Abstract

Background

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) protects cells by anti-oxidation, maintaining normal microcirculation and anti-inflammatory under stress. This study investigated the effects of biliary tract external drainage (BTED) on the expression levels of HO-1 in rat livers.

Methods

Biliary tract external drainage was performed by inserting a cannula into the bile duct. Sixty Sprague–Dawley rats were randomized to the following groups: sham 1 h group; BTED 1 h group; bile duct ligation (BDL) 1 h group; sham 6 h group and BTED 6 h group. The expression levels of HO-1 mRNA were analyzed using real-time RT-PCR. The expression levels of HO-1 were analyzed using immunohistochemistry.

Results

The expression levels of HO-1 mRNA in the liver of the BTED group increased significantly compared with the sham group 1 and 6 h after surgery (p < 0.05).The expression levels of HO-1 in the BTED group increased significantly compared with the sham group 1 and 6 h after surgery. The expression levels of HO-1 mRNA in the liver in the BDL group decreased significantly compared with the sham group 1 h after surgery (p < 0.05).The expression levels of HO-1 in the BDL group decreased significantly compared with the sham group at this time.

Conclusion

Biliary tract external drainages increase the expression levels of HO-1 in the liver.

Keywords: Biliary tract external drainage, Heme oxygenase-1

Background

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) protects cells by anti-oxidation, maintaining normal microcirculation and anti-inflammatory under stress. Four decades of research have witnessed the HO-1 system continues to fascinate researchers across many areas of basic and clinical sciences [1, 2]. Bilirubin may play an negative feedback on the formation of HO-1 according to this theory. We speculate that biliary tract external drainage (BTED) may induce compensatory increase in HO-1 expression via blocking the enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin. Therefore, we explored effects of BTED on HO-1 expression in the liver.

Methods

Animal model

Sixty adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–300 g) were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Ruijin Hospital. Rats were housed and fed in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animal Resources approved by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Medicine School Animal Care and Ethics Committee.

After a 1-week adaption period during which food and water were available ad libitum, rats were randomly divided into 5 groups: sham 1 h group; BTED 1 h group; bile duct ligation (BDL) 1 h group; sham 6 h group and BTED 6 h group. Rats were fasted overnight prior to experiments, but water was available ad libitum. Rats in the BTED group were intraperitoneally anesthetized with 3% sodium pentobarbital (0.2 ml/100 g). Laparotomies were performed after shaving and sterilization. Bile duct was exposed long enough for BTED. A catheter (inner diameter 0.4 mm; outer diameter 0.8 mm; length 20 cm) was inserted into the bile duct. The distal end of bile duct was ligated. The catheter was passed through the flank of rats to avoid bile passage into the gut and allow for the external collection of bile. In the BDL group, the bile duct was ligated. The abdomen was closed subsequently. Rats in the BDL group underwent pentobarbital anesthesia, laparotomy, bile duct ligation and suture. Rats in the sham group underwent pentobarbital anesthesia, laparotomy and suture. Twelve rats in every group were sacrificed at the point of setting time. Livers were collected.

The expression levels of HO-1 messenger RNA (mRNA) in the liver

Liver scrapings from all animals were snap frozen and stored at −80°C for real-time RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from the liver using TRIzol reagent. Aliquots (2 μg) of total RNA were used to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA). Purity and content of RNA was determined using ultraviolet spectrophotometry. A reverse transcription reaction was conducted in a mixture containing random primers, Revert Aid Reverse Transcriptase, RNase inhibitor, and dNTPs. The PCR reaction mixture was prepared using an SYBR Premix Ex Taq with specific upstream and downstream primers. The thermal cycling conditions were 10 s at 95°C for the initial denaturation step followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 20 s in a real-time PCR system (7500, ABI, Foster, USA). The mRNA levels of HO-1 are expressed relative to the sham rats using the ΔΔCt method. The primers for HO-1 were 5′-ACCCCACCAAGTTCAAACAG-3′ and 5′-GAGCAGGAAGGCGGT-CTTAG-3′. The primers for β-actin were 5′-GCGCTCGTCGTCGACAACGG-3′ and 5′-GTGTGGTGCCAAATCTTCTCC-3′.

Immunohistochemistry

Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 µm. Sections were mounted onto APES-coated slides, deparaffinized, rehydrated, incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide to quench any endogenous peroxidase activity, and washed with distilled water and PBS for 5 min. Sections were placed in 3% citrate buffer to repair antigens. The buffer was heated to a temperature of 92–98°C using a microwave and maintained at that temperature for 10 min. The sections were cooled to room temperature. A 10% nonimmune goat serum was applied to eliminate nonspecific staining. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with optimally diluted primary antibody. Primary antibody used for immunohistochemistry was a rabbit polyclonal to HO-1 (1:200). Sections were washed with PBS and incubated with a broad-spectrum second antibody for 30 min, rewashed, and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin for 15 min. Peroxidation activity was visualized via incubation with a peroxidase substrate solution (DAB kit). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Reagents

TRIzol lysate was purchased from the Invitrogen Company (Frederick, USA), The revertAid first stand cDNA synthesis kit was purchased from the Thermo Company (Lithuania, EU), the Fluorescence quantitative RT-PCR kit was purchased from the Takara Company (Dalian, China), the HO-1 primers were synthesized by the Invitrogen Company (Shanghai, China), the anti-heme oxygenase 1 antibody was purchased from the Abcam Company (Cambridge, MA, USA), the immunohistochemistry kit was purchased from the Invitrogen Company (Frederick, USA).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 software. All data are expressed as mean ± SE of mean values, and results were compared using the unpaired Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s test. A p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Effects of BTED on the expression levels of HO-1 mRNA in the liver

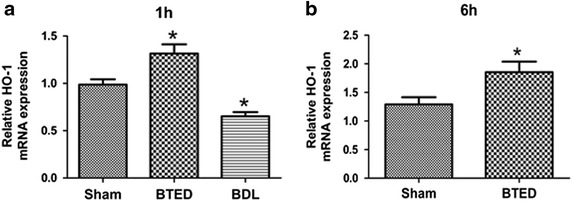

The expression levels of HO-1 mRNA in the liver of the BTED group increased significantly compared with the sham group 1 h after surgery (p < 0.05) (Figure 1a). The expression levels of HO-1 mRNA in the liver of the BDL group decreased significantly compared with the sham group 1 h after surgery (p < 0.05) (Figure 1a). The expression levels of HO-1 mRNA in the liver of the BTED group increased significantly compared with the sham group 6 h after surgery (p < 0.05) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

The expression levels of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) mRNA in the liver. a 1 h after operation; b 6 h after operation. Results are presented as mean ± SE of mean (n = 12). *p < 0.05, compared with the sham group. BTED biliary tract external drainage, BDL bile duct ligation.

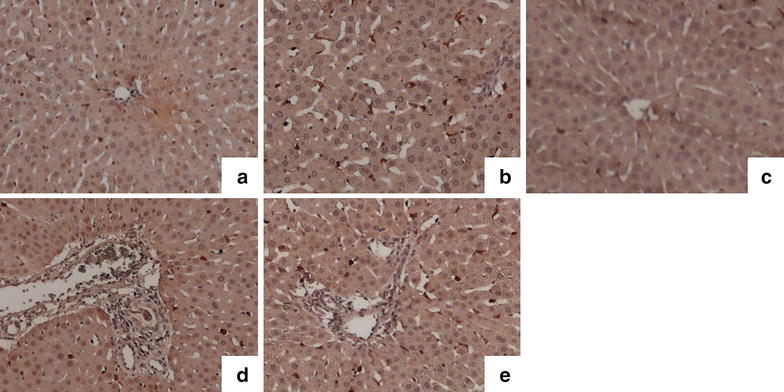

Immunohistochemistry

The expression levels of HO-1 in the liver of the BTED group increased significantly compared with the sham group 1 h after surgery (Figure 2a, b). The expression levels of HO-1 in the liver of the BDL group decreased significantly compared with the sham group 1 h after surgery (Figure 2a, c). The expression levels of HO-1 in the liver of the BTED group increased significantly compared with the sham group 6 h after surgery (Figures 2d, e).

Figure 2.

The expression levels of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in the liver. a Sham 1 h group; b BTED 1 h group; c BDL 1 h group; d sham 6 h group; e BTED 6 h group. The expression levels of HO-1 in the liver increased significantly after BTED at 1 and 6 h after surgery. The expression levels of HO-1 in the liver decreased significantly after BDL at 1 h after surgery. BTED biliary tract external drainage, BDL bile duct ligation.

Discussion

HO-1, a 32-kDa microsomal enzyme [3], catalyzes the rate-limiting step in oxidative degradation of heme to CO, biliverdin (soon reduced to bilirubin) and iron [4]. Since its discovery [5], studies have shown that HO-1 plays an important role in many modern medical disciplines, such as critical care [6–8], pulmonology [9–11], nephrology [12–14], gastroenterology [15–17], cardiology [18–20], neurology [21–23] and transplant immunology [24–26]. Sofalcone increases HO-1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells and blocks endothelial dysfunction [27]. The polymorphism of the guanidinium thiocyanate repeats in the HO-1 promoter region is associated with the development of necrotizing acute pancreatitis [28]. Capsaicin induces HO-1 expression in kidney tissues and ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal dysfunction. Notably, the protective effects of capsaicin were completely abrogated by treatment with HO-1 inhibitor [29]. HO-1 expression protects the heart from acute injury [30].

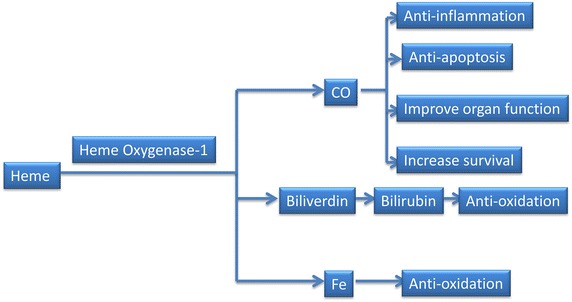

The HO-1 system plays a vital role in anti-oxidative stress, anti-inflammation and regulation of cytokine expression. The analysis of the HO-1 gene knockout mice showed that HO-1 is an important molecule in systemic responses to stress. Endothelial cells are more susceptible to cytotoxicity induced by pro-oxidant stimuli in this case and produce more intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) when challenged with such stimuli [31–33]. HO-dependent protection is due to the reaction products of HO activity. CO, biliverdin and iron each contribute to the restoration of cellular homeostasis under inducing conditions [34, 35]. CO decreases proinflammatory cytokine production [36–39], reduces apoptosis [40–42], improves organ function [43, 44] and increases survival [45–47]. Biliverdin and bilirubin, the end bile pigments of heme degradation, protect cells against injury caused by oxidative stress in vitro [46, 48, 49]. Iron potentially acts as a catalyst of deleterious pro-oxidant reactions [50–52] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The three end-products of heme oxygenase-1 activity can protect cells against injury.

Bilirubin may play a role via negative feedback on the formation of HO-1 according to theory. We speculate that BTED may induce compensatory increases in HO-1 expression in the liver by blocking the enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin. In this research, we found that the expression levels of HO-1 in the liver of the BTED group increased significantly compared with the sham group. The expression levels of HO-1 in the liver of the BDL group decreased significantly compared with the sham group. These results demonstrate that BTED may play important roles in anti-inflammation, anti-oxidative stress and regulation of cytokine expression by increasing the expression levels of HO-1. Specific roles of BTED in the treatment of diseases require further study.

Conclusion

The expression levels of HO-1 mRNA and protein in the liver increased significantly from 1 h after BTED and this effect lasts for more than 6 h. The expression levels of HO-1 mRNA and protein in the liver decreased significantly 1 h after BDL.

Authors’ contributions

LW, EZC and EQM drafted the manuscript. LW, BZ, and YC participated in the surgical procedure. LW and BZ carried out the immunohistochemistry. LM carried out the real-time PCR. LW and YC performed the statistical analysis. EZC and EQM conceived of the study, and participated in the design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81171789). We thank the staff of Shanghai Institute of Traumatology and Orthopaedics for their technical support.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Lu Wang, Email: saibeiyin@163.com.

Bing Zhao, Email: zhaobing124@163.com.

Ying Chen, Email: bichatlion@163.com.

Li Ma, Email: malipostgraduate2@163.com.

Er-Zhen Chen, Email: chenerzhen@hotmail.com.

En-Qiang Mao, Email: maoeq@yeah.net.

References

- 1.Janssen A, Fiebiger S, Bros H, Hertwig L, Romero-Suarez S, Hamann I, et al. Treatment of chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with epigallocatechin-3-gallate and glatiramer acetate alters expression of heme-oxygenase-1. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surolia R, Karki S, Kim H, Yu Z, Kulkarni T, Mirov SB, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 mediated autophagy protects against pulmonary endothelial cell death and development of emphysema in cadmium treated mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00097.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verma A, Hirsch DJ, Glatt CE, Ronnett GV, Snyder SH. Carbon monoxide: a putative neural messenger. Science. 1993;259:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.7678352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christodoulides N, Durante W, Kroll MH, Schafer AI. Vascular smooth muscle cell heme oxygenases generate guanylyl cyclase-stimulatory carbon monoxide. Circulation. 1995;91:2306–2309. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.91.9.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. The enzymatic conversion of heme to bilirubin by microsomal heme oxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;61:748–755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoetzel A, Leitz D, Schmidt R, Tritschler E, Bauer I, Loop T, et al. Mechanism of hepatic heme oxygenase-1 induction by isoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:101–109. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YH, Yoon DW, Kim JH, Lee JH, Lim CH. Effect of remote ischemic post-conditioning on systemic inflammatory response and survival rate in lipopolysaccharide-induced systemic inflammation model. J Inflamm (Lond) 2014;11:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao B, Fei J, Chen Y, Ying YL, Ma L, Song XQ, et al. Vitamin C treatment attenuates hemorrhagic shock related multi-organ injuries through the induction of heme oxygenase-1. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:442. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raval CM, Lee PJ. Heme oxygenase-1 in lung disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:1532–1540. doi: 10.2174/1389450111009011532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joo Choi R, Cheng MS, Shik Kim Y. Desoxyrhapontigenin up-regulates Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 expression in macrophages and inflammatory lung injury. Redox Biol. 2014;2:504–512. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shu YS, Tao W, Miao QB, Zhu YB, Yang YF. Improvement of ventilation-induced lung injury in a rodent model by inhibition of inhibitory kappaB kinase. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1417–1424. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin DH, Park HM, Jung KA, Choi HG, Kim JA, Kim DD, et al. The NRF2-heme oxygenase-1 system modulates cyclosporin A-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and renal fibrosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1051–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung S, Yoon HE, Kim SJ, Koh ES, Hong YA, Park CW, et al. Oleanolic acid attenuates renal fibrosis in mice with unilateral ureteral obstruction via facilitating nuclear translocation of Nrf2. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2014;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chintagari NR, Nguyen J, Belcher JD, Vercellotti GM, Alayash AI. Haptoglobin attenuates hemoglobin-induced heme oxygenase-1 in renal proximal tubule cells and kidneys of a mouse model of sickle cell disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2015;54:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoda Y, Amagase K, Kato S, Tokioka S, Murano M, Kakimoto K, et al. Prevention by lansoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, of indomethacin -induced small intestinal ulceration in rats through induction of heme oxygenase-1. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;61:287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takano T, Yonemitsu Y, Saito S, Itoh H, Onohara T, Fukuda A, et al. A somatostatin analogue, octreotide, ameliorates intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury through the early induction of heme oxygenase-1. J Surg Res. 2012;175:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu X, de Graaf IA, van der Bij HA, Groothuis GM. Precision cut intestinal slices are an appropriate ex vivo model to study NSAID-induced intestinal toxicity in rats. Toxicol In Vitro. 2014;28:1296–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motawi TK, Darwish HA. Abd El Tawab AM. Effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on endotoxin-induced cardiac stress in rats: a possible mechanism of protection. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2011;25:84–94. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YM, Cheng PY, Chim LS, Kung CW, Ka SM, Chung MT, et al. Baicalein, an active component of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, improves cardiac contractile function in endotoxaemic rats via induction of heme oxygenase-1 and suppression of inflammatory responses. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Issan Y, Kornowski R, Aravot D, Shainberg A, Laniado-Schwartzman M, Sodhi K, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 induction improves cardiac function following myocardial ischemia by reducing oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogawa T, Hanggi D, Steiger HJ. Treatment of experimental cerebral vasospasm by protein transduction of heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) conjugated to a residue of 11 arginines. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;112:111–113. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0661-7_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashabi G, Khalaj L, Khodagholi F, Goudarzvand M, Sarkaki A. Pre-treatment with metformin activates Nrf2 antioxidant pathways and inhibits inflammatory responses through induction of AMPK after transient global cerebral ischemia. Metab Brain Dis. 2014;30:747–754. doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9632-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trovato Salinaro A, Cornelius C, Koverech G, Koverech A, Scuto M, Lodato F, et al. Cellular stress response, redox status, and vitagenes in glaucoma: a systemic oxidant disorder linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:129. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchholz BM, Masutani K, Kawamura T, Peng X, Toyoda Y, Billiar TR, et al. Hydrogen-enriched preservation protects the isogeneic intestinal graft and amends recipient gastric function during transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;92:985–992. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318230159d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salahudeen AK, Yang M, Huang H, Dore S, Stec DE. Fenoldopam preconditioning: role of heme oxygenase-1 in protecting human tubular cells and rodent kidneys against cold-hypoxic injury. Transplantation. 2011;91:176–182. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181fffff2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noda K, Shigemura N, Tanaka Y, Bhama J, D’Cunha J, Kobayashi H, et al. Hydrogen preconditioning during ex vivo lung perfusion improves the quality of lung grafts in rats. Transplantation. 2014;98:499–506. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onda K, Tong S, Nakahara A, Kondo M, Monchusho H, Hirano T, et al. Sofalcone upregulates the nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2/heme oxygenase-1 pathway, reduces soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1, and quenches endothelial dysfunction: potential therapeutic for preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2015;65:855–862. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gulla A, Evans BJ, Navenot JM, Pundzius J, Barauskas G, Gulbinas A, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter polymorphism is associated with the development of necrotizing acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2014;43:1271–1276. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung SH, Kim HJ, Oh GS, Shen A, Lee S, Choe SK, et al. Capsaicin ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal injury through induction of heme oxygenase-1. Mol Cells. 2014;37:234–240. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hull TD, Bolisetty S, DeAlmeida AC, Litovsky SH, Prabhu SD, Agarwal A, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 expression protects the heart from acute injury caused by inducible Cre recombinase. Lab Invest. 2013;93:868–879. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poss KD, Tonegawa S. Reduced stress defense in heme oxygenase 1-deficient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10925–10930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsen R, Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Tokaji L, Bozza FA, Japiassu AM et al (2010) A central role for free heme in the pathogenesis of severe sepsis. Sci Transl Med 2:51ra71 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Kovtunovych G, Ghosh MC, Ollivierre W, Weitzel RP, Eckhaus MA, Tisdale JF, et al. Wild-type macrophages reverse disease in heme oxygenase 1-deficient mice. Blood. 2014;124:1522–1530. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryter SW, Alam J, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: from basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:583–650. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryter SW, Morse D, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide and bilirubin: potential therapies for pulmonary/vascular injury and disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:175–182. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0333TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakao A, Kimizuka K, Stolz DB, Seda Neto J, Kaizu T, Choi AM, et al. Protective effect of carbon monoxide inhalation for cold-preserved small intestinal grafts. Surgery. 2003;134:285–292. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohmoto J, Nakao A, Kaizu T, Tsung A, Ikeda A, Tomiyama K, et al. Low-dose carbon monoxide inhalation prevents ischemia/reperfusion injury of transplanted rat lung grafts. Surgery. 2006;140:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakhautdin B, Das D, Mandal P, Roychowdhury S, Danner J, Bush K, et al. Protective role of HO-1 and carbon monoxide in ethanol-induced hepatocyte cell death and liver injury in mice. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi EK, Park HJ, Sul OJ, Rajesekaran M, Yu R, Choi HS, et al. Carbon monoxide reverses adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance upon loss of ovarian function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308:621–630. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00458.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaizu T, Nakao A, Tsung A, Toyokawa H, Sahai R, Geller DA, et al. Carbon monoxide inhalation ameliorates cold ischemia/reperfusion injury after rat liver transplantation. Surgery. 2005;138:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schallner N, Fuchs M, Schwer CI, Loop T, Buerkle H, Lagreze WA, et al. Postconditioning with inhaled carbon monoxide counteracts apoptosis and neuroinflammation in the ischemic rat retina. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikolic I, Saksida T, Mangano K, Vujicic M, Stojanovic I, Nicoletti F, et al. Pharmacological application of carbon monoxide ameliorates islet-directed autoimmunity in mice via anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects. Diabetologia. 2014;57:980–990. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazzola S, Forni M, Albertini M, Bacci ML, Zannoni A, Gentilini F, et al. Carbon monoxide pretreatment prevents respiratory derangement and ameliorates hyperacute endotoxic shock in pigs. FASEB J. 2005;19:2045–2047. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3782fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao L, Wang P, Chen M, Liu Y, Zhou L, Fang X, et al. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecules attenuate postresuscitation myocardial injury and protect cardiac mitochondrial function by reducing the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in a rat model of cardiac arrest. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;20:330–341. doi: 10.1177/1074248414559837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otterbein LE, Otterbein SL, Ifedigbo E, Liu F, Morse DE, Fearns C, et al. MKK3 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mediates carbon monoxide-induced protection against oxidant-induced lung injury. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2555–2563. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63610-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nuhn P, Mitkus T, Ceyhan GO, Kunzli BM, Bergmann F, Fischer L, et al. Heme oxygenase 1-generated carbon monoxide and biliverdin attenuate the course of experimental necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2013;42:265–271. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318264cc8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Qin W, Qiu X, Cao J, Liu D, Sun B. A novel role of exogenous carbon monoxide on protecting cardiac function and improving survival against sepsis via mitochondrial energetic metabolism pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10:777–788. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foresti R, Green CJ, Motterlini R. Generation of bile pigments by haem oxygenase: a refined cellular strategy in response to stressful insults. Biochem Soc Symp. 2004;71:177–192. doi: 10.1042/bss0710177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ben-Amotz R, Bonagura J, Velayutham M, Hamlin R, Burns P, Adin C. Intraperitoneal bilirubin administration decreases infarct area in a rat coronary ischemia/reperfusion model. Front Physiol. 2014;5:53. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kvam E, Hejmadi V, Ryter S, Pourzand C, Tyrrell RM. Heme oxygenase activity causes transient hypersensitivity to oxidative ultraviolet A radiation that depends on release of iron from heme. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1191–1196. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hurttila H, Koponen JK, Kansanen E, Jyrkkanen HK, Kivela A, Kylatie R, et al. Oxidative stress-inducible lentiviral vectors for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1271–1279. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yegin ZA, Iyidir OT, Demirtas C, Suyani E, Yetkin I, Pasaoglu H, et al. The interplay among iron metabolism, endothelium and inflammatory cascade in dysmetabolic disorders. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;38:333–338. doi: 10.1007/s40618-014-0174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]