Abstract

The aim was to report on a rare case of osteochondroma of the left ischium, which evolved with compression of the sciatic nerve, thus causing sciatic pain in the homolateral lower limb. The patient was female and presented sciatic pain that was treated clinically for one year. However, the pain evolved with increasing intensity and worsened with hip movement. This was associated with diminished motor force and paresthesia of the homolateral lower limb. Radiological investigation of the region showed a bone lesion in the external portion of the left ischium, in the path of the sciatic nerve. Tomographic reconstruction showed cortical continuity with the bone of origin, i.e., a pattern characteristic of osteochondroma. En-bloc resection of the lesion was performed using the Kocher-Langerbeck route, and the anatomopathological analysis proved that it was an osteochondroma. The patient's neurological symptoms improved and, after two months of follow-up, she remained asymptomatic and without any signs of recurrence. Since osteochondroma is the commonest benign bone tumor, it should be taken into consideration in the diagnostic investigation of compressive tumor lesions that could affect the sciatic nerve.

Keywords: Oncology, Orthopedics, Sciatic nerve, Pelvis, Sciatica

Resumo

Relatar um caso raro de osteocondroma do ísqueo esquerdo, que evoluiu com compressão no nervo ciático e provocou ciatalgia no membro inferior homolateral. Paciente do sexo feminino apresentou ciatalgia e foi feito tratamento clínico por um ano. Porém a dor evoluiu, aumentou de intensidade e piorou com a movimentação do quadril, associada a diminuição da força motora e a parestesia do membro inferior homolateral. A investigação radiológica da região mostrou uma lesão óssea na porção externa do ísqueo esquerdo e no trajeto do nervo ciático. A reconstrução tomográfica evidenciou continuidade cortical com o osso de origem, padrão característico de osteocondroma. Fez-se a ressecção em bloco da lesão pela via de Kocher-Langerbeck e o estudo anatomopatológico provou ser um osteocondroma. Os sintomas neurológicos da paciente melhoraram e, após dois anos de acompanhamento, ela permanece assintomática e sem sinais de recorrência. Por ser o tumor ósseo benigno mais comum, o osteocondroma deve ser considerado na investigação diagnóstica de lesões tumorais compressivas, que podem acometer o nervo ciático.

Palavras-chave: Oncologia, Ortopedia, Nervo ciático, Pelve, Ciática

Introduction

Osteochondromas (exostoses or endochondromatous exostoses) are common bone tumors. They account for 8.5% of bone tumors and 36% of benign bone tumors.1 They can occur as solitary tumors or as multiple exostoses.

The predominant location for osteochondromas is the region proximal to the knee (distal femur and proximal tibia), followed by the humerus and proximal femur.2 Osteochondromas are generally diagnosed during childhood and adolescence. The clinical manifestations depend on occurrences of fractures at the base of the exostosis and inflammation and compression in the structures surrounding the tumor mass. Pelvic locations are uncommon and account for 5.6% of the cases, while cases affecting the ischium are even less common and account for only 0.4% of the cases.3 This location has complex anatomy, allows compression of the sciatic nerve and evolves with sciatic pain that is difficult to investigate clinically.

The objective of this study was to report on a case of ischial osteochondroma in which the unusual location allowed compression of the sciatic nerve and caused chronic sciatic pain.

Case report

The patient was a 42-year-old female patient who presented sciatic pain in her left leg, from the hip to the foot, with paresthesia on the anterolateral face of the left leg and foot, without alteration of the patellar reflex (L4) or Achilles reflex (S1). She had a negative Lasègue test. The patient underwent radiography and computed tomography (CT) of the lumbar spine and the results obtained were normal. She was started on clinical treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids, but without improvement. Over a one-year period, the pain progressed and started to worsen with movement of the left hip, along with diminished motor strength (grade 4) on dorsiflexion of the foot (L4), extension of the hallux (L5) and plantar flexion (S1). Imaging examinations of this region were then requested.

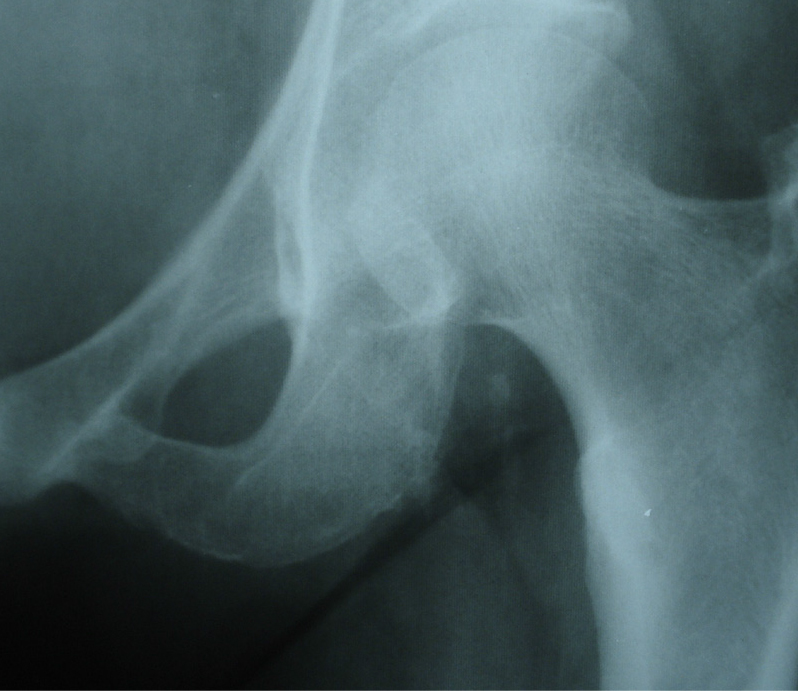

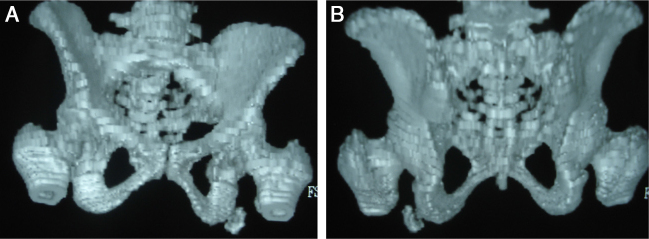

Radiography of the left hip (AP view) showed slight and poorly defined alteration of the external portion of the ischium (Fig. 1). CT of the pelvis was then requested, on which tumor development with bony characteristics was observed in the left ischium. It measured approximately 4 cm, was pedunculate and well-delimited, lay on the path of the sciatic nerve and was compatible with an osteochondroma (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative radiograph on the left hip, in AP view, showing slight bone alteration in the ischium.

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional tomographic reconstruction of the pelvis showing pedunculate tumor development in bone of the left ischium, along the path of the sciatic nerve, in front view (A) and rear view (B).

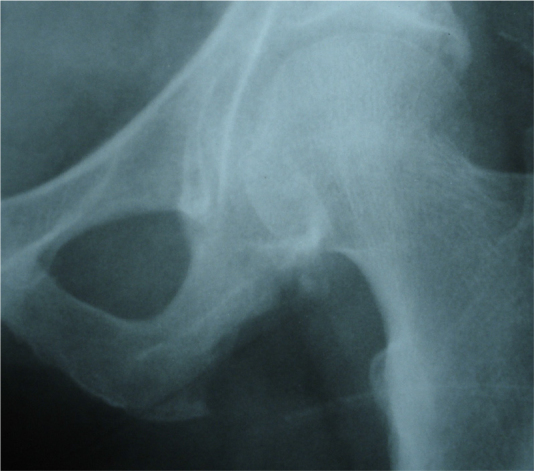

En-bloc resection surgery was performed on the tumor development in the left ischium, by means of the posterior Kocher-Langerbeck route, and the sciatic nerve was decompressed (Fig. 3). Anatomopathological examination of the surgical specimen confirmed the hypothesis of osteochondroma. After the surgery, the patient's neurological symptoms improved and she remains asymptomatic after two years of follow-up.

Fig. 3.

After the operation, with en-bloc resection of the tumor development.

Discussion

The initial approach in cases of lumbar sciatic pain is difficult because the differential diagnosis is extensive. There are different forms of vertebral involvement and clinical conditions without direct involvement that may mimic radiculalgia. The investigation therefore needs to integrate signs, symptoms, physical examinations, imaging examinations and laboratory tests, in order to guide logical management. The imaging investigation should be done carefully because the findings are often nonspecific and thus should be interpreted within a broader clinical context.

This patient arrived with complaints of sciatic pain and the radiological evaluation complemented with CT on the lumbar spine did not show alterations and ruled out the hypothesis of radicular compression. CT is the best method for viewing the bone architecture, but it is inferior to magnetic resonance imaging for evaluating soft tissues.4 At that time, the clinical diagnosis was defined as mechanical lumbar sciatic pain. Anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids were prescribed and the case was followed up for one year. Over this period, the pain worsened, which was a warning sign that raised the suspicion of systemic illness. Moreover, clinical examination showed grade 4 motor impairment of the nerve roots of L4 (dorsiflexion of the foot), L5 (extension of the hallux) and S1 (plantar flexion). The investigation was facilitated by the specific complaint of worsening of the pain with hip movement. AP radiographs of the region were requested and a lesion was found in the left ischium (Fig. 1). Tomographic reconstruction of the pelvis made it clear that this was a tumor development on the path of the left sciatic nerve that was compatible with osteochondroma, which explained the condition of progressive sciatic pain.

Osteochondromas are bone exostoses formed by cortical and medullary bone that is continuous with the originating bone and is covered with a coating of hyaline cartilage. Osteochondromas have their own growth plate, which produces bone that forms the exostosis. It is believed that osteochondromas arise from a change in growth direction of the epiphyseal disc, which grows persistently and later on undergoes endochondral calcification. The lesion continues to grow from the cartilaginous coating, just like a normal epiphyseal disc, and therefore growth after skeletal maturity is reached during puberty is not expected. This explains why the peak incidence of osteochondromas is in the second decade of life.4 The patient reported here was in her fifth decade of life (42 years of age), an age group in which only 5% of the diagnoses are made.5

Osteochondromas can affect any bone within endochondral ossification. The greatest incidence of osteochondromas occurs in the knee region (distal metaphysis of the femur and proximal metaphysis of the tibia), followed by the proximal regions of the humerus and femur. Occurrences in the ischium are uncommon and account for 0.4% of the cases.5 They can be solitary or multiple. The latter are associated with multiple hereditary exostosis, which is an autosomal dominant syndrome. Complications occur more frequently with this syndrome and include deformity (cosmetic or bone), fractures, vascular impairment, formation of pouches, malignant transformation and neurological sequelae. Despite this vast range of clinical manifestations, osteochondromas are generally asymptomatic and they are diagnosed by chance.

Osteochondromas are diagnosed radiologically. The lesions are characterized by continuation of the cortical and spongy bone with the underlying bone (Fig. 1). The hyaline cartilage is not seen on radiographic examination, unless it has become calcified, when it acquires an appearance of cotton wool-like stains, which suggests that osteochondromas have a benign nature and are long lasting. Thick cartilage that is invisible on radiographs is predictive of malignity.3 CT is essential for evaluating cases in complex anatomical sites (for example, in the pelvis, scapular belt, limb roots and spine).4 Tomographic reconstruction defined the present case and precisely showed a pedunculate lesion measuring 4 cm, located along the path of the left sciatic nerve (Fig. 2).

The presence of an osteochondroma is not an absolute indication for surgical resection. An expectant approach is taken in cases in which there are no clinical manifestations. Surgery is indicated in cases of pedunculate tumors (which are generally associated with complications) or when there is compression of nerves, arteries or tendons, or functional and anatomical alterations. Therefore, in the present case, the progressive neurological deficit in the leg comprised a formal indication for surgery. En-bloc resection was performed (Fig. 3). The Kocher-Langerbeck route was used and no intercurrences were observed either during the immediate postoperative period or later on. The importance of ample resection is that the presence of remainders of the perichondrium and the cartilaginous coating may enable local recurrence of the osteochondroma.

Malignant transformation is the complication that is most feared, but this has low frequency and occurs in 1% of solitary osteochondromas and 3–5% of multiple exostoses.6 The warning signs are rapid growth of the lesion, appearance of pain, thickening of the cartilage coating or discontinuity of the exostosis with the underlying cortical bone, when the demarcation of the lesion surface is radiologically lost. The transformation generally occurs to grade 1 chondrosarcoma. The anatomopathological examination on the surgical specimen confirmed the radiological suspicion of osteochondroma, and the two-year postoperative radiographic and clinical follow-up on the patient ruled out the possibility of malignant transformation or local recurrence of the lesion.

The neurological impairment that was presented regressed completely consequent to the surgical decompression and strength grade 5 was achieved for the myotomes corresponding to L4, L5 and S1. Complete remission of the compressive symptoms relating to osteochondromas in other topographical areas has generally been observed,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 for example Horner's syndrome in cases of cervical osteochondroma and radicular compression syndrome in cases of spinal osteochondroma. Because of the scarcity of cases, these is a lack of data for making specific prognostic evaluations on sciatic pain secondary to compression of the sciatic nerve due to ischial osteochondromas.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: de Moraes FB, Silva P, do Amaral RA, Ramos FF, Silva RO, de Freitas DA. Osteocondroma solitário de ísqueo: uma causa não usual de ciatalgia: relato de caso. Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49:313–316.

Work performed at the Orthopedics and Traumatology Clinic, Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil.

References

- 1.Defino H.L., Pereira C.U., Barbosa C.V.P. Revinter; Rio de Janeiro: 2002. Tumores benignos e lesões pseudotumorais da coluna vertebral. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radu A.S. Síndromes lombares. In: Lopes A.C., editor. Tratado de clínica médica. Roca; São Paulo: 2006. pp. 1732–1742. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia R.J. Elsevier; Rio de Janeiro: 2005. Diagnóstico e tratamento de tumores ósseos. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphey M.D., Choi J.J., Kransdorf M.J., Flemming D.J., Gannon F.H. Imaging of osteochondroma: variants and complications with radiologic–pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20(5):1407–1434. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.5.g00se171407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao C.Q., Jiang S.D., Jiang L.S., Dai L.Y. Horner syndrome due to a solitary osteochondroma of C7: a case report and review of the literature. Spine (Philadelphia, PA, 1976) 2007;32(16):E471–E474. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3180bc225d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han I.H., Kuh S.U. Cervical osteochondroma presenting as brown-sequard syndrome in a child with hereditary multiple exostosis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;45(5):309–311. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.45.5.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gürkanlar D., Aciduman A., Günaydin A., Koçak H., Celik N. Solitary intraspinal lumbar vertebral osteochondroma: a case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11(8):911–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byung-June J., Seung-Eun C., Sang-Ho L., Hyeop J.S., Suk P.S. Solitary lumbar osteochondroma causing sciatic pain. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74(4):400–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J., Xu C.R., Wu H., Pan H.L., Tian J. Osteochondroma in the lumbar intraspinal canal causing nerve root compression. Orthopedics. 2009;32(2):133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtori S., Yamagata M., Hanaoka E., Suzuki H., Takahashi K., Sameda H. Osteochondroma in the lumbar spinal canal causing sciatic pain: report of two cases. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(1):112–115. doi: 10.1007/s007760300019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bess R.S., Robbin M.R., Bohlman H.H., Thompson G.H. Spinal exostoses: analysis of twelve cases and review of the literature. Spine (Philadelphia, PA, 1976) 2005;30(7):774–780. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000157476.16579.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srikantha U., Bhagavatula I.D., Satyanarayana S., Somanna S., Chandramouli B.A. Spinal osteochondroma: spectrum of a rare disease. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8(6):561–566. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/8/6/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]