Abstract

Corynebacterium callunae DSM 20147T is a member of the genus Corynebacterium which contains Gram-positive and non-spore forming bacteria with a high G + C content. C. callunae was isolated during a screening for l-glutamic acid producing bacteria and belongs to the aerobic and non-haemolytic corynebacteria. As this is a type strain in a subgroup of industrial relevant bacteria for many of which there are also complete genome sequence available, knowledge of the complete genome sequence might enable genome comparisons to identify production relevant genetic loci. This project, describing the 2.84 Mbp long chromosome and the two plasmids, pCC1 (4.11 kbp) and pCC2 (85.02 kbp), with their 2,647 protein-coding and 82 RNA genes, will aid the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: Aerobic, Non-motile, Gram-positive, Non-spore forming, Glutamic acid producing

Introduction

Strain DSM 20147T is the type strain in a subgroup of industrial relevant bacteria originally isolated during a screening for l-glutamic acid producing microorganisms and was classified to belong to the genus Corynebacterium[1]. This genus is comprised of Gram-positive bacteria with a high G + C content. It currently contains 126 validly published members (species and subspecies), 4 of which are synonyms of other species within the genus, 27 that were later reclassified as members of 7 other genera, and 1 member abolished in erratum [2-11]. The remaining 93 were isolated from diverse backgrounds like soil, sea, or ripening cheese, but also from human clinical samples and animals.

Within this diverse genus, C. callunae has been found to be a producer of l-glutamic acid, like one of the most prominent representatives of the corynebacteria, C. glutamicum[1]. The biological context of this species is, unfortunately, basically unknown as it was first described in a patent application [1] that does neither mention the geographic location nor the exact habitat of the strain. Based on the name and the habitats of its close relatives C. glutamicum, C. deserti, and C. efficiens, the most likely habitat of C. callunae is soil around heather plants. But while the biotechnological uses and capabilities of this subgroup within the genus Corynebacterium has been studied in detail, especially for C. glutamicum, the ability of all these strains to secrete considerable amounts of l-glutamic acid is still not well understood in the context of the environment.

C. callunae DSM 20147T harbors two cryptic plasmids: pCC1 (4,109 bp) which encodes a Rep protein that shows similarity to the corynebacterial plasmid pAG3 and pBL1, and pCC2 (85,023 bp) the Rep protein of which has possible orthologs in many other corynebacteria. Aside from this, DSM 20147T is an alkaline-tolerant bacterium, which grows well at pH 5.0 - 9.0 (optimum pH 6–8) [1]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for C. callunae DSM 20147T, together with the description of the genomic sequencing and annotation.

Organism information

Classification and features

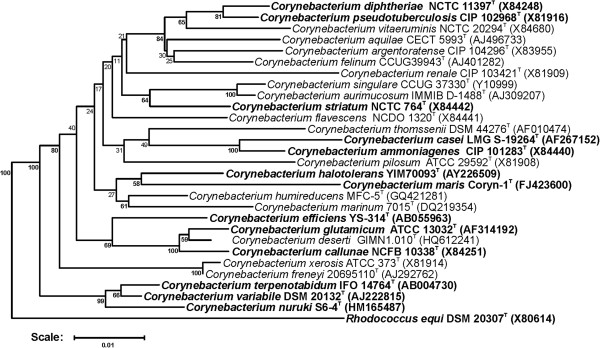

A representative genomic 16S rRNA sequence of C. callunae DSM 20147T was compared to the Ribosomal Database Project database [12] confirming the initial taxonomic classification. C. callunae shows highest similarity to C. glutamicum and C. deserti (97%, respectively).

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of C. callunae in a 16S rRNA based tree. C. callunae forms a subgroup containing furthermore the species C. glutamicum ATCC 13032T, C. deserti GIMN1.010T, and C. efficiens YS-314T.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of C. callunae relative to type strains of other species within the genus Corynebacterium. Species with at least one publicly available genome sequence (not necessarily the type strain) are highlighted in bold face. The tree is based on sequences aligned by the RDP aligner and utilizes the Jukes-Cantor corrected distance model to construct a distance matrix based on alignment model positions without alignment inserts, using a minimum comparable position of 200. The tree is built with RDP Tree Builder, which utilizes Weighbor [13] with an alphabet size of 4 and length size of 1000. The building of the tree also involves a bootstrapping process repeated 100 times to generate a majority consensus tree [14]Rhodococcus equi (X80614) was used as an outgroup.

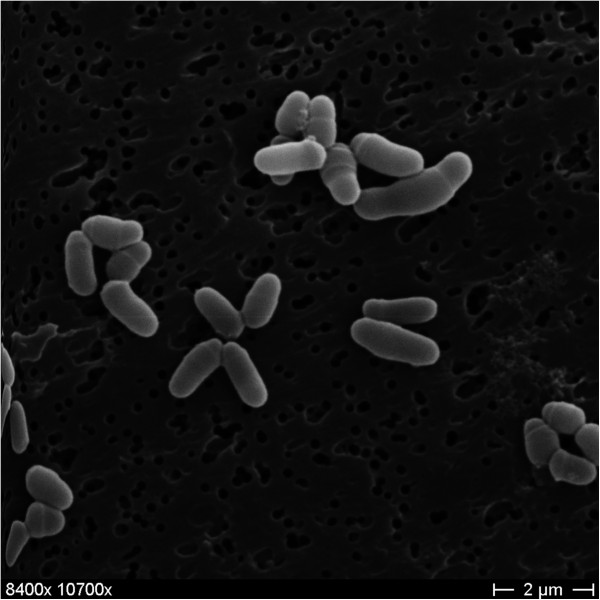

C. callunae DSM 20147T is a Gram-positive rod shaped bacterium, which is 1–2 μm long and 0.4-0.6 μm wide (Figure 2). It is described to be non-motile [1], which coincides with a complete lack of genes associated with ‘cell motility’ (functional category N in COGs table). Growth of DSM 20147T was shown at temperatures between 25–37°C with optimal l-glutamic acid production between 25–35°C [1]. Carbon sources utilized by strain DSM 20147T include dextrose, fructose, galactose, inulin, inositol, maltose, mannitol, mannose, raffinose, salicin, sucrose and trehalose [1]. DSM 20147T tested positive for citrate, catalase and urease, but shows no nitrate reduction activity [1]. Details on the chemotaxonomy are largely missing, but can be inferred from the close relatives C. glutamicum, C. efficiens, and C. deserti[3]. Based on these relatives, meso-diaminopimelic acid is expected to be the major diamino acid of the cell wall, with arabinose and galactose as the main sugars (chemotype IV). Short-chain mycolic acids (32 ± 36 carbon atoms) are also certain to be present, as all necessary genes were found to be present. The major cellular fatty acids are expected to be hexadecanoic acid (C16:0, 40-50%) and octadecenoic acid (C18:1ω9c, 40-50%) with small amounts of octadecanoic acid (C18:0, ~1%) and possible others. MK-9(H2) is thought to be the major menaquinone, although MK-8(H2) might also be present in significant amounts. Phosphatidylinositol, diphosphatidylglycerol, and phosphatidylglycerol as well as their glycosides are expected to be the main components of the polar lipids (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of C. callunae DSM 20147 T .

Table 1.

Classification and general features of C. callunae DSM 20147 T according to the MIGS recommendations[15]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [16] | |

| Phylum ‘Actinobacteria’ | TAS [17] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [18,19] | ||

| Order Actinomycetales | TAS [18,20-22] | ||

| Family Corynebacteriaceae | TAS [18,20,22,23] | ||

| Genus Corynebacterium | TAS [24,25] | ||

| Species Corynebacterium callunae | TAS [1,22,26] | ||

| Type-strain DSM 20147 | TAS [1,22,26] | ||

| Gram stain | Positive | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | Rod-shaped | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | Non-motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | TAS [1] | |

| pH range | 5 - 9; optimum 6 - 8 | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | Not reported | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobe | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | Dextrose, fructose, galactose, inulin, inositol, maltose, mannitol, mannose, raffinose, salicin, sucrose and trehalose | TAS [1] | |

| Energy metabolism | Chemoorganoheterotrophic | NAS | |

| Terminal electron acceptor | Oxygen | NAS | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Not reported | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogenic | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | NAS | |

| MIGS-23.1 | Isolation | Not reported | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Not reported | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | Not reported | TAS [1] |

a)Evidence codes - TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [27].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

Due to its phylogenetic position in the near neighborhood of industrial relevant species of the genus Corynebacterium, C. callunae was selected for sequencing as part of a project to define production relevant loci in corynebacteria. While not being part of the GEBA project, sequencing of the type strain will nonetheless aid the GEBA effort. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database [28] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed at the CeBiTec. A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genome sequencing project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Nextera DNA Sample Prep Kit, Nextera Mate Pair Sample Prep Kit |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina MiSeq |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 99.51× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.8 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | GeneMark, Glimmer |

| Locus Tag | H924 | |

| Genbank ID | CP004354, CP004355, CP004356 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | March 6, 2013 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc0042965 | |

| BIOPROJECT ID | 190670 | |

| Project relevance | Industrial, GEBA | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 20147 |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

C. callunae DSM 20147T was grown aerobically in CASO bouillon (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) at 30°C. DNA was isolated from ~ 108 cells using the protocol described by Tauch et al. [29].

Genome sequencing and assembly

Two libraries were prepared: a WGS library using the Illumina-Compatible Nextera DNA Sample Prep Kit (Epicentre, WI, U.S.A) and a 6 k MatePair library using the Nextera Mate Pair Sample Preparation Kit, both according to the manufacturer's protocol. Both libraries were sequenced in a 2× 250 bp paired read run on the MiSeq platform, yielding 1,747,266 total reads, providing 99.51× coverage of the genome. Reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler v2.8 (Roche). The initial Newbler assembly consisted of 29 contigs in four scaffolds. Analysis of the four scaffolds revealed two to be an extrachromosomal element (plasmid pCC1 and pCC2), one to make up the chromosome and the remaining one containing the seven copies of the RRN operon.

The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package [30-33] was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment in the subsequent finishing process, gaps between contigs were closed by manual editing in Consed (for repetitive elements).

Genome annotation

Gene prediction and annotation were done using the PGAP pipeline [34]. Genes were identified using GeneMark [35], GLIMMER [36], and Prodigal [37]. For annotation, BLAST searches against the NCBI Protein Clusters Database [38] are performed and the annotation is enriched by searches against the Conserved Domain Database [39] and subsequent assignment of coding sequences to COGs. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [40], Infernal [41], RNAMMer [42], Rfam [43], TMHMM [44], and SignalP [45].

Genome properties

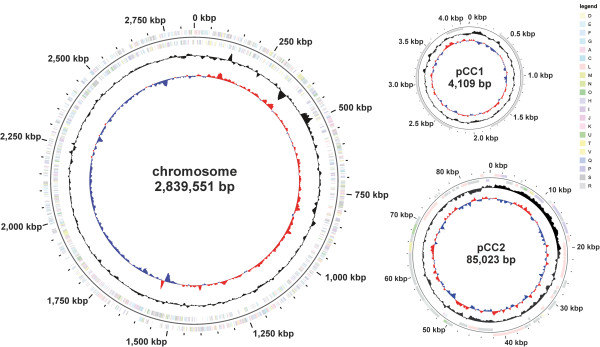

The genome (on the scale of 2,928,683 bp) includes one circular chromosome of 2,839,5514 bp (52.39% G + C content) and two plasmids of 4,109 bp (54.42% G + C content) and 85,023 bp (54.38% G + C content, [Figure 3]). For chromosome and plasmids, a total of 2,729 genes were predicted, 2,647 of which are protein coding genes. 2,085 (76.40%) of the protein coding genes were assigned to a putative function, the remaining were annotated as hypothetical proteins. 1,937 protein coding genes belong to 314 paralogous families in this genome corresponding to a gene content redundancy of 41.52%. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in [Tables 3, 4 and 5].

Figure 3.

Graphical map of the chromosome and the two plasmids pCC1 and pCC2 (not drawn to scale). From the outside in: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), GC content, GC skew.

Table 3.

Summary of genome: one chromosome and two plasmids

Table 4.

Genome statistics

| Attribute | Value | % of total a |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,928,683 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 2,678,511 | 91.46 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 1,536,292 | 52.46 |

| DNA scaffolds | 3 | |

| Total genes | 2,729 | 100.00 |

| Protein coding genes | 2,647 | 97.00 |

| RNA genes | 82 | 3.00 |

| Pseudo genes | 61 | 2.24 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 1,937 | 64.05 |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,085 | 76.40 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,748 | 41.52 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 2,125 | 5.06 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 158 | 5.79 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 673 | 24.66 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 |

a)The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of total genes in the annotated genome.

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 148 | 5.59 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.04 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 174 | 6.57 | Transcription |

| L | 192 | 7.25 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.00 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 20 | 0.76 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 41 | 1.55 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 66 | 2.49 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 116 | 4.38 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 1 | 0.04 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.00 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 1 | 0.04 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 28 | 1.06 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 76 | 2.87 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 115 | 4.34 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 173 | 6.54 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 244 | 9.22 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 74 | 2.80 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 107 | 4.04 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 57 | 2.23 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 182 | 6.88 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 53 | 2.00 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 315 | 11.90 | General function prediction only |

| S | 170 | 6.42 | Function unknown |

| - | 629 | 23.76 | Not in COGs |

Insights from the genome sequence

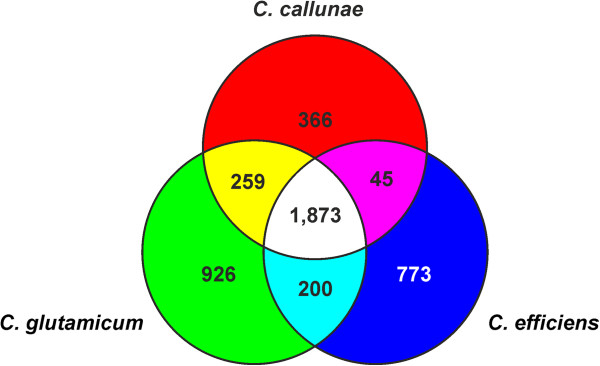

The complete genome sequence of C. callunae was already mined for biotechnological purposes to define the core genome of the C. glutamicum - C. efficiens - C. callunae subgroup to define the chassis genome for C. glutamicum[46]. Comparison of the three genomes using EDGAR [47] reveals that the core genome of this group comprises just 1,873 genes and the number of genes that are found only in C. callunae is also relatively small (366), especially when compared to number of singletons found in the other two (926 and 773 in C. glutamicum and C. efficiens, respectively; Figure 4). As C. callunae was shown to produce l-glutamate in an amount comparable to C. glutamicum, C. callunae might be considered as a potential candidate for future genome reduction efforts since the chromosome is already considerably smaller than that of C. glutamicum and C. efficiens (2.84 Mbp versus 3.21 Mbp and 3.15 Mbp, respectively). This future approach is aided by the observation that many of the singletons are clustered in just three regions (I: H924_2045-H924_02230, 37 genes, 25.2 kbp; II: H924_03630-H924_03880, 50 genes 52.5 kbp; III: H924_07070-H924_07380, 61 genes, 48.2 kbp) which constitutes ~ 4.4% of the genome size. As at least region II and region III are likely prophages, loss of these regions should be neutral or even beneficial, as demonstrated for C. glutamicum[48].

Figure 4.

Venn diagram depicting the number of genes shared between C. callunae, C. glutamicum, and C. efficiens. EDGAR [47] was used to determine the core genomes shared between respectively singletons unique to the three species.

One central prerequisite for future rational strain development is the genetic accessibility of the prospective strain. Knowledge of the complete genome sequence of C. callunae helps to overcome at least two of the main obstacles: the construction of plasmids usable as vectors and removal of elements that hinder DNA transfer. For the former, the knowledge of the sequences of the two plasmids pCC1 and pCC2 allows use of plasmid-tagging approaches via a counter-selectable marker [49] to cure them, should conventional approaches like heat-shock curing fail. Once cured, the sequence of the plasmids help to identify the minimal gene set necessary for replication to build shuttle vectors, as demonstrated for pCC1 [50]. For the latter, the genome sequence helps to identify restriction-modification systems. A preliminary analysis revealed the presence of at least 4 such systems, one of which is located in the potential prophage region II. Removal of such systems has been shown to significantly enhance the stability of foreign DNA introduced and thus facilitating genetic engineering approaches [48].

Conclusion

The complete genome sequence of C. callunae is the third genome sequence of the C. glutamicum - C. deserti - C. efficiens - C. callunae subgroup of L-glutamic acid producing corynebacteria within the genus Corynebacterium. Knowledge of the complete genome sequence has already contributed to identify the core genome of this group. With a size of 2.84 Mbp and an a total of 2,647 protein coding genes, the genome of C. callunae is by far the smallest within this group. Therefore, this bacterium might be an ideal choice for future development of a platform strain as the otherwise high degree of similarity of its genome content to the well studied C. glutamicum would allow an easy transfer of knowledge to the new host. Furthermore, knowledge of the complete genome sequence also facilitates the identification of possible targets to improve the accessibility to genetic engineering (like restriction-modification systems) and to enhance genome stability (like phages and transposases).

Abbreviations

CeBiTec: Center for Biotechnology; GEBA: Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors contributions

MP prepared and wrote the manuscript, AA performed library preparation and sequencing, HB and KN performed electron microscopy, JK coordinated the study, and CR assembled and analyzed the genome sequence.

Contributor Information

Marcus Persicke, Email: marcusp@cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de.

Andreas Albersmeier, Email: aalbersm@cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de.

Hanna Bednarz, Email: hanna@cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de.

Karsten Niehaus, Email: kniehaus@cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de.

Jörn Kalinowski, Email: joern@cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de.

Christian Rückert, Email: Christian.Rueckert@CeBiTec.Uni-Bielefeld.DE.

Acknowledgements

Christian Rückert acknowledges funding through a grant by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (0316017A) within the BioIndustry2021 initiative. We acknowledge support for the Article Processing Charge by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Open Access Publication Funds of Bielefeld University Library.

References

- Lee WH, Good RC. Book Amino Acid Synthesis (Editor ed.^eds.) City: International Minerals & Chemical Corporation; 1963. Amino Acid Synthesis; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-Y, Zhuang L, Zhou S-G, Li F-B, He J. Corynebacterium humireducens sp. nov., an alkaliphilic, humic acid-reducing bacterium isolated from a microbial fuel cell. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;61:882–887. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.020909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akasaka H, Akimov VN, Anderson RC, Ariskina EV, Austin B, Behrendt U, Benno Y, Benson DR, Bernard KA, Berry AM, Biavati B, Buczolits S, Busse H-J, Butler WR, Carro L, Cavaletti L, Chen W-F, Collins MD, Costa MSd, Cui X-L, Denner EBM, Dewhirst FE, Donadio S, Dorofeeva LV, Euzéby JP, Evtushenko LI, Fernández-Garayzábal JF, Franco C, Funke G, Garrity GM. The Actinobacteria. 2. New York: Springer Verlag; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aravena-Román M, Spröer C, Siering C, Inglis T, Schumann P, Yassin AF. Corynebacterium aquatimens sp. nov., a lipophilic Corynebacterium isolated from blood cultures of a patient with bacteremia. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2012;35:380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Validation List No. 148. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:2549–2554. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Yuan M, Tang R, Chen M, Lin M, Zhang W. Corynebacterium deserti sp. nov., isolated from desert sand. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:791–794. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.030429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischmann A, Knoll A, Hilbert F, Zasada AA, Kämpfer P, Busse H-J. Corynebacterium epidermidicanis sp. nov., isolated from skin of a dog. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:2194–2200. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.036061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiertz R, Schulz SC, Müller U, Kämpfer P, Lipski A. Corynebacterium frankenforstense sp. nov. and Corynebacterium lactis sp. nov., isolated from raw cow milk. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:4495–4501. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.050757-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin N-R, Jung M-J, Kim M-S, Roh SW, Nam Y-D, Bae J-W. Corynebacterium nuruki sp. nov., isolated from an alcohol fermentation starter. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;61:2430–2434. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.027763-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyles L, Ortman K, Cardew S, Foster G, Rogerson F, Falsen E. Corynebacterium uterequi sp. nov., a non-lipophilic bacterium isolated from urogenital samples from horses. Vet Microbiol. 2013;165:469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren A, Garrity GM. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:3931–3934. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, Fish J, Chai B, Farris RJ, Kulam-Syed-Mohideen AS, McGarrell DM, Marsh T, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM. The ribosomal database project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno WJ, Socci ND, Halpern AL. Weighted neighbor joining: a likelihood-based approach to distance-based phylogeny reconstruction. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:189–197. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JR, Chai B, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam-Syed-Mohideen AS, McGarrell DM, Bandela AM, Cardenas E, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM. The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): introducing myRDP space and quality controlled public data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D169–D172. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, Ashburner M, Axelrod N, Baldauf S, Ballard S, Boore J, Cochrane G, Cole J, Dawyndt P, De Vos P, DePamphilis C, Edwards R, Faruque N, Feldman R, Gilbert J, Gilna P, Glockner FO, Goldstein P, Guralnick R, Haft D, Hancock D. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity GM, Holt JG. In: Bergey´s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. 2. Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW, editor. Vol. 1. New York: Springer; 2001. The Road Map to the Manual; pp. 119–169. [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a New hierarchic classification system, actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:479–491. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Euzéby JP, Tindall BJ. Nomenclatural type of orders: corrections necessary according to Rules 15 and 21a of the Bacteriological Code (1990 Revision), and designation of appropriate nomenclatural types of classes and subclasses. Request for an opinion. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:725–727. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-2-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:589–608. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of the bacteria: II. The primary subdivisions of the schizomycetes. J Bacteriol. 1917;2:155–164. doi: 10.1128/jb.2.2.155-164.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann KB, Neumann RO. Lehmann's Medizin, Handatlanten. X Atlas und Grundriss der Bakteriologie und Lehrbuch der speziellen bakteriologischen Diagnostik. 4. München: J.F. Lehmann; 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard KA, Wiebe D, Burdz T, Reimer A, Ng B, Singh C, Schindle S, Pacheco AL. Assignment of Brevibacterium stationis (ZoBell and Upham 1944) Breed 1953 to the genus Corynebacterium, as Corynebacterium stationis comb. nov., and emended description of the genus Corynebacterium to include isolates that can alkalinize citrate. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:874–879. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.012641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann KB, Neumann RO. Atlas und Grundriss der Bakteriologie und Lehrbuch der speziellen bakteriologischen Diagnostik. München: J.F. Lehmanns Verlag; 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Komagata K. Taxonomic studies on coryneform bacteria. V. Classification of coryneform bacteria. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1972;18:417–431. doi: 10.2323/jgam.18.417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;38:D346–D354. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauch A, Kassing F, Kalinowski J, Pühler A. The erythromycin resistance gene of the Corynebacterium xerosis R-plasmid pTP10 also carrying chloramphenicol, kanamycin, and tetracycline resistances is capable of transposition in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Plasmid. 1995;33:168–179. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D. Viewing and editing assembled sequences using Consed. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 2003;11(2):1–43. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1102s02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 1998;8:195–202. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokaryotic Genomes Automatic Annotation Pipeline (PGAAP) [ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174280/]

- Borodovsky M, Mills R, Besemer J, Lomsadze A. Prokaryotic gene prediction using GeneMark and GeneMark.hmm. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 2003;4(5):1–16. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0405s01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher AL, Harmon D, Kasif S, White O, Salzberg SL. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4636–4641. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.23.4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimke W, Agarwala R, Badretdin A, Chetvernin S, Ciufo S, Fedorov B, Kiryutin B, O'Neill K, Resch W, Resenchuk S, Schafer S, Tolstoy I, Tatusova T. The national center for biotechnology Information's protein clusters database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D216–D223. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Tasneem A, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zhang N, Bryant SH. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D205–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy SR. A memory-efficient dynamic programming algorithm for optimal alignment of a sequence to an RNA secondary structure. BMC Bioinform. 2002;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR, Bateman A. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D121–D124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unthan S, Baumgart M, Radek A, Herbst M, Siebert D, Brühl N, Bartsch A, Bott M, Wiechert W, Marin K, Hans S, Kramer R, Seibold G, Frunzke J, Kalinowski J, Rückert C, Wendisch VF, Noack S. Chassis organism from Corynebacterium glutamicum - a top-down approach to identify and delete irrelevant gene clusters. Biotechnol J. in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/biot.201400041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blom J, Albaum SP, Doppmeier D, Puhler A, Vorholter FJ, Zakrzewski M, Goesmann A. EDGAR: a software framework for the comparative analysis of prokaryotic genomes. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-154. Chapter 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgart M, Unthan S, Rückert C, Sivalingam J, Grünberger A, Kalinowski J, Bott M, Noack S, Frunzke J. Construction of a prophage-free variant of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 - a platform strain for basic research and industrial biotechnology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:6006–6015. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01634-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger W, Schäfer A, Pühler A, Labes G, Wohlleben W. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis sacB gene leads to sucrose sensitivity in the gram-positive bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum but not in Streptomyces lividans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5462–5465. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5462-5465.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkova-Canova T, Pátek M, Nešvera J. Characterization of the cryptic plasmid pCC1 from Corynebacterium callunae and its use for vector construction. Plasmid. 2004;51:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]