Abstract

A natural tolerance of various environmental stresses is typically supported by various cytoprotective mechanisms that protect macromolecules and promote extended viability. Among these are antioxidant defenses that help to limit damage from reactive oxygen species and chaperones that help to minimize protein misfolding or unfolding under stress conditions. To understand the molecular mechanisms that act to protect cells during primate torpor, the present study characterizes antioxidant and heat shock protein (HSP) responses in various organs of control (aroused) and torpid gray mouse lemurs, Microcebus murinus. Protein expression of HSP70 and HSP90α was elevated to 1.26 and 1.49 fold, respectively, in brown adipose tissue during torpor as compared with control animals, whereas HSP60 in liver of torpid animals was 1.15 fold of that in control (P < 0.05). Among antioxidant enzymes, protein levels of thioredoxin 1 were elevated to 2.19 fold in white adipose tissue during torpor, whereas Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase 1 levels rose to 1.1 fold in skeletal muscle (P < 0.05). Additionally, total antioxidant capacity was increased to 1.6 fold in liver during torpor (P < 0.05), while remaining unchanged in the five other tissues. Overall, our data suggest that antioxidant and HSP responses are modified in a tissue-specific manner during daily torpor in gray mouse lemurs. Furthermore, our data also show that cytoprotective strategies employed during primate torpor are distinct from the strategies in rodent hibernation as reported in previous studies.

Keywords: Heat shock proteins, Antioxidant capacity, Primate hypometabolism, Stress response

Introduction

Survival in the face of unfavourable environmental conditions is a challenge for most animals. For instance, animal fitness is often limited by fluctuations in the availability of basic nutrients as well as by abiotic stresses (too hot, too cold, or too dry climate, low oxygen, etc.). When faced with environmental stresses, many animals exhibit adaptive responses that provide cytoprotection to combat potential damage to cells [1]. Changes in ambient temperature are among the most common stressors experienced by animals, which can often disrupt metabolic homeostasis. Such disruption can occur via a number of mechanisms including direct temperature effects on enzyme properties, protein conformation, and lipid fluidity, as well as secondary consequences such as changes in reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Many animals that must deal with extreme changes in temperature on a seasonal basis use strong metabolic rate depression to enter a torpid or dormant state when temperature is too cold (or too hot). They couple metabolic rate depression with enhanced cytoprotection, such as elevated levels of chaperones that help stabilize protein structure/function, as well as antioxidant defenses to deal with oxidative stress while in the hypometabolic state [2–4].

One of the hallmark responses to high temperature stress is the induction of heat shock proteins (HSPs), a group of chaperone proteins that function to aid proteome stability [5]. However, HSPs are now well known to be induced by many abiotic stresses that disrupt the cellular proteome, such as hypoxia, ischemia, oxidative stress, heavy metals, UV radiation, and low temperature [6,7]. HSP protein family members are named according to their molecular weight and the best known HSP proteins include HSP27, HSP40, HSP60, HSP70, HSP90α, and HSP110. Moreover, the family now includes many other chaperone proteins [8,9]. Although different HSPs respond to different cellular cues, their primary function is to maintain proteome stability, by guiding the folding of nascent proteins, re-folding misfolded proteins, preventing protein aggregation, and directing the degradation of unstable proteins [10,11]. HSP induction is a known component of metabolic rate depression in many systems, supporting long-term survival in hypometabolic states including dormancy, torpor, aestivation, and diapause. For example, the expression of HSP10, 60, 90, and 110 was all upregulated in the hepatopancreas following 14 days of estivation in snails (Otala lactea) [7], whereas expression of HSP70 and HSP27 (and its phosphorylated form) was upregulated in skeletal muscle of hibernating bats (Myotis lucifugus) [12,13].

Entry into hypometabolic states can also cause fluctuations to aerobic metabolism, leading to altered ROS production and potential oxidative damages [14]. This is particularly prominent in mammalian hibernation, since two factors come into play. First, intermittent arousals from torpor necessitate a huge increase in oxygen uptake and consumption (with a proportional increase in ROS generation) to power the thermogenesis required to rewarm the body to euthermia. Second, to maintain fluidity of lipid fuel depots at the low body temperature (Tb) during hibernation requires an increase in their polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) content, which is highly susceptible to lipid peroxidation [15,16]. Hence, antioxidant defenses are necessary during the hibernation. These are provided by both low molecular weight metabolic antioxidants as well as antioxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, peroxiredoxin (PRX), thioredoxin (TRX), glutathione peroxidase, and other glutathione-linked enzymes [17,18].

Recent studies have presented the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) as a new model for the study of primate adaptation to environmental stress [19]. These small primates utilize daily or multi-daily torpor, reducing their metabolic rate (a maximum of ∼ 80% reduction compare to resting metabolic rate recorded) in order to cope with unfavourable conditions during the dry season in Madagascar, when food and water are limited and ambient temperatures are reduced [19]. Previous studies have shown that under short-day conditions combined with food restriction, gray mouse lemurs showed evidence of higher oxidative stress associated with increased torpor expression [20]. To date, little is known about the cytoprotective responses of lemurs during torpor. We hypothesized that during torpor, lemurs activate endogenous defense mechanisms to alleviate cellular stress, potentially using similar mechanisms as observed during torpor in well-studied mammalian hibernators (e.g., bats and ground squirrels) [12,13,21–23]. To test this hypothesis, we examined the expression of proteins involved in the heat shock response and antioxidant defense in lemurs during daily torpor to identify potential molecular mechanisms of the stress response in primate torpor.

Results

Expression of HSPs during torpor

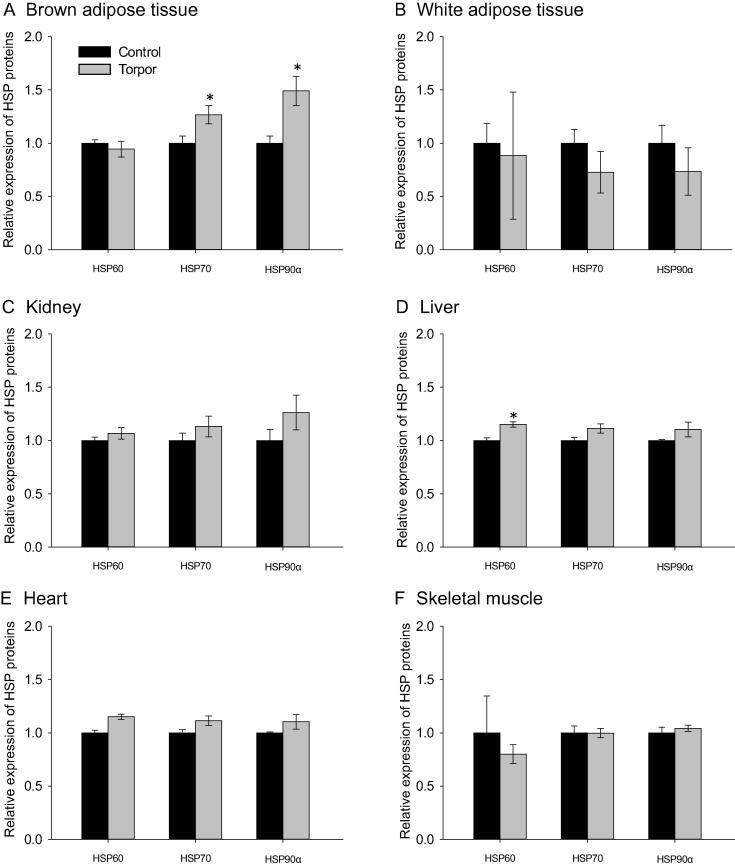

We first examined the expression of three major heat shock proteins (HSP60, HSP70, and HSP90α) in control (aroused) and torpid animals. Multiplex assay was employed to evaluate the protein expression in lemur tissues including the liver, muscle, heart, kidney, white adipose tissue (WAT), and brown adipose tissue (BAT). As shown in Figure 1, expression of HSP70 and HSP90α in BAT was significantly higher during torpor as compared to control animals; which was 1.27 ± 0.08 fold and 1.49 ± 0.14 fold, respectively (P < 0.05) (Figure 1A). Significantly higher amount of HSP60 was only observed in the liver during torpor (1.15 ± 0.02 fold, compared to control; P < 0.05) (Figure 1D). Otherwise, the expression of HSPs were comparable between control and torpor states in the WAT (Figure 1B), kidney (Figure 1C), heart (Figure 1E), and skeletal muscle (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

HSP expression in gray mouse lemurs during daily torpor

Protein expression levels of HSP60, HSP70, and HSP90α were measured in different tissues, comparing control (aroused) and torpid lemurs. Studied tissues include brown adipose tissue (A), white adipose tissue (B), kidney (C), liver (D), heart (E), and skeletal muscle (F). All data were obtained by multiplex analysis using a Luminex 100 instrument and analyzed with Milliplex analyst software. Shown are histograms of median fluorescent intensity (MFI) of immune-reactive multiplex beads ± SEM (n = 4 independent trials for different animals). Data were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test; asterisk denotes significant difference from control (P < 0.05).

Total antioxidant defense during torpor

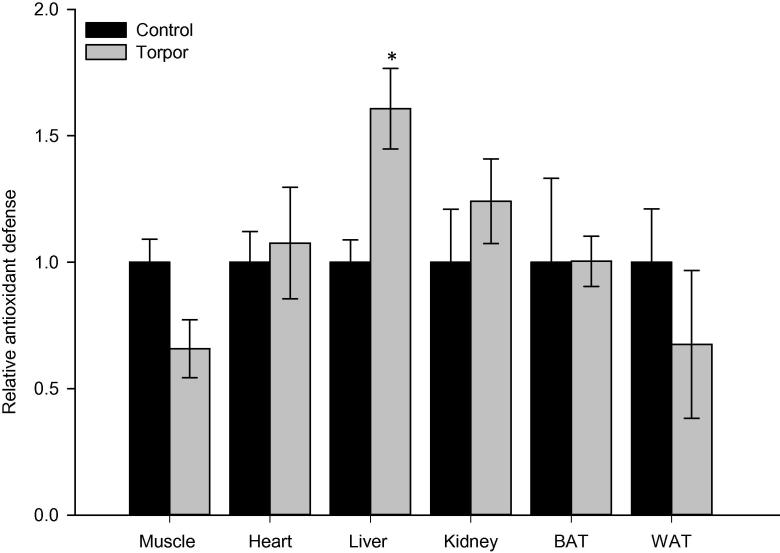

We then evaluated the total antioxidant capacity in six lemur tissues comparing control and torpor conditions (Figure 2). The antioxidant assay kit measures the cumulative antioxidant capacity supplied by a variety of cellular antioxidant molecules including vitamin C, vitamin E, glutathione, bilirubin, albumin, and uric acid. This is accomplished by measuring the rate at which these cellular antioxidant molecules inhibit the metmyoglobin-catalyzed oxidation of 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) to its radical cation form. A significant change in tissue antioxidant capacity was observed only in liver, which is 1.61 ± 0.16 fold in liver of torpid lemurs relative to control (aroused) animals (P < 0.05). Total antioxidant capacity did not change significantly between control and torpid lemurs in any of the other tissues, although antioxidant capacity in skeletal muscle tended to be lower during torpor.

Figure 2.

Total antioxidant capacity in gray mouse lemurs during daily torpor

Antioxidant capacity measured was converted to Trolox equivalents against a Trolox standard curve in six tissues from control and torpid lemurs. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 4 independent trials from different animals). Data were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test; asterisk denotes significant difference from control (P < 0.05).

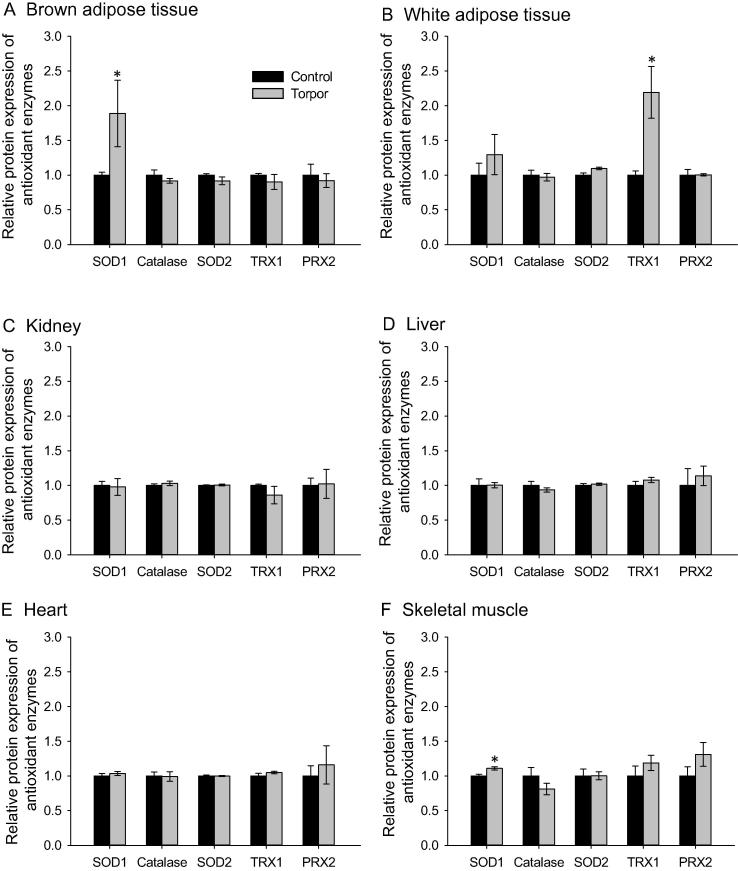

Expression of antioxidant enzymes during torpor

The protein expression levels of five antioxidant enzymes were measured using a Human Oxidative Stress Luminex panel in the six lemur tissues, comparing control (aroused) and torpor states. The five antioxidant enzymes measured in this study are involved in the detoxification of ROS molecules and are crucial to the oxidative stress response. These enzymes include Cu/Zn-SOD1 (the cytoplasmic form), Mn-SOD2 (the mitochondrial form), catalase, thioredoxin 1 (TRX1), and peroxiredoxin 2 (PRX2). Interestingly, expression of the majority of enzymes were comparable between torpor and arousal in most of the tissues examined (Figure 3). Among them, SOD1 the protein expression of cytoplasmic SOD1 was significantly higher in both BAT and skeletal muscle during torpor (Figure 3A and F), which was 1.9 ± 0.47 and 1.1 ± 0.02 fold as compared to control, respectively (P < 0.05). In addition, the expression of TRX1 was significantly higher during torpor (2.19 ± 0.37 fold as compared with control) in WAT (Figure 3B; P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Expression of antioxidant enzymes in gray mouse lemurs during daily torpor

Protein expression of Cu/Zn-SOD1 (SOD1), catalase, mitochondrial Mn-SOD (SOD2), thioredoxin 1 (TRX1), and peroxiredoxin 2 (PRX2) were measured in different tissues from control and torpid lemurs including brown adipose tissue (A), white adipose tissue (B), kidney (C), liver (D), heart (E), and skeletal muscle (F). All data were obtained by multiplex analysis using a Luminex 100 instrument and analyzed with Milliplex analyst software. Shown are histograms of median fluorescent intensity (MFI) of immune-reactive multiplex beads ± SEM (n = 4 independent trials from different animals). Data were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test; asterisk denotes significant difference from control (P < 0.05).

Discussion

To survive in challenging environments, animals often need to display considerable phenotypic plasticity at a metabolic level to adjust their energy demands to the realities of fuel/energy availability in the environment. To date, it has been well documented that coordinated reductions in energy expenditures on nonessential metabolic processes and a shift toward an altered metabolism that includes multiple cytoprotective mechanisms are hallmarks of stress-induced hypometabolism [1].

The present study focuses on these two classes of cytoprotective proteins to analyze their roles in lemur torpor. Interestingly, we found that expression of HSPs was mostly unchanged during torpor, with significant upregulation of selected HSPs observed only in BAT and liver (Figure 1). Elevated expression of HSP70 and HSP90α in BAT is particularly interesting, since this tissue produces heat through non-shivering thermogenesis (NST) to rewarm animals during arousal back to euthermia [24–27]. Previous studies have shown that gene and protein expression of HSP70 was upregulated in BAT of Sprague–Dawley rats during cold exposure, in parallel with the induction of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), suggesting a specific role for HSPs in this thermogenic organ [28]. Thermogenesis in BAT arises from uncoupling ATP synthesis from the electron transport chain in the mitochondria, which requires the expression of UCP1 [25–28]. In lemurs, expression of UCP1 is also upregulated in BAT to support NST during torpor and/or arousal [25]. HSP70, along with HSP90α, also functions as a molecular chaperone in the mitochondria to promote translocation and folding of mitochondrial proteins [29,30]. Upregulation of HSP70 and HSP90α could contribute to ensuring proper folding of UCP1 in the mitochondria, as an aid to NST during torpor in the lemur [28,29], and/or aid overall maintenance of the active conformations of proteins in the face of rapidly-rising temperatures in BAT during active NST.

Compared to the other tissues studied, expression of HSP60 was significantly upregulated only in the liver during torpor, albeit to a minor extent (Figure 1). HSP60 is a mitochondrial chaperone and plays a crucial role in regulating cell survival in response to increased levels of iron-dependent oxidative stress [31]. Previous studies showed that peroxide levels were elevated in HSP60-depleted cells, while elevated expression of HSP60 led to greater cellular resistance against H2O2 and superoxide anions [31]. Additionally, recent studies have also shown that upregulation of HSP60 expression is linked to chemically-induced ROS elevation in Drosophila, as well as type-2 diabetes associated oxidative stress in HeLa cells [32,33]. Therefore, the upregulation of HSP60 in lemur torpor could function similarly in regulating ROS resistance. The expression of HSP60 is also elevated during hibernation of ground squirrels, with previous microarray screening studies showing putative up-regulation of HSP40, HSP60, and HSP70 in liver during torpor [34]. Although the exact role of HSP60 in regulating oxidative stress is not fully understood, this link is not surprising due to the role of HSP60 in regulating mitochondrial protein import and folding [35].

To better understand the state of oxidative stress in lemur tissues during torpor, the total antioxidant capacity of six tissues was measured, along with expression levels of five antioxidant enzymes. An increase in total antioxidant capacity was observed in liver during torpor, but there were no significant changes in other tissues including BAT. The increase in liver antioxidant capacity may be indicative of a potential increase in oxidative stress during torpor. Interestingly, such increased antioxidant capacity was correlated with the elevated HSP60 expression, which was also seen in liver during torpor. Recent studies have also shown that the protein expression of SOD1 and catalase are elevated in some of tissues during hibernation of ground squirrels as compared to euthermic controls [21,36,37]. We observed limited changes in the protein levels of antioxidant enzymes across the six tissues during lemur torpor, with significant upregulation observed only for TRX1 in WAT and SOD1 in skeletal muscle and BAT. The general lack of change in the protein expression levels of antioxidant enzymes was intriguing; however, it should be noted that the antioxidant capacity of the tissue is the real measure of their functionality during torpor.

Conclusion

The data presented in this study show that selected similarities in cytoprotective mechanisms occur between primate and rodent torpor, for example, activation of HSPs such as HSP60 in BAT and HSP70 in liver. However, in terms of antioxidant response, it appears that the transcriptional activation and increased synthesis of antioxidant enzymes are not the major responsive events in lemur torpor. This is in contrast to previous findings in ground squirrel torpor, with evidence of upregulation of PRX in the BAT and the heart during torpor, catalase in the skeletal muscle, and both SOD1 and SOD2 in BAT in response to torpor [21,38]. It is likely that the difference in duration and depth of torpor could differentially influence the transcriptional responses observed between torpid lemurs and hibernating ground squirrels. Ground squirrel torpor bouts can last for 3–25 days during the hibernation season, whereas lemur average daily torpor is just 8–15 h [19,39]. The shorter length of metabolic depression in lemur torpor could suggest that other more rapidly-activated mechanisms may be adapted in torpor. Such mechanisms of adaptation may include posttranslational modifications to proteins/enzymes, as is also known for reversible protein phosphorylation in rodent hibernation [40]. In conclusion, our study provides an initial insight into the molecular profiles of the stress response during primate torpor and provides a basis for the future exploration into the cellular mechanisms that are utilized primates to coordinate either daily torpor or seasonal hibernation.

Materials and methods

Animal treatments

A total of 8 female mouse lemurs (2–3 years of age) were used in the experiment. Animals were born in an authorized breeding colony at the National Museum of Natural History (Brunoy, France; European Institution Agreement No. D91-114-1). Protocols used for animal experiments were as described previously, and were carried out by Dr. Martine Perret and the Adaptive Mechanisms and Evolution Team [24,25]. Detailed animal protocols can be found in [41].

Total protein lysate preparation

Sample lysates were prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol for the assay panels used (Luminex, Toronto ON, Canada). Briefly, tissue samples of ∼50 mg were homogenized 1:2 (w/v) with a Dounce homogenizer using the supplied lysis buffer with the addition 1:100 (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Catalog No. PIC003.1, Bioshop, Burlington ON, Canada). Supernatants containing soluble proteins were removed after centrifugation at 4500 × g for 15 min, and protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay. Lysates were normalized to the same concentration and diluted with manufacturer’s assay buffer to a final concentration of 0.6 μg/μl for the oxidative stress panel and to 4.5 ng/μl for the heat shock protein panel.

Luminex multiplex assay

The multiplex immunoassays utilized for this study included the Human Oxidative Stress Magnetic Bead Panel (Catalog No. H0XSTMAG-18K, Millipore, Etobicoke ON, Canada) and the Heat Shock Protein Magnetic Bead 5-Plex Kit (Catalog No. 48-615MAG, Millipore). Luminex assays were performed as instructed by the manufacturer’s protocol, which were described in detail by Biggar et al. [41] in this special issue.

Antioxidant capacity assay

Total antioxidant capacity was measured in control and torpid lemurs using an Antioxidant Assay kit (Catalog No. 709001, Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). This assay determines total cellular antioxidant levels by measuring the rate at which antioxidants in each sample inhibit the metmyoglobin-catalyzed oxidation of 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) to its radical cation form. Frozen tissue samples were homogenized at 1:4 (w/v) in chilled antioxidant assay buffer with the addition of protease inhibitor as per manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants were collected and soluble protein was determined using the Bradford assay. All samples were standardized to the same protein concentration for the following assays. The antioxidant assays were initiated by addition of sample lysate along with metmyoglobin and chromogen as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Antioxidant capacity was then measured at 750 nm and converted to Trolox equivalents (mM/mg wet mass) using a Trolox antioxidant assay standard curve. Total Trolox equivalents were subsequently converted to relative antioxidant levels, by standardizing against the first control lemur sample.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4). All statistical and graphing analyses were performed using Sigmaplot 12.0 software. Statistical test was performed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test, with a significance level of P < 0.05.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the project and to the editing of the manuscript. MP and FP carried out the animal experiments; CWW, KKB, SNT, and JZ conducted biochemical assays. Data analysis and assembly of the draft manuscript was carried out by KBS, CWW, and KKB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet M. Storey for editorial review of the manuscript and Laurine Haro and Philippe Guesnet for technical and material assistance in the preparation of the lemur tissue samples. This work was supported by a Discovery grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (Grant No. 6793) and a grant from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (Grant No. G-14-0005874) to KBS. KBS holds the Canada Research Chair in Molecular Physiology; CWW, KKB, and SNT all held NSERC postgraduate scholarships.

Handled by Jun Yu

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences and Genetics Society of China.

References

- 1.Storey K.B., Storey J.M. Metabolic rate depression in animals: transcriptional and translational controls. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2004;79:207–233. doi: 10.1017/s1464793103006195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joanisse D.R., Storey K.B. Oxidative damage and antioxidants in Rana sylvatica, the freeze-tolerant wood frog. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R545–R553. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.3.R545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey H.V., Sills N.S., Gorham D.A. Stress proteins in mammalian hibernation. Am Zool. 1999;39:825–835. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey H.V., Frank C.L., Seifert J.P. Hibernation induces oxidative stress and activation of NK-kappaB in ground squirrel intestine. J Comp Physiol B. 2000;170:551–559. doi: 10.1007/s003600000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor R.P., Benjamin I.J. Small heat shock proteins: a new classification scheme in mammals. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kregel K.C. Heat shock proteins: modifying factors in physiological stress responses and acquired thermotolerance. J Appl Physiol. 1985;92:2177–2186. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01267.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Storey K.B., Storey J.M. Heat shock proteins and hypometabolism: adaptive strategy for proteome preservation. Res Rep Biol. 2011;2:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampinga H.H., Hageman J., Vos M.J., Kubota H., Tanguay R.M., Bruford E.A. Guidelines for the nomenclature of the human heat shock proteins. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morano K.A., Grant C.M., Moye-Rowley W.S. The response to heat shock and oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190:1157–1195. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.128033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bukau B., Horwich A.L. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell. 1998;92:351–366. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walter S., Buchner J. Molecular chaperones — cellular machines for protein folding. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:1098–1113. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020402)41:7<1098::aid-anie1098>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee K., Park J.Y., Yoo W., Gwag T., Lee J.W., Byun M.W. Overcoming muscle atrophy in a hibernating mammal despite prolonged disuse in dormancy: proteomic and molecular assessment. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:642–656. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eddy S.F., McNally J.D., Storey K.B. Up-regulation of a thioredoxin peroxidase-like protein, proliferation-associated gene, in hibernating bats. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;435:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown J.C., Chung D.J., Belgrave K.R., Staples J.F. Mitochondrial metabolic suppression and reactive oxygen species production in liver and skeletal muscle of hibernating thirteen-lined ground squirrels. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R15–R28. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00230.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank C.L., Storey K.B. The optimal depot fat composition for hibernation by golden-mantled ground squirrels (Spermophilus lateralis) J Comp Physiol B. 1995;164:536–542. doi: 10.1007/BF00261394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank C.L., Karpovich S., Barnes B.M. Dietary fatty acid composition and the hibernation patterns in free-ranging arctic ground squirrels. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2008;81:486–495. doi: 10.1086/589107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermes-Lima M., Zenteno-Savin T. Animal response to drastic changes in oxygen availability and physiological oxidative stress. Comp Biochem Physiol C: Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;133:537–556. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0456(02)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall A., Karplus P.A., Poole L.B. Typical 2-Cys peroxiredoxins — structures, mechanisms and functions. FEBS J. 2009;276:2469–2477. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06985.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid J. Daily torpor in the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) in Madagascar: energetic consequences and biological significance. Oecologia. 2000;123:175–183. doi: 10.1007/s004420051003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giroud S., Perret M., Gilbert C., Zahariev A., Goudable J., Le Maho Y. Dietary palmitate and linoleate oxidations, oxidative stress, and DNA damage differ according to season in mouse lemurs exposed to a chronic food deprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R950–R959. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00214.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vucetic M., Stancic A., Otasevic V., Jankovic A., Korac A., Markelic M. The impact of cold acclimation and hibernation on antioxidant defenses in the ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus): an update. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:916–924. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.08.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Storey K.B. Mammalian hibernation: transcriptional and translational controls. In: Roach R.C., Wagner P.D., Hackett P.H., editors. Hypoxia through the lifecycle. Kluwer/Plenum Academic; New York: 2003. pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan J., Burman A., Nichols C., Alila L., Showe L.C., Showe M.K. Detection of differential gene expression in brown adipose tissue of hibernating arctic ground squirrels with mouse microarrays. Physiol Genomics. 2006;25:346–353. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00260.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giroud S., Blanc S., Aujard F., Bertrand F., Gilbert C., Perret M. Chronic food shortage and seasonal modulation of daily torpor and locomotor activity in the grey mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) Am J Physiol. 2008;294:R1958–R1967. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00794.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Génin F., Nibbelink M., Galand M., Perret M., Ambid L. Brown fat and nonshivering thermogenesis in the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R811–R818. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00525.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scantlebury M., Lovegrove B.G., Jackson C.R., Bennett N.C., Lutermann H. Hibernation and non-shivering thermogenesis in the Hottentot golden mole (Amblysomus hottentottus longiceps) J Comp Physiol B. 2008;178:887–897. doi: 10.1007/s00360-008-0277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barger J.L., Barnes B.M., Boyer B.B. Regulation of UCP1 and UCP3 in arctic ground squirrels and relation with mitochondrial proton leak. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:339–347. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01260.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matz J.M., LaVoi K.P., Moen R.J., Blake M.J. Cold-induced heat shock protein expression in rat aorta and brown adipose tissue. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1369–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altieri D.C. Hsp90 regulation of mitochondrial protein folding: from organelle integrity to cellular homeostasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:2463–2472. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1177-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deshaies R.J., Koch B.D., Werner-Washburne M., Craig E.A., Schekman R. A subfamily of stress proteins facilitates translocation of secretory and mitochondrial precursor polypeptides. Nature. 1988;332:800–805. doi: 10.1038/332800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cabiscol E., Bellí G., Tamarit J., Echave P., Herrero E., Ros J. Mitochondrial Hsp60, resistance to oxidative stress, and the labile iron pool are closely connected in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44531–44538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh M.P., Reddy M.M., Mathur N., Saxena D.K., Chowdhuri D.K. Induction of hsp70, hsp60, hsp83 and hsp26 and oxidative stress markers in benzene, toluene and xylene exposed Drosophila melanogaster: role of ROS generation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;235:226–243. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall L., Martinus R.D. Hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress upregulate HSP60 and HSP70 expression in HeLa cells. Springerplus. 2013;2:431. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Storey K.B. Mammalian hibernation: transcriptional and translational controls. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;543:21–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng M.Y., Hartl F.U., Martin J., Pollock R.A., Kalousek F., Neupert W. Mitochondrial heat-shock protein hsp60 is essential for assembly of proteins imported into yeast mitochondria. Nature. 1989;337:620–625. doi: 10.1038/337620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morin P., Jr, Ni Z., McMullen D.C., Storey K.B. Expression of Nrf2 and its downstream gene targets in hibernating 13-lined ground squirrels, Spermophilus tridecemlineatus. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;312:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9727-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu C.W., Storey K.B. FoxO3a-mediated activation of stress responsive genes during early torpor in a mammalian hibernator. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;390:185–195. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-1969-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin P., Storey K.B. Antioxidant defense in hibernation: cloning and expression of peroxiredoxins from hibernating ground squirrels, Spermophilus tridecemlineatus. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;461:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carey H.V., Andrews M.T., Martin S.L. Mammalian hibernation: cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1153–1181. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storey K.B., Wu C.W. Stress response and adaptation: a new molecular toolkit for the 21st century. Comp Biochem Physiol A: Mol Integr Physiol. 2013;165:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biggar K.K., Wu C.W., Tessier S.N., Zhang J., Pifferi F., Perret M., Storey K.B. Primate torpor: regulation of stress-activated protein kinases during daily torpor in the gray mouse lemur, Microcebus murinus. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]