Abstract

One pathological hallmark in ALS motor neurons (MNs) is axonal accumulation of damaged mitochondria. A fundamental question remains: does reduced degradation of those mitochondria by impaired autophagy-lysosomal system contribute to mitochondrial pathology? Here, we reveal MN-targeted progressive lysosomal deficits accompanied by impaired autophagic degradation beginning at asymptomatic stages in fALS-linked hSOD1G93A mice. Lysosomal deficits result in accumulation of autophagic vacuoles engulfing damaged mitochondria along MN axons. Live imaging of spinal MNs from the adult disease mice demonstrates impaired dynein-driven retrograde transport of late endosomes (LEs). Expressing dynein-adaptor snapin reverses transport defects by competing with hSOD1G93A for binding dynein, thus rescuing autophagy-lysosomal deficits, enhancing mitochondria turnover, improving MN survival, and ameliorating the disease phenotype in hSOD1G93A mice. Our study provides a new mechanistic link for hSOD1G93A-mediated impairment of LE transport to autophagy-lysosome deficits and mitochondria pathology. Understanding these early pathological events benefits development of new therapeutic interventions for fALS-linked MN degeneration.

Keywords: ALS, autophagy, axonal transport, cathepsin D, dynein, late endosome, lysosome, mitochondria, motor neurons, neurodegeneration, SOD1

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is one of the most common adult onset motor neuron (MN) degenerative disorders. About 10% of ALS cases are familial, of which over 20% are associated with dominant mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) genes (Rosen et al., 1993). Although the toxic mutant SOD1 gain-of-function is involved in the pathogenesis (Ilieva et al., 2009), multiple pathologic factors contribute to ALS-linked MN loss (Cleveland and Rothstein, 2001). However, early pathologic changes occurring in spinal MNs far before the symptomatic stage remain obscure. Transgenic mice carrying mutant human SOD1 (hSOD1), especially hSOD1G93A, are clinically and pathologically similar to human ALS patients (Gurney et al., 1994), thus serving as reliable fALS models to understand the early pathological events.

Mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired dynamics and degradation through mitophagy are associated with major neurodegenerative disorders (Chen and Chan, 2009; Sheng and Cai, 2012). Mutations in SOD1 and non-SOD1 ALS-related genes are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction (Cozzolino et al., 2013). Damaged mitochondria not only produce energy and buffer Ca2+ less efficiently than healthy ones, but also release harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) and initiate apoptotic signaling cascades (Beal, 1996). Thus, mitochondria pathology is a common state that triggers the decline of MN function and survival in ALS-linked pathogenesis. Proper clearance of those mitochondria via mitophagy in neurons may serve as an early protective mechanism limiting the leakage of deleterious mediators from damaged mitochondria.

Altered mitochondrial transport was reported in fALS-linked hSOD1G93A, TDP-43, and VAPB-P56S mice (Bilsland et al., 2010; De Vos et al., 2007; Magrané and Manfredi, 2009; Mórotz et al., 2012; Shan et al., 2010). Thus, one of current hypotheses is that the aberrant axonal accumulation of damaged mitochondria could be due to reduced mitochondrial transport. We previously tested this hypothesis by genetically crossing fALS-linked hSOD1G93A mice and syntaphilin−/− knockout mice. Syntaphilin acts as a docking receptor specifically targeting axonal mitochondria; deleting syntaphilin in mice results in the majority (~70%) of axonal mitochondria in a motile pool (Kang et al., 2008). We found that the two-fold increase in axonal mitochondrial motility in the crossed SOD1G93A/snph−/− mouse does not slow ALS-like disease progression (Zhu and Sheng, 2011). Our findings are consistent with a recent study that mitochondrial transport deficits are not sufficient to cause axon degeneration in mutant hSOD1 models (Marinkovic et al., 2012), thus challenging the hypothesis that defective mitochondrial transport contributes to rapid-onset MN degeneration. These observations raise a fundamental question: does impaired degradation of damaged mitochondria through the lysosome system play a more pathological role during the early asymptomatic stage of fALS-linked mice?

Lysosomal maturation and function in neurons depends on the proper retrograde transport of late endosomes (LEs) and endo-lysosomal membrane trafficking (Cai et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011); such transport and trafficking events are particularly challenged in spinal MNs with extended long axons. Our central hypothesis is that an imbalanced flux between autophagy or mitophagy induction and subsequent degradation within lysosomes will result in autophagic stress and mitochondrial pathology in axons, thus causing distal axons to become more vulnerable to dying-back degeneration. While the pathological roles of an impaired autophagy-lysosomal system in other neurodegenerative diseases were recently reported (Harris and Rubinsztein, 2012; Nixon, 2013), this cellular pathway was not examined in live spinal MN cultures isolated from disease-stage fALS-linked mouse models. Thus, it is very significant to investigate endolysosomal trafficking and autophagy-lysosomal maturation and degradation capacity in the context of both in vivo murine models and in vitro MNs isolated from adult mice.

In the current study, we reveal MN-targeted progressive lysosome defects in the hSOD1G93A mice starting as early as postnatal day 40 (P40), accompanied by aberrant accumulation of damaged mitochondria engulfed by autophagosomes in lumbar ventral root axons. These phenotypes were further confirmed in cultured spinal MNs, but not dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory neurons, isolated from young adult (P40) hSOD1G93A mice. Our in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrate that endo-lysosomal transport is crucial to maintain mitochondrial integrity and MN survival. Such deficits are attributable to impaired retrograde transport of late endosomes by mutant hSOD1G93A, which interferes with dynein-snapin (motoradaptor) coupling, thus reducing the recruitment of dynein motors to the organelles for transport. These deficits can be rescued by elevated snapin expression, which competes with hSOD1G93A to restore dynein-driven transport. AAV9-snapin injection in hSOD1G93A mice reverses mitochondria pathology, reduces MN loss, and ameliorates the fALS-linked disease phenotype. Our study reveals a new cellular target for development of early therapeutic intervention when MNs may still be salvageable.

RESULTS

Progressive Lysosomal Deficits in hSOD1G93A MNs Starting at Asymptomatic Stages

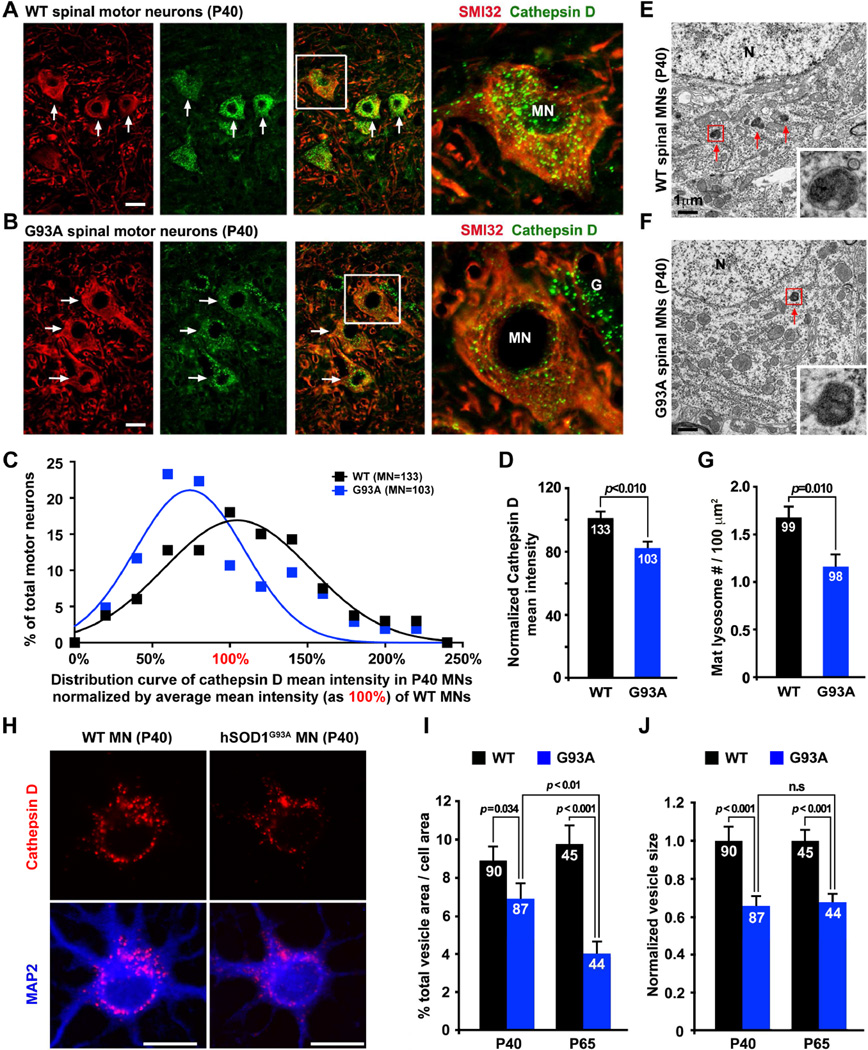

Our previous study demonstrates that the hSOD1G93A mouse strain [B6.Cg-Tg (SOD1G93As) 1Gur/J] shows no MN loss until disease onset at P123–127 and rapidly reaches disease end stage by P157±9 (Zhu and Sheng, 2011). We asked whether spinal MNs display any detectable lysosomal deficits at early asymptomatic stages. We chose a lysosome-specific marker for our study. Antibodies against cathepsin D, a lysosomal aspartic protease, and LAMP-1 were used to co-immunostain lumbar spinal cords from P40 WT mice. In SMI32-labeled spinal MNs, almost all cathepsin D signals co-localize with LAMP-1, while substantial number of LAMP-1 puncta are not labeled by cathepsin D, suggesting that cathepsin D is a reliable lysosome marker in MNs in vivo (Figure S1A). Strikingly, in P40 hSOD1G93A mice, spinal MNs show a substantially lower intensity of cathepsin D signals (Figures 1A, 1B). Quantitative analysis reveals a left-shift in the distribution of hSOD1G93A MNs to lower cathepsin D mean intensity relative to that from agematched WT littermates (Figures 1C, 1D). With transmission electron microscopy (TEM), we observed a reduced density of morphologically featured lysosomes, characterized by electrondense content, in the lumbar spinal MNs from P40 hSOD1G93A mice (1.16 ± 0.14/100 µm2, p=0.01) compared to their WT littermates (1.68 ± 0.14/100 µm2) (Figures 1E–1G). Thus, both light and electron microscopy images consistently suggest lysosomal deficits in hSOD1G93A spinal MNs at an early asymptomatic stage.

Figure 1. Reduced Lysosomal Density in Spinal MNs from Asymptomatic hSOD1G93A Mice.

(A–D) Images and quantitative analysis showing reduced lysosomal density in hSOD1G93A MNs. Lumbar spinal cords from P40 WT (A) or hSOD1G93A mice (B) were co-immunostained with MN marker SMI32 and lysosome marker cathepsin D. Arrows point to MNs. Right panels (A, B) show enlarged images from boxed MNs. Integrated intensity of cathepsin D was measured using NIH ImageJ, followed by calibration with the size of the soma and expressed as mean intensity, which was normalized by the average mean intensity in WT MNs setting as 100% (D). There is a left shift in the distribution of cathepsin D mean intensity in hSOD1G93A MNs (C). Data were collected form the total number of MNs (indicated within bars) from 6 WT and 5 hSODG93A littermates. “G”: glial cell.

(E–G) Electron micrographs (E, F) and quantitative analysis (G) showing reduced density of lysosomes with electron-dense contents (red arrows) in the spinal MNs of P40 hSOD1G93A mice. Boxed area shows enlarged images of lysosomes. Data were analyzed from the total number of micrographs (indicated within bars) taken from 3 pairs of littermates. (“N”: nucleus).

(H–J) Images (H) and quantitative analysis (I, J) showing reduced lysosomal mean intensity in cultured MNs isolated from adult (P40 and P65) hSOD1G93A mice. Neurons were co-immunostained with cathepsin D and MAP2 at DIV7.

Scale bars: 20 µm (A, B and H) and 1 µm (E and F). Data were analyzed from the total number of cultured MNs (indicated within bars) and expressed as mean ± standard error with the Student t test. (Also see Figure S1).

To characterize lysosomal maturation and autophagy degradation in live MNs, we cultured spinal MNs isolated from adult diseased mice, combined with transgene expression. These cultured adult spinal MNs can be well maintained in vitro for up to three weeks (Figures S1B, S1C). Compared to embryonic MN cultures or cell lines routinely used in the ALS field, adult MN cultures provide more reliable cell models for investigating cellular mechanisms underlying adult onset and spinal MN-targeted pathogenesis. First, we examined the relative density of cathepsin D in cultured spinal MNs at DIV7 isolated from adult (P40 or P65) WT and hSOD1G93A mice. Cultured hSOD1G93A MNs recapitulate lysosome deficits shown in spinal MN slices (Figures 1H–1J), thus establishing a live MN model for studying adult onset ALS-linked lysosome deficits.

We confirmed the lysosomal deficits in cultured adult hSOD1G93A MNs by examining mature forms of lysosomal cathepsin D and cathepsin B, which were specifically labeled by Bodipy FL-pepstatin A or the cresyl violet fluorogenic substrate CV-(Arg-Arg)2 (Magic Red), respectively. The majority of Bodipy FL-pepstatin A signals colocalize with cathepsin D in adult dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons from P80 WT mice (Figure S1D). Some cathepsin D signals have low or no staining by Bodipy FL-pepstatin A, indicating immature lysosomes. In adult MN cultures from P40 hSOD1G93A mice, normalized mean intensity of the active forms of cathepsin B and D were significantly reduced relative to that from their WT littermates (Figures S1E–S1H), which is consistent in organotypic slice cultures of spinal cords from P40 hSOD1G93A mice (data not shown), reflecting impaired lysosome maturation at such an early asymptomatic stage.

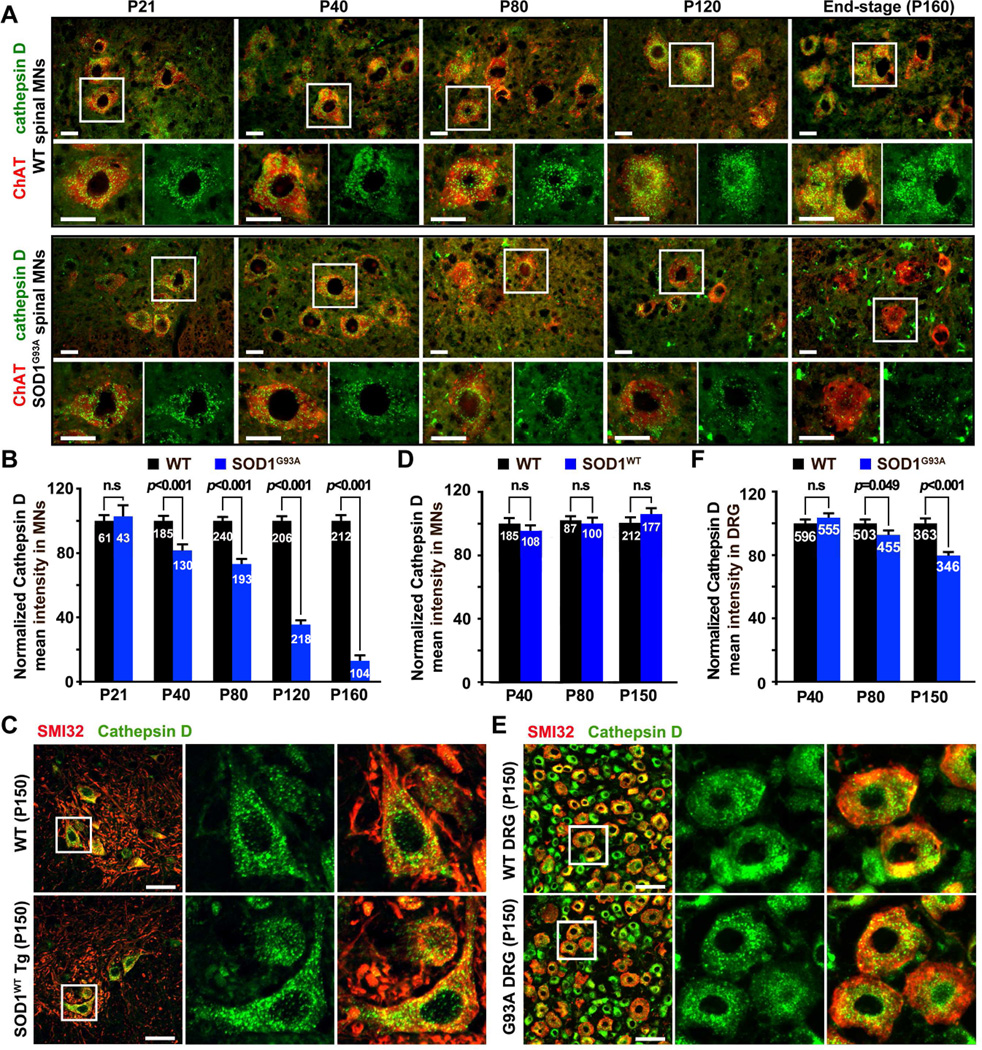

Next, we asked whether lysosome deficits become more robust with disease progression. We examined spinal MNs at various disease stages, including early asymptomatic (P21 and P40), pre-symptomatic (P80), disease onset (P120), and end-stage (P148–160). Mean intensity of cathepsin D in WT MNs is relatively stable between P21 and P40 and gradually increases after P80. Conversely, mean intensity of cathepsin D in hSOD1G93A MNs progressively decreases to 81.7 ± 3.8% (p<0.001) at P40, 73.0 ± 3.2% (p<0.001) at P80, 35.5 ± 2.6% (p<0.001) at P120, and 13.0 ± 3.5% (p<0.001) at P148–160 relative to that from agedmatched WT littermates (Figures 2A, 2B). It is notable that there are increased non-neuronal lysosomal signals at disease onset (P120) and end-stage (P148–160). This is likely attributable to glial lysosomal activation following glial proliferation (Wootz et al., 2006), which was evidenced by cathepsin D signals that are mainly localized in the GFAP-positive astrocytes or Iba1-positive microglia at the disease end-stage (Figure S2A). As a control, the transgenic mice expressing wild-type hSOD1 display no lysosomal deficits as late as P150 (Figures 2C, 2D). We also examined DRG sensory neurons from the same mutant hSOD1G93A mice. Normalized mean intensity of cathepsin D in DRG neurons is slightly reduced to 83.7 ± 1.7% of WT levels at the disease end-stage (Figures 2E, 2F), a much milder reduction compared to that found in the mutant spinal MNs. There is no statistical difference in the matured forms of cathepsin B and D between WT and mutant DRG cultures from presymptomatic (P80) hSOD1G93A mice (Figures S2B–S2E). Thus, progressive lysosome deficit is an MN-targeted pathological event beginning at early asymptomatic stages in hSOD1G93A mice.

Figure 2. Progressive Lysosomal Deficits in hSOD1G93A Spinal MNs.

(A, B) Images (A) and quantitative analysis (B) showing progressive reduction of lysosomal density in spinal MNs from early asymptomatic stage to the disease end-stage. Lumbar spinal cords were co-stained with cathepsin D and the MN marker ChAT.

(C, D) Images (C) and quantitative analysis (D) showing no reduction of cathepsin D intensity in WT hSOD1 mice at P150.

(E, F) Images (E) and quantitative analysis (F) showing a slight reduction in lysosomal density in DRG neurons at late (P150) disease stages of hSOD1G93A mice.

Scale bars: 20 µm (A, C and E). All data were expressed as mean ± standard error with the Student t test. At least 3 pairs of littermates were used for each time point and the total number of MNs for analysis is indicated within bars (B, D and F). (Also see Figure S2).

Impaired Autophagic Clearance Associates Mitochondrial Pathology in MN Axons

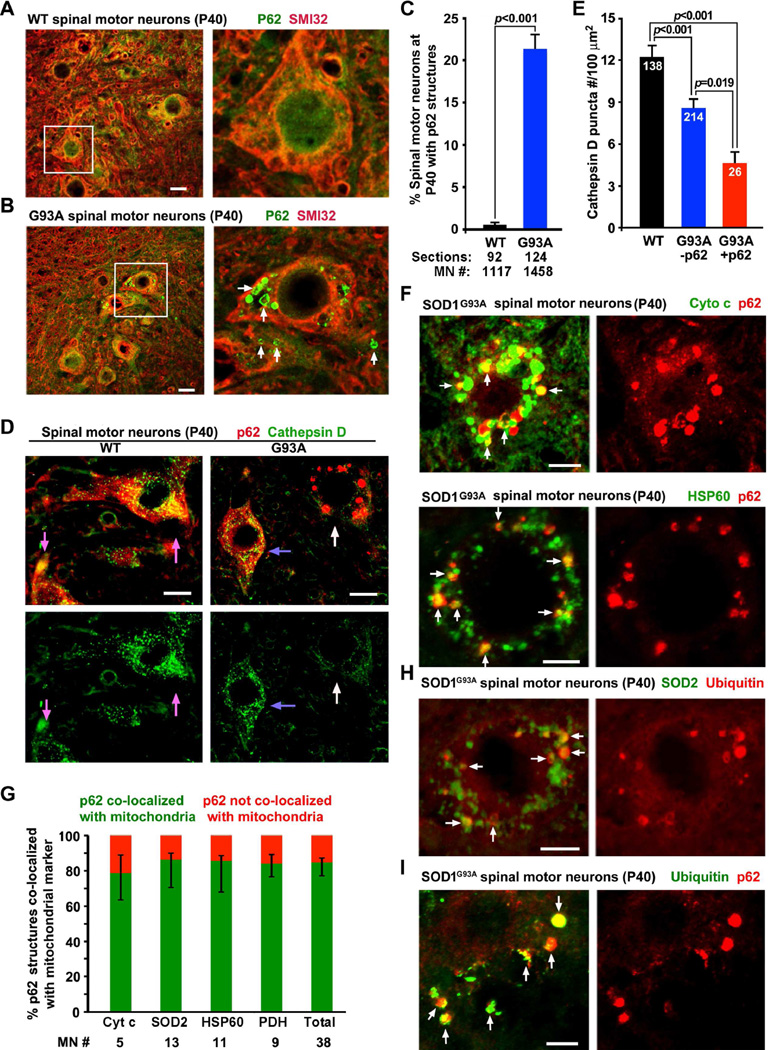

Our findings raise a question of whether robust lysosome deficits in the spinal MNs impair autophagy and mitophagy clearance. To address this issue, we examined lumbar spinal cord slice sections by co-immunostaining SMI32 and the autophagy marker p62. The p62 ring-like structures were accumulated in a population (21.35 ± 1.76%) of MNs from P40 hSOD1G93A mice (Figures 3A–3C), but were rarely found in MNs from WT littermates (0.57 ± 0.26%, p<0.001). This phenotype is reproduced in cultured spinal MNs at DIV7 from P40 hSOD1G93A mice (Figures S3A, S3B). Interestingly, MNs with large clustered p62 structures showed a more robust reduction in cathepsin D density relative to that from the mutant MNs with no detectable p62 puncta (p=0.019) or from WT MNs (p<0.001) (Figures 3D, 3E). Thus, the extent of lysosome deficits correlates with levels of accumulated autophagic vacuoles (AVs). The majority (85.28%) of p62-labeled vacuoles in the mutant MNs colocalized with various mitochondrial markers (Figure 3G), including cytochrome c (Cyto c), heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) (Figure 3F), superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), or pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) (Figures S3C, S3D), representing mitophagic intermediates engulfing damaged mitochondria. Some of which show ubiquitination (Figures 3H, 3I). Aberrant clustering of P62-labeled mitochondria in hSOD1G93A MNs supports our hypothesis that lysosomal deficits impair degradation of damaged mitochondria.

Figure 3. Lysosome Deficits Associate with Accumulated AVs in Spinal MNs from Early Asymptomatic hSOD1G93A Mice.

(A–C) Images (A, B) and quantitative analysis (C) showing p62 ring-like AVs (arrows) in a population (21.35 ± 1.76%) of hSOD1G93A spinal MNs. P40 lumbar spinal cord slices were co-stained with SMI32 and p62. The right panels show enlarged views of the boxed MNs. Data were analyzed from a large number of MNs (n>1000) from the total number of slice sections (indicated below bars) taken from 19 WT and 14 hSOD1G93A mice.

(D, E) Images (D) and quantitative analysis (E) showing the correlation of reduced cathepsin D density and accumulated p62 structures (white arrows) in P40 hSOD1G93A MNs. Blue arrows point to mutant MNs with high cathepsin D density but no detectable large p62 structures. Pink arrows indicate WT neurons. Data were analyzed from the total number of MNs indicated within bars (E), taken from 4 pairs of littermates.

(F, G) Images (F) and quantitative analysis (G) showing the co-localization of the majority of p62 structures (85.28%) with mitochondrial markers cytochrome c (Cyto c) or heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) in spinal MNs from P40 hSOD1G93A mice. (Also see Figure S3).

(H, I) Representative images showing ubiquitination of p62-targeted mitochondria in the spinal MNs from P40 hSOD1G93A mice

Scale bars: 20 µm (A, B, D, F and H) and 10 µm (I), respectively. Data were expressed as mean ± standard error with the Student t test.

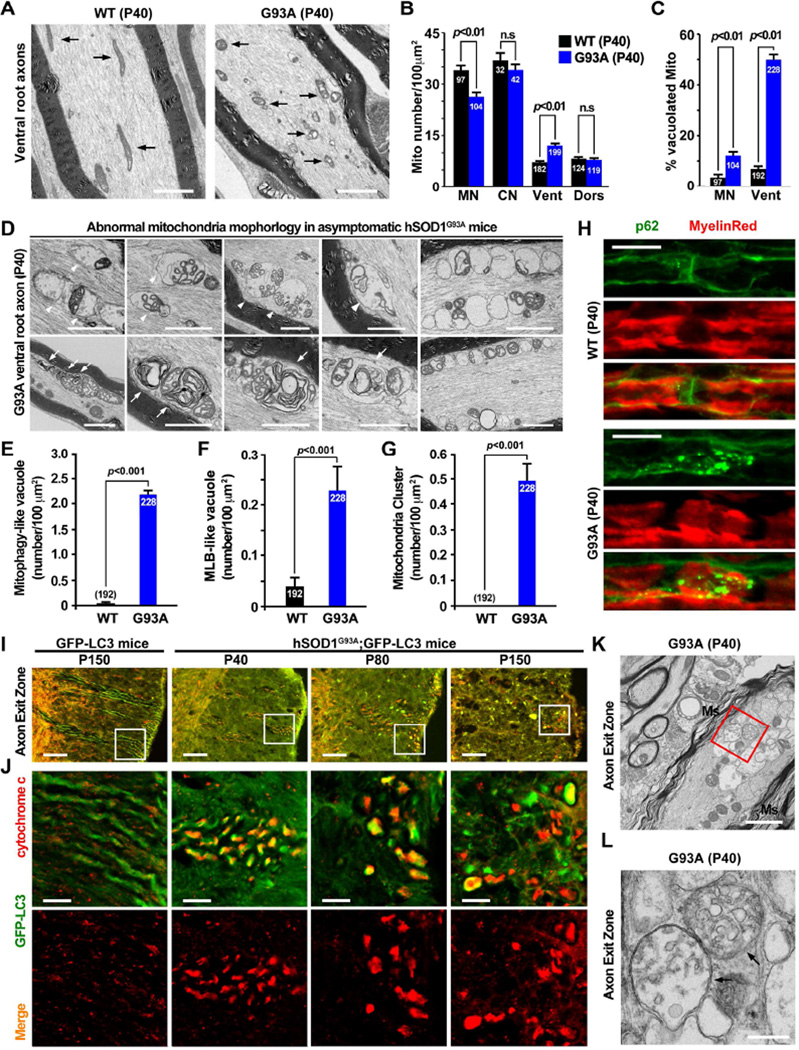

We examined mitochondrial ultra-structures in lumbar spinal cords and ventral root axons. Although swollen and vacuolated mitochondria are observed in hSOD1G93A MN soma (Figure S4A), mitochondria in ventral root axons displayed more robust degenerative phenotypes including fragmentation, cristae distortions, vacuolization, or swelling and clustering (Figures 4A, 4D). These phenotypes were readily detectable as early as in P40 hSOD1G93A mice but rarely found in WT littermates. Quantitative analysis revealed reduced mitochondria density in the soma of spinal MNs and relatively increased density in the ventral root axons (p<0.01) (Figure 4B). No significant change was observed in mitochondria density in cortical MNs and dorsal root axons between P40 WT and hSOD1G93A littermates. Only mild mitochondria vacuolization was seen in mutant dorsal root axons (Figure S4A). Vacuolated mitochondria in ventral root axons appear more robust (49.90 ± 2.07%) when compared to the soma of MNs (12.12 ± 0.94%) from the same P40 hSOD1G93A mice (Figures 4C, 4D). Mitochondrial clustering was further confirmed in ventral root slice sections by staining axonal mitochondrial marker syntaphilin (Figure S4B).

Figure 4. Mitochondria Pathology in the Ventral Root Axons of Early Asymptomatic hSOD1G93A Mice.

(A–C) Electron micrographs and quantification showing fragmented, vacuolated and clustered mitochondria (A), increased mitochondrial density (B) and robustly increased vacuolated mitochondria (C) in the ventral root axons (Vent) of early asymptomatic hSOD1G93A.

(D–G) Electron micrographs (D) and quantification (E–G) showing accumulation of AVs engulfing damaged mitochondria (arrowheads) and multilamellar bodies (MLB, arrows) in lumbar ventral root axons from P40 hSOD1G93A mice. Note that clustered mitochondria (right panels) were found at this early age.

(H) Clustering of p62 AVs in ventral root axons from P40 hSOD1G93A mice. Axon myelin sheaths are outlined with MyelinRed.

(I, J) Aberrant accumulation of LC3-labeled AVs engulfing fragmented mitochondria (cytochrome c) in axon exit zones of crossed GFP-LC3 / hSOD1G93A mice at P40, P80 and P150 stages. Panels in (J) are zoomed images of the boxed area in (I).

(K, L) Electron micrographs showing clustered AVs (arrows) engulfing organelles in the axon exit zone of P40 hSOD1G93A mice. The red box was enlarged in L. Ms: myelin sheath.

Data were analyzed from a total number of micrographs indicated within bars (B, C, E and F) and expressed as mean ± standard error with the Student t test. Scale bars: 2 µm (A, D, K), 20 µm (H, I), 5 µm (J) or 500 nm (L). (Also see Figure S4).

In addition to altered mitochondria ultrastructure, we observed more striking axonal phenotypes in hSOD1G93A mice: aberrant accumulation and clustering of multilamellar bodies (MLBs), and amphisome-like structures engulfing damaged mitochondria with collapsed cristae (Figures 4D–4G). These unique structures were readily found in ventral root axons of P40 hSOD1G93A mice, but are almost absent in age-matched WT mice. MLBs are altered autolysosomes containing multiple concentric membrane layers and are associated with various lysosomal storage diseases (Hariri et al., 2000), while amphisomes are intermediate AVs originating from the fusion between late endocytic vacuoles and autophagosomes (Cheng et al., 2015). These MLBs and amphisomes were also enriched in cortical neurons by inhibiting lysosomal cathepsin D proteolysis (Boland et al., 2008). Furthermore, we crossed the GFP-LC3 transgenic mouse (Mizushima et al., 2004) with the hSOD1G93A mouse. Co-localization of mitochondria and GFP-LC3-labeled AVs was readily detectable within axon exit zones in the crossed mice (Figures 4I, 4J). TEM analysis confirmed that double-membrane AV-like structures engulfing damaged mitochondria and other degradative materials were clustered within the axon exit zones (Figures 4K, 4L). Consistently, p62-labeled AVs were clustered along ventral root axons of P40 hSOD1G93A mice but rarely in the age-matched WT (Figure 4H). Thus, our study suggests impaired autophagy-mitophagy degradation in MN axons of hSOD1G93A mice at early asymptomatic stages.

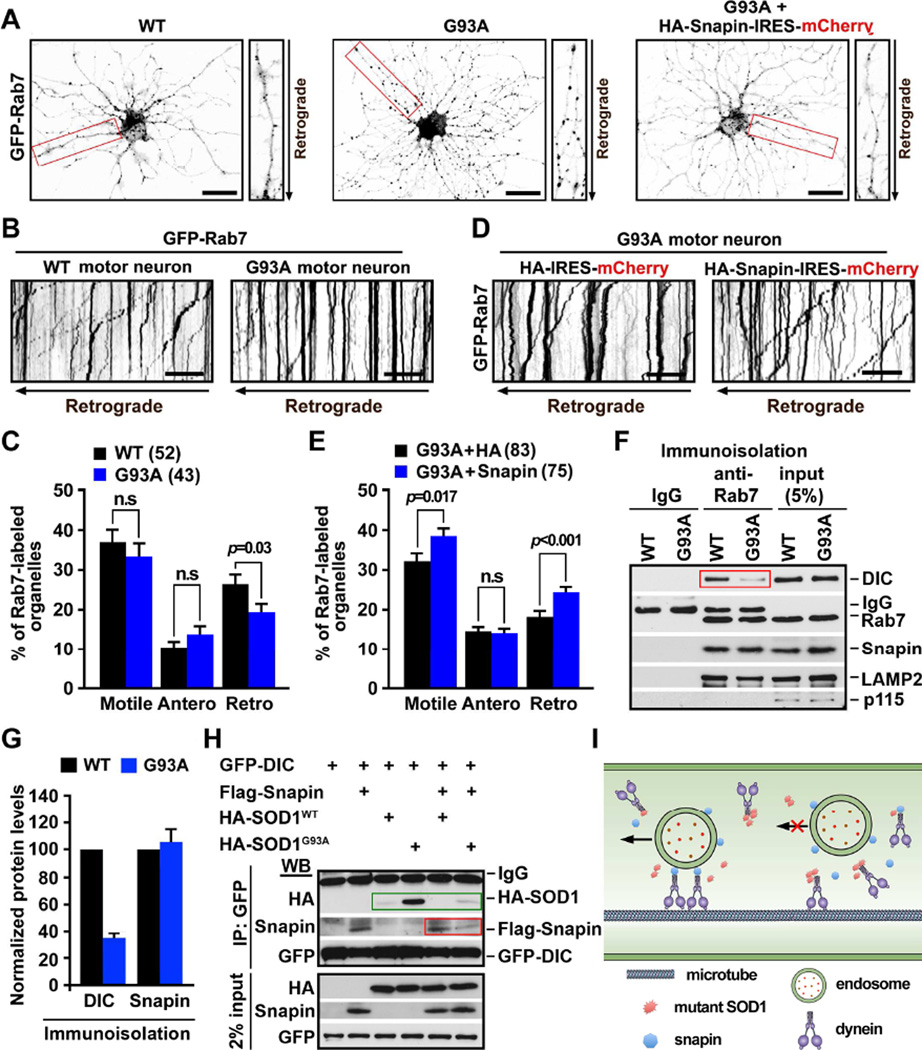

Snapin Rescues LE Retrograde Transport by Competing with hSOD1G93A for Binding to Dynein

Lysosomal maturation in neurons depends on the proper LE retrograde transport and endolysosomal trafficking (Cai et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011), which is driven by dynein motors from distal processes to the soma. Our findings raise the question of whether lysosome deficits in hSOD1G93A MNs reflect altered endolysosome trafficking. To address this issue, we took advantage of live spinal MN cultures from P40 mice to examine axonal transport of late endocytic organelles labeled with GFP-Rab7 (see Experimental Procedures). In WT MNs, LEs appeared as small fine vesicular structures evenly distributed along processes. In contrast, they were clustered in larger puncta in processes of mutant MNs (Figure 5A). Time-lapse imaging showed predominant retrograde transport of LEs along processes toward the soma in WT MNs (Figures 5B, 5C). However, hSOD1G93A MNs displayed reduced retrograde transport (p=0.03), while there was no significant change in anterograde transport (p>0.05).

Figure 5. Snapin Rescues LE Retrograde Transport by Competing with hSOD1G93A for Binding to Dynein.

(A) Images showing distribution of Rab7-labeled organelles in adult spinal MNs from P40 WT or hSOD1G93A mice. Note that LEs in the mutant MNs appeared as large clusters along processes. Transient snapin overexpression reversed the mutant phenotype (right). Neurites in red boxes were zoomed on the right side.

(B, C) Kymographs (B) and quantitative analysis (C) showing reduced LEs retrograde transport in P40 hSOD1G93A MNs. Time-lapse imaging was recorded at DIV7 for 100 frames with 2.5-sec intervals. In kymographs, vertical lines represent stationary organelles; oblique lines or curves to the left indicate retrograde transport.

(D, E) Kymographs (D) and quantitative analysis (E) showing enhanced LE retrograde transport by expressing snapin transgene in hSOD1G93A MNs. Motility was quantified from a total number of neurites as indicated in parentheses from 3 experiments and expressed as mean ± standard error with Student t test. Scale bars: 20 µm (A, B, D).

(F, G) Immuno-isolation (F) and quantitative analysis (G) showing reduced association of DIC with LEs in hSOD1G93A mouse spinal cords. Data were analyzed from three repeats and expressed as mean ± standard error.

(H) Immunoprecipitation showing competitive binding of snapin and hSOD1G93A with DIC. Note that snapin inhibits the hSOD1G93A-DIC coupling (green box), while hSOD1G93A but not hSOD1wt reduced the snapin-DIC coupling (red box).

(I) Proposed model: Snapin serves as an adaptor attaching dynein to LEs through binding to DIC (left). In hSOD1G93A MNs, The snapin-DIC coupling is blocked by hSODG93A-DIC interaction (right), thus impairing LE retrograde transport. Elevated snapin expression reverses the mutant phenotype by competing with hSOD1G93A for binding DIC. (Also see Figure S5).

Snapin acts as an adaptor recruiting dynein motors to late endosomes via binding to the dynein intermediate chain (DIC), thus coordinating dynein-driven retrograde transport and endolysosomal trafficking (Cai et al., 2010). LE-loaded dynein-snapin complexes drive AV retrograde transport after they fuse into amphisomes (Cheng et al., 2015). These mechanisms enable neurons to maintain efficient degradation capacity. To rescue lysosome deficits and mitochondrial pathology, we introduced the snapin transgene into mutant hSOD1G93A MNs through lentivirus infection. Elevated snapin expression enhanced retrograde (p<0.001) but not anterograde transport of LEs (Figures 5D, 5E) and reduced their clustering in the processes of mutant MNs (Figure 5A). As a control, expressing the snapin-L99K mutant defective in DIC binding failed to rescue the retrograde transport (Figures S5A, S5B), further confirming the role of snapin-DIC coupling in driving LE transport.

It was reported that mutant hSOD1G93A, but not WT hSOD1, interacts with the dynein DIC (Zhang et al., 2007). This raises the question if the mutant hSOD1 competes with snapin for binding DIC, thus interfering with the snapin-DIC coupling in recruiting dynein to LEs for retrograde transport (Figure 5I)? To address this question, we immuno-isolated late endocytic organelles from spinal cords with Dynal magnetic beads coated with an anti-Rab7 antibody. Association of DIC with Rab7-labeled organelles was reduced to 34% in P40 hSOD1G93A mice compared to that from age-matched WT mice (p<0.001) (Figures 5F, 5G). This reduced DIC tethering to Rab7-labeled organelles was not observed in hSOD1wt transgenic mice (Figures S5C, S5D). We further showed that DIC selectively binds to hSOD1G93A but not hSOD1wt (Figure 5H). While snapin binds to DIC but not to hSOD1WT and hSOD1G93A under the same conditions (Figure S5E), over-expressing snapin inhibits hSOD1G93A-DIC coupling (Figure 5H). These data support our hypothesis that retrograde transport of LEs is impaired by hSOD1G93A-DIC interaction which interferes with the snapin-DIC complex, thereby reducing dynein recruitment to LEs for transport (Figures 5F, 5I). By competitively binding to DIC, hSOD1G93A and snapin play opposite roles in dynein-driven LE retrograde transport.

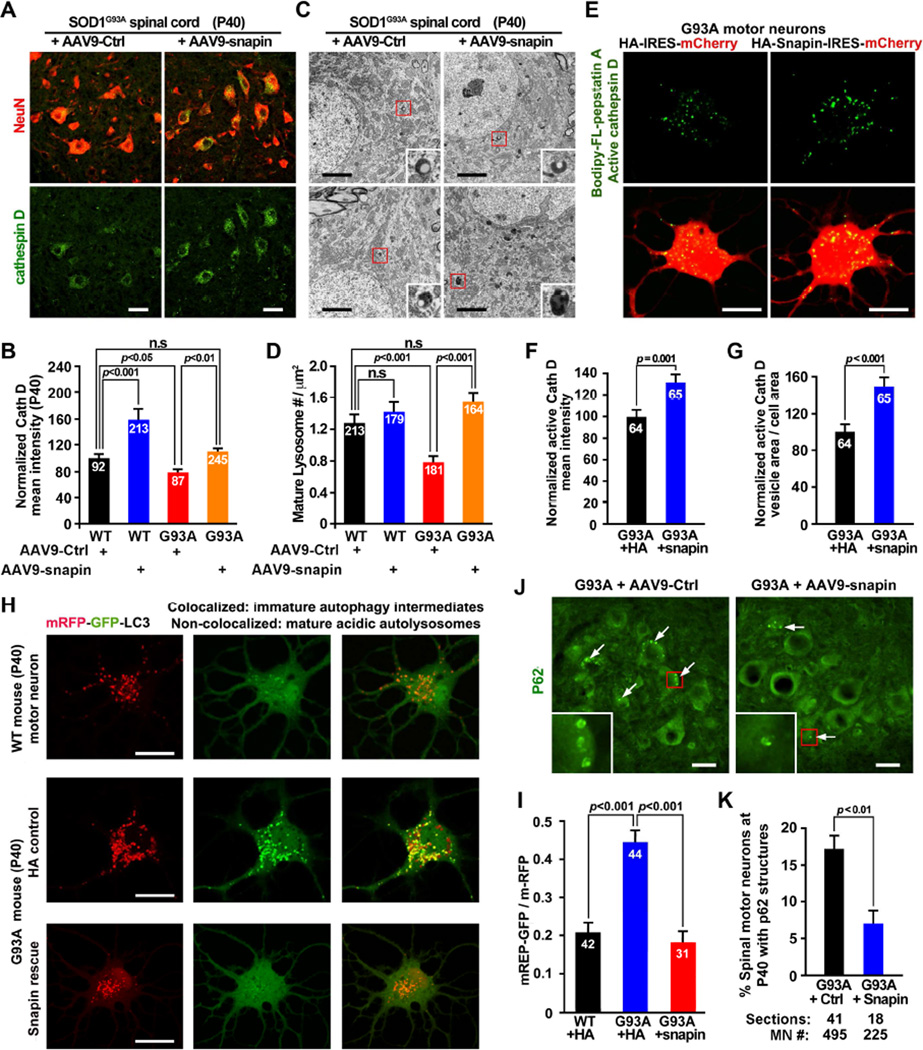

Impaired Retrograde Transport Underlying Lysosomal Deficits

We thought to ask whether enhancing retrograde transport by snapin could rescue autophagylysosomal deficits in vivo and in vitro. First, we over-expressed snapin in the spinal cord of hSOD1G93A mice by injecting AAV9-mChery-IRES-snapin into P0 mice through temporal vein, an established in vivo MN gene delivery procedure (Foust et al., 2010). The majority (>96%) of SMI32- or NeuN-labeled spinal MNs in P40 mice were infected (Figures S6A–S6D). There is a significant increase in cathepsin D mean intensity in both WT and hSOD1G93A spinal MNs of P40 mice after in vivo snapin overexpression (Figures 6A, 6B). Consistently, quantitative analysis of TEM micrographs (>164 for each) revealed an increased density of morphologically featured lysosomes in hSOD1G93A spinal cords following in vivo snapin overexpression (Figures 6C, 6D). In addition, transient HA-snapin expression in cultured P40 hSOD1G93A MNs significantly increased mean intensity (31.59%, p=0.001) and density (47.11%, p<0.001) of Bodipy FL-pepstatin A-labeled mature lysosomes relative to that from the same mutant MNs expressing HA control (Figures 6E–6G).

Figure 6. Enhancing Retrograde Transport by Snapin Rescues Autophagy-Lysosomal Deficits.

(A, B) Images (A) and quantitative analysis (B) showing rescued lysosomal deficits in hSOD1G93A MNs following AAV9-snapin infection. Lumbar spinal cords from P40 mice were coimmunostained with NeuN and cathepsin D.

(C, D) Electron micrographs (C) and quantitative analysis (D) showing increased density of lysosomes with electron-dense content in the spinal MNs of P40 hSOD1G93A mice after snapin overexpression. Boxed area show enlarged images of lysosomes.

(E–G) Images (E) and quantitative analysis (F, G) showing increased intensity and density of active cathepsin D labeled by BODIPY FL-Pepstatin A following snapin transient expression in adult MN cultures of P40 hSOD1G93A mice.

(H, I) Images (H) and quantitative analysis (I) showing that snapin rescued autophagy flux in adult hSOD1G93A MNs. MNs were co-infected with Lenti-mRFP-GFP-LC3 and HA-snapin or HA control virus. GFP, but not mRFP, was rapidly degraded in mature acidic lysosomes. Mander’s coefficient reflects the relative ratio of co-localization between mRFP and GFP signals (I).

(J, K) Images (J) and quantitative analysis (K) showing reduced P62 autophagic structures in the spinal MNs of P40 hSOD1G93A mice following AAV9-snapin infection. Boxed area show enlarged images of P62 ring-like structures.

Data were analyzed from the total number of MNs (B, F, G, I and K) or micrographs (D) (indicated within bars) taken from 3 pairs of mice (D) or in 3 independent experiments, and expressed as mean ± standard error with the Student t test. Scale bars: 20 µm (A, E, H and J) or 2 µm (C). (Also see Figure S6).

Next, we asked whether rescuing lysosomal deficits by expressing snapin in MNs is sufficient to enhance autophagic degradation capacity. First, we infected cultured adult MNs with Lenti-mRFP-GFP-LC3, a chimeric LC3 autophagy reporter tagged to both GFP (acid-sensitive) and mRFP (acid-stable), followed by live imaging GFP versus mRFP signals. An autophagosome acquires acidic properties when it matures into an autolysosome. In WT neurons, GFP, but not mRFP, was rapidly degraded in mature acidic autolysosomes (Figure 6H, upper panels). In contrast, lysosomal deficits in hSOD1G93A MNs resulted in accumulation of immature AVs, within which both GFP and mRFP signals were retained (Figure 6H, middle panels). Mander’s coefficient analysis showed an enhanced co-localization ratio of mRFP and GFP signals in the mutant MNs from early asymptomatic mice (P40) (Figure 6I), indicating an impaired autophagic maturation or clearance. Snapin expression fully reversed the mutant phenotype: GFP underwent rapid degradation (Figures 6H, lower panels). Second, we examined p62-labeled AVs in the infected spinal cords of P40 hSOD1G93A mice. Elevated snapin expression significantly reduced the percentage of MNs displaying AV-like structures (Figures 6J, 6K). The rescued phenotype was further confirmed in cultured mutant MNs (Figures S6E, S6F), indicating enhanced autophagic cleavage following snapin over-expression. To provide a mechanistic link between rescued lysosomal deficits and enhanced dynein-driven LE retrograde transport, we expressed snapin-L99K mutant defective in dynein DIC binding in P40 hSOD1G93A MNs. In contrast to effective rescue capacity by expressing WT snapin, expressing snapin-L99K mutant failed to enhance active cathepsin D levels (Figures S6G, S6H); failed to reduce p62-labled AVs (Figure S6I); and further impaired degradation of GFP in adult hSOD1G93A MNs (Figure S6J). Thus, early deficits in autophagy-lysosomal function in hSOD1G93A MNs can be effectively rescued by snapin expression both in vitro and in vivo. Elevated snapin competes with hSOD1G93A for binding to dynein motors, thereby enhancing endolysosomal trafficking and maturation.

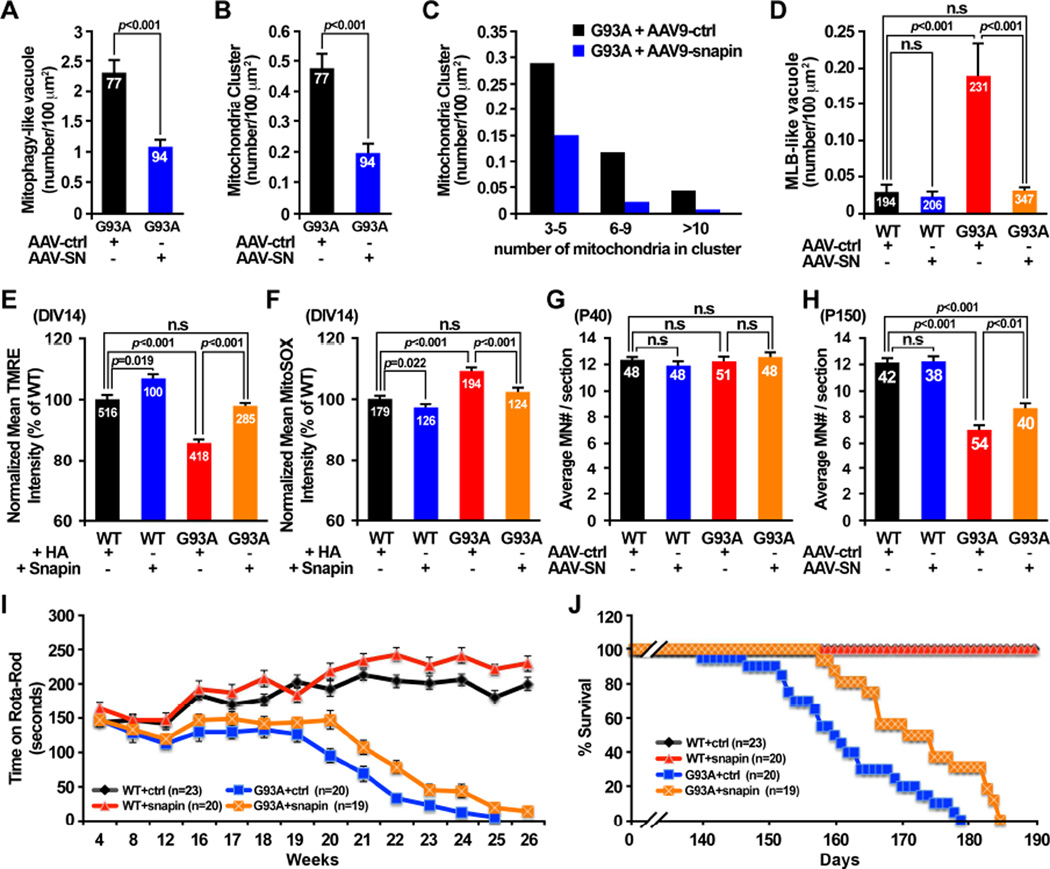

Enhanced Retrograde Transport Reverses Mitochondria Pathology and Reduces Disease Progression in hSOD1G93A mice

Sequestration of damaged mitochondria into autophagosomes and subsequent degradation within lysosomes constitute a key cellular pathway in maintaining mitochondrial quality. We proposed that snapin-mediated enhancement of autophagy-lysosomal function in hSOD1G93A MNs facilitates removal of damaged mitochondria. To test our hypothesis, we examined mitochondrial ultrastructure in ventral root axons from P40 WT and hSOD1G93A mice injected with AAV9-snapin or AAV9 control vector. Robust mitochondrial degeneration including fragmentation, cristae distortions, vacuolization, swelling and clustering observed in P40 hSOD1G93A mice (Figures 4A, 4D) were significantly reduced following injection with AAV9-snapin, but still remained in mutant mice injected with control AAV9 vector (Figures 7A–7C). In addition, snapin over-expression dramatically reduced the number of MLBs in hSOD1G93A mice axons (Figure 7D). Since those MLBs are likely originated from degenerative mitochondria (Figure 4D), these in vivo rescue effects support our notion that elevated snapin expression plays a crucial role in reducing mitochondrial pathology by removing damaged mitochondria in the diseased MN axons.

Figure 7. Snapin Reduces Mitochondrial Pathology and Disease Progression.

(A–D) AAV9-snapin infection in hSOD1G93A mouse spinal cords significantly reduced the density of degenerated mitochondria with >50% loss of cristae (A), removed clusters of damaged mitochondria (B, C), and facilitated clearance of multilamellar bodies (D).

(E) Elevated snapin expression reversed depolarized (ΔψS) axonal mitochondria phenotype in the mutant MNs. MNs at DIV1 were infected with pLenti-Snapin-IRES-GFP or pLenti-HA-IRES-GFP control, followed by loading (50 nM, 15 min) of Δψm-dependent fluorescent dye TMRE at DIV14.

(F) Elevated snapin expression reduced mitochondrial oxidative stress in the mutant MNs. Note that axonal mitochondria in hSOD1G93A MNs displayed elevated superoxide fluorescence, which was reversed by snapin over-expression.

(G, H) In vivo snapin expression significant increased MN survival in hSOD1G93A mice at disease end-stage.

(I) Rota-rod tests detected increased time remained on rota-rod in hSOD1G93A mice injected with AAV9-snapin. Each mouse was placed on a accelerate rod with speed from 5 rpm to 40 rpm over 3 min. The latency to fall off the rota-rod was recorded.

(J) Elevated in vivo snapin expression extended the life span of hSOD1G93A mice. Note that death initiation in hSOD1G93A mice was postponed from P140 in AAV9 control group to P158 in AAV9-snapin group. The average lifespan of hSOD1G93A mice increased to 173±10 days with AAV9-snapin injection, compared to 161±11 days in AAV9 control group.

Data were analyzed from a total number of micrographs (A–D), MNs (E, F) or spinal cord slices (G, H) indicated within bars in 3–6 independent experiments. Animal numbers are indicated within figures (I, J). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error with Student t test. (Also see Figure S7).

We further examined axonal mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) and free radical generation, two parameters widely used to assess mitochondrial integrity. First, by loading live MNs at DIV14 with the fluorescent dye TMRE, which stains mitochondria depending upon Δψm, we found a significant decrease (p<0.001) in TMRE mean intensity in axonal mitochondria from adult hSOD1G93A MNs compared to those from age-matched WT MNs (Figure 7E), indicating mitochondrial depolarization. Transient snapin expression restored mitochondrial Δψm. Second, we examined superoxide levels in axonal mitochondria with MitoSOX Red, a mitochondrion-specific superoxide indicator. Parallel imaging of superoxide levels demonstrated elevated ROS production (p<0.001) in axonal mitochondria from P40 hSOD1G93A MNs relative to WT MNs, a phenotype that can be suppressed by snapin over-expression (Figure 7F). These two experiments further support our hypothesis: enhancing autophagy-lysosomal activity by expressing snapin removes damaged mitochondria from axons.

We conducted three lines of in vivo and in vitro experiments to examine whether expressing snapin has any beneficial impact on MN survival and disease progression in hSOD1G93A mice, First, we examined MN loss in lumbar spinal cords following viral injection. At the early asymptomatic age (P40), no significant difference was detected in the spinal cord MN counts between WT and hSOD1G93A mice (p>0.05) (Figure 7G). When animals reached the disease end stage (P150), there was a significant reduction in MN number in hSOD1G93A mice injected with the AAV9 control vector (p<0.001) compared with aged-matched WT mice (Figure 7H). However, such MN loss was reduced following in vivo snapin overexpression in spinal cords (p<0.01). Next, we examined MN survival by performing TUNEL assays (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeling). In cultured P40 hSOD1G93A MNs at DIV14, 15.83% of MNs are TUNEL positive, higher than age-matched WT MNs (p<0.05)(Figure S7A). Snapin over-expression reduced the apoptosis rate to 6.51% (p<0.01). Consistently, P40 hSOD1G93A MN cultures showed reduced survival rates relative to age-matched WT MNs; snapin over-expression increased survival over time. At DIV14, hSOD1G93A MNs expressing HA control displayed lower survival rate (36.18 ± 5.54%). However, snapin over-expression significantly enhanced survival of the diseased MNs (75.97±10.22%, p<0.001) (Figure S7B). Expressing snapin-L99K, a snapin mutant defective in dynein DIC binding, had no beneficial impact on MN survival (39.48 ± 4.79%, p=0.66) (Figure S7C). In contrast, this mutant reduces WT MN survival, likely through its dominant-negative effect on endogenous snapin.

We evaluated ALS-like disease onset and progression in hSOD1G93A mice following AAV9-snapin injection. We weighed the animals and tested motor coordination monthly during the first 3 months of age and then weekly after that. While WT mice continue to grow with age, snapin overexpression slightly reduced body weight in both female (~5%) and male (~10%) WT mice at 26 weeks old (Figures S7D, S7E). However, both male and female hSOD1G93A mice began to lose weight at age 17–18 weeks, such weight loss were not affected by snapin overexpression. Rota-rod tests detected increased time remained on rota-rod in hSOD1G93A mice injected with AAV9-snapin, indicating improved motor coordination (Figure 7I). Notably, the initiation of death in hSOD1G93A mice was postponed from P140 in control group to P158 in AAV9-snapin group. The average lifespan of hSOD1G93A mice increased to 173±10 days with AAV9-snapin injection, compared to 161±11 days in AAV9-control group (Figure 7J). WT mice with AAV9-snapin injection stayed alive throughout the duration of the experiment. Overall, reversing lysosomal deficits in hSOD1G93A mice by in vivo snapin over-expression in spinal cords reduces disease progression.

Discussion

In the current study, we reveal for the first time spinal MN-targeted progressive lysosomal deficits starting as early as at P40 asymptomatic stages in fALS-linked hSOD1G93A mice. These deficits impair autophagic/mitophagic degradation, thus resulting in aberrant accumulation of AVs engulfing damaged mitochondria along ventral root axons. These pathological phenotypes were captured in cultured adult (P40) spinal MNs but not in DRG sensory neurons from the same hSOD1G93A mice. Such early deficits are due to reduced LE retrograde transport via competitive binding of hSOD1G93A to dynein DIC, and can be reversed by introducing snapin transgene in MNs. Snapin competes with hSOD1G93A for binding to dynein DIC, thereby recruiting dynein to LEs for retrograde transport. Thus, snapin and hSOD1G93A play opposite roles in LE retrograde transport. Furthermore, we show that expressing snapin efficiently reverses autophagy-lysosome deficits and facilitates removal of damaged mitochondria, thereby prolonging mutant MN survival. Injecting AAV9-snapin into the diseased mice rescues lysosome deficits in MNs in vivo and slows MN degeneration and disease progression. Thus, our study advances our understanding of early pathological mechanisms underlying MN degeneration and also provides new mechanistic insights into how: (1) mutant hSOD1 impairs LE retrograde transport by interfering with motor-adaptor coupling, thus reducing dynein-cargo attachment; and (2) elevated snapin expression reverses the mutant phenotypes by competing with hSOD1G93A for dynein-driven retrograde transport (Figure 5I).

Lysosomal Deficit Is an Early Pathological Phenotype in hSOD1G93A Mouse MNs

We reveal progressive lysosome deficits in hSOD1G93A spinal MNs with disease progression. There are three notable features in our observations: First, lysosomal deficits are MN-targeted. Second, lysosome deficits can be detected in mutant MNs from as early as P40 asymptomatic hSOD1G93A mice, and become progressively worse after disease onset at P120 when MN loss was reported in hSOD1G93A mice (Lambrechts et al., 2003). Third, these lysosomal deficits were not observed in WT hSOD1 transgenic mice even as late as P150. These restricted and progressive changes highlight a mechanical link between lysosome deficits and fALS-linked pathogenesis in spinal MNs. The increased cathepsin D signals restricted in glial cells after disease onset in hSOD1G93A mice (Figures 2A, S2A) may reflect lysosomal activation following glial cell proliferation in the spinal cords.

Lysosome Deficits Augment Mitochondria Pathology

Autophagic flux is the equilibrium balance between autophagic formation and clearance. Since neurons are particularly sensitive to the accumulation of misfolded proteins and damaged organelles, newly formed autophagosomes are eliminated quickly by fusing with endolysosomes, thereby avoiding a buildup of AVs (Maday et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2015). However, AVs accumulate rapidly in neurons when lysosomal proteolysis is inhibited (Lee et al., 2011). Impaired autophagy clearance was also reported in various lysosomal storage disorders (Kiselyov et al., 2007; Settembre et al., 2007). Accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria is associated with a primary lysosomal defect in a mouse model of neuropathic Gaucher disease, the inherited lysosomal storage disorders (Osellame and Duchen, 2014). Thus, an imbalanced autophagic flux between enhanced autophagy/mitophagic induction and reduced clearance due to lysosomal deficits results in autophagic stress characterized by accumulated AVs engulfing protein aggregates and damaged organelles such as mitochondria.

Altered autophagy was reported in fALS-linked mouse models. Autophagy receptor p62 co-localizes with hSOD1G93A in fALS mouse spinal MNs (Gal et al., 2007) and interacts with mutant hSOD1G93A but not WT hSOD1WT. Over-expressing p62 facilitates engulfing hSOD1G93A aggregates into autophagosomes for degradation. This is consistent with our findings showing the p62 ring-like structures accumulated in MNs from P40 hSOD1G93A mice (Figures 3A–3C). Interestingly, MNs with large p62 structures showed more robust lysosome deficits (Figures 3D, 3E), thus impairing AV clearance. Our study suggests that early lysosome deficits in hSOD1G93A MNs lead to autophagy defects. Because mitochondrial pathology is a robust hallmark in fALS-linked MNs at asymptomatic stages, we assessed snapin rescue effects in both in vitro and in vivo hSOD1G93A mouse model by focusing on mitochondrial pathology phenotypes including ultrastructural changes, mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), and free radical generation.

Although increased numbers of autophagosomes were observed in the spinal cords of sALS patients and hSOD1G93A mouse during late disease stages (Li et al., 2008; Morimoto et al., 2007), the contribution of altered autophagy to the fALS-linked pathogenesis has been a subject for debate. It remains unclear whether enhanced induction of autophagy helps remove of toxic mutant protein aggregates or instead facilitates MN degeneration. In vivo treatment of hSOD1G93A mice with rapamycin, an autophagy inducer via the mTOR signaling pathway, augmented MN degeneration and disease progression and failed to reduce mutant hSOD1 aggregates in the spinal cords (Zhang et al., 2011). However, inducing mTOR-independent autophagy in hSOD1G93A mice prolonged their lifespan and attenuated the progression of disease phenotypes (Castillo et al., 2013). Studies using lithium, an mTOR-independent autophagic inducer (Sarkar et al., 2005), reported controversial results in the same hSOD1G93A mice. While one study showed that activating autophagy reduced MN loss in hSOD1G93A mice (Fornai et al., 2008), two studies found that it caused an earlier onset of the disease and a reduced lifespan (Gill et al., 2009; Pizzasegola et al., 2009). Clinical trials by administrating therapeutic doses of lithium showed no effect in ALS patients (Chio et al., 2010).

These controversial findings raise a question of whether the observed AVs in fALS-linked spinal MNs reflect enhanced autophagy induction or impaired autophagic clearance. Addressing this question is critical for future therapeutic strategies for ALS clinical trials. Our study provides in vitro and in vivo evidence that progressive lysosomal deficits combined with impaired degradation of damaged mitochondria are the early pathological events in hSOD1G93A spinal MNs. The striking AV accumulation in ventral root axons suggests impaired retrograde transport of autophagosomes and impaired degradation of damaged mitochondria as early as at P40. Our findings provide a clue as why inducing autophagy alone, without compensatory rescue of LE transport and lysosomal deficits, failed to reduce mutant hSOD1 aggregates in the spinal MNs. Instead it augments MN degeneration and disease progression (Zhang et al., 2011), possibly due to enhanced autophagy stress and mitochondria pathology. Our recent study reveals that LE-loaded dynein-snapin complex drives the retrograde transport of axonal autophagosomes upon their fusion into amphisomes (Cheng et al., 2015). Efficient dynein-snapin coupling may help remove axonal autophagosomes engulfing aggregated proteins and dysfunctional organelles. Accumulation of vacuolated and dysfunctional mitochondria within distal axons early in the disease course can have catastrophic consequences by triggering axonal degeneration and denervation. This view is consistent with the notion that ALS is a dying-back type of neuropathy that initiates and progresses from distal to proximal portions of MNs (Gould et al., 2006). Such early autophagy stress and mitochondria pathology expedite progressive MN degeneration. Therefore, enhancing lysosome function, rather than autophagy induction, is an alternative therapeutic strategy for ALS-linked clinical trials.

Impaired Retrograde Transport Underlying Autophagy-Lysosomal Deficits

Intracellular transport is fundamental for maintaining neuronal homeostasis and survival. In axons, dynein is minus-end–directed motor that drives the retrograde transport of degradative organelles from axonal terminals to the soma where mature lysosomes are mainly localized and facilitate endolysosome membrane trafficking and lysosomal maturation (Ravikumar et al., 2005). Altered axonal transport was implicated in the ALS-associated pathogenesis (De Vos et al., 2007; Perlson et al., 2009; Williamson and Cleveland, 1999). In vivo analysis demonstrated axonal retrograde transport deficits in sciatic MNs but not in sciatic DRG sensory neurons of presymptomatic hSOD1G93A mice (Bilsland et al., 2010). These deficits become even worse at the symptomatic stage. Consistently, mutations in dynein motors or genes that regulate dyneinmediated retrograde transport cause fALS-like pathology and MN degeneration in mice and human patients (Dion et al., 2009; Hafezparast et al., 2003). Defects in retrograde transport retain late endocytic organelles and immature AVs engulfing damaged mitochondria and protein aggregates within axons rather than being delivered to the soma for degradation. This is confirmed by our TEM observations showing aberrant accumulation of autophagy-mitophagy intermediates in ventral root axons, and by our imunohistostaining showing clustered LC3-labeled AVs, some of which co-localized with mitochondria, within axons of the crossed hSOD1G93A/GFP-LC3 mice. Thus, our study provides clues that dynein-driven LE transport is essential for maturation and degradation of the autophagy-lysosome system in MNs.

Mutant hSOD1 Impairs Retrograde Transport by Interfering with Snapin-Dynein Complex

Our findings prompt us to address mechanistic questions as how mutant hSOD1 impairs LE transport and how snapin rescues this transport deficit. Mutant hSOD1 forms aggregates with the dynein complexes in the spinal MNs of asymptomatic hSOD1G93A mice and these aggregates interfere with axonal transport (Ligon et al., 2005; Sasaki et al., 2005). Three mutant forms of hSOD1 (G93A, G85R and A4V), but not WT hSOD1WT, interact with the dynein DIC (Zhang et al., 2007). These mutant hSOD1-DIC complexes were readily found in fALS-linked mice at the presymptomatic stages and increased with disease progression (Ström et al., 2008), suggesting that dynein is possible target of mutant hSOD1 toxicity. However, these studies raise a mechanistic question as to whether mutant hSOD1 aggregates interfere with the dynein-cargo attachment. It is particularly relevant because snapin acts as a dynein adaptor specific for LEs via binding DIC (Cai et al., 2010). We propose that hSOD1G93-DIC interaction interferes with snapin-DIC mediated recruitment of dynein motors to LEs, thus reducing their retrograde transport in hSOD1G93A MNs (Figure 5I). We found reduced association of dynein motor subunits including DIC and dynein heavy chain (DHC) with Rab7-labeled late endocytic organelles in P40 hSOD1G93A spinal cords compared to those from age-matched WT mice. Such reduced dynein tethering to LEs was not observed in age-matched hSOD1wt transgenic mice, suggesting a phenotype specifically associated with hSOD1G93A expression. Expressing snapin inhibits hSOD1G93A-DIC coupling, indicating competitive binding of snapin and hSOD1G93A with DIC. Thus, our study reveals a new mechanistic pathway through which mutant hSOD1 selectively impairs LE retrograde transport, which can be reversed by elevated snapin expression. We further show that introducing snapin transgene into cultured adult MNs and in vivo mouse model rescues autophagy-lysosome deficits, facilitates removal of damaged mitochondria, reduces MN death. Importantly, AAV9-snapin injection improves the motor coordination and prolongs the average lifespan of hSOD1G93A mice for 12 days in the current study. This is comparable to those studies by direct inhibiting cytochrome c induced MN apoptosis (Zhu et al., 2002) or by reducing the disease-modifier Epha4 signaling (Van Hoecke et al., 2012), both increase survival for about 11 days in the same mouse model. Therefore, enhancing dynein-mediated LE retrograde transport rescues autophagy-lysosome deficits caused by hSOD1G93A and ameliorates the disease phenotype in this disease mouse model.

Because snapin plays multivalent roles in intracellular trafficking, we cannot exclude the possibility that it also improves MN viability through other trafficking pathways, such as synaptic vesicle trafficking and synchronized fusion (Pan et al., 2009) and retrograde transport of signaling endosomes (Zhou et al., 2012). Interestingly, expressing the snapin-L99K mutant defective in DIC binding failed to rescue autophagy-lysosome deficits or reduce cell death in hSOD1G93A MNs, further supporting that snapin/dynein-mediated transport plays a major role in restoring autophagy-lysosomal function and delaying MN degeneration.

In summary, our study reveals that lysosome deficits and mitochondria pathology in early asymptomatic hSOD1G93A MNs are attributable to mutant hSOD1-induced impairment of endolysosomal trafficking. These early pathological changes impair the degradation of damaged mitochondria from distal axons of spinal MNs, thus causing them to be more vulnerable to dying-back degeneration. Elucidation of this early pathological mechanism is broadly relevant, because defective retrograde transport, lysosomal deficits, autophagy stress, and mitochondrial pathology are all associated with major neurodegenerative diseases including ALS, Huntington’s, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases (Nixon 2013). Therefore, enhancing clearance of damaged mitochondria and mutant protein aggregates by regulating endolysosomal trafficking may be a potential therapeutic strategy for ALS and perhaps other neurodegenerative diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Additional information can be found in Supplemental Information.

Mouse lines

B6.Cg-Tg (SOD1G93A) 1Gur/J mice expressing high copy number of the G93A mutant form of human SOD1 and B6SJL-Tg(SOD1)2Gur/J mice expressing wild-type human SOD1 were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory.

Adult MN Cultures

Mouse spinal cords were extruded from the decapitated neck and sectioned transversely at 500-µm intervals. After dissociation with 36 units/ml papain and 0.02% DNAse I for 30 min at 30°C, the tissue suspension was centrifuged and the pellet was triturated 3 times with glass pipettes. After cell debris and tissue pieces were filtered through a 70-µm cell strainer, MN suspension was enriched through OptiPrep gradient centrifugation and were re-suspended and plated on coverslips coated with 30 µg/ml poly-L-ornithine and 1 µg/ml laminin. MNs from paired WT and SOD1G93A littermates at early asymptomatic ages (P40 or P65) were plated on coverslips at the density of 1,000 cells per 12-mm coverslip.

Assays for Mature Cathepsins B and D

To label active cathepsin D in mature lysosomes, live adult MNs or DRG neurons were incubated with 1 µM Bodipy-FL-pepstatin A in culture medium for 1 hr at 37°C. An active form of cathepsin B was labeled by the cresyl violet fluorogenic substrate CV-(Arg-Arg)2 (Magic Red). Briefly, live neurons were incubated with staining solution (MR-RR2) at 1:1300 dilution for 15 min at 37°C, then washed 3 times by HA medium for imaging. Reduced staining of Bodipy FLpepstatin A or Magic Red in neurons reflects impaired lysosomal maturation.

Assay for Autophagic Maturation

Neurons were infected with Lenti-virus expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3. As soon as autophagy is induced, GFP, but not mRFP, undergoes rapid degradation in mature autolysosomes. Lysosomal defects result in both GFP and mRFP co-localized signals retained in immature autophagosomes. Co-localization between RFP-LC3 and GFP-LC3 signals was analyzed using ImageJ JACoP (NIH) with Mander's overlap coefficient. The signals were extracted from background by setting an appropriate threshold and by applying Gaussian blur to remove the background noise. Mander’s overlap coefficient was calculated as the percentage of pixel intensity of GFP merged with RFP relative to the total RFP intensity, with 1 being full co-localization and 0 indicating no co-localization.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Prism (Graphpad Software). Two groups were compared using F-test or Mann-Whitney (sample size n < 30) or Student’s t-test (sample size n ≥ 30). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Differences were considered significant with p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Lysosomal deficit is an early pathological event in fALS-like SOD1G93A mouse MNs

Reduced autophagy clearance contributes to mitochondrial pathology in fALS MNs

hSOD1G93A impairs retrograde transport by disturbing dynein-endosomes coupling

Enhancing endosome trafficking by snapin rescues autophagy-lysosomal deficits

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Sheng lab for technical assistance and discussion, S. Cheng and V. Crocker at the NINDS Electron Microscopy Facility for TEM analysis, D. Schoenberg for proof editing. The work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NINDS, NIH ZIA HS003029 and ZIA NS002946 (Z-H. Sheng).

Abbreviation

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- AV

autophagic vacuole

- fALS

familial ALS

- sALS

sporadic ALS

- DIV

days in vitro

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- LE

late endosome

- MLBs

multilamellar bodies

- MN

motor neuron

- P40

postnatal day 40

- SOD1

Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase 1

- Magic Red

the cresyl violet fluorogenic substrate CV-(Arg-Arg)2

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATMENT

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Animal care and use were carried out in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the NIH, NINDS/NIDCD Animal Care and Use Committee.

Author Contributions:

Y.X. conducted experiments and data analysis in brain/spinal sections and neuron cultures; B.Z. conducted experiments and data analysis in adult cultured motor neurons; M.-Y.L. performed immuno-isolation and biochemical analysis; S.W. performed EM imaging; K.D.F. designed and prepared AAV9-snapin vectors for viral injection; Z.-H.S. is the senior author who designed the project; Y.X. and Z.-H.S. wrote the manuscript

REFERENCES

- Beal MF. Mitochondria, free radicals, and neurodegeneration. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1996;6:661–666. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsland LG, Sahai E, Kelly G, Golding M, Greensmith L, Schiavo G. Deficits in axonal transport precede ALS symptoms in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:20523–20528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006869107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q, Lu L, Tian J-H, Zhu Y-B, Qiao H, Sheng Z-H. Snapin-regulated late endosomal transport is critical for efficient autophagy-lysosomal function in neurons. Neuron. 2010;68:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo K, Nassif M, Valenzuela V, Rojas F, Matus S, Mercado G, Court FA, van Zundert B, Hetz C. Trehalose delays the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by enhancing autophagy in motoneurons. Autophagy. 2013;9:1308–1320. doi: 10.4161/auto.25188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics--fusion, fission, movement, and mitophagy--in neurodegenerative diseases. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18:R169–R176. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X-T, Zhou B, Mei-Yao Lin M-Y, Qian Cai Q, Sheng Z-H. Axonal autophagosomes recruit dynein for retrograde transport through fusion with late endosomes. Journal of Cell Biology. 2015;209:377–386. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chio A, Borghero G, Calvo A, Capasso M, Caponnetto C, Corbo M, Giannini F, Logroscino G, Mandrioli J, Marcello N, et al. Lithium carbonate in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: lack of efficacy in a dose-finding trial. Neurology. 2010;75:619–625. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ed9e7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland DW, Rothstein JD. From Charcot to Lou Gehrig: deciphering selective motor neuron death in ALS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:806–819. doi: 10.1038/35097565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino M, Ferri A, Valle C, Carrì MT. Mitochondria and ALS: implications from novel genes and pathways. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;55:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos KJ, Chapman AL, Tennant ME, Manser C, Tudor EL, Lau K-F, Brownlees J, Ackerley S, Shaw PJ, McLoughlin DM, et al. Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosislinked SOD1 mutants perturb fast axonal transport to reduce axonal mitochondria content. Human Molecular Genetics. 2007;16:2720–2728. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion PA, Daoud H, Rouleau GA. Genetics of motor neuron disorders: new insights into pathogenic mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:769–782. doi: 10.1038/nrg2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornai F, Longone P, Cafaro L, Kastsiuchenka O, Ferrucci M, Manca ML, Lazzeri G, Spalloni A, Bellio N, Lenzi P, et al. Lithium delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:2052–2057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708022105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust KD, Wang X, McGovern VL, Braun L, Bevan AK, Haidet AM, Le TT, Morales PR, Rich MM, Burghes AHM. Rescue of the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in a mouse model by early postnatal delivery of SMN. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:271–274. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Gal J, Ström A-L, Kilty R, Zhang F, Zhu H. p62 accumulates and enhances aggregate formation in model systems of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:11068–11077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill A, Kidd J, Vieira F, Thompson K, Perrin S. No benefit from chronic lithium dosing in a sibling-matched, gender balanced, investigator-blinded trial using a standard mouse model of familial ALS. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng HX. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafezparast M, Klocke R, Ruhrberg C, Marquardt A, Ahmad-Annuar A, Bowen S, Lalli G, Witherden AS, Hummerich H, Nicholson S, et al. Mutations in dynein link motor neuron degeneration to defects in retrograde transport. Science. 2003;300:808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.1083129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri M, Millane G, Guimond MP, Guay G, Dennis JW, Nabi IR. Biogenesis of multilamellar bodies via autophagy. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11:255–268. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris H, Rubinsztein DC. Control of autophagy as a therapy for neurodegenerative disease. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2012;8:108–117. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilieva H, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Non-cell autonomous toxicity in neurodegenerative disorders: ALS and beyond. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2009;187:761–772. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J-S, Tian J-H, Pan P-Y, Zald P, Li C, Deng C, Sheng Z-H. Docking of axonal mitochondria by syntaphilin controls their mobility and affects short-term facilitation. Cell. 2008;132:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselyov K, Jennigs JJ, Rbaibi Y, Chu CT. Autophagy, mitochondria and cell death in lysosomal storage diseases. Autophagy. 2007;3:259–262. doi: 10.4161/auto.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts D, Storkebaum E, Morimoto M, Del-Favero J, Desmet F, Marklund SL, Wyns S, Thijs V, Andersson J, van Marion I, et al. VEGF is a modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice and humans and protects motoneurons against ischemic death. Nat Genet. 2003;34:383–394. doi: 10.1038/ng1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Sato Y, Nixon RA. Lysosomal Proteolysis Inhibition Selectively Disrupts Axonal Transport of Degradative Organelles and Causes an Alzheimer's-Like Axonal Dystrophy. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:7817–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6412-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhang X, Le W. Altered macroautophagy in the spinal cord of SOD1 mutant mice. Autophagy. 2008;4:290–293. doi: 10.4161/auto.5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon LA, LaMonte BH, Wallace KE, Weber N, Kalb RG, Holzbaur ELF. Mutant superoxide dismutase disrupts cytoplasmic dynein in motor neurons. Neuroreport. 2005;16:533–536. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200504250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maday S, Wallace KE, Holzbaur ELF. Autophagosomes initiate distally and mature during transport toward the cell soma in primary neurons. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2012;196:407–417. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magrané J, Manfredi G. Mitochondrial function, morphology, and axonal transport in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2009;11:1615–1626. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinkovic P, Reuter MS, Brill MS, Godinho L, Kerschensteiner M, Misgeld T. Axonal transport deficits and degeneration can evolve independently in mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:4296–4301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200658109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2004;15:1101–1111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto N, Nagai M, Ohta Y, Miyazaki K, Kurata T, Morimoto M, Murakami T, Takehisa Y, Ikeda Y, Kamiya T, et al. Increased autophagy in transgenic mice with a G93A mutant SOD1 gene. Brain Research. 2007;1167:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mórotz GM, De Vos KJ, Vagnoni A, Ackerley S, Shaw CE, Miller CCJ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated mutant VAPBP56S perturbs calcium homeostasis to disrupt axonal transport of mitochondria. Human Molecular Genetics. 2012;21:1979–1988. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA. The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nature Publishing Group. 2013;19:983–997. doi: 10.1038/nm.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osellame LD, Duchen MR. Quality control gone wrong: mitochondria, lysosomal storage disorders and neurodegeneration. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;171:1958–1972. doi: 10.1111/bph.12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan P-Y, Tian J-H, Sheng Z-H. Snapin facilitates the synchronization of synaptic vesicle fusion. Neuron. 2009;61:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlson E, Jeong GB, Ross JL, Dixit R, Wallace KE, Kalb RG, Holzbaur ELF. A Switch in Retrograde Signaling from Survival to Stress in Rapid-Onset Neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:9903–9917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0813-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzasegola C, Caron I, Daleno C, Ronchi A, Minoia C, Carrì MT, Bendotti C. Treatment with lithium carbonate does not improve disease progression in two different strains of SOD1 mutant mice. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10:221–228. doi: 10.1080/17482960902803440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Acevedo-Arozena A, Imarisio S, Berger Z, Vacher C, O’Kane CJ, Brown SDM, Rubinsztein DC. Dynein mutations impair autophagic clearance of aggregate-prone proteins. Nat Genet. 2005;37:771–776. doi: 10.1038/ng1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, Donaldson D, Goto J, O'Regan JP, Deng HX. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Floto RA, Berger Z, Imarisio S, Cordenier A, Pasco M, Cook LJ, Rubinsztein DC. Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2005;170:1101–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Warita H, Murakami T, Shibata N, Komori T, Abe K, Kobayashi M, Iwata M. Ultrastructural study of aggregates in the spinal cord of transgenic mice with a G93A mutant SOD1 gene. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0939-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C, Fraldi A, Jahreiss L, Spampanato C, Venturi C, Medina D, de Pablo R, Tacchetti C, Rubinsztein DC, Ballabio A. A block of autophagy in lysosomal storage disorders. Human Molecular Genetics. 2007;17:119–129. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan X, Chiang P-M, Price DL, Wong PC. Altered distributions of Gemini of coiled bodies and mitochondria in motor neurons of TDP-43 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 2010;107:16325–16330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003459107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng Z-H, Cai Q. Mitochondrial transport in neurons: impact on synaptic homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:77–93. doi: 10.1038/nrn3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ström A-L, Shi P, Zhang F, Gal J, Kilty R, Hayward LJ, Zhu H. Interaction of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-related mutant copper-zinc superoxide dismutase with the dynein-dynactin complex contributes to inclusion formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:22795–22805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800276200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoecke A, Schoonaert L, Lemmens R, Timmers M, Staats KA, Laird AS, Peeters E, Philips T, Goris A, Dubois BENED, et al. EPHA4 is a disease modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in animal models and in humans. Nat Med. 2012;18:1418–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson TL, Cleveland DW. Slowing of axonal transport is a very early event in the toxicity of ALS-linked SOD1 mutants to motor neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:50–56. doi: 10.1038/4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Strom AL, Fukada K, Lee S, Hayward LJ, Zhu H. Interaction between Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)-linked SOD1 Mutants and the Dynein Complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:16691–16699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li L, Chen S, Yang D, Wang Y, Zhang X, Wang Z, Le W. Rapamycin treatment augments motor neuron degeneration in SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Autophagy. 2011;7:412–425. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.4.14541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Cai Q, Xie Y, Sheng Z-H. Snapin recruits dynein to BDNF-TrkB signaling endosomes for retrograde axonal transport and is essential for dendrite growth of cortical neurons. CellReports. 2012;2:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Stavrovskaya IG, Drozda M, Kim BYS, Ona V, Li M, Sarang S, Liu AS, Hartley DM, Wu DC, et al. Minocycline inhibits cytochrome c release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature. 2002;417:74–78. doi: 10.1038/417074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YB, Sheng ZH. Increased Axonal Mitochondrial Mobility Does Not Slow Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)-like Disease in Mutant SOD1 Mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:23432–23440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.