SUMMARY

Our objective was to evaluate recurrence patterns of hypopharyngeal and laryngeal carcinoma after chemoradiation and options for salvage surgery, with special emphasis on elderly patients. In a retrospective study all patients who underwent chemoradiation for hypopharyngeal and laryngeal carcinoma in a tertiary care academic center from 1990 through 2010 were evaluated. Primary outcome measures were the survival and complication rates of patients undergoing salvage surgery, especially in elderly patients. Secondary outcome measures were the predictors for salvage surgery for patients with locoregional recurrence after failed chemoradiotherapy. A review of the literature was performed. Of the 136 included patients, 60 patients had recurrent locoregional disease, of whom 22 underwent salvage surgery. Fifteen patients underwent a total laryngectomy with neck dissection(s) and 7 neck dissection without primary tumour surgery. Independent predictors for salvage surgery within the group of 60 patients with recurrent disease, were age under the median of 59 years (p = 0.036) and larynx vs. hypopharynx (p = 0.002) in multivariate analyses. The complication rate was 68% (14% major and 54% minor), with fistulas in 23% of the patients. Significantly more wound related complications occurred in patients with current excessive alcohol use (p = 0.04). Five-year disease free control rate of 35%, overall survival rate of 27% and disease specific survival rate of 35% were found. For the 38 patients who were not suitable for salvage surgery, median survival was 12 months. Patients in whom the tumour was controlled had a 5-year overall survival of 70%. In patients selected for salvage surgery age was not predictive for complications and survival. In conclusion, at two years follow-up after chemoradiation 40% of the patients were diagnosed with recurrent locoregional disease. One third underwent salvage surgery with 35% 5-year disease specific survival and 14% major complications. Older patients selected for salvage surgery had a similar complication rate and survival as younger patients.

KEY WORDS: Laryngeal cancer, Hypopharyngeal cancer, Salvage surgery, Chemoradiation, Complications, Survival, Elderly, Review

RIASSUNTO

Il nostro obiettivo è stato quello di valutare i pattern di recidiva dei carcinomi della laringe e dell'ipofaringe dopo chemioradioterapia, e le opzioni chirurgiche per un trattamento di salvataggio, con particolare attenzione ai pazienti anziani. Sono stati valutati retrospettivamente tutti i pazienti sottoposti a chemioradioterapia per carcinoma dell'ipofaringe e della laringe dal 1990 al 2010, trattati presso un policlinico universitario. Le principali misure dell'outcome sono state la sopravvivenza e il tasso di complicanze dei pazienti sottoposti a chirurgia di salvataggio. Sono stati valutati i fattori predittivi per la chirurgia di salvataggio nei pazienti con recidiva locoregionale dopo fallimento radiochemioterapico. È stata infine eseguita una revisione della letteratura. Dei 136 pazienti inclusi nello studio, 60 hanno avuto una recidiva locoregionale e 22 di questi sono stati sottoposti a chirurgia di salvataggio. 15 pazienti sono stati sottoposti a una laringectomia totale con svuotamento e 7 pazienti sono stati sottoposti solo a svuotamento laterocervicale. Nel gruppo dei 60 pazienti con recidiva di malattia, i fattori predittivi per la chirurgia di salvataggio emersi all'analisi multivariata sono stati l'età inferiore a 59 anni (p = 0,036) e la localizzazione laringea rispetto a quella ipofaringea (p = 0,002). La percentuale di complicanze registrata è stata del 68% (14% maggiori e 54% minori), con il 23% di fistole. Nei pazienti soggetti ad abuso di sostanze alcoliche si è registrata una maggiore quantità di complicanze relative alla ferita chirurgica (p = 0,04). Il controllo di malattia a 5 anni è stato del 35%, la sopravvivenza è stata del 27% e la sopravvivenza cancro specifica è stata del 35%. La sopravvivenza mediana per i 38 pazienti non sottoponibili a chirurgia di salvataggio è stata di 12 mesi. Per i pazienti nei quali si è ottenuto un controllo di malattia la sopravvivenza a 5 anni è stata del 70%. Per i pazienti sottoposti a chirurgia di salvataggio l'età non ha rappresentato un fattore predittivo né della sopravvivenza né del tasso di complicanze. In conclusione dopo due anni di followup dalla chemioradioterapia è stata diagnosticata una recidiva locoregionale nel 40% dei pazienti. Un terzo è stato sottoposto a chirurgia di salvataggio con una sopravvivenza cancro specifica a 5 anni del 35% e un 14% di complicanze maggiori. I pazienti anziani, selezionati per la chirurgia di salvataggio, hanno avuto un tasso di sopravvivenza e di complicanze maggiori sovrapponibili a quelli dei pazienti più giovani.

Introduction

Treatment of advanced stage squamous cell carcinoma of larynx and hypopharynx constitutes a challenging situation. Cisplatin-based chemoradiation is an established treatment for selected moderately advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma, as it may be organ and function sparing 1-4.

For recurrent disease, salvage laryngectomy or neck dissection may be available as a curative option for selected patients. However, the complication rate of salvage surgery after chemoradiation is relatively high. Wound healing problems are a well-known consequence of surgery in irradiated patients. Fistula rates of 11-58% after salvage laryngectomy are reported 5-11. Due to further locoregional recurrence after salvage laryngectomy, distant metastases, second primaries and other causes, the 5-year overall survival is in the range of 31-57% 12-15. The literature suffers from heterogeneity as to tumour site, previous therapy and salvage therapy.

Herein, we aim to provide insight into the recurrence pattern after chemoradiation for laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma and the options for salvage surgery. We were specifically interested in the complications after salvage surgery, with focus on age. Moreover, the outcome of patients after salvage surgery is evaluated.

Materials and methods

Patients

Sixty patients with locoregional disease after chemoradiation were identified from a database of 136 patients with laryngeal or hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated by chemoradiation with curative intent between January 1990-April 2010. The hospital charts of these patients were retrospectively reviewed. In all patients response to chemoradiation was evaluated within or at 3 months after treatment, unless patients had died during or shortly after the chemoradiation. Resectability prior to treatment was determined by physical examination, imaging and endoscopy. Approval of the Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam was obtained. Patient and treatment characteristics are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Patient characteristics of 60 patients with locoregional disease after chemoradiation.

| Variables | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 51 | 85 |

| Female | 9 | 15 |

| T-stage (prior to chemoradiation) | ||

| T2 | 3 | 5 |

| T3 | 30 | 50 |

| T4 | 27 | 45 |

| N-stage (prior to chemoradiation) | ||

| N0 | 15 | 25 |

| N1 | 7 | 12 |

| N2a | 3 | 5 |

| N2b | 13 | 22 |

| N2c | 17 | 28 |

| N3 | 5 | 8 |

| Primary site | ||

| Hypopharynx | 35 | 58 |

| Larynx | 25 | 42 |

| Operability | ||

| Unresectable | 4 | 7 |

| Organ preservation approach | 56 | 93 |

| Chemoradiation schedule | ||

| Cisplatin IA* | 2 | 3 |

| Cisplatin IV* | 24 | 40 |

| Cisplatin/5-FU alternating** | 14 | 24 |

| Cisplatin/5-FU sequential *** | 13 | 22 |

| Cetuximab**** | 5 | 8 |

| Cetuximab/TPF/Cisplatin or carboplatin***** | 2 | 3 |

Concurrent four intra-arterial cisplatin (150 mg/m2) infusions or three intravenous cisplatin (100 mg/m2) infusions. In both schemes patients were radiatedwith 70 Gy irradiation (6-7 weeks);

cisplatin 20 mg/kg and 5-FU 200 mg/kg intravenously in week 1, 4, 7, 10; radiotherapy in week 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, total dose 60 Gy;

cisplatin 100 mg/kg and 5-FU 1000 mg/kg intravenously, 4 courses; followed by 7 weeks radiotherapy, total dose 70 Gy;

weekly cetuximab in combination with 7 weeks radiotherapy, total dose 70 Gy;

2-4 courses of TPF (Docetaxel, Platinum, Fluorouracil), followed by cisplatin or carboplatin with concurrent 70 Gy radiotherapy (7 weeks), in some patients cetuximab was given during this treatment.

We defined chemoradiation as the combined use of cisplatin based chemotherapy and/or targeted therapy and radiotherapy for the primary treatment. Different schemes are used. Fourteen patients were treated according to an alternating scheme (cisplatin 20 mg/kg and 5-FU 200 mg/kg (i.v.) in week 1, 4, 7 and 10; radiotherapy in week 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 9, total dose 60 Gy) and 13 according to a sequential scheme (cisplatin 100 mg/kg and 5-FU 1000 mg/kg i.v., 4 courses; followed by 7 weeks radiotherapy, total dose 70 Gy). Twenty-four patients were treated with concomitant intravenous administration of 3 × 100 mg/m2 cisplatin on day 1, 22 and 43 with simultaneous radiotherapy. Two patients were treated according to the intra-arterial chemoradiation schedule consisting of four consecutive weekly selective intra-arterial infusions of cisplatin (150 mg/m2) followed by intravenous sodium thiosulphate rescue combined with simultaneous radiotherapy. All patients were irradiated daily for 6-7 weeks to a total dose of 70 Gy (2 Gy per fraction, 5-6/week). Two patients were treated according to the concomitant intravenous cisplatin protocol, in combination with cetuximab. Five patients received weekly cetuximab (loading dose 400 mg/m2, followed by weekly 250 mg/m2) with daily radiotherapy for 7 weeks to a total dose of 70 Gy. Both sides of the neck were radiated in all patients, regardless of the lymph node status.

Definitions

Postoperative complications were categorised into surgical complications (fistula, infection, necrosis, haemorrhage and chyle leakage), pneumonia and other complications (e.g. spondylodiscitis). Complications were classified as major if they required re-operation.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 15.0. Survival rates were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method, with follow-up intervals calculated from the date of salvage surgery. Univariate analysis of survival parameters was done using the log-rank test. Univariate analyses of complication patterns were assessed by utilizing the χ2-test or the independent- samples T-test whenever applicable. Multivariate analysis of survival was performed with Cox regression. A model developed by Tan et al. 16 with stratification factors for survival, was applied to our population.

Results

After a median follow-up of 25 months (range 0-130 months), 60 patients (44%) had presented with recurrent disease. One-third of the patients with recurrent disease (n = 22) underwent salvage surgery for local, regional or locoregional disease. This is 16% of the total group of patients initially treated by chemoradiation. Twenty-four percent of patients with laryngeal carcinoma vs. 10% of patients with hypopharyngeal carcinoma underwent salvage surgery. Two-thirds of patients (n = 38) were not suitable for salvage surgery because of distant metastases (n = 30), poor general condition of the patient (n = 3), refusal of surgery by the patient (n = 1) or unresectability of the tumour (n = 4).

Of the 6 patients with an initial unresectable tumour, 4 patients developed recurrent disease, which was not statistically different from the organ preservation (initial resectable) group. Two patients developed distant metastases and 2 patients were diagnosed with persistent unresectable local disease. Independent predictors for salvage surgery within the group of 60 patients with recurrent disease, were age younger than 59 years (p = 0.036) and larynx vs. hypopharynx (p = 0.002) in multivariate analyses. Gender, Tand N-stage were not associated with surgery for salvage.

The median interval between radiotherapy and recurrence for the 22 patients was 4 months.

The study population consisted of 19 males and 3 females with a median age of 59 years (range: 40-69 years), with primary tumours in larynx (n = 15) and hypopharynx (n = 7) (Table II).

Table II.

Patient and salvage surgery characteristics.

| Patient | Gender | Age | T | N | Site | Recurrence | Larynx | ND* | Reconstruction | Subsequent reconstruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 52 | 4 | 1 | Hypopharynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | FRFF+PM | PM |

| 2 | M | 57 | 3 | 2b | Larynx | Regional | - | Unilateral | PC | |

| 3 | M | 64 | 4 | 0 | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Unilateral | PM | |

| 4 | M | 63 | 4 | 0 | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | PM |

| 5 | M | 62 | 4 | 0 | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Unilateral | PM | |

| 6 | M | 59 | 3 | 2c | Hypopharynx | Regional | - | Bilateral | PM | |

| 7 | M | 41 | 3 | 0 | Hypopharynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Unilateral | PM | |

| 8 | M | 55 | 4 | 2c | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 9 | M | 67 | 4 | 0 | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 10 | M | 57 | 3 | 2b | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 11 | M | 52 | 4 | 3 | Hypopharynx | Regional | - | Unilateral | PM | |

| 12 | M | 49 | 3 | 2a | Larynx | Regional | - | Unilateral | PC | $ |

| 13 | M | 54 | 4 | 2c | Larynx | Locoregional | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PC | |

| 14 | M | 58 | 2 | 2b | Hypopharynx | Regional | - | Unilateral | PC | |

| 15 | M | 53 | 3 | 2c | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 16 | M | 55 | 3 | 0 | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 17 | M | 61 | 3 | 2c | Hypopharynx | Regional | - | Unilateral | PM | |

| 18 | F | 59 | 3 | 0 | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 19 | M | 69 | 4 | 0 | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 20 | F | 67 | 3 | 1 | Larynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 21 | M | 58 | 4 | 3 | Hypopharynx | Local | Laryngectomy | Bilateral | PM | |

| 22 | M | 64 | 3 | 2c | Larynx | Regional | - | Unilateral | PM |

1 year after ND: total salvage laryngectomy with FRFF and PM, followed by a second PM for complications. ND: neck dissection; PC: primary closed; PM: pectoralis major flap; FRFF: free radial forearm flap.

Neck dissection was performed in all patients. In 15 patients the salvage operation consisted of a total laryngectomy with unilateral (n = 2) or bilateral (n = 13) neck dissection. In 7 patients the surgery was limited to a neck dissection because the primary was controlled.

Histopathological examination of total laryngectomy with neck dissection showed negative resection margins in 11 patients (74%), close margins in 2 patients (13%) and microscopic positive margins in 2 patients (13%). Of the patients with neck dissection without laryngectomy 6 had negative resection margins (86%) and 1 microscopic positive margins (14%). No difference in histopathological results between the larynx and hypopharynx was found. Of the two patients with positive margins one was treated with postoperative radiotherapy, but he developed a local recurrence for which he received palliative chemotherapy. One of the patients with close margins developed a recurrence at the stoma and oesophagus, and underwent palliative radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Reconstruction

The pectoralis major myocutaneous or myofascial pectoralis major (PM) flap was the most often used flap after total laryngectomy with or without pharyngectomy. Primary closure was only possible with smaller defects. With larger defects, when between one-third and three-quarters of the pharyngeal circumference has been resected, reconstruction was performed by utilising a pectoralis major myocutaneous PM flap. A circumferential pharyngeal defect not extending into the chest was free radial forearm flap (FRFF). A myofascial PM flap was also used to reinforce pharyngeal defects 17. The mucosal defect was closed primarily in 9 of the 15 patients (60%), reconstructed with a PM flap in 5 patients, and reconstructed with a free radial forearm flap (FRFF) in 1 patient. A PM flap to prevent wound healing problems was used in 9 of the 15 patients with a total laryngectomy and in 4 of the 7 patients with a neck dissection without laryngectomy.

Postoperative complications

No perioperative death occurred. Postoperative complications were observed in 15 (68%) of the 22 patients (Table III). Three patients experienced major complications that required re-operation. This concerned fistula in two patients and a bleeding in one patient that were closed with a (second) PM flap during re-operation. Most of the complications concerned wound healing problems (n = 13; 59%), as fistula (n = 5), wound dehiscence or wound infection (n = 7) or haemorrhage (n = 1). Other complications were pneumonia and spondylodiscitis in 2 patients.

Table III.

Postoperative complications for the total salvage surgery group, the group with an opened pharynx vs. the group with a closed pharynx.

| Complications | Total | Pharynx open | Pharynx closed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| None | 7 | 31% | 4 | 27% | 3 | 43% |

| Wound healing | 13 | 59% | 9 | 59% | 4 | 57% |

| - Infection or dehiscence | 7 | 31% | 5 | 32% | 2 | 29% |

| - Haemorrhage | 1 | 5% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 14% |

| - Fistula | 5 | 23% | 4 | 27% | 1 | 14% |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 5% | 1 | 7% | 0 | 0% |

| Other | 1 | 5% | 1 | 7% | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 22 | 100% | 15 | 100% | 7 | 100% |

Univariate analysis showed significantly more wound healing problems in patients with excessive alcohol intake (8 of 16 patients (50%) vs. none of 5 patients, p = 0.04). Furthermore, none of the following parameters were predictive for the development of postoperative complications: tobacco use or excessive alcohol intake at the time of presentation for the primary tumour, T- or N-stage, site of the primary tumour and age under the median of 59 years. No significant reduction in overall complications, wound related complications or fistula was found in our group of patients with a PM flap after neck dissection compared to patients with a primarily closed neck dissection.

Survival

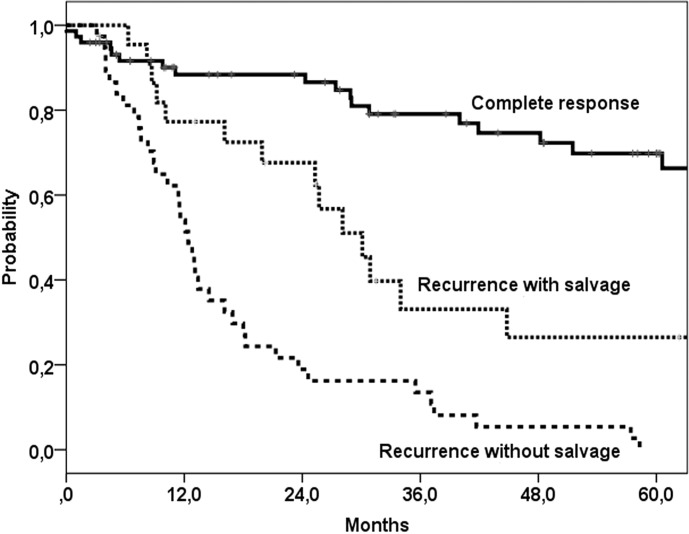

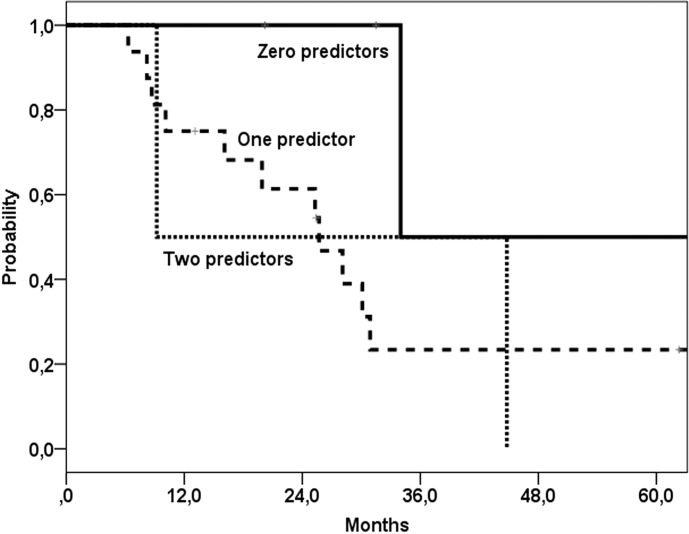

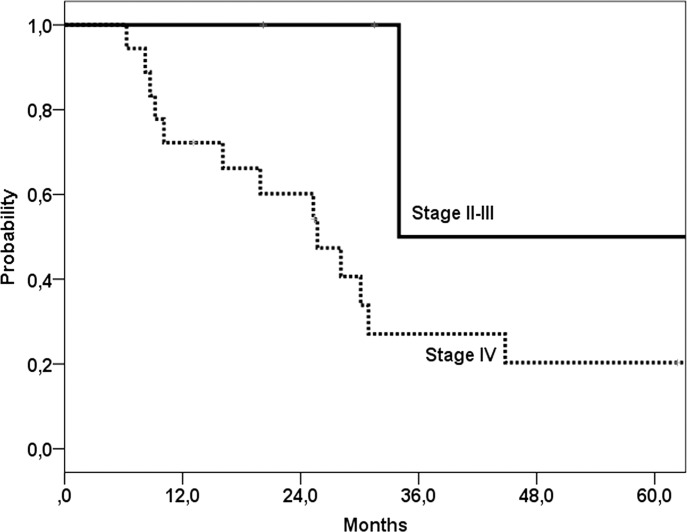

Overall, 5-year disease free control rate was 35%, with 5-year locoregional and distant metastases control rates of 54% and 77%, respectively. Five-year overall survival was 27% (median 30 months) (Fig. 1), and disease specific survival was 35% after salvage surgery. For the 38 patients with residual or recurrent disease after chemoradiation who were not suitable for salvage surgery median survival was 12 months. Patients with tumour control (n = 76) had a 5-year survival of 70% (median 96 months) (Fig. 1). In uni- and multivariate analyses no significant predictors for overall survival after salvage surgery were found. Thus, age under or above the median 60 years was not a predictor factor for survival. The model of Tan et al. 16 stratified patients with none, one or two of the following predictors for post salvage overall survival: stage IV (vs. other stages) and simultaneous (vs. local or regional) failure. When this model was applied to our population, no significant differences between the groups could be found (Fig. 2), although the group with stage IV disease showed a worse overall survival compared to patients with stage II or III disease (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Five-year survival after the last treatment (chemoradiation or salvage surgery).

Fig. 2.

Survival after salvage surgery with model according to Tan et al. 16 Comparison between patients with zero, one or two of the following presalvage predictors: stage IV vs. other stages and simultaneous locoregional vs. local or regional failure. No significant difference between the three groups was found.

Fig. 3.

Survival after salvage surgery with model according to Tan et al. 16 Comparison between patients initial stage IV vs. initial non-stage IV disease. A trend (p = 0.05) towards a worse survival for patients with initial stage IV disease was found.

With a median length of follow-up after salvage surgery of 26 months (range 6-127 months), recurrent disease was found in 12 of the 22 patients (64%). These recurrences included local and/or regional recurrences in 8 patients and distant metastases in 4 patients. Local recurrences, regional recurrences and distant metastasis developed after a median interval of 6.5 months (range 2.5-14.3), 7.5 months (range 4.4-14,3) and 3.7 months (range 0-28.2) after salvage surgery, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, 37% of the patients with local and/or regional recurrences after chemoradiation for a laryngeal or hypopharyngeal tumour underwent salvage surgery, which is similar to rates reported by other authors, 33-66% 7 14 16 18. A larger proportion of patients with recurrent laryngeal than hypopharyngeal tumours underwent salvage surgery. This is in accordance with the report by Esteller et al. 18 Independent predictors for salvage surgery within in the group of patients with locoregional failure, were age less than 59 year and larynx primary (vs. hypopharynx).

Fifteen patients underwent laryngectomy with neck dissection and 7 patients neck dissection only.

The rates of complications after salvage surgery are known to be high, with wound related complications and especially pharyngocutaneous fistula as a major problem. In this study 23% of patients developed a fistula. Review of the literature shows complication rates of 5-78%, with fistula in 4-73% of the patients (Table IV). Studies are difficult to compare, because of lack of homogeneity in patients (tumour site, stage) and in primary treatment (radiotherapy, chemoradiation).

Table IV.

Previous studies on complications and survival outcome in patients with salvage surgery after chemoradiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx and larynx.

| Authors | Year | N | Site | Comp | Fistula | LR | OS | DSS | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stoeckli 7 | 2000 | 36 | L | 28% | 14% | 63% (5 y) | RT and CRT | ||

| Stoeckli 7 | 2000 | 9 | H | 40% | 11% | 20% (5 y) | RT and CRT | ||

| Leon 14 | 2001 | 28 | L | 21% | 17% | 57% (5 y) | endoresection | ||

| Weber 35 | 2003 | 75 | L | ~59% | ~30% | 74% (2 y) | 69-71% (2 y) | ||

| Ganly 26 | 2005 | 38 | L | 53% | 32% | ||||

| Clark 13 | 2006 | 138 | L/H | 70% (salvage) |

31% | 31% (5 y) (salvage) |

PT: none, RT, CRT | ||

| Fung 20 | 2007 | 14 | L | 29% | Interposition graft. ngopharyngectomy defects |

||||

| Furuta 44 | 2008 | 34 | L | 47% wound | 24% | ||||

| Gil 5 | 2009 | 18 | L | 39% | PL/TL, RT and CRT | ||||

| Patel 6 | 2009 | 17 | L | 24% | CRT or RT? | ||||

| Relic 45 | 2009 | 16 | L/H | 73% | 38% (3 y) | 1 PL | |||

| Tsou 8 | 2010 | 48 | H | 58% | |||||

| Paleri* 46 | 2011 | >350 | L | 87% (2 y) | 83% (3 y) | 91% (2 y) | RT and CRT, PL | ||

| vd Putten 15 | 2011 | 120 | L | 70% (5 y) 79% (5 y) regional |

50% (5 y) | 58% (5 y) | RT and CRT, TL | ||

| Klozar 47 | 2012 | 208 | L/H | 34% | RT and CRT | ||||

| Sewnaik 48 | 2012 | 24 | L/H | 92% | |||||

| Patel 9 | 2013 | 359 | L/H | 27% | RT and CRT, primLE | ||||

| Li 12 | 2013 | 100 | L | 70% (5 y) | 55-70% (5 y) | RT and CRT, survival | |||

| Basheeth 49 | 2013 | 45 | L/H | 44% | Major complications, N0 | ||||

| Suzuki 50 | 2013 | 24 | H | 33% | 50% (2 y) | ||||

| Sayles* 10 | 2014 | 33 st | L/H | 34% | |||||

| Timmermans 31 | 2014 | 98 | L/H | 26% | RT and CRT, primLE | ||||

| Omura 51 | 2014 | 42 | H | 40% (3 y) | RT and CRT, ICT | ||||

| Powell 52 | 2014 | 45 | L/H | 22% | |||||

| Suslu 11 | 2015 | 151 | L/H | 13% | RT and CRT, ICT | ||||

| Sassler 30 | 1995 | 18 | HN | 61% major | 50% | Sequential CRT | |||

| Newman 53 | 1997 | 17 | HN | 35% | 20% | ||||

| Lavertu 34 | 1998 | 26 | HN | 46% | 4% | ||||

| Goodwin 37 | 2000 | 109 | HN | 20% | 6% | Med 21.5 months | PT: surgery, RT, CRT (17%) | ||

| Goodwin* 37 | 2000 | 1633 | HN | 39% | 39% (5 y) | PT: surgery, RT, CRT | |||

| Agra 54 | 2003 | 124 | HN | 78% (CRT) | PT: surgery, RT, CRT | ||||

| Gleich 55 | 2004 | 48 | HN | 20% (5 y) | 15% (5 y) | Local recurrence | |||

| Taussky 56 | 2005 | 17 | HN N |

76% | 24% | 46% (3 y) 13% (5 y) |

RT and CRT | ||

| Morgan 57 | 2007 | 38 | HN | 11% | 5% | Local compl 23% | |||

| Encinas 58 | 2007 | 26 | HN | 31% | Article not available | ||||

| Richey 39 | 2007 | 38 | HN | 24% | 42% (2 y) | 27-60% (1,2 y) |

|||

| Tan 16 | 2010 | 38 | HN | 63% | 43% (2 y) 37% (5 y) |

||||

| Inohara 36 | 2010 | 30 | HN | 30% | 7% | 74-87% (3 y) | |||

| Esteller 18 | 2011 | 32 | HN | 28% | 19% | 34% (5 y) | |||

| Simon 59 | 2011 | 21 | HN | 33% | 10% | ||||

| Leon 60 | 2015 | 24 | HN | 63% 13% |

26%(5 y) 70%(5 y) |

CRT Bioradiotherapy |

|||

| Present study | 22 | HN | 73% | 23% | 58% (5 y) | 27% (5 y) | 36% (5 y) | ||

| Davidson 27 | 1999 | 34 | N | 38% | 12% | 37% CRT | |||

| Stenson 61 | 2000 | 69 | N | 25% | 10% | ||||

| Newkirk 62 | 2001 | 33 | N | 13 CRT,20 RT. | |||||

| Grabenbauer 63 | 2003 | 56 | N | 25% | 4% | 44%(5 y) | 55% | Planned ND | |

| Kutler 64 | 2004 | N | ~30% | Only abstract | |||||

| Brizel 65 | 2004 | 52 | N | 8% major | 75% (4 y) | 77%(4 y) | Planned ND in N2-3. survival cCR | ||

| Frank 66 | 2005 | 39 | N | 5% surgical | |||||

| vd Putten 67 | 2007 | 61 | N | 79% (5 y) | 36% (5 y) | ||||

| Nouraei 68 | 2008 | 41 | N | 95% (5 y) | 64% (5 y) | Survival hemineck | |||

| Vedrine 69 | 2008 | 28 | N | 14% severe | |||||

| Christopoulos 70 | 2008 | 32 | N | 13% | |||||

| Lango 71 | 2009 | 65 | N | 18% | 5% | 55%CRT | |||

| Relic 45 | 2009 | 12 | N | 8% | |||||

| Hillel 72 | 2009 | 41 | N | 17% | |||||

| Bremke 73 | 2009 | 25 | N | 24% | |||||

| Goguen 28 | 2010 | 105 | N | 37% | |||||

| Robbins 74 | 2012 | 30 | N | 60% (5 y) | SSND, CRT | ||||

| Yirbesoglu 75 | 2013 | 44 | N | 71-73% (3 y) | 55-64% (3 y) |

Systematic review;

y: year; Com: complications, fistul: fistula, LR: locoregional control rate, OS: overall survival, DSS: disease specific survival, L: larynx, H: hypopharynx, HN: head and neck, N: neck, y: year, DFS: disease free survival, CRT: chemoradiotherapy, RT: radiotherapy, CT: chemotherapy, ND: neck dissection, PT: previous treatment, PL: partial laryngectomy, TL: total laryngectomy, primLE: primary laryngectomy, SSND: super selective neck dissection, st: studies, ICT: induction chemotherapy.

If wound healing problems are likely, pedicled PM flaps are very useful to cover important structures in the neck with well vascularised, non-irradiated tissue. In the present study, in 59% of the patients a PM flap was used for prevention of wound related complications. Unfortunately, no significant reduction in overall complications, wound related complications or fistula was found in our group of patients with a PM flap after neck dissection compared to patients with a primarily closed neck dissection. In our population only patients with considerable postradiation effects who were considered to be prone to wound healing problems underwent reconstruction with PM flap in the neck. Most studies evaluating reconstructive methods are conducted in patients undergoing salvage laryngectomy (Table V). Similar to our results, no difference in the incidence of local wound complications or fistula between the groups with and without PM flap was found by Gil et al. 5 and Righini et al. 19 Although it was an effective technique to prevent major complications, free vascularised tissue reinforcement did not alter the overall fistula rate as compared to when no flap was used, as reported by Fung et al. 20 Smith et al. 21 reported a significant reduction in fistula formation in patients with as compared to patients without PM flap reconstruction, but the percentage of patients with initial chemoradiation vs. primary surgery was not described. Sayles et al. 10 performed a review and meta- analysis of 33 studies, and found only 10% fistula for salvage laryngectomy with onlay flap-reinforced closure compared to 28% fistula for salvage laryngectomy when no flap was used. Recently Paleri et al. 22 described in a systematic review of nearly 600 patients a reduced risk of fistula by one-third in patients who have flap reconstruction/ reinforcement. Reconstruction of the mucosal defect using a PM flap may be associated with a higher rate of fistulae as compared to primary closure whereas a PM flap used as layer between mucosa and skin may reduce the risk of fistula formation. According to Righini et al. 19, fistula formation in postradiotherapy salvage surgery was reduced from 73% to 13% when a flap was used in the subgroup of patients with diabetes mellitus, a history of vascular disease or a poor nutritional status. Tsoe et al. 8 and Withrow et al. 23 suggest to reconstruct laryngectomy defects with an ALT (anterolateral thigh) or FRFF flap, as the incidence of fistula was low in their study.

Table V.

Comparison of pharyngocutaneous fistula in patients with salvage laryngectomy with and without flap reinforcement. In two studies, besides for reinforcement, the flap was also used to reconstruct pharyngeal defects 21 23.

| Authors | Year | N | Site | Flap | Fistula | WC | Fistula No flap | WC No flap | p | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Righini 19 | 2005 | 60 | larynx larynx |

PMMF PMMF |

23% 13% |

50% 73% |

0.06 0.018 |

Radiotherapy Subgroup: diabetes mellitus, vascular history, poor nutritional status |

||

| Fung 20 | 2007 | 41 | larynx | FVT | 29% | 0% | 30% | 15% | n.s. | |

| Patel 6 | 2009 | 17 | larynx | PMF | 0% | 57% | 0.02 | (Chemo)radiotherapy | ||

| Gil 5 | 2009 | 80 | larynx | PMMF | 27% | 24% | n.s. | PMMF 64% CRT, nonPMMF 25% CRT | ||

| Smith 21 | 2003 | 223 | larynx | PMF | <1% | 23% | ||||

| Withrow 23 | 2007 | 37 | larynx | FRFF | 18% | 50% | FRFF 41%CRT, nonFRFF 35%CRT | |||

| Patel 9 | 2013 | 359 | larynx | PMF FVT |

15% 25% |

34% | 0.02 0.07 |

(Chemo)radiotherapy | ||

| Powell 52 | 2014 | 45 | larynx | FVT/PMF | 0% | 26% | ||||

| Sayles* 10 | 2014 | 33 studies | larynx | Onlay flap | 10% | 28% | 0.001 | (Chemo)radiotherapy | ||

| Paleri* 22 | 2014 | 591 | larynx | Pooled relative risk 0.63 (reduction one third compared to no flap) |

Systematic review;

WC: wound complications, p: p-value, PMMF: pectoralis major myofascial flap, FVT: free vascularised tissue, PMF: pectoralis major flap, FRFF: free radial forearm flap, CRT: chemoradiotherapy.

Besides hypoalbuminaemia, neck dissection, comorbidities with diabetes mellitus or ischaemic heart disease, Tsoe et al. 8 found that reconstruction of the pharynx with primary closure had a statistically significant increased rate of fistula formation. On the contrary, Shemen et al. 24 and Herranz et al. 25 found an increase in complication rate when flap reconstruction was required. These patients had no history of radiation, and probably had a greater defect when a flap was required. Ganly et al. 26 found no association between wound complications and flap reconstruction or neck dissection. The only significant independent predictor found was chemoradiation. Other suggested potential predictors for increased wound complications and fistula are: postoperative haemoglobin level lower than 12.5 g/dl, albumin level less than 40 g/l, prior tracheotomy, preoperative radio- an/or chemotherapy, concurrent neck dissection, radical neck dissection, poor nutritional status, tobacco and excessive alcohol use, poor renal and hepatic function, radiotherapy doses in excess of 70 Gy, early removal of drains (within 3 days of operation), vacuum drain duration and surgery extended to the pharynx or hypopharynx cancer 11 27-31. We found more wound related complications in patients with current excessive alcohol use. This might be caused by immunosuppression due to ethanol, or alcohol-related lifestyle factors such as certain dietary deficiencies owing to unevenly composed diets 32.

Whether the interval between chemoradiotherapy and salvage surgery influences the risk of fistula formation remains uncertain. Increased incidence of wound complications was reported when the interval was shorter 23 25 33. However, Lavertu et al. 34 and Weber et al. 35 found no significant difference between groups with short and longer interval between chemoradiation and salvage surgery. Inohara et al. 36 found no difference in complication incidence between salvage surgery for persistent or recurrent disease. We also did not find an association between interval and complication rate.

Comparing our results in patients with salvage laryngectomy: a) after previous radiotherapy in a previous study 15; to b) after previous chemoradiotherapy in the present study, shows a worse 5-year prognosis for local disease control (58% vs. 70%) and overall survival (27% vs. 50%) in the chemoradiotherapy group. The total complication rate is 73% after chemoradiotherapy vs. 56% after radiotherapy.

The 5-year overall survival of 27% is comparable to other series, with a relatively better survival for patients with recurrent laryngeal carcinoma (compared to hypopharyngeal) or patients with a regional recurrence (Table IV). Even after adjusting for covariates, Goodwin 37 found that a history of chemotherapy was associated with poorer survival after salvage surgery, suggesting a more aggressive tumour biology 38. Because of the low survival and high complication rates, the profit of salvage surgery is sometimes questioned. Salvage surgery is definitely worthwhile in a subset of patients. Reliable predictors for survival after salvage surgery are needed. Tan et al. 16 suggested a model with stage IV tumours and concurrent local and regional failures as independent negative predictors. Esteller et al. 18 found no significant differences in survival when analysed according to the classification of Tan. We found a worse survival for stage IV initial tumours. Other suggested potential predictors for a worse survival are: residual disease, older age, N3, positive resection margins and neck nodes with extranodal spread 18 38 39.

In this series age was an independent predictor for salvage surgery. Older patients were less frequently candidate for salvage surgery if recurrent tumour was diagnosed. Elderly patients with head and neck cancer generally have multiple and more severe comorbidity 40. Comorbidity is associated with a higher complication rate and poorer survival after major surgery 41-43. Selection of elderly patients based on comorbidity seems to be the explanation for the similar complication rate and survival after salvage surgery. Moreover, patients with severe comorbidity would not have been treated with chemoradiation in the first place and therefore not included in this study.

In conclusion, one third of the patients with local and/or regional disease after chemoradiation underwent salvage surgery. Most of the patients not suitable for salvage surgery had distant metastases. Forty percent of the laryngectomies needed a flap reconstruction to cover mucosal defects. Patients who were at forehand more prone to wound healing failures underwent reconstruction with a PM flap in the neck to prevent wound related complications. One in four patients developed a pharyngocutaneous fistula. Only current excessive alcohol use was associated with complications. No significant independent predictors of survival were identified. The 5-year overall survival rate was 27% after salvage surgery. Older patients with recurrent laryngeal or hypopharyngeal carcinoma after chemoradiation selected for salvage surgery have a similar complication and survival rate compared to younger patients.

Acknowledgement

The authors like to thank Dr. Annalisa M. Lo Galbo for translation in Italian.

References

- 1.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf GT, Hong WK. Induction chemotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer: is there a role? Head Neck. 1995;17:279–283. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880170402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, et al. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: preliminary results of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:890–899. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.13.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefebvre JL, Rolland F, Tesselaar M, et al. Phase 3 randomized trial on larynx preservation comparing sequential vs alternating chemotherapy and radiotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:142–152. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gil Z, Gupta A, Kummer B, et al. The role of pectoralis major muscle flap in salvage total laryngectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:1019–1023. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel UA, Keni SP. Pectoralis myofascial flap during salvage laryngectomy prevents pharyngocutaneous fistula. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoeckli SJ, Pawlik AB, Lipp M, et al. Salvage surgery after failure of nonsurgical therapy for carcinoma of the larynx and hypopharynx. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:1473–1477. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.12.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsou YA, Hua CH, Lin, et al. Comparison of pharyngocutaneous fistula between patients followed by primary laryngopharyngectomy and salvage laryngopharyngectomy for advanced hypopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2010;32:1494–1500. doi: 10.1002/hed.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel UA, Moore BA, Wax M, et al. Impact of pharyngeal closure technique on fistula after salvage laryngectomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:1156–1162. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayles M, Grant DG. Preventing pharyngo-cutaneous fistula in total laryngectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1150–1163. doi: 10.1002/lary.24448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Süslü N, Senirli RT, Günaydın RÖ, et al. Pharyngocutaneous fistula after salvage laryngectomy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;11:1–7. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2015.1009639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Lorenz RR, Khan MJ, et al. Salvage laryngectomy in patients with recurrent laryngeal cancer in the setting of nonoperative treatment failure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149:245–251. doi: 10.1177/0194599813486257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark JR, Almeida J, Gilbert R, et al. Primary and salvage (hypo)pharyngectomy: Analysis and outcome. Head Neck. 2006;28:671–677. doi: 10.1002/hed.20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leon X, Quer M, Orus CL, et al. Results of salvage surgery for local or regional recurrence after larynx preservation with induction chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2001;23:733–748. doi: 10.1002/hed.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Putten L, Bree R, Kuik DJ, et al. Salvage laryngectomy: oncological and functional outcome. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan HK, Giger R, Auperin A, et al. Salvage surgery after concomitant chemoradiation in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas - stratification for postsalvage survival. Head Neck. 2010;32:139–147. doi: 10.1002/hed.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bree R, Rinaldo A, Genden EM, et al. Modern reconstruction techniques for oral and pharyngeal defects after tumor resection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0413-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esteller E, Vega MC, Lopez M, et al. Salvage surgery after locoregional failure in head and neck carcinoma patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:295–301. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Righini C, Lequeux T, Cuisnier O, et al. The pectoralis myofascial flap in pharyngolaryngeal surgery after radiotherapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:357–361. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fung K, Teknos TN, Vandenberg CD, et al. Prevention of wound complications following salvage laryngectomy using free vascularized tissue. Head Neck. 2007;29:425–430. doi: 10.1002/hed.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith TJ, Burrage KJ, Ganguly P, et al. Prevention of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula: the Memorial University experience. J Otolaryngol. 2003;32:222–225. doi: 10.2310/7070.2003.41697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paleri V, Drinnan M, Brekel MW, et al. Vascularized tissue to reduce fistula following salvage total laryngectomy: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1848–1853. doi: 10.1002/lary.24619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Withrow KP, Rosenthal EL, Gourin CG, et al. Free tissue transfer to manage salvage laryngectomy defects after organ preservation failure. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:781–784. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180332e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shemen LJ, Spiro RH. Complications following laryngectomy. Head Neck Surg. 1986;8:185–191. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herranz J, Sarandeses A, Fernandez MF, et al. Complications after total laryngectomy in nonradiated laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:892–898. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980070020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganly I, Patel S, Matsuo J, et al. Postoperative complications of salvage total laryngectomy. Cancer. 2005;103:2073–2081. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson BJ, Newkirk KA, Harter KW, et al. Complications from planned, posttreatment neck dissections. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:401–405. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goguen LA, Chapuy CI, Li Y, et al. Neck dissection after chemoradiotherapy: timing and complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:1071–1077. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paydarfar JA, Birkmeyer NJ. Complications in head and neck surgery: a meta-analysis of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:67–72. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sassler AM, Esclamado RM, Wolf GT. Surgery after organ preservation therapy. Analysis of wound complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:162–165. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890020024006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timmermans AJ, Lansaat L, Theunissen EA, et al. Predictive factors for pharyngocutaneous fistulization after total laryngectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014;123:153–161. doi: 10.1177/0003489414522972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seitz HK, Stickel F. Molecular mechanism of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrc2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanasono MM, Lin D, Wax MK, et al. Closure of laryngectomy defects in the age of chemoradiation therapy. Head Neck. 2012;34:580–588. doi: 10.1002/hed.21712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavertu P, Bonafede JP, Adelstein DJ, et al. Comparison of surgical complications after organ-preservation therapy in patients with stage III or IV squamous cell head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:401–406. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber RS, Berkey BA, Forastiere A, et al. Outcome of salvage total laryngectomy following organ preservation therapy: the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial 91-11. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:44–49. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inohara H, Tomiyama Y, Yoshii T, et al. [[Complications and clinical outcome of salvage surgery after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma]]. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 2010;113:889–897. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.113.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodwin WJ., Jr Salvage surgery for patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: when do the ends justify the means? Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1–18. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200003001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zafereo ME, Hanasono MM, Rosenthal DI, et al. The role of salvage surgery in patients with recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Cancer. 2009;115:5723–5733. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richey LM, Shores CG, George J, et al. The effectiveness of salvage surgery after the failure of primary concomitant chemoradiation in head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.06.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters TT, Langendijk JA, Plaat BE, et al. Co-morbidity and treatment outcomes of elderly pharyngeal cancer patients: a matched control study. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borggreven PA, Kuik DJ, Langendijk JA, et al. Severe comorbidity negatively influences prognosis in patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer after surgical treatment with microvascular reconstruction. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oskam IM, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Aaronson NK, et al. Quality of life as predictor of survival: a prospective study on patients treated with combined surgery and radiotherapy for advanced oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2010;97:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gourin CG, Starmer HM, Herbert RJ, et al. Short- and longterm outcomes of laryngeal cancer care in the elderly. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:924–933. doi: 10.1002/lary.25012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furuta Y, Homma A, Oridate N, et al. Surgical complications of salvage total laryngectomy following concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:521–527. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Relic A, Scheich M, Stapf J, et al. Salvage surgery after induction chemotherapy with paclitaxel/cisplatin and primary radiotherapy for advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:1799–1805. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-0946-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paleri V, Thomas L, Basavaiah N, et al. Oncologic outcomes of open conservation laryngectomy for radiorecurrent laryngeal carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of English-language literature. Cancer. 2011;117:2668–2676. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klozar J, Cada Z, Koslabova E. Complications of total laryngectomy in the era of chemoradiation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1598-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sewnaik A, Keereweer S, Al-Mamgani A, et al. High complication risk of salvage surgery after chemoradiation failures. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132:96–100. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.617779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Basheeth N, O'Leary G, Sheahan P. Elective neck dissection for no neck during salvage total laryngectomy: findings, complications, and oncological outcome. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:790–796. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki K, Hayashi R, Ebihara M, et al. The effectiveness of chemoradiation therapy and salvage surgery for hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:1210–1217. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyt136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Omura G, Saito Y, Ando M, et al. Salvage surgery for local residual or recurrent pharyngeal cancer after radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2075–2080. doi: 10.1002/lary.24695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powell J, Ullal UR, Ahmed O, et al. Tissue transfer to postchemoradiation salvage laryngectomy defects to prevent pharyngocutaneous fistula: single-centre experience. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;1:1–3. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114000504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newman JP, Terris DJ, Pinto HA, et al. Surgical morbidity of neck dissection after chemoradiotherapy in advanced head and neck cancer. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:117–122. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agra IM, Carvalho AL, Pontes E, et al. Postoperative complications after en bloc salvage surgery for head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1317–1321. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.12.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gleich LL, Ryzenman J, Gluckman JL, et al. Recurrent advanced (T3 or T4) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: is salvage possible? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:35–38. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taussky D, Dulguerov P, Allal AS. Salvage surgery after radical accelerated radiotherapy with concomitant boost technique for head and neck carcinomas. Head Neck. 2005;27:182–186. doi: 10.1002/hed.20139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgan JE, Breau RL, Suen JY, et al. Surgical wound complications after intensive chemoradiotherapy for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:10–14. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Encinas VA, Souviron ER, Rodriguez PA, et al. [Surgical complications in salvage surgery of patients with head and neck carcinomas treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy (CCR)]. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2007;58:454–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simon C, Bulut C, Federspil PA, et al. Assessment of periand postoperative complications and Karnofsky-performance status in head and neck cancer patients after radiation or chemoradiation that underwent surgery with regional or free-flap reconstruction for salvage, palliation, or to improve function. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:109–109. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.León X, Agüero A, López M, et al. Salvage surgery after local recurrence in patients with head and neck carcinoma treated with chemoradiotherapy or bioradiotherapy. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2015;42:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stenson KM, Haraf DJ, Pelzer H, et al. The role of cervical lymphadenectomy after aggressive concomitant chemoradiotherapy: the feasibility of selective neck dissection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:950–956. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.8.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Newkirk KA, Cullen KJ, Harter KW, et al. Planned neck dissection for advanced primary head and neck malignancy treated with organ preservation therapy: disease control and survival outcomes. Head Neck. 2001;23:73–79. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200102)23:2<73::aid-hed1001>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grabenbauer GG, Rodel C, Ernst-Stecken A, et al. Neck dissection following radiochemotherapy of advanced head and neck cancer - for selected cases only? Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kutler DI, Patel SG, Shah JP. The role of neck dissection following definitive chemoradiation. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004;18:993–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brizel DM, Prosnitz RG, Hunter S, et al. Necessity for adjuvant neck dissection in setting of concurrent chemoradiation for advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1418–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frank DK, Hu KS, Culliney BE, et al. Planned neck dissection after concomitant radiochemotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1015–1020. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000162648.37638.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Putten L, Broek GB, Bree R, et al. Effectiveness of salvage selective and modified radical neck dissection for regional pathologic lymphadenopathy after chemoradiation. Head Neck. 2009;31:593–603. doi: 10.1002/hed.20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nouraei SA, Upile T, Al-Yaghchi C, et al. Role of planned postchemoradiotherapy selective neck dissection in the multimodality management of head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:797–803. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318165e33e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vedrine PO, Thariat J, Hitier M, et al. Need for neck dissection after radiochemotherapy? A study of the French GETTEC Group. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1775–1780. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817f192a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Christopoulos A, Nguyen-Tan PF, Tabet JC, et al. Neck dissection following concurrent chemoradiation for advanced head and neck carcinoma: pathologic findings and complications. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:452–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lango MN, Andrews GA, Ahmad S, et al. Postradiotherapy neck dissection for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: pattern of pathologic residual carcinoma and prognosis. Head Neck. 2009;31:328–337. doi: 10.1002/hed.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hillel AT, Fakhry C, Pai SI, et al. Selective versus comprehensive neck dissection after chemoradiation for advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:737–742. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bremke M, Barth PJ, Sesterhenn AM, et al. Prospective study on neck dissection after primary chemoradiation therapy in stage IV pharyngeal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2645–2653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robbins KT, Dhiwakar M, Vieira F, et al. Efficacy of superselective neck dissection following chemoradiation for advanced head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:1185–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yirmibesoglu E, Fried D, Shores C, et al. Incidence of subclinical nodal disease at the time of salvage surgery for locally recurrent head and neck cancer initially treated with definitive radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36:475–480. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182568f9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]