Watch a video presentation of this article

Watch the interview with the author

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha‐fetoprotein

- cccDNA

covalently closed circular DNA

- CU‐HCC

Chinese University‐HCC score

- DAA

direct‐acting antiviral

- GAG‐HCC

Guide with Age, Gender, HBV DNA, Core promoter mutations, and Cirrhosis

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- LSM

liver stiffness measurement

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- REACH‐B

Risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B

- REVEAL‐B/REVEAL‐HCV

Risk Evaluation of Viral Load Elevation and Associated Liver Disease/Cancer in HBV/HCV

- SVR

sustained virological response

- TGF‐β

transforming growth factor β.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a growing clinical problem, as the second leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide (GLOBOCAN, http://globocan.iarc.fr) and one of the only increasing causes of cancer‐related mortality in the United States.1 The landscape of clinical demographics has been changing with the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NAFLD/NASH), for which HCC risk factors are being actively explored. The recent emergence of highly effective direct‐acting antivirals (DAA) for hepatitis C virus (HCV) has shifted the focus of research interest to outcomes after viral eradication. Ever‐expanding inventories of molecular targeted agents and genomics technologies have enabled exploration of more personalized/stratified management of the patients. Here, we provide an overview of evolving challenges in HCC in relation to the changing landscape.

NAFLD/NASH as a Rising HCC Risk Factor

Recent epidemiological data consistently indicate that NAFLD/NASH associated with metabolic syndrome and obesity is a growing etiology of HCC.2 One of the surprising findings is that NAFLD/NASH‐related HCC frequently develops in the absence of cirrhosis (23%‐65%), contrary to the assumption that advanced fibrosis plays the major role in carcinogenesis as in HCV‐related HCC.3 NASH is also the most rapidly increasing indication of liver transplantation for HCC in the United States.4 However, risk factors of HCC development and molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis are still poorly understood, highlighting the urgent need for clinical and basic research on the pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH‐related HCC. Epidemiological, ideally prospective, studies should further clarify the magnitude of HCC risk in noncirrhotic NASH patients and identify noncirrhotic patients at higher risks for developing HCC who could benefit from HCC surveillance.5 However, the target population to enroll in such studies should be clarified. Screening of individuals based on metabolic parameters such as body mass index, diabetes, and dyslipidemia may be one way to enrich the target population, although future studies should validate this approach. However, such screening will require a close collaboration with endocrinologists, primary care physicians, paramedical staff, and social workers. Animal models faithfully mimicking the natural history of NAFLD/NASH‐related HCC development are expected to provide a mechanistic understanding for molecular drivers of carcinogenesis in noncirrhotic NAFLD/NASH patients, and to establish these drivers as biomarkers to refine HCC surveillance and/or targets for preventive interventions.

HCV‐related HCC in the DAA era

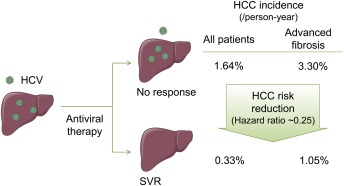

HCV is still the dominant HCC etiology in developed countries, accounting for 50%‐60% of newly diagnosed cases in the United States.2 The high efficacy of DAAs, reaching close to 100% sustained virological response (SVR) irrespective of the presence of cirrhosis and without serious toxicities, at least in the setting of clinical trials, holds great promise in eventually eradicating the infection.6 However, it will take time to make the drugs accessible to the HCV‐infected population due to their high costs.7, 8 A model‐based inference suggested that HCV‐related HCC will likely increase until 2030 despite improved SVR rates by DAAs.9 Moreover, the risk of HCC persists for decades even after achieving SVR, suggesting the necessity for continued regular HCC surveillance (Fig. 1).10, 11, 12 Several efforts have been made to develop risk predictors for HCV‐related HCC based on clinical and/or molecular variables.13 Future studies should evaluate their clinical utility before and after SVR. HCC risk predictors specific to post‐SVR patients in the DAA era may also have a value.

Figure 1.

Impact of HCV eradication on HCC incidence. HCC incidences in all HCV‐infected patients and patients with advanced fibrosis were obtained from Morgan et al,10 Aleman et al,11 and van der Meer.12 Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; SVR, sustained virological response. Some images were obtained from Servier Medical Art (www.servier.com).

HBV‐Related HCC

Although universal neonatal vaccination has successfully reduced HCC incidence by preventing new HBV infections,14 5% of the world population have already acquired chronic HBV infection and are at risk of HCC. Elevated serum levels of HBV DNA have been recurrently shown as a predictive factor of HCC occurrence and have been incorporated in several risk indices that are awaiting further clinical validation.15 Despite the described association between HBV DNA levels and HCC, current treatment guidelines do not recommend starting antiviral therapy solely based on elevated HBV DNA levels.16 Recently, provocative studies have shown that antiviral therapy can be efficacious in immune‐tolerant HBV patients with high HBV DNA but no signs of liver injury; however, further studies should clarify whether this subset of patients benefit from this treatment and whether their risk of HCC is reduced.17, 18 Given the successful clinical deployment of anti‐HCV drugs, the viral research community has now shifted its focus to the development of direct acting anti‐HBV drugs, aiming to cure chronic HBV infection by targeting HBV covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA).19 If successful, such antiviral therapies may have a role in secondary HCC prevention (ie, prevention of first HCC development) and/or tertiary prevention (prevention of subsequent HCC development after curative treatment of first HCC), which may have a substantial impact on the prognosis of the 240 million individuals worldwide who already acquired chronic HBV infection.20

Genomic Information for personalized/stratified/prioritized HCC Care

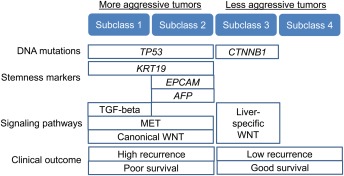

Despite the diverse HCC etiologies that are assumed to be linked to distinct mechanisms of carcinogenesis, the landscape of molecular alterations observed in fully developed HCC tumors are almost indistinguishable between the etiologies, suggesting a need to establish cross‐etiology molecular HCC classification.21 Genomic profiling studies in the past decade have clarified several molecular subclasses of HCC tumors (Fig. 2). This type of information may provide clues to the response to molecular targeted anticancer agents under development. Following the series of failed phase 3 trials in HCC based on the “all comer” approach, there is an increasing interest to incorporate molecular biomarkers of drug response in clinical trials to enroll only predicted responders to improve detection of therapeutic benefit.22 Some of the molecular subclasses have been recurrently associated with patient prognosis after certain locoregional therapies, mainly surgical resection, and may guide indication of the therapies if independently validated and implemented in clinically applicable assays.23, 24 Another interesting observation from the genomic/molecular studies is that existing tumor markers are tightly linked to specific molecular subclasses of HCC. For example, alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP) was found to be one of the hallmarks of an HCC subclass characterized by the positivity of stemness markers such as EPCAM, which could be molecularly targeted by a GPC3 antibody, or an AFP‐targeting cancer vaccine currently under preclinical or clinical evaluation.25, 26 The low positivity/sensitivity of AFP was shown to be a serious limitation for the use of AFP as a globally applicable tumor marker,27, 28 but these recent reports suggest that AFP and other existing tumor markers could instead be used as readily available indicators of the molecular subclasses and companion biomarkers for such molecular targeted therapies.29 This strategy could have a huge clinical impact, given the costly and lengthy process of new biomarker development.

Figure 2.

Molecular classification of HCC tumor. Abbreviations: AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; TGF‐β, transforming growth factor β.

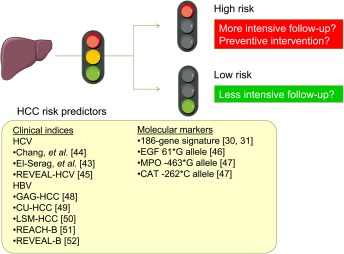

This approach, that uses molecular biomarker‐guided therapeutic intervention, could be extended to the development of HCC chemopreventive therapy based on molecular testing such as the HCC risk gene signature (Fig. 3).30, 31, 32, 33 Cancer chemoprevention trials have been highly resource‐intensive, requiring the enrollment of thousands of patients, a follow‐up time approaching decade(s), and rarely yielding positive results.34, 35 HCC risk biomarker‐based clinical trial enrichment will lower the barriers to conduct cancer chemoprevention trials by substantially reducing required sample size and the duration of follow‐up.13 Also, such biomarkers may guide personalized HCC surveillance to enable more cost‐effective early HCC detection.30

Figure 3.

HCC risk predictor‐based personalized/stratified patient management. Abbreviations: CU‐HCC, Chinese University‐HCC score; GAG‐HCC: Guide with Age, Gender, HBV DNA, Core promoter mutations and Cirrhosis, HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; REACH‐B, Risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B; REVEAL‐B/REVEAL‐HCV, Risk Evaluation of Viral Load Elevation and Associated Liver Disease/Cancer in HBV/HCV. Some images were obtained from Servier Medical Art (www.servier.com).

There has been a trend toward less‐invasive imaging and serum marker‐based diagnosis and management of HCC, which resulted in no requirement for tissue‐based diagnosis in unequivocal cases in routine clinical care.36 As a consequence, surgically resected tissues have been the only available source of molecular information, and therefore the findings are not always readily applicable outside the surgical context. However, given the recent active development of highly selective molecular targeted agents, it is increasingly recognized that tissue‐based molecular analysis provides clinically actionable information that guides therapeutic decisions as demonstrated in other cancer types.37 In HCC, recent practice guidelines now mandate tissue acquisition at least in the setting of research and clinical trials.38, 39 If future studies successfully demonstrate the clinical utility of tissue‐based biomarkers, it will be justifiable to revive tissue biopsy for the development and implementation of “precision medicine”40 in HCC. Body fluid–based measurement of circulating molecular markers such as microRNA, circulating tumor DNA, and circulating tumor cell may be a future option to acquire equivalent molecular information less invasively, although tissue will still be required during the phase of biomarker discovery, assay development, and clinical evaluation.41, 42

In summary, we are now experiencing a changing landscape of HCC etiologies, and facing rapid development of molecular information‐based diagnostic and therapeutic technologies that may enable personalized care of our patients. The recent epidemic of NAFLD/NASH has highlighted the necessity to delineate distinct risk factors and mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. The emergence of highly effective antiviral therapies in HCV may lead to their use as potential HCC preventive measures, although HCC risk predictors after achieving viral clearance should also be explored. HCC risk biomarkers will play a central role in the conduct of HCC chemoprevention clinical trials as well as personalized/stratified and more cost‐effective HCC surveillance. The acquisition of tissue specimens will greatly facilitate discovery and clinical translation of new molecular biomarkers and molecular targeted therapies that will eventually enable personalized “precision medicine” to significantly improve the dismal prognosis of HCC.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. El‐Serag HB, Kanwal F. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: Where are we? Where do we go? Hepatology 2014;60:1767–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Michelotti GA, Machado MV, Diehl AM. NAFLD, NASH and liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:656–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wong RJ, Cheung R, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology 2014;59:2188–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oda K, Uto H, Mawatari S, Ido A. Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review of human studies. Clin J Gastroenterol 2015;8:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feeney ER, Chung RT. Antiviral treatment of hepatitis C. BMJ 2014;348:g3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thomas DL. Global control of hepatitis C: where challenge meets opportunity. Nat Med 2013;19:850–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chung RT, Baumert TF. Curing chronic hepatitis C — The arc of a medical triumph. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1576–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harris RJ, Thomas B, Griffiths J, Costella A, Chapman R, Ramsay M, et al. Increased uptake and new therapies are needed to avert rising hepatitis C‐related end stage liver disease in England: Modelling the predicted impact of treatment under different scenarios. J Hepatol 2014;61:530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck‐Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta‐analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aleman S, Rahbin N, Weiland O, Davidsdottir L, Hedenstierna M, Rose N, et al. A risk for hepatocellular carcinoma persists long‐term after sustained virologic response in patients with hepatitis C‐associated liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all‐cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA 2012;308:2584–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoshida Y, Fuchs BC, Bardeesy N, Baumert TF, Chung RT. Pathogenesis and prevention of hepatitis C virus‐induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2014;61:S79–S90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chiang C, Yang Y, You S, Lai M, Chen C. Thirty‐year outcomes of the national hepatitis B immunization program in taiwan. JAMA 2013;310:974–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang HI, Lee MH, Liu J, Chen CJ. Risk calculators for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients affected with chronic hepatitis B in Asia. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:6244–6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen C, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, et al; REVEAL‐HBV Study Group . Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 2006;295:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan HL, Chan CK, Hui AJ, Chan S, Poordad F, Chang TT, et al. Effects of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in hepatitis B e antigen‐positive patients with normal levels of alanine aminotransferase and high levels of hepatitis B virus DNA. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1240–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tseng TC, Kao JH. Treating immune‐tolerant hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat 2015;22:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, Zhang K, Stadler D, Cheng X, et al. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science 2014;343:1221–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoshida Y, Fuchs BC, Tanabe KK. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma: potential targets, experimental models, and clinical challenges. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2012;12:1129–1159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Totoki Y, Tatsuno K, Covington KR, Ueda H, Creighton CJ, Kato M, et al. Trans‐ancestry mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma genomes. Nat Genet 2014;46:1267–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Llovet JM. Liver cancer: time to evolve trial design after everolimus failure. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014;11:506–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoshida Y, Nijman SM, Kobayashi M, Chan JA, Brunet JP, Chiang DY, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2009;69:7385–7392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nault JC, De Reynies A, Villanueva A, Calderaro J, Rebouissou S, Couchy G, et al. A hepatocellular carcinoma 5‐gene score associated with survival of patients after liver resection. Gastroenterology 2013;145:176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hong Y, Peng Y, Guo ZS, Guevara‐Patino J, Pang J, Butterfield LH, et al. Epitope‐optimized alpha‐fetoprotein genetic vaccines prevent carcinogen‐induced murine autochthonous hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2014;59:1448–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhu AX, Gold PJ, El‐Khoueiry AB, Abrams TA, Morikawa H, Ohishi N, et al. First‐in‐man phase I study of GC33, a novel recombinant humanized antibody against glypican‐3, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giannini EG, Marenco S, Borgonovo G, Savarino V, Farinati F, Del Poggio P, et al. Alpha‐fetoprotein has no prognostic role in small hepatocellular carcinoma identified during surveillance in compensated cirrhosis. Hepatology 2012;56:1371–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marrero JA, Feng Z, Wang Y, Nguyen MH, Befeler AS, Roberts LR, et al. Alpha‐fetoprotein, des‐gamma carboxyprothrombin, and lectin‐bound alpha‐fetoprotein in early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2009;137:110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deshmukh M, Hoshida Y. Genomic profiling of cell lines for personalized targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013;58:2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Sangiovanni A, Sole M, Hur C, Andersson KL, et al. Prognostic gene expression signature for patients with hepatitis C‐related early‐stage cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1024–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. King LY, Canasto‐Chibuque C, Johnson KB, Yip S, Chen X, Kojima K, et al. A genomic and clinical prognostic index for hepatitis C‐related early‐stage cirrhosis that predicts clinical deterioration. Gut 2014; doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-0000-0000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Kobayashi M, Peix J, Chiang DY, Camargo A, et al. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1995–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fuchs BC, Hoshida Y, Fujii T, Wei L, Yamada S, Lauwers GY, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition attenuates liver fibrosis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2014;59:1577–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 2009;301:39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Di Bisceglie AM, Shiffman ML, Everson GT, Lindsay KL, Everhart JE, Wright EC, et al. Prolonged therapy of advanced chronic hepatitis C with low‐dose peginterferon. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2429–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garraway LA. Genomics‐driven oncology: framework for an emerging paradigm. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1806–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. EASL‐EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Torbenson M, Schirmacher P. Liver cancer biopsy – back to the future?! Hepatology 2015;61:431–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 2015;372:793–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schwarzenbach H, Nishida N, Calin GA, Pantel K. Clinical relevance of circulating cell‐free microRNAs in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014;11:145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wong KF, Xu Z, Chen J, Lee NP, Luk JM. Circulating markers for prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Opin Med Diagn 2013;7:319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. HB El-Serag, F Kanwal, JA Davila, J Kramer, P Richardson. A New Laboratory-Based Algorithm to Predict Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Hepatitis C and Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1249–1255.e1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. KC Chang, YY Wu, CH Hung, SN Lu, CM Lee, KW Chiu, MC Tsai, et al. Clinical-guide risk prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma development in chronic hepatitis C patients after interferon-based therapy. British journal of cancer 2013;109:2481–2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. MH Lee, SN Lu, Y Yuan, HI Yang, CL Jen, SL You, LY Wang, et al. Development and validation of a clinical scoring system for predicting risk of HCC in asymptomatic individuals seropositive for anti-HCV antibodies. PLoS One 2014;9:e94760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. BK Abu Dayyeh, M Yang, BC Fuchs, DL Karl, S Yamada, JJ Sninsky, TR O'Brien, et al. A functional polymorphism in the epidermal growth factor gene is associated with risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2011;141:141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. P Nahon, J Zucman-Rossi. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2012;57:663–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. M‐F Yuen, Y Tanaka, DY‐T Fong, J Fung, DK‐H Wong, JC‐H Yuen, DY‐K But, et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. Journal of hepatology 2009;50:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. VW‐S Wong, SL Chan, F Mo, T‐C Chan, HH‐F Loong, GL‐H Wong, YY‐N Lui, et al. Clinical Scoring System to Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B Carriers. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010;28:1660–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. GL‐H Wong, HL‐Y Chan, CK‐Y Wong, C Leung, CY Chan, PP‐L Ho, VC‐Y Chung, et al. Liver stiffness-based optimization of hepatocellular carcinoma risk score in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Journal of Hepatology 2014;60:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. H‐I Yang, M‐F Yuen, HL‐Y Chan, K‐H Han, P‐J Chen, D‐Y Kim, S‐H Ahn, et al. Risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B (REACH-B): development and validation of a predictive score. The Lancet Oncology 2011;12:568–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. M‐H Lee, H‐I Yang, J Liu, R Batrla‐Utermann, C‐L Jen, UH Iloeje, S‐N Lu, et al. Prediction models of long-term Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma risk in chronic hepatitis B patients: Risk scores integrating host and virus profiles. Hepatology 2013;58:546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]