Abstract

Objective

Personality traits related to high Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness are consistently associated with obesity. Hormones implicated in appetite and metabolism, such as leptin, may also be related to personality and may contribute to the association between these traits and obesity. The present research examined the association between leptin and Five Factor Model personality traits.

Methods

A total of 5,214 participants (58% female; Mean age = 44.42 years, SD = 15.93, range 18 to 94) from the SardiNIA project completed the Revised NEO Personality Inventory, a comprehensive measure of personality traits, and their blood samples were assayed for leptin.

Results

As expected, lower Conscientiousness was associated with higher circulating levels of leptin (r=−.05, p<.001), even after controlling for body mass index, waist circumference, or inflammatory markers (r=−.05, p<.001). Neuroticism, in contrast, was unrelated to leptin (r=.01, p=.31).

Conclusions

Individuals who are impulsive and lack discipline (low Conscientiousness) may develop leptin resistance, which could be one factor that contributes to obesity, whereas the relation between a proneness to anxiety and depression (high Neuroticism) and obesity may be mediated through other physiological and/or behavioral pathways.

Keywords: Leptin, Personality traits, Appetite, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, Obesity, Impulsivity, Self-discipline, Inflammation, Depression

Leptin is an adipose-derived hormone that plays a significant role in food intake and energy storage by relaying information between peripheral tissue and the central nervous system. When functioning normally, leptin acts as a signal to the brain to stop eating. Higher levels of leptin typically reduce appetite, but the elevated level found in obese individuals is thought to be due to reduced sensitivity to leptin signaling (i.e., leptin resistance). In addition to its association with physiological factors such as obesity and inflammation (1), leptin has been implicated in a number of cognitive and psychological processes. Although leptin may have neuroprotective effects (2), elevated levels have been associated with poor psychological outcomes, including subjective stress (3) and post-traumatic stress disorder (4), although the findings are mixed on the association between leptin and depression (5, 6).

There is reason to suspect that other psychological factors, specifically personality traits, may be related to circulating levels of leptin. Individuals high in Neuroticism and low in Conscientiousness are more prone to being overweight or obese (7-10), are more likely to experience weight fluctuations (10), have higher levels of inflammation (11, 12), and are more vulnerable to depression (13). The present study examines the association between personality and leptin in a large sample of community-dwelling adults. Given their association with obesity, inflammation, and psychological distress, we hypothesized that high Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness would be associated with higher levels of leptin. In addition to the five broad domains, we examine the association with more specific aspects, or facets of personality. We hypothesize that facets that have previously been linked to obesity (higher impulsiveness, higher assertiveness, lower activity, lower order, lower self-discipline, and lower deliberation) will be associated with higher leptin; we present the results for the remaining facets as exploratory analyses. We also examine whether the associations between personality and leptin are independent of body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and inflammatory markers associated with both leptin and personality (interleukin-6 [IL-6], c-reactive protein [CRP], white blood cells [WBC]). Because the association between personality and leptin may depend on age and it may differ between the sexes, we examine whether these associations vary by age and sex. Finally, we hypothesize that the association between personality traits and adiposity will be partially mediated by higher levels of leptin.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from the SardiNIA project, a large multidisciplinary study of the genetic and environmental basis of complex traits and age-related processes, described in detail elsewhere (14). In brief, from November 2001 to May 2004 we recruited 6,162 individuals, about 62% of the population aged 14 to 102 years, from a cluster of four towns in the Lanusei Valley, Sardinia, Italy. Subjects were native born, and at least 95% were known to have all grandparents born in the same province. Of the total SardiNIA sample, 230 participants (3.7%) did not complete the personality questionnaire due to scheduling conflicts, disinterest, or inability to understand items. These participants tended to be older (Mage = 67.70, SD =17.00) with lower levels of education (5th grade or below). An additional 263 participants (4.4%) were judged to have invalid NEOs based on criteria outlined in the NEO-PI-R manual (15). Participants below the age of 18 (n=354; 6.2%) were excluded because of the effect of puberty on leptin levels (16). Finally, 101 participants did not have reliable leptin values (11 participants had missing values and 90 had values below the detection limit). There were no differences in age, sex, education, or personality between those with and without valid leptin values. Thus, valid personality and leptin data were obtained from 5,214 participants (58% female) over the age of 18 (M = 44.42 years, SD = 15.93, range 18 to 94). This research followed APA ethical standards, was approved by the local Institutional Review Board in the United States and in Italy, and all participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Personality

Personality traits were assessed using the Italian version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R), which measures 30 facets, six for each of the five major dimensions of personality (15). The 240 items were answered on a five-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Participants filled out the self-report questionnaire (88%) or chose to have the questionnaire read by a trained psychologist (12%). A variable (test administration) was used as a covariate in the analyses. Raw scores were converted to T-scores (M = 50, SD = 10) using American combined-sex norms (15). Throughout the paper, the letter and number in parentheses immediately following the facet label refer to the broad domain of personality that the facet belongs to and its number within that domain.

Leptin

Blood samples were drawn from subjects in the early morning after an overnight fast and were processed within 24 hours and stored at room temperature until they were assayed. Serum levels of Leptin were assessed using a single purchased lot of Human Serum Adipokine multiplex testing kit -Panel B (Lincoplex kit, Cat. # HADK2-61K-B, beads #22) according to the manufacturer’s instructions after which the plates were examined using a Luminex multiplex instrument (Luminex, Model number 200 IS; Serial No. LX10006265401). The lower detection limit using these kits is > 85.4 pg/ml by the manufacturer. The intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) for in-house leptin testing was established using a panel of six normal human control sera as well as the Human Adipokine Quality Control I and II (Lincoplex LHA-6061) panel utilized during each assay run and the combined replicate data demonstrated CVs between 3.9-10.3% over the range of 234-23,500 pg/ml. Similarly, the intra-assay CVs established by the manufacturer using the Lincoplex Human Adipokine Quality Control I and II were found to be between 1.4-7.9%.

Adiposity

Participants’ weight and height were measured and recorded by a trained staff clinician, as was waist circumference (measured midway between the inferior margin of the last rib and the crest of the ileum, in a horizontal plane). Derived BMI (kg/m2) was categorized into normal weight (BMI < 25; 49%), overweight (BMI = 25-30; 35%) and obese (BMI ≥ 30; 16%).

Inflammatory markers

Serum IL-6 levels were measured by Quantikine High Sensitive Human IL-6 Immunoassay (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), according to manufacturer’s instructions. This method employs solid-phase ELISA techniques and has a detection limit of 0.016-0.110 pg/mL, with mean sensitivity of 0.039 pg/mL. The intra-assay CVs were 6.9% to 7.4% over the range 0.43-5.53 pg/mL.

Serum levels of high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were measured by the high sensitivity Vermont assay (University of Vermont, Burlington), an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay calibrated with WHO Reference Material (17). The lower detection limit of this assay is 0.007 mg/l, with an inter-assay coefficient of variation of 5.14%.

Total WBC count was performed using standard automated procedures (18). Clinical laboratories in Sardinia provided the blood cell counts.

Analysis

To examine the association between personality traits and leptin, we ran partial parametric correlations controlling for age, age squared, sex, education, and test administration. Additional analyses also controlled separately for BMI, waist circumference, and the inflammatory makers (IL-6, CRP, and WBCs). Age and sex were tested as moderators using Aiken and West’s (19) method for testing interactions. Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) and bootstrapping techniques (20) were used to examine the effect of leptin on personality differences across BMI categories and waist circumference, respectively. The significance level was set at p < 0.05, two-tailed. The empirical p values are reported without correction for multiple testing to avoid inflated type 2 errors (21, 22).

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for all study variables. Consistent with our hypothesis, individuals higher in Conscientiousness had lower levels of leptin (Table), but surprisingly, domain-level Neuroticism was unrelated to leptin. At the facet level, as hypothesized, the traits most commonly associated with obesity (10) were also associated with higher leptin: higher Impulsiveness (N5), higher Assertiveness (E3), lower Order (C2), lower Self-Discipline (C5), and lower Deliberation (C6). Higher levels of Feelings (O3), Ideas (O5), Straightforwardness (A2), Dutifulness (C3), and Achievement Striving (C4) were also correlated with leptin. All associations remained significant when controlling for adiposity (the correlations were similar if either BMI or waist circumference was included as a covariate), or the inflammatory markers (IL-6, CRP, and WBCs), except for Straightforwardness (A2) and Order (C2) (Table 2). Results were also virtually identical to Model 2 when both BMI and the inflammatory markers were entered simultaneously as covariates.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Study variables | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years) | 44.42 (15.93) |

| Sex (% Female) | 3029 (58%) |

| Education (years) | 9.09 (4.06) |

| % Verbal test administration | 646 (12%) |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 8.37 (1.09) |

| Personality (T-score) | |

| Neuroticism | 55.05 (9.01) |

| Extraversion | 48.59 (8.70) |

| Openness | 46.21 (10.09) |

| Agreeableness | 47.03 (9.47) |

| Conscientiousness | 49.60 (9.10) |

| Adiposity | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.52 (4.61) |

| Obesity (% obese) | 822 (16%) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 85.03 (12.87) |

| Inflammatory markers | |

| Interlukin-6 (pg/mL) | 3.16 (3.68) |

| hsC-reactive protein (mg/L) | 2.77 (4.91) |

| White blood cells (103/ul) | 6.68 (1.68) |

Note. N=5214 for demographics, leptin, personality, and adiposity. Ns range from 5185 to 5205 for the inflammatory markers. Means (SD) or percentages for all study variables.

Table 2.

Partial Correlations between Personality Traits and Leptin

| Personality | Model |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Neuroticism | .01 | .00 | .01 |

| Extraversion | .02 | .02 | .02 |

| Openness | .03 | .03* | .02 |

| Agreeableness | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 |

| Conscientiousness | −.05*** | −.05*** | −.05*** |

| Facets | |||

| Anxiety (N1) | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 |

| Angry Hostility (N2) | .00 | −.01 | .00 |

| Depression (N3) | .01 | .01 | .00 |

| Self-Consciousness (N4) | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 |

| Impulsivity (N5) | .08*** | .05*** | .07*** |

| Vulnerability (N6) | .01 | .01 | .00 |

| Warmth (E1) | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Gregariousness (E2) | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Assertiveness (E3) | .05*** | .04** | .04** |

| Activity (E4) | −.02 | −.02 | −.02 |

| Excitement-Seeking (E5) | .01 | .01 | .00 |

| Positive Emotions (E6) | .02 | .01 | .01 |

| Fantasy (O1) | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Aesthetics (O2) | −.01 | .00 | −.01 |

| Feelings (O3) | .03* | .04** | .03* |

| Actions (O4) | .02 | .02 | .01 |

| Ideas (O5) | .04** | .03* | .03* |

| Values (O6) | .01 | .02 | .01 |

| Trust (A1) | .00 | .00 | .01 |

| Straightforwardness (A2) | −.03* | −.02 | −.02 |

| Altruism (A3) | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 |

| Compliance (A4) | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Modesty (A5) | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 |

| Tender-Mindedness (A6) | −.02 | −.03 | −.02 |

| Competence (C1) | −.02 | −.01 | −.02 |

| Order (C2) | −.03* | −.01 | −.02 |

| Dutifulness (C3) | −.04** | −.04** | −.04** |

| Achievement Striving (C4) | −.03* | −.04** | −.03* |

| Self-Discipline (C5) | −.06*** | −.05*** | −.05*** |

| Deliberation (C6) | −.04** | −.03* | −.03* |

N = 5,214. Results of partial correlations. Model 1 controls for age, age squared, sex, education, and test administration. Model 2 controls for the demographic factors and body mass index. Model 3 controls for the demographic factors and the inflammatory markers (interleukin-6, c-reactive protein, white blood cells).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p<.001.

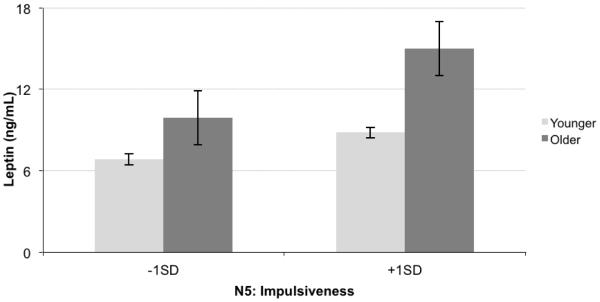

Several of these associations were moderated by age. Older participants who scored higher in Impulsiveness (βN5 × age=.05, p=.001; Figure 1), Assertiveness (βE3 × age=.03, p=.01), factor-level Openness (βO × age=.04, p=.004) and Feelings (βO3 × age=.06, p<.001) had higher levels of leptin, whereas these traits were unrelated to leptin among younger participants. Sex also moderated two of these effects: the association between leptin and Ideas (βO5 × sex=.03, p=.044) held only for men, whereas the association between leptin and Self-Discipline was stronger for women than men (βC5 × sex=.05, p=.005).

Figure 1.

Association between N5: Impulsiveness and leptin plotted separately for older (aged >=50) and younger (aged<50) participants. F(7,5206)=90.99, p <.001.

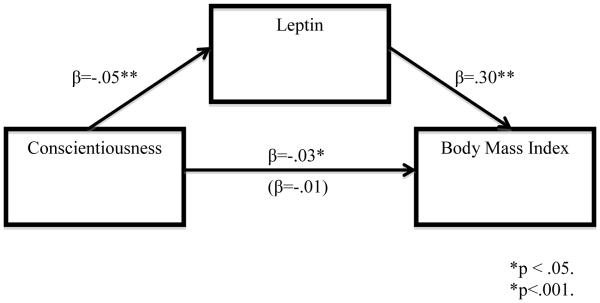

Personality traits in this sample have previously been linked to adiposity (βs range from −.04 to .11) (9). In the present sample, leptin and BMI correlated .31 (p<.001; unadjusted), and most of the associations between the traits and leptin were significant when controlling for BMI or waist circumference, which indicated that BMI/waist circumference did not fully account for the association between personality and leptin. We next tested whether leptin contributed to the relation between personality traits and adiposity. In this sample, BMI was higher participants who scored above the population average (T-score>50) on Neuroticism (low Neuroticism BMI = 25.33 [SE=.10], high Neuroticism BMI = 25.62 [SE=.06], F(1,5204)=5.42, p =.020) and lower than the population average (T-score<50) on Conscientiousness (low Conscientiousness BMI = Conscientiousness = 25.64 [SE=.08], high Conscientiousness BMI = 25.41 [SE=.08], F(1,5204)=4.01, p=.045). Including leptin in the model, however, reduced the differences in BMI across Conscientiousness categories to non-significance (F(1,5203) = 1.08, p=.30), which suggested that leptin may be one mechanism through which low Conscientiousness is related to overweight/obesity. Indeed, leptin mediated the association between Conscientiousness and waist circumference (point estimate = −.0194, 95% CI = −.0287 − −.0116; Δβ = .02) and when BMI was considered as a continuous variable (point estimate = −.0078, 95% CI=−.0114 − − .0042; Δβ = .02; Figure 2). As leptin was not associated with Neuroticism, it did not mediate the association between Neuroticism and obesity, continuous BMI, or waist circumference. Leptin also did not mediate the association between personality and any of the inflammatory markers.

Figure 2.

Model showing that leptin mediates the association between Conscientiousness and body mass index. All coefficients control for age, age squared, sex, education, and test administration.

Discussion

Personality traits are consistently associated with obesity and weight gain in adulthood (7-10). The present study extends research on the association between personality and BMI by examining a possible mechanism for this association. And, indeed, the personality traits that are most consistently related to obesity (10, 23) were also associated with higher levels of leptin. Individuals high in Conscientiousness, particularly the self-discipline aspect of this trait, had lower circulating levels of leptin, whereas those who were impulsive, assertive, and intellectually curious had higher levels of leptin. Several of these associations were stronger at older ages, in particular for the impulsiveness and openness to feelings facets. These two traits are also associated with weight gain across adulthood (10); the association between traits such as impulsiveness and openness with higher levels of leptin may thus be the cumulative result of weight gain with aging. Further, we found support for our hypothesized meditational model: leptin mediated the association between Conscientiousness and adiposity. This effect suggests that leptin is one physiological mechanism that links Conscientiousness to obesity.

Contrary to expectation, Neuroticism was unrelated to leptin. The association between psychological distress and leptin is somewhat controversial. Elevated levels of leptin have been associated with increased risk for major depression in some samples (5), but the opposite has been found in others (6). This discrepancy has led to the hypothesis that there may be a curvilinear relation between leptin and depression, such that both elevated and diminished levels increase risk of depression (6). Our findings do not support this hypothesis: Neuroticism, which measures a general tendency towards depression, did not have either a linear or curvilinear association with leptin (data not shown). Perhaps these associations may be limited to clinical samples with severe depression.

Most of the associations between personality and leptin remained significant after accounting for BMI or waist circumference, which suggests that being overweight or obese did not fully explain the relation between personality traits and leptin. Individuals low in Conscientiousness have greater variability in their weight across adulthood (10) and such weight fluctuations may contribute to dysregulation of leptin over time (24). Thus, there may be an association between Conscientiousness and leptin even when controlling for differences in adiposity because these individuals are more likely to have a history of weight variability.

Low Conscientiousness has also been consistently associated with greater adiposity (7-10) and less aerobic capacity (25). In this study, the meditational analyses indicated that the relation between Conscientiousness and adiposity (obesity, BMI, waist circumference) was reduced by approximately 40%when leptin was included in the model. Conscientiousness measures the tendency to be organized, disciplined, and deliberate. Individuals who score low on this trait tend to procrastinate, lack motivation, and act on impulse. Conscientiousness is generally thought about in social terms, but the inability to follow rules may be part of a broader pattern. In addition to not following external rules, individuals low in Conscientiousness may not follow internal cues either. They may have a physiologically-based insensitivity to signals –internal or external – that reduces their brains’ sensitivity to feelings of satiety. The same was not true for Neuroticism. Because it was unrelated to Neuroticism, leptin could not account for the relation between Neuroticism and obesity as it did for Conscientiousness. Thus, although both Conscientiousness and Neuroticism are associated with obesity, it appears that these associations may be through different physiological and/or behavioral mechanisms.

The present research had several strengths, including a large community sample, a comprehensive measure of personality traits, and control variables (BMI, waist circumference, inflammatory markers) that could have had an effect on the relation between personality and leptin. It is important to note that our sample was from Sardinia, an island known for the Mediterranean diet and lifestyle. Although the prevalence of obesity is relatively low in Sardinia, the genetic (26) and personality (9) correlates of obesity are similar to those in the United States. Future research could test these associations in more urban settings and address the longitudinal and potential bi-directional relation between personality and leptin. In addition, a measure of subcutaneous fat, not just BMI and waist circumference, is needed to more fully examine the relations between personality, leptin, and adiposity. This research is a step toward a better understanding of the physiological factors that contribute to the association between personality and obesity.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging.

Acronyms

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- CRP

c-reactive protein

- WBC

white blood cells

- NEO-PI-R

Revised NEO Personality Inventory

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors has a conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Maachi M, Piéroni L, Bruckert E, Jardel C, Fellahi S, Hainque B, Capeau J, Bastard JP. Systemic low-grade inflammation is related to both circulating and adipose tissue TNFα, leptin and IL-6 levels in obese women. International Journal of Obesity. 2004;28:993–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey J, Shanley LJ, O'Malley D, Irving AJ. Leptin: A potential cognitive enhancer? Biochemical Society Transactions. 2005;33:1029–32. doi: 10.1042/BST20051029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otsuka R, Yatsuya H, Tamakoshi K, Matsushita K, Wada K, Toyoshima H. Perceived psychological stress and serum leptin concentrations in Japanese men. Obesity. 2006;14:1832–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao SC, Lee MB, Lee YJ, Huang TS. Hyperleptinemia in subjects with persistent partial posttraumatic stress disorder after a major earthquake. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:23–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106880.22867.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiménez I, Sobrino T, Rodríguez-Yáñez M, Pouso M, Cristobo I, Sabucedo M, Blanco M, Castellanos M, Leira R, Castillo J. High serum levels of leptin are associated with post-stroke depression. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:1201–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu XY. The leptin hypothesis of depression: a potential link between mood disorders and obesity? Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2007;7:648–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magee CA, Heaven PCL. Big-Five personality factors, obesity and 2-year weight gain in Australian adults. Journal of Research in Personality. 2011;45:332–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roehling MV, Roehling PV, Odland LM. Investigating the validity of stereotypes about overweight employees: The relationship between body weight and normal personality traits. Group and Organization Management. 2008;33:392–424. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terracciano A, Sutin AR, McCrae RR, Deiana B, Ferrucci L, Schlessinger D, Uda M, Costa PT., Jr Facets of personality linked to underweight and overweight. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:682–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a2925b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutin AR, Ferrucci F, Zonderman AB, Terracciano A. Personality and obesity across the adult lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:579–92. doi: 10.1037/a0024286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman BP, van Wijngaarden E, Seplaki CL, Talbot N, Duberstein P, Moynihan J. Openness and conscientiousness predict 34-SSweek patterns of Interleukin-6 in older persons. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2011;25:667–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Deiana B, Naitza S, Ferrucci L, Uda M, Schlessinger D, Costa PTJ. High neuroticism and low conscientiousness are associated with interleukin-6. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1485–93. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendler KS, Myers J. The genetic and environmental relationship between major depression and the five-factor model of personality. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:801–6. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilia G, Chen WM, Scuteri A, Orrú M, Albai G, Dei M, Lai S, Usala G, Lai M, Loi P, Mameli C, Vacca L, Deiana M, Olla N, Masala M, Cao A, Najjar SS, Terracciano A, Nedorezov T, Sharov A, Zonderman AB, Abecasis GR, Costa P, Lakatta E, Schlessinger D. Heritability of cardiovascular and personality traits in 6,148 Sardinians. PLoS Genetics. 2006;2:1207–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blum WF, Englaro P, Hanitsch S, Juul A, Hertel NT, Müller J, Skakkebæk NE, Heiman ML, Birkett M, Attanasio AM, Kiess W, Rascher W. Plasma leptin levels in healthy children and adolescents: Dependence on body mass index, body fat mass, gender, pubertal stage, and testosterone. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1997;82:2904–10. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.9.4251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macy EM, Hayes TE, Tracy RP. Variability in the measurement of C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: Implications for reference intervals and epidemiological applications. Clinical Chemistry. 1997;43:52–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutin AR, Milaneschi Y, Cannas A, Ferrucci L, Uda M, Schlessinger D, Zonderman AB, Terracciano A. Impulsivity-related traits are associated with higher white blood cell counts. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9390-0. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perneger TV. What's wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. British Medical Journal. 1998;316:1236–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ioannidis JPA, Tarone R, McLaughlin JK. The false-positive to false-negative ratio in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2011;22:450–6. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821b506e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman BP, Fiscella K, Duberstein P, Coletta M, Kawachi I. Can the influence of childhood socioeconomic status on men's and women's adult body mass be explained by adult socioeconomic status or personality? Findings from a national sample. Health Psychology. 2009;28:419–27. doi: 10.1037/a0015212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benini ZL, Camilloni MA, Scordato C, Lezzi G, Savia G, Oriani G, Bertoli S, Balzola F, Liuzzi A, Petroni ML. Contribution of weight cycling to serum leptin in human obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2001;25:721–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terracciano A, Schrack JA, Sutin AR, Chan W, Simonsick EM, et al. Personality, Metabolic Rate and Aerobic Capacity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054746. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen WM, Uda M, Albai G, Strait J, Najjar S, Nagaraja R, Orrð M, Usala G, Dei M, Lai S, Maschio A, Busonero F, Mulas A, Ehret GB, Fink AA, Weder AB, Cooper RS, Galan P, Chakravarti A, Schlessinger D, Cao A, Lakatta E, Abecasis GR. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3:1200–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]