Abstract

Purpose

To determine the rate of complications and occurrence of pterygoid plate fractures comparing two techniques of Le Fort I osteotomy i.e., Classic Pterygomaxillary Dysjunction technique and Trimble technique and to know whether the dimensions of pterygomaxillary junction [determined preoperatively by computed tomography (CT) scan] have any influence on pterygomaxillary separation achieved during surgery.

Materials and methods

The study group consisted of eight South Indian patients with maxillary excess. A total of 16 sides were examined by CT. Preoperative CT was analyzed for all the patients. The thickness and width of the pterygomaxillary junction and the distance of the greater palatine canal from the pterygomaxillary junction was noted. Pterygomaxillary dysjunction was achieved by two techniques, the classic pterygomaxillary dysjunction technique (Group I) and Trimble technique (Group II). Patients were selected randomly and equally for both the techniques. Dysjunction was analyzed by postoperative CT.

Results

The average thickness of the pterygomaxillary junction on 16 sides was 4.5 ± 1.2 mm. Untoward pterygoid plate fractures occurred in Group I in 3 sides out of 8. In Trimble technique (Group II), no pterygoid plate fractures were noted. The average width of the pterygomaxillary junction was 7.8 ± 1.5 mm, distance of the greater palatine canal from pterygomaxillary junction was 7.4 ± 1.6 mm and the length of fusion of pterygomaxillary junction was 8.0 ± 1.9 mm.

Discussion

The Le Fort I osteotomy has become a standard procedure for correcting various dentofacial deformities. In an attempt to make Le Fort I osteotomy safer and avoid the problems associated with sectioning with an osteotome between the maxillary tuberosity and the pterygoid plates, Trimble suggested sectioning across the posterior aspect of the maxillary tuberosity itself. In our study, comparison between the classic pterygomaxillary dysjunction technique and the Trimble technique was made by using postoperative CT scan. It was found that unfavorable pterygoid plate fractures occurred only in dysjunction group and not in Trimble technique group. Preoperative CT scan assessment was done for all the patients to determine the dimension of the pterygomaxillary region. Preoperative CT scan proved to be helpful in not only determining the dimensions of the pterygomaxillary region but we also found out that thickness of the pterygomaxillary junction was an important parameter which may influence the separation at the pterygomaxillary region.

Conclusion

No untoward fractures of the pterygoid plates were seen in Trimble technique (Group II) which makes it a safer technique than classic dysjunction technique. It was noted that pterygoid plate fractures occurred in patients in whom the thickness of the pterygomaxillary junction was <3.6 mm (preoperatively). Therefore, preoperative evaluation is important, on the basis of which we can decide upon the technique to be selected for safer and acceptable separation of pterygomaxillary region.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12663-014-0720-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Preoperative CT assessment, Pterygomaxillary junction, Pterygoid plate fractures

Introduction

Le Fort I osteotomy has become a standard procedure for the correction of various dentofacial deformities. The junction where the tuberosity of the maxilla and the anterior part of the pterygoid plates meet is referred to as pterygomaxillary junction. During Le Fort I osteotomy, we may not achieve the exact separation of this junction [1]. Anatomical variations in this region such as abnormally thick posterior wall of the maxilla or bony defects can lead to unfavorable pterygomaxillary dysjunction [2]. An unfavourable pterygomaxillary separation could lead to fractures that extend to the pterygomaxillary region, the base of the skull [3], and to the orbit, leading to cranial nerve injuries [4–7], carotid–cavernous sinus fistulas, stroke [8, 9], blindness [10, 11], and even death. In our study, we achieved pterygomaxillary separation by both classic pterygomaxillary dysjunction technique described by Bell [12] and modified vertical cut technique described by Trimble et al. [13]. The purpose of the study was to compare the two techniques and to know whether the dimensions of pterygomaxillary junction (determined preoperatively by CT scan) have any influence on pterygomaxillary separation achieved during surgery.

Materials and Methods

Patients

8 South Indian patients (5 female and 3 male) with age range of 20–30 years with maxillary excess were selected to undergo Le Fort I osteotomy. Patients were assigned to the classic pterygomaxillary dysjunction group (I) or Trimble technique (tuberosity technique) group (II) in random fashion consisting of four patients in each group respectively. A total of 16 sides were evaluated (eight sides in each group). Informed consent was obtained by all patients and the protocol was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board.

Surgical Technique

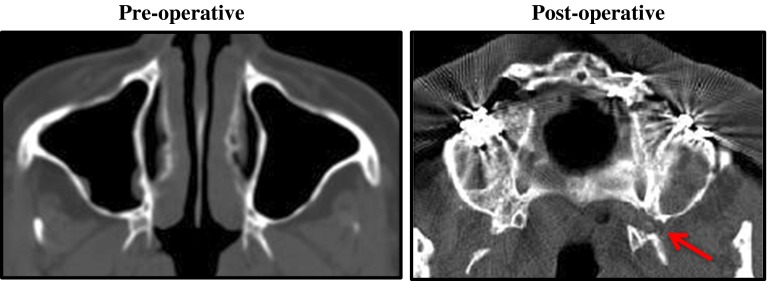

Four patients (Group I) underwent classic pterygomaxillary dysjunction technique in which separation occurs between posterior wall of the maxilla and the pterygoid plates as described by Bell for the classic technique group. The lateral wall of the maxilla was osteotomized with a 702 bur and the lateral nasal wall was osteotomized with a lateral nasal osteotome. The cartilaginous septum and vomer were separated with a nasal septum osteotome, and the curved pterygoid osteotome was used to separate the maxilla from the pterygoid plates. Preoperative and post-operative CT images of one of the patients operated by this technique has been shown for better understanding of the cut in the pterygomaxillary region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative and postoperative CT image of a patient operated by classic pterygomaxillary dysjunction technique. Arrow denotes the cut at the pterygomaxillary junction

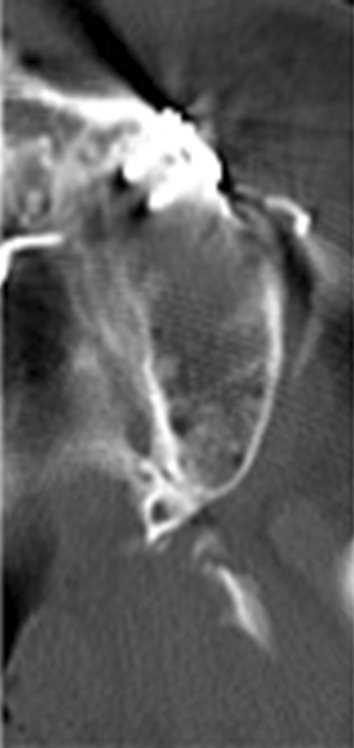

The other four patients (Group II) underwent Trimble technique in which a vertical cut is made on the tuberosity in the third molar region avoiding the pterygomaxillary junction. In this technique, after osteotomizing the lateral wall of the maxilla and lateral wall of the nose, and separating the cartilaginous septum and vomer, pterygomaxillary separation was achieved by making the cut in the tuberosity region distal to the second molar. Firm digital pressure in the area of the premaxilla was applied in an inferior direction in order to downfracture the maxilla. If the applied force did not result in downfracturing of the maxilla, the osteotomies were re-examined to ensure that they were complete. Pre-operative and post operative images of one patient are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative and postoperative CT images of a patient treated with Trimble technique. Arrow denotes the cut at the tuberosity

CT Scan Assessment

The patients were placed in the gantry with the tragacanthal line perpendicular to the ground for CT scanning. CT scans were obtained using a high speed, advantage-type CT generator with each sequence taken 1.25 mm apart for the 3D reconstruction. Posterior nasal spine level was selected to measure the pterygomaxillary region. Radiant Dicom Viewer Imaging Software was used for morphologic measurements.

Measurements Using CT

The parameters used for assessing preoperative CT scan were (Fig. 3):

Thickness of the pterygomaxillary junction (T): posterior wall of the maxillary sinus to the pterygoid fossa (Fig. 4).

Width of pterygomaxillary junction (W): most concave point on the lateral surface of the pterygomaxillary junction (C) to the most medial point of the pterygomaxillary fissure (Fig. 5).

G: distance from the greater palatine foramen to the C (Fig. 6).

F: length of line of fusion between pterygoid plate and tuberosity measured from base of pterygoid plate to the lowest point in sphenopalatine fossa (Fig. 7)

Fig. 3.

Diagrammatic representation of the parameters assessed by preoperative CT

Fig. 4.

Preoperative CT depicting thickness (T)

Fig. 5.

Preoperative CT depicting width (W)

Fig. 6.

Preoperative CT depicting distance of the pterygomaxillary junction from the greater palatine canal (G)

Fig. 7.

Preoperative CT depicting length of line of fusion between pterygoid plate and tuberosity (F)

Postoperative CT scans were observed for occurrence of pterygoid fractures or any other complications such as evidence of untoward fractures extending to the pterygopalatine fossa, the orbit, or the base of the skull.

Results

The dimensions of the pterygomaxillary junction were recorded in all 8 patients (Groups I and II). The mean thickness (Table 1) of pterygomaxillary region was 4.5 ± 1.2 mm. The average width (Table 2) of the junction was 7.8 ± 1.5 mm, the average distance of the greater palatine foramen from the maximum concavity(C) of the pterygomaxillary junction was 7.4 ± 1.6 mm (Table 3) and the average length of fusion between pterygoid plates and tuberosity was 8.0 ± 1.9 mm (Table 4).

Table 1.

Thickness (T) of pterygomaxillary junction in all 8 patients (16 sides)

| Patients | Classic dysjunction group (Group I) | Patient | Trimble technique group (Group II) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (mm) | L (mm) | R (mm) | L (mm) | ||

| Patient 1 | 3.6 | 4.6 | Patient 5 | 6.0 | 6.5 |

| Patient 2 | 4.2 | 4.1 | Patient 6 | 4.6 | 5.4 |

| Patient 3 | 3.3 | 3.5 | Patient 7 | 4.2 | 5.2 |

| Patient 4 | 3.0 | 2.8 | Patient 8 | 4.6 | 6.8 |

Average Thickness (T) of 16 sides = 4.5 mm ± 1.2 mm

Bold values represent the sides in which pterygoid plate fractures occurred

Table 2.

Width (W) of pterygomaxillary junction in all 8 patients (16 sides)

| Patients | Classic dysjunction group (I) | Patient | Trimble technique group (II) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (mm) | L (mm) | R (mm) | L (mm) | ||

| Patient 1 | 6.0 | 5.6 | Patient 5 | 9.3 | 9.3 |

| Patient 2 | 10.9 | 9.8 | Patient 6 | 7.0 | 7.1 |

| Patient 3 | 8.5 | 6.9 | Patient 7 | 6.8 | 8.8 |

| Patient 4 | 9.2 | 6.8 | Patient 8 | 6.6 | 6.8 |

Average width (W) of 16 sides = 7.8 ± 1.5 mm

Table 3.

Distance of greater palatine canal (G) from pterygomaxillary junction in all eight patients

| Patients | Classic dysjunction group (I) | Patients | Trimble technique group (II) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (mm) | L (mm) | R (mm) | L (mm) | ||

| Patient 1 | 6.5 | 5.5 | Patient 5 | 6.5 | 7.2 |

| Patient 2 | 10.8 | 9.4 | Patient 6 | 7.9 | 7.6 |

| Patient 3 | 7.5 | 5.2 | Patient 7 | 6.0 | 7.9 |

| Patient 4 | 9.6 | 8.4 | Patient 8 | 5.5 | 6.8 |

Average distance G = 7.4 ± 1.6 mm

Table 4.

Length of line of fusion between pterygoid plate and tuberosity (F) in all eight patients

| Patients | Classic dysjunction group (I) | Patients | Trimble technique group (II) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (mm) | L (mm) | R (mm) | L (mm) | ||

| Patient 1 | 8.7 | 7.2 | Patient 5 | 5.0 | 6.1 |

| Patient 2 | 7.4 | 6.0 | Patient 6 | 6.7 | 4.7 |

| Patient 3 | 9.5 | 10.0 | Patient 7 | 10.0 | 10.1 |

| Patient 4 | 9.5 | 9.2 | Patient 8 | 9.9 | 7.7 |

Average length of fusion (F) = 8.0 ± 1.9 mm

Although postoperatively, acceptable separation between the maxilla and the pterygoid plates was achieved and the maxillary segments could be moved to the postoperative ideal position in all 8 cases (16 sides), low level pterygoid plate fractures occurred (Table 1, Fig. 9) in 3 sides out of 8 in Group I. Fracture occurred in patients in whom thickness of the pterygomaxillary junction was less than or equal to 3.6 mm. In Group II, postoperative CT showed no pterygoid plate fractures. No other major complications such as skull base fractures were seen in postoperative CT scan in either of the two groups.

Fig. 9.

Postoperative CT showing left side lateral pterygoid plate fracture

Discussion

Several complications associated with Le Fort I osteotomy, such as hemorrhage from sphenopalatine, descending palatine and maxillary arteries [6, 9], arteriovenous fistulae [14, 15], skull base fracture [16], cranial nerve injury [4, 7, 10, 15], blindness [10, 11], ophthalmic complications [17] and internal carotid artery injury [3], have all been reported in the literature. Many of these complications have been attributed to the non-ideal separation of the pterygomaxillary junction. It has been implicated that unfavorable separation between the pterygoid plates and the posterior maxillary walls may result in horizontal or oblique fractures of the pterygoid plates that can be the prime cause of the above mentioned complications [18, 19]. However, it has been noticed that pterygoid plate fractures can occur independent of any other complications. These independent pterygoid plate fractures can also be a problem because the fractured segments interfere with the mobilization of the maxilla during advancement or setback [13].

In our study, we used classic pterygomaxillary dysjunction technique [12] (Group I) and Trimble technique [13] (Group II) to achieve pterygomaxillary separation. With postoperative CT scan assessment, it was found that unfavorable pterygoid plate fractures occurred only in dysjunction group and not in Trimble technique group which means that the latter technique is safer as far as pterygoid plate fractures are concerned. In a study of the alternative approaches to the pterygomaxillary separation carried out in fresh cadavers by Lanigan and Guest [20] it was found that the conventional technique resulted in ideal separations in only 3/20 sides (15 %), low-level fractures in 12/20 sides (60 %), and high-level fractures in 5/20 sides (25 %). The “Trimble” technique resulted in ideal separations in 9/20 sides (45 %), low-level separations in 6/20 sides (30 %), and high-level fractures in 5/20 sides (25 %). While the “Trimble” technique therefore led to an improvement in the incidence of ideal separations, it still led to a high incidence of high-level pterygoid plate fractures. This is the only other study that has directly compared the conventional technique to the “Trimble” technique. In view of this study (twenty sides), and the small sample size in our current study (eight sides), it is an overstatement to assume that a favourable separation will always occur when using the “Trimble” technique. It is still a reasonable conclusion to draw, however, based on these two studies, that the “Trimble” approach is a better technique than the conventional technique from the standpoint of improving the incidence of ideal separations and decreasing the overall incidence of pterygoid plate fractures. Even clinically, Trimble technique provides several advantages over the more classically described technique. The major advantage is the technical ease because of better access and visibility as compared to the cut through the pterygomaxillary junction where proper placement and angulation of the osteotome is often difficult due to poor access and visibility. Mobilization of the maxilla is more easily achieved as fewer muscles remain attached to the maxilla, whereas in pterygomaxillary dysjunction technique, due to non-ideal separation, part of the pterygoid plate remains attached to the tuberosity as well as fibers of lateral and medial pterygoid muscles and tensor veli palatini. These muscle attachments inhibit anterior movement of the maxilla and are difficult to release. Even setback becomes difficult due to bony interferences present posteriorly. Additionally, these unfavorable fractures do not allow stabilizing bone grafts to be placed between the pterygoid plates and the posterior maxilla when the maxilla or a segment is moved forward. These complications are not likely to occur when the osteotomy is completed through the tuberosity [13]. Both setback and advancement is easily achieved by Trimble technique. All these clinical advantages combined with postoperative CT scan findings showing absence of pterygoid plate fractures further justifies that Trimble or modified vertical cut technique is a much safer procedure to achieve separation in the pterygomaxillary region than the classic pterygomaxillary dysjunction technique in cases of Le Fort I osteotomy. Rennick and Symington [19] in their study also indicate that pterygomaxillary dysjunction using the classic technique is often complicated by fractures of the pterygoid plates.

Anatomical variations of the pterygomaxillary region are one of the reasons for pterygoid plate fractures or non-ideal separation of this region [2]. Therefore, preoperative CT scan assessment was done for all the patients to determine the dimension of the pterygomaxillary region. Preoperative CT scan proved to be helpful in not only determining the dimensions of the pterygomaxillary region but we also found out that thickness of the pterygomaxillary junction is an important parameter which may influence the separation at the pterygomaxillary region. Thicker the junction, less chances of pterygoid plate fractures. This finding has been supported by other studies too. Hwang et al. [21] reported in an experimental study of Le Fort I osteotomy using an osteotome in Korean dry skulls that the thickness of the pterygomaxillary region was significantly greater in the dysjunction group than in the fracture group. The mean thickness of the pterygomaxillary region was 7.70 mm in the dysjunction group and 4.70 mm in the fracture group. In our study the mean thickness of pterygomaxillary region was 4.5 mm (Table 1). Results of our study were similar to Hwang study because pterygoid plate fractures were present in those patients in whom thickness was <3.6 mm. These variations in values of different studies can be probably due to ethnic differences. Average width of the junction is 7.8 mm (Table 2), average length of fusion between pterygoid plates or tuberosity is 8.0 ± 1.9 mm (Table 4) and the mean position of greater palatine canal from the junction was 7.4 mm (Table 3). All these findings coincide with the separate studies done by Hwang et al. [21] and Cheung et al. [22]. Length of fusion between pterygoid plates and tuberosity or the length of pterygomaxillary junction is also a very important anatomical feature. Studies have shown that untoward fractures generally occur in patients having a longer junction. According to Cheung et al. [22], the mean height of pterygomaxillary junction was 12.07 but it could be as short as 8.94 mm. Average height was 8.0 ± 1.9 mm in our study. Again, differences in values can be due to ethnicity. More the height more the risk of pterygoid plate fractures but our study did not show any correlation with this finding. Most of the studies related to pterygomaxillary region are either done on dry skulls [21, 22] or done on Korean or Japanese population [1, 23, 24]. In our study, we have made an attempt to determine the dimensions of pterygomaxillary region in South Indian population.

It is implicated (Fig. 8) that when pterygomaxillary junction is thin, the force from the osteotome is dissipated into a larger area and hence horizontal or oblique fractures travel through the pterygoid plate. However, when the junction is thick, force from the osteotome is absorbed by the thick junction and hence ideal or near ideal separation is achieved. Hence thin pterygomaxillary regions are vulnerable to fracture of pterygoid plates [18]. In case of thin junction, we can perform a vertical cut through the tuberosity or Trimble technique. This will avoid untoward fractures of pterygoid plates (Fig. 9) and further complications. Hence, preoperative computed tomography review is greatly helpful before surgery as we can opt for a safer technique (Trimble technique) knowing the dimensions of pterygomaxillary region (especially thickness) and thereby reducing the risk of complications specially in cases such as craniofacial malformations [24], including cleft lip and palate [2], and patients with previous midfacial trauma or previous maxillary orthognathic surgery.

Fig. 8.

Preoperative CT scan showing thick and thin pterygomaxillary junction

It is worth mentioning that, thickness should not be considered the only criteria for unfavorable pterygoid plate fractures. Occurrence of pterygoid plate fractures has been frequently attributed to improper use of instruments such as incorrect angulation of the osteotome or use of a blunt osteotome [22]. If the cutting edge of the osteotome is large and thick, it tends to cause blunt, shattering injury rather than a sharp cut through the junction of the maxillary tuberosity and the pterygoid plates [20]. Therefore, various designs of osteotomes such as swan neck osteotome [25, 26] and shark-fin osteotome [27] have been used for a safer and more controlled separation of pterygomaxillary junction. Use of a micro-oscillating saw [28] if available has shown best results to achieve pterygomaxillary separation. Factors like improper angulation of the osteotome, blunt chisel, forceful downfracturing of the maxilla, poor access and visibility and surgeon’s experience are the other factors responsible for unfavorable pterygoid plate fractures. Additionally, male gender along with increased age can be significant risk factors for unfavorable pterygoid plate fractures [29]. Most of our patients were below 25 years of age, and we had only 3 male patients, therefore, it is difficult to correlate factors like increased age and male gender with our present study.

Conclusion

Trimble Technique can be considered as a safer technique for Le Fort I osteotomy as pterygoid plate fractures did not occur with this technique. Even clinically, Trimble Technique provides better access and visibility and avoids important structures in pterygomaxillary region.

Thickness of the junction proved to be an essential parameter as pterygoid plate fractures occurred in patients in whom pterygomaxillary junction was significantly thin. The identification of this predictive factor may permit the preferential selection of a specific technique for mobilization of the maxilla in a given individual, thus reducing the occurrence of pterygoid plate fractures and other complications. Therefore, preoperative CT scan assessment can be considered an important tool in identifying any anatomical variations in the pterygomaxillary region which may influence the separation later on. Hence, it will be useful if all patients are assessed preoperatively with the help of CT scan. It is noteworthy that factors like blunt chisel, incorrect angulation of the chisel, limited access and visibility and surgeon’s experience can also cause pterygoid plate fractures. Hence, thickness should not be considered as the only predisposing factor for pterygoid plate fractures.

No major complications occurred. Repositioning of the maxilla was achieved in all cases. This further implicates that pterygoid plate fractures may occur independent of any other complications and there may not be any direct causal relationship between pterygoid plate fractures and major complications.

It is not always possible to achieve an ideal separation but acceptable separation was achieved and maxilla was moved to its ideal position in all cases. The morphology and the variations in the pterygomaxillary region, combined with the surgical reality that access is limited and that pterygomaxillary separation is a blind procedure, may explain why non-ideal separation and pterygoid plate fractures are a common occurrence. Shortcomings of our study is the small sample size, hence a large sample size is required to establish strong correlation with the present study.

Electronic supplementary material

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standard

Ethical approval was given by the Institutional Ethical Committee, SRM Dental College, Ramapuram, Chennai-89. Reference Number: SRMU/M&HS/SRMDC/2010-1013/M.D.S-PG Student/403. Patient consent: Written patient consent has been obtained to publish clinical photographs.

References

- 1.Ueki K, Hashiba Y, et al. Assessment of pterygomaxillary separation in Le Fort I osteotomy in class III patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee Seung-Hun, et al. Evaluation of pterygomaxillary anatomy using computed tomography: are there any structural variations in cleft patients? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2644–2649. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang SY, et al. Importance of complete pterygomaxillary separation in the Le Fort I osteotomy: an anatomic report. Skull Base. 2009;19(4):273–277. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr RJ, Gilbert P. Isolated third nerve palsy following Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy in a patient with cleft lip and palate. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:206. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newlands C, Dixon A, Altman K. Ocular palsy following Le Fort 1 osteotomy: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:101–104. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JW, et al. Cranial nerve injury after Le Fort I osteotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiner S, Willoughby JH. Transient abducent nerve palsy following a Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:699. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Politis C, et al. Life-threatening hemorrhage after 750 Le Fort I osteotomies and 376 SARPE procedures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:702–708. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newhouse RF, Sehow SR, et al. Life threatening hemorrhage from a Le Fort I osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982;40:117. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(82)80039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz AAV. Blindness after Le Fort I osteotomy: a possible complication associated with pterygomaxillary separation. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006;34(4):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lun-Jou et al (2002) Blindness as a complication of Le Fort I osteotomy for maxillary distraction. J Plast Reconstr Surg 109:688 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Bell WH. Le Fort I osteotomy for correction of maxillary deformities. J Oral Surg. 1975;33:412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trimble LD, Tideman H, Stoelinga PJW. A modification of the pterygoid plate separation in low level maxillary osteotomies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:544. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goffinet L, et al. An arteriovenous fistula of the maxillary artery as a complication of Le Fort I osteotomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2010;38:251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith et al (2008) Traumatic arteriovenous malformation following Le Fort I osteotomy. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 45(3):329–332 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Bhaskaran AA, et al. A complication of Le Fort I osteotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:292–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanigan DT, Romanchuk K, Olson CK. Ophthalmic complications associated with orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:480. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Precious DS, Goodday RH, et al. Pterygoid plate facture in Le Fort I osteotomy with and without pterygoid chisel: a computed tomography scan evaluation of 58 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:515. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rennick BM, Symington JM. Postoperative computed tomography study of pterygomaxillary separation during the Le Fort I osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:1061. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90139-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanigan DT, Guest P. Alternative approaches to pterygomaxillary separation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;22:136. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80236-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang K et al (2001) Le Fort I osteotomy with sparing fracture of lateral pterygoid plate. J Craniofac Surg 12(1):48–53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Cheung LK, et al. Posterior maxillary anatomy: implications for Le Fort I osteotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;27:346–351. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(98)80062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueki Koichiro, et al. Assessment of bone healing after Le Fort I osteotomy with 3-dimensional computed tomography. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueki Koichiro, et al. Determining the anatomy of the descending palatine artery and pterygoid plates with computed tomography in Class III patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37:469–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wikkeling OME, Tacoma J. Osteotomy of the pterygomaxillary junction. Int J Oral Surg. 1975;4:99. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(75)80001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng LHH, Robinson PP (1993) Evaluation of a swan’s neck osteotome for pterygomaxillary dysjunction in the Le Fort I osteotomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 31:52–53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Laster Z, Ardekian L, Rachmiel A, et al. Use of the ‘shark-fin’ osteotome in separation of the pterygomaxillary junction in Le Fort I osteotomy: a clinical and computerized tomography study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:100–103. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juniper RP, Stajcic Z. Pterygoid plate separation using an oscillating saw in Le Fort 1 osteotomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991;19:153. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(05)80304-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanazawa T, Kuroyanagi N, Miyachi H, et al. Factors predictive of pterygoid process fractures after pterygomaxillary separation without using an osteotome in Le Fort I osteotomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115(310):310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.