Abstract

Introduction

Two studies were carried out to investigate the efficacy and safety of luseogliflozin added to existing oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs) in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients inadequately controlled with OAD monotherapy.

Materials and Methods

In the trial involving add-on to sulfonylureas (study 03-1), patients were randomly assigned to receive luseogliflozin 2.5 mg or a placebo for a 24-week double-blind period, followed by a 28-week open-label period. In the open-label trial involving add-on to other OADs; that is, biguanides, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, glinides and α-glucosidase inhibitors (study 03-2), patients received luseogliflozin for 52 weeks.

Results

In study 03-1, luseogliflozin significantly decreased glycated hemoglobin at the end of the 24-week double-blind period compared with the placebo (–0.88%, P < 0.001), and glycated hemoglobin reduction from baseline at week 52 was –0.63%. In study 03-2, luseogliflozin added to other OADs significantly decreased glycated hemoglobin from baseline at week 52 (–0.52 to –0.68%, P < 0.001 for all OADs). Bodyweight reduction was observed in all add-on therapies, even with agents associated with weight gain, such as sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones. Most adverse events were mild in severity. When added to a sulfonylurea, incidences of hypoglycemia during the double-blind period were 8.7% and 4.2% for luseogliflozin and placebo, respectively, but no major hypoglycemic episodes occurred. The frequency and incidences of adverse events of special interest for sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and adverse events associated with combined OADs were acceptable.

Conclusions

Add-on therapies of luseogliflozin to existing OADs improved glycemic control, reduced bodyweight and were well tolerated in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients. These trials were registered with the Japan Pharmaceutical Information Center (add on to sulfonylurea: JapicCTI-111507; add on to other OADs: JapicCTI-111508).

Keywords: Add-on therapy, Luseogliflozin, Oral antidiabetic drug

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases globally. Although basic management of type 2 diabetes mellitus initially involves diet and exercise therapies, eventually patients often require treatment with oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs). For patients with insufficient glycemic control while receiving conventional OAD monotherapy, combination therapy with another OAD having a different mechanism of action, glucagon-like peptide-1 analog, or insulin might be required1. As many patients fail to achieve glycemic goals despite treatment with multiple drugs, a new class of antidiabetic agent is needed.

Inhibition of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) increases urinary glucose excretion (UGE) and reduces plasma glucose levels by suppressing reabsorption of glucose at the renal proximal tubules2–4. As the mechanism of action of SGLT2 inhibitors is markedly different from that of other OADs, this makes its combined use with any other OADs possible and thereby provides the additional glucose-lowering effect. Indeed, the efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors added to metformin has been evaluated by several clinical trials in Europe and the USA5–7, where metformin is usually used as the first-line drug for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. In Japanese clinical settings, in contrast, various different initial combination therapies are possible, as the choice of OADs is tailored to the condition of the patients, thus clinical trials investigating the combination therapies with the numerous existing OADs are required.

Sulfonylurea (SU) is frequently used for many diabetic patients, as insulin hyposecretion is regarded as the main pathogenetic mechanism for the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Japanese population8, so SGLT2 inhibitors are very likely to be added to SU therapy in Japan. Combination therapy of SGLT2 inhibitor with SU, however, could possibly increase the frequency or enhance the intensity of hypoglycemia, a typical side-effect of SU, such as the serious hypoglycemia seen when dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i) are co-administered with SU9. Furthermore, evaluations of whether combining SGLT2 inhibitors with OADs other than SU increases the risk of the major side-effects of these drugs (e.g. weight gain, edema, lactic acidosis, gastrointestinal disorders) are also required, along with assessments of whether the risk of the prevalent adverse drug reactions of SGLT2 inhibitors increases when added to other OADs.

Luseogliflozin is a novel and selective SGLT2 inhibitor. In our 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, luseogliflozin monotherapy was associated with marked improvements in glycemic control and was well tolerated in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus10. Thus, we carried out two 52-week trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of luseogliflozin as add-on therapy to every existing OAD that is available in Japanese clinical settings, which are the SUs, biguanides (BGs), DPP4i, thiazolidinediones (TZDs), glinides and α-glucosidase inhibitors (α-GIs).

In the trial involving add-on to SU (study 03-1), luseogliflozin 2.5 mg or a placebo was administered during a 24-week double-blind period, followed by administration of luseogliflozin for a 28-week open-label period (52 weeks in total). In the trial involving add-on to OADs other than SU (study 03-2), luseogliflozin was administered to all patients during a 52-week open-label treatment period.

Materials and Methods

These two studies were carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of all participating medical institutions, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects participating in the studies. The equivalent National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program value (%) of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was calculated using the Japan Diabetes Society-assigned value11. These studies were registered beforehand at the Japan Pharmaceutical Information Center (add on to SU: JapicCTI-111507; add on to other OADs: JapicCTI-111508). The list of study sites and principle investigators are included in the supporting information (Tables S1 and S2).

Study Design

Aimed at investigating the efficacy and safety of luseogliflozin added to other OADs, two studies were carried out where luseogliflozin was given as an add-on to SU (study 03-1) or to other OADs (BG, DPP4i, TZD, glinide, α-GI; study 03-2). These studies were designed by referring to the Japanese guidelines for the clinical evaluation of OADs and long-term treatment12,13.

Both studies enrolled Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in whom plasma glucose control was inadequate on diet and exercise therapies, and treatment with a single OAD (SU: glimepiride, BG: metformin, DPP4i: sitagliptin, vildagliptin or alogliptin, TZD: pioglitazone, glinide: mitiglinide or nateglinide, α-GI: voglibose or miglitol). Study 03-1 (add-on to SU) was a multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group comparative study. Study participants were randomized at a ratio of 2:1 to receive either luseogliflozin 2.5 mg or a placebo (i.e. glimepiride alone) before breakfast once daily. All participants that completed the 4-week observation period and 24-week double-blind treatment period proceeded to the 28-week open-label treatment period and received luseogliflozin. Study 03-2 (add-on to other OADs) was a multicenter, open-label, uncontrolled study in which all participants received luseogliflozin 2.5 mg before breakfast once daily for 52 weeks. In both studies, for patients whose HbA1c was ≥7.4% at both weeks 16 and 20, the dose of luseogliflozin was allowed to be increased to 5 mg. Both studies were carried out from May 2011 to October 2012; 46 medical institutions participated in study 03-1 (add-on to SU) and 68 medical institutions participated in study 03-2 (add-on to other OADs).

Patients

Of the type 2 diabetic patients who had received regular diet therapy and treatment with a single OAD at a fixed dose from over 8 weeks before the observation period, those aged ≥20 years in whom HbA1c was 6.9–10.5% and its change was within 1.0% during the 4-week observation period were selected as study participants. Major exclusion criteria were: the presence of diabetes other than type 2; endocrine disorders other than diabetes that might affect plasma glucose; implementation of diabetic treatment within 8 weeks before the initiation of the observation period; history of nephrectomy or renal transplantation; renal disorder requiring active treatment; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <45 mL/min/1.73 m2 during the observation period; urinary tract or genital infection; the presence of obvious dysuria; elevation of aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase to ≥2.5-fold the upper limit of normal; blood pressure >170/100 mmHg; change in antihypertensive agent during the observation period; diabetic microangiopathy; and severe heart disease. Use of an insulin product and an antidiabetic agent other than those coadministered in the study was prohibited. Use of a hypolipidemic agent, an antihypertensive agent or a diuretic agent was permitted as long as the dose was kept constant throughout the study period.

Clinical Evaluations

Major efficacy end-points were the changes from baseline (week 0) in HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and bodyweight. The safety end-points were the nature and frequency of adverse events (AEs), including changes in laboratory values, vital signs and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) findings. During the study period, participants visited medical institutions at weeks 0, 2 and 4, and every 4 weeks thereafter until week 52 to undergo medical examination, laboratory tests (hematology, blood chemistry and urinalysis), physical examinations (blood pressure, pulse rate and body temperature) and 12-lead ECG examination. When an AE was observed, its description, severity, seriousness, causal relationship to the study drug and other pertinent information were recorded. All laboratory tests were analyzed at a central laboratory.

Statistical Analyses

Efficacy and safety assessments were carried out in all participants who received the study drug at least once and underwent examination/observation for the post-administration assessment.

Basic statistics of each efficacy end-point were calculated at each evaluation point in both studies. In study 03-1 (add-on to SU), differences between the luseogliflozin group and placebo group in changes in efficacy end-points at the end of the 24-week double-blind treatment period were evaluated. For the evaluation of HbA1c and FPG, analysis of covariance was carried out using the value at the start of the double-blind treatment period as the covariate, and for the evaluation of other efficacy end-points, two-sample t-test was applied. When data were missing or deemed unacceptable at week 24 (the end of the double-blind treatment period), the last observation carried forward method was applied. In addition, for each type of co-administered OAD, within-group mean changes from baseline (week 0) for individual efficacy end-points were evaluated by the one-sample t-test (missing or unacceptable data were not complemented). In both analyses, significance level was set at 5% (two-sided) and confidence coefficient was set at 95% (two-sided).

Adverse events observed were coded using the Japanese version of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 15.0, and their frequencies during the 52-week treatment period were tabulated by the type of coadministered OAD. In study 03-1, incidence rates of AEs in the luseogliflozin group and placebo group during the 24-week double-blind treatment period were also tabulated.

Basic statistics of laboratory values, vital signs and 12-lead ECG findings by the type of coadministered antidiabetic agent at each evaluation point through week 52 were calculated.

Results

Demographics

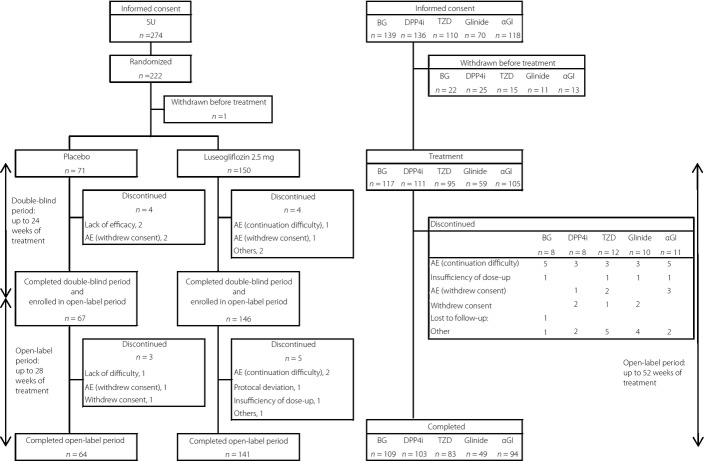

A total of 222 patients were randomized to either the placebo or luseogliflozin group in study 03-1, and 59–117 patients were administered luseogliflozin in each OAD group in study 03-2 (Figure1). The mean age of each OAD group in study 03-2 (add-on to other OADs) was 57.7–60.8 years, and the percentages of male participants were 58.1–69.5%, whereas the mean HbA1c values at baseline were similar across all groups (7.84–8.00%; Table1). Similarly, no differences were seen between the luseogliflozin group and placebo group in study 03-1 (add-on to SU).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. AE, adverse event; BG, biguanide; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione; α-GI, α-glucosidase inhibitor.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients

| Study 03-1 | Study 03-2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SU | BG | DPP4i | TZD | Glinide | α-GI | ||

| Placebo n = 71 | Luseogliflozin n = 150 | n = 117 | n = 111 | n = 95 | n = 59 | n = 105 | |

| Age (years) | 59.9 ± 10.5 | 61.2 ± 8.4 | 57.7 ± 10.6 | 58.9 ± 10.8 | 60.8 ± 11.0 | 60.1 ± 13.1 | 60.4 ± 11.1 |

| Sex (male) | 48 (67.6%) | 112 (74.7%) | 68 (58.1%) | 75 (67.6%) | 66 (69.5%) | 38 (64.4%) | 70 (66.7%) |

| Weight (kg) | 65.34 ± 10.57 | 66.39 ± 11.48 | 69.40 ± 13.07 | 67.62 ± 14.45 | 71.67 ± 13.40 | 66.38 ± 12.71 | 66.19 ± 12.90 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.66 ± 3.31 | 24.78 ± 3.63 | 26.05 ± 3.54 | 25.25 ± 3.89 | 26.88 ± 4.35 | 25.37 ± 4.18 | 25.12 ± 3.79 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.01 ± 0.73 | 8.07 ± 0.85 | 7.84 ± 0.71 | 7.88 ± 0.78 | 7.95 ± 0.92 | 8.00 ± 0.88 | 7.85 ± 0.77 |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 148.2 ± 28.3 | 151.1 ± 32.7 | 143.8 ± 24.8 | 152.1 ± 30.7 | 141.7 ± 29.9 | 146.9 ± 31.2 | 148.0 ± 27.0 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 7.9 ± 6.6 | 7.4 ± 5.6 | 5.8 ± 4.4 | 6.2 ± 5.7 | 7.1 ± 5.6 | 6.6 ± 5.6 | 6.6 ± 6.0 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 84.3 ± 16.3 | 81.5 ± 17.3 | 85.9 ± 20.6 | 82.5 ± 17.2 | 80.1 ± 14.1 | 84.5 ± 19.9 | 80.2 ± 15.9 |

α-GI, α-glucosidase inhibitor

BG, biguanide

BMI, body mass index

DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

FPG, fasting plasma glucose

HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c

HOMA-β, homeostasis model assessment of β-cell function

SD, standard deviation

SU, sulfonylurea

TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Data represent mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Efficacy

Efficacy of Luseogliflozin Add-On to SU (Study 03-1)

Luseogliflozin significantly reduced HbA1c from baseline compared with the placebo, with the difference being –0.88% (P < 0.001) at week 24 (the end of the double-blind period; Figure2). Similarly, the differences in the change in FPG and bodyweight compared with the placebo at week 24 were –34.2 mg/dL and –1.51 kg, respectively, where both differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001 for both end-points; Figure S1). After 52 weeks of luseogliflozin treatment, HbA1c, FPG and bodyweight were significantly lower than baseline, with the mean change being –0.63%, –22.4 mg/dL and –2.23 kg, respectively.

Figure 2.

Changes in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) at week 24 for the luseogliflozin and placebo groups in study 03-1, and at week 52 for each oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) group in studies 03-1 and 03-2. Data at week 24 represent mean ± 95% confidence interval, and data at week 52 are mean ± standard error. Differences in least squares (LS) mean change with luseogliflozin relative to placebo at week 24 (LS mean [95% confidence interval], last observation carried forward [LOCF]) was –0.88 [–1.0 to –0.7]%. †P < 0.001 vs placebo. *P < 0.001 vs baseline. BG, biguanide; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; LUSEO, luseogliflozin; PBO, placebo; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione; α-GI, α-glucosidase inhibitor.

Efficacy of Luseogliflozin Add-On to Other OADs (Study 03-2)

Luseogliflozin lowered HbA1c when it was added to any of the OADs (Figure2). Significant lowering of HbA1c was maintained from week 2 through to week 52 when compared with baseline in all the OAD groups, with the mean change in HbA1c from baseline at week 52 being –0.61, –0.52, –0.60, –0.59, and –0.68% for the BG, DPP4i, TZD, Glinide and α-GI groups, respectively (P < 0.001 for all groups). Similarly, the decrease in FPG and bodyweight from baseline at week 52 in each OAD group was –21.4 to –17.8 mg/dL and –2.88 to –1.96 kg, respectively, with luseogliflozin significantly lowering the FPG and bodyweight in all these groups (P < 0.001 for all groups; Figure S1).

Safety

Safety During the 24-Week Double-Blind Period (Study 03-1)

The incidence of AEs and adverse drug reactions (ADRs) during 24 weeks of treatment with luseogliflozin add-on to SU (59.3% and 17.3%) was similar to that of the placebo group (64.8% and 15.5%). Serious AEs (SAEs) were observed in five participants in the luseogliflozin group, but none of these events were considered to be drug-related. Adverse events that led to discontinuation occurred in two participants each in the luseogliflozin group and the placebo group. However, none of these AEs in the luseogliflozin group were considered to be drug-related.

Safety at Week 52 of Treatment (Study 03-1, 03-2)

The incidence of AEs was 71.2–84.2% when luseogliflozin was added to each of the OADs for 52 weeks, whereas ADRs occurred in 12.4–25.4% of patients (Table2). Common AEs (AEs with an incidence ≥5% in any of the OAD groups) were constipation, nasopharyngitis, pharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, contusion, albumin urine present, β2 microglobulin urine increased, C-reactive protein increased, blood urine present, white blood cells urine positive, blood ketone body increased, urine ketone body present, hypoglycemia and back pain. Most of the AEs were of mild severity, and SAEs were observed in 3–11 participants in each OAD group. There was one participant who died in the SU co-administration group (Study 03-1) as a result of acute myocardial infarction that was considered not to be drug-related. A total of five serious ADRs were observed in the studies; these were myocardial infarction (SU), angina unstable (α-GI), acute myocardial infarction (α-GI), prostatitis (TZD) and drug eruption (glinide). Adverse events led to discontinuation in four to eight participants in each OAD group.

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events

| Study 03-1 | Study 03-2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SU | BG | DPP4i | TZD | Glinide | α-GI | |

| n | 150 | 117 | 111 | 95 | 59 | 105 |

| Any AE | 122 (81.3) | 92 (78.6) | 82 (73.9) | 80 (84.2) | 42 (71.2) | 79 (75.2) |

| Any ADR | 32 (21.3) | 23 (19.7) | 21 (18.9) | 20 (21.1) | 15 (25.4) | 13 (12.4) |

| Death | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other serious AEs | 9 (6.0) | 11 (9.4) | 4 (3.6) | 7 (7.4) | 3 (5.1) | 7 (6.7) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 4 (2.7) | 5 (4.3) | 5 (4.5) | 5 (5.3) | 4 (6.8) | 8 (7.6) |

| Common AEs (AEs with an incidence ≥5% in any of the OAD groups) | ||||||

| Constipation | 8 (5.3) | 8 (6.8) | 1 (0.9) | 5 (5.3) | 0 | 2 (1.9) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 47 (31.3) | 38 (32.5) | 31 (27.9) | 34 (35.8) | 15 (25.4) | 36 (34.3) |

| Pharyngitis | 8 (5.3) | 4 (3.4) | 1 (0.9) | 7 (7.4) | 0 | 2 (1.9) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 8 (5.3) | 10 (8.5) | 5 (4.5) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (3.4) | 5 (4.8) |

| Contusion | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.7) | 5 (4.5) | 6 (6.3) | 0 | 2 (1.9) |

| Albumin urine present | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.9) | 6 (5.4) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (3.4) | 1 (1.0) |

| β2 microglobulin urine increased | 8 (5.3) | 4 (3.4) | 9 (8.1) | 6 (6.3) | 2 (3.4) | 4 (3.8) |

| C-reactive protein increased | 14 (9.3) | 10 (8.5) | 11 (9.9) | 16 (16.8) | 4 (6.8) | 5 (4.8) |

| Blood urine present | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (3.6) | 7 (7.4) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.0) |

| White blood cells urine positive | 2 (1.3) | 5 (4.3) | 4 (3.6) | 7 (7.4) | 2 (3.4) | 0 |

| Blood ketone body increased | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.6) | 2 (1.8) | 5 (5.3) | 6 (10.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Urine ketone body present | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.6) | 2 (1.8) | 3 (3.2) | 4 (6.8) | 1 (1.0) |

| Hypoglycemia | 16 (10.7) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (3.4) | 3 (2.9) |

| Back pain | 5 (3.3) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (3.6) | 6 (6.3) | 1 (1.7) | 3 (2.9) |

| Special interest AEs | ||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 16 (10.7) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (3.4) | 3 (2.9) |

| Urinary tract infections† | 0 | 4 (3.4) | 3 (2.7) | 5 (5.3) | 2 (3.4) | 1 (1.0) |

| Male | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Female | 0 | 3 (6.1) | 3 (2.9) | 4 (8.3) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (9.5) |

| Genital infections‡ | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.7) | 0 |

| Male | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Female | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (4.8) | 0 |

| Pollakiuria | 4 (2.7) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (3.4) | 2 (1.9) |

| AEs related to volume depletion§ | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

α-GI, α-glucosidase inhibitor

ADR, adverse drug reaction

AE, adverse event

BG, biguanide

DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor

OAD, oral antidiabetic drug

SAE, serious adverse event

SU, sulfonylurea

TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Data represent n (%).

Includes cystitis, pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection and cystitis bacterial.

Includes genital candidiasis, vulvitis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, vaginitis bacterial and prostatitis.

Includes thirst, blood pressure decreased, blood potassium increased, blood urea increased, blood uric acid increased, dehydration, hypotension and orthostatic hypotension.

Hypoglycemia

The incidence of hypoglycemia in Study 03-1 was 8.7% when luseogliflozin was added to SU for 24 weeks, which was higher than the placebo group (4.2%; Table S3). Meanwhile, the incidence of hypoglycemia was 10.7% over 52 weeks of add-on therapy, where no obvious increase with long-term administration was observed. The incidence of hypoglycemia in participants who received a high dose of SU (≥3 mg) was 8.3% (2/24) compared with 8.7% (11/126) in those who received a low dose (<3 mg). There were no hypoglycemic events that were serious or severe enough to require the assistance of another person. All hypoglycemia recovered rapidly with either food or oral glucose intake, and no participants discontinued because of hypoglycemia.

The incidence of hypoglycemia in the other OAD groups in Study 03-2 was 0.9–3.4% (Table2). Cases of hypoglycemia in these OAD groups were mild in severity, and no cases of hypoglycemia that were serious or severe enough to require the assistance of another person were observed. One participant in the α-GI co-administration group discontinued because of hypoglycemia.

Urinary Tract and Genital Infections

The incidences of urinary tract infections and genital infections in each of the OAD groups over 52 weeks were 0–5.3% and 0–2.1%, respectively (Table2). Most of these infections were mild in severity, although prostatitis reported in one participant in the TZD co-administration group was serious. All the infections resolved spontaneously or with antibiotic treatment, and no participants discontinued as a result of an infection.

Pollakiuria and Volume Depletion

The incidences of AEs related to pollakiuria or volume depletion in each of the OAD groups over 52 weeks were 0.9–3.4% and 0–1.8%, respectively (Table2). All these AEs were mild, except for one moderate case of hypotension in the BG co-administration group, and no SAEs were observed. One participant in the TZD co-administration group discontinued because of mild pollakiuria and dehydration. Hematocrit and blood urea nitrogen were seen to be higher than baseline in all the OAD groups (Table3).

Table 3.

Changes in laboratory test values at week 52

| Study 03-1 | Study 03-2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SU | BG | DPP4i | TZD | Glinide | α-GI | |||||||

| n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | |

| Hematocrit (%) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 42.02 ± 3.76 | 117 | 41.57 ± 3.21 | 111 | 41.60 ± 3.97 | 95 | 40.62 ± 4.15 | 59 | 40.99 ± 3.76 | 105 | 41.48 ± 3.74 |

| Week 52 | 140 | 43.99 ± 4.01 | 109 | 43.83 ± 3.72 | 103 | 43.67 ± 4.12 | 83 | 42.74 ± 4.17 | 49 | 43.31 ± 3.91 | 94 | 43.98 ± 4.06 |

| Change from BL | 2.03 (1.7, 2.4) | 2.24 (1.8, 2.7) | 1.86 (1.5, 2.2) | 2.11 (1.7, 2.5) | 2.70 (2.1, 3.3) | 2.67 (2.2, 3.1) | ||||||

| BUN (mg/dL) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 14.9 ± 3.9 | 117 | 14.3 ± 3.8 | 111 | 15.0 ± 4.1 | 95 | 15.1 ± 4.0 | 59 | 14.5 ± 4.2 | 105 | 14.1 ± 4.2 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 17.3 ± 4.6 | 109 | 16.6 ± 4.2 | 103 | 16.2 ± 3.8 | 83 | 16.6 ± 4.4 | 49 | 16.5 ± 4.5 | 94 | 16.4 ± 5.1 |

| Change from BL | 2.4 (2, 3) | 2.4 (2, 3) | 1.2 (1, 2) | 1.5 (1, 2) | 2.1 (1, 3) | 2.4 (2, 3) | ||||||

| NAG (U/L) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 10.10 ± 8.60 | 117 | 9.79 ± 7.25 | 111 | 9.94 ± 9.45 | 95 | 10.97 ± 8.85 | 59 | 9.19 ± 5.92 | 105 | 9.95 ± 7.99 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 9.48 ± 7.53 | 109 | 9.88 ± 7.20 | 103 | 8.32 ± 5.50 | 83 | 10.33 ± 5.99 | 49 | 7.72 ± 5.37 | 94 | 9.71 ± 8.18 |

| Change from BL | −0.45 (−1.7, 0.8) | 0.00 (−1.4, 1.4) | −1.47 (−3.2, 0.3) | −0.71 (−2.3, 0.9) | −1.24 (−3.1, 0.7) | −0.27 (−2.2, 1.7) | ||||||

| β2-microglobulin (μg/L) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 194.8 ± 226.2 | 117 | 175.5 ± 244.9 | 111 | 143.4 ± 145.8 | 95 | 173.5 ± 184.2 | 59 | 167.1 ± 187.8 | 105 | 250.7 ± 870.2 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 265.8 ± 457.4 | 109 | 199.1 ± 356.3 | 103 | 154.6 ± 128.6 | 83 | 287.1 ± 667.2 | 49 | 187.7 ± 306.7 | 94 | 227.4 ± 372.6 |

| Change from BL | 73.1 (7, 139) | 35.1 (−1, 71) | 19.7 (−6, 46) | 112.1 (−17, 241) | 16.3 (−65, 97) | −31.1 (−189, 127) | ||||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 81.5 ± 17.3 | 117 | 85.9 ± 20.6 | 111 | 82.5 ± 17.2 | 95 | 80.1 ± 14.1 | 59 | 84.5 ± 19.9 | 105 | 80.2 ± 15.9 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 80.7 ± 17.9 | 109 | 86.0 ± 20.1 | 103 | 82.8 ± 18.2 | 83 | 80.4 ± 14.2 | 49 | 83.6 ± 21.1 | 94 | 79.7 ± 16.2 |

| Change from BL | −0.24 (−1.7, 1.2) | −0.74 (−2.3, 0.9) | −0.19 (−1.8, 1.5) | 0.41 (−1.2, 2.0) | −0.65 (−3.2, 1.9) | −0.62 (−2.1, 0.9) | ||||||

| AST (IU/L) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 24.6 ± 8.1 | 117 | 25.5 ± 9.7 | 111 | 26.0 ± 10.2 | 95 | 26.2 ± 8.9 | 59 | 24.3 ± 10.3 | 105 | 24.6 ± 9.0 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 23.7 ± 7.2 | 109 | 22.3 ± 6.4 | 103 | 24.2 ± 6.8 | 83 | 24.0 ± 9.8 | 49 | 22.0 ± 6.1 | 94 | 23.3 ± 5.8 |

| Change from BL | −1.1 (−2, 0) | −3.0 (−5, −1) | −2.0 (−4, −1) | −1.9 (−4, 0) | −2.2 (−4, 0) | −1.6 (−3, 0) | ||||||

| ALT (IU/L) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 25.6 ± 13.0 | 117 | 30.5 ± 20.3 | 111 | 26.9 ± 16.5 | 95 | 25.0 ± 13.8 | 59 | 26.5 ± 16.1 | 105 | 29.8 ± 17.7 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 21.8 ± 8.4 | 109 | 22.6 ± 13.0 | 103 | 23.6 ± 12.5 | 83 | 19.9 ± 8.1 | 49 | 20.4 ± 11.0 | 94 | 23.9 ± 10.3 |

| Change from BL | −4.1 (−6, −2) | −7.2 (−10, −4) | −4.1 (−6, −2) | −4.8 (−7, −3) | −5.9 (−9, −3) | −5.6 (−8, −3) | ||||||

| γ-GTP (IU/L) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 46.5 ± 35.9 | 117 | 42.4 ± 36.7 | 111 | 46.2 ± 38.4 | 95 | 37.1 ± 31.9 | 59 | 43.7 ± 64.8 | 105 | 43.2 ± 37.1 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 37.7 ± 29.5 | 109 | 34.2 ± 38.1 | 103 | 42.7 ± 37.1 | 83 | 33.7 ± 41.2 | 49 | 40.1 ± 78.4 | 94 | 34.5 ± 32.0 |

| Change from BL | −9.6 (−13, −6) | −7.5 (−13, −2) | −5.5 (−9, −2) | −4.1 (−9, 1) | −5.5 (−11, 0) | −9.3 (−13, −6) | ||||||

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 145.1 ± 93.9 | 117 | 156.4 ± 122.3 | 111 | 134.5 ± 104.4 | 95 | 123.8 ± 84.1 | 59 | 147.8 ± 98.2 | 105 | 138.3 ± 118.3 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 137.6 ± 115.7 | 109 | 128.8 ± 87.0 | 103 | 117.0 ± 84.6 | 83 | 115.9 ± 72.6 | 49 | 125.5 ± 81.4 | 94 | 113.8 ± 116.4 |

| Change from BL | −10.1 (−23, 3) | −27.8 (−52, −4) | −21.6 (−36, −7) | −12.2 (−26, 1) | −24.2 (−42, −6) | −26.2 (−42, −10) | ||||||

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 118.7 ± 26.2 | 117 | 113.9 ± 26.4 | 111 | 116.7 ± 29.3 | 95 | 112.6 ± 29.2 | 59 | 115.5 ± 25.4 | 105 | 115.0 ± 27.7 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 121.4 ± 26.0 | 109 | 117.2 ± 26.4 | 103 | 117.7 ± 27.7 | 83 | 112.5 ± 24.6 | 49 | 121.0 ± 22.9 | 94 | 119.4 ± 28.5 |

| Change from BL | 2.6 (−1, 6) | 4.9 (1, 9) | 0.5 (−4, 5) | 0.5 (−4, 5) | 5.7 (−1, 12) | 4.8 (0, 9) | ||||||

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 56.5 ± 14.2 | 117 | 54.6 ± 13.3 | 111 | 57.9 ± 16.1 | 95 | 61.5 ± 15.6 | 59 | 56.0 ± 16.6 | 105 | 53.7 ± 14.2 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 61.2 ± 16.5 | 109 | 59.9 ± 15.3 | 103 | 63.2 ± 16.0 | 83 | 67.7 ± 20.2 | 49 | 59.1 ± 15.1 | 94 | 60.8 ± 15.8 |

| Change from BL | 4.8 (4, 6) | 4.9 (3, 7) | 5.8 (4, 7) | 6.3 (4, 8) | 3.4 (1, 6) | 6.5 (5, 8) | ||||||

| LDL/HDL ratio | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 2.242 ± 0.744 | 117 | 2.210 ± 0.746 | 111 | 2.125 ± 0.645 | 95 | 2.006 ± 0.960 | 59 | 2.189 ± 0.668 | 105 | 2.265 ± 0.755 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 2.144 ± 0.779 | 109 | 2.078 ± 0.676 | 103 | 1.972 ± 0.650 | 83 | 1.850 ± 0.839 | 49 | 2.176 ± 0.668 | 94 | 2.072 ± 0.658 |

| Change from BL | −0.106 (−0.19, −0.02) | −0.089 (−0.17, −0.01) | −0.164 (−0.25, −0.08) | −0.158 (−0.24, −0.07) | −0.014 (−0.14, 0.11) | −0.153 (−0.24, −0.06) | ||||||

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 6.74 ± 3.21 | 117 | 6.06 ± 2.63 | 111 | 7.25 ± 4.53 | 95 | 15.24 ± 9.92 | 59 | 7.11 ± 3.35 | 105 | 7.19 ± 3.72 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 7.43 ± 3.75 | 109 | 6.83 ± 3.26 | 103 | 7.36 ± 3.44 | 83 | 17.27 ± 12.98 | 49 | 7.90 ± 3.40 | 94 | 8.25 ± 4.46 |

| Change from BL | 0.75 (0.5, 1.0) | 0.83 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.72 (0.5, 1.0) | 2.00 (1.0, 3.0) | 0.67 (0.3, 1.1) | 1.03 (0.7, 1.4) | ||||||

| Acetoacetic acid (μmol/L) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 36.3 ± 27.3 | 117 | 33.6 ± 26.4 | 111 | 35.3 ± 23.8 | 95 | 41.0 ± 36.9 | 59 | 35.8 ± 25.6 | 105 | 32.6 ± 24.2 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 65.2 ± 49.2 | 109 | 59.3 ± 70.6 | 103 | 56.6 ± 42.1 | 83 | 52.9 ± 43.5 | 49 | 63.2 ± 64.0 | 94 | 55.6 ± 47.5 |

| Change from BL | 29.0 (21, 37) | 25.4 (13, 37) | 22.2 (14, 30) | 10.2 (−1, 21) | 27.4 (11, 44) | 22.9 (13, 33) | ||||||

| β-hydroxybutyric acid (μmol/L) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 78.8 ± 69.5 | 117 | 74.1 ± 79.6 | 111 | 75.9 ± 68.4 | 95 | 96.2 ± 109.5 | 59 | 81.6 ± 74.6 | 105 | 72.7 ± 79.4 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 151.5 ± 143.8 | 109 | 140.5 ± 244.5 | 103 | 129.3 ± 132.3 | 83 | 140.2 ± 194.0 | 49 | 160.4 ± 170.1 | 94 | 136.5 ± 158.7 |

| Change from BL | 73.2 (49, 97) | 65.3 (24, 106) | 56.3 (30, 82) | 39.4 (−6, 85) | 79.8 (36, 123) | 64.2 (32, 96) | ||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 128.9 ± 15.2 | 117 | 126.5 ± 13.8 | 111 | 126.4 ± 13.4 | 95 | 132.3 ± 15.5 | 59 | 127.8 ± 15.6 | 105 | 128.5 ± 15.4 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 124.7 ± 15.0 | 109 | 122.4 ± 13.4 | 103 | 123.0 ± 13.0 | 83 | 124.7 ± 13.1 | 49 | 123.7 ± 14.4 | 94 | 122.7 ± 14.6 |

| Change from BL | −4.4 (−7, −2) | −4.1 (−7, −2) | −3.2 (−6, −1) | −8.3 (−11, −6) | −4.8 (−9, −1) | −6.3 (−9, −4) | ||||||

| DBP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 150 | 75.1 ± 8.6 | 117 | 76.3 ± 10.4 | 111 | 74.9 ± 9.6 | 95 | 76.1 ± 10.7 | 59 | 73.5 ± 10.3 | 105 | 76.2 ± 10.8 |

| Week 52 | 141 | 73.7 ± 9.2 | 109 | 75.1 ± 9.9 | 103 | 73.9 ± 9.8 | 83 | 71.7 ± 10.0 | 49 | 71.1 ± 9.9 | 94 | 72.5 ± 8.8 |

| Change from BL | −1.7 (−3, 0) | −1.1 (−3, 1) | −0.8 (−3, 1) | −4.5 (−6, −3) | −3.2 (−5, −1) | −3.9 (−6, −2) | ||||||

ALT, alanine aminotransferase

AST, aspartate aminotransferase

BG, biguanide

BUN, blood urea nitrogen

CI, confidence interval

DBP, diastolic blood pressure

DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

NAG, N-acetyl-D-glucosaminidase

SBP, systolic blood pressure

SU, sulfonylurea

TZD, thiazolidinedione

α-GI, α-glucosidase inhibitor

γ-GTP, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase. Values at baseline (BL) and week 52 represent mean ± standard deviation (SD), and changes from BL represent mean (95% confidence interval).

Adverse Events Associated With Each OAD

Edema, a known side-effect of TZDs, did not occur in the TZD co-administration group. Similarly, lactic acidosis, a side-effect of BGs, was also not observed in the present study. While gastrointestinal symptoms, such as constipation, diarrhea, vomiting and gastritis, are known side-effects of α-GI and BG, most of these gastrointestinal AEs were mild in severity in these groups.

Laboratory Tests and Vital Signs

Mild elevation in urinary β2 microglobulin was observed in all the OAD groups, although the level of increase did not suggest tubular impairment, as urinary N-acetyl-D-glucosaminidase was not elevated (Table3). In addition, marked changes in the eGFR were not observed in any of the OAD groups. In all the groups, blood ketone bodies were elevated, whereas aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and triglyceride levels were decreased compared with baseline. Although low-density lipoprotein levels were slightly increased, the low-density lipoprotein/high-density lipoprotein ratio decreased as a result of an increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in all the groups. Adiponectin levels were increased in all the groups. Decreases were seen in both the systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure across all the groups compared with baseline, especially obvious in the TZD co-administration group.

Discussion

The present study found that add-on of luseogliflozin, a SGLT2 inhibitor, to OADs with different mechanisms of action (SUs, BGs, DPP4i, TZDs, glinides, α-GIs) improved glycemic control as shown by reductions in HbA1c and FPG, and these improvements remained stable throughout 52 weeks of treatment. Thus, luseogliflozin can be a new therapeutic option not only as monotherapy, but also as add-on therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with another OAD.

In the treatment of diabetes, bodyweight, blood pressure and serum lipids also need to be managed in addition to glycemic control1. Significant and sustained weight loss with luseogliflozin was observed in all OAD groups. Luseogliflozin in combination with OADs was also associated with decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, increase in adiponectin and improvement in serum lipids (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride). Thus, luseogliflozin is considered to have beneficial effects on these parameters in addition to its glucose-lowering effect independent of the background therapies. This is particularly important, because traditional therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus result in either weight gain or no changes in weight1, therefore the added benefit of weight loss with luseogliflozin could be clinically meaningful.

It is expected that luseogliflozin will have the potential to ameliorate weight gain and edema, the major side-effects of other OADs. Some of the existing OADs (SU and TZD) are known to be associated with weight gain14,15, and this poses a clinical problem as the number of therapeutic options are limited by their side-effects. The finding that luseogliflozin reduced bodyweight even as add-on to SU and TZD, which cause weight gain, is noteworthy, and luseogliflozin will benefit those patients who are receiving these OADs. Furthermore, TZD has been reported to have side-effects, such as edema, which is induced by increased reabsorption of sodium in the renal tubules through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ16. A greater decrease in blood pressure in patients who received the luseogliflozin-TZD combination than those in other OAD groups was observed in the present study. As the reduction in blood pressure was considered to be related to the putative diuretic effect of luseogliflozin, it might partially contribute to the additional decrease in blood pressure in patients with fluid retention caused by TZD.

The incidence of hypoglycemia with luseogliflozin-SU combination therapy was higher than those with SU monotherapy, and it was also higher than those observed in our previous study on luseogliflozin monotherapy (2.3%)17. However, there were no major hypoglycemic episodes, and most events were mild in severity. No hypoglycemic events required assistance or led to discontinuation, and all events recovered with feeding. No prolonged hypoglycemia was reported. It should be taken into account that the mechanism of action of SUs, which is to directly stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, is associated with the highest risk of hypoglycemia among the OADs, thus the risk of hypoglycemia might naturally increase when luseogliflozin is added to SUs. In addition, because the doses of SU were not to be changed throughout the present study, the risk of hypoglycemia in real-life clinical settings where changes in SU doses could occur needs to be further investigated. Meanwhile, the incidence rates of hypoglycemia in add-on therapy to the other OADs were similar to those of luseogliflozin monotherapy10. All events were mild in severity, showing low risks of hypoglycemia in those patients.

Urinary tract and genital infections observed in patients treated with luseogliflozin add-on to other OADs were mild and recovered with appropriate treatments. A higher incidence of polyuria and signs indicating volume depletion, such as small increases in hematocrit, were observed, although only one patient who experienced polyuria and thirst discontinued. These results suggest that combination therapy with other OADs did not exacerbate AEs expected from the pharmacological action of luseogliflozin, such as urinary tract and genital infections, polyuria and volume depletion, although further investigations are required to confirm these findings.

Meanwhile, edema and lactic acidosis, which are known respective side-effects of TZDs and BGs1, did not occur in the present study. The frequencies of gastrointestinal AEs in patients receiving α-GIs or BGs were not particularly high, and most events were mild. Above all, AEs related to known side-effects of combined OADs were tolerable for patients in this study, although more long-term and large-scale investigations in patient populations covering a broader background are required.

The present study had some potential limitations. First, because no control group was included in study 03-2 and after 24 weeks of treatment in study 03-1, it is unclear whether the rate of AEs was greater than the background rate or whether changes in any of the parameters might be due to the effects of the season or other conditions. Second, the duration and sample size was insufficient to enable assessment of the risk of rare adverse events. Third, the present study only evaluated the efficacy and safety of combining luseogliflozin with OADs, and did not include insulin and GLP-1 analogs.

Luseogliflozin improved glycemic control in combination with other OADs with different mechanisms of action. With regard to safety, the incidence of hypoglycemia was slightly higher when luseogliflozin was added to SU, although no major hypoglycemia occurred. In add-on therapy with other OADs, there was no increase in the frequency and severity of AEs. In conclusion, luseogliflozin used as add-on therapy to other OADs provided additional glycemic control and was generally well tolerated.

Acknowledgments

The clinical trials described in this article, including editorial assistance provided by WDB ICO, were sponsored by Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. The authors express their appreciation and gratitude to the patients who participated in the studies, and are grateful to all investigators for their conduct of the studies. Y Seino has received consulting fees or lecture fees from Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Astellas, Takeda, Boehringer Ingelheim, Johnson & Johnson, Becton Dickinson, AstraZeneca, Taisho Toyama and Taisho. N Inagaki has received advisory board consulting fees, honoraria for lectures, grants/research support from Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Sanofi, Novartis, Dainippon Sumitomo, Kyowa Kirin, Eli Lily, Shiratori, Roche Diagnostics, Japan Diabetes Foundation, JT, Boehringer Ingelheim, Astellas, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ono, AstraZeneca, Kowa, Taisho Toyama and Taisho. M Haneda has received consulting fees or research support from Sanofi, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Takeda, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, MSD, Kyowa Kirin, Daiichi-Sankyo, Astellas, Kowa, Taisho Toyama and Taisho. K Kaku has received advisory board consulting fees, consulting fees, or research support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, Daiichi-Sankyo, Dainippon-Sumitomo, Kowa, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Takeda, Sanofi, Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Taisho Toyama and Taisho. T Sasaki has received joint research fund from Canon Inc. and consulting fees or lecture fees from Taisho Toyama and Taisho. A Fukatsu has received consulting fees or lecture fees from Taisho Toyama and Taisho. M Ubukata, S Sakai and Y Samukawa are employees of Taisho. There is no conflict of interest related to this study.

Supporting Information

Figure S1| Changes in (a) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and (b) bodyweight at week 24 for the luseogliflozin and placebo groups in study 03-1, and at week 52 for each oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) group in studies 03-1 and 03-2. Data at week 24 represent mean ± 95% confidence interval, and data at week 52 are mean ± standard error. Differences in least squares mean change with luseogliflozin relative to placebo at week 24 (least squares mean [95% confidence interval], last observation carried forward [LOCF]) were –34.2 mg/dL [–41 to –27 mg/dL] and –1.51 kg [–2.0 to –1.0 kg] for the FPG and bodyweight, respectively. †P < 0.001 vs placebo. *P < 0.001 vs baseline. BG, biguanide; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; LUSEO, luseogliflozin; PBO, placebo; SE, standard error; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione; α-GI, α-glucosidase inhibitor.

Table S1|The list of study sites and principle investigators (study 03-1: Add-on to sulfonylurea).

Table S2| The list of study sites and principle investigators (study 03-2: Add-on to other oral antidiabetic drugs).

Table S3| Details of hypoglycemia during the double-blind period in study 03-1.

References

- 1.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–1379. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanai Y, Lee WS, You G, et al. The human kidney low affinity Na+/glucose cotransporter SGLT2. Delineation of the major renal reabsorptive mechanism for D-glucose. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:397–404. doi: 10.1172/JCI116972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFronzo RA, Davidson JA, Del Prato S. The role of the kidneys in glucose homeostasis: a new path towards normalizing glycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harada N, Inagaki N. Role of sodium-glucose transporters in glucose uptake of the intestine and kidney. J Diabetes Invest. 2012;3:352–353. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey CJ, Gross JL, Hennicken D, et al. Dapagliflozin add-on to metformin in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 102-week trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:43. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavalle-González FJ, Januszewicz A, Davidson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin compared with placebo and sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes on background metformin monotherapy: a randomised trial. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2582–2592. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3039-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridderstråle M, Svaerd R, Zeller C, et al. Rationale, design and baseline characteristics of a 4-year (208-week) phase III trial of empagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, versus glimepiride as add-on to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with insufficient glycemic control. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:129. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kodama K, Tojjar D, Yamada S, et al. Ethnic differences in the relationship between insulin sensitivity and insulin response: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1789–1796. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura T, Shiosakai K, Takeda Y, et al. Quantitative evaluation of compliance with recommendation for sulfonylurea dose co-administered with DPP-4 inhibitors in Japan. Pharmaceutics. 2012;4:479–493. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics4030479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seino Y, Sasaki T, Fukatsu A, et al. Efficacy and safety of luseogliflozin as monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:1245–1255. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.912983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashiwagi A, Kasuga M, Araki E, et al. International clinical harmonization of glycated hemoglobin in Japan: from Japan Diabetes Society to National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program values. J Diabetes Invest. 2012;3:39–40. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.2010. Guideline for clinical evaluation of oral hypoglycemic agents. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare,. Available from: http://www.pmda.go.jp/kijunsakusei/guideline.html [Last accessed 17th March 2014]

- 13.1994. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: the extent of population exposure to assess clinical safety for drugs intended for long-term treatment of non-life-threatening conditions. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use.. Available from: http://www.ich.org/products/guidelines/efficacy/article/efficacy-guidelines.html [Last accessed 17th March 2014]

- 14.Phung OJ, Scholle JM, Talwar M, et al. Effect of noninsulin antidiabetic drugs added to metformin therapy on glycemic control, weight gain, and hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2010;303:1410–1418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events) Lancet. 2005;366:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endo Y, Suzuki M, Yamada H, et al. Thiazolidinediones enhance sodium-coupled bicarbonate absorption from renal proximal tubules via PPARγ-dependent nongenomic signaling. Cell Metab. 2011;13:550–561. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seino Y, Sasaki T, Fukatsu A, et al. 2013. Luseogliflozin, a selective SGLT2 inhibitor, improves glycemic control as monotherapy in Japanese patients with T2DM. Presented at the International Diabetes Federation 2013 World Diabetes Congress, Melbourne, Australia, December 2-6,. Poster P-1472.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1| Changes in (a) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and (b) bodyweight at week 24 for the luseogliflozin and placebo groups in study 03-1, and at week 52 for each oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) group in studies 03-1 and 03-2. Data at week 24 represent mean ± 95% confidence interval, and data at week 52 are mean ± standard error. Differences in least squares mean change with luseogliflozin relative to placebo at week 24 (least squares mean [95% confidence interval], last observation carried forward [LOCF]) were –34.2 mg/dL [–41 to –27 mg/dL] and –1.51 kg [–2.0 to –1.0 kg] for the FPG and bodyweight, respectively. †P < 0.001 vs placebo. *P < 0.001 vs baseline. BG, biguanide; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; LUSEO, luseogliflozin; PBO, placebo; SE, standard error; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione; α-GI, α-glucosidase inhibitor.

Table S1|The list of study sites and principle investigators (study 03-1: Add-on to sulfonylurea).

Table S2| The list of study sites and principle investigators (study 03-2: Add-on to other oral antidiabetic drugs).

Table S3| Details of hypoglycemia during the double-blind period in study 03-1.