Abstract

During spermatogenesis, developing spermatids and preleptotene spermatocytes are transported across the adluminal compartment and the blood-testis barrier (BTB), respectively, so that spermatids line up near the luminal edge to prepare for spermiation, whereas preleptotene spermatocytes enter the adluminal compartment to differentiate into late spermatocytes to prepare for meiosis I/II. These cellular events involve actin microfilament reorganization at the testis-specific, actin-rich Sertoli-spermatid and Sertoli-Sertoli cell junction called apical and basal ectoplasmic specialization (ES). Formin 1, an actin nucleation protein known to promote actin microfilament elongation and bundling, was expressed at the apical ES but limited to stage VII of the epithelial cycle, whereas its expression at the basal ES/BTB stretched from stage III to stage VI, diminished in stage VII, and was undetectable in stage VIII tubules. Using an in vitro model of studying Sertoli cell BTB function by RNA interference and biochemical assays to monitor actin bundling and polymerization activity, a knockdown of formin 1 in Sertoli cells by approximately 70% impeded the tight junction-permeability function. This disruptive effect on the tight junction barrier was mediated by a loss of actin microfilament bundling and actin polymerization capability mediated by changes in the localization of branched actin-inducing protein Arp3 (actin-related protein 3), and actin bundling proteins Eps8 (epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8) and palladin, thereby disrupting cell adhesion. Formin 1 knockdown in vivo was found to impede spermatid adhesion, transport, and polarity, causing defects in spermiation in which elongated spermatids remained embedded into the epithelium in stage IX tubules, mediated by changes in the spatiotemporal expression of Arp3, Eps8, and palladin. In summary, formin 1 is a regulator of ES dynamics.

The seminiferous epithelium in the mammalian testis is divided into the basal and the adluminal compartment by the blood-testis barrier (BTB) (1–3). Preleptotene spermatocytes transformed from type B spermatogonia residing in the basal compartment are transported across the BTB, which are further developed into pachytene spermatocytes in the adluminal compartment, undergoing meiosis I/II (4, 5) at stage XIV of the epithelial cycle in the rat testis. Once haploid step 1 spermatids are formed, they are being transported back and forth across the adluminal compartment, while differentiating into step 19 spermatids via spermiogenesis, until elongated spermatids line up near the luminal edge at stage VIII of the cycle (4, 5). Thus, spermatozoa differentiated from step 19 spermatids can be released into the tubule lumen at spermiation at late stage VIII of the cycle (6–8). Germ cell transport across the seminiferous epithelium relies on testis-specific anchoring junction known as ectoplasmic specialization (ES) at the Sertoli cell-cell interface known as the basal ES, which together with the tight junction (TJ) creates the BTB, and at the Sertoli-spermatid interface called apical ES, which are restricted to the basal and the adluminal compartment, respectively (9–13). ES is typified by the presence of bundles of actin microfilaments that lie perpendicular to the Sertoli cell plasma membrane, and these actin filament bundles are sandwiched between the cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum and the apposing Sertoli-Sertoli (basal ES) and Sertoli-spermatid (apical ES) plasma membranes (9, 10, 12, 14). Thus, it is conceivable that these bundles of actin microfilaments at the ES must be rapidly reorganized involving proteins that regulate actin polymerization and depolymerization as well as microfilament bundling and unbundling (3, 15).

The actin-related protein 2/3 (Arp2/3) complex is known to induce branched actin nucleation of an existing actin microfilament by effectively converting bundled actin microfilaments to a branched/unbundled network in the testis (16). The Arp2/3 complex is working in concert with the actin barbed end capping/bundling protein, epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8) (17), and also actin cross-linking/bundling protein palladin (18) to provide an efficient mechanism to reorganize actin microfilament bundles at the ES. Their differential actions rapidly convert actin microfilaments from a bundled to an unbundled/branched state and vice versa during the epithelial cycle (15). However, actin nucleation proteins that promote the generation of long stretches of microfilaments, which can be bundled at the ES, are not known.

Formin 1 is an 180-kDa actin nucleation protein known to promote the progressive addition of actin monomers onto the plus end of a growing actin microfilament by nucleating actin molecules from the barbed end, effectively creating a network of actin microfilaments as long as greater than 50 μm (19, 20), such as microfilaments in actin stress fibers for focal adhesion and in filopodium (20, 21). Formin 1 is detected in cells of the kidney, limb, ovary, brain, small intestine, salivary gland, and testis (22, 23). Formin 1 is also a member of a large family of morphoregulatory proteins known as formins, which was initially shown to regulate limb pattern formation, and they are the products of the limb deformity (ld) gene via alternative mRNA splicing in the mouse, and its mutation leads to limb deformation in rodents (23, 24). Furthermore, formins are found in flies, yeasts, and mice and are well conserved across species (20). Subsequent studies have shown that members of the large formin protein family are encoded by at least 15 genes in mammals (20). Formins also contain F-actin bundling domain in addition to their intrinsic actin nucleation activity for the assembly of adherens junctions (20, 22) in epithelia, and they are also involved in cytokines, cell polarity, and cell locomotion along with cell and tissue morphogenesis and tumorigenesis (20, 21, 25, 26). Herein we examined the cellular expression of formin 1 in the testis, including its stage-specific expression/localization, and its functional significance at the basal and apical ES, in particular its role in the organization of actin microfilaments during spermatogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals and antibodies

Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. The use of animals was approved by the Rockefeller University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee with protocol number 12-506. Antibodies obtained commercially are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Primary Sertoli cell cultures

Sertoli cells were isolated from testes of 20-day-old pups and cultured in serum-free F12/DMEM [Ham's F12 nutrient mixture/DMEM) (Sigma-Aldrich; 50%/50% (vol/vol)], supplemented with growth factors and gentamicin at 35°C with 95% air-5% CO2 (vol/vol) in a humidified atmosphere as described (27). Freshly isolated Sertoli cells were plated on Matrigel (BD Biosciences; diluted 1:7 with F12/DMEM medium)-coated coverslips at 0.04–0.08 × 106 cell/cm2, which were then placed in 12-well dishes containing 2-mL F12/DMEM to be used for dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis or at 0.4 × 106 cell/cm2 in six-well dishes containing 5 mL F12/DMEM to be used for lysate preparation and RNA extractions. Thirty-six hours thereafter, cultures were subjected to a hypotonic treatment using 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4) at 22°C for 2.5 minutes (28) to lyse residual germ cells. Sertoli cell cultures were approximately 98% pure, with negligible contamination of Leydig, peritubular myoid, or germ cells using corresponding specific markers examined by immunoblotting or RT-PCR (29). Germ cells were isolated from adult rat testes, cultured in F12/DMEM supplemented with sodium lactate and sodium pyruvate (30) and used for RNA extraction or lysate preparation within 12 hours with a cell viability greater than 95% (31).

Knockdown of Sertoli cell formin 1 in vitro by RNA interference (RNAi)

Sertoli cells were cultured alone for 3 days to allow the establishment of a functional TJ-permeability barrier, containing ultrastructures of TJ, basal ES, gap junction, and desmosome, mimicking the BTB in vivo (32, 33). Thereafter cells were transfected with formin 1-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes vs nontargeting negative control siRNA duplexes at 50 nM by suspending in Opti-MEM (Life Technologies) for 24 hours using RNAiMAX (Life Technologies) as a transfection reagent at 0.3% (vol/vol). In short, Opti-MEM was at 12% (vol/vol) of the total transfection reagent mixture using F12/DMEM as the dilution buffer for all in vitro RNAi experiments. The two siRNA primers that generate the formin 1 siRNA duplex specific for Sprague Dawley rats are shown in Supplemental Table 2. The formin 1-specific siRNA duplex and nontargeting siRNA control duplexes [Stealth RNAi negative control duplexes] were purchased from Invitrogen. After transfection, cells were rinsed twice in F12/DMEM to remove transfection reagents and cultured for an additional 24 hours before cells were terminated for immunofluorescence analysis (IF) or for lysate preparation and RNA extraction. For IF, cells were cotransfected with 1 nM siGLO red transfection indicator (Dharmacon) to track successful transfection.

Assessment of Sertoli cell TJ permeability in vitro

Sertoli cells were plated on Matrigel (1:5 freshly diluted with F12/DMEM)-coated Millicell HA (mixed cellulose esters) cell culture inserts (diameter 12 mm; pore size 0.45 μm, effective surface area ∼0.6 cm2; EMD Millipore) at 1.2 × 106 cell/cm2. Bicameral units were then placed in 24-well dishes. Each insert contained 0.5 mL F12/DMEM in the apical and basal compartments, and the concentration of siRNA duplexes was 100 nM in both compartments. Sertoli cell TJ permeability was quantified daily by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance across the cell epithelium as described (27).

Actin bundling assay

An actin bundling assay was performed as described (34). In brief, F-actin was obtained from G-actin using an actin binding protein biochemical kit (Cytoskeleton; catalog number BK013). These actin microfilaments served as the substrate to assess the ability of Sertoli cell lysates to induce actin microfilament bundling. Cell lysates were obtained from Sertoli cells previously transfected with formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes vs nontargeting negative control duplexes using 100 μL Tris lysis buffer [20 mM Tris, 20 mM NaCl, and 0.5% Triton X-100 (vol/vol) (pH 7.5) at 22°C, freshly supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich) at a 1:100 dilution (vol/vol)], and cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 20 800 × g at 4°C for 1 hour. Ten microliters of cell lysates containing approximately 20–30 μg protein from both groups (clear supernatant from the above step) containing equal amount of protein vs 10 μL Tris lysis buffer (served as a negative control) were then added into 40 μL of freshly prepared F-actin obtained above. This mixture was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature to allow actin bundling, and then centrifuged at 14 000 × g for 5 minutes at 24°C to sediment bundled F-actin in the pellet, whereas unbundled actin microfilaments remained in the supernatant. The whole pellet and an aliquot (5 μL) of supernatant of each sample from both groups vs negative control were analyzed by immunoblotting using a β-actin antibody (Supplemental Table 1). Cell lysate (∼30 μg protein) from each sample was also analyzed by immunoblotting to monitor the efficiency of formin 1 knockdown and served as a protein loading control.

Actin polymerization assay

Effects of formin 1 knockdown vs control on actin polymerization were assessed by comparing the initial rate of fluorescence increase that occurred when pyrene-conjugated G-actin was polymerized using actin polymerization biochemical kits from Cytoskeleton (35, 36). In brief, lyophilized pyrene-conjugated G-actin was reconstituted to 20 mg/mL with ice cool sterile water and then diluted to 0.4 mg/mL with general actin buffer and placed on ice for 1 hour to depolymerize actin oligomers, and the pyrene-conjugated G-actin was subsequently centrifuged at 14 000 × g at 4°C for 30 minutes before use. Sertoli cell lysates obtained from cultures transfected with formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes vs nontargeting negative control duplexes using Tris lysis buffer as described above for actin bundling assay were used in this actin polymerization assay. Twenty microliters of cell lysates with equal amounts of protein (∼40–60 μg) were added to the final reaction mix containing 200 μL of diluted pyrene-conjugated G-actin and 20 μL of 10× actin polymerization buffer. The kinetics of fluorescence increase were monitored in a Corning 96-well black flat-bottom polystyrene microplate (via top reading) by enhanced fluorescence emission at 395–440 nm using a FilterMax F5 multimode microplate reader and the Multi-Mode Analysis software (Molecular Devices). The reading was taken at room temperature every 20 seconds for 100 cycles with an excitation filter/emission filter at 360 nm/430 nm with an integration time of 25 μsec. The relative initial rate of actin polymerization (0–8 min) assessed by the rate of increase in fluorescence intensity was obtained by linear regression analysis using Microsoft Excel. Each sample was run in duplicate, and this experiment was repeated three times and yielded similar results.

Formin 1 silencing in adult rat testis in vivo

To knock down formin 1 in vivo, rats (∼325–350 g body weight) were transfected with siRNA duplexes via intratesticular injection using a 28-gauge needle as described (37). In brief, on day 0, day 1, and day 2, one testis of the adult rat received nontargeting negative control siRNA duplexes vs the other testis of the same rat that received formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes (n = 6 rats), which was shown to perturb the Sertoli cell TJ barrier in vitro. siRNA duplexes at the desired concentration (100 nM) were suspended in a 200-μL transfection mixture containing 3 μL RNAiMAX reagent and 193 μL Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (Invitrogen). Thus, each testis (∼1.6 g, a volume of ∼1.6 mL) received 200 μL of this transfection mixture. In short, the 28-gauge (13 mm long) needle attached to an insulin syringe was loaded longitudinally from the apical to the basal end of the testis, and as the needle was withdrawn apically, the transfection mixture was gradually and gently released from the syringe so that the entire testis was filled with the 200-μL mixture that spread across the testis, avoiding an acute rise in intratesticular hydrostatic pressure. Rats (n = 6) were euthanized on day 5. Thus, three rat testes were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until used for immunoblotting or RNA extraction or to obtain frozen sections for IF; and the other testes (n = 3) from three rats were fixed in Bouin's fixative to obtain paraffin sections for histological analysis.

Immunoblotting, coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP), and RT-PCR

Lysates obtained from cells and testes were used for immunoblotting by chemiluminescence as described (38). Co-IP was performed using lysates of adult rat testes (∼600 μg protein) and corresponding antibodies (Supplemental Table 1) (35). RNA extraction and PCR using specific primer pairs (Supplemental Table 2) were performed as described (39). PCR products were verified by direct DNA sequencing at Genewiz.

Dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis

Dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis was performed using frozen sections of testes and corresponding primary antibodies (Supplemental Table 1) as described (35, 36). Negative control included the use of normal IgG of the corresponding host animals: mouse, rabbit, or goat (Supplemental Table 1). Cross-sections of testes or cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 555 for red fluorescence; Alexa Fluor 488 for green fluorescence; Invitrogen). For F-actin staining, testis sections or cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich) or with rhodamine-phalloidin (40). Slides were mounted in Prolong Gold Antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; a nuclei stain; Invitrogen). Fluorescence images were acquired using an Olympus BX61 fluorescence microscope with a built-in Olympus DP70 12.5-MPx digital camera and analyzed using the Olympus MicroSuite Five software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solution Corp). Adobe Photoshop in Adobe Creative Suite (version 3.0) was used for image overlay to assess protein colocalization. All sections or cells between treatment and control groups were performed in a single experimental session to avoid interexperimental variations. Data shown were representative micrographs from a single experiment, and each experiment was performed at least three times.

Image analysis

For Sertoli cells after RNAi to silence formin 1, at least 200 cells were randomly selected and examined in experimental vs control groups in three independent experiments. Fluorescence intensity of a target protein in Sertoli cells or in the seminiferous epithelium of testes was quantified using Image J (version 1.45; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). At least 50 randomly selected stage VI-IX tubules from cross-sections of a rat testis were examined with ∼150 VI-IX tubules in three rats. Analysis was focused on these stages due to the stage-specific expression of formin 1 at the apical vs the basal ES. Also, defects in spermiation and spermatid polarity were readily detected in these stages.

General method

Protein estimation was performed using a Bio-Rad Laboratories DC protein assay kit. Cell cytotoxicity was assessed by a sodium 3′-[1-(phenylaminocarbonyl)-3′4-tetrazolium]-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro) benzene sulfonic acid hydrate assay (Roche Diagnostics) as described (33).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the GB-STAT software package (version 7.0; Dynamic Microsystems). Statistical analysis was performed by a two-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett's test. In selected experiments, a Student's t test was used for paired comparisons.

Results

Cellular and stage-specific expression of formin 1 in rat testes

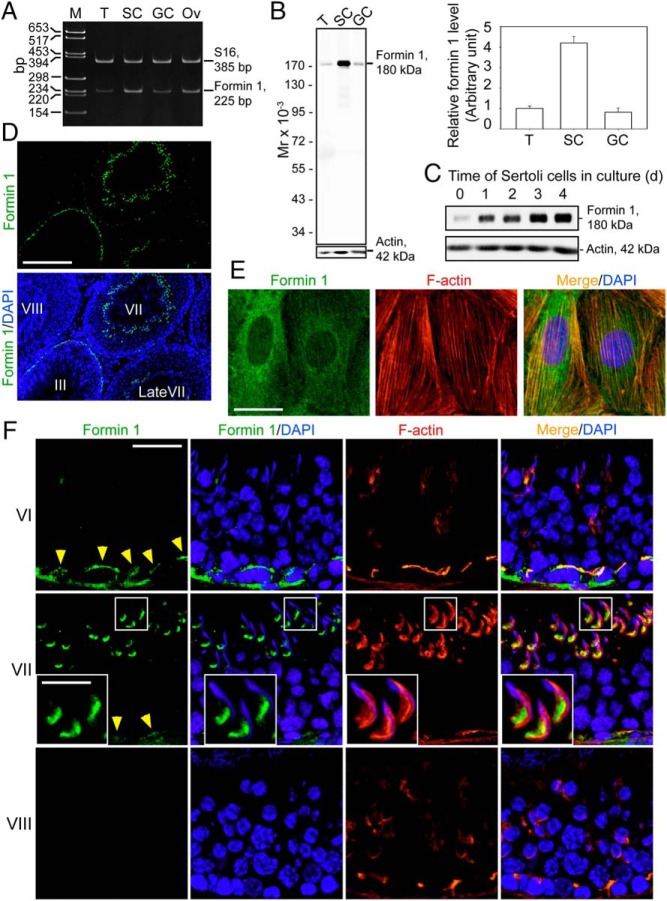

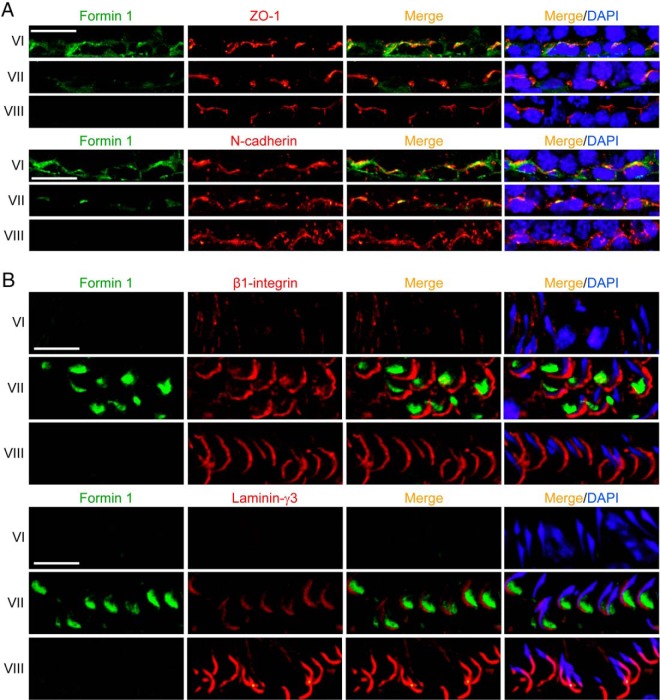

By RT-PCR using a primer pair specific to formin 1 with S16 as the PCR and loading control (Supplemental Table 2), Sertoli cells (SC) and GCs were shown to express formin 1 with the ovary serving as a positive control (Figure 1A). The identity of the PCR product was confirmed by direct nucleotide sequencing and shown to be formin 1. Furthermore, immunoblot analysis confirmed the expression of formin 1 (molecular weight 180 kDa) in the testis, with Sertoli cells being the predominant contributor of formin 1 in the testis (Figure 1B), consistent with findings by RT-PCR (Figure 1B v. 1A). Sertoli cells were also shown to display an up-regulation on the expression of formin 1 during their culture in vitro from day 0 to 4 (Figure 1C). Immunoblot analysis also supported the specificity of the antiformin 1 antibody (Supplemental Table 1). This antiformin 1 antibody was used for IF, which illustrated the stage-specific expression of formin 1 at the apical ES (eg, stage VII tubules but not in stage VIII tubules) and the basal ES (eg, stage VI and VII tubules but not in stage VIII tubules) (Figure 1D). Stages of the epithelial cycle was defined as earlier described (41, 42). Sertoli cells cultured in vitro for 4 days also expressed formin 1, which colocalized with actin microfilaments (Figure 1E). In short, formin 1 was spatiotemporally expressed at the apical ES, limited to the concave (ventral) side of spermatid heads in stage VII tubules (Figure 1F). At the basal ES, formin 1 was also highly expressed consistent with its localization at the BTB near the basement membrane in stage III-VI tubules (Figure 1, D and F), but it was considerably weakened in stage VII and virtually undetectable by stage VIII (Figure 1F). Formin 1 colocalized with TJ adaptor protein zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and basal ES protein N-cadherin at the BTB in stage VI tubules when it was highly expressed (Figure 2A). Formin 1, also highly expressed at the apical ES at stage VII, displayed partial colocalization with apical ES protein β1-integrin, which is restrictively expressed by Sertoli cells (43–46) but not laminin-γ3 which is an apical ES protein limited to elongated spermatids (45, 47, 48) (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Cellular and stage-specific localization of formin 1 in the rat testis. A, Expression of formin 1 in adult rat testes (T), Sertoli cells (SC), and GCs vs ovary (Ov; positive control) were analyzed by RT-PCR with S-16 as a loading PCR control using corresponding specific primer pairs (Supplemental Table 2). M, DNA markers in base pairs. The identity of the PCR product was confirmed by direct nucleotide sequencing. B, Specificity of the antiformin 1 antibody (Supplemental Table 1) was assessed by immunoblotting, using lysates obtained from adult rat testes (T), SC, and GCs with β-actin as a protein loading control. Each bar in the histogram is a mean ± SD of three experiments. Formin 1 protein level in T was arbitrarily set at 1. C, Relative steady-state protein level of formin 1 expressed by Sertoli cells when cultured in vitro for 0–4 days in serum-free F12/DMEM medium with β-actin as a protein loading control. D, Stage-specific localization of formin 1 (green fluorescence) in the seminiferous epithelium of adult rats testes. Cell nuclei were visualized by DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 130 μm. E, Staining of Sertoli cells with antiformin 1 antibody (green fluorescence) and rhodamine phalloidin (red fluorescence) to visualize formin 1 and F-actin, respectively, illustrating partial colocalization of formin 1 and F-actin in Sertoli cell cytosol. Sertoli cell nuclei were visualized by DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 15 μm. F, Stage-specific expression of formin 1 (green fluorescence) and its colocalization with F-actin (red) in the seminiferous epithelium of adult rat testes. Cell nuclei were visualized by DAPI (blue). Formin 1 colocalized with F-actin at the BTB (annotated by yellow arrowheads) and tunica propria at stages III-VI, and formin 1 expression rapidly diminished at stage VII and became virtually nondetectable at stage VIII at the basal ES when the BTB undergoes extensive restructuring to facilitate the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes. However, at the apical ES, formin 1 restrictively expressed at stage VII, colocalizing with F-actin at the concave side of the elongating spermatid. Scale bar, 40 μm; inset, 12 μm.

Figure 2.

Formin 1 is a component of basal and apical ES in the seminiferous epithelium in adult rat testes. A, Dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis illustrated partial colocalization of formin 1 (green fluorescence) with TJ protein ZO-1 (red fluorescence) and basal ES protein N-cadherin (red) at the BTB, most notably at stage VI, and the expression of formin 1 at the basal ES was weakened at stage VII; and at stage VIII, formin 1 was virtually nondetectable at the basal ES during BTB restructuring. Scale bar, 30 μm. B, Formin 1 (green fluorescence) was expressed only at stage VII of the epithelial cycle at the apical ES, and it was partially colocalized with Sertoli cell-specific apical ES protein β1-integrin (red fluorescence) at the concave (ventral) side of spermatid heads because most of β1-integrin expression was restricted to the convex (dorsal) side of spermatid heads. Formin 1, however, was not colocalized with spermatid-specific apical ES protein laminin-γ3 (red fluorescence), which was localized to the spermatid head except its rear end at the apical ES. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Formin 1 interacts with branched actin polymerization-inducing protein Arp3, actin, and tubulin at the ES in adult rat testes

We next examined whether formin 1 interacted with putative apical and basal ES proteins in the testis. By dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis, formin 1 was found to colocalize at the apical ES with both barbed-end nucleation protein Arp3 (16, 49), and actin barbed-end capping and bundling protein Eps8 (17, 50) in stage VII tubules, mostly at the concave side of spermatid heads when these proteins were highly expressed (Figure 3A). At the basal ES, formin 1, however, did not colocalize with Arp3 because the expression of Arp3 was negligible at stage VII, and when Apr3 was expressed at the basal ES at stage VIII, formin 1 expression was virtually undetected (Figure 3A). For Eps8, it partially colocalized with formin 1 at the basal ES at stage VII but not at VIII when both proteins were virtually nondetectable (Figure 3A). Although formin 1 prominently colocalized with both Arp3 and Eps8 at the apical ES in stage VII tubules, a study by Co-IP illustrated that formin 1 structurally associated with Arp3 in the testis, however, neither Eps8 nor other BTB proteins, such as TJ adaptor ZO-1, basal ES protein N-cadherin, and apical ES protein β1-integrin structurally associated with formin 1 (Figure 3B). Formin 1 also structurally interacted with actin as well as α-tubulin, which is a component of the microtubule cytoskeleton (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Formin 1 structurally interacts with branched actin nucleation protein Arp3 and also cytoskeletal proteins actin and α-tubulin. A, At stage VII, formin 1 (green fluorescence) colocalized with actin regulating proteins Arp3 (a branched actin nucleation protein; red fluorescence) (upper panel) and Eps8 (red fluorescence, an actin barbed end capping and bundling protein) (lower panel) at the apical ES in the seminiferous epithelium, at the concave (ventral) side of spermatid heads; formin 1 expression at the basal ES/BTB was already weakened, and Arp3 expression was virtually undetectable, even though Eps8 remained highly expressed. At stage VIII, the expression of formin 1 and Eps8 at the apical ES and basal ES/BTB became undetectable, but the expression of Arp3 was high at the basal ES but none at the apical ES. Scale bar, 40 μm; inset, 12 μm. B, A study by Co-IP to assess the interaction between formin 1 and selected component proteins of the ES and cytoskeletal elements. Rabbit or mouse IgG served as a negative control, and testis lysate without subjected to Co-IP served as a positive control. Formin 1 was found to interact with Arp3 (also confirmed when anti-Arp3 IgG, besides antiformin 1 IgG, was used as an immunoprecipitating antibody), actin, and tubulin but not Eps8. Data shown herein are representative findings of an experiment that was repeated three to four times that yielded similar results. IB, immunoblotting.

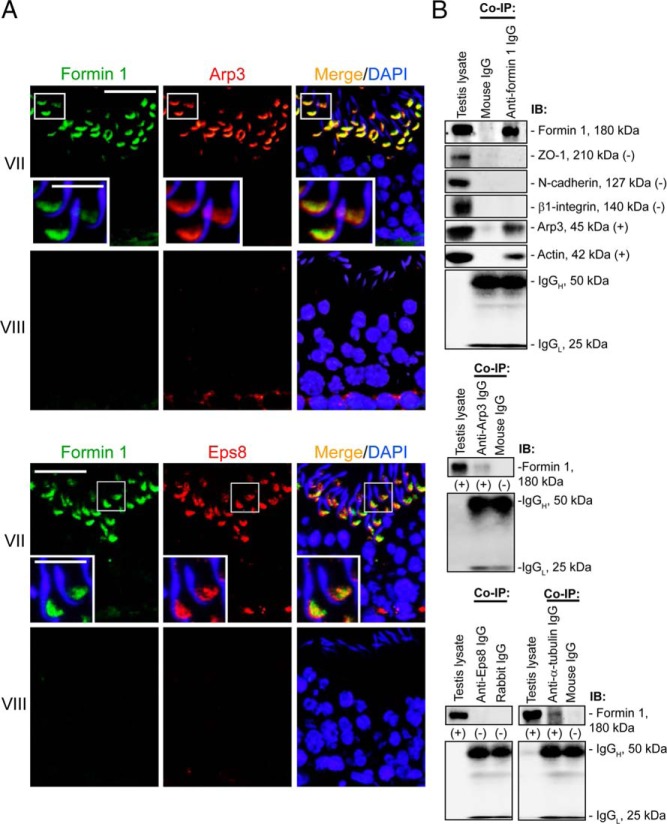

Formin 1 knockdown at the Sertoli cell BTB in vitro perturbs TJ permeability function by altering localization of basal ES proteins

Sertoli cells cultured in vitro for ∼2-day were shown to form a functional TJ-permeability barrier that mimics the BTB in vivo based on functional assay as well as possessing the ultrastructures of TJ, basal ES, gap junction and desmosome when examined by electron microscopy (32, 33). This in vitro model has been widely used by investigators in the field to study BTB function (51–57). This in vitro model to monitor Sertoli cell BTB function was thus used herein. When formin 1 was silenced by RNAi to ∼70% as illustrated by RT-PCR (Figure 4A) and immunoblotting (Figure 4B) without apparent off-target effects since the expression of many of the proteins at the BTB was found to be unaffected (Figure 4B) and without cytotoxicity (Figure 4C), the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier function was shown to be perturbed (Figure 4D). The knockdown of formin 1 in Sertoli cells was further confirmed when the expression of formin 1 in Sertoli cell epithelium was examined by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 4E) and the fluorescence signal was quantified between the formin 1 knockdown vs. control cells (Figure 4F). Interestingly, it was noted that the localization of TJ integral membrane protein occludin and TJ adaptor ZO-1 at the Sertoli cell-cell interface was unaffected after formin 1 knockdown, however, basal ES integral membrane protein N-cadherin and adaptor β-catenin were found to become mislocalized, being weakly localized at the cell-cell interface and apparently internalized (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Knockdown of formin 1 at the Sertoli cell BTB in vitro by RNAi perturbs the TJ permeability barrier function via changes in the localization of basal ES proteins. Sertoli cells cultured for 3 days with an established functional TJ permeability barrier were transfected with rat formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes (Formin 1 siRNA) vs nontargeting negative control (Ctrl siRNA) for 24 hours (ie, d 4). Thereafter cells were washed twice to remove transfection reagents and cultured for additional 24 hours (ie, d 5) before their termination for RNA extraction, cell lysate preparation, or staining with specific antibody. A, Knockdown of formin 1 by formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes at 50 nM vs nontargeting negative controls was examined by RT-PCR. M, DNA marker in base pairs. B, A study by immunoblotting that illustrated the expression of formin 1 was knockdown up to approximately 70% (see also histogram in lower panel) without any apparent off-target effects when other selected BTB-associated proteins were examined. Actin and GAPDH served as protein loading controls. Each bar in the histogram is a mean ± SD of four experiments. **, P < .01. C, Cytotoxicity of siRNA duplexes at varying concentrations on Sertoli cells was examined by sodium 3′-[1-(phenylaminocarbonyl)-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro) benzene sulfonic acid hydrate (XTT) assay on day 5 in cultures with transfection performed on day 3, which monitored cell viability. In short, no cytotoxicity to Sertoli cells was detected at a dose of siRNA duplexes at or less than 200 nM. D, A knockdown of formin 1 was found to perturb the Sertoli cell TJ permeability barrier. Each data point is a mean ± SD of triplicate bicameral units from a representative experiment, which was repeated three times and yielded similar results excluding pilot experiments. *, P < .05. E, A study by IF that confirmed the silencing of formin 1 by approximately 75% (see F, composite data of four experiments; **, P < .01), when the cellular distribution of basal ES proteins N-cadherin and β-catenin, but not TJ proteins occludin and ZO-1, were perturbed in which these proteins no longer tightly localized to the cell-cell interface (annotated by orange arrowheads) but were internalized instead. siGLO red transfection indicator (red fluorescence; Dharmacon) was used to track successful transfection. Scale bar, 15 μm, which applies to other micrographs. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Formin 1 regulates actin microfilament organization in Sertoli cells

The molecular mechanism by which formin 1 knockdown impeded Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function was further investigated. Formin 1 knockdown was found to induce truncation and disorganization of actin microfilaments in Sertoli cells in which microfilaments failed to stretch across the cell, but shorter filaments were scattered throughout the cell cytosol (Figure 5A), plausibly due to mislocalization of Arp3, which is known to effectively induce branched actin polymerization, converting actin microfilaments from a bundled to unbundled/branched configuration (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the localization of actin barbed-end capping and bundling protein Eps8 and actin cross-linking/bundling protein palladin in Sertoli cells was also perturbed after formin 1 knockdown (Figure 5A). For instance, Eps8 was internalized, located more closely to the cell nuclei; and palladin no longer associated with actin microfilaments across the Sertoli cell but became aggregated and distributed in the cell cytosol as noted in three separate experiments (Figure 5A), and the collective changes of these two actin bundling proteins thus impeded the organization of actin microfilaments into a bundled configuration. The findings shown in Figure 5A were further confirmed by biochemical assays that monitored the loss of actin bundling activity in lysates of Sertoli cells following formin 1 knockdown vs cells transfected with nontargeting negative control duplexes (Figure 5B). Also, the actin polymerization capability of Sertoli cells after formin 1 knockdown was also significantly compromised (Figure 5C), supporting the observation shown in Figure 5A depicting a misorganization of actin microfilaments in Sertoli cells.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of formin 1 altered the organization of actin microfilaments in Sertoli cells mediated by changes in the localization of Arp3, Eps8, and palladin. A, Knockdown of formin 1 led to truncation and disorganization of actin microfilaments in Sertoli cells, and many of these microfilaments were shortened and failed to stretch across the entire Sertoli cell. These changes apparently were mediated by changes in the localization of branched actin nucleation protein Arp3 that effectively converted actin microfilaments from a bundled to branched/unbundled configuration. Arp3 was found to be extensively internalized (annotated by orange arrows), which thus induced microfilament branching and truncation in the Sertoli cell cytosol. The actin microfilament barbed-end capping and bundling protein Eps8 as well as the actin cross-linking and bundling protein palladin were also found to be mislocalized in which Eps8 was internalized (annotated by orange arrows); and palladin (green fluorescence) no longer tightly associated with actin microfilaments across the Sertoli cell in the cytosol as noted in controls (see merge image from a different experiment) but appeared as patches of aggregates (annotated by orange arrows), thereby failing to confer actin microfilaments into a bundled configuration as noted in control cells. siGLO red transfection indicator (red fluorescence; Dharmacon) was used to track successful transfection. Scale bar, 15 μm, which applies to other micrographs. B, A study by biochemical assay to confirm findings shown in panel A by assessing actin bundling activity (top panel) after formin 1 knockdown (lower panel), in which the pellet contained bundled actin microfilaments, whereas S/N (supernatant) contained single (ie, unbundled) actin microfilaments. Findings shown on the upper panel are summarized in the histogram on the lower panel with each bar represents a mean ± SD of four experiments. *, P < .05. C, Knockdown of formin 1 was also found to perturb actin polymerization after formin 1 knockdown (upper panel). The kinetics of actin polymerization was assessed during the initial 8 minutes of the actin polymerization assay (see lower panel) using data shown on the upper panel (see Materials and Methods for details), illustrating the knockdown of formin 1 indeed perturbed actin polymerization kinetics, with each bar representing a mean ± SD of three experiments. *, P < .05. Ctrl, control.

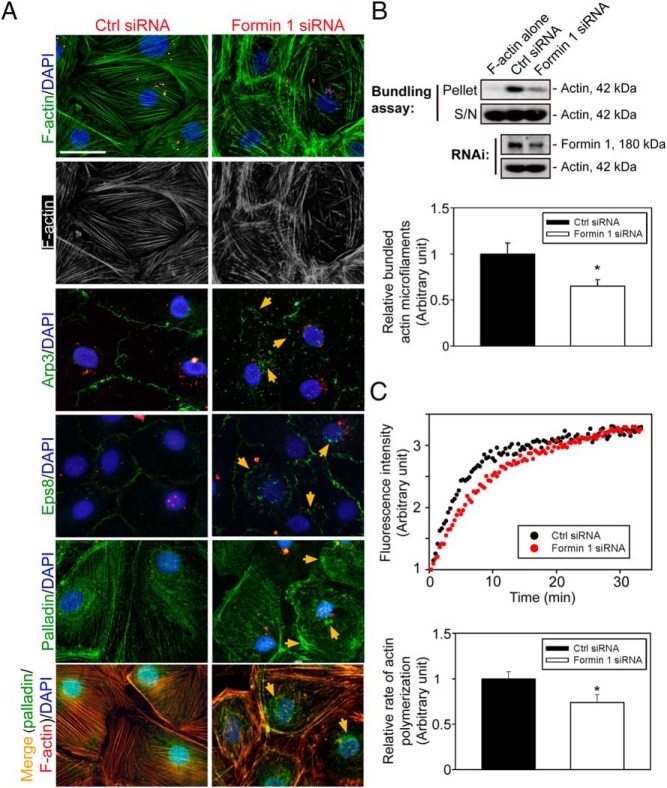

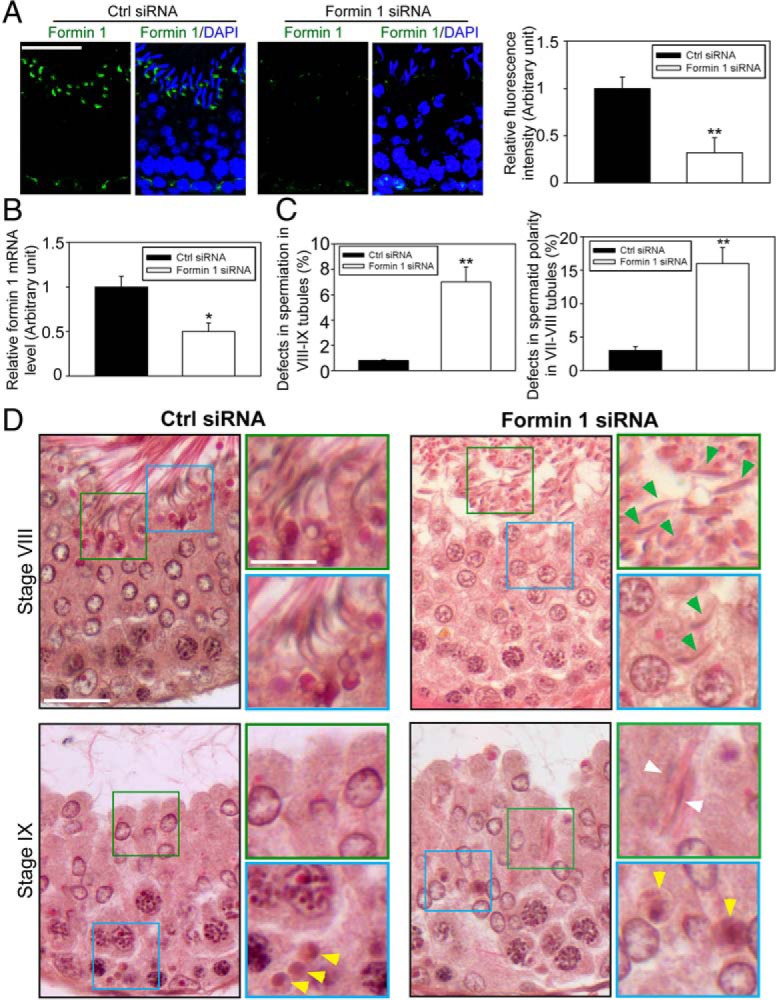

Formin 1 knockdown in the testis in vivo perturbs spermatogenesis

To further examine the physiological relevancy of findings in vitro, formin 1 was silenced in the testis in vivo by RNAi (Figure 6A). Because formin 1 was notably expressed at the apical ES and moderately at the basal ES in stage VII tubules, but also prominently at the basal ES in stage III-VI tubules (Figure 1), the fluorescence signals of formin 1 in these tubules between formin 1 knockdown and control testes were compared, and an approximately 70% knockdown of formin 1 signal was observed (Figure 6A), which is consistent with data obtained by quantitative PCR (Figure 6B). When the status of spermatogenesis in these rat testes was examined, the most notable phenotypes that were detected were as follows: 1) defects in spermiation in which more than five elongated spermatids were found to be embedded inside the seminiferous epithelium in stage VIII or IX tubules when spermiation had occurred (Figure 6C), and 2) defects in spermatid polarity in which more than five misoriented elongated spermatids were found to have their heads no longer pointed toward the basement membrane but deviated by at least 90° from their intended orientation in stage VII-VIII tubules (Figure D). Also, phagosomes were found to fail to be transported to the basal compartment near the basement membrane in stage IX (Figure 6D) when this should have occurred (58) as shown in control testes (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Knockdown of formin 1 in the testis in vivo perturbs spermatid adhesion and polarity in the seminiferous epithelium. Testes of adult rats (∼70 dpp, day postpartum, ∼325–350 g body weight) were transfected with formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes vs nontargeting negative controls on days 0, 1, and 2; and rats were euthanized on day 5 (n = 6 rats). Thereafter testes were collected, one of the two testes from each rat was frozen in liquid nitrogen for lysate preparation and RNA extraction) or to obtain frozen sections for immunofluorescence analysis (IF) (ie, n = 3 testes from 3 rats), and the other testis was fixed in Bouin's fixative to obtain paraffin sections for histological analysis (ie, n = 3 testes from three rats). A, Frozen sections of testes from both groups were stained for formin 1 (green), cell nuclei were visualized with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 40 μm, which applies to other micrographs. Due to the stage-specific expression of formin 1 at the apical ES in stage VII tubules, we focused our analysis on this stage. At least 30 stage VII tubules of each testis from formin 1 knockdown group (n = 3 rats) vs control group (n = 3 rats) were analyzed (see histogram on the right panel, with each bar represents a mean ± SD of three rats in which formin 1 fluorescence signal was considerably diminished after formin 1 knockdown in vivo; **, P < .01). B, The steady-state formin 1 mRNA level in the testis of formin 1 knockdown vs control groups was examined by quantitative PCR, with GAPDH serving as a loading and PCR control. The mRNA level of formin 1 was reduced by at least 50% in the testis in vivo in the formin 1 vs nontargeting control group with three rats for each group; *, P < .05. C, Stage VIII-IX tubules displaying defects of spermiation was scored (∼30 VIII-IX tubules per testis were randomly scored with three rats with a total of ∼100 tubules). A tubule was scored to have defects in spermiation wherein more than five elongated spermatids per cross-section of a tubule were found to be embedded inside the seminiferous epithelium that failed to undergo spermiation. Stage VII-VIII tubule was scored when more than five spermatids lose their polarity and considered to have defects in spermatid polarity. Data were expressed as percentage of stage VII-IX tubules with defects in both groups; **, P < .01. D, Histological analysis of cross-sections of testes in both groups in stage VIII and IX tubules. Control testes were transfected with nontargeting negative control siRNA duplexes (left panel) vs formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes (right panel). Defects in spermiation were noted in formin 1 knockdown testes at both stage VIII and also IX tubules in which spermatids were entrapped inside the epithelium (annotated by white arrowheads) and many spermatids were found to lose their polarity in which spermatid heads no longer pointing toward the basement membrane but deviated at 90° from the intended orientation (annotated by green arrowheads). Boxed areas in green or blue was magnified and shown in insets. Scale bar, 40 μm; inset, 12 μm. Ctrl, control.

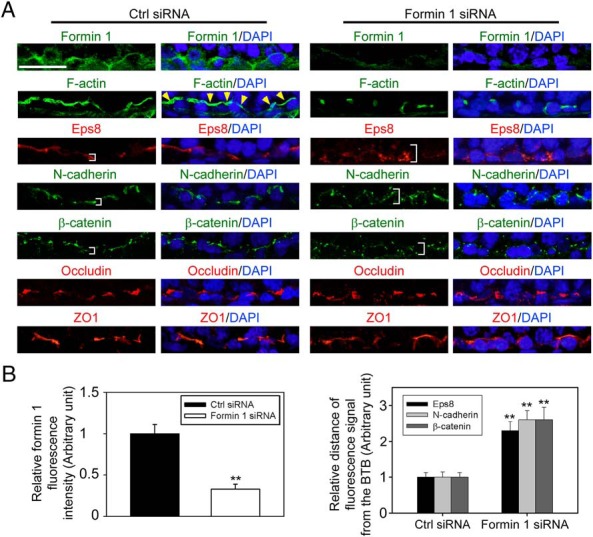

Formin 1 knockdown in the testis in vivo perturbs the localization of basal ES proteins at the BTB

In stage VI-early VII tubules when formin 1 expression at the basal ES was high, transfection of testes with formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes effectively silenced formin 1 expression (Figure 7A) by approximately 70% (Figure 7B). This formin 1 knockdown also perturbed the organization of F-actin at the BTB in which F-actin no longer formed a continuous belt-like ultrastructure but became truncated (Figure 7A), and this is likely due to a mislocalization of actin barbed-end capping and bundling protein Eps8 by diffusing away from the BTB, thereby failing to maintain a proper organization of actin microfilaments to support F-actin network at the site (Figure 7, A and B) (note: we did not investigate Arp3 localization because Arp3 was not expressed at the BTB in stage VI-VII tubules) (Figure 3A) (16). This disruptive effect on the F-actin network at the BTB thus impeded the organization of basal ES protein N-cadherin and β-catenin (Figure 7A, B). However, TJ proteins occludin and ZO-1 were not affected (Figure 7A), consistent with the in vitro findings of Figure 4E.

Figure 7.

Knockdown of formin 1 in adult rat testes in vivo perturbs the distribution of F-actin, actin regulatory proteins, and basal ES proteins at the BTB. A, Testes transfected with formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes vs nontargeting negative control duplexes were used to obtain frozen sections and stained for formin 1 (green fluorescence), F-actin (green fluorescence), actin barded-end capping and bundling protein Eps8 (red fluorescence), basal ES proteins N-cadherin (green fluorescence) and β-catenin (green fluorescence), and TJ proteins occludin (red fluorescence) and ZO-1 (red fluorescence). Cell nuclei were visualized with DAPI (blue). Because formin 1 was highly expressed at the basal ES/BTB in stage VI tubules, considerably diminished in stage VII tubules, and virtually nondetectable in stage VIII tubules, this analysis was performed in stage VI tubules. Expression of formin 1 became considerably diminished at the BTB in stage VI tubules after formin 1 silencing vs controls. In control testes, F-actin was prominently expressed and appeared as a continuous belt surrounding the BTB (see yellow arrowheads), after formin 1 knockdown, and F-actin no longer surrounded the BTB continuously but appeared broken into fragments. This is likely due to the mislocalization of Eps8, which no longer tightly localized to the BTB (see white brackets). This misorganization of F-actin then impeded the distribution of basal ES proteins N-cadherin and β-catenin because these adhesion proteins also localized diffusely from the BTB (see white brackets) after formin 1 knockdown vs testes transfected with nontargeting negative control duplexes (right panel). Scale bar, 30 μm, which applies to other micrographs. B, Composite data of findings shown in panel A in which each bar represents a mean ± SD three testes, illustrating the knockdown of formin 1 (left panel) perturbed the localization of Eps8, N-cadherin, and β-catenin at the BTB; **, P < .01. Ctrl, control.

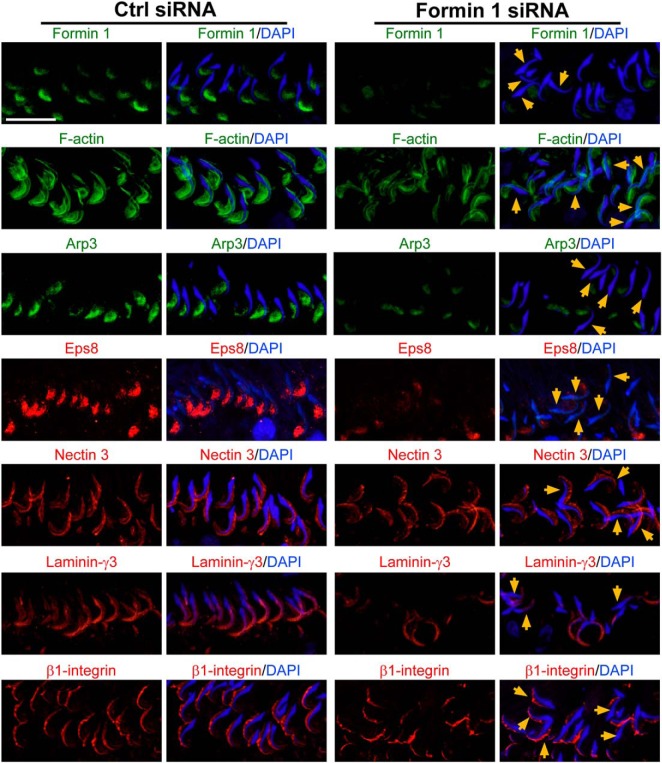

Formin 1 knockdown perturbs the localization of apical ES proteins that leads to defects in spermiation and spermatid polarity

We next examined changes in the distribution of apical ES proteins in the testis following knockdown of formin 1 (Figure 8) to gain some insights regarding the noted defects in spermiation and spermatid polarity shown in Figure 6, C and D, in formin 1-silenced testes. It was noted that F-actin organization at the apical ES was compromised after formin 1 knockdown because F-actin that was found to cover both the convex and concave side of spermatid heads had considerably diminished, in particular at the concave side (Figure 8). This is likely due to the mislocalization and/or down-regulation of Arp3 and Eps8, in particular in spermatids with defects in polarity (Figure 8). Although the localization of nectin 3 at the apical ES was not grossly affected, the localization and expression of laminin-γ3 chain and β1-integrin, however, were considerably affected (Figure 8). For instance, laminin-γ3 no longer covered the entire tip of spermatid heads, and β1-integrin was either truncated or absent from the convex side of spermatid heads at the apical ES in formin 1-silenced testes (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Knockdown of formin 1 in adult rat testes in vivo perturbs the distribution of F-actin, actin regulatory proteins, and apical ES proteins, leading to defects in spermatid polarity and spermiation. Testes transfected with formin 1-specific siRNA duplexes (Formin 1 siRNA) vs nontargeting negative control duplexes (Ctrl siRNA) were used to obtain frozen sections and stained for formin 1 (green fluorescence), F-actin (green fluorescence), actin barbed-end nucleation protein Arp3 (green fluorescence), actin barbed-end capping and bundling protein Eps8 (red fluorescence), and apical ES proteins nectin 3 (red fluorescence), laminin-γ3 (red fluorescence), and β1-integrin (red fluorescence). Cell nuclei were visualized with DAPI (blue). Because formin 1 was highly expressed at the apical ES, mostly at the concave (ventral) side of spermatid heads, in stage VII tubules, this analysis was performed using VII tubules. After formin 1 knockdown, the expression of formin 1 at the apical ES was considerably diminished, and many spermatids had lost their polarity in which their heads no longer pointed toward the basement membrane but deviated by at least 90° from the intended orientation (annotated by orange arrows). F-actin no longer tightly localized surrounding both the concave (ventral) and convex (dorsal) side of spermatid heads as shown in control testes but limited mostly to the tip of spermatid heads. The defects in F-actin organization at the apical ES is likely the result of mislocalization of Arp3 and Eps8 in these stage VII tubules, which thus contributed to the mislocalization of apical ES adhesion proteins nectin 3 and laminin-γ3 (both of which are spermatid specific proteins) but also Sertoli cell-specific apical ES protein β1-integrin. These defects thus perturbed spermatogenesis as illustrated in Figure 6, such as defects in spermiation in which spermatids were found to be embedded in the seminiferous epithelium in stage VIII and IX tubules due to defects in spermatid adhesion as a result of F-actin microfilament reorganization at the apical ES. Scale bar, 30 μm, which applies to other micrographs. Ctrl, control.

Discussion

Formins, such as formin 1, when activated by Rho GTPases, two identical polypeptides, are dimerized via their formin homology 2 domains, creating a functional protein dimer that in turn interacts with other nucleation cofactors and profilin-actin complexes near the C-terminal tail regions mediated by the formin homology 1 domain (59, 60) to promote the nucleation of actin microfilaments by the progressive addition of actin monomers onto the plus end of a growing actin filament (20, 26, 61). Formin 1, similar to other formins, can remain attached to growing ends of actin microfilaments, such as for minutes without dissociation, to produce long stretches of filaments (62–64), and because its formin homology 2 domain also confers F-actin bundling activity (26), microfilaments generated by formin 1 can be rapidly bundled for the assembly of apical ES during spermiogenesis to facilitate the adhesion, transport, and polarity of spermatids or basal ES during remodeling of the BTB to facilitate the transport of preleptotene spermatocytes. Interestingly, while formin 1 is intensively expressed at the interface between Sertoli cells and step 19 spermatids, it is limited only to stage VII tubules because virtually no formin 1 is detected at the apical ES in any other stages of the epithelial cycle. These findings thus suggest that, although formin 1 is an important actin nucleation protein to create actin microfilaments necessary to confer actin filament bundles at the apical ES, its physiological function is limited to stage VII tubules, suggesting other actin nucleation proteins, such as other formins and perhaps Wiskott Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-homology 2 domain-containing proteins (eg, Spir) (65, 66) may be involved in conferring actin microfilament bundles at the apical ES in other stages of the cycle.

Studies have shown that at stage VII, apical ES undergoes extensive remodeling by endocytic vesicle-mediated trafficking involving endocytosis, transcytosis, and/or recycling, creating an ultrastructure known as apical tubulobulbar complex (TBC) (6, 8, 15, 67), which is a transitional ultrastructure of the apical ES prior to its breakdown/degeneration at spermiation (12). Furthermore, proteins pertinent to these events such as neuronal WASP (N-WASP), cortactin, and clathrin are abundantly expressed at the apical TBC (68), and they are involved in endocytic vesicle-mediated protein trafficking at the TBC (69, 70). Utilizing TBC, old apical ES proteins can be recycled to form new apical ES that is assembled when step 8 spermatids arise at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle (12), in addition to its use to eliminate unwanted cytoplasmic debris from the head region of late spermatids during spermiogenesis (8, 71). In this context, it is of interest to note that both actin regulatory proteins Arp3 and Eps8 are also abundantly expressed and colocalized with formin 1 at the apical ES/apical TBC site as reported herein. Thus, Arp3, Eps8 and formin 1 are necessary to confer apical ES function at stage VII of the epithelial cycle, and it appears that formin 1 is pivotal to coordinate the function of these two other actin regulatory proteins. This notion is supported by findings in vivo when formin 1 expression was silenced by RNAi. It is reported that apical ES confers spermatid adhesion, transport, and polarity (14, 72, 73). A knockdown of formin 1 was found to compromise apical ES function by perturbing spermatid transport and adhesion, leading to retention of late spermatids into the epithelium in late stage VIII and IX tubules, causing defects in spermatid polarity. More important, a knockdown of formin 1 also led to defects in the spatiotemporal localization and/or expression of Arp3 and Eps8 at the apical ES in stage VII tubules, supporting the notion that formin 1 may play a role in coordinating the function of Arp2/3 complex and Eps8 at the ES.

Changes in the apical ES function based on studies in vivo as summarized above may stem from a disruption in the organization of actin microfilaments at the ES after formin 1 knockdown. This concept is supported by studies in vitro at the basal ES in the Sertoli cell epithelium. Morphologically, basal ES coexists with TJ, which together with gap junction and desmosome create the BTB (3, 12); thus, actin microfilaments at the basal ES is crucial to confer the integrity of the Sertoli cell BTB. As reported herein, a knockdown of formin 1 by RNAi caused truncation in actin microfilaments in Sertoli cells, unable to form undisrupted polarized actin microfilaments across the cell cytosol to support basal ES adhesion proteins vs control cells. This observation is also supported by biochemical assays in which both the actin polymerization activity and bundling capability were considerably diminished following formin 1 knockdown, consistent with the reported function of formin 1 by conferring actin nucleation/polymerization and bundling because formin 1 has intrinsic F-actin bundling activity in addition to promoting actin nucleation (20, 26). Thus, basal ES protein N-cadherin and β-catenin no longer localized properly to the Sertoli cell-cell interface, thereby impeding TJ-barrier function.

In this context, it is of interest to note that the expression of formin 1 at the basal ES is not limited to stage VII of the epithelial cycle. Instead, formin 1 is prominently expressed at the basal ES/BTB in stage III-VI tubules, diminished considerably at stage VII, and virtually nondetectable by stage VIII, illustrating there is differential expression of formin 1 at the basal ES vs apical ES. Nonetheless, formin 1 exerts its function at the basal ES by maintaining the network of actin microfilament bundles at the BTB, possibly mediated via its spatiotemporal expression during the epithelial cycle. For instance, its knockdown in the testis in vivo also perturbs the spatiotemporal localization of basal ES proteins N-cadherin and β-catenin at the BTB, consistent with the findings in vitro. The upstream signaling molecule(s) that regulate the stage-specific and differential expression of formin 1 at the apical vs the basal ES during spermatogenesis remain to be identified. However, our findings illustrate that formin 1 is working in concert with the Arp2/3 complex, Eps8, and palladin to regulate actin organization. We did not assess the fertility status of the formin 1 knockdown rats, but based on the morphological analysis, the formin 1 knockdown rats are likely fertile because other formins may supersede the lost function of formin 1 in the testis.

In summary, formin 1 is a regulator of actin microfilaments at the ES that confers Sertoli and germ cell adhesion, spermatid transport, and spermatid polarity during spermatogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grants U54 HD029990 (Project 5 to C.Y.C.) and R01 HD056034 (to C.Y.C.); National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC)/Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (RGC) Joint Research Scheme, Grant N_HKU 717/12 (to W.M.L.), General Research Fund 771513 of Hong Kong Research Grants Council (to W.M.L.), and University of Hong Kong Committee on Research and Conference Grants (GRCG) Seed Funding (to W.M.L.); and Hong Kong Baptist University Strategy Development Fund (SDF11-1215-P07) (to C.K.C.W.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- Arp2/3

- actin-related protein 2/3

- Arp3

- actin-related protein 3

- BTB

- blood-testis barrier

- Co-IP

- coimmunoprecipitation

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- Eps8

- epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8

- ES

- ectoplasmic specialization

- GC

- germ cell

- IF

- immunofluorescence analysis

- N-WASP

- neuronal WASP

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- SC

- Sertoli cell

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TBC

- tubulobulbar complex

- TJ

- tight junction

- WASP

- Wiskott Aldrich syndrome protein

- ZO-1

- zonula occludens-1.

References

- 1. Franca LR, Auharek SA, Hess RA, Dufour JM, Hinton BT. Blood-tissue barriers: Morphofunctional and immunological aspects of the blood-testis and blood-epididymal barriers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;763:237–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pelletier RM. The blood-testis barrier: the junctional permeability, the proteins and the lipids. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2011;46:49–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng CY, Mruk DD. The blood-testis barrier and its implication in male contraception. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:16–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hess RA, de Franca LR. Spermatogenesis and cycle of the seminiferous epithelium. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;636:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Kretser DM, Kerr JB. The cytology of the testis. In: Knobil E, Neill JB, Ewing LL, Greenwald GS, Markert CL, Pfaff DW, eds. The Physiology of Reproduction. Vol 1 New York: Raven Press; 1988:837–932. [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Donnell L, Nicholls PK, O'Bryan MK, McLachlan RI, Stanton PG. Spermiation: the process of sperm release. Spermatogenesis. 2011;1:14–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Biochemistry of Sertoli cell/germ cell junctions, germ cell transport, and spermiation in the seminiferous epithelium. In: Griswold MD, ed. Sertoli Cell Biology. 2nd ed Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015:333–383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-417047-6.00012-0. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vogl AW, Young JS, Du M. New insights into roles of tubulobulbar complexes in sperm release and turnover of blood-testis barrier. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013;303:319–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vogl AW, Vaid KS, Guttman JA. The Sertoli cell cytoskeleton. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;636:186–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Russell LD, Peterson RN. Sertoli cell junctions: morphological and functional correlates. Int Rev Cytol. 1985;94:177–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Cell junction dynamics in the testis: Sertoli-germ cell interactions and male contraceptive development. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:825–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheng CY, Mruk DD. A local autocrine axis in the testes that regulates spermatogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:380–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Russell LD, Saxena NK, Turner TT. Cytoskeletal involvement in spermiation and sperm transport. Tissue Cell. 1989;21:361–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Sertoli-Sertoli and Sertoli-germ cell interactions and their significance in germ cell movement in the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:747–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qian X, Mruk DD, Cheng YH, et al. Actin binding proteins, spermatid transport and spermiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lie PPY, Chan AYN, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Restricted Arp3 expression in the testis prevents blood-testis barrier disruption during junction restructuring at spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11411–11416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lie PPY, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8) is a novel regulator of cell adhesion and the blood-testis barrier integrity in the seminiferous epithelium. FASEB J. 2009;23:2555–2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qian X, Mruk DD, Wong EWP, Lie PPY, Cheng CY. Palladin is a regulator of actin filament bundles at the ectoplasmic specialization in the rat testis. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1907–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goode BL, Eck MJ. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:593–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Breitsprecher D, Goode BL. Formins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Campellone KG, Welch MD. A nucleator arms race: cellular control of actin assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kobielak A, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Mammalian formin-1 participates in adherens junctions and polymerization of linear actin cables. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Woychik RP, Maas RL, Zeller R, Vogt TF, Leder P. ‘Formins’: proteins deduced from the alternative transcripts of the limb deformity gene. Nature. 1990;346:850–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zeller R, Haaramis AG, Zuniga A, et al. Formin defines a large family of morphoregulatory genes and functions in establishment of the polarising region. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nurnberg A, Kitzing T, Grosse R. Nucleating actin for invasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bohnert KA, Willet AH, Kovar DR, Gould KL. Formin-based control of the actin cytoskeleton during cytokinesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1750–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mruk DD, Cheng CY. An in vitro system to study Sertoli cell blood-testis barrier dynamics. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;763:237–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Galdieri M, Ziparo E, Palombi F, Russo MA, Stefanini M. Pure Sertoli cell cultures: a new model for the study of somatic-germ cell interactions. J Androl. 1981;2:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee NPY, Mruk DD, Conway AM, Cheng CY. Zyxin, axin, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein are adaptors that link the cadherin/catenin protein complex to the cytoskeleton at adherens junctions in the seminiferous epithelium of the rat testis. J Androl. 2004;25:200–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aravindan GR, Pineau C, Bardin CW, Cheng CY. Ability of trypsin in mimicking germ cell factors that affect Sertoli cell secretory function. J Cell Physiol. 1996;168:123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pineau C, Syed V, Bardin CW, Jegou B, Cheng CY. Germ cell conditioned medium contains multiple factors that modulate the secretion of testin, clusterin, and transferrin by Sertoli cells. J Androl. 1993;14:87–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lie PPY, Cheng CY, Mruk DD. Cross talk between desmoglein-2/desmocollin-2/Src kinase and coxsackie and adenovirus receptor/ZO-1 protein complexes, regulates blood-testis barrier dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:975–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li MWM, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Disruption of the blood-testis barrier integrity by bisphenol A in vitro: Is this a suitable model for studying blood-testis barrier dynamics? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:2302–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tang EI, Mok KW, Lee WM, Cheng CY. EB1 regulates tubulin and actin cytoskeletal networks at the Sertoli cell blood-testis barrier in male rats—an in vitro study. Endocrinology. 2015;156:680–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lie PPY, Mruk DD, Mok KW, Su L, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Focal adhesion kinase-Tyr407 and -Tyr397 exhibit antagonistic effects on blood-testis barrier dynamics in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12562–12567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wan HT, Mruk DD, Wong CKC, Cheng CY. Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) perturbs male rat Sertoli cell blood-testis barrier function by affecting F-actin organization via p-FAK-Tyr407—an in vitro study. Endocrinology. 2014;155:249–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su WH, Wong EWP, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. The Scribble/Lgl/Dlg polarity protein complex is a regulator of blood-testis barrier dynamics and spermatid polarity during spermatogenesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153:6041–6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) for routine immunoblotting. An inexpensive alternative to commercially available kits. Spermatogenesis. 2011;1:121–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Su L, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Regulation of the blood-testis barrier by coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR). Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C843–C853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xiao X, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. c-Yes regulates cell adhesion at the blood-testis barrier and the apical ectoplasmic specialization in the seminiferous epithelium of rat testes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:651–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parvinen M. Regulation of the seminiferous epithelium. Endocr Rev. 1982;3:404–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xiao X, Mruk DD, Wong CKC, Cheng CY. Germ cell transport across the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Physiology. 2014;29:286–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Palombi F, Salanova M, Tarone G, Farini D, Stefanini M. Distribution of β1 integrin subunit in rat seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1992;47:1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Salanova M, Stefanini M, De Curtis I, Palombi F. Integrin receptor α6β1 is localized at specific sites of cell-to-cell contact in rat seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Siu MKY, Cheng CY. Interactions of proteases, protease inhibitors, and the β1 integrin/laminin γ3 protein complex in the regulation of ectoplasmic specialization dynamics in the rat testis. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:945–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mulholland DJ, Dedhar S, Vogl AW. Rat seminiferous epithelium contains a unique junction (ectoplasmic specialization) with signaling properties both of cell/cell and cell/matrix junctions. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:396–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Koch M, Olson P, Albus A, et al. Characterization and expression of the laminin γ3 chain: a novel, non-basement membrane-associated, laminin chain. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:605–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yan HHN, Cheng CY. Laminin α3 forms a complex with β3 and γ3 chains that serves as the ligand for α6β1-integrin at the apical ectoplasmic specialization in adult rat testes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17286–17303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Edwards M, Zwolak A, Schafer DA, Sept D, Dominguez R, Cooper JA. Capping protein regulators fine-tune actin assembly dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:677–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ahmed S, Goh WI, Bu W. I-BAR domains, IRSp53 and filopodium formation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Janecki A, Jakubowiak A, Steinberger A. Effect of cadmium chloride on transepithelial electrical resistance of Sertoli cell monolayers in two-compartment cultures—a new model for toxicological investigations of the “blood-testis” barrier in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;112:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Okanlawon A, Dym M. Effect of chloroquine on the formation of tight junctions in cultured immature rat Sertoli cells. J Androl. 1996;17:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nicholls PK, Harrison CA, Gilchrist RB, Farnworth PG, Stanton PG. Growth differentiation factor 9 is a germ cell regulator of Sertoli cell function. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2481–2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaitu'u-Lino TJ, Sluka P, Foo CF, Stanton PG. Claudin-11 expression and localisation is regulated by androgens in rat Sertoli cells in vitro. Reproduction. 2007;133:1169–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Du M, Young J, De Asis M, et al. A novel subcellular machine contributes to basal junction remodeling in the seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Qiu L, Zhang X, Zhang X, et al. Sertoli cell is a potential target for perfluorooctane sulfonate-induced reproductive dysfunction in male mice. Toxicol Sci. 2013;135:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen J, Fok KL, Chen H, Zhang XH, Xu WM, Chan HC. Cryptorchidism-induced CFTR down-regulation results in disruption of testicular tight junctions through up-regulation of NF-κB/COX-2/PGE2. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:2585–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Clermont Y, Morales C, Hermo L. Endocytic activities of Sertoli cells in the rat. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1987;513:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Paul AS, Pollard TD. The role of the FH1 domain and profilin in formin-mediated actin-filament elongation and nucleation. Curr Biol. 2008;18:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Paul AS, Pollard TD. Review of the mechanism of processive actin filament elongation by formins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2009;66:606–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kuhn S, Geyer M. Formins as effector proteins of Rho GTPases. Small GTPases. 2014;5:e29513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Neidt EM, Skau CT, Kovar DR. The cytokinesis formins from the nematode worm and fission yeast differentially mediate actin filament assembly. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23872–23883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kovar DR, Harris ES, Mahaffhy R, Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Control of the assembly of ATP- and ADP-actin by formins and profilin. Cell. 2006;124:423–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Breitsprecher D, Jaiswal R, Bombardier JP, Gould CJ, Geelles J, Goode BL. Rocket launcher mechanism of collaborative actin assembly defined by single-molecule imaging. Science. 2012;336:1164–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dietrich S, Weiβ S, Pleiser S, Kerkhoff E. Structural and functional insights into the Spir/formin actin nucleator complex. Biol Chem. 2013;394:1649–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kerkhoff E. Actin dynamics at intracellular membranes: the Spir/formin nucleator complex. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:922–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Russell LD. Further observations on tubulobulbar complexes formed by late spermatids and Sertoli cells in the rat testis. Anat Rec. 1979;194:213–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Young JS, Guttman JA, Vaid KS, Vogl AW. Cortactin (CTTN), N-WASP (WASL), and clathrin (CLTC) are present at podosome-like tubulobulbar complexes in the rat testis. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Young JS, Takai YK, Kojic KL, Vogl AW. Internalization of adhesion junction proteins and their association with recycling endosome marker proteins in rat seminiferous epithelium. Reproduction. 2012;143:347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Young JS, Vogl AW. Focal adhesion proteins zyxin and vinculin are co-distributed at tubulobulbar complexes. Spermatogenesis. 2012;2:63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Russell LD. Spermatid-Sertoli tubulobulbar complexes as devices for elimination of cytoplasm from the head region in late spermatids of the rat. Anat Rec. 1979;194:233–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wong EWP, Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Biology and regulation of ectoplasmic specialization, an atypical adherens junction type, in the testis. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:692–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vogl A, Pfeiffer D, Mulholland D, Kimel G, Guttman J. Unique and multifunctional adhesion junctions in the testis: ectoplasmic specializations. Arch Histol Cytol. 2000;63:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]