Abstract

Lumbar stenosis is an increasingly common pathological condition that is becoming more frequent with increasing mean life expectancy, with high costs for society. It has many causes, among which degenerative, neoplastic and traumatic causes stand out. Most of the patients respond well to conservative therapy. Surgical treatment is reserved for patients who present symptoms after implementation of conservative measures. Here, a case of severe stenosis of the lumbar spine at several levels, in a female patient with pathological and surgical antecedents in the lumbar spine, is presented. The patient underwent two different decompression techniques within the same operation.

Keywords: Spine, Spinal stenosis, Laminectomy

Resumo

A estenose lombar é uma patologia cada vez mais frequente, que acompanha o aumento da esperança média de vida e que comporta custos elevados para a nossa sociedade. Apresenta inúmeras causas, entre as quais destacam-se a degenerativa, a neoplásica e a traumática. A maioria dos pacientes responde bem à terapêutica conservadora. O tratamento cirúrgico está reservado para aqueles doentes que apresentem sintomatologia após a implementação de medidas conservadoras. É apresentado um caso de estenose grave da coluna lombar em vários níveis, numa doente do sexo feminino com antecedentes patológicos/cirúrgicos da coluna lombar, na qual foram aplicadas duas técnicas distintas de descompressão, no mesmo ato cirúrgico.

Palavras-chave: Coluna vertebral, Estenose espinal, Laminectomia

Introduction

Lumbar stenosis is defined as a pathological narrowing of the vertebral canal and/or intervertebral foramens that leads to compression of the thecal sac and/or the nerve roots. It may be confined just to one segment (two adjacent vertebrae and the intervertebral disc, joint facets and corresponding ligaments) or, in situations of greater severity, it may encompass two or more segments1 and present several etiologies.

As mean life expectancy increases, people of greater age are presenting active lifestyles. Consequently, functional limitation and pain caused by symptomatic degenerative pathological conditions of the spine have become more frequent and lumbar stenosis has become an important disease.

The main clinical manifestations are lumbalgia, generally associated with irradiation to the lower limbs, and neurogenic claudication.

Radiological examinations, especially lumbar X-rays, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are useful and essential tools for diagnosing and characterizing lumbar stenosis.

Therapy for this condition continues to be a clinical challenge, with various options available.

Case report

The patient was a 53-year-old white female who was observed in an orthopedic outpatient consultation with a complaint of lumbalgia in the L5–S1 region in situations of constant loading, with irradiation to both legs. The condition had been evolving for around two years, despite conservative therapy consisting of analgesia, NSAIDs, muscle relaxants and physiotherapy, which had been instituted by the family doctor. The patient reported having neurogenic claudication. She did not have any previous history of trauma.

She reported having personal antecedents of a disc hernia, which was present in two segments of the lumbar spine (L3–L4 and L4–L5), and having undergoing classical lumbar discectomy.

On physical examination, she presented pain on palpation of the lumbar spine apophyses and paravertebral masses. She was bilaterally positive for Lasègue's sign. A neurological examination revealed a foot inclined to the right.

Lumbar MRI showed a bulging intervertebral disc, hypertrophy of the joint facets and yellow ligaments at the levels L2–L3, L3–L4, L4–L5 and L5–S1, which caused narrowing of the spinal canal, with impairment of the roots of L4, L5 and S1 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Electromyography was also performed on the lower limbs, and this revealed severe radiculopathy at L5 and S1.

Fig. 1.

MRI of the lumbar spine (sagittal slice), in which lumbar stenosis can be seen at L2–S1.

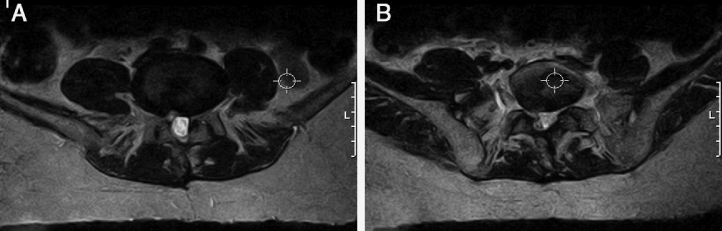

Fig. 2.

MRI of lumbar spine (axial slice), in which narrowing of the spinal canal can be seen at the levels (A) L4–L5 and (B) L5–S1.

From this, a diagnosis of lumber stenosis at L2–L3, L3–L4, L4–L5 and L5–S1 was established, associated with neurological deficits, and surgical treatment was proposed. The patient underwent lumbar recalibration of L2–L3 and L3–L4 by means of the Senegas technique at L4–L5 and L5–S1 with laminectomy and fixation using transpedicular screws and posterolateral arthrodesis, with an autologous bone graft (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

X-ray of the lumbar spine after surgery with arthrodesis at L4–S1.

The patient presented regression of the neurological deficits after the operation. Currently, she is being followed up as an outpatient and is asymptomatic.

Discussion

The incidence of lumbar stenosis in the general population is between 1.7% and 8%, and it increases from the fifth decade of life onwards.2

It can be classified according to either its etiology or its anatomy. The etiological classification is divided into congenital stenosis and acquired/degenerative stenosis. Congenital stenosis is characterized by narrowing of the vertebral canal that is either idiopathic or secondary to bone dysplasia such as achondroplasia. Acquired/degenerative stenosis may occur as a result of metabolic disease (such as Paget's disease), tumors, infections, osteoarthritic alterations or instability with or without spondylolisthesis. The anatomical classification is used to identify specific areas of stenosis and is used as a “guide” to surgical decompression. Four types of stenosis can be defined: (1) central; (2) lateral recess; (3) foraminal; and (4) extraforaminal.

Adult degenerative lumbar stenosis, which was present in this clinical case, is almost always associated with osteophytic/degenerative increases in the joint facets, and these alterations are caused by segmental instability. It is believed that this entire degenerative process starts with degeneration of the intervertebral disc, followed by collapse of the disc space.3 This gives rise to abnormal movement kinetics, with consequent osteoarthrosis/hypertrophy of the joint facets, which results in diminution of the central and intervertebral portion of the vertebral canal. Because of the loss of disc height and hypertrophy of the joint facets, shortening and thickening of the yellow ligament is seen, which also contributes toward diminishing the central space of the vertebral canal. In some patients, degenerative cysts can also be seen in the synovial region of the joint facets, which cause a “mass” effect and contribute toward a greater degree of lumbar stenosis.

The classical clinical presentation of lumbar stenosis consists of bilateral neurogenic claudication, along with chronic lumbalgia with irradiation to the lower limbs, which worsens with standing up for prolonged periods, physical activity and lumber extension. Some patients describe improvement of the symptoms when they sit down and/or flex the lumbar spine. Neurogenic claudication needs to be distinguished from vascular claudication. The latter does not present worsening while the patient is standing up for a long time, and it is not alleviated through flexion of the lumbar spine, unlike what is seen with neurogenic claudication. Objective examination on patients with vascular claudication shows that they generally present abnormalities of the arterial pulse, along with trophic alterations (thinner and shinier skin). Effort tests may be useful in distinguishing between these two clinical entities. A small number of patients present priapism and/or sphincter dysfunction in association with neurogenic claudication, which reveals a more severe degree of lumbar stenosis. Alterations to the sensitivity of the lower limbs and tendon reflexes may also be present.

There are several pathological conditions that present similar symptoms, and it is necessary to make a differential diagnosis. It is important to rule out tumors (both primary tumors and metastases), Paget's disease, infections, trochanteric bursitis and coxarthrosis/gonarthrosis.4

The diagnosis of lumbar stenosis can be confirmed through using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT is the examination that presents better cost-efficacy, and it provides an excellent level of detailing of the bone structures, especially in the region of the lateral recess. MRI provides a better view of the soft tissues, which is very useful in evaluating the pathology of the intervertebral disc, and its efficacy is better than that of CT and myelography.5 Electromyography, which tests the velocity of nerve conduction and assesses the evoked somatosensory potentials, does not form part of the routine evaluation of lumbar stenosis. It is useful for distinguishing radiculopathy because of the lumbar compression and diabetic neuropathy that affect the peripheral sensory-motor nerves.

There are two main variants of treatments for lumbar stenosis: conservative and surgical.

The pillars of conservative consist of use of drugs, physiotherapy, corsetry and epidural injections of corticosteroids. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs provides an improvement in the symptoms, though diminishing the inflammatory response associated with compression of neural elements. Physiotherapy is based on stretching and strengthening exercises for the lumbar spine, along with aerobic exercises (static bicycle). Corsetry may be useful for alleviating the symptoms, through diminishing lumbar lordosis, and it presents better results in patients with spondylolisthesis.6 Injection of corticosteroids for treating lumbar pathological conditions, notably lumbar stenosis, remains a controversial procedure.7 To date, several studies have been unable to demonstrate any effective response from injections for resolving radiculopathy.7

Surgical treatment should be used after conservative therapies have been implemented, given that lumbar stenosis is not a life-threatening entity, although progression of neurological deficits and cauda equina syndrome are indications for urgent surgical decompression. Standard decompressive laminectomy involves removal of the spinous apophyses, lamina and yellow ligament from the affected levels. This approach enables direct viewing of the nerve roots and their decompression along the entire path. Less invasive decompressive surgical techniques that preserve posterior bone and ligament structures have recently been developed in an attempt to diminish the postoperative instability. These techniques include laminectomy with angular resection of the anterior and lateral portions of the lamina, selective unilateral/bilateral laminectomy, partial laminectomy and lumbar laminoplasty.8, 9, 10 In certain cases, it is possible to apply several surgical techniques at different vertebral levels in the same patient and to reserve standard laminectomy for the levels that present stenosis of greater severity.5 The clinical results from surgical decompression of lumber stenosis have been favorable,11 with remission of the symptoms, although recent studies have indicated that the initial clinical improvement tends to deteriorate with the passage of time.12 Spondylolisthesis following decompression without lumbar arthrodesis is one of the commonest complications. Therefore, arthrodesis of the lumbar spine with autologous grafts and fixation with transpedicular screws should be performed on all patients who present instability due to resection of the joint facets during decompression.13 It is essential to perform lumbar arthrodesis on patients with lumbar stenosis and spondylolisthesis or degenerative scoliosis.13

Through presenting this case, the aim is to highlight the fact that this was a patient with pathological/surgical antecedents in the lumbar spine, who presented severe stenosis with involvement of the lumbar spine at different levels, and to whom two distinct decompression techniques were applied in the same surgical procedure, with good results.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: Sá P, Marques P, Alpoim B, Rodrigues E, Félix A, Silva L, et al. Estenose lombar: caso clínico. Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49:405–408.

Work performed in the Alto Minho Local Healthcare Unit, Viana do Castelo, Portugal.

References

- 1.Spivak J.M. Current concepts review. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(7):1053–1066. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199807000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman J.R., Pensak M.J. Prevention of venous thromboembolic disease after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):1801–1811. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkaldy-Willis W.H., Wedge J.H., Yong-Hing K., Reilly J. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine (Phila PA 1976) 1978;3(4):319–328. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jönsson B., Strömqvist B. Symptoms and signs in degeneration of the lumbar spine. A prospective, consecutive study of 300 operated patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(3):381–385. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B3.8496204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Postacchini F., Amatruda A., Morace G.B., Perugia D. Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of lumbar spinal canal stenosis. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1991;17(3):327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willner S. Effect of a rigid brace on back pain. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56(1):40–42. doi: 10.3109/17453678508992977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rydevik B.L., Cohen D.B., Kostuik J.P. Spine epidural steroids for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila PA 1976) 1997;22(19):2313–2317. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanamori M., Matsui H., Hirano N., Kawaguchi Y., Kitamoto R., Tsuji H. Trumpet laminectomy for lumbar degenerative spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6(3):232–237. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199306030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aryanpur J., Ducker T. Multilevel lumbar laminotomies: an alternative to laminectomy in the treatment of lumbar stenosis. Neurosurgery. 1990;26(3):429–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuji H., Itoh T., Sekido H., Yamada H., Katoh Y., Makiyama N. Expansive laminoplasty for lumbar spinal stenosis. Int Orthop. 1990;14(3):309–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00178765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner J.A., Ersek M., Herron L., Deyo R. Surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. Attempted meta-analysis of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postacchini F., Cinotti G., Gumina S., Perugia D. Long-term results of surgery in lumbar stenosis. 8-year review of 64 patients. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1993;251:78–80. doi: 10.3109/17453679309160127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Booth R.E., Jr., Spivak J. The surgery of spinal stenosis. Instr Course Lect. 1994;43:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]