Abstract

In this naturalistic study we adopt the lens of interpersonal theory to examine between-and within-person differences in dynamic processes of daily affect and interpersonal behaviors among individuals (N = 101) previously diagnosed with personality disorders who completed daily diaries over the course of 100 days. Dispositional ratings of interpersonal problems and measures of daily stress were used as predictors of daily shifts in interpersonal behavior and affect in multilevel models. Results indicate that ~40%–50% of the variance in interpersonal behavior and affect is due to daily fluctuations, which are modestly related to dispositional measures of interpersonal problems but strongly related to daily stress. The findings support conceptions of personality disorders as a dynamic form of psychopathology involving the individuals interacting with and regulating in response to the contextual features of their environment.

Keywords: Interpersonal Behavior, Affective Instability, Personality Disorders, Interpersonal Problems, Dynamic Processes

Daily Interpersonal and Affective Dynamics in Personality Disorder

Personality disorders (PDs) are defined in terms of stable and cross-situational individual differences of thoughts, feelings, and behavior (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Although stable individual differences in personality exist (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000), and these differences are useful for distinguishing the variants of PD (Samuel & Widiger, 2008; Widiger & Trull, 2007), people with PD experience nuanced and dynamic shifts in experiences and behaviors that seem to be triggered by internal and external contexts. These dynamics are presumed to occur in characteristic sequences of perception, interpretation, and behavioral output that can be described using generalizeable, nomothetic dimensions (Benjamin, 1996; Wright, 2014). The clinician’s task in diagnosing PD for the purpose of making specific hypotheses about functioning and intervention is to describe these sequences (Clarkin, Yeomans, Kernberg, 2006; Linehan, 1993). Empirical models integrating the structure of stable individual differences and dynamic processes therefore are critical for connecting personality science to clinical practice (Hopwood, Zimmermann, Pincus, & Krueger, this issue). Data capture techniques that allow for intensive and repeated measurement of key functional variables, along with innovations in quantitative methodology, have led personality scientists and psychopathologists to begin studying dynamic processes with dimensions established in structural models of basic personality (e.g., McCabe & Fleeson, 2012; Sadikaj et al., 2013). This approach has significant potential to test rich clinical theories regarding the sequences in behavior that characterize PD, uncover new insights about PD phenomena, and identify actionable treatment targets.

A Theoretical Framework for Understanding Dynamic Processes in PD

Navigating the empirical integration of PD structure and processes requires an organizing theory equal to the task. Contemporary integrative interpersonal theory (Pincus, 2005) serves as a well-established framework within which questions about general and specific dynamic processes in personality pathology can be posed because of its shared emphasis on empirically derived structure and inter- and intra-personal processes. The fundamentals of contemporary interpersonal theory can be summarized with four basic assumptions (Pincus & Ansell, 2013). First, the most important expressions of personality (and psychopathology) are interpersonal. This principle defines the focus of the theory, supported by both the essentially social nature of our species (Baumeister & Leary, 1995) and the specifically interpersonal nature of PD dysfunction (Hopwood et al., 2013) as well as interventions known to be effective for PDs (Leichsenring & Leibing, 2003). Second, interpersonal phenomena are not limited to overt expressions of behavior between two (or more) individuals, but also include the internal mental representations of others. Third, interpersonal functioning, across levels of expression (e.g., motives, traits, behaviors, dysfunctions), can be structurally organized using the two primary domains of Agency (dominance, power, mastery, assertion, status) and Communion (affiliation, nurturance, warmth, connectedness, love). Fourth, adaptive and maladaptive dynamics of interpersonal functioning can be understood with reference to normative patterns of interpersonal transaction (e.g., interpersonal complementarity; Sadler, Ethier, & Woody, 2011).

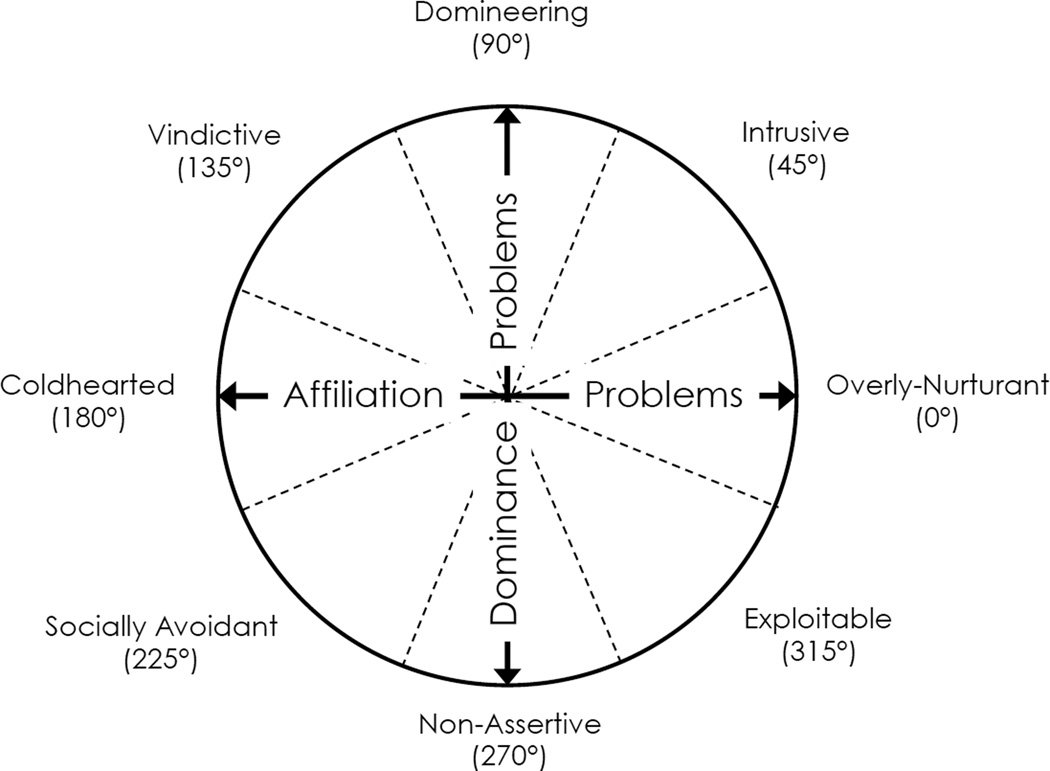

These assumptions provide a coherent and relatively thorough framework for hypotheses regarding both the structure and process of PD (e.g., Horowitz et al., 2006; Kiesler, 1996; Pincus & Ansell, 2013). The interpersonal circumplex (IPC; see Figure 1 as an exemplar) serves as the formal structural model that outlines the primary dimensions, here labeled Dominance and Affiliation (i.e., behavioral manifestations of the broader Agency and Communion, respectively), along which interpersonal functioning is presumed to vary. These two dimensions represent the coordinate system that maps both the between-person structure of dispositional individual difference (Locke, 2011) and the within-person patterning of behavior across time (Fournier et al., 2008). In general, these axes provide a parsimonious common metric that allows for rapid classification of interpersonal functioning that is linked to a well-established nomological net.

Figure 1.

Structural model of interpersonal problems – The Interpersonal Problems Circumplex

This structure provides a solid foundation for integrating dynamic processes as specified by the fourth basic assumption of contemporary integrative interpersonal theory. Traditionally discussed largely in terms of the complementarity principle, which provided hypotheses about overt behavioral match (e.g., Kiesler, 1983), contemporary interpersonal theory has broadened the focus on transactional processes to emphasize the functional purposes of interpersonal behavior via motives and goals (Horowitz et al., 2006). Accordingly, interpersonal motives (broad) and goals (narrow) drive interpersonal behavior within and across situations, and outline the responses from others (and the environment more generally) that satisfy or meet expectations. Broad overarching goals may promote characteristic patterns of behavior across situations in a probabilistic fashion, but given that the contextual features, presses, and contingencies vary across situations, more specific and context-specific goals should stimulate moderation or amplification of specific behaviors. Goal satisfaction, as mediated through responses to one’s own behavior by the other, will lead to internal security and self-esteem as indicated by increases in positive affect. In contrast, goal frustration leads to disappointment and negative affects that prompt the need for some form of regulation. Interpersonal theory is similar to many PD theories in recognizing that regulation of the self (i.e., shifts in social cognition, such as perceptions, goals, expectations) and affect (i.e., modulating one’s inner emotional state and expression) occurs, but also emphasizes field regulation (i.e., modulating the way one behaves and impacts others in interpersonal situations). A central problem in PD involves the inability to effectively modulate behavior, affect, and identity to meet goals that are often conflicting, vacillating, or highly poignant (Hopwood et al., 2013; Horowitz et al., 2006). Thus, in addition to a well-validated structure, contemporary integrative interpersonal theory posits a general heuristic for understanding and predicting dynamic processes that occur between people in their daily lives and in clinical contexts.

Studying Dynamic Processes in Personality and its Pathology

The dynamic processes that form the focus of clinical description and intervention in PDs generally involve an interaction between the individual with PD and the situational contexts within which their symptoms emerge. To the extent that maladaptive behavior is both variable and contextualized in its expression, it is important to sample and analyze behavior in such a way as to reflect these putative processes. The key to studying dynamic processes is leveraging time as a variable through the intensive and repeated assessment of target variables (Larsen, Augustine, & Prizmic, 2009; Moskowitz, Brown, & Cote, 1997; Wright & Markon, in press). A compelling approach for PD research is to capture thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as they are expressed in a patient’s natural environment via momentary or daily questionnaires.

Early basic research on psychological and behavioral processes focused on affect as it varied from day-to-day and moment-to-moment in the real world given the fundamentally variable nature of emotions (e.g., Eid & Diener, 1999; Larsen, 1987; Larsen & Kasimatis, 1990). However, similar approaches were soon applied to interpersonal behavior as well (Brown & Moskowitz, 1998; Moskowitz & Zuroff, 2004). In both domains, it was shown that individuals vary considerably across moments and days in both affect and interpersonal behavior (Eid & Diener, 1999; Moskowitz & Zuroff, 2004). Normative patterns of variability were observable (e.g., weekly entrainment; Larsen, 1987; Brown & Moskowitz, 1998), and yet there was individual heterogeneity in the amount and patterning of this variability (e.g., Kuppens, Van Mechelen, Nezlek, Cossche, & Timmermans, 2007; Larsen & Kasimatis, 1990; Moskowitz & Zuroff, 2004). More recently, this general approach to studying dynamic processes has been applied to studying psychopathology generally (see e.g., Myen-Germeys, 2012 for a review), and personality disorders more specifically (e.g., Ebner-Priemer et al., 2007; Roche, Pincus, Conroy, Hyde, Ram, 2013; Russell et al., 2007).

Research on dynamic processes in PD has initially focused, with few exceptions (e.g., Roche et al., 2013), on borderline personality disorder (BPD; e.g., Trull et al., 2008). BPD provides a compelling first target because it is a construct synonymous with instability across domains (e.g., affect, self-concept, relationships; American Psychiatric Association, 2013, Schmideberg, 1947). Research on affective (e.g., Ebner-Priemer et al., 2007; Trull et al., 2008) and interpersonal instability (Russell et al., 2007) in BPD has motivated the study of contextualized processes (e.g., Sadikaj et al., 2013) central to the construct. Yet, as Fleeson (2001; 2007) has demonstrated with basic personality dimensions, variability across time and context is a core feature of all personality traits. Thus, dynamic processes are general to virtually all domains of personality, which argues for the importance of studying them more broadly in personality pathology (Wright, 2011). In other words, although BPD was a logical place to begin studying dynamic processes in the form of behavioral and affective instability, the emerging results from research on basic personality traits shows that similar processes of interest are likely to be found across disorders.

The Current Study

In the current study, we adopt the lens of contemporary interpersonal theory to expand upon prior work by investigating the dynamics of daily interpersonal behavior and affect as they play out naturalistically in the daily lives of individuals with PDs. Our goal was to examine processes that are general to individuals with PD, as well as those that might be more specific to individuals with certain interpersonal dispositions. Thus, rather than focus on specific diagnostic categories, which can be limited by within-category heterogeneity and between-category covariation of features, we enlisted a group of individuals with a broad sampling of personality pathology, not exclusive to any specific diagnosis. This group of individuals was followed for 100 days and surveyed daily for their ratings of interpersonal behavior and affect. We were motivated to answer several sets of questions. Some questions were largely descriptive, but necessitated by the lack of this type of research in general PD samples, such as: How stable or variable is daily interpersonal behavior and affect among individuals with PD? How are individual differences in dispositionally rated interpersonal problems (Generalized Distress, Dominance, and Affiliative problems) manifested in average levels of interpersonal behavior and affect in daily life? Based on the hypothesis that individuals reporting elevated interpersonal problems of various types will presumably need to engage in more regulatory dynamics, which in turn would manifest in more shifts in behavior, we also asked: Do dispositionally rated interpersonal problems predict instability in behavior and affect? As a more straightforward test of the regulatory hypotheses, we asked: Are daily shifts in interpersonal behavior and affect associated with daily experiences of stress? And are these daily-level associations augmented by level of interpersonal problems? In a series of analyses, we answer each of these questions, focusing on processes that are general to PD, as well as moderation of those processes due to individual dispositions.

Method

Participants

The sample used in this study was collected as part of a project designed to investigate general daily processes of behavior in individuals with PD. As such, recruitment targeted individuals diagnosed with any PD. Participants were recruited from a clinical sample (N=628) enrolled in an ongoing study to improve efficient measurement of PD (Simms et al., 2011; 2015). Participants were recruited into the broader clinical sample by distributing flyers at mental health clinics across Western New York, and were eligible for participation in the parent study if they reported psychiatric treatment within the past two years. Participants received structured clinical interviews for clinical syndromes and PDs by trained assessors using a version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Personality Disorders (SCID-II; First et al., 2002). Only diagnoses of specific PD types were evaluated, and PD-NOS was not evaluated or diagnosed. SCID-II disorder-level Kappas from independent ratings of a subset of participants (n=120) for the 10 DSM-IV PDs were strong (Mdn K = .96; range = .82–1.00). Those who met the threshold for any PD diagnosis on the clinical interview were contacted for possible participation in the current daily diary study. The sole additional requirement for participation was daily Internet access via computer or mobile device.

One hundred and sixteen participants attended the baseline assessment for the daily diary study. Due to the focus on variability in behavior in this study, only participants providing at least 30 days worth of data were included to ensure reliable estimates of variability. Only 15 individuals were excluded for providing less than 30 diaries, resulting in an effective sample size of 101. Of these participants 66 (65.3%) were Female, and the majority reported being either white (82.2%) or African American (14.9%). On average, time between diagnostic interview and the initial assessment in this study was 1.4 years (Range = 1.2–1.7 years; SD = 0.16 years). The PD diagnoses were as follows: 35.6% paranoid, 13.9% schizoid, 16.8% schizotypal, 7.9% antisocial, 36.6% borderline, 2.0% histrionic, 19.8% narcissistic, 53.5% avoidant, 5.9% dependent, 50.5% obsessive-compulsive. The average number of PD diagnoses per participant was 2.4. Additionally, 62.4% were diagnosed with mood disorders, 69.3% with anxiety disorders, 8.9% with psychotic disorders, and 23% with substance/alcohol use disorders. Demographics for the retained sample are presented in Supplemental Table S1. Seventy-two percent of participants reported current mental health care treatment, 14% within the last year, and the remainder longer than one year prior to the daily diary protocol.

Procedure

A complete description of the study was provided and written informed consent was obtained prior to participation. The relevant institutional review board approved all study procedures. Participants attended an initial in-person training and assessment session during which study procedures were explained, and a battery of self-report measures was completed via computer. Starting the evening of the in-person assessment, participants were asked to complete daily diaries via secure website every evening for 100 consecutive days. Surveys were to be completed at (roughly) the same time each day, between 8pm and 12am. However, participants were allowed to deviate from this schedule if necessary (e.g., working nightshift) so long as (a) they completed diaries at the end of their day, and (b) the diaries were completed at roughly the same time each day. Participants received daily email reminders and also were provided several paper diaries they could use in the event of technological difficulties. Compliance rates were very high, with a total of 9,041 diaries completed by participants in this study after data cleaning (Mdn = 94 days, M = 89.5 days, range = 33–101 days, 90% > 60 days), a small fraction of which were done by paper (~2% of completed diaries). Compensation was provided for daily participation at the rate of $100 for ≥ 80% participation, and prorated at $1/day for < 80%. Participation also was incentivized though recurring raffles ($10 drawing every 5 days for those providing at least 4 diaries) and drawings for additional money and tablet computers at the end of the study, with the odds of winning proportionally tied to participation.

Measures

Interpersonal Problems

Interpersonal problems were measured using the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems – Circumplex Scales Short Form (IIP-SC; Soldz et al., 1995). The IIP-SC is a 32-item self-report inventory of interpersonal problems. The IIP-SC contains eight, 4-item scales (i.e., octant scales; see Figure 1) whose internal consistencies ranged from .57 (Vindictive) to .89 (Socially-Avoidant; Mdn = .77; only 1 scale was < .75). Dominant Problems and Affiliative Problems domain scores were calculated from the octant scales using circumplex weighting procedures. Importantly, each domain is bipolar, such that both high and low scores are indicative of interpersonal problems. In addition, generalized interpersonal distress (i.e., severity) was computed as the average octant scale score. Dimensional scores for Dominant and Affiliative Problems provide measures of problems in each domain, net of general severity.

Daily Affect

Daily affect was measured using a subset of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) items. The PANAS uses a 5-point scale (very slightly or not at all, a little, moderately, quite bit, and very much) for participants to rate mood states. Participants were asked to report on their mood “over the last 24 hours.” Based on psychometric work to develop a PANAS short form (Thompson, 2007), daily positive affect was measured as the mean of the following five items: Active, Alert, Attentive, Determined, and Inspired. Daily negative affect was measured as the mean of: Afraid, Ashamed, Hostile, Nervous, and Upset. The resulting affective domains were uncorrelated (r = .04).

Daily Interpersonal Behavior

Daily interpersonal behavior was measured using a subset of the Interpersonal Adjective Scales (Wiggins, 1995) items. One adjective from each octant-scale was provided (e.g., Assertive, Critical, Indifferent, Introverted, etc.), and participants were asked to rate how well each term described their social behavior over the past 24 hours using an 8-point scale ranging from Extremely Inaccurate to Extremely Accurate. Daily dominance and affiliation scores were calculated after first subtracting daily mean endorsement to control for overall endorsement, followed by combining the scores based on circumplex weights. This resulted in two essentially orthogonal dimensions (r = .07) of interpersonal behavior.

Daily Stress

Daily stress was measured using a self-report version of the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE; Almeida et al., 2002), which consists of seven questions that ask whether specific stressful events have occurred within the last 24 hours. The events and the percentage of days each was endorsed were as follows: 1. Having had an argument or disagreement with someone (19%), 2. Something occurring that could have lead to an argument or disagreement but it was allowed to pass (25%), 3. A stressful event at work or school (15%), 4. A stressful event at home (25%), 5. Experiencing discrimination on the basis of age, sex, or race (4%), 6. Something stressful happening to a close friend or relative (14%), 7. anything else that most people would consider stressful (19%). Endorsed events then were rated for severity on a 4-point scale with the anchors of Not at all, Not Very, Somewhat, and Very. We used the average of the rated severity, across items, as an index of daily perceived stress.

Results

Due to the sequential nature of our analyses, which follow the questions posed in the introduction section, we describe analyses and report their results concurrently in the following section. All analyses were conducted in Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, 2013).

How stable or variable is daily interpersonal behavior and affect among individuals with PD?

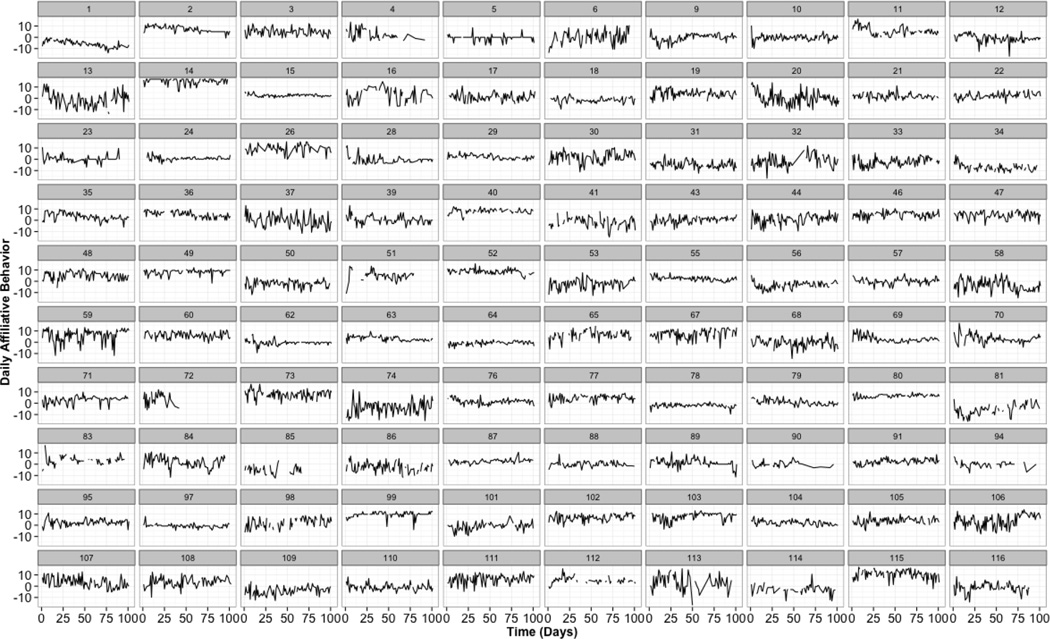

To answer this question we partitioned the total variances into the proportion accounted for by individual differences (i.e., between-person differences in average levels) and daily fluctuations (i.e., the daily within-person variability around individual averages) by calculating the intraclass correlation (ICC) from unconditional multilevel models (MLMs) with daily ratings of interpersonal behavior and affect (Level 1) nested within individuals (Level 2). The ICC from a standard two-level MLM reflects the proportion of variance that is attributable to the differences among Level 2 units—in this case, the between-person variance. Daily dominant behavior exhibited the lowest amount of between-person variance (i.e., the highest amount of within-person variability; ICC = .49; S.E. = .04; 95% CI = .42–.56), followed by daily affiliative behavior (ICC = .56; S.E. = .04; 95% CI = .49–.62), daily negative affect (ICC = .58; S.E. = .03; 95% CI = .51–.65) and daily positive affect (ICC = .58; S.E. = .03; 95% CI = .51–.65). The results demonstrate a substantial amount of daily variability in interpersonal behavior and affect among individuals with PDs in addition to clear individual differences in average daily levels. Figure 2 provides the study participants’ individual time series to fully illustrate the dramatic variability in affiliative behavior both between and within individuals in this study (See Supplementary Figures S1, S2, S3, for the remaining domains).1

Figure 2.

Diagram of individual time-series of daily affiliative behavior. Values could range from −16 to 16.

Are dispositionally rated interpersonal problems manifested in average levels of interpersonal behavior and affect in daily life?

The ICCs offer prime facie evidence that dynamic processes are playing out at the daily level, and hint at the possibility that there are important individual differences in, and daily triggers for, those processes. However, prior to investigating predictors of daily dynamics, we first examined whether the IIP-SC, which has been used extensively in the investigation of PDs assessed cross-sectionally (e.g., Pincus & Wiggins, 1990; Wright et al., 2012), similarly predicts daily interpersonal behavior and daily affect. We hypothesized that the three primary dimensions of the IIP-SC—Generalized Distress, Dominant Problems, and Affiliative Problems—would relate to average daily behavior in specific ways. We predicted that baseline Dominant Problems would specifically predict higher daily dominant behavior, baseline Affiliative Problems would specifically predict greater reports of daily Affiliative behavior, and baseline Generalized Distress would relate to daily Negative Affectivity. We also predicted that Generalized Distress may be related to greater submissive (i.e., negatively related to daily dominance) and cold (i.e., negatively related to daily affiliation) behavior given that personality pathology that is most strongly related to distress is generally associated with the submissive or cold locations on the Circumplex (Pincus & Wiggins, 1990; Wright, Hallquist, Morse, et al., 2013). We predicted no relation between positive affect and any of the IIP scales.

To test these associations, we estimated a series of conditional MLMs, predicting individual differences in average daily interpersonal behavior and affect (i.e., random intercepts) from dispositional ratings of IIP domain scores (Level 2 predictors). In addition, Level 1 covariates included age and gender, as well as time to account for linear trends in the data, and weekend vs. weekday to account for differences in daily endorsement of interpersonal behavior and affect that is due to well-established social rhythms (Brown & Moskowitz, 1998; Larsen & Kisamatis, 1990), as opposed to individual differences in behavior. No effect for gender was observed in any of the models. Age positively predicted daily positive affect (β = .014, SE = .005, p = .010) exclusively. There was a significant decrease in overall reporting of negative affect as the study progressed (Time β = −.001, SE = .0005, p = .007), but this effect was not observed for the other variables, guarding against interpretations of participant reactivity or fatigue effects. Finally, lower levels of negative affect (β = −.061, SE = .014, p = .01), positive affect (β = −.046, SE = .023, p = .048), and dominant behavior (β = −.347, SE = .095, p < .001) were observed on weekends relative to weekdays, consistent with prior research.

Results are presented in Table 1. As predicted, IIP-SC Dominance exclusively predicted higher daily levels of dominant behavior, and IIP-SC Affiliation exclusively predicted higher daily Affiliative behavior. Also as hypothesized, IIP-SC Generalized Distress predicted higher daily negative affect, daily submissiveness, and cold or disaffiliative behavior. As expected, the IIP-SC scales did not predict positive affect.

Table 1.

Predicting Individual Differences in Daily Interpersonal Behavior and Affect from IIP Domains

| Daily Interpersonal Behavior | ||||||

| Dominance | Affiliation | |||||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | p | Estimate | S.E. | p | |

| IIP Distress | −.67 | .30 | .026 | −1.80 | .46 | < .001 |

| IIP Dominance | 1.91 | .38 | < .001 | −.95 | .57 | .097 |

| IIP Affiliation | .57 | .41 | .163 | 1.67 | .62 | .007 |

| Random Effects | Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI | Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 5.78 | .86 | 4.31, 7.75 | 12.20 | 1.80 | 9.14, 16.29 |

| Daily Affect | ||||||

| Negative Affect | Positive Affect | |||||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | p | Estimate | S.E. | p | |

| IIP Distress | .42 | .07 | < .001 | −.06 | .09 | .480 |

| IIP Dominance | .16 | .09 | .084 | .13 | .11 | .233 |

| IIP Affiliation | .07 | .10 | .500 | .19 | .12 | .121 |

| Random Effects | Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI | Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI |

| Intercept | .31 | .04 | .23, .40 | .51 | .07 | .39, .67 |

Note. N = 101. Significant values bolded. IIP = Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. S.E. = Standard Error; All parameters reported from multilevel models which simultaneously included all reported predictors, as well as gender, age, time, and weekend vs. weekday as unreported covariates.

Do dispositionally rated interpersonal problems predict instability in behavior and affect?

To test whether individual differences in interpersonal problems were predictive of dynamic processes in behavior we adopted a successive differences approach (see e.g., Jahng et al., 2008; Trull et al., 2008), which accounts for both temporal ordering and amplitude of fluctuation (i.e., it matters not only how different a score at a given time point is from others, but also when in the time-series it occurs).

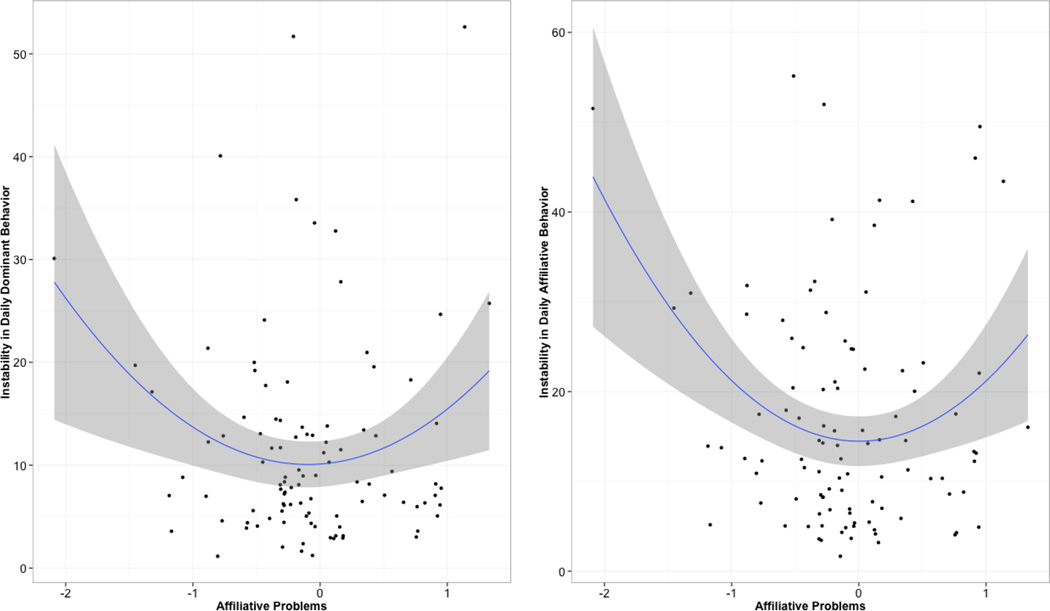

Here we examine successive differences using a MLM framework given that individuals differ in the overall number of time-points they contributed, and MLMs account for these differences. Specifically, the square of successive differences (SSD), calculated by subtracting each time-point’s score at time t-1 from the score at time t, was the outcome. When missing data created a gap in an individual’s time-series, the next available time-point was treated as the new t, without a t-1 to create a SSD. As Jahng et al. (2008) note, the distribution of SSDs of this type are likely to be highly non-normal (i.e., no negative values; highly positively skewed), and are likely to fit a Gamma distribution. We observed this pattern in our data, and therefore we used a generalized MLM with a Gamma error distribution and a log link (see Jahng et al., 2008 for a detailed description of this model) available in Stata 13.1’s MEGLM package. Separate MLMs were estimated for each outcome (i.e., daily dominance, affiliation, negative affect, positive affect). The estimated MLMs were intercept-only models, with a randomly varying intercept to capture individual differences in average SSDs. Individuals with higher scores have more unstable behavior and affect across daily assessments. We then entered the IIP-SC scales as predictors of individual differences in average SSD. Because the IIP-SC Dominance and Affiliation Problem scales are truly bipolar (i.e., with greater pathology reflected at each end, but with opposing content), we reasoned that it was possible that either extreme could be associated with greater instability. As such, we entered quadratic terms for both IIP-SC Dominance and Affiliation, but only the linear effect for IIP-SC Generalized Distress. As in the previous models, we controlled for time, weekend days, gender, and age. Neither gender nor age related to instability in any of the outcome variables. However, time uniformly related to lower instability, and only instability of negative affect was lower on weekends.

On the whole, the IIP-SC scales did not predict a great deal of variability in SSDs. However, IIP-SC Generalized Distress did predict daily negative affect instability (β = .45, SE = .12, p < .001). IIP-SC Dominance also predicted positive affect instability (β = .24, SE = .12, p = .043). Notably, instability in both daily dominance (β = .29, SE = .14, p = .041) and affiliation (β = .31, SE = .14, p = .024) were predicted by quadratic IIP-SC Affiliation (full results are in Table S2). A visual scan of the plotted regression lines (see Figure 3) indicates that it is those individuals at high and low IIP-SC Affiliation that are higher on interpersonal instability.2

Figure 3.

Diagram of individual differences in instability (square of successive differences) regressed on affiliative problems.

Are daily shifts in interpersonal behavior and affect associated with daily stress?

Shifting from features of the individual that predict instability to contextual and time varying factors, we next examined whether daily experiences influenced instability in daily interpersonal behavior and affect. We focus on perceived stress as a predictor because it varies considerably across days, and is presumed to trigger various regulatory processes. In the following MLMs we include the individual mean of stress to account for individual differences in the experience of stress, as well as the daily deviations from an individual’s average to account for daily fluctuations. We first estimate MLMs predicting SSDs, in line with the approach above. This allowed us to determine whether stress is related to overall instability scores at the individual and daily levels. Results indicated that mean stress predicted greater average instability only in daily interpersonal dominance (β = .13, SE = .03, p < .001) and affiliative behavior (β = −.10, SE = .03, p = .005). However, daily stress fluctuations predicted instability in dominance (β = .03, SE = .01, p < .001) affiliation (β = .04, SE = .01, p < .001), negative affect (β = .13, SE = .01, p < .001) and positive affect (β = .02, SE = .01, p < .018).

Thus, very generally, daily stress predicts greater shifts in interpersonal behavior and affect. Although informative, this does not elucidate whether affect and behavior shifts in a particular direction in response to stress. To address this, we calculated difference scores between consecutive days, without squaring, and used these scores as outcomes. These new scores provide directional shifts (i.e., increases or decreases) between any given time point t-1 and t. We then posed two questions of the data by entering stress at time t, and stress at time t-1. First, including stress at time t answers the question: What is the response to daily stress when it occurs? Second, including stress at time t-1 answers the question: What is the response after stress has passed? Importantly, in these models daily fluctuations in stress (at both t and t-1) are random effects, allowing for individual differences in the relationship between daily stress and interpersonal and affective responses. We again include an individual’s average stress and the daily deviations from that average (at t-1 and t) as predictors.

Results for the coefficients of primary interest are presented in Table 2. Given that for an individual there should be equivalence in increases and decreases in a given behavior over time the point estimate for the intercept of directional shifts was uniformly zero and therefore is not reported. The same holds for individual differences in this estimate (i.e., Level 2 variance). None of the aforementioned covariates were significant predictors of directional shifts. When considering daily stress as a predictor of directional shifts in behavior and affect, we found an opposite pattern of prediction for stress at time t and t-1 as predictors. Stress at time t predicted decreased affiliation, and increased dominance, negative affect, and positive affect relative to the day prior (i.e., shift from time t-1). In contrast, stress at time t-1 predicted an increase in affiliative behavior, and decreases in dominance, negative affect, and positive affect the following day (t). Importantly, this pattern holds whether both predictors are entered simultaneously or in a univariate fashion in separate models. Furthermore, significant random effects were observed (i.e., Level 2 variances), indicative of individual differences in this within-person association among stress and the behavioral/affective response. These opposing patterns are suggestive of a stress cycle, with an average shift in one’s behavioral profile associated with dealing with stress on a given day, which then resolves the day after having been stressed.

Table 2.

Predicting Directional Daily Shifts in Interpersonal Behavior and Affect From Current and Previous Day’s Stress

| Shifts in Daily Interpersonal Behavior (t – t-1) | ||||||

| Dominance | Affiliation | |||||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | p | Estimate | S.E. | p | |

| Stresst | .208 | .026 | < .001 | −.317 | .033 | < .001 |

| Stresst-1 | −.217 | .027 | < .001 | .365 | .035 | < .001 |

| Mean Stress | .000 | .018 | .999 | −.002 | .021 | .910 |

| Random Effects | ||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI | Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | .000 | -- | -- | .000 | -- | -- |

| Stresst | .031 | .009 | .017, .054 | .058 | .015 | .034, .098 |

| Stresst-1 | .034 | .010 | .020, .058 | .068 | .018 | .041, .113 |

| Shifts in Daily Affect (t – t-1) | ||||||

| Negative Affect | Positive Affect | |||||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | p | Estimate | S.E. | p | |

| Stresst | .105 | .006 | < .001 | .013 | .004 | .002 |

| Stresst-1 | −.107 | .006 | < .001 | −.015 | .005 | .001 |

| Mean Stress | .000 | .003 | .888 | .002 | .004 | .617 |

| Random Effects | ||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI | Estimate | S.E. | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | .000 | -- | -- | .0000 | -- | -- |

| Stresst | .002 | .0005 | .001, .003 | .0005 | .0002 | .0002, .0013 |

| Stresst-1 | .002 | .0005 | .002, .003 | .0008 | .0003 | .0004, .0017 |

Note. S.E. = Standard Error, CI = 95% Confidence Interval. All parameters reported from multilevel models which simultaneously included all reported predictors, as well as gender, age, time, and weekend vs. weekday as unreported covariates.

And are these relationships augmented by level of interpersonal problems?

Finally, given that individuals differed significantly on the within-person link between stress and interpersonal behavior/affect, we tested whether IIP-SC scales moderated the relation between stress and shifts in interpersonal behavior and affect. Although two effects trended toward significance, on the whole these effects were non-significant. The marginal effects suggested that (1) baseline Dominance Problems amplified the dominance response to stress, and (2) baseline Affiliative Problems amplified negative affect in response to stress. However, overall our results suggested that the stress processes did not vary greatly by interpersonal disposition.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that daily interpersonal behavior and affect varies considerably among individuals with PD, indicative of dynamic processes that play out from day to day. Additionally, dispositionally rated interpersonal problems are related to daily averages in behavior in expected ways, as well as fluctuations of behaviors, suggesting that these processes differ as a function of individual differences in interpersonal style. Further, we demonstrated that daily shifts in behavior are strongly related to the experience of daily stress, although these processes appear more general as opposed to specifically related to interpersonal problem styles. We next consider each of these findings in more detail.

Within-person variability over time is a necessary condition for studying dynamic processes. On the one hand, that individuals vary in behavior across time and situations may be so intuitively obvious as to seem uninteresting. On the other hand, from an empirical perspective, it is only by verifying and quantifying this variability that important questions regarding instability can be posed and answered. For instance, to say that PD individuals are rigid and inflexible, or conversely, labile and erratic, are actually assertions about variance of behavior, not average levels or extremity. Examining PD processes therefore compels the measurement of behavior intensively and repeatedly so that these claims can be tested (Moskowitz et al., 2009). Here we demonstrate that a substantial proportion (42%–51%) of overall variability in daily interpersonal behavior and affect in this sample of individuals with any PD comes from day-to-day fluctuations within-person as opposed to between-person differences in the averages. Our results are highly concordant with previously published findings from non-clinical samples (ICCs for affect = .52–.56; e.g., Charles & Almeida, 2006; Merz & Roesch, 2011), suggesting that on average individuals with PD are no more or less variable than others.3 This finding, in concert with the growing body of basic personality work on this topic (e.g., Fleeson & Gallagher, 2009), shows that considerable variability in behavior is an aspect of functioning general to all individuals, whether they are diagnosed with a PD or not. However, individual differences in variability may be an important differentiating feature worth investigating in its own right (Larsen, 1989). Indeed, intraindividual variability (or lack thereof) across domains can be presumed to hold important clinical information, such that instability signals the need for improved regulation, whereas stability may necessitate active perturbation and disruption. This rich diversity in patterns of within-person fluctuation in behavior/affect is perhaps demonstrated best by the individual time-series in Figure 2 (see also Supplementary Figures S1, S2, and S3).

With this finding in hand, we next investigated dispositional (i.e., interpersonal problem dimensions) and time-varying contextual features (i.e., daily stress) as predictors of gross instability and specific patterns of variability in interpersonal behavior and affect over time. Individual daily averages in interpersonal behavior and affect were related as expected to dispositionally rated Dominance Problems (.67 SD increase in daily dominant behavior per 1 SD increase in IIP Dominance), Affiliative Problems (.42 SD increase in daily affiliative behavior per 1 SD increase in IIP Affiliation), and Generalized Interpersonal Distress (.65 SD higher negative affect, .24 SD increase in submissive, and .46 SD increase in cold behavior per SD increase in IIP Distress). The results supported subsequent investigations into the relation between dispositions and daily variability. Interpersonal theory proposes that individuals engage in a variety of self, affect, and field (i.e., interpersonal) regulatory strategies when encountering frustrated goals or adversity (Hopwood et al., 2013; Horowitz, 2004; Kiesler, 1996; Pincus et al., 2010). Therefore, we hypothesized that individuals higher in interpersonal problems would report greater instability in behavior reflecting their more frequent need to regulate themselves and their interpersonal field.

Regarding interpersonal behavioral instability, we found a quadratic effect for Affiliative Problems on both daily dominance and affiliation. Individuals high on either pole of Affiliative Problems (i.e., overly warm or overly cold) exhibited greater instability of interpersonal behavior. The effects are substantial, such that a 1 SD difference in Affiliative Problems is associated with 43% and 32% greater instability in affiliative and dominant behavior respectively. At 2 SDs, the differences in instability are 266% and 225% relative to the average. This suggests that those individuals who have difficulties managing issues of interpersonal closeness and separation exhibit markedly greater interpersonal behavior instability on average. We interpret this finding as reflecting greater amounts of interpersonal field dysregulation among individuals at the extremes of affiliative interpersonal problems. Of note, this effect emerged for both daily affiliative and dominant behavior, suggesting these individuals not only shift between interpersonal closeness and distance, but also between assertiveness and passivity when regulating their interpersonal field. However, no similar effect was found for Dominant Problems. It is possible that regulatory processes related to dominance operate on a different time-scale, or are less frequently evoked, and therefore dominant problems do not emerge as a significant predictor of daily variability as with affiliative problems. It is also possible that issues of status, hierarchy, and control are less salient for this sample. We also found that as Generalized Interpersonal Distress increased, so too did negative affect instability (a 58% increase per SD increase in IIP Distress). That Generalized Interpersonal Distress relates to negative affect instability is not surprising, given that interpersonal distress strongly relates to negative emotionality and disorders defined by affect instability (e.g., BPD; Wright, Hallquist, Morse, et al., 2013).

We next asked whether other aspects of an individual’s daily life were predictive of day-to-day instability in behavior/affect. Stress was chosen as the daily level predictor due to the assumption that, very generally, it catalyzes various regulatory processes. Taken together with theories of personality pathology that posit PD as reflecting maladaptive regulation (e.g., Linehan, 1993; Hopwood et al., 2013), among other impairments, daily stress therefore serves a key time-varying contextual feature to enlist in the study of dynamic processes in PD. And, as expected, we found that daily stress predicted larger instability in behavior, regardless of the interpersonal or affective domain being sampled. Moreover, we found that stress not only predicted greater shifts in daily behavior/affect, but also that it was associated with a particular “signature” of behavior/affect. Specifically, the experience of stress on a given day leads to increased dominance and decreased affiliation, along with increased negative and positive affect relative to the day prior. The opposite shift in behavior is predicted by the prior day’s stress, such that the day after individuals were likely to shift toward being less dominant, more affiliative, and experience lower levels of negative and positive affect. These results are consistent with a homeostatic cycle of interpersonal and affective perturbation due to stress, followed by regulation and return to baseline.

Several aspects of this finding deserve elaboration. At the most mundane level, we must note that our measure of positive affect is primarily a measure of activation as opposed to positive valence, which likely explains why it is positively associated with stress. The finding that individuals respond with negative affect to stress is not novel, and has been long demonstrated with similar methods in the basic personality literature (e.g., Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995; Suls & Martin, 2005). More interestingly, the interpersonal aspects of the stress response suggest that on average individuals with PDs enact a self-protective stance in response to stress, becoming more dominant and separate. The inverse is true of the day following stressful events, which likely reflect a de-escalation of the defensive interpersonal stance, but may also reflect appeasement strategies, insofar as the stress was related to interpersonal conflict. Beyond these averages in behavioral and affective responses to stress, we found significant individual differences in the within-person link between stress and behavior/affect. In other words, some individuals respond more strongly to stress in these ways than others. Which raises questions about which types of variables moderate or amplify the modal stress response in PD (e.g., Suls & Martin, 2005). To the extent that moderation is present, contemporary interpersonal theory would predict that individuals react to stress in a manner that is more similar to their interpersonal dispositions. However, we found only modest support for the hypothesis that the interpersonal dispositions (at least as measured by the IIP-SC) moderated this within-person link.

The current study benefitted from a relatively large sample of individuals diagnosed with PDs who provided daily diaries at a high-rate of compliance over a long study period (100 days). However, the results must be considered in the context of several limitations. For one, there was a relatively large gap between the time in which participants were assessed for PDs, and when they completed the daily diary study (~1.4 years). During this time, any manner of internal and external influences may have lead to changes in their clinical and psychological profile. Although detailed information on clinical interventions is not available, we note that on the average participants enrolled in this phase of the study were highly stable across the intervening time period on a host of PD and functioning variables, suggesting that they remained largely the same in terms of their features (see Wright, Calabrese, et al., in press for details).

In addition, our results are exclusive to the domain of self-report, and clinical experience, theory, and past research (e.g., Klonsky et al., 2002; Leary, 1957; Pincus, 2005) all would suggest that among individuals with PD, discrepancies exist between an individual’s self-perception, and the perception others hold of their behavior. Therefore the generalizability of our results are to the individual’s perspective on their behavior as they experience it. Future research should endeavor to capture the perspectives of multiple informants in order to fully appreciate dynamic processes in PD (e.g., Roche et al., 2014). This is not without challenges, as other informants only have access to the information they themselves are present for and will be subject to perceiver effects. Nevertheless, the use of close significant others (e.g., spouses, cohabiting romantic partners) may be able to provide some perspective on this issue. Alternatively, or in conjunction, research designs may be able to leverage measures that vary in their focus, endeavoring to capture potentially divergent levels of experience, including motivations, goals, perceptions and behavior to provide richer perspectives on individual processes. Yet, that self-reports capture the individual’s unique perspective on their daily experience should not diminish their value, because it is often the individual’s experience that is precisely what clinicians are working directly with in assessment and treatment. Knowing the pattern of experienced behavior for an individual when they experience stress would provide a clinician with an invaluable target.

We investigated dynamic processes at the daily level. Yet it is clear that important dynamic processes play out across several time-scales, ranging from the momentary (e.g., Russell et al., 2007; Sadkiaj et al., 2013; Trull et al., 2008) to the yearly (Morey & Hopwood, 2013), and everything in between (e.g., Wright et al., 2013; Wright et al., in press). Although end-of-day diaries are commonly used in the study of the types of processes examined here (e.g., Mroczek & Almeida, 2004; Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995), researchers are encouraged to give deep consideration to the precise level of temporal fidelity necessary to target the processes of interest in their study (Collins, 2006). Thus, our results generalize only to the daily level, which allows for the study of dynamics that are not possible in cross-sectional studies and those of less frequent assessment, but will miss processes that play out on a briefer time scale.

Additionally, we focused on perceived stress as a general phenomenon, and did not tease apart more nuanced contextual differences that might lead to differential responses to stress. For instance, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that interpersonal stressors hold particular importance for personality pathology relative to other forms of psychopathology, and differences may be observed between interpersonal and non-interpersonal stressors among individuals with PDs. More nuanced still would be greater contextual fidelity within interpersonal stress, differentiating between perceptions of conflict, withdrawal, power struggles, and so forth (cf. Sadikaj et al., 2013). Similarly, we emphasized the measurement of very broad domains of behavior and affect, and there are likely interesting differences to be uncovered by investigating more specific behaviors/affect that are subsumed within these domains (e.g., shame vs. anger vs. anxiety). Future research should examine more narrowly measured behaviors as well as broad domains. We plan to pursue these questions in subsequent investigations with this sample.

Finally, although interpersonal dysfunction is widely recognized as one of the hallmarks of personality pathology, it has been pointed out that there are other domains of PD not well captured by the interpersonal model we employ here (Widiger & Hagemoser, 1997). Thus, it is possible that measures that capture other domains of personality pathology (e.g., impulsivity, psychoticism) may uncover moderating effects that we did not find here. Future research should investigate additional dispositional measures. However, it may be that these effects did not emerge here because this sample was comprised entirely of those with PD, and thus range restriction occurred that would be clarified by sampling from those without significant pathology.

Conclusion

Clinical theories of personality pathology emphasize the importance of complex dynamic processes of the individual interacting with and regulating in response to internal cues and external features of the social environment. However, fulfilling the scientific promise of these rich clinical theories generally has lagged when facing the challenges of systematic empirical investigation. This has been changing in recent years as data collection and analytic advances have been catching up with theory. Here we adopted the lens of contemporary interpersonal theory to naturalistically study interpersonal and affective dynamics in a large group of individuals with PDs. We employed daily measurements of the domains of the interpersonal and affective circumplex, which each can additionally be understood as variants of the domains found in broad dimensional trait models (e.g., the Five-Factor Model). The findings largely support the general assumptions of interpersonal theory of PD, while also offering new insights into both general and specific interpersonal and affective processes that play out on the daily level that are likely to be highly informative for the conceptualization, assessment, and treatment of PD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grants F32 MH097325 (Wright) and R01 MH080086 (Simms). The views contained are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding source.

Footnotes

For the purposes of the time-series diagrams one participant was chosen at random and excluded so that there would be an even number of columns and rows (i.e., presented n = 100).

Analyses were re-run after winsorizing three outliers, one in average affiliation SSD and two in average dominance SSD. Results were unchanged. No outlers were found in the IIP dimensions.

We were unable to find published results for daily interpersonal behavior, but presume the similarity will hold.

Contributor Information

Aidan G.C. Wright, University of Pittsburgh

Christopher J. Hopwood, Michigan State University

Leonard J. Simms, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

References

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, Kessler RC. The daily inventory of stressful events an interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment. 2002;9(1):41–55. doi: 10.1177/1073191102091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological bulletin. 1995;117(3):497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin LS. Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1995;69(5):890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Moskowitz DS. Dynamic stability of behavior: The rhythms of our interpersonal lives. Journal of personality. 1998;66(1):105–134. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Almeida DM. Daily reports of symptoms and negative affect: Not all symptoms are the same. Psychology and Health. 2006;21(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin JF, Yeomans FE, Kernberg OF. Psychotherapy for borderline personality: Focusing on object relations. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Kleindienst N, Welch SS, Reisch T, Reinhard I, Bohus M. State affective instability in borderline personality disorder assessed by ambulatory monitoring. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37(07):961–970. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid M, Diener E. Intraindividual variability in affect: Reliability, validity, and personality correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(4):662. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. New York: (SCID-I/P) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson W. Toward a structure-and process-integrated view of personality: Traits as density distributions of states. Journal of personality and social Psychology. 2001;80(6):1011–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson W. Situation-based contingencies underlying trait-content manifestation in behavior. Journal of personality. 2007;75(4):825–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson W, Gallagher P. The implications of Big Five standing for the distribution of trait manifestation in behavior: fifteen experience-sampling studies and a meta-analysis. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2009;97(6):1097. doi: 10.1037/a0016786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier MA, Moskowitz DS, Zuroff DC. Integrating dispositions, signatures, and the interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:531–545. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Wright AGC, Ansell EB, Pincus AL. The interpersonal core of personality pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2013;27(3):271–295. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2013.27.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Zimmermann J, Pincus AL, Krueger RF. Connecting Personality Structure and Dynamics: Towards a More Evidence Based and Clinically Useful Diagnostic Scheme. Journal of Personality Disorders. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2015.29.4.431. (under review). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Wilson KR, Turan B, Zolotsev P, Constantino MJ, Henderson L. How interpersonal motives clarify the meaning of interpersonal behavior: A revised circumplex model. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10(1):67–86. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng S, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Analysis of affective instability in ecological momentary assessment: Indices using successive difference and group comparison via multilevel modeling. Psychological methods. 2008;13(4):354. doi: 10.1037/a0014173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler DJ. The 1982 interpersonal circle: A taxonomy for complementarity in human transactions. Psychological Review. 1983;90(3):185. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler DJ. Contemporary interpersonal theory and research: Personality, psychopathology, and Psychotherapy. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Informant-reports of personality disorder: Relation to self-reports and future research directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(3):300–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Van Mechelen I, Nezlek JB, Dossche D, Timmermans T. Individual differences in core affect variability and their relationship to personality and psychological adjustment. Emotion. 2007;7(2):262–274. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ. The stability of mood variability: A spectral analytic approach to daily mood assessments. Journal of Personality and Social psychology. 1987;52(6):1195. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Augustine AA, Prizmic Z. A process approach to emotion and personality: Using time as a facet of data. Cognition and Emotion. 2009;23(7):1407–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Kasimatis M. Individual differences in entrainment of mood to the weekly calendar. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(1):164–171. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring F, Leibing E. The effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders: a meta-analysis. American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1223–1232. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Locke KD. Circumplex measures of interpersonal constructs. In: Horowitz LM, Strack S, editors. Handbook of interpersonal psychology. Hoboken: Wiley; 2011. pp. 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KO, Fleeson W. What is extraversion for? Integrating trait and motivational perspectives and identifying the purpose of extraversion. Psychological science. 2012;23(12):1498–1505. doi: 10.1177/0956797612444904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EL, Roesch SC. Modeling trait and state variation using multilevel factor analysis with PANAS daily diary data. Journal of research in personality. 2011;45(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Hopwood CJ. Stability and change in personality disorders. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2013;9:499–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DS, Brown KW, Côté S. Reconceptualizing stability: Using time as a psychological dimension. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1997:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DS, Russell JJ, Sadikaj G, Sutton R. Measuring people intensively. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2009;50(3):131. [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DS, Zuroff DC. Flux, pulse, and spin: dynamic additions to the personality lexicon. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2004;86(6):880–893. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.6.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Almeida DM. The effect of daily stress, personality, and age on daily negative affect. Journal of personality. 2004;72(2):355–378. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I. Psychiatry. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, editors. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 636–650. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL. A contemporary integrative interpersonal theory of personality disorders. In: Lenzenweger M, Clarkin J, editors. Major theories of personality disorder. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 282–331. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL, Ansell EB. Interpersonal theory of personality. In: Suls J, Tennen H, editors. Handbook of Psychology Vol. 5: Personality and social psychology. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. pp. 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL, Wiggins JS. Interpersonal problems and conceptions of personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1990;4(4):342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: a quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological bulletin. 2000;126(1):3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche MJ, Pincus AL, Conroy DE, Hyde AL, Ram N. Pathological narcissism and interpersonal behavior in daily life. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2013;4(4):315. doi: 10.1037/a0030798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche MJ, Pincus AL, Rebar AL, Conroy DE, Ram N. Enriching psychological assessment using a person-specific analysis of interpersonal processes in daily life. Assessment. 2014;21(5):515. doi: 10.1177/1073191114540320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JJ, Moskowitz DS, Zuroff DC, Sookman D, Paris J. Stability and variability of affective experience and interpersonal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(3):578–588. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadikaj G, Moskowitz DS, Russell JJ, Zuroff DC, Paris J. Quarrelsome behavior in borderline personality disorder: Influence of behavioral and affective reactivity to perceptions of others. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2013;122(1):195–207. doi: 10.1037/a0030871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmideberg M. The treatment of psychopaths and borderline patients. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1947;1:45–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1947.1.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer S, Streeck U, Jaeger U, Masuhr O, Warwas J, Leichsenring F, Leibing E. Patterns of interpersonal problems in borderline personality disorder. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2013;201(2):94–98. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182532b59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR: personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms LJ, Goldberg LR, Watson D, Roberts JE, Welte J. The CAT-PD Project: Introducing an Integrative Model & Efficient Measure of Personality Disorder Traits; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Personality Assessment; Arlington, VA. 2014. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Soldz S, Budman S, Demby A, Merry J. Representation of personality disorders in circumplex and five-factor space: Explorations with a clinical sample. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(1):41. [Google Scholar]

- Soldz S, Budman S, Demby A, Merry J. A short form of the inventory of interpersonal problems circumples scales. Assessment. 1995;2(1):53–63. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release. Vol. 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Martin R. The daily life of the garden-variety neurotic: Reactivity, stressor exposure, mood spillover, and maladaptive coping. Journal of personality. 2005;73:1485–1510. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ER. Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2007;38(2):227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Solhan MB, Tragesser SL, Jahng S, Wood PK, Piasecki TM, Watson D. Affective instability: Measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(3):647–661. doi: 10.1037/a0012532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Hagemoser S. Personality disorders and the interpersonal circumplex. In: Plutchick R, Conte H, editors. Circumplex models of personality and emotions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 299–326. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ. Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: Shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist. 2007;62:71–83. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS. Interpersonal Adjective Scales: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC. Quantitative and qualitative distinctions in personality disorder. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2011;93(4):370–379. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.577477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC. Integrating trait and process based conceptualizations of pathological narcissism in the DSM-5 era. In: Besser A, editor. Handbook of psychology of narcissism: Diverse perspectives. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2014. pp. 153–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Calabrese WR, Rudick MM, Yam WH, Zelazny K, Rotterman J, Simms LJ. Stability of the DSM-5 Section III pathological personality traits and their longitudinal associations with functioning in personality disordered individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/abn0000018. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Hallquist MN, Beeney JE, Pilkonis PA. Borderline personality pathology and the stability of interpersonal problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(4):1094–1100. doi: 10.1037/a0034658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Hallquist MN, Morse JQ, Scott LN, Stepp SD, Nolf KA, Pilkonis PA. Clarifying interpersonal heterogeneity in borderline personality disorder using latent mixture modeling. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2013;27(2):125–143. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2013.27.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Markon KE. Longitudinal designs. In: Norcross JC, VandenBos GR, Freedheim DK, editors. American Psychological Association handbook of clinical psychology, Vol. II. Clinical psychology: Theory and research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Pincus AL, Hopwood CJ, Thomas KM, Markon KE, Krueger RF. An interpersonal analysis of pathological personality traits in DSM-5. Assessment. 2012;19(3):263–275. doi: 10.1177/1073191112446657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Scott LN, Stepp SD, Hallquist MN, Pilkonis PA. Personality pathology and interpersonal problem stability. Journal of Personality Disorders. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_171. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.