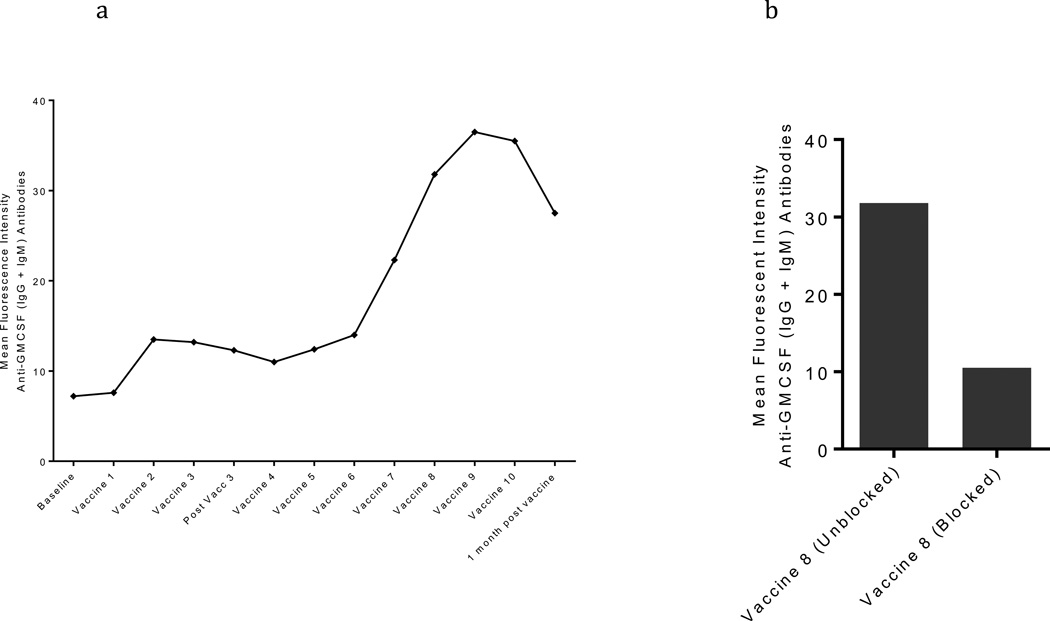

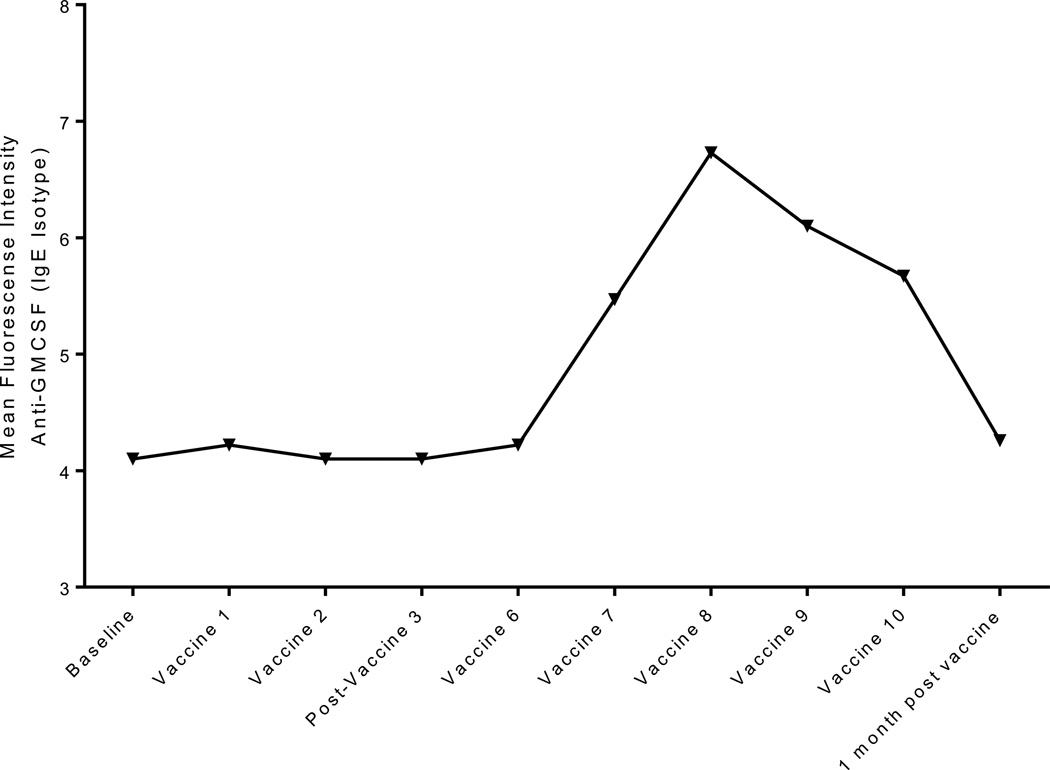

We tested the patient’s serum, obtained before each vaccine, for anti-GM-CSF antibodies as described above. The total antibody response peaks by vaccine #8, coincident with the patient’s hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 1a) verified by competitive inhibition (Figure 1b); the patient’s IgE isotype remains at background levels before peaking at vaccine #8 signifying the development of an IgE-mediated reaction (Figure 2). To verify the presence of anti-GM-CSF IgE antibodies above background levels, competitive blocking experiments of antibody binding were performed as described above.

Figure 1. Detection of Anti-GMCSF polyclonal antibodies.

A) Polyclonal antibody fluorescence index (MFI) against GM-CSF is plotted over time coinciding with vaccine and apheresis administrations. Anti-GM-CSF antibodies (IgG+ IgM) increases over time with repeated vaccinations using recombinant GM-CSF and begin to decrease after the adjuvant is removed.

B) Polyclonal antibody fluorescence index (MFI) against GM-CSF is graphed at vaccine #8 with and without competitive blockade of the polyclonal antibody. Competitive antibody blockade decreases the detection of anti-GM-CSF antibodies as measured by MFI at vaccine #8.

Figure 2. Detection of Anti-GM-CSF IgE antibodies.

IgE antibody fluorescence index (MFI) against GM-CSF is plotted over time coinciding with vaccine and apheresis administrations. IgE antibody fluorescence against GM-CSF peaks at vaccine#8, consistent with the patient’s hypersensitivity reaction at this time point before slowly decreasing back to baseline after adjuvant removal.

ELISPOT Assay

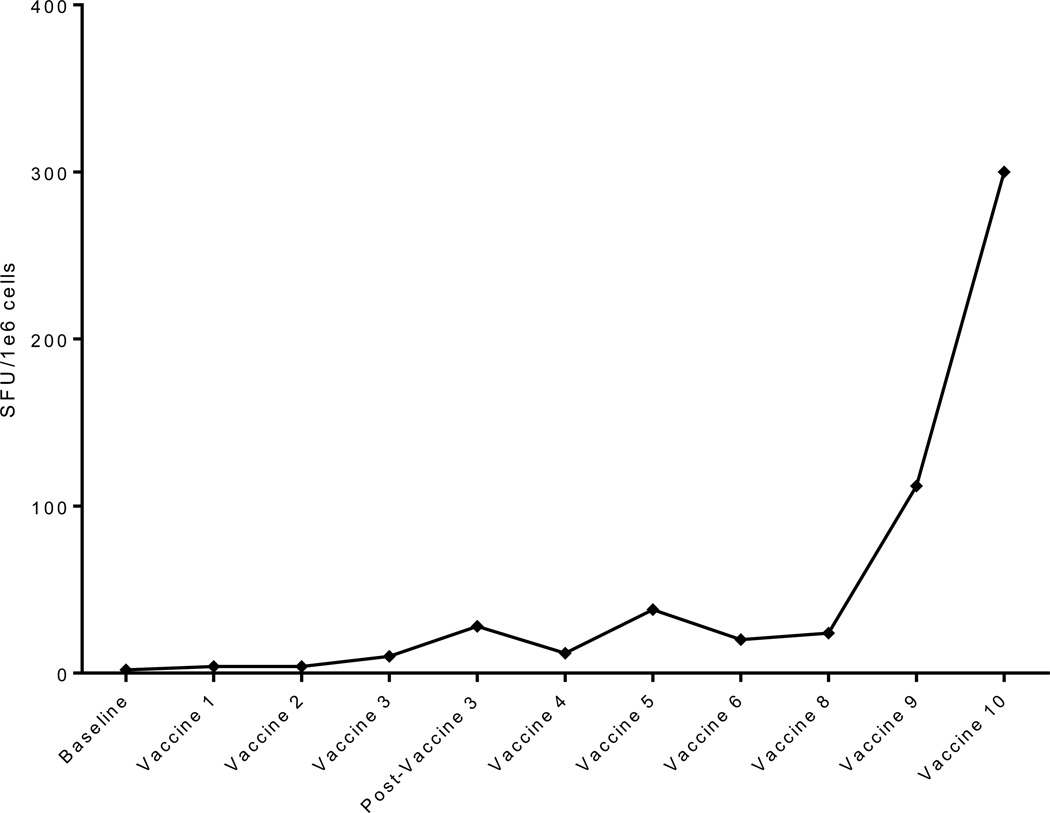

A gamma interferon enzyme-linked immunospot (IFNγ ELISPOT) assay was used to quantify the number of antigen-specific cytokine-secreting T cells using an overlapping CMV peptide pool (gift from Robert Olmsted at Alphavax) as previously published (17). The mean number of spot-forming units (SFU) from duplicate wells, after subtraction of counts from cells cultured with no peptide, was determined. A positive result was determined with replicate control samples to be greater than 10 spots and at least two-fold background with no peptide. This patient demonstrated no detectable pp65-specific immunity at baseline with the induction of a strong de novo antigen-specific response with subsequent vaccinations (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Elispot assay pre- and post-vaccine.

Gamma Interferon Elispot of pp65 peptide pre- and post-vaccine administration. Patient’s gamma interferon response in the presence of pp65 peptide increases steadily with serial vaccinations.

Tetramer analysis

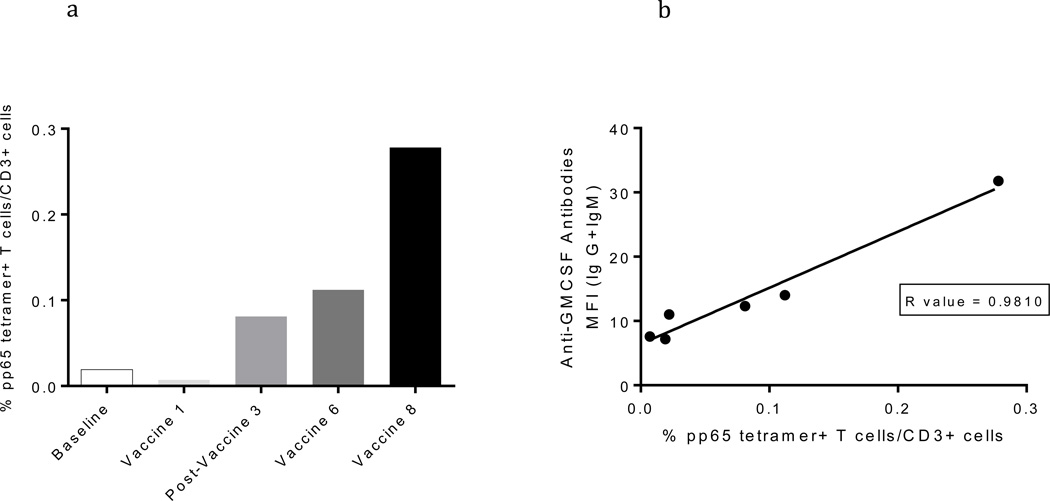

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from patients with GBM were stained for 30 minutes at 2–8°C in the dark with CD8-FITC (BD Bioscience) and CD3-APC (BD Bioscience) in conjunction with PE-conjugated CMVpp65-specific tetramers (Beckman Coulter, HLA-B*0702, HLA-B*3501). Cells were incubated with FACS Lyse (BD Bioscience) for 30 minutes in the dark, washed, and analyzed on BD FACS Calibur. The patient displayed de novo expansion of a CMVpp65-specific T-cell response during vaccination as analyzed by tetramer staining (Figure 4a). There was a strong correlation between the induction of pp65-specific immune response and anti-GM-CSF antibody response in this patient (Figure 4b).

Figure 4. pp65 tetramer-positive T-cell plots.

A) % pp65 tetramer-positive T cells are plotted over time to coincide with vaccine and apheresis times. Tetramer-positive T cells against pp65 increase over time with repeated vaccinations.

Polyclonal antibody (IgG + IgM) fluorescence is plotted over tetramer-positive T cells against pp65. There is a strong positive correlation between anti-GM-CSF antibodies and the generation of antigen-specific T cells against the desired pp65 antigen.

Discussion

Administration of GM-CSF has been associated with constitutional symptoms such as fever and tachycardia, but rarely with type I hypersensitivity reactions (18). Antibodies to GM-CSF have been reported, however, in autoimmune diseases such as those implicated in the pathophysiology of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP), and there are reports of detectable auto-antibodies in normal/healthy patients (19, 20). Healthy patients, however, developed neutralizing antibodies without overt clinical manifestation, while those with PAP developed pulmonary manifestations of decreased alveolar macrophage surfactant clearance (19, 20). Although auto-antibody production is rarely associated with clinical manifestations, there have been incidental case reports of anaphylactoid reactions involved with GM-CSF (21). Meanwhile, although immunotherapeutic interventions have been shown to invoke cellular and humoral immunity via recombinant GM-CSF in clinical trials, these trials refer to neutralizing antibodies without clinical significance (22). In this report, we describe a patient on an immunotherapy trial who presented with clinically significant hypersensitivity reaction after serial administrations of GM-CSF-containing RNA-pulsed DC vaccines. This case not only highlights the serious clinical sequela that may follow serial administrations of GM-CSF, but also demonstrates the potent immunologic induction of auto-antibodies in a lymphodepleted patient with GBM despite receiving dose-intensified TMZ.

The patient received seven intra-dermal injections of DCs per vaccination loaded with RNA encoding the CMV antigen pp65 before developing a hypersensitivity response with vaccine #8. Immune monitoring of response to pp65 vaccination demonstrated the de novo induction and expansion of functional T-cell responses against the targeted antigen concomitant with the development of hypersensitivity to GM-CSF. There are four major types of hypersensitivity reactions. Type I reactions involve antigens cross-linking IgE on pre-sensitized mast cells triggering the release of vasoactive amines such as histamine (23). The reaction develops rapidly after antigen exposure due to pre-formed antibodies and this patient’s history of hives, swelling, and confusion are all suggestive of a possible IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity reaction to vaccine administration (23). Alternatively, type II reactions involve binding of IgG and IgM to host antigens leading to lysis by complement or phagocytosis similar to that in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (24). These reactions are typically more insidious and involve end organs such as joints and kidneys (24). This patient’s skin rash and abrupt onset of symptoms appear inconsistent with a type II reaction. Type III reactions involve antigen-antibody complexes leading to complement activation in serum-sickness and autoimmune illnesses such as systemic lupus erythematosus (23). This immune complex deposition mediates endothelial damage and is often associated with fever and skin rashes (23). Through the duration of this clinical presentation, the patient remained afebrile with expeditious resolution of his symptoms, thus inconsistent with a prototypical type III reaction. Type IV reactions (delayed type hypersensitivity or DTH) involve sensitized T lymphocytes and are typically localized, occurring 48–72 hours after exposure presenting with diffuse skin erythema, induration and blister formation as in contact dermatitis (i.e. poison ivy) and tuberculin skin testing (25). However, given the patient’s abrupt symptom onset with multisystem involvement, delayed hypersensitivity to sargramostim is also inconsistent with this presentation. Additionally, other etiologies of severe immunologic reactions including a systemic cytokine release syndrome (“cytokine storm”) secondary to RNA-pulsed DC vaccination appear unlikely since he previously tolerated vaccine administrations before and after his allergic reaction.

Given the acute onset and constellation of symptoms, this patient’s presentation is consistent with a Type I hypersensitivity reaction secondary to the development of IgE antibodies to GM-CSF. This patient demonstrated immunologic reactivity against the targeted DC vaccine with the induction and expansion of pp65-specific T cells during successive DC vaccination. The positive correlation between his anti-pp65 tetramer frequencies and anti-GM-CSF antibody production further exemplifies that an effective vaccination regimen may be associated with an increased risk of hypersensitivity reactions. However, in our experience administering hundreds of DC vaccines to patients with GBM, this single incident highlighting the risk of hypersensitivity development is an outlier when extrapolated to the remainder of our patient experience. GM-CSF is a frequently used adjuvant in generating immune responses against target cancer antigens and the capacity to develop severe immunologic reactions mediated through breakage of tolerance to this cytokine should be noted. In this regard, screening for induction of anti-GM-CSF antibody development may be warranted for patients receiving repetitive GM-CSF administration with vaccination. In this way, GM-CSF auto-antibodies may be a harbinger for clinical symptomology and immunologic response to vaccination.

In summary, we describe a reported case of type I hypersensitivity to recombinant GM-CSF in a patient with GBM with no previous history of autoimmune disease enrolled on an immunotherapy trial employing the use of autologous DC vaccines. This unusual hypersensitivity reaction after successive administrations with recombinant GM-CSF-containing vaccines not only suggests increased caution in use of this adjuvant, but also highlights the capacity for potent immunologic induction of a response to a “self-antigen” despite administration of lymphodepletive and myelosuppressive dose-intensified TMZ.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Denise Lally-Goss, Beth Perry, Sharon McGehee-Norman, and the faculty and staff of the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center at Duke for assistance with clinical trials management and operations.

Financial Support: This work has been supported by the following NIH/NCI/NINDS grants: 5R01-NS067037 (Mitchell), 5R01-CA134844 (Mitchell), 5P50-CA108786 (Sampson/Bigner), and a CTSA grant UL1RR024128 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Additional support was provided by Accelerate Brain Cancer Cure (ABC2), National Brain Tumor Society, and the American Brain Tumor Association.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: DAM & JHS hold patents related to technologies disclosed in this work. JHS is a consultant for Celldex Therapeutics. JHS receives honoraria from Celldex Therapeutics and funding under the Duke University Faculty Plan from license fees paid to Duke University by Celldex Therapeutics. EJS, ER, RS, PN, AD, AHF, HSF and GA declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: DAM, JHS

Development of Methodology: DAM, ER, RS, GA, JHS

Acquisition of data: ER, RS, PN, AD, AHF

Analysis and interpretation of data: DAM, EJS, ER, RS, JHS

Writing, review, and/or revision of manuscript: DAM, EJS, JHS

Administrative, technical, or material support: DAM, AHF, HSF, JHS

Study supervision: DAM, GA, JHS

References

- 1.Nair SK, Heiser A, Boczkowski D, Majumdar A, Naoe M, Lebkowski JS, et al. Induction of cytotoxic T cell responses and tumor immunity against unrelated tumors using telomerase reverse transcriptase RNA transfected dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2000;6:1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/79519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandramohan V, Mitchell DA, Johnson LA, Sampson JH, Bigner DD. Antibody, T-cell and dendritic cell immunotherapy for malignant brain tumors. Future Oncol. 2013;9:977–990. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson LA, Sampson JH. Immunotherapy approaches for malignant glioma from 2007 to 2009. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell DA, Sampson JH. Toward effective immunotherapy for the treatment of malignant brain tumors. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell DA, Archer G, Bigner D, Friedman H, Lally-Goss D, Perry B, et al. Dendritic Cell Vaccines Targeting Human Cytomegalovirus in Glioblastoma Reveal Lymph Node Homing as a Major Axis for Clinical Intervention. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;14:47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prins RM, Cloughesy TF, Liau LM. Cytomegalovirus immunity after vaccination with autologous glioblastoma lysate. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:539–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0804818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dziurzynski K, Wei J, Qiao W, Hatiboglu MA, Kong LY, Wu A, et al. Glioma-associated cytomegalovirus mediates subversion of the monocyte lineage to a tumor propagating phenotype. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:4642–4649. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang CL, Kandalaft LE, Coukos G. Adjuvants for enhancing the immunogenicity of whole tumor cell vaccines. Int Rev Immunol. 2011;30:150–182. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2011.572210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghazi A, Ashoori A, Hanley PJ, Brawley VS, Shaffer DR, Kew Y, et al. Generation of polyclonal CMV-specific T cells for the adoptive immunotherapy of glioblastoma. J Immunother. 2012;35:159–168. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318247642f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas KG, Bao L, Bruggeman R, Dunham K, Specht C. The detection of CMV pp65 and IE1 in glioblastoma multiforme. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2011;103:231–238. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batich K, Snyder D, Xie WH, Reap E, Archer G, Sampson J, et al. Enhancement of Dendritic Cell Migration to Vaccine-Site Draining Lymph Nodes as a Means to Generate Potent Anti-Tumor Immune Responses. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;14:41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang SN, Choi IK, Huang JH, Yoo JY, Choi KJ, Yun CO. Optimizing DC vaccination by combination with oncolytic adenovirus coexpressing IL-12 and GM-CSF. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2011;19:1558–1568. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eksioglu EA, Kielbasa J, Eisen S, Reddy V. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor increases the proportion of circulating dendritic cells after autologous but not after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:888–896. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.579956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cobbs CS. Cytomegalovirus and brain tumor: epidemiology, biology and therapeutic aspects. Current opinion in oncology. 2013;25:682–688. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair SK, De Leon G, Boczkowski D, Schmittling R, Xie W, Staats J, et al. Recognition and killing of autologous, primary glioblastoma tumor cells by human cytomegalovirus pp65-specific cytotoxic T cells. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang HR, Cordon-Cardo C, Houghton AN, Cheung NK, Brennan MF. Expression of disialogangliosides GD2 and GD3 on human soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 1992;70:633–638. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920801)70:3<633::aid-cncr2820700315>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reap EA, Dryga SA, Morris J, Rivers B, Norberg PK, Olmsted RA, et al. Cellular and humoral immune responses to alphavirus replicon vaccines expressing cytomegalovirus pp65, IE1, and gB proteins. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2007;14:748–755. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00037-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Small EJ, Reese DM, Um B, Whisenant S, Dixon SC, Figg WD. Therapy of advanced prostate cancer with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1999;5:1738–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huizar I, Kavuru MS. Alveolar proteinosis syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15:491–498. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32832ea51c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uchida K, Nakata K, Suzuki T, Luisetti M, Watanabe M, Koch DE, et al. Granulocyte/macrophage-colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies and myeloid cell immune functions in healthy subjects. Blood. 2009;113:2547–2556. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-155689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahar E, Krivoy N, Pollack S. Effective acute desensitization for immediate-type hypersensitivity to human granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;83:543–546. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone HD, Jr, DiPiro C, Davis PC, Meyer CF, Wray BB. Hypersensitivity reactions to Escherichia coli-derived polyethylene glycolated-asparaginase associated with subsequent immediate skin test reactivity to E. coli-derived granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1998;101:429–431. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nigen S, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Drug eruptions: approaching the diagnosis of drug-induced skin diseases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:278–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rive CM, Bourke J, Phillips EJ. Testing for drug hypersensitivity syndromes. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34:15–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posadas SJ, Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions - new concepts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:989–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]