Abstract

Cognitive impairment (CI) remains common despite access to cART; it has been linked to HIV-specific, HIV-related and HIV-unrelated factors. Insulin resistance (IR) was associated with CI in the early cART era, when antiretroviral medications had greater mitochondrial and metabolic toxicity. We sought to examine these relationships in the current cART era of reduced antiretroviral toxicities. This study examined IR among non-diabetics in relation to a one-hour neuropsychological test battery among 994 women (659 HIV-infected and 335 HIV-uninfected controls) assessed between 2009 and 2011. The mean (Standard Deviation, SD) age of the sample was 45.1 (9.3) years. The HIV-infected sample had a median interquartile range (IQR) Cluster of Differentiation 4 (CD4) T-lymphocyte count of 502 (310-727) cells/μL and 54% had undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels. Among all, the Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA) of IR ranged from 0.25 to 37.14. In adjusted models, increasing HOMA was significantly associated with reduced performance on Letter Number Sequencing (LNS) attention task (β=-0.10, p<0.01) and on Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) recognition (β=-0.10, p<0.01) with weaker but statistically significant associations on phonemic fluency (β=-0.09, p=0.01). An HIV*HOMA interaction effect was identified on the LNS attention task and Stroop trials 1 and 2, with worse performance in HIV-infected vs. HIV-uninfected women. In separate analyses, cohort members who had diabetes mellitus (DM) performed worse on the grooved pegboard test of psychomotor speed and manual dexterity. These findings confirm associations between both IR and DM on some neuropsychological tests and identify an interaction between HIV status and IR.

Suggested key words: HIV, Insulin Resistance, Dementia, Cognition, cART

INTRODUCTION

Substantial gaps remain in our understanding of the causes of cognitive impairment (CI) among treated HIV-infected patients in the era of combination antiretroviral therapies (cART). The frequency of HIV-associated Neurocognitive Impairment (HAND) remains unexpectedly high among patients receiving cART (Tozzi et al. 2007). A study conducted with over 1500 community dwelling HIV-infected subjects attending academic centers found that about one-half performed below expectations on cognitive tests; although a substantial proportion of these individuals did not have suppression of virus in plasma (Heaton et al. 2010). HIV-specific factors remain important, given findings that the quantitative burden of HIV DNA in CD14+ cells and, separately, levels of plasma CD163, are associated with HAND among individuals with undetectable plasma HIV RNA (Burdo et al. 2013; Valcour et al. 2013). Increasingly, HIV-associated factors, such as medication toxicities, are under consideration, particularly in the setting of an aging population (Clifford and Ances 2013).

Despite availability of newer antiretroviral medications, metabolic dysfunction remains, perhaps owing to multiple factors including chronic inflammation and the long-term exposure to antiretroviral medications (Srinivasa and Grinspoon 2014). Previous analyses using data from the early cART era identified associations between metabolic derangements, principally insulin resistance (IR) and diabetes mellitus (DM), and cognition, but more recent work has brought this association into question (McCutchan et al. 2012; Valcour et al. 2012). Because the strongest evidence was based on cohorts enrolled during the early cART era, when antiretroviral medications were more closely linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, it is possible that previous associations represented epiphenomenon rather than links between metabolic disorders and cognition (Valcour et al. 2006). Inconsistencies from more recent work could be clarified with assessments completed in a larger cohort during the proximal cART era.

The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) is a longitudinal cohort of HIV-infected and uninfected women and has a multiracial constitution, generally lower levels of education than other cohorts and more individuals with high body mass index (BMI) (Bacon et al. 2005; Barkan et al. 1998; Boodram et al. 2009). In a previous retrospective analysis using a brief neuropsychological testing battery limited to three tests; we identified worse performance associated with higher HOMA on the Stroop Color Naming task, a test of psychomotor speed (Valcour et al. 2012). In 2009, a more comprehensive one-hour battery was added to the core WIHS visits where concurrent fasting blood sampling occurred. This afforded an opportunity for a more comprehensive assessment of cognitive subdomains in relation to IR and an assessment of whether these associations remained in the proximal cART era.

METHODS

Subject selection

The WIHS is a multicenter longitudinal observational cohort of HIV-infected and uninfected women who, during the time of this study, were enrolled from one of six U.S. sites: New York (Bronx and Brooklyn), California (Los Angeles and San Francisco), Washington DC, and Chicago. Women initially enrolled in the WIHS had to be able to attend an outpatient study visit. All subjects signed Institutional Review Board-approved consent forms.

An extended neuropsychological testing battery was added to the WIHS exam beginning in April 2009 and continuing through the first wave of testing which ended in April 2011. Of the active English-speaking WIHS participants (n=1908), 1594 (84%) completed the test battery of whom 1273 had concurrent fasting blood work within the prior 6 months. Subjects were excluded from this analysis for: a) presence of conditions that limit test validity (e.g., hearing loss, impaired vision, immediate influence of illicit substances, n=5); b) history of stroke (n=11); and c) self-reported use of antipsychotic medication in the past 6 months (n=40). Individuals with diabetes, defined as having a self-reported diagnosis, a fasting glucose of over 125 mg/dL, or being on diabetic medications, were analyzed separately (n=237). Thus, we evaluated 994 (659 HIV-infected; 62% of the active cohort) for the insulin resistance analyses.

Cognitive characterization

The neuropsychological battery was designed by neuroAIDS experts to allow future diagnostic characterization using HAND criteria; HAND diagnoses have not been applied to the cohort to date and were therefore not available for these analyses. Our battery included the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT); Stroop Test; Trail Making Test Parts A and B; Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT); Letter Fluency (F, A, S); Semantic Fluency (animals); Grooved Pegboard; and Letter-Number Sequencing Test (LNS). The LNS measures verbal working memory from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV (WAIS IV). For the control condition (attention), the test requires the participants to listen to a list of letters and numbers and then repeat back the string of letters and numbers exactly in the order in which they were stated. For the experimental condition (working memory), the test requires the participant to listen to a list of letters and numbers and then repeat back the numbers in ascending order and the letters in alphabetical order. All testers were internally certified through structured training and quality assurance.

Metabolic and clinical variables

Fasting specimens for glucose determination were collected in tubes with glycolytic inhibitors. Serum for insulin was obtained at the same time and was stored (-70°C) until the day of assay. Plasma glucose was measured using the hexokinase method and insulin was measured using the IMMULITE 2000 assay at a central laboratory (Quest Diagnostics, Baltimore, MD). Insulin resistance was estimated using the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA), defined as (insulin × glucose)/405 with insulin measured in μU/mL and glucose measured in mg/dL (Matthews et al. 1985). We confirmed HIV status by FDA-approved enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with western blot when positive. Plasma HIV RNA levels and CD4 T-lymphocyte counts were completed using standard techniques. Hypertension was defined as having a systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg, and/or self-reported use of anti-hypertensive medications. Heavy alcohol use was defined as reporting >7 drinks per week or more than 4 drinks in one sitting. Hepatitis C was defined using both HCV Ab and HCV RNA levels. Negative for HCV was operationalized as being HCV Ab negative or having absent HCV RNA in those with HCV AB+. Subjects who were HCV AB+ with detectable or untested HCV RNA were coded as HCV positive.

Statistical analyses

We examined demographic characteristics by quartiles of HOMA using ANOVAs for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. We used a regression-based approach to create demographically-corrected normative standards (T-scores) for individual neuropsychological tests, as previously published (Maki Currently Under Review by Journal of Neurology; Rubin et al. 2014). The regression equations were based on the larger sample of WIHS women (N=1521). The Trail Making tests, Stroop, Grooved Pegboard scores and HOMA were skewed and thus log-transformed before inclusion in our models. We took the average of dominant and non-dominant hands for our composite Grooved pegboard measure. In the overall sample, we used multivariable regression analyses to examine the separate and interactive associations of HOMA and HIV status on cognitive performance. The models adjusted for confounders including body mass index; waist-to-hip ratio; fasting cholesterol; marijuana use; crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use; alcohol use; antidepressant medication use; depressive symptoms; HCV infection; income; and study site. We also adjusted for number of prior exposures to the Stroop (range 1-4), HVLT (range 1-2), SDMT (range 1-5), and the Trail Making Test (range 1-5). Interactions between HOMA and HIV status were retained in the final model if p<0.10; stratum-specific estimates within HIV status are reported for interactions. For significant interactions (p<0.05), the final model was re-run for the HIV-infected women only including the additional covariates of recent CD4 count and viral load, nadir CD4 count, and cART use and adherence. Planned exploratory analyses in HIV-infected women were also conducted to examine interactions between HOMA and HIV clinical characteristics (HIV viral load, recent and nadir CD4 count, cART use and adherence. Due to multiple comparisons, we defined significance at the p<0.01 level and trends for p<0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS PROC GENMOD (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

About two thirds of the women were HIV-infected; mean age ranged from 43 to 46 years and women reported completing about 12 years of education (Table 1). Women in the higher quartiles of HOMA were more often HIV-uninfected women (p=0.003). Metabolic parameters also differed by group with the highest HOMA quartile having a higher BMI (33.5 Kg/m2), more hypertension (44%) and a greater waist-hip ratio (0.93). Depression and hepatitis C co-infection were also more common among those in the highest HOMA quartile. Substantial differences in former or current crack, cocaine, heroin, or marijuana use were not identified (data not shown) but those in the highest quartile of HOMA were more likely to report abstaining from alcohol (61%, p=0.01). The women were largely on cART and most were adherent with only 10-20% having plasma HIV RNA levels > 10,000 copies/ml.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the women by quartile of HOMA-IR

| Lowest Quartile | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | Highest Quartile | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMA-IR range | <0.72 | 0.72-1.52 | 1.521-2.81 | >2.81 | |

| Sample size | 248 | 252 | 247 | 247 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.4 (9.0) | 45.2 (9.5) | 45.8 (9.4) | 45.9 (9.1) | 0.01 |

| Years of Education, mean (SD) | 12.5 (3.1) | 12.8 (2.7) | 12.6 (2.8) | 11.9 (3.0) | 0.01 |

| WRAT-R, mean (SD) | 91.9 (19.0) | 93.2 (15.8) | 92.5 (17.8) | 88.5 (18.7) | 0.02 |

| Race, % | 0.16 | ||||

| African-American, non-Hispanic | 66% | 67% | 70% | 62% | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 12% | 13% | 8% | 9% | |

| Hispanic | 20% | 16% | 18% | 26% | |

| Other | 2% | 4% | 4% | 3% | |

| HIV status, %HIV-uninfected | 22% | 24% | 26% | 28% | 0.003 |

| CES-D ≥16, % | 28% | 23% | 28% | 35% | 0.03 |

| Hepatitis C positive, % | 10% | 18% | 19% | 24% | 0.001 |

| Metabolic Parameters | |||||

| BMI, mean+SD | 25.9 (6.1) | 28.8 (6.8) | 31.2 (7.3) | 33.5 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 29% | 33% | 34% | 44% | 0.005 |

| Smoking status, % | 0.80 | ||||

| Never | 26% | 31% | 28% | 26% | |

| Former | 47% | 41% | 42% | 43% | |

| Recent | 27% | 28% | 30% | 31% | |

| Fasting Chol. mg/dl, mean (SD) | 173.6 (32.8) | 178.5(38.3) | 180.7(39.9) | 179.4 (37.6) | 0.17 |

| MAP, mean (SD) | 89.8 (13.4) | 91.0 (13.1) | 90.9 (12.4) | 91.4 (12.8) | 0.53 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.87+0.07 | 0.89+0.07 | 0.91+0.07 | 0.93+0.07 | <0.001 |

| Recent Alcohol use, % | 0.01 | ||||

| Abstainer | 46% | 52% | 55% | 61% | |

| Not heavy | 25% | 29% | 24% | 23% | |

| Heavy | 29% | 19% | 21% | 16% | |

| cART >95% compliance | 60% | 61% | 68% | 68% | |

| CD4 count, % | 0.60 | ||||

| >500 | 47% | 47% | 54% | 52% | |

| 200-500 | 36% | 41% | 31% | 35% | |

| <200 | 16% | 12% | 15% | 13% | |

| Plasma HIV RNA, % | 0.03 | ||||

| Undetectable | 47% | 50% | 56% | 61% | |

| <10,000 | 35% | 40% | 29% | 25% | |

| ≥10,000 | 18% | 10% | 15% | 14% |

Note. WRAT-R = Wide Range Achievement Test Scaled Score. “Recent” refers to within 6 months of the most recent WIHS visit. “Former” refers to any previous use, but not in the past 6 months.

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; MAP = mean arterial pressure.

In unadjusted models, increasing HOMA was significantly associated with poorer cognitive test performance on Stroop trials 1 and 2, phonemic fluency, Grooved Pegboard, and LNS attention (p’s<0.01; Table 2). Trend level associations were noted on HVLT recognition, Stroop trial 3, and SDMT (p’s<0.05). After adjustment, increasing HOMA remained significantly inversely associated with performance on LNS attention (β= -0.10, p<0.01) and HVLT recognition (β=-0.10, p<0.01) with weaker but statistically significant level associations remaining on phonemic fluency (β=-0.09, p=0.02).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate models for cognitive outcomes associated with HOMA (log)

| n | Estimated effect (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Model | Multivariable Model | ||

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test | |||

| Total Trials 1-3 | 987 | -0.29 (-0.96 to 0.38) | -0.35 (-1.14 to 0.43) |

| Delayed free recall | 987 | -0.19 (-0.86 to 0.47) | -0.12 (-0.91 to 0.67) |

| Recognition | 986 | -1.01 (-1.80 to -0.21)* | -1.29 (-2.24 to -0.33)** |

| Stroopa | |||

| Trial 1&2 | 979 | -1.28 (-2.04 to -0.52)*** | -0.82 (-1.70 to 0.07)† |

| Trial 3 | 949 | -1.00 (-1.88 to -0.12)* | -0.66 (-1.70 to 0.38) |

| Trail Making Testa | |||

| A | 989 | -0.26 (-0.96 to 0.44) | -0.79 (-1.60 to 0.02)† |

| B | 964 | -0.34 (-1.06 to 0.38) | -0.72 (-1.56 to 0.12)† |

| Symbol Digit | 984 | -0.68 (-1.35 to -0.02)* | -0.60 (-1.40 to 0.19) |

| Fluency | |||

| Phonemic | 983 | -1.14 (-1.86 to -0.42)** | -1.06 (-1.91 to -0.21)* |

| Semantic | 985 | -0.34 (-1.01 to 0.32) | -0.57 (-1.34 to 0.21) |

| Grooved Pegboarda | 958 | -1.21 (-1.90 to -0.52)*** | -0.82 (-1.64 to 0.002)† |

| Letter Number Sequencing | |||

| Attention | 882 | -1.08 (-1.84 to -0.31)** | -1.22 (-2.09 to -0.35)** |

| Working memory | 852 | -0.73 (-1.54 to 0.09)† | -0.60 (-1.54 to 0.34) |

0.05<p<0.10;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Log-transformed scores were used. Variables included in the multivariable models included: site, HIV status, alcohol use, body mass index, hypertension, Waist-to-hip ratio, hepatitis C, CES-D, antidepressant medication, fasting cholesterol, marijuana and crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use. For the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Trail Making Test, Symbol Digit, and Stroop we also controlled for the number of times a woman was exposed to the test.

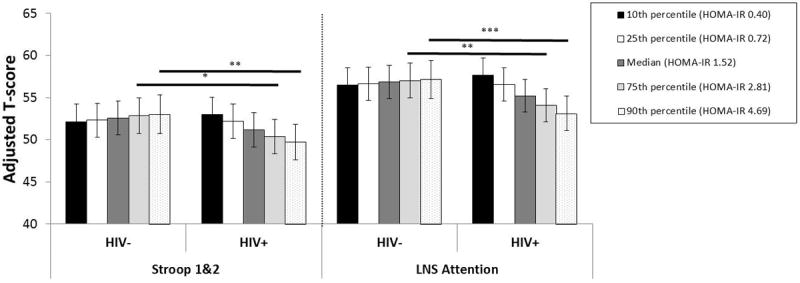

We investigated the possibility that HIV status modified the association of HOMA on cognitive test performance. In these analyses, we found a HOMA and HIV status interaction effect on LNS attention (p=0.01) and on Stroop Trial 1 and 2 (p=0.04)(Figure 1). Specifically, among women with HOMA of 2.81 or greater, HIV-infected women performed significantly worse than uninfected women on LNS attention and Stroop Trial 1 and 2. In multivariable analyses of HIV-infected women only, increasing HOMA was significantly associated with poorer performance on LNS attention (β=-0.15, p=0.001) and Stroop trial 1 and 2 (β=-0.10, p=0.02) even after controlling for disease characteristics such as CD4 count, viral load, cART medication use, and duration of ART.

Fig. 1. Interaction effects by serostatus for Stroop 1 and 2 tasks combined and for Letter Number Sequencing attention task.

There is a decreasing t-score with higher quartile of HOMA-IR in HIV-infected women (declining bar height) that is not seen in HIV-uninfected women. *p<0.05; **p<0.01

Exploratory analyses examined whether HOMA interacted with any HIV clinical characteristics on LNS attention and Stroop Trial 1 and 2. There was a significant interaction between HOMA and nadir CD4 count on Stroop Trial 1 and 2 (p=0.04) after adjusting for other clinical characteristics. In follow-up analyses HOMA was negatively associated with Stroop Trial 1 and 2 performance in HIV-infected women with nadir CD4 counts >200 cells/μl (p<0.01). No other significant interactions were noted on either Stroop Trial 1 and 2 or LNS attention

We completed a separate analysis to determine if having diabetes was associated with worse performance on individual tests (Table 3). Here, isolated effects were identified on one test of manual dexterity/psychomotor speed (grooved pegboard test), noting that diabetes was associated with worse performance on this timed measure.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate models for cognitive outcomes associated with diabetes

| n | Estimated effect (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Model | Multivariable Model | ||

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test | |||

| Total Trials 1-3 | 1209 | 0.82 (-0.62 to 2.27) | 0.77 (-0.77 to 2.31) |

| Delayed free recall | 1209 | 0.57 (-0.88 to 2.01) | 0.51 (-1.03 to 2.06) |

| Recognition | 1208 | 0.14 (-1.58 to 1.86) | 0.27 (-1.59 to 2.13) |

| Stroopa | |||

| Trial 1&2 | 1197 | -1.31 (-2.97 to 0.35) | -0.11 (-1.87 to 1.65) |

| Trial 3 | 1156 | -1.99 (-3.87 to -0.10)* | -0.82 (-2.85 to 1.21) |

| Trail Making Testa | |||

| A | 1209 | -0.52 (-2.04 to 0.99) | -0.80 (-2.41 to 0.81) |

| B | 1177 | -0.22 (-1.78 to 1.35) | -0.22 (-1.87 to 1.43) |

| Symbol Digit | 1203 | -0.39 (-1.82 to 1.04) | -0.03 (-1.57 to 1.51) |

| Fluency | |||

| Phonemic | 1204 | -0.85 (-2.37 to 0.68) | -0.02 (-1.66 to 1.61) |

| Semantic | 1206 | 0.49 (-0.95 to 1.93) | 0.11 (-1.41 to 1.63) |

| Grooved Pegboarda | 1168 | -2.71 (-4.26 to -1.16)*** | -1.75 (-3.42 to -0.09)* |

| Letter Number Sequencing | |||

| Attention | 1071 | -0.12 (-1.77 to 1.52) | 0.07 (-1.66 to 1.80) |

| Working memory | 1038 | 0.10 (-1.64 to 1.84) | -0.02 (-1.87 to 1.83) |

Note.

p<0.05.

Log-transformed scores were used. Variables included in the adjusted models included: site, HIV status, alcohol use, body mass index, hypertension, Waist-to-hip ratio, hepatitis C, CES-D, antidepressant medication, fasting cholesterol, marijuana and crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use. For the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Trail Making Test, Symbol Digit, and Stroop we also controlled for the number of times a woman was exposed to the test.

DISCUSSION

HIV-infection in the current treatment era has been linked to conditions that are HIV-associated, but not necessarily directly due to infection itself (Justice and Braithwaite 2012). These conditions increase in frequency with age and have emerged to have a greater influence on mortality than HIV-associated events (Palella et al. 2006). Similarly, cognitive impairment among individuals with access to treatment is influenced by both HIV-related and unrelated factors. (Clifford and Ances 2013) In a recent multicenter study, the probability of cognitive impairment increased from less than 30% among cases without confounding or contributing factors to nearly 80% among those with such conditions, including head trauma or cerebrovascular events (Heaton et al. 2010).

In the present work, we confirm contributions to cognitive impairment from metabolic factors by identifying an influence of both IR and DM on neuropsychological test performance. Our work adds further support for HIV-unrelated factors contributing to cognitive abilities in the current treatment era. We extend our past work by identifying an HIV-related modulation in the effect of insulin resistance where effects are noted only among HIV-infected women. It is possible that this modulation is not specific to HIV, but instead represents an enhanced vulnerability when a second cognitive syndrome exists, in this case, that related to HIV infection; but, exploratory analyses suggest a stronger effect among patients without low CD4 nadir counts, somewhat contrary to this hypothesis. Past work in HIV-uninfected populations have predominantly isolated associations in those with Mild Cognitive Impairment or early Alzheimer’s disease (Craft and Watson 2004). This is supported by our findings of strongest effects in attention measures, known to be associated with HIV.

A number of factors were noted to differ in the group with the highest levels of HOMA, including metabolic factors (BMI, hypertension) and hepatitis C. This group was also more likely to abstain from alcohol use, a possible reflection of current or past hepatitis C, and thus counseling to reduce further injury to the liver, or past Alcohol use, although we noted no difference in rates for self-reported past treatment for alcoholism in those currently abstaining compared to non-abstainers among individuals where that information was available (p=0.20, n= 474). Although our models adjusted for these variables, this finding remains of interest. It may not be possible to completely adjust for these factors, raising suspicion that IR reflects a more global picture of metabolic and hepatic dysfunction being detrimental to cognition in the current HIV treatment era.

Our work utilized internal controls to develop t-scores, an approach that strengthens our ability to isolate HIV-specific effects, as WIHS HIV-uninfected women were enrolled because of similar risk behaviors. However, it limits our ability to interpret the magnitude of HOMA effects external to the WIHS, since our t-scores would not be expected to match those from published norms or be similar for the general population. This issue is highlighted in figure 3, where average performance appears to be greater than 50, due to women contributing to this analysis having slightly higher performance than the full WIHS HIV-uninfected women (not that of the general population represented in published normative data tables).

In summary, we identify an association between insulin resistance and, separately, diabetes with neuropsychological testing performance in cohort of women who have access to cART and who, in large part, are adherent to treatment. These data confirm an influence of metabolic derangements in the current treatment era and provide further evidence that factors not specific to HIV continue to influence cognition.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Dr. Rubin’s efforts are supported by 1K01-MH098798. Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Michael Saag, Mirjam-Colette Kempf, and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Howard Minkoff and Deborah Gustafson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Mary Young), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Margaret Fischl and Lisa Metsch), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Alexandra Levine and Marek Nowicki), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I – WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA) and UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors, Victor Valcour M.D., Ph.D., Leah H. Rubin Ph.D., Phyllis Tien M.D., Kathryn Anastos M.D., Mary Young M.D., Wendy Mack Ph.D., Mardge Cohen M.D., Elizabeth T. Golub Ph.D., Howard Crystal M.D., and Pauline M. Maki Ph.D., declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclosures: The authors have no disclosures

References

- Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, Gange S, Barranday Y, Holman S, Weber K, Young MA. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(9):1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, Young M, Greenblatt R, Sacks H, Feldman J. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boodram B, Plankey MW, Cox C, Tien PC, Cohen MH, Anastos K, Karim R, Hyman C, Hershow RC. Prevalence and correlates of elevated body mass index among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(12):1009–1016. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdo TH, Weiffenbach A, Woods SP, Letendre S, Ellis RJ, Williams KC. Elevated sCD163 in plasma but not cerebrospinal fluid is a marker of neurocognitive impairment in HIV infection. AIDS. 2013;27(9):1387–1395. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32836010bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford DB, Ances BM. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(11):976–986. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70269-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft S, Watson GS. Insulin and neurodegenerative disease: shared and specific mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(3):169–178. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00681-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I C. Group. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, Braithwaite RS. Lessons learned from the first wave of aging with HIV. AIDS. 2012;26(Suppl 1):S11–18. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283558500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutchan JA, Marquie-Beck JA, Fitzsimons CA, Letendre SL, Ellis RJ, Heaton RK, Wolfson T, Rosario D, Alexander TJ, Marra C, Ances BM, Grant I C. Group. Role of obesity, metabolic variables, and diabetes in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Neurology. 2012;78(7):485–492. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182478d64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palella FJ, Jr, Baker RK, Moorman AC, Chmiel JS, Wood KC, Brooks JT, Holmberg SD H. I. V. O. S. Investigators. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(1):27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Sundermann EE, Cook JA, Martin EM, Golub ET, Weber KM, Cohen MH, Crystal H, Cederbaum JA, Anastos K, Young M, Greenblatt RM, Maki PM. Investigation of menopausal stage and symptoms on cognition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Menopause. 2014 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasa S, Grinspoon SK. Metabolic and body composition effects of newer antiretrovirals in HIV-infected patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(5):R185–202. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi V, Balestra P, Bellagamba R, Corpolongo A, Salvatori MF, Visco-Comandini U, Vlassi C, Giulianelli M, Galgani S, Antinori A, Narciso P. Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits despite long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-related neurocognitive impairment: prevalence and risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(2):174–182. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318042e1ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcour V, Maki P, Bacchetti P, Anastos K, Crystal H, Young M, Mack WJ, Cohen M, Golub ET, Tien PC. Insulin resistance and cognition among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adult women: the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28(5):447–453. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcour VG, Ananworanich J, Agsalda M, Sailasuta N, Chalermchai T, Schuetz A, Shikuma C, Liang CY, Jirajariyavej S, Sithinamsuwan P, Tipsuk S, Clifford DB, Paul R, Fletcher JL, Marovich MA, Slike BM, DeGruttola V, Shiramizu B, Team SP. HIV DNA reservoir increases risk for cognitive disorders in cART-naive patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcour VG, Sacktor NC, Paul RH, Watters MR, Selnes OA, Shiramizu BT, Williams AE, Shikuma CM. Insulin resistance is associated with cognition among HIV-1-infected patients: the Hawaii Aging With HIV cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(4):405–410. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243119.67529.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]