Abstract

Stress-related (e.g., depression) and metabolic pathologies (e.g., obesity) are important and often co-morbid public health concerns. Here we identify a connection between peripheral glucocorticoid receptor (GR) signaling originating in fat with the brain control of both stress and metabolism. Mice with reduced adipocyte GR hypersecrete glucocorticoids following acute psychogenic stress and are resistant to diet-induced obesity. This hypersecretion gives rise to deficits in responsiveness to exogenous glucocorticoids, consistent with reduced negative feedback via adipocytes. Increased stress reactivity occurs in the context of elevated hypothalamic expression of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis-excitatory neuropeptides and in the absence of altered adrenal sensitivity, consistent with a central cite of action. Our results identify a novel mechanism whereby activation of the adipocyte GR promotes peripheral energy storage while inhibiting the HPA axis, and provide functional evidence for a fat-to-brain regulatory feedback network that serves to regulate not just homeostatic energy balance but also responses to psychogenic stimuli.

Keywords: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, corticosterone, adipose, obesity, stress

1. Introduction

Stressors mobilize energy reserves to ensure survival under energetically-demanding conditions of real or perceived adversity (de Kloet et al., 2005; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). As would then be expected, there is an intricate relationship between the systems that regulate metabolism and the systems that are stimulated in response to stress. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a primary component of the metabolic stress response, culminating in the secretion of glucocorticoids (corticosterone in mice; cortisol in humans) and consequent redistribution of fuel sources (mobilization of hepatic glucose production, enhanced adipocyte differentiation). The interrelated contribution of the HPA axis to stress and metabolism is reflected in the link between excess glucocorticoids and visceral adiposity (e.g., Cushing’s disease) (Masuzaki et al., 2001; Pasquali et al., 2006), and by evidence for pathological HPA axis activity in psychiatric pathologies such as depression (Holsboer, 2000) as well as in metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity (Masuzaki et al., 2001; Pasquali et al., 2006; Rosmond et al., 1998). Furthermore, obesity predisposes individuals to develop depression (Roberts et al., 2003; Simon et al., 2006).

Stress activation of the HPA axis is controlled by negative feedback mechanisms, whereby glucocorticoids bind to cognate receptors to inhibit further release of ACTH. There are two known receptors for glucocorticoids, the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR). The MR has high affinity for glucocorticoids and is extensively bound under resting conditions, even at the nadir of the circadian rhythm (De Kloet et al., 1998). In contrast, the GR is only extensively occupied at high circulating glucocorticoid levels, and is the major mediator of negative feedback (Myers et al., 2012). In recent years it has become apparent that feedback can be mediated by multiple mechanisms. For example, fast feedback shut-off of CRH neurons is mediated by non-genomic, membrane glucocorticoid signaling, probably mediated by the GR (Evanson et al., 2010). Additional regions are also involved in feedback inhibition, including the hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex and even nucleus of the solitary tract neurons in the hindbrain (Ghosal et al., 2014; McKlveen et al., 2013; Myers et al., 2012). Consequently, regulation of stress responses is a distributed process involving multiple brain mechanisms.

Although the inter-relationship between stress-responding and metabolism is documented, the underlying mechanism(s) connecting the systems that regulate energy storage and those that regulate the HPA axis are not clear. There is extensive overlap between the brain mechanisms regulating stress responses and those that influence metabolism and this is likely further complicated by peripheral factors. In this regard, it has been hypothesized that a factor within adipose tissue plays an important role in mediating the interactions by coordinately regulating energy storage and HPA-axis stress responsiveness (Dallman et al., 2003b; Laugero et al., 2001). Consistent with this hypothesis, the ingestion of comfort foods during stress exposure suppresses HPA axis activity by stimulating reward circuitry in the brain (Ulrich-Lai et al., 2010), while the redistribution of adiposity towards increased visceral stores contributes to the attenuation of HPA responding (Dallman et al., 2003b; Laugero et al., 2001; Pecoraro et al., 2004).

While it is accepted that glucocorticoids inhibit their own secretion via the activation of GR within specific brain regions and in the pituitary, the existence of peripheral populations of GR in tissues such as white adipose tissue raises the possibility of reciprocal body-to-brain feedback signals that link metabolic and neural processing in the regulation of key stress responses. The present studies are based on the realization that GR is highly expressed in adipocytes and therefore is an ideal position to mediate the interactions between stress and metabolism. To assess this possibility, we investigated the role of adipocyte glucocorticoid signaling in energy metabolism and HPA axis activity using mice with selective knockdown of the GR in fat cells. We demonstrate that direct action of glucocorticoids on GR within adipocytes is an important mechanism for both HPA axis and metabolic regulation. This pathway may represent an important link between obesity and psychopathology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Mice containing the GR flox allele (Brewer et al., 2003) were crossed with mice containing Cre recombinase under control of the adiponectin promoter (Wang et al., 2010) to generate mice (C57BL/6 × 129 background) with reduced GR in adipocytes. Adult male and female adipocyte-GR knock-down mice (KO) and littermate controls expressing only the adiponectin Cre transgene (and for an additional control experiment containing only the GRflox allele [i.e., no adiponectin Cre transgene]) were housed one per cage on a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle. Mice were 8–10 wks old at the initiation of studies and were fed either standard rodent chow (Harlan Teklad LM-485; 3.1 kcal/g; ~5% fat) or high-fat diet (HFD; Research Diets D03082706; 4.54 kcal/g; ~40% fat). Unless otherwise noted, food and water were available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. HPA axis

Tail blood samples were collected during the circadian nadir and circadian peak of CORT secretion. For acute stress, mice were placed in plastic restrainers for 30 min, and tail blood samples were collected at 0, 30, 60 and 120 min after onset of restraint. For the dexamethasone-restraint challenge, mice were given dexamethasone (0.1 mg/kg sc) or saline and 2 h later were placed in restrainers, with blood sampled as above. In order to determine adrenal responsivity to exogenous ACTH, mice were first given a high dose of dexamethasone (4 ug/kg sc), which was pre-determined to prevent endogenous CORT production in both KO and CON mice. 2 h following dexamethasone administration, mice were given a low 0.01 mg/kg dose of ACTH in a 0.5 % BSA in 0.1 M PBS vehicle. This dose was pre-determined to cause a CORT response that is equivalent to 50% of the maximal response. 15 min later tail blood samples were collected into EDTA-coated tubes for the assessment of plasma CORT levels.

2.3 Analysis of plasma hormones

Blood samples collected from tail-bleeds as well as from terminal experiments were kept on ice until centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 15 min and plasma collection. Plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until assessment of plasma hormone levels. Blood glucose was determined using a Freedom Lite glucose meter. Plasma CORT and ACTH were assessed by RIA (Krause et al., 2011). Plasma insulin (during ad libitum feeding conditions and subsequent to a 16-h fast) and plasma leptin (during ad libitum feeding conditions, subsequent to a 16-h fast and during a 30 min restraint challenge) were assessed using ELISA kits from Crystal Chem, Inc. The detection limits of these kits are 0.1 ng/ml and 0.2 ng/ml, for insulin and leptin respectively. Plasma adiponectin was assessed by the mouse metabolic phenotyping center at the University of Cincinnati using an ELISA kit from Millipore, Inc. (Cat. #EZRADP-62K).

2.4. Body mass and food intake

Mice were given low-fat chow until 105 days of age. Between Day 105 and Day 147, mice were fed a HFD. During this time, body weight and food intake were assessed every 3–4 days at the same time of day (2–4 h after lights on).

2.5. Body composition and fat pad weights

Body composition was determined using NMR technology (Echo NMR, Waco, TX) on unanesthetized mice as previously described (Taicher et al., 2003). At the time of sacrifice (Day 147), distribution of adipose tissue in the epidydimal (eWAT), mesenteric (mWAT), retroperitoneal (rpWAT) and inguinal (iWAT) depots was determined by carefully removing and weighing the individual fat pads.

2.6. Adipocyte separation

The adipocyte and stromal vascular fractions of epidydmal white adipose tissue (eWAT; ~400 mg) were separated by collagenase digestion (200 U/ml; 60 min at 37° C under constant agitation), filtration and centrifugation. Floating adipocytes and pelleted stromal vascular cells were collected and RNA extracted.

2.7. Adipocyte morphometry

Determination of mean adipocyte size and distribution of adipocyte size was modified from previous studies (Kim et al., 2008). Images of adipocytes were captured by a light microscope (Carl Zeiss, USA). The cross-sectional area of adipocytes was measured on paraffin-embedded hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of epididymal fat at a magnification of 200 × by image processing with customized software written in Labview 9.0 edition (National Instruments, TX, USA). In total, 800 to 1500 adipocytes in each mouse were assessed. The color images were converted to binary images by adjusting the threshold. The contour of adipocytes was made clear with ’paintbrush’ function if the adipocytes were not clearly discriminated because obscure or broken outlines. The distribution of adipocyte size was determined by relative frequencies of adipocytes having a specific size within a set interval (250 μm2). The mean adipocyte size for each mouse was determined by averaging the cross-sectional area of all assessed adipocytes and the mean adipocyte sizes between CON and KO mice were compared. Subsequently, the adjusted adipocyte number of each mouse was determined by dividing weight of epididymal fat by the mean adipocyte size and the adjusted adipocyte size was compared between the groups.

2.8. RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and Real-time PCR

Gene expression studies were conducted on tissue samples collected from male CON and KO mice maintained on a standard diet. RNAeasy columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were used to isolate RNA from tissue samples (de Kloet et al., 2011). DNAase treatment (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was performed to minimize genomic DNA contamination of RNA extracts. For hypothalamic gene expression analysis, the hypothalamus was dissected from the frozen brains and submerged in 700 μl of RLT buffer from the Qiagen RNAeasy kit on the day of RNA extraction. For the hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenals, RNA extraction and DNAase treatment procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A slightly modified protocol was used for RNA extraction from WAT, adipocytes and the stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue. A small sample (<100 mg) of frozen adipose tissue or the separated fraction of adipose tissue (i.e., the SVF or AC fraction) was submerged in 1 ml TriReagent (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX) and homogenized. Bromo-3-chloro-propane (200 μl) was then added and the samples were centrifuged (10,000 rpm) for 10 min. Ethanol (70 %, 500 μl) was added to the supernatant, the mixture was applied to the RNeasy columns, and RNA extraction and DNAase treatment were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. iScript (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to synthesize cDNA from 0.1–1 μg total RNA, depending on the tissue. Duplicate cDNA samples were run using a 7900HT Fast Real-time PCR system, Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix and validated Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Gene expression was normalized to L32 and quantified using the 2ΔΔCt method (de Kloet et al., 2011).

2.9. Western Blot

Western blot analysis of GR levels was performed as previously described (Murphy et al., 2002) using ~50 ug protein and a primary antibody obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA,GR M-20).

2.10. Statistics

Data are reported as mean ± SEM. For comparisons of two groups, data were analyzed using student’s t-tests. For comparisons of multiple groups, data were analyzed using one-way or two-way ANOVA, with repeated-measures (for endpoints assessed at multiple time-points). When appropriate, Bonferroni post hoc analyses were performed. In all cases, significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

3. Results

3.1. Specific Cre/lox-mediated deletion of the glucocorticoid receptor from adipocytes

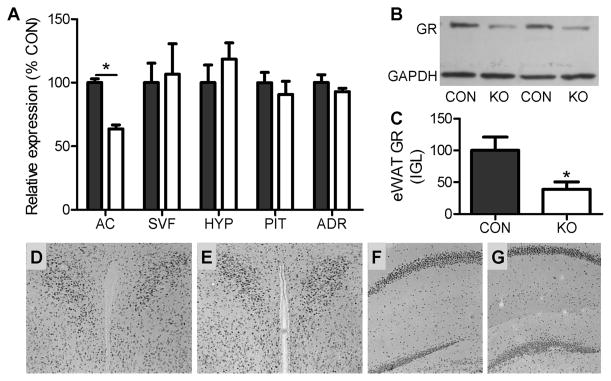

For these studies, Cre-recombinase was expressed under the control of the promoter for adiponectin, a molecule expressed exclusively in adipocytes (Hu et al., 1996; Scherer et al., 1995). Expression of this adiponectin-Cre transgene (Wang et al., 2010) in knock-in mice homozygous for a loxP-flanked GR exon 2 (Brewer et al., 2003) leads to a significant reduction in GR protein in eWAT [t(8) = 3.23, p < 0.05], with no off-target reduction in GR expression within the hypothalamus, pituitary, adrenal glands or specific brain nuclei (Fig. 1). Within eWAT, the reduction in GR mRNA is limited to the adipocytes (n = 6/group; t(10) = 8.98, p < 0.001), as there is no reduction in GR expression in the stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue (n = 6/group; t(10) = 0.26; Fig. 1). Furthermore, based on evidence that GR expression is greater in visceral than subcutaneous adipose tissue depots we hypothesized that the extent of GR deletion would be the greatest within the visceral WAT depots. In order to determine if this was indeed the case, the level of GR expression was assessed in whole adipose tissue samples collected from KO and CON samples of eWAT, iWAT, rpWAT and mWAT. Their relative expressions were as follows: [iWAT: 100 ± 6.17 vs. 67.3 ± 5.43; t(20) = 3.76; p < 0.001], [rpWAT: 100 ± 9.27 vs. 70.1 ± 6.36; t(21) = 2.36; p < 0.05], [eWAT: 100 ± 7.1 vs. 80.8 ± 7.03; t(19) = 1.81; p = 0.09], and [mWAT: 100 ± 9.37 vs. 100.2 ± 10.92; t(20) = 0.013; p = 0.98]. That is, the more viscerally localized depots had an apparent lower level of GR knockdown. That being said, visceral adipose tissue is also more highly vascularized than the more subcutaneously situated depots. Since the SVF of adipose tissue also contains GR, it is possible that the deletion of GR from adipocytes is masked by the high intact GR expression in the SVF compartment, and that this is more apparent in visceral depots.

Fig. 1. Co-expression of the GR flox knock-in gene and the adiponectin-cre transgene leads to selective down-regulation of adipocyte GR.

(A) Real-time PCR assessment of GR expression in adipocytes (AC; n = 4–6/group), the stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue (SVF; n = 4–6/group), the hypothalamus (HYP; n = 7–9/group), the pituitary (PIT; n = 7–9/group) and the adrenal (ADR; n = 7–9/group) in mice expressing both adiponectin-cre and GR flox (KO) and control littermates expressing the adiponectin-cre transgene in the context of a wild-type GR (CON). (B-C) Western blot analysis of GR expression within epidydimal white adipose tissue (eWAT) of two representative KO and CON samples verifying loss of GR protein in the KO. n = 4–6/group. (D-G) Immunohistochemistry for GR in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) of CON (D) and KO (E) and hippocampus of CON (F) and KO (G), showing sparing of central GR in KO mice. * = p < 0.05. t-tests [two-tailed] were used for the analysis of these data. Bars represent 1 SEM.

3.2. Adipocyte glucocorticoid receptors negatively regulate activation of the HPA axis

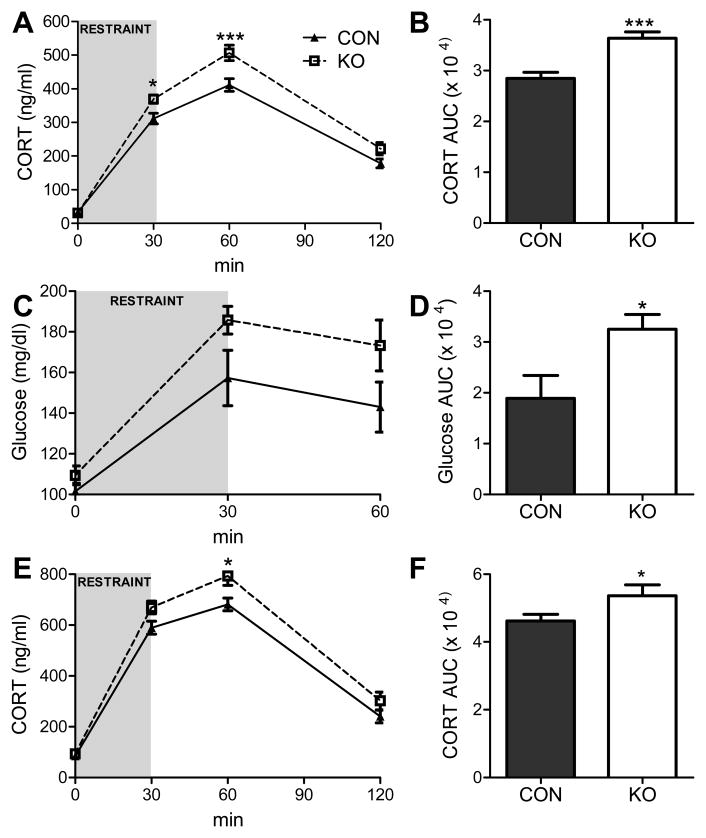

To directly test the hypothesis that the adipocyte GR plays an important role in regulation of the HPA axis, the glucocorticoid response to an acute 30-min restraint challenge, a psychogenic stressor, was assessed. Adipocyte GR-knockdown mice and controls had similar non-stressed levels of corticosterone (CORT; the active glucocorticoid in mice) during both the circadian nadir (1–2 h after lights on; 37.0 ± 9.3 vs. 33.4 ± 13.6 ng/ml) and the circadian peak (1–2 h prior to lights off; 146.7 ± 27.4 vs. 132.7 ±14.8 ng/ml) of CORT secretion. Similarly, the basal non-stressed glucose levels were also comparable between the groups (101.5 ± 3.94 vs.109.3 ± 4.60 ng/ml). When challenged with the acute 30-min restraint stress, male mice lacking GR in adipocytes had augmented CORT and hyperglycemic responses (Fig. 2). That is, although basal CORT and glucose levels were not affected by deletion of GR in adipocytes, stress-induced elevations in plasma CORT [interaction: F(3, 201) = 6.30, p < 0.001] and blood glucose [main effect of genotype: F(1,16) = 4.62, p < 0.05; main effect of time: F(2,32) = 37.94, p < 0.0001] were significantly augmented relative to controls. Bonferroni post hoc analysis of the CORT responses revealed that significant elevations in CORT occurred 30 and 60 min subsequent to the onset of restraint. Moreover, the integrated CORT [AUC: t(67) = 4.614, p < 0.01] and hyperglycemic responses [AUC: t(16) = 2.77, p < 0.05] to the stressor were similarly enhanced. Importantly, male adipocyte GR-knockdown mice have an enhanced CORT response to restraint relative to mice that express only the GR-flox gene, as well as to mice that express only the Cre transgene, obviating the possibility that either the GR-flox or the adiponectin-Cre genetic manipulation alone underlies the alterations in stress reactivity (Fig. S1). Furthermore, enhanced stress responsiveness and was observed in both male and female adipocyte-GR knockdown mice (interaction: F(3,123) = 2.89, p < 0.05; AUC: t(41) = 2.29, p < 0.05; Fig. 2) and was also observed in male mice maintained on a high-fat diet [interaction: F (3, 54) = 3.88, p < 0.01; AUC: t (18) = 3.78, p < 0.01; Fig. S2].

Fig. 2. Adipocyte GRs negatively regulate the corticosterone (CORT) response to restraint.

(A) CORT response to an acute 30-min restraint challenge and (B) the integrated AUC of the CORT response in male adipocyte GR knockdown (KO) vs. control (CON) mice expressing only the Cre transgene [n = 33–36/group]. (C) The glucose response to an acute 30-min restraint challenge and (D) the glucose AUC during the restraint challenge [n = 9/group]. (E) CORT response to 30-min restraint in female KO mice and in CON and (F) the AUC for the CORT response [n = 20–23/group]. * = p < 0.05; *** = p < 0.001. Data were analyzed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (A, C and E) or a t-test (two-tailed; B, D, and F). Bonferroni post hoc analyses were performed. Bars represent 1 SEM.

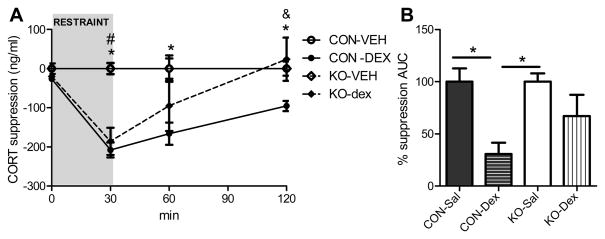

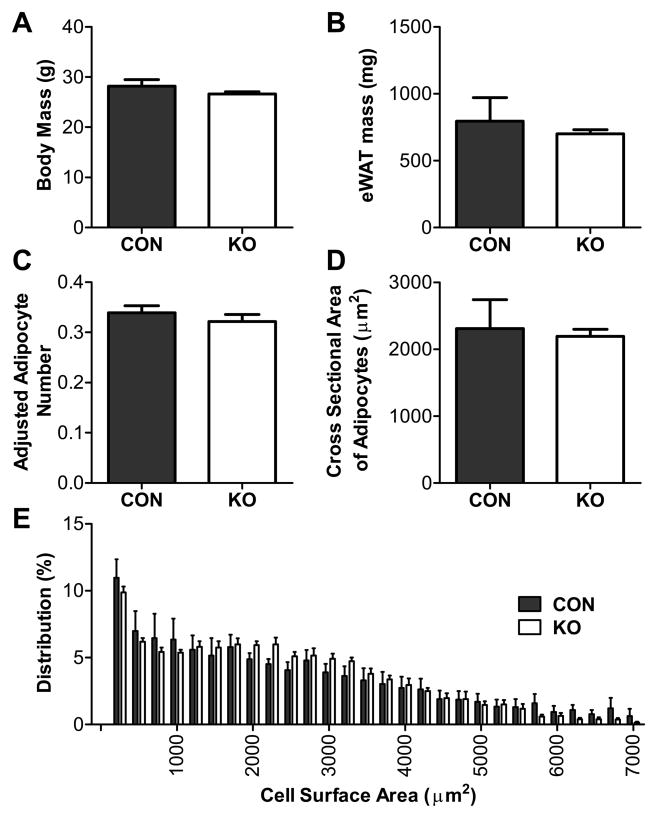

We subsequently assessed responses to glucocorticoid feedback by injecting a low-dose of dexamethasone prior to stress testing. Mice with reduced adipocyte GR had a more rapid escape from the inhibitory effect of the exogenous glucocorticoid on restraint-induced corticosterone release, consistent with impaired negative feedback of the HPA axis (interaction: F(9,45) = 4.51, p < 0.001; Fig. 3). Notably, although energy status itself has a multifaceted role in the regulation of stress-responding (Dallman et al., 2005; Flak et al., 2011; South et al., 2012), the enhanced HPA responsiveness in mice with selective adipocyte GR knockdown occurs in the absence of a metabolic phenotype in that body mass, adipose mass and adipose morphology are similar in knockdown and control mice when they are maintained on a standard diet (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. Modified dexamethasone suppression test.

Male adipocyte GR knockdown mice (KO) and control mice (CON) were given dexamethasone at a threshold dose (0.1 mg/kg) or saline vehicle 2 h prior to the onset of a restraint challenge and the ability of dexamethasone to suppress the CORT response to restraint was assessed. (A) CORT levels [* = CON-dexamethasone significantly different from CON-saline, p < 0.05; # = KO-dexamethasone significantly different from KO-saline, p < 0.05; & = KO-dexamethasone significantly different from CON-dexamethasone, p < 0.05; two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis] and (B) the integrated CORT AUC during the modified dexamethasone suppression test [* = p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis]. n = 5/group. Bars represent 1 SEM.

Fig. 4. Adipose morphometry during standard low-fat chow feeding.

(A) Body mass, (B) eWAT mass, (C) adjusted adipocyte number, (D) cross-sectional area of adipocytes, and (E) distribution of adipocyte size of 15 wk-old adipocyte GR knockdown (KO) and control (CON) mice fed a standard low-fat chow diet. There were no differences between control and KO mice on any parameter measured. Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed t-tests. n = 4 –6/group. Bars represent 1 SEM.

3.3. Deletion of adipocyte GR modulates CNS systems regulating activation of the HPA axis and metabolism

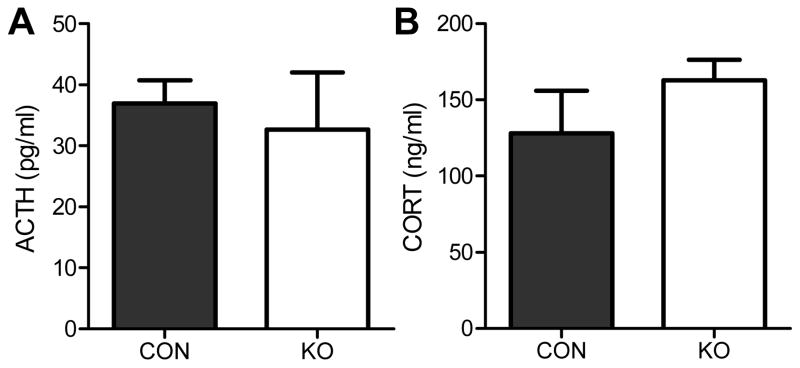

We next sought to determine the mechanism underlying the effects of adipocyte-GR knockdown on the HPA axis. Basal adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) secretion (1–2 h after lights on) was unaltered in mice lacking the adipose GR (Fig. 5). However, adipocyte GR-knockdown mice had similar adrenal responsivity to a fixed dose of ACTH, indicating that the enhanced CORT release is not due to enhanced adrenal sensitivity to ACTH (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Impact of adipocyte GR knockdown on ACTH levels and adrenal sensitivity to ACTH.

(A) Basal (non-stressed) levels of ACTH during the circadian nadir of the HPA axis. (B) Plasma CORT levels in CON and KO 15 min after an ip injection of ACTH (0.01 mg/kg). Adrenal sensitivity to ACTH did not differ between groups. Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed t-tests. n = 8–10/group. Bars represent 1 SEM.

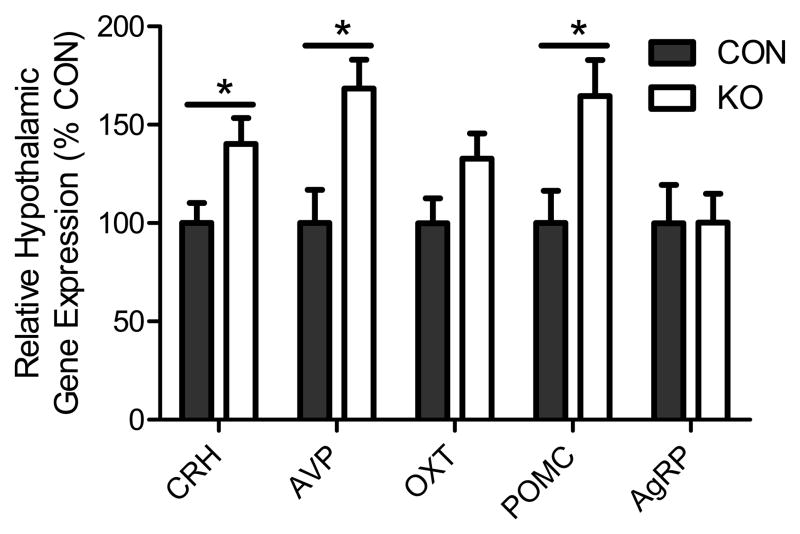

Drive of the HPA axis is mediated by PVN neurons via release of the ACTH secretagogues corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP). Analysis of hypothalamic gene expression revealed elevated levels of AVP [t(14) = 3.31, p < 0.01] and CRH [t(14) = 2.62, p < 0.05] mRNA in adipose GR knockdown mice, consistent with increased drive of this neuroendocrine system (similar to effects of adrenalectomy or chronic stress (Herman et al., 1995; Sawchenko, 1987); Fig. 6). These data suggest that adipose GR deficiency activates the central limb of the HPA axis.

Fig. 6. Impact of adipocyte GR knockdown on hypothalamic gene expression.

Non-stressed hypothalamic corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH), arginine vasopressin (AVP), oxytocin (OXT), proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) expression 2 h after the onset of the light-phase [* = p < 0.05]. Statistical analyses were performed via two-tailed t-tests. n = 7–9/group. Bars represent 1 SEM.

We then assessed the impact of adipose GR knockdown on peptidergic systems that transmit adipose signals to the central nervous system. In this regard, circulating baseline levels of adiposity factors (i.e., adiponectin, insulin and leptin) were not different between the groups during either ad libitum-feeding or fasting conditions (Fig. S3). Decreased adipocyte GR was, however, associated with increased hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin (the gene encoding α-MSH; Fig. 6; t(14) = 2.63, p < 0.05) gene expression, suggesting enhanced activity of this anorexigenic and stress-excitatory neuropeptidergic system.

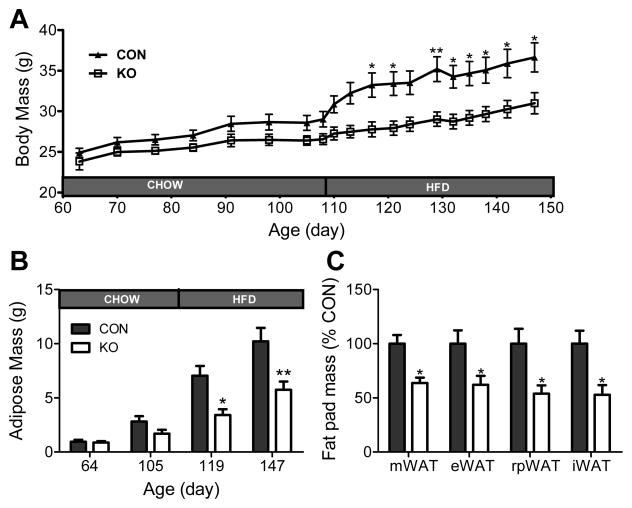

3.4. Adipocyte glucocorticoid receptors contribute to high-fat diet induced body mass and adiposity gain

When fed a standard low-fat diet, levels of body mass, adiposity and adipocyte morphology did not differ between mice with GR knockdown in adipocytes and controls (Fig. 4), nor did mean daily food intake (4.62 ± 0.37 g/day vs. 4.70 ± 0.27 g/day). However, mice with adipocyte GR knockdown gained less body weight (interaction: F(18, 342) = 6.91, p < 0.0001) and adipose mass (interaction: F(3,57) = 5.35, p < 0.01), and consumed less energy (3.65 ± 0.185 g/day vs. 2.99 ± 0.105 g/day; t(19) = 2.63, p < 0.05), relative to control mice when fed a diet high in fat (HFD, Fig. 7), indicating that the adipocyte GR is important in diet-induced weight gain. The reduction in adipose mass occurred in all adipose depots examined (Fig. 7; eWAT: t(19) = 2.59, p < 0.05; iWAT: t(19) = 3.18, p < 0.01; mWAT: t(19) = 3.19, p < 0.01; rpWAT: t(19) = 2.49, p < 0.05). These results highlight a gene-by-environment interaction wherein glucocorticoids enhance body fat accumulation only when the mice are subjected to obesigenic conditions.

Fig. 7. Reduced adipocyte GR expression attenuates diet-induced obesity.

KO and CON mice were fed a standard low-fat chow diet until 105 days of age. Then, between Day 105 – Day 147 (the termination of the study) mice were given a high-fat diet (HFD). (A) Body Mass, (B) Adipose Mass, and (C) Fat Pad Mass (expressed as a percentage of CON fat pad mass and assessed at the termination of the study). Data were analyzed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analyses. * = p < 0.05. ** = p < 0.01. n = 9 – 10/group. Bars represent 1 SEM.

4. Discussion

The HPA axis is regulated by a complexity of neuroendocrine and autonomic signals, and perturbations of HPA axis function contribute to a wide range of psychiatric and metabolic diseases (de Kloet et al., 2006; Holsboer, 2000; Pasquali et al., 2006; Rosmond et al., 1998). Previous studies document glucocorticoid regulation of HPA axis activity at the hypothalamic, pituitary and adrenal levels. However, it has been hypothesized that other populations of GR also regulate activity of the HPA axis (Dallman et al., 2003a; Dallman et al., 2003b). Collectively, our studies identify a novel pathway linking peripheral glucocorticoid signaling in adipocytes to the central regulation of both energy balance and neuroendocrine stress responses. We demonstrate that direct action of glucocorticoids on GR within adipocytes is an important mechanism for both HPA axis and metabolic regulation.

The exaggerated glucocorticoid response to a psychogenic stressor coupled with the impaired negative feedback of the HPA axis observed in mice with reduced GR in adipose tissue is reminiscent of what occurs during numerous stress-related conditions, such as major depression (Carroll, 1984; Vreeburg et al., 2009). Our results imply that activation of adipocyte GR may serve a protective role by temporally limiting glucocorticoid secretion after stressor exposure. Importantly, although energy status itself has a multifaceted role in the regulation of stress-responding (Dallman et al., 2005; Flak et al., 2011; South et al., 2012), the enhanced HPA responsiveness in mice with selective adipocyte GR knockdown occurs in the absence of a metabolic phenotype, in that body mass, adipose mass and adipose morphology are similar in knockdown and control mice. Thus, it is unlikely that the amount of adipose tissue per se is responsible for the enhanced HPA activity in mice with reduced adipocyte GR.

Our studies indicate that adipocyte GR knockdown permits escape from the inhibitory effect of dexamethasone, suggesting that fat is in an integrative site for feedback processing. Given that penetration of dexamethasone into the brain is limited (De Kloet et al., 1975), we attribute feedback effects to peripheral GR loss, which is only evident in adipocytes. However, it should also be noted that the reduced sensitivity to dexamethasone may be due, in part, to increased central drive at the level of the pituitary. Given the observed increase in hypothalamic CRH mRNA expression, it is possible elevated median eminence peptide release could account for at least part of the enhanced response seen with adipocyte GR knockdown following dexamethasone inhibition.

Importantly, subset of the present experiments was conducted in both males and females. The inclusion of both sexes in these initial experiments stemmed from the realization that males and females have known differences in adipose tissue distribution and HPA axis function (Goel et al., 2011). Females store relatively more adiposity in the subcutaneous depot, while males store more in the visceral depot (Woods et al., 2003). Furthermore adiponectin and GR are also differentially expressed in these depots, and it is possible that this model would have a distinct impact on females vs. males. However, because the results of the initial stress studies were comparable between males and females, the present study does not focus on potential sex differences (or lack thereof).

Despite the equivalent levels of adiposity between the adipocyte GR knockdown mice and controls maintained on a standard diet, the present data also reveal that adipocyte GR are important for the expansion of adipose tissue during high-fat diet feeding. Excess glucocorticoids are associated with increased visceral adiposity (e.g., Cushing’s disease) and previous studies have revealed that increasing active glucocorticoids specifically in adipose tissue renders mice more susceptible to obesity, whereas transgenic models that inactivate adipocyte glucocorticoids resist diet-induced obesity (Kershaw et al., 2005; Masuzaki et al., 2001; Pasquali et al., 2006). Our findings that mice lacking adipocyte GR are resistant to the development of diet-induced obesity further indicate that this population of GR is an important component of these processes.

The intricate relationship between the control of energy homeostasis and stress-responding is at least in part due to the overlap between the neural circuits that regulate these processes. Consistent with a central mechanism for the enhanced stress responsiveness, mice with reduced adipocyte GR had elevated levels of the hypothalamic ACTH secretagogues, corticotrophin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin. Upregulation of CRH and AVP is consistent with enhanced capacity for HPA activation (Herman et al, 1995), and suggests that loss of adipocyte GR has a lasting impact on central HPA axis drive.

Various adiposity factors (whose levels in circulation are dependent on the degree of adiposity) act on the brain both to regulate energy balance and also to influence stress responses. In this regard, the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC) is a key brain nucleus that senses, integrates and responds to these signals (Schwartz et al., 2000; Woods et al., 2000) to modulate both energy balance and HPA-axis function. Metabolic and HPA axis regulation occurs in part via ARC projections to the PVN (Swanson and Sawchenko, 1983), a nucleus responsible for the neuroendocrine and sympathetic nervous system regulation of many aspects of physiology. Within this neural circuit, AgRP acts to promote positive energy balance, while α-MSH reduces energy storage (Schwartz et al., 2000; Woods et al., 2000) and both of these factors influence HPA axis activity (Dhillo et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2003; Wahlestedt et al., 1987). Although the circulating baseline levels of adiposity factors (i.e., adiponectin, insulin and leptin) that modulate this circuit were not different between groups in the present study, decreased adipocyte GR was associated with increased hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin (the gene encoding α-MSH) expression, suggesting enhanced activity of this anorexigenic and stress-excitatory neuropeptidergic system. This result is consistent with a central mechanism for both the reduced susceptibility to diet-induced weight-gain and the enhanced HPA axis activity in mice lacking the adipocyte GR. In particular, in relation to weight gain, elevated POMC expression is suggestive of elevated α-MSH levels, which as mentioned above, reduces energy storage (Schwartz et al., 2000; Woods et al., 2000). It is therefore possible that this alteration in hypothalamic gene expression is contributing to the reduced propensity of adipocyte GR knockdown mice to become obese when given a HFD. Future studies may therefore examine this possibility by assessing the impact of interfering with this pathway on the metabolic phenotype observed.

It is also possible that the reduction in diet-induced obesity is related not only to a decrease in white adipocyte GR expression, but also to altered BAT GR expression. Although this possibility is not explored in the present studies, there is evidence in the literature to support this notion. There is some evidence that both adiponectin and GR are expressed in BAT, and therefore it is reasonable to hypothesize that the levels of GR within this tissue would be reduced in the present adipocyte GR knockdown mice (Iacobellis et al., 2013; Viengchareun et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2002). While dexamethasone reduces the proliferation of human white adipocytes, it stimulates proliferation of human brown adipocytes (Barclay et al., 2015). Furthermore, in BAT, 11β-HSD1, which amplifies local glucocorticoid activity within the tissue, has profound effects on BAT function (Liu et al., 2013). As a consequence, it is possible that both of WAT and BAT-centered mechanisms are at play when considering the metabolic phenotype observed in the present studies.

Another important consideration in the present studies is the specificity of the knockdown of the glucocorticoid receptor to adipocytes. Although there are several studies that have localized adiponectin exclusively to adipocytes (Hu et al., 1996; Scherer et al., 1995), some more recent studies have localized adiponectin to other tissues, such as the pituitary (Rodriguez-Pacheco et al., 2007). For this reason, we have assessed GR mRNA levels in several additional tissues known to be critical in initiating and modulating stress responses, including brain, pituitary and adrenal. Qualitatively, GR protein within specific brain regions appears to be expressed similarly between the groups and quantitatively, the mRNA levels of GR are similar within the brains, pituitaries, adrenals and the stromal vascular fractions of adipose tissue collected from CON and KO mice. We cannot, however, conclude that GR expression remains unaltered in all other tissues of adipocyte GR knockdown mice and therefore acknowledge that a deficit in some other unknown area may be contributing to some of the observed effects. Nonetheless, we can conclude from the present data that GR in adiponectin-containing cells, which are accepted to be predominately adipocytes, do impact metabolism and exert stress modulatory actions.

It is also evident from the literature that GR is differentially expressed in subcutaneous vs. visceral adipose tissue depots, with a greater abundance of GR being localized to visceral adipose tissue. This distribution of GR, coupled with the known impact of pathological glucocorticoid excess (e.g., Cushing’s disease) to preferentially lead to an increase in visceral adiposity, led us to hypothesize that adipocyte GR deletion would lead to more profound alterations in visceral vs. subcutaneous adiposity. However, this was not the case, as there was a comparable decrease in the susceptibility of all adipose depots examined to expand when subjected to HFD.

The mind-body relationship has largely been interpreted as the important role that the mind plays in diseases of the body. The literature is replete with examples indicating how mental state can impact disease processes (e.g., cardiovascular disease). However, the mind-body relationship clearly works in the opposite direction. Signals from peripheral organs can have substantial impact on CNS function including the susceptibility to a range of devastating physiological and psychological conditions. The current work identifies a critical role of adipose glucocorticoid signaling in regulation of HPA function, identifying a mechanism whereby the status of adipose tissue can have direct impact on CNS functions that link obesity and metabolic disease with stress-related pathologies. Moreover, control of higher cognitive function (stress reactivity) by adipose signaling may represent an important link between metabolic diseases (e.g., obesity) and mood disorders (e.g., depression, post-traumatic stress disorder) that may contribute to increasing incidence of these co-morbid pathologies.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Mice with reduced adipocyte GR hypersecrete glucocorticoids following acute stress

Adipocyte GR knockdown mice have impaired negative feedback of the HPA axis

Mice with reduced GR in adipocytes are resistant to diet-induced obesity

This study highlights a fat to brain regulatory mechanism controlling the HPA axis

Acknowledgments

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE

The present studies were funded by NIH grants, MH069860, MH049698, HL096830 and NS068122. The funding source had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

The authors would like to thank Drs. Scherer and Muglia for the donation of the Adiponectin Cre and GR flox mouse lines.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: A.D.dK., E.G.K., and M.B.S. designed and conducted all experiments, analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. J.N.F., K.A.S., D.H.K., B.M., Y.M.U. assisted in the data collection and the interpretation of the results. S.C.W., R.J.S. and J.P.H. oversaw the design and execution of the experiment, assisted in the interpretation of the results and prepared the manuscript for publication. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barclay JL, Agada H, Jang C, Ward M, Wetzig N, Ho KK. Effects of glucocorticoids on human brown adipocytes. J Endocrinol. 2015;224:139–147. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Khor B, Vogt SK, Muglia LM, Fujiwara H, Haegele KE, Sleckman BP, Muglia LJ. T-cell glucocorticoid receptor is required to suppress COX-2-mediated lethal immune activation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1318–1322. doi: 10.1038/nm895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll BJ. Dexamethasone suppression test for depression. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1984;39:179–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Akana SF, Laugero KD, Gomez F, Manalo S, Bell ME, Bhatnagar S. A spoonful of sugar: feedback signals of energy stores and corticosterone regulate responses to chronic stress. Physiol Behav. 2003a;79:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Pecoraro N, Akana SF, La Fleur SE, Gomez F, Houshyar H, Bell ME, Bhatnagar S, Laugero KD, Manalo S. Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of “comfort food”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003b;100:11696–11701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934666100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Pecoraro NC, la Fleur SE. Chronic stress and comfort foods: self-medication and abdominal obesity. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet AD, Krause EG, Scott KA, Foster MT, Herman JP, Sakai RR, Seeley RJ, Woods SC. Central angiotensin II has catabolic action at white and brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E1081–1091. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00307.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet CS, Vermetten E, Geuze E, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ, Westenberg HGM. Assessment of HPA-axis function in posttraumatic stress disorder: Pharmacological and non-pharmacological challenge tests, a review. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:550–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E, Oitzl MS, Joels M. Brain corticosteroid receptor balance in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:269–301. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet R, Wallach G, McEwen BS. Differences in corticosterone and dexamethasone binding to rat brain and pituitary. Endocrinology. 1975;96:598–609. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-3-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillo WS, Small CJ, Seal LJ, Kim MS, Stanley SA, Murphy KG, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. The hypothalamic melanocortin system stimulates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in vitro and in vivo in male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2002;75:209–216. doi: 10.1159/000054712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanson NK, Tasker JG, Hill MN, Hillard CJ, Herman JP. Fast feedback inhibition of the HPA axis by glucocorticoids is mediated by endocannabinoid signaling. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4811–4819. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flak JN, Jankord R, Solomon MB, Krause EG, Herman JP. Opposing effects of chronic stress and weight restriction on cardiovascular, neuroendocrine and metabolic function. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal S, Bundzikova-Osacka J, Dolgas CM, Myers B, Herman JP. Glucocorticoid receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) decrease endocrine and behavioral stress responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;45:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel N, Workman JL, Lee TT, Innala L, Viau V. Sex Differences in the HPA Axis. Compr Physiol. 2011;4:1121–1155. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Adams D, Prewitt C. Regulatory changes in neuroendocrine stress-integrative circuitry produced by a variable stress paradigm. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;61:180–190. doi: 10.1159/000126839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F. The Corticosteroid Receptor Hypothesis of Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:477–501. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu E, Liang P, Spiegelman BM. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10697–10703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobellis G, Di Gioia C, Petramala L, Chiappetta C, Serra V, Zinnamosca L, Marinelli C, Ciardi A, De Toma G, Letizia C. Brown fat expresses adiponectin in humans. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:126751. doi: 10.1155/2013/126751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw EE, Morton NM, Dhillon H, Ramage L, Seckl JR, Flier JS. Adipocyte-specific glucocorticoid inactivation protects against diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2005;54:1023–1031. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Sandoval D, Reed JA, Matter EK, Tolod EG, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. The role of GM-CSF in adipose tissue inflammation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1038–1046. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00061.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause EG, de Kloet AD, Scott KA, Flak JN, Jones K, Smeltzer MD, Ulrich-Lai YM, Woods SC, Wilson SP, Reagan LP, Herman JP, Sakai RR. Blood-borne angiotensin II acts in the brain to influence behavioral and endocrine responses to psychogenic stress. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15009–15015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0892-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugero KD, Bell ME, Bhatnagar S, Soriano L, Dallman MF. Sucrose ingestion normalizes central expression of corticotropin-releasing-factor messenger ribonucleic acid and energy balance in adrenalectomized rats: a glucocorticoid-metabolic-brain axis? Endocrinology. 2001;142:2796–2804. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Kong X, Wang L, Qi H, Di W, Zhang X, Wu L, Chen X, Yu J, Zha J, Lv S, Zhang A, Cheng P, Hu M, Li Y, Bi J, Hu F, Zhong Y, Xu Y, Ding G. Essential roles of 11beta-HSD1 in regulating brown adipocyte function. J Mol Endocrinol. 2013;50:103–113. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XY, Barsh GS, Akil H, Watson SJ. Interaction between alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and corticotropin-releasing hormone in the regulation of feeding and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal responses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7863–7872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07863.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuzaki H, Paterson J, Shinyama H, Morton NM, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR, Flier JS. A transgenic model of visceral obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Science. 2001;294:2166–2170. doi: 10.1126/science.1066285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKlveen JM, Myers B, Flak JN, Bundzikova J, Solomon MB, Seroogy KB, Herman JP. Role of prefrontal cortex glucocorticoid receptors in stress and emotion. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy EK, Spencer RL, Sipe KJ, Herman JP. Decrements in nuclear glucocorticoid receptor (GR) protein levels and DNA binding in aged rat hippocampus. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1362–1370. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers B, McKlveen JM, Herman JP. Neural Regulation of the Stress Response: The Many Faces of Feedback. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2012;32:683–694. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9801-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali R, Vicennati V, Cacciari M, Pagotto U. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1083:111–128. doi: 10.1196/annals.1367.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecoraro N, Reyes F, Gomez F, Bhargava A, Dallman MF. Chronic stress promotes palatable feeding, which reduces signs of stress: feedforward and feedback effects of chronic stress. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3754–3762. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Deleger S, Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective association between obesity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:514–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Pacheco F, Martinez-Fuentes AJ, Tovar S, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M, Dieguez C, Castano JP, Malagon MM. Regulation of pituitary cell function by adiponectin. Endocrinology. 2007;148:401–410. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosmond R, Dallman MF, Bjorntorp P. Stress-related cortisol secretion in men: relationships with abdominal obesity and endocrine, metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1853–1859. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchenko PE. Adrenalectomy-induced enhancement of CRF and vasopressin immunoreactivity in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons: anatomic, peptide, and steroid specificity. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1093–1106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-04-01093.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26746–26749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404:661–671. doi: 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Miglioretti DL, Crane PK, van Belle G, Kessler RC. ASsociation between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the us adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South T, Westbrook F, Morris MJ. Neurological and stress related effects of shifting obese rats from a palatable diet to chow and lean rats from chow to a palatable diet. Physiol Behav. 2012;105:1052–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE. Hypothalamic integration: organization of the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1983;6:269–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.06.030183.001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taicher GZ, Tinsley FC, Reiderman A, Heiman ML. Quantitative magnetic resonance (QMR) method for bone and whole-body-composition analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;377:990–1002. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Lai YM, Christiansen AM, Ostrander MM, Jones AA, Jones KR, Choi DC, Krause EG, Evanson NK, Furay AR, Davis JF, Solomon MB, de Kloet AD, Tamashiro KL, Sakai RR, Seeley RJ, Woods SC, Herman JP. Pleasurable behaviors reduce stress via brain reward pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20529–20534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007740107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:397–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viengchareun S, Penfornis P, Zennaro MC, Lombes M. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors inhibit UCP expression and function in brown adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E640–649. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.4.E640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeburg SA, Hoogendijk WJ, van Pelt J, Derijk RH, Verhagen JC, van Dyck R, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Penninx BW. Major depressive disorder and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: Results from a large cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:617–626. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlestedt C, Skagerberg G, Ekman R, Heilig M, Sundler F, Hakanson R. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) in the area of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus activates the pituitary-adrenocortical axis in the rat. Brain Res. 1987;417:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZV, Deng Y, Wang QA, Sun K, Scherer PE. Identification and characterization of a promoter cassette conferring adipocyte-specific gene expression. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2933–2939. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SC, Gotoh K, Clegg DJ. Gender Differences in the Control of Energy Homeostasis. Exp Biol Med. 2003;228:1175–1180. doi: 10.1177/153537020322801012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SC, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG, Seeley RJ. Food intake and the regulation of body weight. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:255–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Matheny M, Zolotukhin S, Tumer N, Scarpace PJ. Regulation of adiponectin and leptin gene expression in white and brown adipose tissues: influence of beta3-adrenergic agonists, retinoic acid, leptin and fasting. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1584:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.