Abstract

Vanishing bone disease (VBD) is a rare disease of unknown etiology which is characterised by progressive replacement of bony framework by proliferation of endothelial lined lymphatic vessels. It has been given numerous names like massive osteolysis, Gorham’s disease, phantom bone disease, and progressive osteolysis. It has no age, sex or race predilection. It may involve single or multiple bones and spread of the disease does not respect the relevant joint as boundary. The first report of the disease was published around two decades back but the mysterious nature of its etiology and ideal management strategy has still not been completely unfolded. The disease may functionally or aesthetically effect the patient and also has the potential to be life threatening. The first case of VBD in maxillofacial region was reported by Romer in 1924, Handbuch der speziellen pathologischen Anatomie and histology, Springer, Berlin. Since then, there have been few case reports of the same in maxillofacial region. We present a review of cases of VBD in maxillofacial region reported in literature along with our experience of a case.

Keywords: Gorham’s disease, Massive osteolysis, Lymphatic proliferation, Haemangiomatosis, Bone resorption

Introduction

“Vanishing bone disease”, as the name suggests, is a condition in which any bone starts vanishing or disappearing. The word “vanishing” has been used with respect to the disease’s radiographic presentation. It is an extremely rare disease with around two hundred cases reported so far. About 30 % of these cases have been reported in maxillofacial region. It has been addressed by various authors as per their observations and nature of the disease by different names viz. Vanishing bone disease, Gorham’s disease, phantom bone disease, acute essential bone resorption, spontaneous or progressive or idiopathic osteolysis, hemangiomatosis and lymphangiomatosis.

Credit of the first report of this condition goes to Jackson who observed gradual ‘vanishing’ of humerus of a young male patient following fracture [1]. He reported the case as “A boneless arm” in 1838 and again published his perspective on the same condition in 1872. He speculated that this was one of the complications of traumatic insult to the bone. There was a latent period of about half a decade before Romer reported the first case of a bone disappearing in maxillofacial region in a middle aged woman [2]. Its first detailed description was given by Gorham in 1954 and Gorham and Stout in 1955 [3, 4]. Since then few authors have reported the occurrence of this disease in different bones of human skeleton. Because of the rarity of the disease, there is no case series from a single author/institution or established line of treatment for the same. Reviews of case reports published in literature have guided us in understanding the demographic, clinical, radiographic and management aspects of the disease.

The disease can be seen in any age group but is mostly prevalent in young adults. There is no gender or racial predilection. Genetic predisposition is not thought to play a role. Presenting complaints may include pain, swelling or inflammation of overlying soft tissue. Patients have also presented with pathologic fracture of the involved bone with revelation of the disease on radiologic investigation. The disease is mainly monostotic but polyostotic/multicentric cases have also been reported. Most commonly involved bones are pelvis, humerus and mandible [5–7].

Various theories have been put forth to explain pathogenesis of the disease. These include abnormal proliferation of vascular tissue; activation of silent hamartoma by minor trauma; hydrolysis by enzymes due to local hypoxia and acidosis; stimulation of osteoclasts due to increased sensitivity of osteoclastic precursors to humoral factors promoting osteoclast formation and bone resorption; proliferation of lymphatic endothelium with rise in circulating PDGF BB; and disordered vascular malformations [8–15].

In initial stages, the bone is rapidly replaced by vascular connective tissue and may be associated with pain and swelling of variable intensity. Microscopic picture is that of proliferation of thin walled vessels (capillary, sinusoidal, or cavernous). In late stages, there is aggressive osteolysis with replacement of involved bone by fibrous tissue [15, 16]. Course of disease is unpredictable and severity and complications depend upon the bone/bones involved. No line of treatment has had complete consensus but if left untreated, the disease progresses to destroy the involved bone completely. Patients with involvement of thoracic cage or c-spine can lose their life to the disease and those with effected pelvis, humerus or mandible can be functionally impaired. 16 % of the cases are fatal. The figure may be high as long term follow-up of all reported cases has not been taken into consideration. It is generally believed that if the disease process stops with rendered treatment or on its own, the prognosis is good. Recurrence of disease is unpredictable and has even happened with radical resection of the diseased bone and reconstruction with free flap [5–7].

In this article we aim at sharing our experience in the form of a case and analyzing the case reports of Gorhams disease affecting jaws with respect to presenting complaint, demographic data available, signs and symptoms and management with follow-up of the patient.

Our Experience

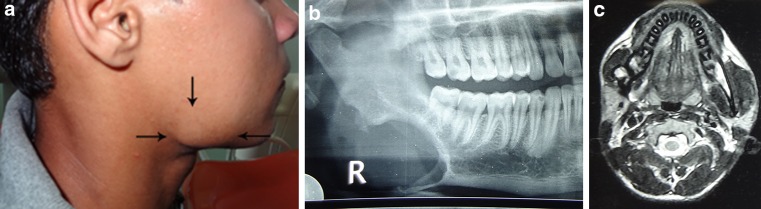

An 18 year old male patient reported to us with recurrent dull pain and gradually increasing swelling in right mandibular angle region since 6 months. There was no other associated symptom except few episodes of low grade fever. On examination there was an extraoral swelling of 3 cm × 2 cm over right angle region. The swelling was soft in consistency but appeared to be submasseteric as masseter could be palpated over swelling on clenching. Earlobe was non-everted and no salivary gland abnormality was noticed. Right submandibular nodes were palpable but non-tender. Intraoral findings were normal. Orthopantomogram revealed a non-sclerotic, well defined radiolucency at angle of the mandible which was more of roundish shape (Fig. 1a). Systemic examination, past medical history and family history were non contributory. Aspiration of the lesion was negative. Hematologic investigations including thyroid profile were all in normal range. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed. It revealed well defined, round to oval area of altered signal intensity which appeared hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2 window at posterior aspect of angle of mandible (Fig. 1b). Incisional biopsy was done intraorally but was inconclusive with remarks stating “Fibrovascular connective tissue with hemosiderin pigment deposit, the sample may not have been from representative site”. Ultrasound guided trucut biopsy was done to no advantage and similar findings were observed under microscope. We were not sure of the character of the lesion but concluded that it was benign and patient was posted for excisional biopsy under general anesthesia. The mass was tumorous, non-encapsulated, merging into adjacent tissues, neither firm nor soft with greenish-brown colour located under the masseter and occupied uniformly resorbed mandibular defect (Fig. 2a, b). The resorption pattern of the bone did not give an impression of resorption by an extrinsic mass (which usually exhibits saucerised resorption pattern). The mass was firmly attached to the resorbed bone as well as it had created a tunnel between buccal and lingual cortices in the surrounding bone giving an impression of intra-bony centrifugal resorption (Fig. 2a). Histological examination revealed dense fibrous collagenous tissue with few dilated capillaries and heavy deposition of hemosiderin pigment (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 1.

a Preoperative presentation of swelling at right angle of the mandible. b Preoperative OPG of the patient showing bone loss at angular region of the mandible. Pointed bone ends can be appreciated around foci of bone loss. c T2 weighed MRI image showing enhancement of the lesion

Fig. 2.

a Intra-operative view of the surgical site after removal of the lesion. b Excised specimen

Fig. 3.

a Photomicrograph showing poorly cellular fibrous tissue with dilated thin walled vessels and large number of macrophages filled with hemosiderin pigment. H&E ×100. b Higher magnification of the same field H&E ×400

There was an array of possible anomalies which could be considered before formulating the final diagnosis. Endocrinal and infectious etiology was ruled out by hematologic investigations. Cystic, salivary and metastatic etiology was completely ruled out by the histological picture. Clinical, operative and histological presentation pointed towards a benign intra-bony growth of fibrovascular nature. Systemic examination of the patient was normal which indicated towards a localized disease. All these findings ruled out idiopathic multicentric osteolysis (with its systemic variants) and aggressive fibromatosis. The clinical, radiological and histological findings were correlated to formulate the final diagnosis of “Gorham’s disease”. Patient was kept under follow-up for 6 months.

Serial orthopantomograms were done to confirm dormancy of disease. Patient was also symptom free. The patient however, complained of a depression at mandibular angle region. After 8 months, reconstruction of mandibular angle defect was done using porous polyethylene (Medpore® implant) (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

a Intra-operative view showing reconstruction of angular region by Medpore® blocks. b Post-operative OPG of the patient showing presence of screws. Medpore® is not visible due to its radiolucent property

Review of Maxillofacial Cases

The first maxillofacial case of VBD was reported by Romer in 1924 [2]. Patient was a middle aged woman with involvement of mandible. The report was non-interventional (observational) without microscopic findings [2]. Thoma in 1933 reported a similar multicentric process in maxillofacial region of a middle aged woman involving both the jaws, palate and sphenoid bone. He reported the lesion to comprise of connective tissues and capillaries [17]. This case report was also observational and no intervention was done to target cure. Knolle and Meyer were the first to attempt treatment of maxillofacial VBD by instituting osteogenic substrates in the form of calcium, phosphate and vitamin D along with radiation to halt the disease process [18]. Phillips in 1972 attempted medical treatment of the disease with steroids, fluoride and calcium. The reason behind use of steroids was presence of chronic inflammatory cells in his microscopic analysis [19]. Booth in 1974 was the first to attempt bone grafting and metal implant for pathologic fracture secondary to VBD [20]. Murphy in 1978 used bone graft along with supportive therapy with calcium and vitamin D to treat multicentric VBD [21]. Heuch was first to use radiation as a cure for mandibular VBD [22]. He was followed by Heffez et al. [23] who opted for radiation to control multicentric VBD of facial bones. Hirayama introduced the use of bisphosphonates to arrest bone resorption and switch bone turn over to positive side [14]. Kawasaki in 2003 used combination of low dose radiation and surgery to treat multicentric VBD involving vertebra in addition to facial bones [24]. Lee in 2003 reported a case with 12 years of follow up treated with combination of radiotherapy, chemotherapy and surgery but patient was lost to chylothorax eventually [25]. Escande et al. in 2006 used interferon alpha with a proposition for it to be anti-angiogenic and lack side-effects of bisphosphonates [26].

In total 51 cases of maxillofacial VBD have been reported before our report [2, 7, 14–61]. Age ranged from 4 months to 72 years with slight male predilection. Presenting complaint of the patient is also variable. Some patients report with acute onset of pain while others report with chronic dull pain in the affected jaw. Pain may be mild to moderate in intensity and may or may not be radiating in nature. Swelling is not rare. Overlying skin is usually normal. Personal and family histories are generally irrelevant. Forty-two out of 51 cases have been microscopically tested. In most of the cases microscopic findings are of a fibrous connective tissue with moderate to rich vascularity along with chronic inflammatory cells. The microscopic findings are mentioned in Table 1. No treatment was rendered in 13 cases. Radiation was opted as treatment modality in 12 patients but was used as sole treatment modality in 7 patients. In the other 5 patients, it was used in combination with pharmacological or surgical measures. Surgical resection/curettage with or without bone grafting has been used in 22 cases. Out of these 22 cases, 14 cases have deployed surgical measures as sole treatment modality. Other 8 cases have witnessed a combination of surgery with radiation or pharmacological measures or both.

Table 1.

Review of maxillofacial cases of VBD reported till date

| S. No. | References | A/S | Site | Microscopic findings | Intervention | Yrs/Srv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Romer [2] | 31/F | Uni-Mn | – | Obv | – |

| 2 | Thoma [17] | 36/F | Mlt-Mn, Mx, Pa, Sph | Connective tissue and capillaries | Obv | 10/N |

| 3 | Steenhuis and Nauta [26] | 45/F | Mlt-Mn, Mx | Inflammatory cells | Obv | 1/N |

| 4 | Pasnikowski and Grec [27] | 47/M | Uni-Mn | Hemangiomatosis | Obv | 5/Y |

| 5 | Knolle and Meyer [18] | 22/M | Uni-Mn | Hemangiomatosis | Phm + Rad-(Ca, Ph, Vit-D) | 7/Y |

| 6 | Hampton and Arthur [28] | 14/F | Mlt-Mn, Mx, CrBs | Fibrovascular tissue | Obv | 16/N |

| 7 | Ellis and Adams [29] | 72/F | Mlt- Mn, Mx, Pa, Sph | Hemangio-endothelial tissue | Obv | 6/N |

| 8 | El Mofty [16] | 55/F | Uni-Mn | Decrease in trebaculations, fibrous tissue, absence of osteoclasts | Obv | –/Y |

| 9 | Cherrick et al. [30] | 27/M | Mlt-Mn, Mx | Chronic inflammatory cells, fibrosis | Obv | –/Y |

| 10 | Malter [31] | 30/M | Mlt-Mn, Mx | Osteolysis | Obv | –/Y |

| 11 | Phillips et al. [19] | 20/M | Uni-Mn | Chronic inflammatory cells, vascular and granulation tissue | Phm-(Str + Ca + Flr) | 7/Y |

| 12 | Kriens [32] | 69/F | Mlt-Mn, Mx, Zyg, Ptr | Chronic inflammation, Granulation tissue with bone sequestration | Obv?? | 16/Y |

| 13 | Black et al. [33] | 27/M | Mlt-Mn, Mx | Osteoclasts | Phm-(Vit D) | 4/Y |

| 14 | Booth and Bruke [20] | 29/M | Uni-Mn | Connective tissue rich in vascularity | Surg-(Bone grafting) | –/Y |

| 15 | Cadenat et al. [34] | 8/M | Uni-Mn | Fibrous and inflammatory tissue | Obv | 8/Y |

| 16 | Murphy et al. [21] | 34/M | Mlt-Mn Mx, Zyg, Sph, Fr | Hemaniomaous Granulation tissue | Phm + Surg-(Bone grafting Ca, Vit D) | |

| 17 | Heuck [22] | 22/M | Uni-Mn | Loose connective tissue rich in vascularity | Rad | 7/Y |

| 18 | Frederiksen et al. [35] | 66/F | Mlt-Mn Zyg arch | Residual trebaculae filled with vascular fibrous tissue | Surg-(Bone grafting) | 5/Y |

| 19 | Heffez et al. [62] | 13/M | Mlt-Mn Mx, Zyg arch, Ptr | Fibrovascular tissue | Rad | 3/Y |

| 20 | Mathias et al. [36] | 16/F | Uni-Mn | Angiomatous tissue | Rad | 6/Y |

| 21 | Takeda et al. [37] | 46/F | Uni-Mn | Fibrous tissue, thin walled vessels | Surg | –/Y |

| 22 | Anavi et al. [38] | 24/F | Uni-Mn | Fibrous connective tissue, thin walled vessels | Surg-(resection and recon) | –/Y |

| 23 | Fisher and Pogrel [39] | 57/M | Uni-Mn | Intramedullary fibrosis | Surg-(Bone grafting) | –/Y |

| 24 | Ohya et al. [40] | 46/F | Uni-Mn | Connective tissue | Surg-(Resection and recon) | 4/Y |

| 25 | Ohya et al. [40] | 66/M | Mlt-Mn, Mx | Connective tissue | Surg-(Resection and recon) | –/Y |

| 26 | Freedy and Bell [41] | 31/M | Uni-TMJ | Thin walled vessels | Surg- | 0.75/Y |

| 27 | Ohnishi et al. [42] | 42/M | Uni-Mn | Intramedullary granulation tissue | Surg- | 6/Y |

| 28 | Kayada et al. [43] | 64/M | Uni-Mn | – | Obv | –/Y |

| 29 | Moore et al. [44] | 21/F | Mlt-Mn, Mx, Orb | – | Surg-Resection and bone grafting | ? |

| 30 | Diaz Ramon et al. [45] | 51/M | Uni-Mx | Decrease trebaculation and fibrous tissue | Rad | ? |

| 31 | Klein et al. [46] | 44/M | Mlt-Mn, Mx, Zyg, Orb | Fibrous tissue replacing bone marrow | Obv | –/Y |

| 32 | Bouloux [47] | 19/F | Uni-Mn | Chronic inflammatory cells | Phm (sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, phenoxymethyl penicillin) | –/Y |

| 33 | Holroyd et al. [48] | 4/M | Uni-Mn | Abnormal thin walled vessels | Phm-Etoposide | 2/N |

| 34 | Oujilal et al. [49] | 17/M | Mlt-TMJ, Orb | Bone trbaculae, endothelial cells | Rad | 3/Y |

| 35 | Hirayama et al. [14] | 7/F | Uni-Mn | – | Surg + Phm-(Bisphos, Resection) | 5/Y |

| 36 | Plontke et al. [50] | 54/F | Mlt-Temp, Occ, Atl | Angiomatous lesion | Rad | 0.66/Y |

| 37 | Kawasaki et al. [24] | 29/F | Mlt-Mn, Occ, Temp, Vert | Edematous bone marrow with osteolysis | Surg + Rad | 15/N |

| 38 | Lee et al. [25] | 4 m/F | Mlt-Zyg, Par, Mn, Vert | Fibroconnective tissue, thin walled anastamosed vessels | Surg | 6/N |

| 39 | Lee et al. [25] | AB/F | Uni-Mn | Fibroconnective tissue, thin walled anastamosed vessels | Surg + Rad + Phm | 12/N |

| 40 | Ricalde et al. [51] | 5/M | Uni-Mn | Thin walled vascular spaces | Rad + Surg-Recon | –/Y |

| 41 | Paley et al. [52] | 55/F | Uni-Mn | Connective tissue, No necrosis | Phm + Surg-Bisphos | –/Y |

| 42 | Escande et al. [53] | 36/M | Uni-Mn | Blood vessel proliferation, Fibrosis, Bone resorption | Surg, Bisphos, alpha Interpheron | –/Y |

| 43 | Moizan et al. [54] | 35/M | Uni-Mn | Chronic inflammatory changes | Surg-Recon Free fibula | 1.5/Y |

| 44 | Zhong et al. [55] | 31/M | Mlt-Mn, Mx, Zyg arch | Chronic inflammation | Surg-recon with medpore | 0.83/Y |

| 45 | Gondivkar and Gadbail [7] | 58/M | Uni-Mn | Fibrous tissue, chronic imflammatory cells, vascular proliferation | Surg-Resection | –/Y |

| 46 | Tong et al. [56] | 9/F | Uni-Mn | – | Phm + Surg-Bisphos, Free fibula | 13/Y |

| 47 | Sharma et al. [57] | 32/M | Uni-Mn | – | – | –/Y |

| 48 | Perschbacher et al. [58] | 56/M | Uni-Mx | Fibrous connective tissue, chronic inflammatory cells, vascular proliferation, osteolysis | Rad + Phm-Bisphos | 4/Y |

| 49 | Huang et al. [59] | 32/M | Uni-Mn | Peripheral soft tissue: Hyperplasia of vessels, degeneration of muscle fibres, | Surg | 0.5/Y |

| 50 | Reddy and Jatti [60] | 38/M | Uni-Mn | – | Phm-Ca, Vit D | 9/Y |

| 51 | Al-Jamali et al. [61] | 33/F | Mlt-Mn, Mx | Fibrovascular tissue with chronic inflammatory cells | Rad | –/Y |

| 52 | Our case | 18/M | Uni-Mn | Dense collagenous fibrous tissue, dilated capillaries, heavy presence of extracellular hemosiderin pigment. | Surg-Currettage, secondary recon | 2.5/Y |

A Age, Atl Atlas, Bisphos Bisphosphonates, Ca Calcium, CrBs Cranial base, F Female, Flr Fluoride, Fr Frontal, M Male, Mn Mandible, Mlt Multicentric, Mx Maxilla, Obv Observational, Occ Occipital, Orb Orbital, Pa Palate, Phm Pharmacological, Ph Phosphorus, Ptr Pterygoid, Rad Radiation, Recon Reconstruction, S Sex, Sph Sphenoid, Srv Survival, Str Steroids, Surg Surgery, Temp Temporal, Uni Unicentric, Vit-D Vitamin D, Vert Vertebrae, Yrs Follow-up in Years, Zyg Zygomatic, – Not reported

Discussion

Hardegger et al. classified idiopathic osteolytic lesions into five types based on their clinical features. Gorham’s massive osteolysis (VBD) is represented in the classification as Type IV idiopathic osteolysis. Description of VBD in the classification says “Monocentric occurrence in any part of the skeleton may start at any age. Normally hemangiomatous tissue is found in the osteolytic region. It has neither a hereditary pattern nor an associated nephropathy. The disease is benign and the osteolysis usually stops after a few years” [62].

There are no characteristic signs and symptoms or radiographic presentation or histological picture for VBD. Its diagnosis is more of an exclusion of other disease processes along with few common details which have been noticed in prior reports. Haffez et al. compiled these two facts and gave the following diagnostic criteria for VBD: (1) A positive biopsy, (2) the absence of cellular atypia, (3) minimal or no osteoblastic response and absence of dystrophic calcification, (4) evidence of local, progressive osseous resorption, (5) non-expansile, non-ulcerative lesion, (6) absence of visceral involvement, (7) osteolytic radiographic pattern, (8) negative hereditary, metabolic, neoplastic, immunologic, or infectious aetiology [63]. Common underlying causes of osteolysis are infection, cancer, and inflammatory or endocrine disorders. The diagnosis of Gorham–Stout syndrome should be suspected or made only after excluding these aforementioned conditions. Aneurysmal bone cyst, distant metastasis from lungs or breast, and osteosarcoma may resemble with VBD in the radiographic picture but can be differentiated with histopathology [6]. Aggressive fibromatosis is a condition which may closely resemble VBD. However, it generally affects soft tissues (fascia and muscles) and the most common site for occurrence is abdomen. Rare extra-abdominal locations reported in head and neck region are parotid gland, tonsillar fossa and pharynx. It may involve bone secondarily but it is primarily a soft tissue pathology. Our case meets all eight diagnostic criteria established by Hafeez et al. Clinical features, history taking, radiographic investigation and microscopic picture were all in sync with reported findings and thus it led us to think in the direction of VBD.

Etiopathogenesis of the disease is still cloudy. Multiple theories have been proposed but none has been able to explain the disease process completely. Following are the few main theories:

Endothelial cells: Gorham and Stout were first to propose that osteolysis is caused by proliferation of endothelial lined channels which influence local environment by changing its pH and/or by applying direct mechanical force and/or consistent increase in blood flow. The other explanation for bone loss is decrease in blood flow to affected area resulting in creation of local acidic milieu which in turn promotes activity of hydrolytic enzymes. Recent literature has piled up enough evidence to state that these endothelial lined vessels are lymphatic in nature. However, the reason behind this lymphangiogenesis is still not clear.

Osteoclasts: The role of osteoclasts has been under investigation since a long time. A lot of investigators have found presence of osteoclasts in histopathological analysis of the excisional specimen. On the other hand, a significant number of investigators have failed to demonstrate presence of osteoclasts in the lesion. One of the explanations given for this is evaluation of lesion at different stages of the lesion (active versus dormant). It has also been suggested that the osteoclasts/osteoclasts progenitor cells of the patients are more sensitive to osteoclasts inducing factors.

Osteoblasts: Osteoblastic activity is generally seen to be increased in the periphery of osteolytic zone. However, in patients with VBD, this compensatory mechanism of bone turnover has not been observed at the region of interest. Also, the same mechanism seems to operate at its norm in other parts of bony skeleton. The explanation of localised suppression of osteoblastic activity is still under investigation.

With regards to diagnostic work-up, radiographic aids in form of plain radiographs, radioisotope bone scans, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have been utilized. Initial radiographic findings may infer patchy bone loss as seen in osteoporosis. Later stages exhibit partial to complete dissolution of the cortical structure leading to pointed ends on either side of ‘vanishing foci’. This dissolution may extend beyond the immediate joint to involve adjacent bone [64]. Bone scans show areas of decreased uptake signifying partial or complete absence of bone in advanced lesions. Computed tomography shows areas of uniformly resorbed bone and defect filled by soft tissue of fibrovascular density. However, these findings are variable. Magnetic resonance imaging has been inconsistent with presentation. T1 weighed images usually shows low signal intensity in areas of affected bone, however, T2 weighed images may exhibit moderate to high signal intensity. Administration of contrast leads to enhancement of the lesion [64, 65]. Pre-operative orthopantomogram clearly shows pointed bony ends being formed due to centrifugal resorption at mandibular angle (Fig. 1b). MRI findings in our case have been in accordance with the literature. The lesion appeared hypointense on T1 and enhancement was seen on T2 weighed images.

Histological picture of the disease has not seen much variation, as clearly seen from the reported microscopic findings in Table 1. The histopathological picture in this disease is not diagnostic but informative, and this information when correlated with clinical and radiological findings leads to formation of “most probable diagnosis”. The most common presentation of the disease can be described as hyperplastic connective tissue of fibrovascular nature. Some authors have also described it as neoplastic proliferation of angiomatous tissue. In cases where bone was analysed, the microscopic picture has been a little more variable, probably depending on course of the disease. It has ranged from decrease in trebaculations, chronic inflammatory osteolysis or even sequestration resembling osteomyelitis. Chronic inflammatory cells have also been almost a consistent finding [5–7]. The final microscopic presentation in our case was in complete accordance with the literature. Additional hemosiderin pigmentation may have resulted from the two incisional biopsies done.

The use of biomarkers is under investigation. If one could identify the currently unpredictable course of disease, it would help in planning treatment more effectively. Growth factor VEGF-A (Vascular endothelial growth factor-A) and cytokine IL-6 (Interleukin-6) have been studied. These biomarkers have been observed to be elevated during active phase of the disease and their levels fall with dormancy or treatment rendered. At the same time, this correlation has not been found to be consistent in all patients [15, 66]. Other biomarkers are also under investigation. In our case, the diagnosis of the disease was made after surgical intervention, so we could not think on lines of monitoring biomarkers.

Once the diagnostic work-up tapers to the point of Gorham’s disease, the main challenge is to figure out the best possible management of this condition. Since the disease was recognised as a separate entity, multiple modalities of treatment have been tried. None of these modalities were used with scientific evidence behind them. Till date, there is no trial or even a case series to support the use of any of these treatment options. However, analysis of multiple case reports has given us a vague insight into the response of VBD to these treatment modalities. However, since the disease has been reported to have predilection for spontaneous arrest, a confident projection of any treatment modality as “Cure” would be inappropriate.

Amongst pharmacological means, multiple agents have been tried ranging from simple osteogenic nutrients (Calcium, phosphorus, Vitamin D) to hormonal therapy with calcitonin. Steroids have been instituted due to consistent finding of chronic inflammatory cells. Anti-osteoclastic agents in form of bisphosphonates have been tried to arrest the bone resorption. Interferon alpha-2b, like other agents, also failed to elicit predictable outcome.

Surgery and radiation have been the two mainstay of treatment. Surgery is more feasible in cases of localized disease and operable region. Radiation therapy has been advocated more for inoperable areas or multifocal disease process or in case of recurrence after surgical resection/curettage with or without reconstruction. Dosage for definitive radiation therapy is in moderate range i.e. 40–45 Gy in 2 Gy fractions. It has also been advocated to be used in low dose as adjunctive modality during active phase of disease process with the purpose of arresting osteolysis before surgical intervention is planned [67, 68]. However, radiation therapy is not deprived of its side effects which include osteonecrosis of the facial bones, malignant transformation, radiation-induced maldevelopment (especially in children), hyperpigmentation (which can be of concern especially in maxillofacial region), soft tissue constriction/atrophy (extremely unaesthetic) and so on.

The extent of surgical intervention completely depends upon the spread and location of disease process. If a bone is completely involved with osteolysis, it may require resection. However, if the disease process is localized to a small region, marginal resection or curettage may be sufficient. Response to surgical intervention has not been predictable but it is acceptable taking into consideration the response to other modalities of treatment. As far as the consensus on primary reconstruction of the defect is concerned, the general opinion is against it. Reconstruction of the defect should be delayed until dormancy of osteolysis is confirmed. This is due to a simple fact that extension of disease or recurrence of disease has happened into the grafted segments [51]. On the other hand a case was reported where free fibula was placed to replace mandibular defect and rehabilitation with dental implants was also done successfully [55]. The location of diseased portion of mandible was favourable in our case. Usually the foci of lesion is believed to be in cancellous part of mandibular body which then gradually spreads to involve basal bone and ascending rami. In such a scenario, the goal of reconstruction is not only aesthetics, but also functional. In our case, the focus seems to be at the anatomical angle of mandible, which is a very rare site for occurrence of not only VBD but also for any other pathology. This localised osteolysis prevented loss of continuity of the mandible. Reconstruction was not done primarily but patient’s persistent complaint of depression at the angle of mandible pushed us for the same after 8 months of observation. However, we were reluctant to use autogenous bone graft as we were intimidated by possibility of osteolysis of grafted segment. Hence, we opted for reconstruction with Medpore as the principal reason for reconstruction was only aesthetics, which could be easily achieved by defining the angular region with implantation of Medpore blocks.

Conclusion

Our knowledge of the Vanishing bone disease has increased enormously with respect to clinical, radiographic and microscopic presentation since its first report. However, the arenas for understanding the true etiology and deciding or predicting the management outcome are still wide open. Thus, an in-depth understanding of VBD and its management requires trials with global recruitment of the patients.

One such initiative has been the launch of lymphangiomatosis and Gorham’s Disease Alliance global patient Registry (www.LGDARegistry.org). It may help to gather patients for clinical trials.

References

- 1.Jackson JBS. A boneless arm. Boston Med Surg J. 1838;18:368–369. doi: 10.1056/NEJM183807110182305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romer O. Die pathologie der zahne. In: von Henke F, Lubarsch O, editors. Handbuch der speziellen pathologischen Anatomie and histology. Berlin: Springer; 1924. pp. 135–499. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorham LW, Wright AW, Schultz HH, Maxon FC. Disappearing bones. A rare form of massive osteolysis: report of two cases, one with autopsy findings. Am J Med. 1954;17:674–682. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone). Its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37:985–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel DV. Gorham’s disease or massive osteolysis. Clin Med Res. 2005;3:65–74. doi: 10.3121/cmr.3.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiran DN, Anupama A. Vanishing bone disease: a review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gondivkar SM, Gadbail AR. Gorham–Stout syndrome: a rare clinical entity and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:e41–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knoch H-G. Die Gorhamsche Krankheit aus klinischer Sicht. Zentralbl Chir. 1963;18:674–683. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickson GR, Hamilton A, Hayes D, Carr KE, Davis R, Mollan RA. An investigation of vanishing bone disease. Bone. 1990;11:205–210. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90215-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson JS, Schurman DJ. Massive osteolysis: case report and review of literature. Clin Orthop. 1974;103:206–211. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197409000-00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young JW, Galbraith M, Cunningham J, Roof BS, Vujic I, Gobien RP, et al. Progressive vertebral collapse in diffuse angiomatosis. Metab Bone Dis Relat Res. 1983;5:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0221-8747(83)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heyden G, Kindblom L-G, Nielsen JM. Disappearing bone disease: a clinical and histological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moller G, Priemel M, Amling M, Werner M, Kuhlmey AS, Delling G. The Gorham Stout symdrome (Gorham Massive Osteolysis): a report of six cases with histopathological findings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:501–506. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B3.9468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirayama T, Sabokbar A, Itonaga I, et al. Cellular and humoral mechanisms of osteoclast formation and bone resorption in Gorham–Stout disease. J Pathol. 2001;195:624–630. doi: 10.1002/path.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devlin RD, Bone HG, III, Roodman GD. Interleukin-6: a potential mediator of the massive osteolysis in patients with Gorham-Stout disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1893–1897. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.5.8626854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Mofty S. Atrophy of the mandible (massive osteolysis) Oral Surg. 1971;31:690–700. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(71)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thoma KH. A case of progressive atrophy of the facial bones with complete atrophy of the mandible. J Bone Joint Surg. 1933;15:450–494. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knolle G, Meyer D. Massive osteolysis in the mandibular region caused by hemangiomatosis of the bone. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kieferheilkd Zentralbl Gesamte. 1965;45:433–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips RM, Bush OB, Jr, Hall HD. Massive osteolysis (phantom bone, disappearing bone), report of a case with mandibular involvement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;34:886–896. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Booth DF, Burke CH. Massive osteolysis of the mandible: an attempt at reconstruction. J Oral Surg. 1974;32:787–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy JB, Doku HC, Carter BL. Massive osteolysis: phantom bone disease. J Oral Surg. 1978;36:318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heuck F. Case report 78. Skeletal Radiol. 1979;3:241–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00360944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heffez L, Doku HC, Carter BL, Feeney JE. Perspectives on massive osteolysis. Report of a case and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:331–343. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawasaki K, Ito T, Tsuchiya T, Takahashi H. Is angiomatosis an intrinsic pathohistological feature of massive osteolysis? Report of an autopsy case and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:400–406. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0765-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S, Finn L, Sze RW, Perkins JA, Sie KC. Gorham Stout syndrome (disappearing bone disease): two additional case reports and a review of literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1340–1343. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.12.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steenhuis DJ, Nauta JH. Osteolyse der ganzen mandibular durch chronische entzundung. Rontgen Praxis. 1936;8:607–609. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasnikowski T, Grec S. Mandibular atrophy (Gorham’s Disease) case report. Pol Tyg Lek. 1960;15:1277–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hampton J, Arthur JF. Massive osteolysis affecting the mandible. Br Dent J. 1966;120:538–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis DJ, Adams TO. Massive osteolysis: report of a case. J Oral Surg. 1971;29:659–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cherrick HM, King OH, Jr, Dorsey JN., Jr Massive osteolysis (disappearing bone, phantom bone, acute absorption of bone) of the mandible and maxilla. J Oral Med. 1972;27:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malter IJ. Massive osteolysis of the mandible: report of a case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1972;85:148–150. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1972.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kriens O. Progressive maxillofacial osteolysis: a case report. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1973;2:73–80. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.1973.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black MJ, Cassisi NJ, Biller HF. Massive mandibular osteolysis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;100:314–316. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1974.00780040324016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cadenat H, Bonnefont J, Barthelemy R, Fabie M, Combelles R. The phantom mandible. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1976;77:877–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frederiksen NL, Welsey RK, Sciubba JJ, Helfrick J. Massive osteolysis of the maxillofacial skeleton: a clinical, radiographic, histologic and ultrastructural study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:331–343. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathias K, Hoffmann J, Martin K. Gorham–Stout syndrome of the mandible. Radiologe. 1986;26:439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeda Y, Kuroda M, Suzuki A, Fujioka Y, Takayama K. Massive osteolysis of the mandible. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1987;37:677–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1987.tb00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anavi Y, Sabes WR, Mintz S. Gorham’s disease affecting the maxillofacial skeleton. Head Neck. 1989;11:550–557. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880110614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher KL, Pogrel MA. Gorham’s syndrome (massive osteolysis): a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1222–1225. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90543-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohya T, Shibata S, Takeda Y. Massive osteolysis of the maxillofacial bones: report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:698–703. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90003-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freedy RM, Bell KA. Massive osteolysis (Gorham’s disease) of the temporomandibular joint. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992;101:1018–1020. doi: 10.1177/000348949210101210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohnishi T, Kano Y, Nakazawa M, Sakuda M. Massive osteolysis of the mandible: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:932–934. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kayada Y, Yoshiga K, Takada K, Tanimoto K. Massive osteolysis of the mandible with subsequent obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:1463–1465. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore MH, Lam LK, Ho CM. Massive craniofacial osteolysis. J Craniofac Surg. 1995;6:332–336. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diaz-Ramon C, Fernandez-Latorre F, Revert-Ventura A, Mas-Estelles F, Domenech-Iglesias A. Idiopathic progressive osteolysis of craniofacial bones. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25:294–297. doi: 10.1007/s002560050083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klien M, Metelmann HR, Gross U. Massive osteolysis (Gorham Stout Syndrome) in the maxillofacial region: an unusual manifestation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25:376–378. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(06)80035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bouloux GF, Walker DM, McKellar G (1999) Massive osteolysis of the mandible report of a case with multifocal bone loss. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 87:357–361 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Holroyd I, Dillon M, Roberts GJ. Gorham’s Disease: a case(including dental presentation) of vanishing bone disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:125–129. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(00)80027-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oujilal A, Lazrak A, Benhalima H, Boulaich M, Amarti A, Saidi A, et al. Massive lytic osteodystrophy or Gorham–Stout disease of the craniomaxillofacial area. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol. 2000;121:255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plontke S, Koitschev A, Ernemann U, Pressler H, Zimmerman R, Plasswilm L. Massive Gorham–Stout osteolysis of the temporal bone and the carniocervical transition. HNO. 2002;50:354–357. doi: 10.1007/s001060100561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ricalde P, Ord RA, Sun CC. Vanishing bone disease in a five year old: report of a case and review of literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:222–226. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paley MD, Lloyd CJ, Penfold CN. Total mandibular reconstruction for massive osteolysis of the mandible (Gorham–Stout syndrome) Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:166–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Escande C, Schouman T, Francoise G, Haroche J, Menard P, Piette JC, Bertrand JC, Ruhin-Poncet B. Histological features and management of a mandibular Gorham disease: a case report and review of maxillofacial cases in the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:e30–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moizan H, Talbi M, Devauchelle B. Massive mandibular osteolysis: a case report with noncontributive histology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:772–776. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhong LP, Zheng JW, Zhang WL, Zhang SY, Zhu HG, Ye WM, Wang YA, Zhang ZY. Multicentric Gorham’s disease in the oral and maxillofacial region: report of a case and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1073–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.06.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tong ACK, Leung TM, Cheung PT. Management of massive osteolysis of the mandible: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:238–241. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma A, Iyer N, Mittal A, Das D, Sharma S. Vanishing mandible. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:513–516. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perschbacher SE, Perschbacher KA, Pharoah MJ, Bradley G, Lee L, Yu E. Gorham’s disease of the maxilla: a case report. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010;39:119–123. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/52099930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang Y, Wang L, Wen Y, Zhang Q, Li L. Progressively bilateral resorption of the mandible. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:e174–e177. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reddy SJ, Jatti DS. Gorham’s disease: a report of a case with mandibular involvement in a 10-year follow up study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012;41:520–524. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/93696387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Al-Jamali J, Glaum R, Kassem A, Voss PJ, Schmelzeisen R, Schon R. Gorham Stout syndrome of the facial bones: a review of pathogenesis and treatment modalities and report of a case with a rare cutaneous manifestations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2012;114:e23–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hardegger F, Simpson LA, Segmueller G. The syndrome of idiopathic osteolysis: classification, review and case report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67:89–93. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B1.3968152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heffez L, Doku HC, Carter BL, Freeney JE. Perspectives on massive osteolysis: report of a case and review of literature. Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:331–343. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Resnick D. Osteolysis and chondrolysis. In: Resnick D, editor. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 4920–4944. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoo SY, Hong SW, Chung HW, Choi JA, Kim CJ, Kang HS. MRI of Gorham’s disease: findings in two cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2002;31:301–306. doi: 10.1007/s00256-002-0487-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brodzki N, Lansberg JK, Dictor M, Gyllstedt E, Ewers SB, et al. A novel treatment approach for paediatric Gorham–Stout syndrome with chylothorax. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:1448–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dunbar SF, Rosenberg A, Mankin H, Rosenthal D, Suit HD. Gorham’s massive osteolysis: the role of radiation therapy and a review of literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;26:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90968-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fontanesi J. Radiation therapy in the treatment of Gorham’s disease. J Padiatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:816–817. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200310000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]