Abstract

We present a case of single endometrial metastasis from breast invasive ductal cancer. This case was unique because the immunohistochemical staining was negative for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/neu and estrogen and progesterone receptors, and positive for cytokeratin 5/6 and epidermal growth factor receptor in the primary and metastatic tumor cells. No gross evidence of tumor was observed in other sites. We identified 12 cases of metastases to the endometrium from breast carcinoma from series and case reports in the literature between 1985 and 2014. This review indicated that hormone receptor-positive invasive lobular breast cancer cells are more likely to metastasize to the endometrium than other cell types in patients over 50 years of age.

Keywords: Basal-like breast carcinoma, endometrium, metastases

Although breast cancer metastasis to the uterus is uncommon and usually occurs during widespread metastatic disease, it may occur in some patients as the first manifestation of the disease. However, breast carcinoma is the most common extragenital cancer that metastasizes to the uterus.1 In these cases, invasive lobular cancers (ILC) are the most common histologic type.2,3 In addition, most of these tumors are estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR) positive, and these patients are treated with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. When metastasis to the uterus occurs, the myometrium is more often involved than the endometrium.1 We present a case of single endometrial metastasis from breast invasive ductal cancer (IDC). This case was unique because the immunohistochemical staining was negative for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her-2)/neu, ER and PR, and positive for cytokeratin (CK)5/6 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in the primary and metastatic tumor cells. In addition, we briefly review the literature related to endometrial metastasis of breast cancer published in English from 1985 to 2014.

Case report

A 66-year-old female presented with a complaint of abnormal uterine bleeding. The patient had a history of left breast carcinoma (diameter 2.5c) and had received a modified radical mastectomy 11 years prior. Pathological examination of the tumor revealed IDC (T2N0M0 and G3) (Fig 1a). There was no lymphovascular invasion and all 15 axillary lymph nodes were free from tumors. Immunohistochemical staining indicated that the tumor cells were: Her-2/neu, ER and PR receptor negative (so-called triple negative breast cancer, TNBC), and approximately 50%-60% of the cells were Ki-67 positive. In addition the tumor cells were positive for CK5/6 and EGFR, which indicated that the tumor was a basal-like subtype of breast cancer. The patient received three cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy composed of Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate, and Fluorouracil (the CMF protocol) after surgery. The patient then refused subsequent chemotherapy. No endocrine-therapy was advised. She had no family history of breast cancer. Menopause had occurred at the age of 49, and there was no history of gynecologic problems. Several tumor biomarker levels were evaluated and the carcinoembryonic antigen level was increased [33.6 ng/mL (0–3)], while the levels of cancer antigen (CA)-153 and CA-125 were normal. Computed tomography and ultrasound revealed that the uterus had a thickened endometrium and an isolated mass in the cavity (Fig 1b). A bone scan, as well as computed tomography of the chest, were all normal; ultrasonographic examination of the abdomen showed no evidence of metastatic foci. An endometrial curettage was performed and a diagnosis of poorly differentiated carcinoma was rendered (Fig 1d). The patient underwent a total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy along with pelvic and periaortic lymphadenectomy. No gross evidence of tumor was observed in the abdominal cavity.

Figure 1.

Examination showed a mass in the uterus cavity; biopsy of the endometrium indicated poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, just like primary breast cancer.

Pathology

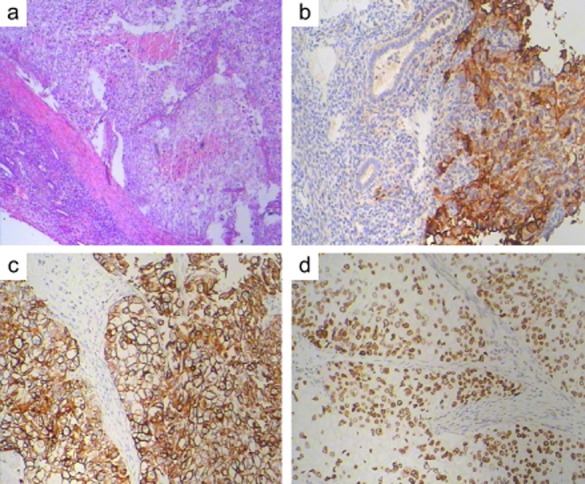

The uterus measured 7 cm × 7 cm × 5 cm. There was a mass in the uterine cavity that measured 3.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 1.5 cm. (Fig 1c), Both the fallopian tubes and the ovaries were grossly unremarkable. On microscopic examination, the malignant ductal epithelial cells were observed to have diffusely infiltrated the endometrium, sparing the endometrial glands, and they formed sheets and duct-like structures in some areas. In addition, necrosis was observed in some regions. Some tumor cells had invaded the deep muscle of the uterus (Fig 2a, hematoxylin and eosin stain, 200×), and, neoplastic emboli were present in blood vessels. There was no evidence of neoplasm in the fallopian tubes, ligaments, ovaries, periaortic or pelvic lymph nodes. The primary breast carcinoma showed a histologic appearance identical to that of the metastatic carcinoma in the endometrium. To rule out primary poorly differentiated endometrial cancer, an appropriate immunohistochemical panel was performed. The neoplastic cells showed the following staining characteristics: positive for EGFR (Fig 2b), CK7 (Fig 2c), and P53 (Fig 2d), partially positive for P63, CA-125 and CK5/6; and negative for CK20, ER, PR, Her-2-neu, P40, mammaglobin (MGB), and gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15). A diagnosis of ductal breast carcinoma with metastasis to the endometrium was then made.

Figure 2.

Pathological examination of the mass in the uterus, immunohistological staining for epidermal growth factor receptor, cytokeratin-7, and P53.

Discussion

Mazur et al. analyzed 52 cases of breast cancer metastases to the gynecologic organs, and the result indicated that the ovaries were affected in 86.5% of cases (45/52), endometrium in 3.8% (2/52), vagina in 5.8% (3/52), and the vulva and cervix in 1.9% (1/52).4 Most uterine metastases are a result of local retrograde lymphatic spread from preceding ovarian metastases, and they usually occur as a manifestation of widespread disease. When isolated uterine metastasis occurs, the spread is most likely hematogenous. It is well known that ILC has a very high risk of peritoneal and retroperitoneal metastasis. In addition, ILC more frequently spreads to gynecologic organs than IDC.2 Therefore, we speculated that all of these areas were suitable for lobular cancer cell implantation.

Metastatic breast cancer in the uterus often poses diagnostic problems for both the clinician and pathologist. To confirm a metastatic tumor, several conditions must be met. First, the morphologic features of the primary tumor should be identical to those observed in the uterus, and there should be a lack of associated precancerous changes or an in situ carcinoma in the uterine neoplasm, a permeative growth pattern within the endometrium with tumor entrapment of normal glands, and unusually prominent involvement of lymphatic or blood vessels.5 If patients are undergoing endocrine treatment with tamoxifen, drug-induced endometrial pathology should be excluded. Moreover, necessary immunohistochemical studies are required. Breast cancers are generally CK20 negative and CK7 positive,6 as demonstrated by the endometrial neoplasm in this case. The case presented here was TNBC without endocrine treatment, and tamoxifen-induced endometrial pathology was excluded.

GCDFP-15 is a marker that is highly sensitive and specific when used to assess metastases of breast origin. GCDFP-15 is significantly associated with breast cancer with a good prognosis, but has low expression (11.9%) in the basal-like subtype.7 MGB is another sensitive marker for breast carcinoma, but it has also been reported to be expressed in the female genital tract and its neoplasms, and is notably highly expressed in normal endocervical epithelium and endometrium.8 In this case, the metastases were negative for GCDFP-15 and MGB, which did not affect the final diagnosis.

Metastasis of breast IDC to the endometrium has rarely been reported in the literature. We found four cases, including the one presented here, Among these four cases, two patients were ER or PR positive, and two cases, including ours, were TNBC. Moreover, our case is a basal-like breast carcinoma. To the best of our knowledge, metastasis of basal-like breast carcinoma to the endometrium has not been previously reported.

We identified 12 cases of metastases to the endometrium from breast carcinoma from series and case reports in the literature (PubMed) between 1985 and 2014 (Table 1). A review of these data, including our case, revealed that 53.8% of cases (7/13) were lobular type, 30.7% (4/13) were invasive ductal type, 7.7% (1/13) were metaplastic type, and 7.7% (1/13) were micropapillary type; 76.9% of cases (10/13) were ER/PR positive, 15.3% (2/13) were ER and PR negative, one patient had unknown ER/PR status, and only one patient was Her-2/neu positive. We did not identify any hormonal receptor negative, Her-2/neu positive breast cancers with endometrium metastases. All of the patients except one (12/13) were over 50 years of age. Interestingly, endometrium metastases may occur not only in patients receiving tamoxifen, but also in patients undergoing aromatase inhibitor therapy. The endometrium was the only metastatic site in 30.7% of cases (4/13) and abnormal uterine bleeding was the first symptom in all these cases. This fact indicated that hormone receptor-positive invasive lobular breast cancer cells are more likely to metastasize to the endometrium than other cell types in patients over 50 years of age. The reason for this pattern is not clear.

Table 1.

Character of breast cancer metastases to the endometrium

| Author | Age | Tumor type | TNM stage | Metastases sites | Recurrence interval | Follow up | ER | PR | HER-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fumikata Hara9 | 44 | Lobular | cT3aN1M0 | Endometrium | 2.5 years | Died in 11 months | + | − | − |

| Arslan D10 | 57 | Ductal | T1bN3aM0 | Endometrium myometrium | 2 years | Alive | + | + | − |

| Karvouni E5 | 51 | Ductal | TxN1M0 | Endometrium liver, bone | 3 years | Died in 4 months | + | − | − |

| Erkanli S11 | 63 | Lobular | Unknown | Endometrium | 8 months | Alive | + | + | − |

| Scopa CD12 | 50 | Lobular | T3N3M0 | Endometrium cervix, ovary | 3 years | Died in 18 months | + | + | + |

| Scopa CD12 | 81 | Lobular | T1N3M0 | Endometrium corpus | 2 years | Died in 6 months | + | + | − |

| Sinkre P13 | 58 | Metapl astic | T2N0M0 | Endometrium corpus, ovary | 4 years | Alive 1 year | − | + | − |

| Giordano G14 | 77 | Lobular | T2N1M0 | Endometrium | 20 years | Died in 2 months | No | No | No |

| Giordano G14 | 72 | Lobular | T2N1M0 | Endometrium myometrium ovary, cervix | 6 years | Alive 4 months | + | + | No |

| Kennebeck CH15 | 71 | Ductal | T1N1M0 | Endometrium cervix | 2.5 years | Alive 10 months | − | − | − |

| Al-brahim N16 | 53 | Lobular | T2N1M0 | Endometrium | 4 years | No | + | − | No |

| Ramalingam P17 | 59 | Microp apillary | IIIA | Endometrium bladder | 2 years | Alive 3 months | + | + | No |

| Our case | 66 | Ductal | T2N0M0 | Endometrium | 11 years | Alive | − | − | − |

+: positive

−: negative

no: unclear. ER, estrogen receptor

HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

PR, progesterone receptor

TNM, tumor node metastasis.

The peak time of recurrence in these 13 cases was between two and four years. During follow-up, 23.0% of patients (3/13) died within six months. It is, therefore, important to raise awareness of this extraordinary metastasis to achieve early detection and diagnosis, and determine the best course of treatment. Because of the limited number of cases that occur and the availability of follow-up information, additional studies are needed to further our understanding of the prognosis of these patients.

Basal-like tumors account for less than 15% of all invasive breast cancers, and they usually have a high histologic grade and a relatively poor outcome.18 A large study has shown that basal-like breast cancers are more likely than other types of breast cancer to be node negative and to metastasize to the viscera (particularly to the lungs and brain), and less likely to metastasize to bone.19,20 This is the first report of basal-like carcinoma of the breast metastasis to the endometrium.

Metastatic involvement of the endometrium should be considered when vaginal bleeding or an enlarged uterus is present. Distinguishing metastatic carcinoma from primary endometrial carcinoma is important, because the treatment for these carcinomas differs. When uterine metastasis from breast carcinoma is diagnosed, patients should be treated aggressively if no other extra-genital metastatic lesions were discovered. If the disease is widespread and involves many other extra-genital sites, surgical intervention does not appear to be indicated; however, systemic chemotherapy can play an important role in these patients by improving survival and quality of life.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Piura B, Yanai-Inbar I, Rabinovich A, Zalmanov S, Goldstein J. Abnormal uterine bleeding as a presenting sign of metastases to the uterine corpus, cervix and vagina in a breast cancer patient on tamoxifen therapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;83:57–61. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamovec J, Bracko M. Metastatic pattern of infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast: an autopsy study. J Surg Oncol. 1991;48:28–33. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930480106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Bouëdec G, Kaufmann P, De Latour M, Reynaud P, Fonck Y, Dauplat J. Uterine metastases originating from breast cancer. Apropos of 12 cases. Arch Anat Cytol Pathol. 1993;41(3–4):140–144. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazur MT, Hsueh S, Gersell DJ. Metastases to the female genital tract. Analysis of 325 cases. Cancer. 1984;53:1978–1984. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840501)53:9<1978::aid-cncr2820530929>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karvouni E, Papakonstantinou K, Dimopoulou C, et al. Abnormal uterine bleeding as a presentation of metastatic breast disease in a patient with advanced breast cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:199–201. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tot T. Cytokeratins 20 and 7 as biomarkers: usefulness in discriminating primary from metastatic adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:758–763. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo MH, Huang YH, Ni YB, et al. Expression of mammaglobin and gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 in breast carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1241–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onuma K, Dabbs DJ, Bhargava R. Mammaglobin expression in the female genital tract: immunohistochemical analysis in benign and neoplastic endocervix and endometrium. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:418–425. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31815d05ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara F, Kiyoto S, Takabatake D, et al. Endometrial metastasis from breast cancer during adjuvant endocrine therapy. Case Rep Oncol. 2010;3:137–141. doi: 10.1159/000313921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arslan D, Tural D, Tatlı AM, Akar E, Uysal M, Erdoğan G. Isolated uterine metastasis of invasive ductal carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:793418. doi: 10.1155/2013/793418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erkanli S, Kayaselcuk F, Kuscu E, Bolat F, Sakalli H, Haberal A. Lobular carcinoma of the breast metastatic to the uterus in a patient under adjuvant anastrozole therapy. Breast. 2006;15:558–561. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scopa CD, Aletra C, Lifschitz-Mercer B, Czernobilsky B. Metastases of breast carcinoma to the uterus. Report of two cases, one harboring a primary endometrioid carcinoma, with review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:543–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinkre P, Milchgrub S, Miller DS, Albores-Saavedra J, Hameed A. Uterine metastasis from a heterologous metaplastic breast carcinoma simulating a primary uterine malignancy. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77:216–218. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giordano G, Gnetti L, Ricci R, Merisio C, Melpignano M. Metastatic extragenital neoplasms to the uterus: a clinicopathologic study of four cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(Suppl. 1):433–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennebeck CH, Alagoz T. Signet ring breast carcinoma metastases limited to the endometrium and cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;71:461–464. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Brahim N, Elavathil LJ. Metastatic breast lobular carcinoma to tamoxifen-associated endometrial polyp: case report and literature review. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005;9:166–168. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramalingam P, Middleton LP, Tamboli P, Troncoso P, Silva EG, Ayala AG. Invasive micropapillary carcinoma of the breast metastatic to the urinary bladder and endometrium: diagnostic pitfalls and review of the literature of tumors with micropapillary features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2003;7:112–119. doi: 10.1053/adpa.2003.50015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rakha EA, Reis-Filho JS, Ellis IO. Basal-like breast cancer: a critical review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2568–2581. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheang MC, Voduc D, Bajdik C, et al. Basal-like breast cancer defined by five biomarkers has superior prognostic value than triple-negative phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1368–1376. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dent R, Hanna WM, Trudeau M, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Pattern of metastatic spread in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:423–428. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]