Abstract

Pontibacter roseus is a member of genus Pontibacter family Cytophagaceae, class Cytophagia. While the type species of the genus Pontibacter actiniarum was isolated in 2005 from a marine environment, subsequent species of the same genus have been found in different types of habitats ranging from seawater, sediment, desert soil, rhizosphere, contaminated sites, solar saltern and muddy water. Here we describe the features of Pontibacter roseus strain SRC-1T along with its complete genome sequence and annotation from a culture of DSM 17521T. The 4,581,480 bp long draft genome consists of 12 scaffolds with 4,003 protein-coding and 50 RNA genes and is a part of Genomic Encyclopedia of Type Strains: KMG-I project.

Keywords: Aerobic, Gram-negative, Non-motile, Obligate aerobe, Halotolerant, Menaquinone, GEBA, KMG-I

Introduction

The genus Pontibacter was first reported by Nedashkovskaya et al. [1] where they identified and described a menaquinone producing strain isolated from sea anemones. Several new species of the same genus have been reported in the literature since then. In addition to Pontibacter roseus, there are eighteen species with validly published names belonging to Pontibacter genus as of writing this manuscript. Members of genus Pontibacter including P. roseus, is of interest for genomic research due to their ability to synthesize and use menaquinone-7 (MK-7) as the primary respiratory quinone as well as to facilitate functional genomics studies within the group. Strain SRC-1T (= DSM 17521 = CCTCC AB 207222 = CIP 109903 = MTCC 7260) is the type strain of Pontibacter roseus, which was isolated from muddy water from an occasional drainage system of a residential area in Chandigarh, India [2]. P. roseus SRC-1T was initially reported to be Effluviibacter roseus SRC-1T primarily due to its non-motile nature and fatty acid composition [2]. However, subsequent analysis of its fatty acid profile was shown to be more ‘Pontibacter-like’ and gliding motility was observed to be variable in other Pontibacter species [3]. Further, its DNA G + C content, which was originally reported as 59 mol% [2], was also emended to be 52.0–52.3 mol% [3], a value more representative of members of the genus Pontibacter. As such, it was reclassified as Pontibacter roseus SRC-1T [3]. Here we present a summary classification and features for Pontibacter roseus SRC-1T, along with the genome sequence and annotation of DSM 17521T.

Organism information

Classification and features

P. roseus SRC-1T cells are non-motile, stain Gram-negative, do not form spores and are rod-shaped approximately 1.0–3.0 μm in length and 0.3–0.5 μm in width [2]. It is an obligate aerobe which can grow at a wide temperature range of 4–37°C with the optimum being 30°C (Table 1 and [2]). P. roseus SRC-1T is a halotolerant microbe, can tolerate up to 8% NaCl and can utilize a wide range of sugars such as D-fructose, D-galactose, D-glucose, lactose, raffinose and sucrose as the sole source of carbon (Table 1 and [2]).

Table 1.

Classification and general features of Pontibacter roseus SRC-1T according to the MIGS recommendations [4], published by the Genomic Standards Consortium [5]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Bacteria | TAS [6] | ||

| Phylum Bacteroidetes | TAS [7,8] | ||

| Class Cytophagia | TAS [8,9] | ||

| Current classification | Order Cytophagales | TAS [10,11] | |

| Family Cytophagaceae | TAS [10,12] | ||

| Genus Pontibacter | TAS [2,3,10] | ||

| Species Pontibacter roseus | TAS [2,3,10] | ||

| Strain | SRC-1T | TAS [2,3,10] | |

| Gram stain | Gram-negative | TAS [2] | |

| Cell shape | Irregular rods | TAS [2] | |

| Motility | Non-motile | TAS [2] | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | TAS [2] | |

| Temperature range | 4–37°C | TAS [2] | |

| Optimum temperature | 30°C | TAS [2] | |

| Salinity | Halotolerant | TAS [2] | |

| Relationship to oxygen | Obligate aerobe | TAS [2] | |

| Carbon source | Sugars (Glucose, Galactose etc.) | TAS [2] | |

| TAS [2] | |||

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Wastewater, aquatic | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-6.2 | pH | pH 6.0–10.0 | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Known pathogenicity | Not reported | |

| Biosafety level | 1 | NAS | |

| MIGS-23 | Isolation | Muddy water | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Chandigarh, India | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-5 | Time of sample collection | Before 2006 | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 30.733 | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 76.779 | TAS [2] |

Evidence codes – TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence); Evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [13].

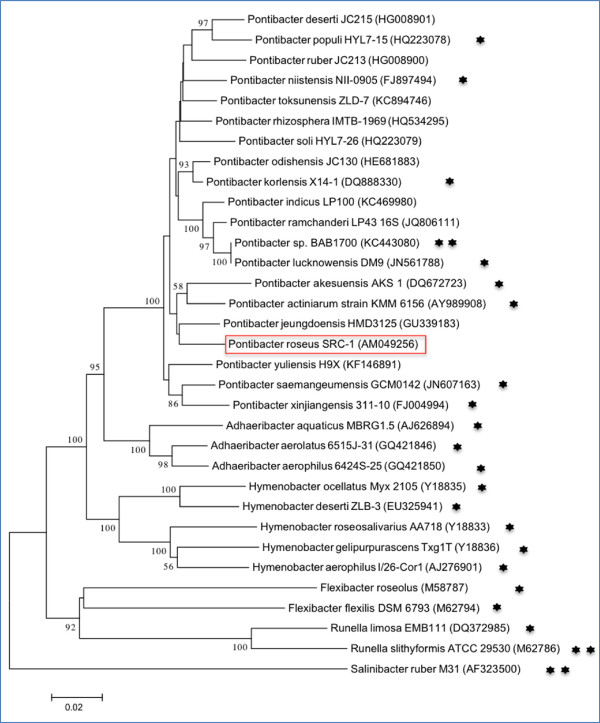

A representative genomic 16S rRNA sequence of Pontibacter roseus SRC-1T was compared with the May 2013; release 13_5 of Greengenes database [14] using NCBI BLAST under default values. The top 250 hits with an alignment length cut-off of 1000 bp were retained among which genomes belonging to genus Pontibacter were the most abundant (45.6%) followed by Adhaeribacter (35.6%), those assigned to the family Cytophagaceae but without a defined genus name (16.4%) and Hymenobacter (2.4%). Among samples with available metadata, approximately 61% of the above hits were from a soil environment, 11% were isolated from skin and approximately 9% from aquatic samples. This distribution reflects the wide range of habitats commonly observed among members of the genus Pontibacter and its phylogenetic neighbors, ranging from forest soil to desert, contaminated aquatic and soil environments, sediments and seawater among others [15-18]. Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of Pontibacter roseus SRC-1T in a 16S rRNA based tree.

Figure 1.

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, showing the relationships of Pontibacter roseus SRC-1Tto other published Pontibacter type strains and representative type strains of the family Cytophagaceae with Salinibacter ruber M31 as the outgroup. The neighbor joining [19] tree was constructed using MEGA v5.2.2 [20] based on the p-distance model with bootstrap values >50 (expressed as percentages of 1,000 replicates) shown at branch points. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [21] are labeled with one asterisk, while those with a published genome sequence is marked with two asterisks [16,22,23].

The predominant respiratory quinone for strain SRC-1T is menaquinone 7 (MK-7), consistent with other members of the Pontibacter genus. Short chain menaquinones with six or seven isoprene units are characteristic of the different genera within the aerobic members of the phylum Bacteroidetes. The primary whole-cell fatty acids are branched chain iso-C15 : 0 (14%), iso-C17 : 0 3-OH (14.7%) and summed feature 4 (34.9%, comprising of anteiso-C17 : 1 B and/or iso-C17 : 1 I, a pair of fatty acids that are grouped together for the purpose of evaluation by the Microbial Identification System(MIDI) as described earlier [24]) [2,3]. 2-OH Fatty acids are absent. The original paper describing P. roseus SRC-1T (as Effluviibacter roseus) [2] lists the polar lipids in strain SRC-1T being phosphatidylglycerol, diphosphatidylglycerol and an unknown phospholipid. This is in stark contrast to the known lipid profile of this evolutionary group where phosphatidylethanolamine is usually the sole major digylceride based phospholipid and other non-phosphate based lipids make up a significant proportion of the polar lipids. Accordingly, while genes for phosphatidylserine synthase and a decarboxylase to convert the serine to phosphatidylethanolamine could be detected, we did not find any evidence in P. roseus DSM 17521T genome to indicate that it produces the corresponding enzymes involved in the synthesis of phosphatidylglycerol or diphosphatidylglycerol. We therefore conclude that the original report on the lipid composition of strain SRC-1T is probably in error. It should be noted that the original publication did not provide images of the TLC plates allowing others to examine these data set [2].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position [25,26]. It is a part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Type Strains, KMG-I project [27], a follow-up of the GEBA project [28], which aims to increase the sequencing coverage of key reference microbial genomes and to generate a large genomic basis for the discovery of genes encoding novel enzymes [29]. KMG-I is a Genomic Standards Consortium project [30]. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database [21], the annotated genome is publicly available from the IMG Database [31] under the accession 2515154084, and the permanent draft genome sequence has been deposited at GenBank under accession number ARDO00000000. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) using state of the art technology [32]. The project information is briefly summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High-Quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Illumina Std shotgun library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina HiSeq 2000 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 122.8 × Illumina |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Velvet v. 1.1.04, ALLPATHS v. R41043 |

| MIGS-35 | GC Content | 52.65% |

| INSDC ID | ARDO01000000 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi11777 | |

| NCBI project ID | 169723 | |

| Release date | 08-13-2012 | |

| Database: IMG | 2515154084 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 17521 |

| Project relevance | GEBA-KMG, Tree of Life |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

Pontibacter roseus DSM 17521T, was grown aerobically in DSMZ medium 948 (Oxoid nutrient broth) [33] at 30°C. Genomic DNA was isolated using a Jetflex Genomic DNA Purification Kit (GENOMED 600100) following the standard protocol provided by the manufacturer with the following modifications: an additional incubation (60 min, 37°C) with 50 μl proteinase K and finally adding 200 μl protein precipitation buffer (PPT). DNA is available through the DNA Bank Network [34].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The draft genome of Pontibacter roseus DSM 17521T was generated at the DOE-JGI using the Illumina technology [35]. An Illumina Std shotgun library was constructed and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform which generated 12,071,874 reads totaling 1,810.8 Mbp. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI is publicly available [36]. All raw Illumina sequence data was passed through DUK, a filtering program developed at JGI, which removes known Illumina sequencing and library preparation artifacts. Following steps were then performed for assembly: (1) filtered Illumina reads were assembled using Velvet (version 1.1.04) [37], (2) 1–3 Kbp simulated paired end reads were created from Velvet contigs using wgsim [38], (3) Illumina reads were assembled with simulated read pairs using Allpaths–LG (version r41043) [39]. Parameters for assembly steps were: 1) Velvet (velveth: 63 –shortPaired and velvetg: -very clean yes –export- Filtered yes –min_contig_lgth 500 –scaffolding no –cov_cutoff 10) 2) wgsim (-e 0 –1 100 –2 100 –r 0 –R 0 –X 0) 3) Allpaths–LG (PrepareAllpathsInputs: PHRED_64 = 1 PLOIDY = 1 FRAG_COVERAGE = 125 JUMP_COVERAGE = 25 LONG_JUMP_COV = 50, RunAllpathsLG: THREADS = 8 RUN = std_shredpairs TARGETS = standard VAPI_WARN_ONLY = True.

OVERWRITE = True). The final draft assembly contained 12 scaffolds. The total size of the genome is 4.6 Mbp and the final assembly is based on 562.0 Mbp of Illumina data, which provides an average 122.8 × coverage of the genome. Additional information about the organism and its genome sequence and their associated MIGS record is provided in Additional file 1.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [40] as part of the JGI genome annotation pipeline [41], followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [42]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the NCBI nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. These data sources were combined to assert a product description for each predicted protein. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [43], RNAMMer [44], Rfam [45], TMHMM [46], SignalP [47] and CRT [48]. Additional gene functional annotation and comparative analysis were performed within the IMG platform [49].

Genome properties

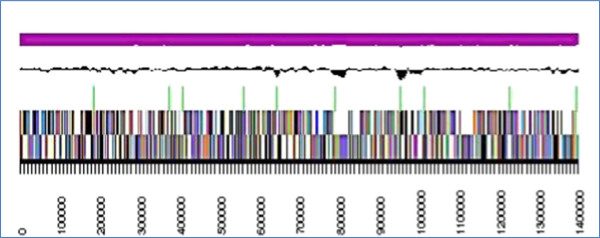

The assembly of the draft genome sequence consists of 12 scaffolds amounting to a 4,581,480 bp long chromosome with a GC content of approximately 53% (Table 3 and Figure 2). Of the 4,053 genes predicted, 4,003 were protein-coding genes along with 50 RNAs. The majority of protein-coding genes (69.4%) were assigned with a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins.

Table 3.

Genome statistics

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,581,480 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 3,984,478 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 2,411,942 |

| Total genes | 4,053 |

| RNA genes | 50 |

| rRNA operons | 1 |

| tRNA genes | 41 |

| Protein-coding genes | 4,003 |

| Pseudo genes | - |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,813 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 1,373 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,790 |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 3,062 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 611 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 997 |

Figure 2.

The graphical map of the largest scaffold of the genome. From bottom to the top: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNA green, rRNA red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew (purple/olive).

The functional distribution of genes assigned to COGs is shown in Table 4. A large percentage of the genes do not have an assigned COG category, are unknown or fall into general function prediction, which is typical for a newly sequenced organism that has not been well characterized yet.

Table 4.

Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % of total a | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 167 | 4.17 | Translation |

| A | 1 | 0.02 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 134 | 3.35 | Transcription |

| L | 105 | 2.62 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.02 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 27 | 0.67 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 60 | 1.50 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 94 | 2.35 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 229 | 5.72 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 11 | 0.27 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.00 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.00 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 30 | 0.75 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 94 | 2.35 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 153 | 3.82 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 126 | 3.15 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 203 | 5.07 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 65 | 1.62 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 99 | 2.47 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 96 | 2.40 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 149 | 3.72 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 69 | 1.72 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 328 | 8.19 | General function prediction only |

| S | 229 | 5.72 | Function unknown |

| - | 1790 | 44.72 | Not in COGs |

aThe total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

Insights from the genome sequence

Menaquinone biosynthesis

Respiratory lipoquinones such as ubiquinone and menaquinone are essential components of the electron transfer pathway in bacteria and archaea. While ubiquinones are limited to members of Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria [50], menaquinones have been found to be more widespread among prokaryotes [51,52], occurring in both aerobes and anaerobes. Menaquinone is a non-protein lipid-soluble redox component of the electron transport chain, which plays an important role in mediating electron transfer between membrane-bound protein complexes. The classical menaquinone biosynthesis pathway was studied primarily in Escherichia coli; more recently, an alternate pathway was identified in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) as well as in pathogens such as Helicobacter pylori and Campylobacter jejuni [53,54], aspects of which remain to be fully elucidated.

All identified species of the genus Pontibacter are known to possess menaquinone – 7 [16] which is the primary respiratory quinone in Pontibacter roseus SRC-1T [2]. Biosynthesis of menaquinone in this organism appears to occur via the classical pathway. Using comparative genomics we identified the genes possibly involved in menaquinone biosynthesis in P. roseus DSM 17521T (Table 5). Menaquinone biosynthesis genes have been extensively studied in E. coli where they are organized in an operon and in B. subtilis where gene neighborhood was helpful in identifying menC and menH genes [61]. However, the P. roseus genes seem to be spread across its chromosome. It is well known that conservation of gene order in bacteria can be disrupted during the course of evolution [62]. For example, isolated genes belonging to the menaquinone biosynthesis pathway leading to phylloquinione biosynthesis were identified in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 through sequence similarity with E. coli followed by transposon mutagenesis [63,64]. As more genomes become available, these aspects can be investigated in greater detail.

Table 5.

Predicted menaquinone biosynthesis genes in Pontibacter roseus DSM 17521 T

| IMG GeneID | IMG description | Identity to characterized proteins | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2515478196 | isochorismate synthases | 28% identity to E. coli MenF | [55] |

| 2515478195 | 2-succinyl-5-enolpyruvyl-6-hydroxy-3-cyclohexene-1-carboxylic-acid synthase | 30% identity to B. subtilis MenD | [56] |

| 2515478193 | Acyl-CoA synthetases | 26% identity to E. coli MenE | [57] |

| 2515478204 | naphthoate synthase | 52% identity to E. coli MenB | [58] |

| 2515479036 | 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoate octaprenyltransferase | 31% identity to E. coli MenA | [59] |

| 2515480441 | muconate and chloromuconate cycloisomerases | 48% identity with muconate cycloisomerase 1 of Pseudomonas putida | [60] |

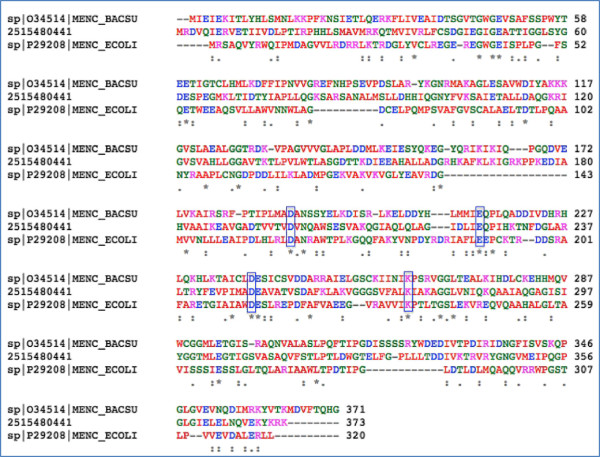

An o-succinylbenzoate synthase that is part of the menaquinone biosynthetic pathway encoded by the menC gene in E. coli and B. subtilis is missing from the Pontibacter roseus genome. A gene annotated as muconate cycloisomerase in Pontibacter roseus DSM 17521T (IMG geneID 2515480441) may perform this function. It contains conserved domains belonging to Muconate Lactonizing Enzyme subgroup of the enolase superfamily. Sequence similarity between different members of the enolase superfamily is typically less than 25% [65]. Even though they possess similar structural scaffolds, they are known to have evolved significantly such that their functional role cannot be easily assigned through sequence similarity alone [66]. For example, B. subtilis menC was initially annotated as ‘similar to muconate cycloisomerase of Pseudomonas putida’ and ‘N-acylamino acid racemase’ but was later corrected to be OSBS [61]. The P. roseus gene shares protein level identity of 48% with muconate cycloisomerase 1 of Pseudomonas putida [60] and approximately 23% and 17% with E. coli and B. subtilis MenC respectively [61,67]. Multiple sequence alignment (Figure 3) of the above three genes reveal conservation of Asp161, Glu190, Asp213 and Lys235 (boxes in Figure 3) which have been predicted to be essential for OSBS in E. coli and other members of the enzyme family [65]. We thereby propose that IMG 2515480441 performs the function of MenC in P. roseus DSM 17521T.

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of MenC from E. coli , B. subtilis and predicted MenC in P. roseus (IMG 2515480441) showing conserved amino acids predicted to be essential for proper functioning of the enzyme.

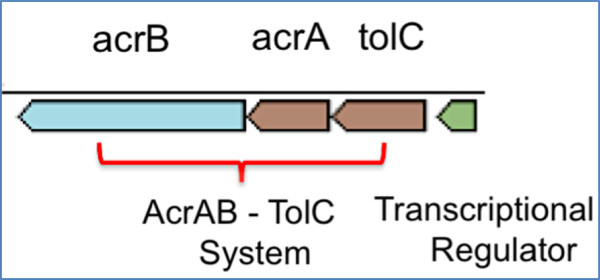

Multidrug resistance (MDR) efflux pump

Resistance to antibiotic drugs is one of the major public health concerns of today as highlighted in the recent report by the CDC [68]. Among several other mechanisms, multidrug resistance efflux pumps play a very important role in conferring decreased susceptibility to antibiotics in bacteria by transporting drugs across the bacterial membrane and preventing intracellular accumulation [69]. AcrAB-TolC is one of the most studied MDR efflux systems in Gram-negative bacteria. It is comprised of an inner membrane efflux transporter (AcrB), a linker protein (AcrA) and an outer membrane protein (TolC), which interacts with AcrA and AcrB and forms a multifunctional channel that is essential to pump cellular products out of the cell [69,70]. Previous reports have identified gene clusters predicted to confer antibiotic resistance in members of Pontibacter [16]. Applying comparative analysis with characterized proteins, we identified a set of genes (IMG ID 2515478940–43) that may function as a multi-drug resistance efflux pump in P. roseus DSM 17521T (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Predicted MDR efflux system in P. roseus with AcrAB-TolC along with a transcriptional regulator.

P. roseus 2515478940 is 37% identical to E. coli multidrug efflux pump subunit AcrB [71]; 2515478941 shares 28% identity to E. coli AcrA [72] while 2515478942 is 20% identical to E. coli outer membrane protein TolC [73]. Additionally, there is a transcriptional repressor (2515478943) upstream of TolC which shares 25% protein level identity to HTH-type transcriptional repressor Bm3R1 [74] from Bacillus megaterium and may act as a regulator of the MDR transport system in P. roseus DSM 17521T.

Conclusions

Members of the genus Pontibacter occupy a unique phylogenetic niche within the phylum Bacteroidetes. As of writing, this genome report is only the second for the entire genus. In addition to a detailed analysis of the P. roseus genome we highlight some of the key functional characteristics of the organism and summarize the genes encoding enzymes leading to the biosynthesis of menaquinone, the primary respiratory quinone for majority of the species of the genus.

Abbreviations

KMG: One thousand microbial genomes; OSBS: o-succinylbenzoate synthase; MDR: Multi-Drug Resistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SM, BJT, SS, MG, HPK, NCK and AP drafted the manuscript. AL, NS, J-FC, JH, TBKR, MH, NI, NM, AC, KP and TW sequenced, assembled and annotated the genome. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Associated MIGS record.

Contributor Information

Supratim Mukherjee, Email: supratimmukherjee@lbl.gov.

Alla Lapidus, Email: ALapidus@lbl.gov.

Nicole Shapiro, Email: nrshapiro@lbl.gov.

Jan-Fang Cheng, Email: jfcheng@lbl.gov.

James Han, Email: jkhan@lbl.gov.

TBK Reddy, Email: TBReddy@lbl.gov.

Marcel Huntemann, Email: mhuntemann@lbl.gov.

Natalia Ivanova, Email: nnivanova@lbl.gov.

Natalia Mikhailova, Email: nmikhailova@lbl.gov.

Amy Chen, Email: imachen@lbl.gov.

Krishna Palaniappan, Email: kpalaniappan@lbl.gov.

Stefan Spring, Email: Stefan.Spring@dsmz.de.

Markus Göker, Email: Markus.Goker@dsmz.de.

Victor Markowitz, Email: vmmarkowitz@lbl.gov.

Tanja Woyke, Email: twoyke@lbl.gov.

Brian J Tindall, Email: Brian.Tindall@dsmz.de.

Hans-Peter Klenk, Email: Hans-Peter.Klenk@dsmz.de.

Nikos C Kyrpides, Email: nckyrpides@lbl.gov.

Amrita Pati, Email: apati@lbl.gov.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Andrea Schütze for growing P. roseus DSM 17521T cultures and Evelyne-Marie Brambilla for DNA extraction and quality control (both at the DSMZ). The work conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. A. L. was supported in part by Russian Ministry of Science Mega-grant no.11.G34.31.0068 (PI. Dr. Stephen J O’Brien).

References

- Nedashkovskaya OI, Kim SB, Suzuki M, Shevchenko LS, Lee MS, Lee KH, Park MS, Frolova GM, Oh HW, Bae KS. et al. Pontibacter actiniarum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the phylum “Bacteroidetes”, and proposal of Reichenbachiella gen. nov. as a replacement for the illegitimate prokaryotic generic name Reichenbachia Nedashkovskaya et al. 2003. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:2583–8. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63819-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh K, Mayilraj S, Chakrabarti T. Effluviibacter roseus gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from muddy water, belonging to the family ‘Flexibacteraceae.’. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:1703–7. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang K, Cai F, Zhang L, Tang Y, Dai J, Fang C. Pontibacter xinjiangensis sp. nov., in the phylum “ Bacteroidetes ”, and reclassification of [Effluviibacter] roseus as Pontibacter roseus comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:99–103. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.011395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatutsova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV. et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field D, Amaral-Zettler L, Cochrane G, Cole JR, Dawyndt P, Garrity GM, Gilbert J, Glöckner FO, Hirschman L, Karsch-Mizrachi I. et al. The genomic standards consortium. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87:4576–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg N, Ludwig W, Euzéby J, Whitman W, Phylum XIV. In: Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition vol. 4 (The Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes, Tenericutes (Mollicutes), Acidobacteria, Fibrobacteres, Fusobacteria, Dictyoglomi, Gemmatimonadetes, Lentisphaerae, Verrucomicrobia, Chlamydiae, and Planctomycetes) Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, Ward NL, Ludwig W, Whitman WB, editor. Vol. 4. New York: Springer; 2010. Bacteroidetes phyl. nov; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ohren A, Garrity GM. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:1–4. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Class IV. In: Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition, vol. 4 (The Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes, Tenericutes (Mollicutes), Acidobacteria, Fibrobacteres, Fusobacteria, Dictyoglomi, Gemmatimonadetes, Lentisphaerae, Verrucomicrobia, Chlamydiae, and Planctomycetes.) Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, Ward NL, Ludwig W, Whitman WB, editor. New York: Springer; 2010. Cytophagia class. nov; p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- Skerman VBD, McGOWAN V, Sneath PHA. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbetter E, Order II. In: Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. 8. Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE, editor. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Co; 1974. Cytophagales nomen novum; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- Stanier RY. Studies on the Cytophagas. J Bacteriol. 1940;40:619–35. doi: 10.1128/jb.40.5.619-635.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Anderson GL. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–72. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Garg N, Lata P, Kumar R, Negi V, Vikram S, Lal R. Pontibacter indicus sp. nov., isolated from hexachlorocyclohexane-contaminated soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:254–9. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.055319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi MN, Sharma AC, Pandya RV, Patel RP, Saiyed ZM, Saxena AK, Bagatharia SB. Draft Genome Sequence of Pontibacter sp. nov. BAB1700, a Halotolerant, Industrially Important Bacterium. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:6329–30. doi: 10.1128/JB.01550-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Wang X, Liu H, Zhang KY, Zhang YQ, Lai R, Li WJ. Pontibacter akesuensis sp. nov., isolated from a desert soil in China. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:321–5. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64716-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedashkovskaya OI, Kim SB, Suzuki M, Shevchenko LS, Lee MS, Lee KH, Park MS, Frolova GM, Oh HW, Bae KS. et al. Pontibacter actiniarum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the phylum “Bacteroidetes”, and proposal of Reichenbachiella gen. nov. as a replacement for the illegitimate prokaryotic generic name Reichenbachia Nedashkovskaya et al. 2003. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:2583–8. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63819-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–25. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani I, Liolios K, Jansson J, Chen IA, Smirnova T, Nosrat B, Markowitz V, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v. 4: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D571–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland A, Zhang X, Misra M, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Lucas S, Deshpande S, Cheng JF, Tapia R, Goodwin L. et al. Complete genome sequence of the aquatic bacterium Runella slithyformis type strain (LSU 4T) Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;6 doi: 10.4056/sigs.2475579. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22768358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongodin EF, Nelson KE, Daugherty S, DeBoy RT, Wister J, Khouri H, Weidman J, Walsh DA, Papke RT, Sanchez Perez G. et al. The genome of Salinibacter ruber: convergence and gene exchange among hyperhalophilic bacteria and Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18147–18152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509073102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey KK, Mayilraj S, Chakrabarti T. Pseudomonas indica sp. nov., a novel butane-utilizing species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:1559–67. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.01943-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göker M, Klenk H-P. Phylogeny-driven target selection for large-scale genome-sequencing (and other) projects. Stand Genomic Sci. 2013;8:360–74. doi: 10.4056/sigs.3446951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenk H-P, Göker M. En route to a genome-based classification of Archaea and Bacteria? Syst Appl Microbiol. 2010;33:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrpides NC, Woyke T, Eisen JA, Garrity GM, Lilburn TG, Beck BJ, Whitman WB, Hugenholtz P, Klenk HP. Genomic encyclopedia of type strains, phase I: the one thousand microbial genomes (KMG-I) project. Stand Genomic Sci. 2014;9:1278–84. doi: 10.4056/sigs.5068949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ. et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature. 2009;462:1056–60. doi: 10.1038/nature08656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao H, Froula J, Du C, Kim TW, Hawley ER, Bauer S, Wang Z, Ivanova NN, Clark DS, Klenk HP, Hess M. Identification of novel biomass-degrading enzymes from genomic dark matter: Populating genomic sequence space with functional annotation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:1550–65. doi: 10.1002/bit.25250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field D, Sterk P, Kottmann R, Smet WD, Amaral-Zettler L, Cochrane G, Davies N, Dawyndt P, Garrity GM, Gilbert JA. et al. Genomic standards consortium projects. Stand Genomic Sci. 2014;9:599–601. doi: 10.4056/sigs.5559608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz VM, Chen I-MA, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Pillay M, Ratner A, Huang J, Woyke T, Huntemann M. et al. IMG 4 version of the integrated microbial genomes comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D560–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavromatis K, Land ML, Brettin TS, Quest DJ, Copeland A, Clum A, Goodwin L, Woyke T, Lapidus A, Klenk HP. et al. The fast changing landscape of sequencing technologies and their impact on microbial genome assemblies and annotation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List of growth media used at DSMZ. http://www.dsmz.de/catalogues/catalogue-microorganisms/culture-technology/list-of-media-for-microorganisms.html.

- Gemeinholzer B, Dröge G, Zetzsche H, Haszprunar, Klenk HP, Güntsch A, Berendsohn WG, Wägele JW. The DNA bank network: the start from a German initiative. Biopreserv Biobank. 2011;9:51–5. doi: 10.1089/bio.2010.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S. Solexa Ltd. Pharmacogenomics. 2004;5:433–8. doi: 10.1517/14622416.5.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOE Joint Genome Institute. A DOE office of science user facility of Lawrence Berkeley national laboratory. DOE Jt Genome Inst. http://jgi.doe.gov.

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wgsim. Available at: https://github.com/lh3/wgsim.

- Gnerre S, Maccallum I, Przybylski D, Ribeiro FJ, Burton JN, Walker BJ, Sharpe T, Hall G, Shea TP, Sykes S. et al. High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1513–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017351108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt D, Chen G-L, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen I-MA, Szeto E, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The DOE-JGI standard operating procedure for the annotations of microbial genomes. Stand Genomic Sci. 2009;1:63–7. doi: 10.4056/sigs.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pati A, Ivanova NN, Mikhailova N, Ovchinnikova G, Hooper S, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: a gene prediction improvement pipeline for prokaryotic genomes. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:455–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Staerfeldt H-H, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:439–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–80. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland C, Ramsey TL, Sabree F, Lowe M, Brown K, Kyrpides NC, Hugenholtz P. CRISPR recognition tool (CRT): a tool for automatic detection of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:209. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen I-MA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2009;25:2271–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindall BJ, Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual. Netherlands: Springer; 2004. Section 4 Update: Respiratory Lipoquinones as Biomarkers; pp. 2907–28. [Google Scholar]

- Collins MD, Jones D. Distribution of isoprenoid quinone structural types in bacteria and their taxonomic implication. Microbiol Rev. 1981;45:316–54. doi: 10.1128/mr.45.2.316-354.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi X-Y, Yao J-C, Tang S-K, Huang Y, Li H-W, Li W-J. The futalosine pathway played an important role in menaquinone biosynthesis during early prokaryote evolution. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:149–60. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsuka T, Furihata K, Ishikawa J, Yamashita H, Itoh N, Seto H, Dairi T. An alternative menaquinone biosynthetic pathway operating in microorganisms. Science. 2008;321:1670–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1160446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dairi T. Menaquinone biosyntheses in microorganisms. Methods Enzymol. 2012;515:107–22. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394290-6.00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daruwala R, Kwon O, Meganathan R, Hudspeth ME. A new isochorismate synthase specifically involved in menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis encoded by the menF gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;140:159–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B, Hill K, Miller P, Driscoll J, Taber H. Structural organization of a Bacillus subtilis operon encoding menaquinone biosynthetic enzymes. Gene. 1995;167:105–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V, Hudspeth ME, Meganathan R. Menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis: localization and characterization of the menE gene from Escherichia coli. Gene. 1996;168:43–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V, Suvarna K, Meganathan R, Hudspeth ME. Menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis: nucleotide sequence and expression of the menB gene from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5057–62. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5057-5062.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvarna K, Stevenson D, Meganathan R, Hudspeth ME. Menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis: localization and characterization of the menA gene from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2782–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2782-2787.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich TL, Frantz B, Gill JF, Kilbane JJ, Chakrabarty AM. Cloning and complete nucleotide sequence determination of the catB gene encoding cis, cis-muconate lactonizing enzyme. Gene. 1987;52:185–95. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90045-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer DR, Garrett JB, Sharma V, Meganathan R, Babbitt PC, Gerlt JA. Unexpected divergence of enzyme function and sequence: “N-acylamino acid racemase” is o-succinylbenzoate synthase. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1999;38:4252–8. doi: 10.1021/bi990140p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Takemoto K, Mori H, Gojobori T. Evolutionary instability of operon structures disclosed by sequence comparisons of complete microbial genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:332–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TW, Shen G, Zybailov B, Kolling D, Reategui R, Beauparlant S, Vassiliev IR, Bryant DA, Jones AD, Beauparlant S. et al. Recruitment of a Foreign Quinone into the A1 Site of Photosystem I I. Genetic and physiological characterization of phylloquinone biosynthetic pathway mutants in synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8523–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Laborde SM, Frankel LK, Bricker TM. Four novel genes required for optimal photoautotrophic growth of the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC 6803 identified by in vitro transposon mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:875–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.875-879.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson TB, Garrett JB, Taylor EA, Meganathan R, Gerlt JA, Rayment I. Evolution of enzymatic activity in the enolase superfamily: structure of o-succinylbenzoate synthase from escherichia coli in complex with Mg2+ and o-succinylbenzoate. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2000;39:10662–76. doi: 10.1021/bi000855o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt JA, Babbitt PC. Can sequence determine function? Genome Biol. 2000;1:REVIEWS0005. doi: 10.1186/gb-2000-1-5-reviews0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V, Meganathan R, Hudspeth ME. Menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis: cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the menC gene from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4917–21. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4917-4921.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/

- Piddock LJV. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps? not just for resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:629–36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros M, Dupont M, Rodrigues L, Couto I, Davin-Regli A, Martins M, Pagès JM, Amaral L. Antibiotic stress. Genetic response and altered permeability of E. coli. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu EW, Aires JR, Nikaido H. AcrB multidrug efflux pump of Escherichia coli: composite substrate-binding cavity of exceptional flexibility generates its extremely wide substrate specificity. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5657–64. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.19.5657-5664.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Cook DN, Alberti M, Pon NG, Nikaido H, Hearst JE. Molecular cloning and characterization of acrA and acrE genes of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6299–313. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6299-6313.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koronakis V, Sharff A, Koronakis E, Luisi B, Hughes C. Crystal structure of the bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature. 2000;405:914–9. doi: 10.1038/35016007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GC, Fulco AJ. Barbiturate-mediated regulation of expression of the cytochrome P450BM-3 gene of Bacillus megaterium by Bm3R1 protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5515–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Associated MIGS record.