Abstract

Entorrhiza is a small fungal genus comprising 14 species that all cause galls on roots of Cyperaceae and Juncaceae. Although this genus was established 130 years ago, crucial questions on the phylogenetic relationships and biology of this enigmatic taxon are still unanswered. In order to infer a robust hypothesis about the phylogenetic position of Entorrhiza and to evaluate evolutionary trends, multiple gene sequences and morphological characteristics of Entorrhiza were analyzed and compared with respective findings in Fungi. In our comprehensive five-gene analyses Entorrhiza appeared as a highly supported monophyletic lineage representing the sister group to the rest of the Dikarya, a phylogenetic placement that received but moderate maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony bootstrap support. An alternative maximum likelihood tree with the constraint that Entorrhiza forms a monophyletic group with Basidiomycota could not be rejected. According to the first phylogenetic hypothesis, the teliospore tetrads of Entorrhiza represent the prototype of the dikaryan meiosporangium. The alternative hypothesis is supported by similarities in septal pore structure, cell wall and spindle pole bodies. Based on the isolated phylogenetic position of Entorrhiza and its peculiar combination of features related to ultrastructure and reproduction mode, we propose a new phylum Entorrhizomycota, for the genus Entorrhiza, which represents an apparently widespread group of inconspicuous fungi.

Introduction

The genus Entorrhiza was erected by Weber [1] to describe fungi causing galls on root tips of members of Cyperaceae and Juncaceae (Fig 1). Currently, this small and morphologically uniform genus comprises 14 known species, nine species of which–including the type species E. cypericola–occur exclusively in roots of members of Cyperaceae (Carex, Cyperus, Eleocharis, Isolepis, Scirpus), and four occur on members of Juncaceae (Juncus). Only E. caricicola was reported from both Cyperaceae (Carex, Eleocharis) and Juncaceae (Juncus) families [2]. Within the galls Entorrhiza forms regularly septate clampless hyphae that are coiled in living host cells, where they terminate with globose cells that detach from the hyphae and become thick-walled teliospores [3–4]. Because of the uniform morphology and the restricted host range it was suggested that this genus represents a monophyletic group [5].

Fig 1. Portion of a tussock of Juncus articulatus with root galls caused by Entorrhiza casparyana (arrows).

Note that the older segments of the galls are brown-colored while younger parts are whitish (tips).

As studied in Entorrhiza casparyana, the exosporium of the teliospores is probably formed by the host [6]. The septa have dolipores [4], [7–8]. After a resting period of some months teliospores germinate internally by becoming regularly four-celled “phragmobasidia” [8–10]. Deml and Oberwinkler [4], having used incorrectly labelled preparations for microscopy, illustrated a clamped hypha and a Tilletia-like basidium for E. casparyana [11].

Entorrhiza had uncertain positions in recently published phylogenetic studies [12–14]. These studies suggested two possible phylogenetic placements for Entorrhiza, either as a sister group of all other Ustilaginomycotina [7–8], [12], [15], or as a sister group of the Basidiomycota [13–14]. However, so far only rDNA genes have been used to infer phylogenetic hypotheses.

In order to achieve a robust estimate for the phylogenetic position of Entorrhiza and to evaluate evolutionary trends, we followed two strategies: First, we analyzed nucleotide sequences of the rDNA coding for the 18S, 5.8S and 28S ribosomal subunits together with amino acid sequences of the rpb1 and rpb2 genes of E. aschersoniana (on Juncus bufonius, Juncaceae), E. casparyana (on Juncus articulatus, Juncaceae) and E. parvula (on Eleocharis parvula, Cyperaceae), together with a representative dataset of the Fungi. Second, we compared morphological characteristics of Entorrhiza with homologous structures in other fungal groups.

Material and Methods

Ethics statement

The plant and fungal specimen used in this study, as well as the sampling sites, were not protected and therefore no specific permits were requested for sampling.

Molecular phylogenetic analyses

The following specimens of Entorrhiza were used to obtain new sequences (see Table 1): E. aschersoniana on Juncus bufonius, Costa Rica, Prov. Cartago, Irazú, entrance area of the park, 13 Oct 1996, leg. M. Piepenbring, MP2230; E. aschersoniana on J. bufonius, Poland, Malopolska Province: Markowa, ca. 60 km SW of Krakow, 49°09'10''N 9°59'48''E, 830 m above sea level (a.s.l.), 8 Sept 2006, leg. J. and M. Piątek, KRAM-56778; E. casparyana on J. articulatus, Australia, Tasmania, south of Ben Lomond National Park, road B 42, near Rosarden, 41°37'08.8"S 147°52'07.8"E, 17 March 1996, leg. C. and K. Vánky, HUV 17623; E. casparyana on J. articulatus, Germany, Baden-Württemberg, Triensbach, Reusenberg, 49°09'10.3"N 9°59'48.8"E, 2 Oct 2007, leg. R. Bauer, RB 3117; and E. parvula on Eleocharis parvula, France, Gironde, Bassin d’Arcachon, Arès, 44°47'00"N 1°09'02"W, 25 July 2014, leg. M. Lutz and M. Piątek, TUB 021488. For E. casparyana, we separately amplified rpb1 and rpb2 from the collections RB 941, RB 3117 and RB 3200, which sequences proved to be identical.

Table 1. List of species and GenBank accession numbers used for the combined multiple gene analysis (see Fig 2).

Accession numbers of sequences generated in this study are indicated by boldface. Voucher numbers can be inferred from the respective GenBank accessions.

We assembled a dataset comprising ribosomal (18S+5.8S+28S) and protein-coding (rpb1+rpb2) sequences of Entorrhiza and 51 samples representing the main clades of the Fungi, see Table 1. Our dataset was complemented with DNA sequences downloaded from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), mainly from studies by James et al. [16] and Liu et al. [17]. The final alignment has been deposited in TreeBASE under submission ID S15778.

Genomic DNA was extracted from root galls of Entorrhiza aschersoniana, E. casparyana, and E. parvula (one gall per species) and from basidiocarps or strains of additional fungi using a DNAeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or an InnuPREP Plant DNA Kit (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany) according to the manufacturers protocols. Galls were washed carefully with tap water and rinsed several times in sterile double-distilled water. All fungal samples were ground in liquid nitrogen, suspended in 400 μl extraction buffer and incubated for 40 min at 65°C. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers RPB1-A and RPB1-C [18] were used to target domains A–C of rpb1, and rpb2 was amplified with the primer pair RPB2-5F and RPB2-11bR [19]. PCRs were performed using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Finnzymes Oy, Vantaa, Finland), following the protocol recommended by the manufacturer with annealing temperatures of approximately 5°C above the mean primer melting temperatures, for 30 cycles. Amplicons of positive PCRs were purified using ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH, USA), and diluted 1:20. Sequencing of rpb1 and rpb2 genes was carried out using amplification primers and with additional primers as described in Liu et al. [17]. Cycle sequencing was accomplished using a 1:6 diluted BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed on an ABI Prism 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Forward and reverse sequence chromatograms were checked for accuracy and edited using Sequencher v. 4.1 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Nucleotide sequences of rpb1 and rpb2 were aligned separately in DIALIGN2-2 [20] with assessments of both nucleotide and amino acid homology (option-nt). From aligned datasets, exon C in rpb1 and exons 4 and 5 in rpb2 were identified via comparisons with annotated coding sequences of Phragmidium (EF014377 and AY485630) in Se-Al v. 2.0a11 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/seal). In addition, for the identification of introns we used annotated sequences of Neolecta vitellina (EF014375) and Taphrina deformans (EF014374) from GenBank, and the GT-AG border motifs [21]. The final rpb1 and rpb2 alignments had lengths of 134 and 595 amino acids, respectively. Ribosomal DNA sequences were aligned with the MAFFT server (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/index.html) [22] separately for the 18S, 5.8S, and 28S regions, using the E-INS-i option. Ambiguously aligned regions were then removed with Gblocks [23], with gaps allowed at an alignment position when present in more than half of the sequences, a minimum block length of five, a minimum number of sequences for a conserved position or a flanking position of 29, and a maximum number of contiguous nonconserved positions of eight. Alignment length for the trimmed 18S, 5.8S, and 28S datasets were 1596, 155, and 1167 nucleotides, respectively. The single-gene alignments were then concatenated into a single mixed DNA / amino acid dataset of a total of 3,647 characters.

For phylogenetic analysis of this dataset we used maximum likelihood (ML), Bayesian MCMC (BI), and maximum parsimony (MP) based approaches. RAxML v. 8.0.24 [24] was employed in a parallelized version available at the CIPRES portal (http://www.phylo.org), using the GTR model of DNA substitution and starting trees inferred from 1,000 rapid bootstrap analyses [25] in a heuristic search for the tree with the highest likelihood (-f a option). For the rpb1/rpb2 amino acid data, the LG model [26] was chosen using the model selection function of RAxML (AUTO option). To model rate heterogeneity, Gamma-distributed substitution rates were assumed both for the rDNA and the protein alignment parts. RAxML was also employed to infer ML trees for all single-tree alignments (with settings as described above).

Second, we analyzed the datasets using BI as implemented in MrBayes v. 3.2.2 [27]. For each dataset two parallel runs were performed, each over 5 million generations, with a sample frequency of 100 and a burn-in percentage of 20%, integrating the stored trees from the two parallel runs in a single majority-rule consensus. For the rDNA parts we used the GTR model, and for the amino acid parts we allowed sampling of the available amino acid substitution models during the MCMC process (aamodelpr = mixed); rate heterogeneity was modelled with unlinked Gamma distributions. We also unlinked all substitution models, state frequencies, rate multipliers, and branch lengths for the partition subsets.

Third, we did MP bootstrap analyses in PAUP* v. 4a136 [28] with 1000 bootstrap replicates. In each bootstrap replicate we performed ten heuristic searches, with starting trees obtained by subsequently adding sequences in random order and using TBR branch swapping (multrees option switched on and steepest descent option switched off). Gaps were treated as missing data.

We also did an ML analysis in RAxML to search for the best tree with the constraint that the union of Basidiomycota and Entorrhiza is monophyletic (with additional settings as described above). A Shimodaira-Hasegawa (SH) test [29] was performed to test whether this tree was significantly worse than the overall best tree.

Finally, we calculated internode certainty (ICA) and tree certainty (TCA) values for the multigene and the single-gene ML trees [30]. ICA is a measure of the amount of information that relates to a branch and is calculated from the frequency distribution of the relevant bipartitions for this branch in the bootstrap trees, i.e., from the frequency of the bipartition represented by this branch (which equals the bootstrap value) and the frequencies of those bipartitions present in the bootstrap trees that are in conflict with this branch [30]. TCA is the average of all ICA values in a tree and facilitates the comparison of different trees with respect to their mean internode certainty.

Microscopy

For teliospore germination the following specimen was used: Entorrhiza casparyana on Juncus articulatus, Germany, Baden-Württemberg, Triensbach, Reusenberg, 49°09'10.3"N 9°59'48.8"E, 10 Oct 1988, leg. R. Bauer 942. Galls were placed in water in petri dishes, incubated at 7°C and examined weekly.

For light microscopy (LM), the following specimens were used: Entorrhiza casparyana on Juncus articulatus, Switzerland, near Preda, Albuda pass, 46°35'03.5"N 9°51'11.9"E, 1976, leg. G. Deml and E. casparyana on J. articulatus R. Bauer 942 (see above). Living material was examined with an Axioplan microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using bright field, phase contrast, or Nomarski interference contrast optics. For nuclear staining, material was dried on slides for 10 min at room temperature, then fixed with a 3:1 mixture of 92% ethanol and acetic acid for 30 min. After rinsing the material several times with water, it was hydrolysed in 60°C HCl (1N) for 7 min, rinsed again in one change of water and five changes of phosphate buffer (pH 7), then stained for 2 h in Giemsa stock solution and phosphate buffer (1:9, v/v). It was then rinsed once more in phosphate buffer, dipped in water, and mounted with a cover glass.

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) Entorrhiza casparyana on Juncus articulatus R. Bauer 942 was used (see above). Galls were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) at room temperature. After six transfers in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer the samples were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer for 1 h in the dark. The samples were washed in distilled water and then stained in 1% aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 h in the dark. After five washes in distilled water, the samples were dehydrated in a graded series of acetone, using 10 min-changes at 25%, 50%, 70%, 95%, and three times at 100%. Samples were embedded in Spurr’s plastic and then cut with a diamond knife-equipped Reichert-Jung Ultracut E microtome and collected on formvar-coated slot grids. They were post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate at room temperature for 5 min, and then washed with distilled water. Samples were examined with a Zeiss transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the following specimen was used: Entorrhiza casparyana on Juncus articulatus, Russia, Karelia, Kiwatsch, 62°12'02.2"N 34°16'07.4"E, August 2010, leg. D. Begerow 1234. A gall was fixed in 5% formalin – 5% acetic acid – 90% alcohol v/v (FAA), washed with deionised water (3–10 min), dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series, transferred to formaldehyde dimethyl acetal (FDA) for 24 h [31], critical-point dried, split with a razor blade in two halves and sputter-coated with gold for 220 s. The material was examined with a DSM 950 (Zeiss) at 15 kV and the results were documented using Digital Image Processing Software v. 2.2 (DIPS, Leipzig, Germany).

Nomenclature

The electronic version of this article in Portable Document Format (PDF) in a work with an ISSN or ISBN will represent a published work according to the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, and hence the new names contained in the electronic publication of a PLoS ONE article are effectively published under that Code from the electronic edition alone, so there is no longer any need to provide printed copies. In addition, the taxon species name contained in this work was submitted to MycoBank, from where they will be made available to the Global Names Index. The MycoBank number can be resolved and the associated information viewed through any standard web browser by appending the MycoBank number contained in this publication to the prefix www.mycobank.org/MB. The online version of this work is archived and available from the following digital repositories: PubMed Central, LOCKSS.

Results

Molecular phylogenetic analysis

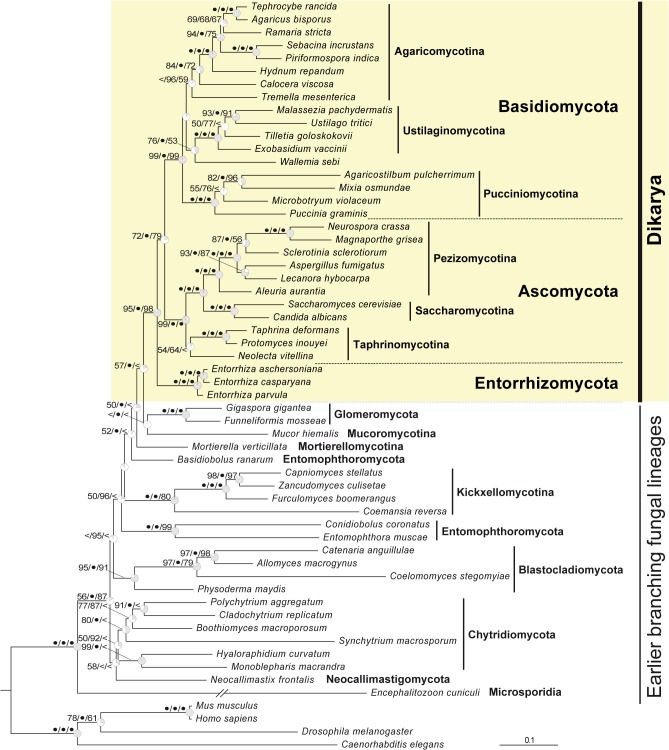

The phylogenetic position of the genus Entorrhiza derived from a combined dataset of rDNA (18S, 5.8S and 28S) and amino acid (RPB1 and RPB2) sequences is shown in Fig 2. Entorrhiza aschersoniana, E. casparyana and E. parvula formed a highly supported monophyletic group in all phylogenetic analyses. In the ML analysis this group appeared as the most basal group of the Dikarya, a position which received 72% bootstrap support in ML and 79% in MP analysis, and a BI support of 100%. However, the branch supporting the monophyletic union of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota (without Entorrhiza) received an ICA value as low as 0.197, which indicates a considerable frequency of conflicting bipartitions in the set of the ML bootstrap trees. In the best tree found in the ML analysis under the constraint that Basidiomycota plus Entorrhiza is monophyletic, Entorrhiza was the sister group to the Basidiomycota (not shown). In the SH test this tree was not significantly worse than the overall best tree found (shown in Fig 2) at a significance level of p = 0.05.

Fig 2. Maximum likelihood tree showing the phylogenetic position of the genus Entorrhiza within the kingdom Fungi derived from a combined dataset of rDNA (18S, 5.8S and 28S) and amino acid (RPB1 and RPB2) sequences.

Branch support is given as maximum likelihood bootstrap percentage (1,000 replicates) / Bayesian posterior probability (consensus of two independent MCMC processes, each with four chains over five million generations) / maximum parsimony bootstrap (1,000 replicates). Values of 100% are designated with bullets, values below 50% are omitted or designated by <. Grey sectors in the clock symbols illustrate internode confidence values (ICA [30]) of the supporting branch; counterclockwise orientation designates a negative ICA value, i.e., an instance where a conflicting bipartition occurs more frequently in the bootstrap trees than the bipartition defined by this branch. The tree was rooted with the Metazoa branch. The Encephalitozoon branch was scaled with a factor of 0.5 for graphical reasons. For GenBank accession numbers see Table 1.

TCA values for the single-gene ML trees were 0.37 (18S), 0.34 (28S), 0.01 (5.8S), 0.24 (rpb1), and 0.49 (rpb2). In the ML tree for the gene with the highest TCA value (rpb2) Entorrhiza appeared as the most basal group in the Dikarya, and the union of Basidiomycota (without Entorrhiza) and Ascomycota received an ICA value of 0.534 (not shown).

Backbone relationships of the earlier diverged fungal lineages were poorly resolved, as indicated by low bootstrap values and low or even negative ICA values (Fig 2).

Morphology

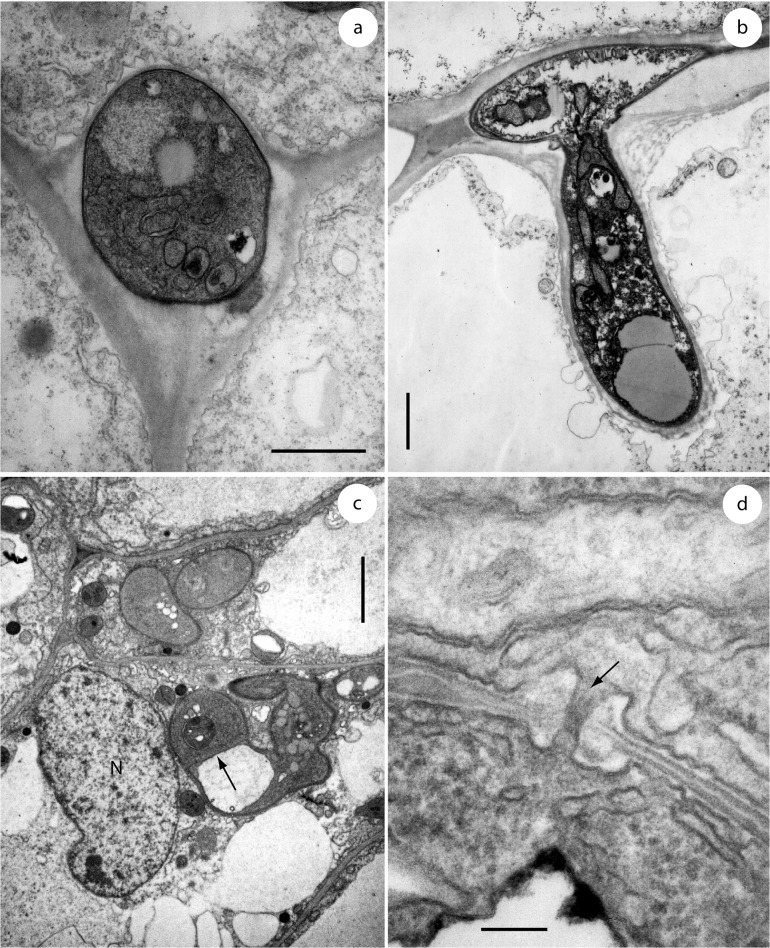

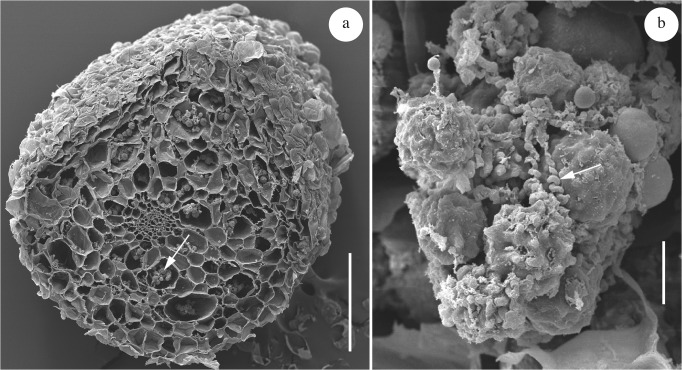

Entorrhiza casparyana caused galls on roots of Juncus articulatus (Fig 1). Our morphological analyses allowed a reconstruction of the infection process as follows: Hyphae first grew intercellularly between cortical cells (Fig 3A), and later gave rise to intracellular hyphae (Fig 3B). Intracellular hyphae were sparsely constricted at the penetration point (Fig 3B) and differed morphologically from the intercellular hyphae. They were generally coiled and terminated in the host cells with the formation of teliospores (Figs 3C and 4A and 4B and 5A–5G). Intercellular as well as intracellular hyphae were regularly septate and possessed dolipores without bands or caps (Figs 3C and 3D and 5A–5D). Clamp connections were absent. Intercellular as well as intracellular hyphae had electron-opaque, fibrillate walls. Septa showed a tripartite profile (Fig 3D).

Fig 3. Soral hyphae of Entorrhiza casparyana in root galls of Juncus articulatus, as seen by TEM.

(a) Section through an intercellular hypha surrounded by plant cells. (b) Section through an intercellular hypha extended into a cortical cell. Note that the intracellular part of the hypha is surrounded by the host plasma membrane. (c) Section through two hyphal coils in neighbouring cortical cells of J. articulatus. One host nucleus is visible at N, and a hyphal septum is visible at the arrow. (d) Section through a hyphal septum showing a dolipore without membranous caps (arrow). Note the basidiomycetous tripartite profile of the septum wall. Scale bar is 1 μm in (a-b), 2 μm in (c), and 0.1 μm in (d).

Fig 4. Sections through galls of Entorrhiza casparyana on Juncus articulatus, as seen by SEM.

(a) Section showing intracellular teliospore packets (one is indicated by an arrow). (b) Teliospore packet in detail, showing teliospores and hyphal spirals (one is indicated by an arrow). Scale bar is 1 mm in (a) and 20 μm in (b).

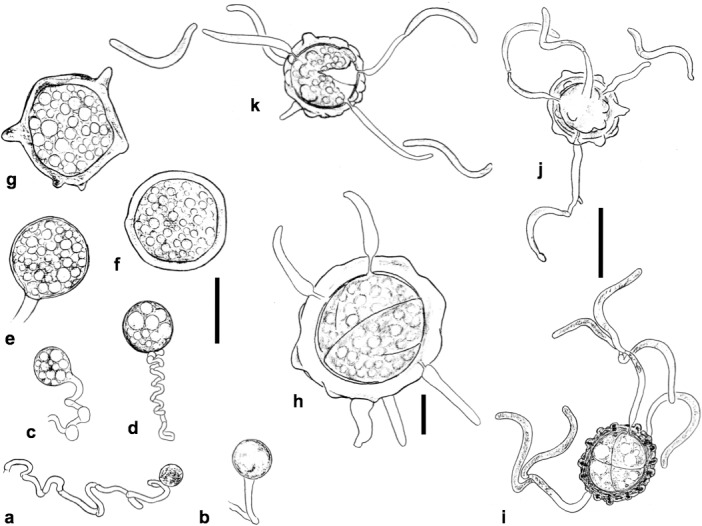

Fig 5. Line drawings of Entorrhiza casparyana.

(a-g) Intracellular more or less coiled hyphae and teliospores in different developing stages (host cells not drawn). (h-k) Germinating teliospores in different developing stages. Note the sigmoid shape of the propagules. Scale bar is 20 μm in (a-g, j-k) and 10 μm in (h).

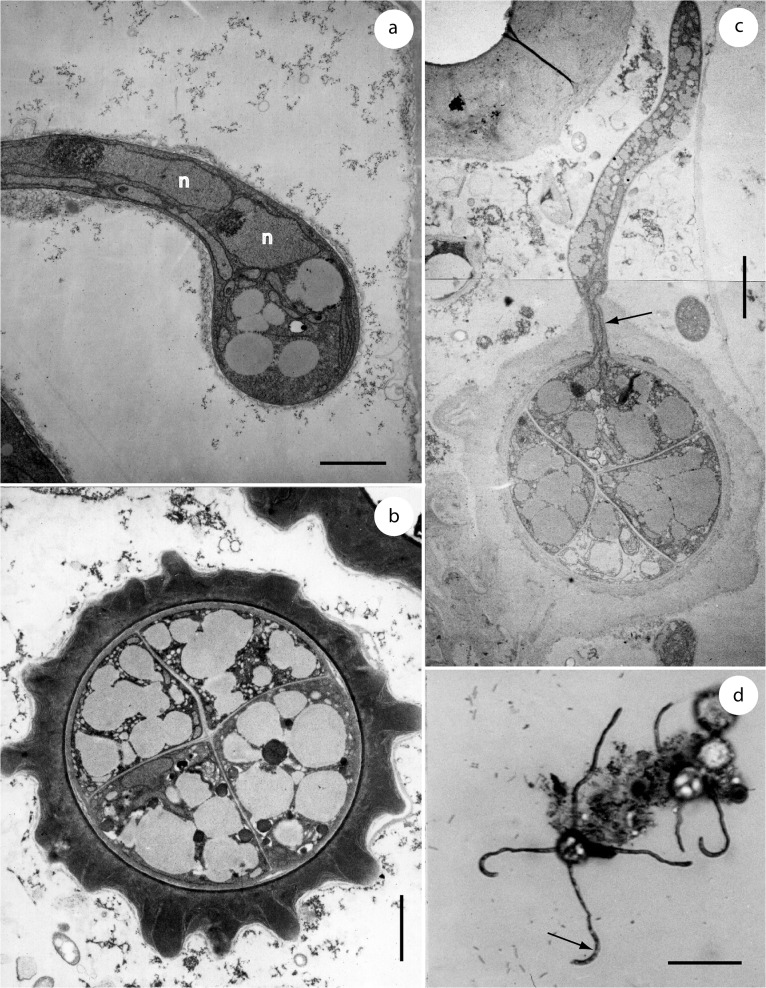

Because of the coiled nature of the intracellular hyphae they were difficult to trace in the TEM analyses. By examining serial sections we mostly detected two nuclei per hyphal cell (Fig 6A), but occasionally up to four nuclei could be observed in one cell. In young teliospores we mostly observed two nuclei. In Giemsa-stained material we usually observed one large nucleus in older teliospores that were stored in water at 7°C for two months.

Fig 6. Teliospore formation and germination of Entorrhiza casparyana, as seen by TEM (a-c) or LM (d).

(a) Section through an intracellular hyphal coil showing a terminal teliospore initial with two nuclei (n). (b) Section through a teliospore tetrad showing the cruciform septation. (c) Section through a teliospore tetrad showing the germination of one of the four teliospore compartments. One nucleus is visible at the arrow, probably migrating into the germination hypha. (d) Light microscopic micrograph of a germinating teliospore illustrated to show the synchronous development of the germination hyphae and the terminal sigmoid propagules (one is indicated by an arrow). Scale bar is 2 μm in (a-b), 3 μm in (c), and 40 μm in (d).

Germination in Entorrhiza casparyana started after teliospores had been stored in water at 7°C for 76 days. First, they became regularly two-celled by septation. Subsequently, the two segments in each primary teliospore divided synchronously so that regularly cruciform teliospore tetrads could be observed (Figs 5H–5K and 6B and 6C). The internal septa also had dolipores. In serial sections, we detected only one nucleus per teliospore compartment (Fig 6C). Germination hyphae arose synchronously from each compartment (Fig 6C and 6D). Finally, sigmoid monokaryotic propagules developed on each germination hypha (Figs 5H–5K and 6D). In our germination experiments on agar media these propagules did not germinate.

The interphasic mitotic spindle pole body (SPB) in E. casparyana is a single extranuclear hemispherical body that in transition from telophase to interphase contained a convex and completely internalized electron-opaque layer. SPB replication began with the appearance of an electron-dense bar on the nuclear periphery of the original SPB next to the nucleus (Fig 7A). Next, the original SPB disappeared and the bar transformed into a double-structured SPB. SPB material formed at each end of the bar and developed into the two SPB elements of the double-structured SPB (Fig 7B). Then the SPB elements increased in size and the layering became evident, whereas the middle piece decreased in size and finally disappeared, so that in late interphase / early prophase the two SPB elements appeared separated from each other (Fig 7C and 7D).

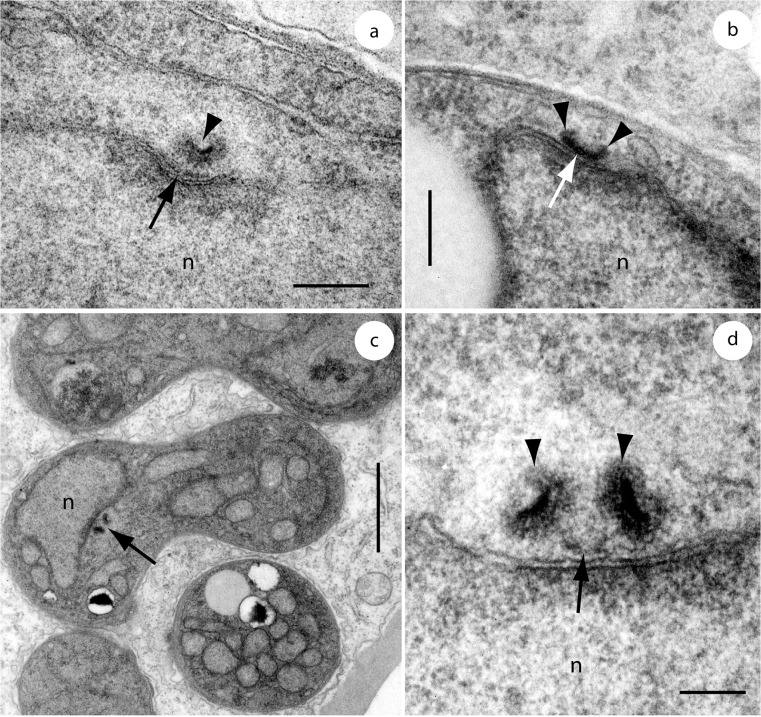

Fig 7. Spindle pole bodies (SPBs) of Entorrhiza casparyana, as seen by TEM.

(a) Median section through a postmitotic / early interphasic SPB showing the original hemispherical SPB with an internal electron-opaque layer (arrowhead) and an additional bar (arrowhead) next to the nuclear envelope. (b) Longitudinal section through a mid-interphasic SPB. The double structure of the SPB has begun to reconstitute by growth of SPB elements (arrowheads) at the ends of the electron-opaque bar (arrow). (c) Section through an intracellular hyphal coil showing one nucleus with a longitudinally sectioned premitotic SPB (arrow). (d) Detail of (c) illustrated to show the two enlarged SPB elements (arrowheads) connected by an elongated middle piece (arrow). Note the internal layering of the SPB elements. n, nucleus. Scale bar is 0.2 μm in (a-b), 1 μm in (c), and 0.1 μm in (d).

Taxonomy

Our study indicates that the Entorrhiza lineage does not belong to any of the described phyla of the Fungi (for the taxa see [14], [32–33]). Accordingly, we propose the following new phylum:

Entorrhizomycota R. Bauer, Garnica, Oberw., K. Riess, M. Weiß & Begerow, phylum nov. (Figs 1–7)

[MycoBank no: MB808783]

Members of the Fungi sensu Hibbett et al. [14] infecting roots with regularly septate coiled hyphae. Septal pores without Woronin bodies or membrane caps.

Remarks: Only the genus Entorrhiza C.A. Weber [1: p. 378] is included. Entorrhizomycetes was proposed by Begerow et al. [12: p. 908]; Entorrhizomycetidae, Entorrhizales, and Entorrhizaceae were established by Bauer & Oberwinkler in Bauer et al. [7: p. 1311].

Discussion

Phylogenetic placement of Entorrhiza

So far, only seven rDNA sequences have been published for four of 14 known species of Entorrhiza. In the analyses of Begerow et al. [12], [15] the taxon sampling was restricted to the subphylum Basidiomycota. However, these authors already noted that in analyses with several ascomycetes and zygomycetes “Entorrhiza was not always included in the Ustilaginomycetes” [15]. Matheny et al. [13] suggested that Entorrhiza is not nested within any described subphylum and might also represent the sister group of the rest of the Basidiomycota (see also [14]).

In general, these studies indicated that phylogenetic analyses based on rDNA sequences alone apparently do not allow the derivation of a statistically robust phylogenetic hypothesis for Entorrhiza. Therefore, we additionally sequenced the nuclear protein-coding genes rpb1 and rpb2 for three Entorrhiza species associated with different host plant families, E. aschersoniana, E. casparyana, and E. parvula. Because the spores of Entorrhiza develop intracellularly and are therefore not separable from the host tissue, and because the propagules of E. casparyana did not germinate in our germination experiments and we therefore did not obtain a culture, it has been impossible to sequence more genes to date.

Our combined 5-gene sequence analysis (Fig 2) is consistent with previous multi-gene studies [16–17]. In particular, Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, Glomeromycota, Kickxellomycotina, and Blastocladiomycota appear with high support, whereas Chytridiomycota was only moderately supported. Microsporidia as sister taxon to Fungi and a sister-group relationship of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are also in agreement with the results of previous studies in most aspects [16–17]. In addition, and in contrast with the results of Matheny et al. [13], our analysis yields a supported hypothesis for the phylogenetic position of Entorrhiza, suggesting that the Entorrhiza lineage is a monophyletic sister taxon to the rest of the Dikarya. However, branch support for the non-Entorrhiza Dikarya was only moderate in our five-gene ML (79%) and MP (72%) analyses (Fig 2). Only in Bayesian MCMC analysis did this group receive a branch support of 100% estimated posterior probability. We also found that the monophyletic non-Entorrhiza Dikarya received a low internode certainty value (ICA) of only 0.197 in the ML bootstrap analysis (Fig 2), indicating that at least one conflicting grouping is present in a considerable number of bootstrap replicates [29].

Thus, we also tested the alternative hypothesis that Entorrhiza is included in the Basidiomycota. Under this constraint, Entorrhiza appeared as the most basal lineage in the Basidiomycota in ML analysis (not shown), which taxonomically would be consistent with a new phylum Entorrhizomycota as well. In an SH test this constraint tree was not significantly worse than the overall ML tree shown in Fig 2.

On the whole, our five-gene analyses suggest that Entorrhiza is the sister group of all other Dikarya, though we cannot significantly reject an alternative topology in which Entorrhiza is sister to Basidiomycota. Both alternatives are consistent with our proposal of a new phylum Entorrhizomycota. Additional evidence for the first scenario comes from a closer inspection of the single-gene analyses. We found the highest average internode support (TCA value) in the ML tree inferred from the rpb2 alignment, indicating that bootstrap consistency in this analysis is higher than those in the ML analyses of the other genes analyzed here [34]. According to the rpb2 ML tree Entorrhiza is sister to the rest of the Dikarya. Future phylogenomic analyses hopefully provide a final confirmation or falsification of this hypothesis, once genomes of Entorrhiza have become available.

Subcellular and cellular characters

Morphologically, Entorrhiza shares more traits with Basidiomycota than with Ascomycota. As in basidiomycetes, but in contrast to ascomycetes, the vegetative hyphal cells are dikaryotic, the hyphal walls have an electron-opaque fibrillate substructure and the septa show a tripartite profile in E. casparyana [35–36]. In addition, SPB form, structure, and behavior in Entorrhiza casparyana are basidiomycetous (see [37] and the references therein). In the transition from telophase to interphase, the SPB is a single extranuclear hemispherical body that contains a completely internalised electron-opaque layer that is convex relative to the nuclear surface. SPB replication in Entorrhiza occurs as it does in basidiomycetes in general. An electron-dense bar first appears on the nuclear periphery of the original SPB next to the nucleus. After that the original SPB disappears and the bar transforms into a double-structured SPB. SPB material forms at each end of the bar, which develops into the two SPB elements of the double-structured SPB. Subsequently, the SPB elements increase in size and the layering becomes evident (Fig 7), whereas the middle piece decreases in size and finally disappears so that in late interphase / early prophase the two SPB elements are separated from each other. In contrast with Entorrhiza casparyana and basidiomycetes, the SPBs of ascomycetes are discoidal in form and duplicate by fission [38].

Teliospores of Entorrhiza germinate internally by becoming four-celled with cruciform septation [1], [8–9]. Although the meiotic stages have not been studied in detail, the changes in numbers of nuclei from binucleate to mononucleate to four-nucleate [8–9], the synchronous second division of the two teliospore segments, and the synchronous germination of the resulting teliospore tetrad indicate that they represent meiosporangia. Interestingly, based on experimental studies on Gymnosporangium, Helicogloea and Platygloea, Bauer and Oberwinkler [39] demonstrated that the basidial cells in phragmobasidia essentially represent meiospores and that the meiosporangial dispersal propagules accordingly represent secondary vegetative cells, comparable to the yeasts of Ustilago, or ballistosporic conidia of the rusts [40] (see also [41]). As particularly indicated by the formation of septal pores, the septation of the Entorrhiza teliospores is a hyphal septation, which is essentially identical to that of external transversely-septate phragmobasidia (see [42], and the references therein). On the other hand, the meiosporangial tetrads in Entorrhiza are also essentially identical to those of Tetragoniomyces uliginosus, a tremelloid mycoparasite [43]. Interestingly, T. uliginosus occurs on decaying plant material in wet habitats. As already noted by Oberwinkler and Bandoni [43] for T. uliginosus, the meiosporangial tetrads of Entorrhiza may also be an adaption for water dispersal in the soil. In addition, the basidiospores in Entorrhiza resemble the conidia of aquatic hyphomycetes [44]. Thus, a plausible scenario for the evolution of the aerial dispersal of meiospores in the Dikarya may, as a first step, have involved the formation of external elongate transversely-septate phragmobasidia in combination with the ballistosporic mechanism, with subsequent repeated evolution of holobasidia that apically give rise to ballistospores, allowing a denser packing of the basidia in hymenia and a more effective aerial spore release.

The meiosporangial tetrads in Entorrhiza also resemble the meiospore tetrads in asci of early diverged lineages of ascomycetes, e.g., in Saccharomyces and Schizosaccharomyces [45–46]. At first glance, the septation within phragmobasida and the formation of ascospores look quite different in comparison, but the underlying processes may be homologous [8], [45–46]. To build cell walls, in both processes vesicles accumulate adjacent to an initial membranous body and then fuse with the body and extrude their contents so that the initial body becomes enlarged. The main difference in the two processes is the initial body: in hyphal septation it is the plasma membrane sac, whereas in the development of the ascospore wall it is an ER cisterna that is associated with the cytoplasmic face of the SPB. However, three-dimensional imaging has shown that the plasma membrane sac and the ER cisternae are continuous anyway [46].

As for the evolutionary trend to aerial dispersal outlined above for basidiomycetes, from internal meiosporangia via phragmobasidia to holobasidia, we may also postulate an evolutionary trend to aerial dispersal in ascomycetes, via the formation of eutunicate asci.

In summary, meiosporangial tetrads, as in Entorrhiza, may represent the dikaryan meiosporangial prototype.

Coevolution of Entorrhiza with land plants

The species of Entorrhiza infest members of Cyperaceae and Juncaceae worldwide [2], [5]. The origin of the Dikarya (and thus also of the Entorrhiza lineage as its assumed sister group) was roughly dated at around 600 million years BP, more or less parallel to the first appearance of primitive land plants [47–48], whereas the origins of the known extant host groups of the Entorrhiza clade, the core Poales, has been dated at around 100 million years BP [49–50]. Because of this discrepancy, we hypothesise that the known species of the Entorrhiza clade and their respective host spectra reflect only the tip of the iceberg of a much broader group, comprising perhaps also the lower land plants. Because of the lack of any aboveground signal of infection, the host plants are difficult to detect in nature. There also might be members of the Entorrhiza clade that do not cause galls on the roots. To test this hypothesis, we are currently developing specific primers for an efficient molecular detection of this fascinating group of root-colonizing fungi.

Conclusions

For the phylogenetic placement of Entorrhiza two alternative hypotheses are most plausible: (i) Entorrhiza is the sister group to the rest of the Dikarya, or (ii) Entorrhiza is the sister group to Basidiomycota. The first topology was inferred in our phylogenetic analyses of a five-gene dataset. It is consistent with the interpretation of the Entorrhiza meiosporangium as representing the ancestral meiosporangium of Asco- and Basidiomycota. The second scenario, which is in agreement with ultrastructural similarities, could not significantly be rejected in ML analysis of our five-gene dataset. Based on its peculiar combination of morphological features we therefore propose, a new phylum of root-colonizing fungi, the Entorrhizomycota, which is compatible with both alternative phylogenetic positions discussed in this work.

Acknowledgments

This work was initiated by Robert Bauer who unexpectedly passed away before the manuscript was finished. We thank Ronny Kellner, Martin Kemler, Larissa Meteling, Sabine Silberhorn and Magdalena Wagner-Eha for technical assistance, and Matthias Lutz, Marcin Piątek and Meike Piepenbring for kindly providing specimens of Entorrhiza. Editor and anonymous reviewers contributed important suggestions and guidance. We are grateful for valuable comments on the manuscript by Marcin Piątek.

Data Availability

Sequences are available on GenBank and the alignment has been deposited at TreeBASE under submission ID S15778.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation, DFG (BA 75/3-1) and the Open Access Publishing Fund of Tuebingen University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Weber C (1884) Über den Pilz der Wurzelanschwellungen von Juncus bufonius . Botanische Zeitung 42: 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vánky K (2012) Smut Fungi of the World. St. Paul: APS. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fineran JM (1980) The structure of galls induced by Entorrhiza C. Weber (Ustilaginales) on roots of the Cyperaceae and Juncaceae. Nova Hedwigia 32: 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deml G, Oberwinkler F (1981) Investigations on Entorrhiza casparyana by light and electron microscopy. Mycologia 73: 392–398. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fineran JM (1978) A taxonomic revision of the genus Entorrhiza C. Weber (Ustilaginales). Nova Hedwigia 30: 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Piepenbring M, Bauer R, Oberwinkler F (1998) Teliospores of smut fungi. Teliospore walls and the development of ornamentation studied by electron microscopy. Protoplasma 204: 155–169. 10.1007/BF01280323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bauer R, Oberwinkler F, Vánky K (1997) Ultrastructural markers and systematics in smut fungi and allied taxa. Can. J. Bot. 75: 1273–1314. 10.1139/b97-842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bauer R, Begerow D, Oberwinkler F, Piepenbring M, Berbee ML (2001) Ustilaginomycetes In: McLaughlin DJ, McLaughlin EG, Lemke PA, editors. The Mycota, volume 7: Systematics and Evolution Berlin/Heidelberg/New York: Springer; pp. 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fineran JM (1982) Teliospore germination in Entorrhiza casparyana (Ustilaginales). Can. J. Bot. 60: 2903–2913. 10.1139/b82-351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oberwinkler F (2012) Evolutionary trends in Basidiomycota. Stapfia 96: 45–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oberwinkler (2012) Mykologie am Lehrstuhl Spezielle Botanik und Mykologie der Universität Tübingen, 1974–2011. Andrias 19: 23–110. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Begerow D, Stoll M, Bauer R (2006) A phylogenetic hypothesis of Ustilaginomycotina based on multiple gene analyses and morphological data. Mycologia 98: 906–916. 10.3852/mycologia.98.6.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matheny PB, Gossmann JA, Zalar P, Kumar TKA, Hibbett DS. 2006. Resolving the phylogenetic position of the Wallemiomycetes: an enigmatic major lineage of Basidiomycota. Can. J. Bot. 84: 1794–1805. 10.1139/b06-128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hibbett DS, Binder M, Bischoff JF, Blackwell M, Cannon PF, Eriksson OE, et al. (2007) A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycol. Res. 111: 509–547. 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Begerow D, Bauer R, Oberwinkler F (1997) Phylogenetic studies on the nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA of smut fungi and related taxa. Can. J. Bot. 75: 2045–2056. 10.1139/b97-916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. James TY, Kauff F, Schoch CL, Matheny PB, Hofstetter V, Cox CJ, et al. (2006) Reconstructing the early evolution of Fungi using a six-gene phylogeny. Nature 443: 818–822. 10.1038/nature05110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu YJ, Hudson MC, Hall BD (2006) Loss of the flagellum happened only once in the fungal lineage: phylogenetic structure of kingdom Fungi inferred from RNA polymerase II subunit genes. BMC Evol. Biol. 6: 74 10.1186/1471-2148-6-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matheny PB, Liu YJ, Ammirati JF, Hall BD (2002) Using RPB1 sequences to improve phylogenetic inference among mushrooms (Inocybe, Agaricales). Am. J. Bot. 89: 688–698. 10.3732/ajb.89.4.688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu YL, Whelen S, Hall BD (1999) Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 16: 1799–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morgenstern B (2004) DIALIGN: multiple DNA and protein sequence alignment at BiBiServ. Nucl. Acids Res. 32: W33–W36. 10.1093/nar/gkh373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Begerow D, John B, Oberwinkler F (2004) Evolutionary relationships among β-tubulin gene sequences of basidiomycetous fungi. Mycol. Res. 108: 1257–1263. 10.1017/S0953756204001066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katoh K, Standley DM (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Castresana J (2000) Selection of conserved blocks from mutliple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17:540–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stamatakis A (2006) RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Felsenstein J (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Le SQ, Dang CC, Gascuel O (2012) Modeling protein evolution with several amino acid replacement matrices depending on site rates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29: 2921–2936. 10.1093/molbev/mss112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Swofford DL (2002) PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*And Other Methods), v. 4.0b10. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M (1999) Multiple comparisons of log-likelihoods with applications to phylogenetic inference. Mol. Biol. Evol. 13: 964–969. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salichos L, Stamatakis A, Rokas A (2014) Novel information theory-based measures for quantifying incongruence among phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31: 1261–1271. 10.1093/molbev/msu061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gersterberger P, Leins P (1978) Rasterelektronenmikroskopische Untersuchungen an Blütenknospen von Physalis philadelphica (Solanaceae)–Anwendung einer neuen Präparationsmethode. Ber. Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 91: 381–387. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.1978.tb03660.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Humber RA (2012) Entomophthoromycota: A new phylum and reclassification for entomophthoroid fungi. Mycotaxon 120: 477–492. 10.5248/120.477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones MDM, Forn I, Gadelha C, Egan MJ, Bass D, Massana R, et al. (2011) Discovery of novel intermediate forms redefines the fungal tree of life. Nature 474: 200–203. 10.1038/nature09984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salichos L, Rokas A (2013) Inferring ancient divergences requires genes with strong phylogenetic signals. Nature 497: 327–331. 10.1038/nature12130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kreger-van Rij NJW, Veenhuis M (1971) A comparative study of the cell wall structure of basidiomycetous and related yeasts. J. General Microbiol. 68: 87–95. 10.1099/00221287-68-1-87 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nagler A, Bauer R, Berbee ML, Vánky K, Oberwinkler F (1989) Light and electron microscopic studies of Schroeteria delastrina and S. poeltii . Mycologia 81: 884–895. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bauer R, Berbee ML, Oberwinkler F (1991) An electron microscopic study of meiosis and the spindle pole cycle in the smut fungus Sphacelotheca polygoni-serrulati . Can. J. Bot. 69: 245–255. 10.1139/b91-035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heath IB (1981) Nucleus associated organelles of fungi. Int. Rev. Cytol. 69: 191–221. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bauer R, Oberwinkler (1986) Experimentell-ontogenetische Untersuchen an Phragmobasidien. Z. Mykol. 52: 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bauer R, Oberwinkler F (1988) Nuclear degeneration during ballistospore formation of Cronartium asclepiadeum (Uredinales). Bot. Acta 101: 272–282. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bandoni RJ (1984) The Tremellales and Auriculariales: an alternative classification. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Jpn. 25: 489–530. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bauer R, Oberwinkler F (1994) Meiosis, septal pore architecture and systematic position of the heterobasidiomycetous fern parasite Herpobasidium filicinum . Can. J. Bot. 72: 1229–1242. 10.1139/b94-151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oberwinkler F, Bandoni RJ (1981) Tetragoniomyces gen. nov. and Tetragoniomyceteae fam. nov. (Tremellales). Can. J. Bot. 59: 1034–1040. 10.1139/b81-141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ingold CT (1979) Advances in the study of so-called aquatic hyphomycetes. Amer. J. Bot. 66: 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Neiman AM (2005) Ascospore formation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69: 565–584. 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.565-584.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Neiman AM (2011) Sporulation in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cervisiae . Genetics 189: 737–765. 10.1534/genetics.111.127126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lücking R, Huhndorf S, Pfister DH, Plata ER, Lumbsch HT (2009) Fungi evolved right on track. Mycologia 101: 810–822. 10.3852/09-016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Floudas D, Binder M, Riley R, Barry K, Blanchette RA, Henrissat B, et al. (2012) The paleozoic origin of enzymatic lignin decomposition reconstructed from 31 fungal genomes. Science 336: 1715–1719. 10.1126/science.1221748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wikström N, Savolainen V, Chase MW (2001) Evolution of the angiosperms: calibrating the family tree. Proc. R. Soc. B 268: 2211–2220. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Janssen T, Bremer K (2004) The age of major monocot groups inferred from 800+ rbcL sequences. Bot. J. Linnean Soc. 146: 385–398. 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2004.00345.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences are available on GenBank and the alignment has been deposited at TreeBASE under submission ID S15778.