Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the efficacy of autologous platelet rich plasma (PRP) in regeneration of bone and to assess clinical compatibility of the material in mandibular third molar extraction socket.

Objective of the Study

To compare the healing of mandibular third molar extraction wounds with and without PRP.

Materials and Methods

Group A consists of the 30 patients where PRP will be placed in the extraction socket before closure of the socket. Group B consists of 30 patients who will be the control group where the extraction sockets will be closed without any intra socket medicaments. The patients would be allocated to the groups randomly.

Results

Soft tissue healing was better in study site compared to control site. The result of the study shows rapid bone regeneration in the extraction socket treated with PRP when compared with the socket without PRP. Evaluation for bone blending and trabecular bone formation started earlier in PRP site compared to control, non PRP site. Also there was less postoperative discomfort on the PRP treated side.

Conclusion

Autologous PRP is biocompatible and has significant improved soft tissue healing, bone regeneration and increase in bone density in extraction sockets.

Keywords: Bone density, Bone trabeculae, Mandibular third molar extraction socket, Platelet rich plasma, Soft tissue healing

Introduction

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) is a new and potentially useful adjunct in oral and maxillofacial bone reconstructive surgery. Platelets are very important in the wound healing process. They arrive quickly at the wound site and begin coagulation. They release multiple wound healing growth factors and cytokines, including platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factors (TGF)/β1 and β2, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet derived endothelial cell growth factor (PDEGF), interleukin-1 (IL-1), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and platelet activating factor-4 (PAF-4). These growth factors are thought to contribute to bone regeneration and increased vascularity, vital features of a healing bone graft [1].

It is now well known that platelets have many functions beyond that of hemostasis. Platelets contain important growth factors that, when secreted, are responsible for increasing cell mitosis, increasing collagen production, recruiting other cells to the site of injury, initiating vascular in growth, and inducing cell differentiation. These are all crucial steps in early wound healing. Using the concept that if a few are good, then a lot may be better, increasing the concentration of platelets at a wound may promote more rapid healing. It seems very logical that increasing the concentration of platelets in a bone graft, and therefore increasing the concentration of growth factors, may lead to a more rapid and denser regenerate [2].

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) was first introduced to the oral surgery community by Whitman et al. in their 1997 article entitled “Platelet Gel: An Autologous Alternative to Fibrin Glue With Applications in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.” The authors thought that “through activation of the platelets within the gel and the resultant release of growth factors, enhanced wound healing could be expected.” PRP enjoyed a great increase in popularity in the oral and maxillofacial surgery community after the publication of a landmark article by Marx et al. in 1998. Marx et al.’s [3] study showed that combining PRP with autogenous bone in mandibular continuity defects resulted in significantly faster radiographic maturation and a histomorphometrically denser bone regenerate. It certainly seemed as though a new age in bone grafting had begun.

Materials and Methods

The present study was undertaken at the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Vyas Dental College and Hospital Jodhpur, after obtaining ethical clearance. This study involved both male and female patients, who were referred to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery for removal of mandibular 3rd molar.

Inclusion criteria:

Patients’ age between 18 and 50 years.

Patients who required mandibular 3rd molar extractions.

Exclusion criteria:

Patients with pericoronitis, periapical infection or lesions with respect to impacted 3rd molars.

Opposing traumatic occlusion or impinging upper 3rd molars.

Smokers, alcoholics and patients with any systemic diseases.

Female patients on oral contraceptives.

Those patients with incomplete follow up will be excluded from the study.

After obtaining the complete history, patients were examined clinically and were explained about the procedure, its complications and the follow up period involved in the study. The patients who were willing were enrolled for the study. Informed consent was taken.

Pre-operative radiographic investigation will consist of an OPG or an IOPA radiograph. Group A will consist of the patients where PRP will be placed in the extraction socket before closure of the socket. Group B will be the control group where the extraction sockets will be closed without any intrasocket medicaments. The sample size in each group will consist of 30 patients. The patients would be allocated to the groups randomly. Patient of both the groups will be assessed on day 3, 7 and 14 for dry socket and soft tissue healing. Radiographic assessment for bone healing will be done at 3rd week, 2nd month and 4th month (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

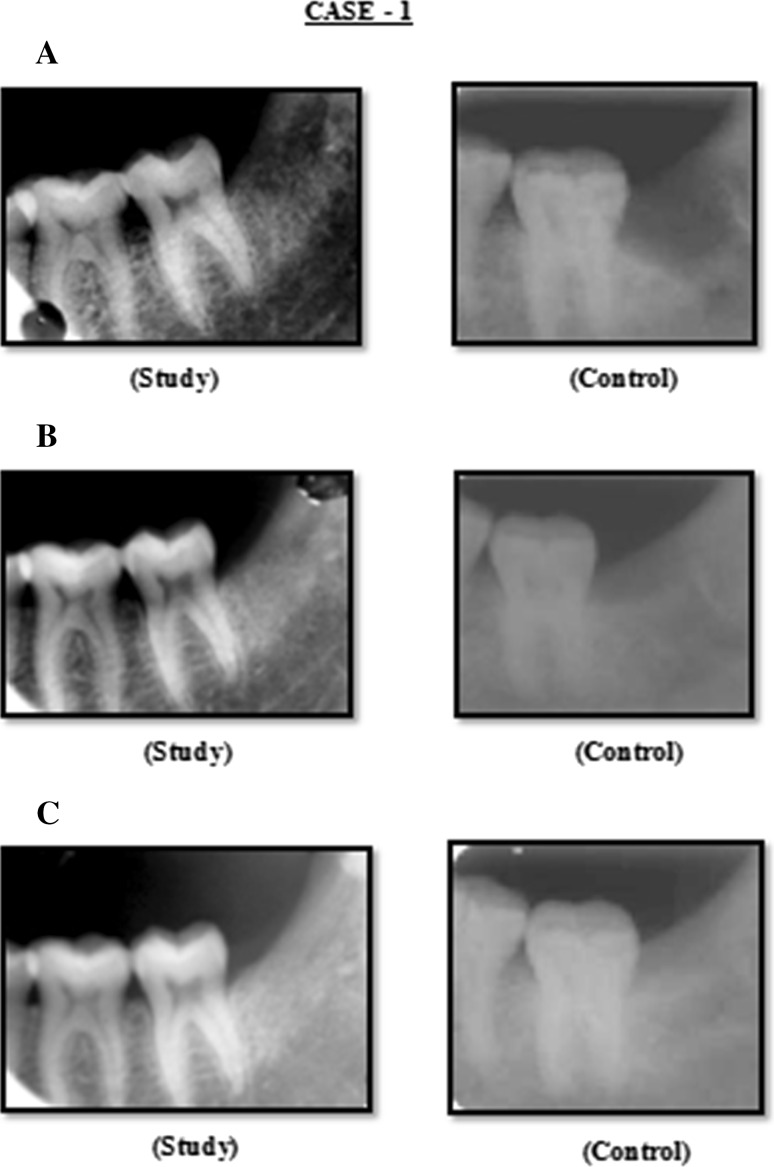

Fig. 1.

Case 1: A Radiograph (IOPA) at 3rd week post operatively, B radiograph (IOPA) at 2nd month post operatively, C radiograph (IOPA) at 4th month post operatively

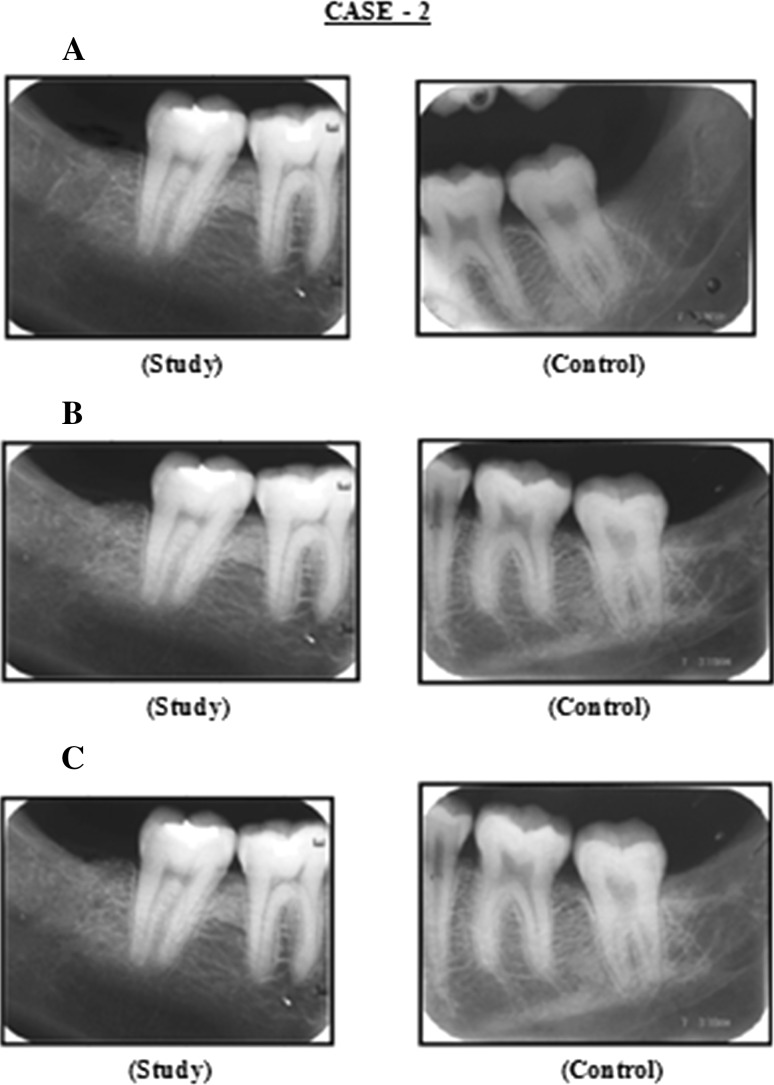

Fig. 2.

Case 2: A Radiograph (IOPA) at 3rd week post operatively, B radiograph (IOPA) at 2nd month post operatively, C radiograph (IOPA) at 4th month post operatively

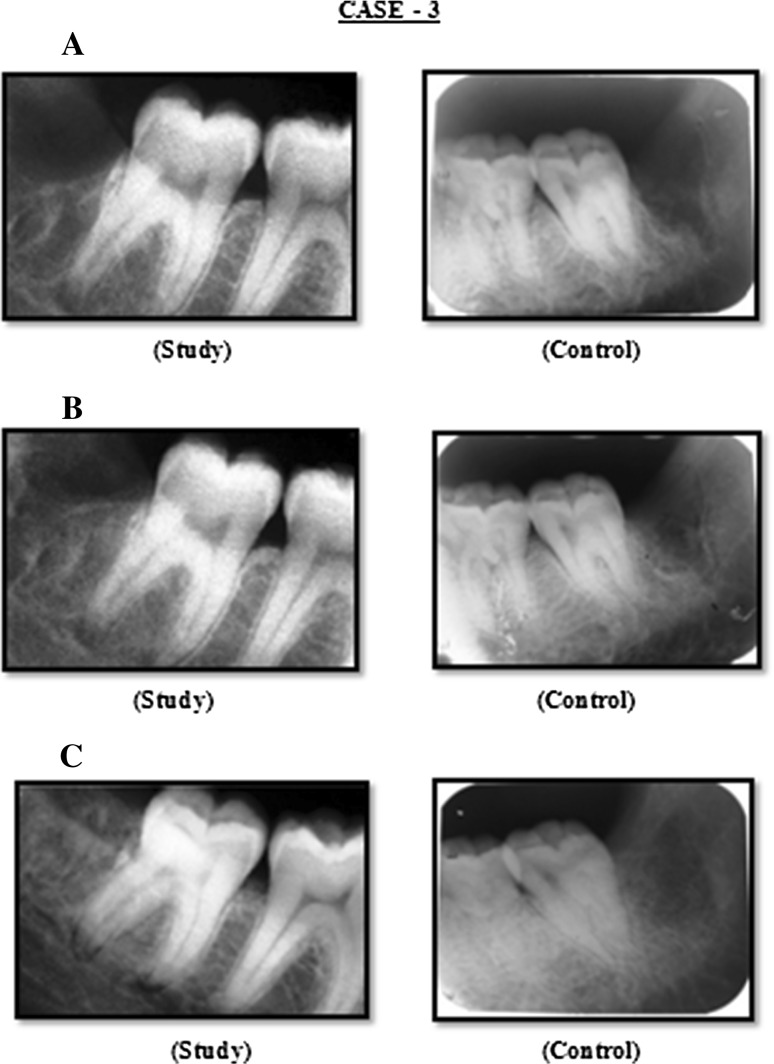

Fig. 3.

Case 3: A Radiograph (IOPA) at 3rd week post operatively, B radiograph (IOPA) at 2nd month post operatively, C radiograph (IOPA) at 4th month post operatively

Clinical Evaluation

Soft tissue healing will be assessed based on the criteria given by Landry et al. [4].

The presence or absence of dry socket will be diagnosed based on Blum’s criteria [5].

Bone healing of the third molar socket will be assessed radiographically using an OPG. The criteria for bone healing and the scoring system will be based on a modification of the Kelley’s method as described by Olufemi et al. [6].

Evaluation of Soft Tissue Healing by Landry et al. and Gonshor [4, 7]

Healing Index 1: Very poor (has 2 or more of the following)

Tissue color: ≥50 % of gingiva red

Response to palpation: bleeding

Granulation tissue: present

Incision margin: not epithelialized, with loss of epithelium beyond incision margin

Suppuration present

Healing Index 2: Poor

Tissue color: ≥50 % of gingiva red

Response to palpation: bleeding

Granulation tissue: present

Incision margin: not epithelialized, with connective tissue exposed

Healing Index 3: Good

Tissue color: ≥25 and <50 % of gingiva red

Response to palpation: no bleeding

Granulation tissue: none

Incision margin: no connective tissue exposed

Healing Index 4: Very good

Tissue color: <25 % of gingiva red

Response to palpation: no bleeding

Granulation tissue: none

Incision margin: no connective tissue exposed

Healing Index 5: Excellent

Tissue color: all tissues pink

Response to palpation: no bleeding

Granulation tissue: none

Incision margin: no connective tissue exposed

Criteria for Dry Socket Assessment Based on Blum’s Criteria [5]

Post operative pain in and around extraction site.

Partially or totally disintegrated blood clot.

With or without halitosis.

With or without necrotic debris.

Denuded socket.

Exudates or pus in the socket.

Mean Radiographic Score for Assessment of Bone Healing at Different Time Points Between Groups [6]

Lamina dura

+2 Lamina dura essentially absent, may be present in isolated areas

+1 Lamina dura substantially thinned, missing in some areas

0 Within normal limits

−1 Portions of lamina dura thickened, milder degrees

−2 Entire lamina dura substantially thickened

Overall density

+2 Severe increase in radiographic density

+1 Mild to moderate increase in radiographic density

0 Within normal limits

−1 Mild to moderate decrease in radiographic density

−2 Severe decrease in radiographic density

Trabecular pattern

+2 All trabeculae substantially coarser

+1 Some coarser trabeculae; milder degrees

0 Within normal limits

−1 Delicate finely meshed trabeculations

−2 Granular, nearly homogenous patterns; individual

trabeculations essentially absent

Preparation of PRP Gel [8–12]

- 1st STEP: Collection of blood (Figs. 4, 5)

- Under all aseptic techniques 5 ml of venous blood will be collected from the anticubital region. 3.6 ml of the collected blood will be placed in a vial containing 0.4 ml CPDA (Citrate Phosphate Dextrose Adenin) anticoagulant solution. The blood will be gently mixed with the anticoagulant. The vials will be thoroughly shaken to ensure mixture of anti coagulant with the drawn blood.

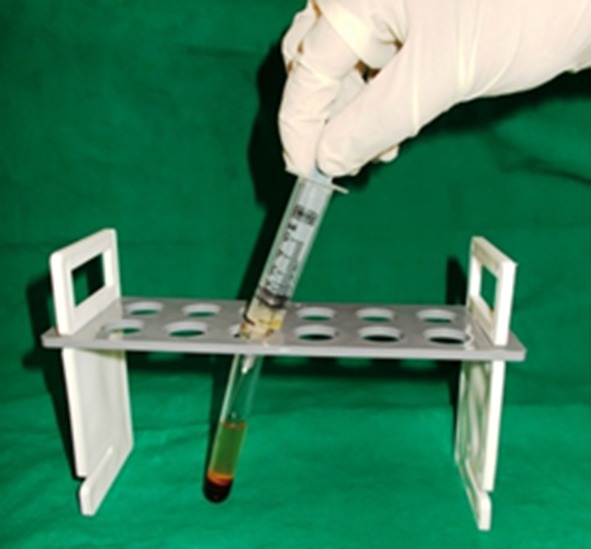

Fig. 4.

Drawing of blood

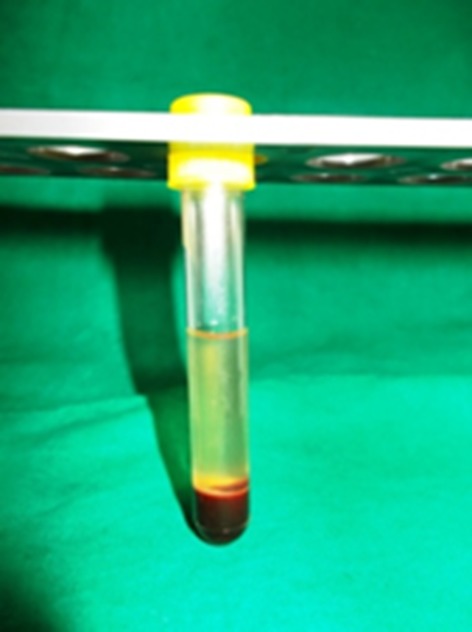

Fig. 5.

Drawn blood in test tube

- 2nd STEP: Preparation of PRP (Figs. 6, 7, 8)

- The tube will be placed in a lab centrifuge machine and counter balanced. The first centrifuge cycle will be done at 2,000 rpm for 15 min. The result will be separation of the whole blood into a lower red blood cell region and upper straw coloured plasma. This plasma contains relatively low concentration of platelets (platelet poor plasma) in the uppermost region and higher concentration of platelets and WBC in the boundary layer often called as ‘Buffy coat’.

- With a micropipette the PPP and the buffy coat layer including 1 mm below the boundary layer will be collected in a sterile test tube and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. After the second centrifuge the upper half will be discarded and the lower half will be used as PRP.

Fig. 6.

Cellular layers separation after 1st spin

Fig. 7.

Cellular layers separation after 2nd spin

Fig. 8.

PPP layers separation after 2nd spin

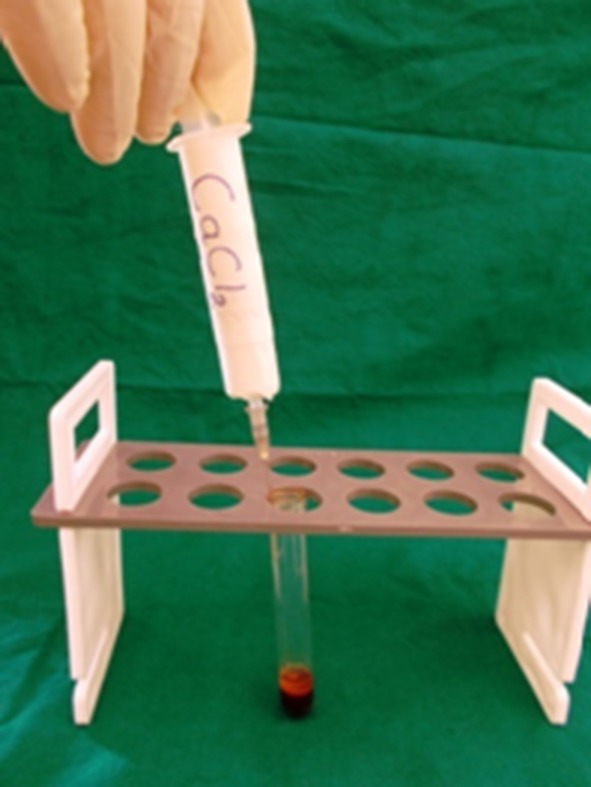

Fig. 9.

PRP before activation

Fig. 10.

PRP activated with CaCl2

Fig. 11.

PRP gel

Fig. 12.

PRP gel placement in extraction socket

Results

After analysis of the data the following observations were made:

In case group there were 30 patients (males 13 and females 17). In control group also there were 30 patients (males 16 and females 14). The patients who had participated in the study were in the age range of 18–50 years, in the study group 33.83 years and in control group 35.30 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Test statistics of age

| Mean | SD | P > .05 | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case group | 33.83 | 8.867 | .604 | No difference |

| Control group | 35.30 | 10.590 |

Results of Clinical Assessment

Clinical Assessment

Test statistic—Pearson Chi Square test

Assessment of healing index of soft tissue:

Assessment of soft tissue healing by 3rd day for case group showed a mean score of 2.50 and for control group 1.87 (P > 0.002). After 7th day for case group mean score was 3.53 and for control group 2.87 (P > 0.001). After 14th day for case group mean score was 4.53 and for control group 3.90 (P > 0.003) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Test statistics of soft tissue healing index

| Group | Mean | SD | P < .05 | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft Tissue Healing index 3rd day | Case group | 2.50 | .572 | .002 | Difference significant |

| Control group | 1.87 | .819 | |||

| Soft Tissue Healing index 7th day | Case group | 3.53 | .571 | .001 | Difference significant |

| Control group | 2.87 | .819 | |||

| Soft Tissue Healing index 14th day | Case group | 4.53 | .571 | .003 | Difference significant |

| Control group | 3.90 | .845 |

Test statistic—Mann–Whitney U test, Wilcoxon W test, Z test.

Radiographic Assessment:

Radiographic assessment at bone healing lamina dura 3rd week for case group showed a mean score of −0.13 and for control group −1.73 (P > 0.000). After 2nd month for case group mean score was 0.87 and control group −0.67 (P > 0.000). After 4th month for case group mean score was 1.87 and control group −0.33 (P > 0.000) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Test statistics of bone healing lamina dura

| Group | Mean | SD | P > .05 | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone healing lamina dura 3rd week | Case group | −.13 | .346 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | −1.73 | .450 | |||

| Bone healing lamina dura 2nd month | Case group | .87 | .346 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | −.67 | .606 | |||

| Bone healing lamina dura 4th month | Case group | 1.87 | .346 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | .33 | .606 |

Bone healing overall density 3rd week for case group showed a mean score of −0.10 and for control group −1.60 (P > 0.000). Bone healing overall density 2nd month for case group the mean score was −0.90 and for control group −0.67 (P > 0.000). Bone healing overall density 4th month for case group the mean score was 1.90 and for control group 0.27 (P > 0.000) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Test statistics of bone healing overall density

| Group | Mean | SD | P > .05 | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone healing overall density 3rd week | Case group | −.10 | .305 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | −1.60 | .770 | |||

| Bone healing overall density 2nd month | Case group | .90 | .305 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | −.67 | .606 | |||

| Bone healing overall density 4th month | Case group | 1.90 | .305 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | .27 | .640 |

Bone healing trabecular pattern 3rd week for case group showed a mean score of −0.17 and for control group −1.63 (P > 0.000). Bone healing trabecular pattern 2nd month for case group the mean score was 0.83 and for control group −0.77 (P > 0.000). Bone healing trabecular pattern 4th month for case group the mean score was 1.83 and for control group −0.10 (P > 0.000) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Test statistics of bone healing trabecular pattern

| Group | Mean | SD | P > .05 | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone healing trabecular pattern 3rd week | Case group | −.17 | .379 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | −1.63 | .809 | |||

| Bone healing trabecular pattern 2nd month | Case group | .83 | .379 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | −.77 | .430 | |||

| Bone healing trabecular pattern 4th month | Case group | 1.83 | .379 | .000 | Difference significant |

| Control group | .10 | .481 |

Discussion

During the last decade, there have been several in vivo animal studies, which have used biological mediators such as polypeptide growth factors to expedite soft tissue and bony healing. It is therefore a reasonable hypothesis that increasing the concentration of platelets in bone defects may lead to improved, faster healing and stimulate new bone formation [13].

Surgical sites enhanced with PRP have been shown to heal at two to three times that of normal surgical sites. PRP can be a great adjunct to many surgical procedures [14], and PRP accelerates wound maturity and epithelialization, hence decreased scar formation. PDGF and epidermal growth factor (EGF) are the main growth factors involved in fibroblast migration, proliferation, and collagen synthesis. Increased concentrations of these growth factors is a likely reason for the accelerated soft tissue wound healing [15].

The PRP is activated to form PRP gel thus causing degranulation of α-granules present in the platelets and releasing the growth factors. The various agents for the activation reported in literature include CaCl2 alone, CaCl2 plus bovine thrombin, human thrombin, autologous bone or whole blood which contains thrombin [16].

In our technique CaCl2 alone was mixed with PRP to form an autologous platelet gel. This platelet gel was free of eliciting any antigen–antibody reaction as it was prepared from patients’ own blood.

Conclusion

The study clearly indicates a definite improvement in the soft tissue healing and faster regeneration of bone after third molar surgery in cases treated with PRP as compared to the control group post operatively. This improvement in the wound healing, decrease in pain, and increase in the bone density signifies and highlights the use of PRP, certainly as a valid method in inducing and accelerating soft and hard tissue regeneration. An added benefit of PRP noted in the present study is its ability to form a biologic gel that provided clot stability and functions as an adhesive. The procedure of PRP preparation is simple, cost effective and has demonstrated good results.

The present study was done with a follow up of 4 months, further clinical trials with longer duration follow up with larger sample size should be done to get more affirmative and conclusive result.

References

- 1.Aghaloo TL, Moy PK, Freymiller EG. Investigation of platelet rich plasma in rabbit cranial defects: a pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:1176–1181. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.34994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freymiller EG, Aghaloo TL. Platelet rich plasma: ready or not? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:484–488. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marx RE. Platelet rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landry RG, Turnbull RS, Howley T. Effectiveness of benzydamyne HCl in the treatment of periodontal post surgical patients. Res Clin Forums. 1988;10:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blum IR. Contemporary views on dry socket (alveolar osteitis): a clinical appraisal of standardization, aetiopathogenesis and management: a critical review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:309–317. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogundipe OK, Ugboko VI. Can autologous platelet rich plasma gel enhance healing after surgical extraction of mandibular third molars? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2305–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonshor A. Technique for producing plarelet rich plasma and platelet concentrate: background and process. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2002;22:547–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robiony M, Polini F, Politi M. Osteogenesis distraction and platelet rich plasma for bone reconstruction of the severely atrophic mandible: preliminary results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:630–635. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.33107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanaman R, Filstein MR, Danesh-Meyer MJ. Localized ridge augmentation using GBR and platelet rich plasma: three case reports. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2001;21:343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell DM, Chang E, Farrior EH. Recovery from deep plane rhytidectomy following unilateral wound treatment with autologous platelet gel: a pilot study. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3(4):245–250. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.3.4.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pradel W, Eckelt U, Lauer G. Radiographic assessment of impacted mandibular third molar socket filled with composite xenogenic bone graft. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2006;35:371–375. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/64880289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smet ED, Jacobs R, Gijbels F, Naert I. The accuracy and reliability of radiographic methods for the assessment of marginal bone level around oral implants. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2002;31:176–181. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon D. Potential for osseous regeneration of platelet rich plasma—a comparative study in mandibular third molar sockets. Ind J Dent Res. 2004;15(4):133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SG, Kim WK, Park JC, Kim HJ. A comparative study of osseointegration of avana implants in a demineralized freeze dried bone alone or with platelet rich plasma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:1018–1025. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.34413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang HL, Avila G. Platelet rich plasma: myth or reality? Eur J Dent. 2007;1(4):192–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsay RC, Jennifer VO, Burke A, Eisig S, Landesberg R. Differential growth factor retention by platelet rich plasma composites. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]