Abstract

Venous leg ulcers are the most frequent form of wounds seen in patients. This article presents an overview on some practical aspects concerning diagnosis, differential diagnosis and treatment. Duplex ultrasound investigations are essential to ascertain the diagnosis of the underlying venous pathology and to treat venous refluxes. Differential diagnosis includes mainly other vascular lesions (arterial, microcirculatory causes), hematologic and metabolic diseases, trauma, infection, malignancies. Patients with superficial venous incompetence may benefit from endovenous or surgical reflux abolition diagnosed by Duplex ultrasound. The most important basic component of the management is compression therapy, for which we prefer materials with low elasticity applied with high initial pressure (short-stretch bandages and Velcro-strap devices). Local treatment should be simple, absorbing and not sticky dressings keeping adequate moisture balance after debridement of necrotic tissue and biofilms are preferred. After the ulcer is healed compression therapy should be continued in order to prevent recurrence.

Keywords: Venous ulcer, Venous insufficiency, Compression therapy, Wound care

How Do Venous Ulcers Develop?

Wounds are generally considered of traumatic origin, whereas ulcers are generally considered of internal etiology/pathology, leading to preexisting tissue damage before the skin breaks down. With other words, we would define a wound as a defect in the normal skin while an ulcer is a defect in previously damaged skin. Such a definition would explain the necessity to concentrate in ulcer patients first on the treatment of the underlying causes for the preexisting tissue changes. This manuscript will focus on the most frequent cause of leg ulcers related to venous disease. This would include varicose veins, venous insufficiency including venous insufficiency induced lymphedema, and the postthrombotic syndrome. Leg edema is a common manifestation of these disorders and is often accompanied by morbid obesity. The presence of a large abdominal pannus can increase intraabdominal and distal venous pressure to contribute to leg edema by slowing venous return.

Although the arteries deliver blood to the leg and the veins return the blood to the heart, the only place where exchange of nutrients and waste products occur is in the capillaries that are situated in between the arterial and venous systems. A venous ulcer is the end result of tissue ischemia as a result of damage and eventual destruction of the capillaries that deliver oxygen and nutrients to the skin and subcutaneous tissues. They receive products of metabolism from the tissues, although most waste products and water are resorbed by the lymphatics. The sequence of events that lead to this capillary damage starts when edema begins to collect in the legs.1

Venous edema is caused either by valvular incompetence, by venous obstruction or both.

The normal flow of venous blood back to the heart in the upright position requires contraction of the calf muscles. The deep veins are located beneath the fascia in the muscular compartments of the calf. In the upright position blood has to overcome gravity to be transported from the foot up to the heart. In the upright position venous return is accomplished by a very complex cooperation of several pumping mechanisms, starting form the foot pump upwards, among which the muscular contractions of the calf muscles during walking (“calf muscle pump”) is the most effective part.2 When the muscles relax, the column of blood is prevented from falling all the way down the leg toward the foot due to a series of valves that close. This process works well as long as the valves are competent. In this case, the pressure in the veins of the distal lower extremity, which correspond to the weight of the blood column between the measuring point and the right heart, will drop from 80–90 mm Hg at foot level in the standing position to 20–30 mm Hg during walking.2 Unfortunately if valve leakage occurs the blood column builds in volume and causes the veins to dilate (venous reflux). This venous reflux may involve superficial, deep veins or both systems. Several duplex studies have shown that in patients of venous leg ulcers 80% present with superficial reflux, half of them in combination with deep venous reflux.3

During walking the blood column in the incompetent veins will oscillate up and down and the peripheral venous pressure will not fall as in normals. This situation is called ambulatory venous hypertension, which is transmitted into the capillaries and which is the key in explaining the formation of edema and of skin changes. Eventually the increased venous pressure begins to dilate the veins that connect to the superficial leg compartment that is outside of the muscle layers. It is very difficult for blood in the superficial leg compartment to return to the heart since there are no muscles to move the blood toward the heart. The net result is an increase in venous blood volume in the leg. The veins are very distensible but there is a limit. When they expand beyond a certain size the endothelium begins to crack. This over-distention and increased venous pressure occurs in the capillary bed as well with very serious consequences. Stasis in the capillaries along with endothelial cracks results in activation of white cells to seal the endothelial cracks. Eventually obliteration of the capillaries occurs resulting in failure to provide nourishment to the tissues and remove waste products.1

Increased fluid filtration leads to an increase of the lymphatic drainage. When this increased lymph drainage overcomes the capacity of the lymphatics lymphedema will develop. Lymphatics are always involved in any kind of chronic edema and of leg ulcers and frequently clinical signs of lymphedema develop as a consequence of venous disease.4

This lymphatic involvement has considerable consequences concerning the local immune response.

Chronic venous insufficiency is a term encompassing the clinical signs of chronic edema, skin changes on the lower leg and ulceration.

This may also occur when the venous pressure in the leg veins is increased due to obesity. As the abdominal girth increases the intraabdominal venous pressure increases and reduces venous blood flow from the legs.5 This is reflected in increased leg blood volume, valvular incompetence and reflux of blood flow between leg muscular contractions. The net result is the same as when primary venous valve incompetence occurs as described above. As the persons weight increases the venous pressure and leg swelling continue to worsen.

Congestive heart failure with increased right heart pressures due to decreased cardiac output can produce significant leg swelling and be associated with many of these venous stasis changes.

In about 50% of the cases of CVI leg swelling, skin changes and leg ulceration are due to the postthrombotic syndrome (PTS). This results from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the legs most often in the proximal venous segments and is much less commonly seen in those after isolated calf DVT. If a person suffers a recurrent thrombosis the incidence of this syndrome increases six fold.6–8 A PTS, most frequently characterized by swelling, rarely by ulceration, occurs 30–50% of the time following an episode of DVT and may not appear for 2–10 years after the initial thrombotic event. We know that the use of appropriate compression stockings of at least 20–30 mm Hg and preferably 30 40 mm Hg pressure decreases the incidence of the postthrombotic syndrome by 50% during the first 2 years after the thrombosis.9

How Do We Diagnose Venous Ulcers?

A venous ulcer may result from fragile skin that is very susceptible to trauma. Often considerable leakage of fluid through the ulcerated area will occur leading to irritation and maceration of the surrounding skin. If this condition is untreated mummification of the skin and subcutaneous tissues can also occur with resulting darkening and hardening of the skin along with the development of dermatitis. The venous ulcer may exhibit pigmentation and hemosiderosis of the surrounding tissues. Fibrosis and sclerosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissues result in “lipodermatosclerosis” (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Bilateral lipodermatosclerosis, often a precursor of ulceration.

The typical location is in the so called “gaiter” area around the medial malleolus. A venous ulcer may also occur adjacent to the lateral malleolus especially in cases where there is reflux in the small saphenous vein. Posttraumatic ulcers are frequently localized over the shin. Stasis ulcers can also occur in other distal parts of the leg. Venous ulcers respond very quickly to appropriate compression therapy often healing in a matter of weeks. The arterial pulses in the extremity are typically normal unless arterial insufficiency is also present. A careful differential diagnosis is required to exclude other causes of skin ulceration. Failure of the ulcer to respond to compression therapy should create suspicion that another cause may be responsible such as a basal or squamous cell lesion or pyoderma gangrenosum. Arteriolar necrosis above the outer malleolus in hypertensive patients has been described as Martorell's ulcer and is often confused with pyoderma and calciphylaxis.10

Arterial ulcers, skin cancers, pyoderma gangrenosum, and other inflammatory ulcers may be confused with venous ulcers particularly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. Especially when ulcers do not improve with adequate therapy, non-venous etiology and referral to a specialist needs to be considered.

Improper ulcer moisture or infection can also be responsible for slow healing lesions.11

The laboratory diagnosis should consist of a carefully done venous duplex ultrasound examination to identify venous reflux and/or obstruction suggestive of a previous thrombosis and to exclude the presence of acute DVT. Reflux examination should be done in the standing position assessing all of the major venous segments for reflux. This is done by intermittent squeezing of the leg under ultrasound visualization to assess and quantify degrees of reflux in the superficial and deep venous system.

A careful Duplex investigation does not have just diagnostic importance but has also considerable therapeutic implications:

Although appropriate compression therapy is the mainstay of treatment for venous ulcers and the resulting edema, an important aspect of the care of these patients is to correct any significant superficial and perforator reflux with venous ablation or sclerotherapy. If superficial and deep venous reflux is present, correcting the superficial reflux will improve the overall healing rate of these ulcers as well as decrease the incidence of recurrence.12,13

Initial Assessment

The management of patients with venous ulcers begins with an evaluation of the arterial circulation to the leg. Examination starts with palpating pulses, checking for secondary signs of decreased perfusion such as color, temperature, presence or absence of hair on the toes, and capillary refill. The exam can be repeated with time to evaluate the efficacy of therapy. Auscultation with a hand-held Doppler is mandatory when pulses are not palpable, e.g. due to edema, and should include measuring the ankle pressure and calculating the ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI). Normally the leg pressures should be at least 80% of those in the arm and when the ABPI is <0.5 (= critical ischemia) applying sustained compression to the extremity is contraindicated. In these cases further studies should be done to evaluate the circulation and the feasibility for revascularization.14

Evaluation of sensory function should also be done including checking vibratory sense. Testing vibratory sense with a tuning fork provides a quick measure of nerve damage in the extremity.

Another important aspect is to assess the ulcer for infection and the presence of biofilm and necrotic tissue. Debridement and selection of culture or biopsy driven systemic antibiotics when indicated should be employed. Most venous stasis ulcers are not clinically infected and routine use of systemic antibiotics is not advised. Similarly topical antibiotics are not necessary and may result in the appearance of strange fungal and other ulcer organisms that complicate treatment.

How Do We Treat Venous Leg Ulcers?

Local Dressings

The treatment of these ulcers begins with appropriate local ulcer care. Debridement of devitalized tissue including biofilm, elimination of serious infection, and proper moisture balance are key elements.11

One of the most controversial aspects is the selection of topical ulcer dressings. The key factor is controlling ulcer drainage and using products that can wick away the drainage to prevent maceration of the ulcer. Many practitioners are very fond of the use of specialized and expensive dressings including silver containing products. There is very little evidence in randomized trials for most of these products.15 We prefer to use simple, inexpensive, absorbing and non-adherent products in these ulcers. A very important factor in ulcer healing is proper moisture balance in the ulcer. Excessive ulcer moisture or dryness impedes healing.11 The practice of keeping ulcers open to the air that in the past was thought to promote healing actually slows down this process.

Compression Therapy

The single most important aspect in the healing of venous ulcers is appropriate compression therapy.14,16 Bandages may be classified as long stretch (elastic), or short stretch (inelastic). Elastic bandages are applied with sufficient tension to make sure they do not fall down when the patient walks. Blood and fluid that leaks out of the deep muscular compartment causes the bandage to expand because of its elastic properties. This provides little or no control of edema. As the edema increases the elastic bandage expands (“gives way”) to accommodate the swelling. The bandage becomes tighter and tighter until the bandage can no longer expand. Discomfort and pain under the bandage increases until the patient can no longer tolerate the compression. A rubber band effect occurs and if the compression bandage is not removed skin breakdown can occur. A surgical stocking used in patients with edema often can cause these skin lesions when used in patients with edema. The use of elastic compression to treat venous stasis ulcers often results in “stalled” or very slow healing and in many cases the ulcers will worsen using this form of compression. The basic principle of increasing flow out of the leg to reduce venous stasis and improve arterial inflow is poorly accomplished by elastic modalities.

Short stretch products include cotton bandages (e.g. Comprilan®, Rosidal®), zinc paste bandages, Velcro strap devices (e.g. CircAid®, Farrow wraps®), and multilayer wraps (e.g. Profore®, Coban 2®). These products need to be applied with initially high pressure. There is an immediate pressure drop due to decrease in the size of the leg due to instant edema reduction resulting in a low resting pressure after short time. This allows short stretch products to be worn day and night with excellent patient comfort. Ideally good compression should always be combined with walking exercises.14 This process reduces edema, decreasing the pressure at the venous end of the capillary facilitating flow and hence removal of waste products from the tissues. This decrease of ambulatory venous hypertension allows increased arterial perfusion to the capillaries delivering nutrients and oxygen to the tissues. As this process continues healing of the ulcer is facilitated.

The most frequent cause for poor ulcer healing is the lack of a proper compression technique by the bandagers. This applies also to “experienced staff” which was obviously never trained in applying adequate bandages. Most bandages are “under dosed.”17

Using inelastic material the initial sub-bandage pressure on the lower leg in patients with intact arterial inflow should be 40–60 mm Hg or higher.

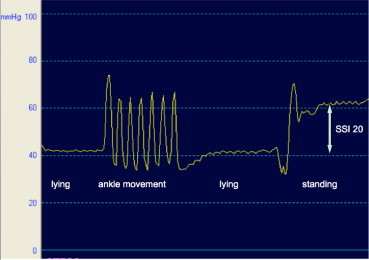

There are several devices that can be used to measure pressure changes under bandages or stockings including a Picopress® (Microlab, Padova, Italy) (that consists of a flat air filled pressure probe placed under the garment or bandage.18 The probe is filled with a small amount of air connected to a transducer that measures pressure. This enables the pressure characteristics of different bandages and stockings to be measured. Using this device we can measure the “dose” of compression devices that allows more precise evaluation between compression modalities in clinical trials. These measurements also facilitate selection of the optimal product for the care of an individual patient and are very helpful for training purposes how to apply a proper bandage. The pressure under a garment at rest is known as the resting pressure and the working pressure refers to the pressure when walking. The difference between standing and resting is referred to as the static stiffness index (SSI). For example if the resting pressure is 40 and the standing pressure is 50 the SSI is 10. Elastic products have a SSI of <10 while the short stretch product could have much a higher SSI approaching 50 or more in certain cases19 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Measurement of pressure under an inelastic bandage 12 cm above the inner ankle. Resting pressure is 40 mm Hg. During 7 dorsiflexions there are high pressure fluctuations corresponding to a massaging effect of the inelastic material. By standing up the pressure rises to 60 mm Hg, the SSI (standing minus lying pressure) is 20.

Compression Therapy in Accompanying Arterial Disease

Several studies and meta-analyses have shown that specially designed intermittent pneumatic pressure pumps (IPC) can be very useful to treat arterial and mixed arterial-venous ulcers.20,21 The beneficial effects of IPC is mainly explained by a release of vasoactive mediators from the endothelial cells in the venules due to an intermittent increase of the shear stress in the blood capillaries by the massaging effect of the pump.22

Inelastic bandages in combination with walking also exert a comparable massaging effect on the leg (see Fig. 2) which may explain the fact that many times stasis ulcers can be healed in the presence of arterial insufficiency particularly in the non-diabetic using short-stretch compression.21 In any case with mixed arterial and venous insufficiency it is critical to use a compression system where the resting pressure is less than the leg arterial pressure.14 Knowing the pressure characteristics of the bandage is critical in selecting the optimal product. The tendency to apply Stockinet type compression, elastic bandages, or low-pressure elastic hose (surgical stockings) to those with arterial insufficiency has major disadvantages. As the elastic product expands to accommodate increasing edema, a “rubber band” like effect is produced that can lead to further skin damage and ischemic changes in the extremity. A much safer approach is to use several short-stretch bandages on the extremity with reduced pressure. When properly applied this results in an initial 20–40 mm Hg resting pressure and a SSI of >10. Such bandages have been termed “modified compression.”14 In patients with arterial occlusive disease and an ABI > 0.6, it could be shown that modified compression consisting in inelastic bandages applied with a pressure up to 40 mm Hg are able to increase arterial flow and venous pumping function.23 There is a definite learning curve for proper application of these products but they are very effective in reducing edema and their low resting pressure provides patient comfort.

Basic therapy of mixed, arterial-venous ulcers still consist in modified compression and walking exercises.24 Abolishment of venous reflux may also be beneficial in such patients.25

Compression Products

In patients with adequate circulation a wide variety of products may be used. A four-layer bandage system is quite popular and although these layers are mostly elastic, the friction between the layers increases the SSI. They are much less technically demanding to apply. Another popular and effective method is the use of paste bandages (Unna's boot) which are “zero-stretch” products that when properly applied can yield very high SSI values. They can be used as the primary dressing in cases where diffuse eczema is present and in conjunction with short stretch bandages (Fig. 3). As the edema resolves the extremity decreases in size and the bandages become loose requiring reapplication after several days.

Figure 3.

Typical venous ulcer, healed after 11 weeks of compression therapy using high pressure Unna boot bandages.

Recently a Velcro compression system has become available that can be tailored to the individual patient in the ulcer clinic and used as an alternative to compression bandages. This system involves a large Velcro wrap that is trimmed according to the calf and ankle measurements and employs a unique measuring system that is easy to use and provides predictable pressures on the leg due to an additional pressure monitoring card. These devices are short-stretch products that have a low resting pressure and high working pressure with an average SSI of >20 in the typical patient. The advantages include self-management, enabling the patient to change the dressings frequently and maintain a consistent pressure profile with a compression system that does not require special skills to apply. Velcro band devices are used in selected patients without heavily draining ulcers. They can also be introduced after initial therapy with the standard 4 layer bandages or short-stretch bandages.

When the Ulcer is Healed

A major problem once healing of the leg ulcer has occurred is to prevent recurrence. This is often difficult since it requires the patient to wear some form of compression on a long-term basis. It has been traditional to prescribe compression stockings for these patients but many pitfalls may occur. A sizeable percentage of patients with venous stasis ulcers have a level of edema that is difficult to control with 30–40 mm Hg stockings. These stockings become tighter on the leg since an elastic product expands to accommodate the increased edema. The SSI of these products is close to zero. Eventually the material is stretched to the maximum and the stocking acts like a tourniquet on the leg. This can result in further skin damage including ulcers. Donning and doffing becomes more difficult and with time the patient stops wearing the stockings altogether. Another major compliance problem occurs in patients with arthritis, decreased arm or hand strength, limited flexibility, age, surgery, and joint problems to mention a few. These individuals find donning and doffing stockings a difficult or impossible task. Aids for application and stocking removal are often awkward and the techniques required hard to master. Also for these patients Velcro-band devices are frequently a better alternative.

A major obstacle to long-term edema control is the obese patient. Many individuals have a large abdominal girth that increase venous pressure in the abdominal, pelvic, and leg veins producing edema and venous stasis. In some individuals this progresses to venous insufficiency-induced lymphedema. This degree of edema is virtually impossible to control in most patients using even high-pressure support stockings (Fig. 2). These patients often are unable to bend at the waist and are unable to apply or remove stockings. Frequently these patients are seen in the ulcer clinic with recurrent ulceration and confessing that they have not been wearing their hose. Many of us caring for these individuals feel they should never have been prescribed stockings in the first place. Fortunately Velcro compression devices represent a very effective compression solution for these individuals. These devices have a well-tolerated resting pressure and a high working pressure with an average SSI of more than 20. They are easy to apply and remove and can be adjusted by the patient. The devices can be tightened as the edema decreases, or loosened with patient discomfort occurs. Products from five companies are available and come in a variety of configurations for the calf, and foot. The disadvantage is that these products are expensive, require special fitters, and are cosmetically unappealing in some cases. Nevertheless they enable those to control edema long term where stockings are not appropriate or cannot be used. Finally these devices are ideal for those seniors who cannot manage stockings.

A number of pneumatic compression devices have appeared which can also be used in those with extreme edema or recurrent ulceration where other measures have failed, in addition to conventional compression devices. Using these devices on a part term basis during the day can be very helpful (adequate compliance provided), especially in patients who cannot walk or who are immobile.21,26 Very recently a new pump has become available that is an inflatable stocking providing 30–40 mm Hg calf and foot pressure27: The device consists of a sleeve applied to the leg and then an attached miniature pump inflates the sleeve to the appropriate pressure. The pressure is readjusted by the device every 30 min. The device also converts to a pneumatic compression device when plugged in. In many cases these pumps are expensive but under certain circumstances are covered by insurance.

Conclusions

Venous ulcers represent a common and often poorly treated problem. It is important to perform a proper differential diagnosis to exclude other important conditions particularly arterial insufficiency. A clear understanding of the pathophysiology of venous-related lesions is also mandatory. Specific knowledge regarding local ulcer care including minimizing infection and proper moisture balance in the ulcer bed is essential to achieve proper healing. One of the most important yet poorly understood aspects of the care of venous ulcers is compression therapy. One must be familiar with the concepts of short and long stretch compression and how to utilize the various products depending upon the individual patient's needs. Preventing recidivism through the use of compression products appropriate to the specific patient is essential.

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Bergan J.J., Schmid-Schönbein G.W., Coleridge-Smith P.D. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(5):488–498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner A.M.N., Fox R.H. John Libbey; London, Paris: 1989. The Return of Blood to the Heart. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perrin M. Rationale for surgery in the treatment of venous ulcers of the leg. Phlebolymphology. 2004;45:267–284. http://www.phlebolymphology.org/wp-content/pdf/Phlebolymphology45.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raju S., Furrh JBt, Neglen P. Diagnosis and treatment of venous lymphedema. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugerman H.J., Sugerman E.L., Wolfe L., Kellum J.M., Schweitzer M.A., DeMaria E.J. Risks and benefits of gastric bypass in morbidly obese patients with severe venous stasis disease. Ann Surg. 2001;234:41–46. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200107000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puggioni A., Kalra M., Gloviczki P. Practical aspects of the postthrombotic syndrome. Dis Mon. 2005;51:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn S.R. The post-thrombotic syndrome: the forgotten morbidity of deep venous thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-5574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heit J.A. Venous stasis syndrome: the long-term burden of deep vein thrombosis. Hosp Med. 2003;64:593–598. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2003.64.10.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen J.M., Akl E.A., Kahn S.R. Pharmacologic and compression therapies for postthrombotic syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(2):308–320. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hafner J., Nobbe S., Partsch H. Martorell hypertensive ischemic leg ulcer. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:961–968. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zulkowski K. Diagnosing and treating moisture-associated skin damage. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25:231–236. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000414707.33267.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas C.A., Holdstock J.M., Harrison C.C., Price B.A., Whiteley M.S. Healing rates following venous surgery for chronic venous leg ulcers in an independent specialist vein unit. Phlebology. 2013;28:132–139. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2012.011097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulkarni S.R., Slim F.J., Emerson L.G. Effect of foam sclerotherapy on healing and long-term recurrence in chronic venous leg ulcers. Phlebology. 2013;28:140–146. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2011.011118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Union of Ulcer Healing Societies (WUWHS) MEP Ltd; London: 2008. Principles of Best Practice: Compression in Venous Leg ulcers. A Consensus Document. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palfreyman S.J., Nelson E.A., Lochiel R., Michaels J.A. Dressings for healing venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jul 19;(3):CD001103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001103.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Meara S., Cullum N., Nelson E.A., Dumville J.C. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11:CD000265. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000265.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller A., Müller M.L., Calow T., Kern I.K., Schumann H. Bandage pressure measurement and training: simple interventions to improve efficacy in compression bandaging. Int Wound J. 2009 Oct;6(5):324–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2009.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partsch H. Innovations in venous ulcer management. Wounds Int. 2010;1(3) http://www.woundsinternational.com/practice-development/innovations-in-venous-leg-ulcer-management Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosti G., Mattaliano V., Partsch H. Inelastic compression increases venous ejection fraction more than elastic bandages in patients with superficial venous reflux. Phlebology. 2008;23:287–294. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2008.008009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalodiki E., Giannoukas A.D. Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) in the treatment of peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) – a useful tool or just another device? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007 Mar;33(3):309–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comerota A.J. Intermittent pneumatic compression: physiologic and clinical basis to improve management of venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2011 Apr;53(4):1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen A.H., Frangos S.G., Kilaru S., Sumpio B.E. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices – physiological mechanisms of action. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001 May;21(5):383–392. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosti G., Iabichella M.L., Partsch H. Compression therapy in mixed ulcers increases venous output and arterial perfusion. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marston W.A., Davies S.W., Armstrong B. Natural history of limbs with arterial insufficiency and chronic ulceration treated without revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2006 Jul;44(1):108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obermayer A., Göstl K., Partsch H., Benesch T. Venous reflux surgery promotes venous leg ulcer healing despite reduced ankle brachial pressure index. Int Angiol. 2008 Jun;27(3):239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partsch H. Intermittent pneumatic compression in immobile patients. Int Wound J. 2008 Jun;5(3):389–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2008.00477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanscheidt W., Ukat A., Partsch H. Dose-response of compression therapy for chronic venous edema – higher pressures are associated with greater volume reduction: two randomized clinical studies. J Vasc Surg. 2009 Feb;49(2):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]