Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate the difference between the combination agent of xylitol, beatine and olive oil in a chewable capsule versus the control agent of a sorbitol tablet in subjects with hyposalivation and xerostomia.

Materials and Methods

The subjects had xerostomia over 3 months and a measured hyposalivation. The study was 3 weeks in duration, with 2 treatment phases of 1 week and a 7 day wash out period in between. At the end of each treatment phase, subjects returned for a follow up evaluation. At this visit they were given the subjective sensation questionnaire, as well as their unstimulated whole salivary flow and stimulated whole salivary flow were measured.

Results

There was a greater increase in the unstimulated and stimulated whole salivary flow rate, although the results were not statistically significant. The subjective evaluation as measured by the questionnaire showed that both agents reduced the mean score as compared to the baseline, although only the findings in the active agent was statistically significant (p = 0.0015).

Conclusion

The significant conclusions found in this study were that the active agent provided a significant subjective improvement in speech, swallowing, and decreased subjective xerostomia as compared to the control tablet.

Clinical Relevance

This combination agent has a significant effect on patients with subjective xerostomia but does not have a significant effect on objective hyposalivation.

Keywords: Betaine, Hyposalivation, Xerostomia, Xylitol, Olive Oil, Dry Mouth

Introduction

Salivary gland dysfunction can be caused by a multitude of disease processes. The etiologies generally fall into the following categories: viral and bacterial infections, radiation, autoimmune. This dysfunction can result in hyposalivation and xerostomia.

In the literature hyposalivation and xerostomia are used interchangeably. For the purpose of this publication, the term xerostomia will be in regards to the subjective feeling or a dry mouth, without specifying whether or not there is salivary hyposecretion. The diagnosis of salivary gland hypofunction is based on salivary flow measurements [1–5]. The term hyposalivation is used, when the whole salivary secretion is <0.1–0.2 ml/min at rest and under 0.5 to 0.7 ml/min of stimulated saliva [1]. The symptom of xerostomia can be used as an additional assessment of glandular hypofunction if measured in an objective fashion. This is performed utilizing verified questionnaires [5]. As will be shown in this study, the data on xerostomia and hyposalivation do not always correlate, and like other researches, the data is separated as it would be in two separate, but related disease entities [6–8].

When there is an appreciable decrease in the amount of saliva in the oral cavity, adverse clinical manifestations can occur and generally, there is an overall decrease in the quality of life of the patient. Functionally, there can be impairment in speaking, chewing, swallowing and taste perception [1–5, 9–18]. Dentally, there is a demineralization of the teeth, progressive periodontal disease, and mucositis [1–4, 9–11, 16, 18]. As the disease progresses, other than dry oral mucosa and saliva thickening, there have been reports of mouth burning, pain, depression, irritability and sleep alterations [1, 4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 14–17].

It is difficult to specify what the prevalence of hyposalivation and xerostomia is in the general population because in a majority of cases, the symptoms are nonspecific and painless, the terminology can be inconsistent and presence of diagnostic variability [10]. The published research does provide similar, although not significant, prevalence rates ranging between 20 and 30 %, with a higher incidence in older women and in polymedicated individuals [7, 9–12]. Interestingly, there is some indication that there is an upward trend in younger adults, although the etiology is unknown [12].

Treatment of salivary dysfunction can be challenging. If the etiology can be identified, particularly in polymedicated individuals, an alteration in the medication regimen can be attempted. In cases where there is no such possibility, such as in patients who have received head and neck radiation or in symptomatic Sjögren’s Syndrome, palliative intervention should be attempted. Currently, there exist numerous products that provide relief of the symptoms of xerostomia. The delivery systems of these are: sprays, rinses, pastes, tooth pastes, gum, and candy.

In this study, the active palliative agent was a combination agent of xylitol, beatine and olive oil in a chewable capsule (Xerostom Chewable Relief Capsules® Biocosmetics laboratories, Madrid, Spain) versus the control agent of a non-stimulatory sorbitol chewable tablet. In a prior study, the combination product was shown to have a significant reduction in xerostomia, as well as a stimulatory effect on salivary volume/time, although multiple delivery systems were used [10]. The overall purpose of this study was to compare the combination preparation in a chewable delivery system against a non-stimulatory chewable agent in subjects with hyposalivation and xerostomia.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion Criteria

The subjects had to have symptoms of dry mouth that continued over 3 months duration, a non-stimulated whole salivary secretion of 0.1–0.2 ml/min measured over 5 min and a stimulated whole salivary secretion lower than 0.5 to 0.7 ml/min over 5 min. These flow rates were determined in consensus at the Symposium on Xerostomia and Dry Mouth in 2007 and have been adopted by The Spanish Society of Oral Medicine as the defining flow rate of hyposalivation [3, 15, 19].

Exclusion Criteria

Subjects who had an intrinsic loss of salivary functions were excluded from the study because they lacked the ability to express any saliva, which was one of the aims of this study. These subjects were patients who underwent irradiation of 60 Gy or more in the head and neck region, patients who had a salivary gland removed, and patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.

Patients who did not follow directions or who did not attend follow up appointments were removed from the study and the data was not used. Subjects could discontinue their participation, voluntarily, at any time of the study and without prejudice to future treatments.

The compliance of <60 % of the administered agents during each week of treatment was considered insufficient and subjects would be dismissed from the study for noncompliance.

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the law of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. It also obtained approval from the Clinical Trials Committee of the Hospital Clinico San Carlos in Madrid and was sponsored by a contract under Article 83 of the Organic Law of Universities between Biocosmetics Laboratories® and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

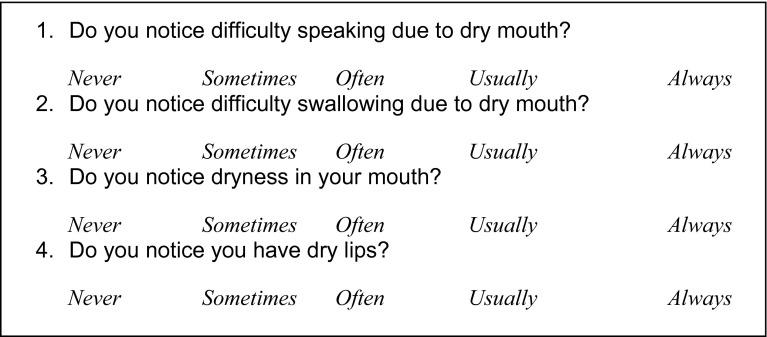

The study was 3 weeks in duration, during which subjects used a saliva stimulant Xerostom® and a sorbitol control tablet. A repeated measures study was done because the 34 subjects were given both the non-stimulant control and the stimulant agent, but differed in the sequence in administration of the control versus the active agent. Subjects maintained their usual medications and oral hygiene routine throughout the study. Each arm of the methods was 7 days long with the second week being a wash out period. At the end of each treatment phase, subjects returned for a follow up evaluation. At this visit they were given the subjective sensation questionnaire (Fig. 1), as well as their unstimulated whole salivary flow and stimulated whole salivary flow were measured. Responses on the questionnaire were scored from 0 to 4: never (0 points), sometimes (1 point), often (2 points), usually always (3 points) and always (4 points).

Fig. 1.

Subjective evaluation of xerostomia

Active Agent

The active agent was a combination product of betaine, olive oil and xylitol (Xerostom®, Madrid, Spain) and the control agent, a sorbitol tablet. Both agents weighed 173 mg. Subjects were instructed to take one tablet at breakfast and at lunch, and two tablets between lunch and dinner, although not at the same time. During the wash out week, subjects were instructed to drink only water for management of symptomatic xerostomia.

Statistical Analysis

The database management and data analysis were performed using SAS version 9.1 program. Since the distribution of the samples was not normal, we had to use nonparametric tests. Tests applied were Wilcoxon signed ranks test and McNemar test. The significance level was set at 5 % (alpha error 0.05, confidence interval 95 %).

Results

One hundred patients were contacted from the database of the Department of Orofacial Medicine and Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Spain), who were being treated for oral dryness. Of these, only 34 met the inclusion criteria and consented to be subjects.

There were 27 (79.4 %) females and seven (20.5 %) males. The mean age of members was 67.79 ± 9.46 years. The mean duration of hyposalivation was 8.31 years.

In the subjects history, 85.29 % of subjects took at least one xerostomic medication daily, 52.92 % of subjects took 2–4 xerostomic medications a day. In addition, 14.7 % had received radiation therapy of <60 Gy for oral carcinomas, 47 % had been diagnosed with burning mouth syndrome, and 23.5 % had psychiatric disorders. In 29.4 % of the subjects, no identifiable etiology could be identified. Removable dentures were present in 50 % of the subjects. All subjects treated their hyposalivation utilizing xylitol containing products.

No subjects withdrew or were withdrawn from the study or deviated from the experimental protocol.

Unstimulated Whole Saliva Flow

The sialometry at visit 1 was 0.12 ± 0.07 ml/min on an average. After taking the control, subjects gained an average of 0.14 ± 0.15 ml/min. After taking the active agent, (Xerostom® saliva substitute), a flow rate of 0.15 ± 0.14 ml/min was measured. Although there was a greater increase in the unstimulated whole salivary flow rate, the difference between control and the active product was not statistically significant (p = 0.88).

Stimulated Whole Saliva Flow

The base line median stimulated whole saliva flow was 0.44 ± 0.23 ml/min. After taking the control, a median flow rate of 0.43 ± 0.28 ml/min was measured. After taking the active agent, a flow rate of 0.46 ± 0.28 was obtained. Once again, the stimulated salivary flow rate was increased versus the control, although not statistically significant (p = 0.53).

Xerostomia Questionnaire

Subjective evaluation as measured by the questionnaire resulted in a mean score of 9.41 ± 4.14 at visit 1. After treatment with the control, the mean score decreased to 8.97 ± 4.14 points, and after treatment with Xerostom® saliva substitute, the average score was 8.15 ± 4.02 points. Both agents reduced the mean score as compared to the baseline, although only the findings in the active agent was statistically significant (p = 0.0015).

Comparison between the Unstimulated/Stimulated Flow Rates and the results of the Xerostomia Questionnaire are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of results

| Cohorts | Unstimulated salivary flow | Stimulated salivary flow | Xerostomia questionnaire |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control versus baseline | No improvement in salivary flow rate | No improvement in salivary flow rate | Non-Significant improvement of score |

| Experimental versus baseline | Non-significant improvement in salivary flow rate | Non-significant improvement in salivary flow rate | Significant improvement in score |

| Experimental versus control | Non-significant improvement in salivary flow rate | Non-significant improvement in salivary flow rate | Significant improvement in score |

Discussion

When designing the methodology of this study, one of the key difficulties was limiting the experimental cohort to subjects with stable and somewhat predictable clinical findings. With this in mind, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were formulated to reduce the amount of variability. The basis of these parameters was obtained in reviewing the current literature. Many studies included subjects that had inherent changeability, like Sjögren’s Syndrome, or patient’s without function of their salivary glands [7, 19–22]. Therefore, it was decided to exclude Sjögren’s Syndrome patients, because of the unpredictable fluctuation of their salivary flow and the intrinsic nature of their disease, and patients who had undergone head and neck radiation over 60 Gy, because of their complete lack of salivary production [10].

Like other publications the present study subjects were predominantly female. The suggested reason for this skewed gender differentiation is based upon the premise that more females are diagnosed because they are more likely than males to visit outpatient clinics when they recognize they have abnormal symptoms [7, 16, 23, 24].

Given the advanced age of the subjects of the present study, it seems logical that more than one-third of them were denture-wearing, as was the case in the study by Davies [7]. In the rest of the studies reviewed it is not indicated whether the patients had removable dentures. Given the difficulty of treating hyposalivation/xerostomia and the many products in the market, it is not surprising that in our study patients had tried numerous agents and procedures without having found an acceptable solution to their condition. Note that, typically, patients use combinations of treatments, not a single product, with 50 % of patients reporting utilization of predominantly lemon flavored and sugar free candies for attempted relief of their xerostomia/hyposalivation.

The combined agent (Xerostom®) is comprised of betaine, olive oil and xylitol. Betaine is an amino acid derivative, obtained from sugar beet molasses during sugar production. Orally, it functions as an osmoprotectant and has been found to decrease chemical irritation and mechanical abrasions [25]. Olive oil has many properties helpful in ameliorating oral conditions commonly found in dry mouth patients including antimicrobial properties, lubrication, anti-inflammatory, and anti-caries activities [26–29]. Xylitol is a sugar alcohol that functions as a salivary stimulant [30, 31]. Although it is difficult to ascertain the exact mechanism that reduced the xermostomic symptoms, the most likely agents were the betaine, which decreases the loss of water from the mucous component of saliva, and the olive oil, which creates a sensation of a frictionless mucosa. Although there was a non-significant improvement in the Xerostomia Questionnaire in the Control Cohort, most likely this increase would be minimized by increasing the control and experimental cohort size.

Of interest, Ship and Godiksen had statistically significant improvement in unstimulated salivary production after the use of Xerostom® for a week and consuming unflavored chewing gum for 2 weeks, respectively [10, 20]. In comparing these two studies with different controls, this small increase in the former study could be explained by the induced salivary secretion from mechanical action of the chewing gum.

There were no statistically significant differences in the sialometry after the use of the active agent (Xerostom®) capsules. The changes in this study were comparable to the Epstein study in which Oralbalance® gel and Biotene® toothpaste were tested [32].

Along with sialometry, the Likert Questionnaire was asked during the four visits. The questions were compiled and adapted from previously published studies [7, 10, 32, 33]. The answers were always the same, measured on a categorical scale [10, 19, 32, 34].

For the subjective evaluation, we reached, in the first visit a mean score of 9.41 with 0 being the absence of pathology and 16 having an extreme pathology. After taking the control an average score of 8.97 was obtained and 8.15 after treatment with the active agent. In this case, the difference between active agent and the control was statistically significant.

Of interest, as has been shown in many studies, is that the objective measurements of stimulated and unstimulated salivary flow and the subjective Xerostomic Indices rarely correlate [19]. The reason that these measurements do not correlate remains unknown. Because of this, xerostomia and hyposalivation can be considered related, but different disease processes. This has been shown in many studies and correlates with the findings in our study as well [4, 35, 36].

Conclusion

The significant conclusions that can be proven from this study are that the Xerostom® agent provided improvement in speech, swallowing, and decreased subjective xerostomia as compared to the control tablet. Once assessed Xerostom® saliva substitute suckable-chewable capsules can be considered as an agent for the treatment of xerostomia. Another significant finding was that Xerostom® increased the stimulatory whole saliva flow as compared to the control. When taken together, the Xerostom® salivary substitute problem does improve the subjective feeling of xerostomia and also, does increase saliva production.

The study was conducted in accordance with the law of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. It also obtained approval from the Clinical Trials Committee of the Hospital Clinico San Carlos in Madrid and was sponsored by a contract under Article 83 of the Organic Law of Universities between Biocosmetics Laboratories® and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. All subjects who were included in the study gave their informed consent to participation and understood all potential risks and benefits of the study.

None of the authors of this manuscript has or had a conflict of interest in relationship to the study performed and there is no financial relationship, corporate or personal, in regards to Biocosmetics Laboratories®.

Contributor Information

R. C. Lapiedra, Email: rcererol@odon.ucm.es

G. E. Gómez, Email: esparza@odon.ucm.es

B. P. Sánchez, Email: begopalsan@gmail.com

A. A. Pereda, Email: ana_antoranz@yahoo.es

M. D. Turner, Email: mturner@chpnet.org

References

- 1.Scully C, Felix DH. Oral medicine—update for the dental practitioner: dry mouth and disorders of salivation. Br Dent J. 2005;199(7):423–427. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guggenheimer J, Moore PA. Xerostomia: etiology, recognition and treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(1):61–69. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silvestre-Donat FJ, Miralles-Jorda L, Martinez-Mihi V. Protocol for the clinical management of dry mouth. Med Oral: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Medicina Oral y de la Academia Iberoamericana de Patologia y Medicina Bucal. 2004;9(4):273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson JC, Grisius M, Massey W. Salivary hypofunction and xerostomia: diagnosis and treatment. Dent clin N Am. 2005;49(2):309–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bascones ATJ, Ship J, Turner M, Mac Veigh I, López-Ibor JM, Albi M, Lanzós E, Aliaga A. Conclusiones del Symposium 2007 de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Oral sobre “Xerostomía. Síndrome de Boca Seca. Boca Ardiente”. Av Odontoestomatol. 2007;23:119–126. doi: 10.4321/S0213-12852007000300002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jen YM, Lin YC, Wang YB, Wu DM. Dramatic and prolonged decrease of whole salivary secretion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with radiotherapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(3):322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson M, Chalmers JM, John Spencer A, Slade GD, Carter KD. A longitudinal study of medication exposure and xerostomia among older people. Gerodontology. 2006;23(4):205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2006.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson WM. Issues in the epidemiological investigation of dry mouth. Gerodontology. 2005;22(2):65–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2005.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassolato SF, Turnbull RS. Xerostomia: clinical aspects and treatment. Gerodontology. 2003;20(2):64–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ship JA, McCutcheon JA, Spivakovsky S, Kerr AR. Safety and effectiveness of topical dry mouth products containing olive oil, betaine, and xylitol in reducing xerostomia for polypharmacy-induced dry mouth. J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34(10):724–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2006.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirodaria S, Kilbourn T, Richardson M. Subjective assessment of a new moisturizing mouth spray for the symptomatic relief of dry mouth. J Clin Dent. 2006;17(2):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Vigna PTA, Naval MA, Adilson A, Reis L. Saliva composition and functions: a comprehensive review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;3:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanehira T, Yamaguchi T, Takehara J, Kashiwazaki H, Abe T, Morita M, Asano K, Fujii Y, Sakamoto W. A pilot study of a simple screening technique for estimation of salivary flow. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(3):389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suh KI, Lee JY, Chung JW, Kim YK, Kho HS. Relationship between salivary flow rate and clinical symptoms and behaviours in patients with dry mouth. J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34(10):739–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2006.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silvestre FJMM, Suñe-Negre JM. Clinical evaluation of a new artificial saliva in spray form for patients with dry mouth. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;1:E8–E11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan HZ-PL, Wolff A. Association between salivary flow rates, oral symptoms and oral mucosal status. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chanani–Wu N, Gorsky M, Mayer P, Bestrom A, Epstein JB, Silverman S. Assessment of the use of sialologues in the clinical management of patients with xerostomia. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:168–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2006.tb01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies A. A comparison of artificial saliva and chewing gum in the management of xerostomia in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2000;14:197–203. doi: 10.1191/026921600672294077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furumoto EKBG, Carter-Hanson C, Barber BF. Subjective and clinical evaluation of oral lubricants in xerostomic patients. Spec Care Dentist. 1998;18:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1998.tb00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godiksen AGS, Teglers PT, Schiodt M, Glenert U. Comparison between new saliva stimulants in patients with dry mouth: a placebo-controlled double-blind crossover study. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:376–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flink HBM, Tegelberg A, Rosenblad A, Lagerlöf F. Prevalence of hyposalivation in relation to general health, body mass index and remaining teeth in different age groups of adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:523–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarkkila LLM, Tiitinen A, Lindqvist C, Meurman JH. Oral symptoms at menopause—the role of hormone replacement therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:276–280. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.117452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frost PMSP, Challacombe SJ, Fernandes-Naglik L, Walter JD, Ide M. Impact of wearing an intra-oral lubricating device on oral health in dry mouth patients. Oral Dis. 2006;12:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahdad SATC, Barclay SC, Steen IN, Preshaw PM. A double-blind, crossover study of Biotene Oralbalance and BioXtra systems as salivary substitutes in patients with post-radiotherapy xerostomia. Eur J Cancer Care. 2005;14:319–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soderling E, Le Bell A, Kirstila V, Tenovuo J. Betaine-containing toothpaste relieves subjective symptoms of dry mouth. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56(2):65–69. doi: 10.1080/00016359850136003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beauchamp GK, Keast RS, Morel D, Lin J, Pika J, Han Q, Lee CH, Smith AB, Breslin PA. Phytochemistry: ibuprofen-like activity in extra-virgin olive oil. Nature. 2005;437(7055):45–46. doi: 10.1038/437045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming HP, Walter WM, Jr, Etchells JL. Antimicrobial properties of oleuropein and products of its hydrolysis from green olives. Appl Microbiol. 1973;26(5):777–782. doi: 10.1128/am.26.5.777-782.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walter WM, Jr, Fleming HP, Etchells JL. Preparation of antimicrobial compounds by hydrolysis of oleuropein from green olives. Appl Microbiol. 1973;26(5):773–776. doi: 10.1128/am.26.5.773-776.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pretty IA, Gallagher MJ, Martin MV, Edgar WM, Higham SM. A study to assess the effects of a new detergent-free, olive oil formulation dentifrice in vitro and in vivo. J Dent. 2003;31(5):327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0300-5712(03)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moritsuka M. Quantitative assessment for stimulated saliva flow rate and buffering capacity in relation to different ages. J Dent. 2006;34(9):716–720. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart CM. Comparison between saliva stimulants and a saliva substitute in patients with xerostomia and hyposalivation. Spec Care Dentist. 1998;18(4):142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1998.tb01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epstein JBES, Stevenson-Moore P. A double-blind crossover trial of Oral Balance gel and Biotene toothpaste versus placebo in patients with xerostomia following radiation therapy. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:132–137. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fox PCAJ, Macynski AA, Wolff A, Kung DS, Valdez IH, Jackson W, Delapenha RA, Shiroky J, Baum BJ. Pilocarpine treatment of salivary gland hypofunction and dry mouth (xerostomia) Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1149–1152. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400060085014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gil-Montoya JAG-LI, González-Moles MA. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of a mouthwash and oral gel containing the antimicrobial proteins lactoperoxidase, lysozyme and lactoferrin in elderly patients with dry mouth–a pilot study. Gerodontology. 2008;25:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2007.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Hashimi I, Khuder S, Haghighat N, Zipp M. Frequency and predictive value of the clinical manifestations in Sjogren’s syndrome. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30(1):1–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu B, Dion MR, Jurasic MM, Gibson G, Jones JA. Xerostomia and salivary hypofunction in vulnerable elders: prevalence and etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114(1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]