Abstract

This article provides an overview of some common challenges and opportunities related to cultural adaptation of behavioral interventions. Cultural adaptation is presented as a necessary action to ponder when considering the adoption of an evidence-based intervention with ethnic and other minority groups. It proposes a roadmap to choose existing interventions and a specific approach to evaluate prevention and treatment interventions for cultural relevancy. An approach to conducting cultural adaptations is proposed, followed by an outline of a cultural adaptation protocol. A case study is presented, and lessons learned are shared as well as recommendations for culturally grounded social work practice.

Keywords: evidence-based practice, literature

Culture influences the way in which individuals see themselves and their environment at every level of the ecological system (Greene & Lee, 2002). Cultural groups are living organisms with members exhibiting different levels of identification with their common culture and are impacted by other intersecting identities. Because culture is fluid and ever changing, the process of cultural adaptation is complex and dynamic. Social work and other helping professions have attempted over time to integrate culture of origin into the interventions applied with ethnic minorities and other vulnerable communities in the United States and globally (Sue, Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992). In an ever-changing cultural landscape, there is a renewed need to examine social work education and the interventions social workers implement with cultural diverse communities.

Culturally competent social work practice is well established in the profession and it is rooted in core social work practice principles (i.e., client centered and strengths based). It strives to work within a client’s cultural context to address risks and protective factors. Cultural competency is a social work ethical mandate and has the potential for increasing the effectiveness of interventions by integrating the clients’ unique cultural assets (Jani, Ortiz, & Aranda, 2008). Culturally competent or culturally grounded social work incorporates culturally based values, norms, and diverse ways of knowing (Kumpfer, Alvarado, Smith, & Bellamy, 2002; Morano & Bravo, 2002).

Despite the awareness about the importance of implementing culturally competent approaches, practitioners often struggle with how to integrate the client’s worldview and the application of evidence-based practices (EBPs). When selecting and implementing social work interventions, practitioners often continue to unconsciously place themselves at the center of the provider–consumer relationship. Being unaware of their power in the relationship and undervaluing the clients perspective in the selection of EBPs tends to result in a type of social work practice that is culturally incompetent and nonefficacious (Kirmayer, 2012). This ineffectiveness can be experienced and interpreted by practitioners in several ways. In instances when clients do not conform to the content and format of existing interventions, they are easily labeled as being resistant to treatment (Lee, 2010). In other cases, when clients fail to adapt to a given intervention that does not feel comfortable to them, the relationship is terminated or the client simply does not return to services. Thus, terms such as noncompliance and nonadherence may hide deeper issues related to cultural mismatch or a lack of cultural competency in the part of the practitioner.

Culturally grounded social work challenges practitioners to see themselves as the other and to recognize that the responsibility of cultural adaptation resides not solely on the clients but involves everyone in the relationship (Marsiglia & Kulis, 2009). In order to do this, practitioners need to have access to interventions or tools that are consistent with the culturally grounded approach. A culturally grounded approach starts with assessing the appropriateness of existing evidence-based interventions and adapting when necessary, so that they are more relevant and engaging to clients from diverse cultural backgrounds, without compromising their effectiveness. This process of assessment, refinement, and adaptation of interventions will lead to a more equitable and productive helping relationship.

The ecological systems approach provides a structure for understanding the importance of cultural adaptation in social work practice. Situated on the outer level (macro level) of the ecological system, culture frames the norms, values, and behaviors that operate on every other level: individual beliefs and behaviors (micro level), family customs and communication patterns (mezzo level), and how that individual perceives and interacts with the larger structures (exo level), such as the school system or local law enforcement (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). In this approach, the relationships between individuals, institutions, and the larger cultural context within the ecological framework are bidirectional, creating a dynamic and rapidly evolving system (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Gitterman, 2009). The bidirectional nature of relationships is an important concept to consider when discussing the cultural adaptation of social work interventions for two reasons: (1) regardless of the setting, in social work practice, the clients and the social workers engage in work partnerships in which both parties must adapt to achieve a point of mutual understanding and communication and (2) culture is in constant flux, as individuals interact with actors and institutions which either maintain or shift cultural norms and values over time.

Although culturally tailoring prevention and treatment approaches to fit every individual may not be feasible, culturally grounded social work may require the adaptation of existing interventions when necessary while maintaining the fidelity or scientific merit of the original evidence-based intervention (Sanders, 2000). This article discusses the need for cultural adaptation, presents a model of adaptation from an ecological perspective, and reviews the adaptations conducted by the Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center (SICR) as a case study. The recommendations section connects the premises of this article with the existing literature on cultural adaptation and identifies some specific unresolved challenges that need to be addressed in future research.

Empirically Supported Interventions (ESIs) in Social Work Practice

EBP has become the gold standard in social work practice and involve the “conscientious” and “judicious” application of the best research available in practice (Sackett, 1997, p. 2). It is commonly believed that utilizing EBP simply requires the practitioner to locate interventions that have been rigorously tested using scientific methods, implement them, and evaluate their effect; however, EBP acknowledges the role of individuals and relationships in this process. EBP requires the integration of evidence and scientific methods with practice wisdom, the worldview of the practitioner, and the client’s perspectives and values (Howard, McMillen, & Pollio, 2003; Regehr, Stern, & Shlonsky, 2007). The clinician’s judgment and the client’s perspective are not only utilized in the selection of the EBP intervention; they are also influential in how the intervention is applied within the context of the clinical interaction (Straus & McAlister, 2000). Achieving a balance between both the client and the practitioner’s perspective in the application of ESIs is essential for bridging the gap between research and practice (Howard et al., 2003). However, the inclusion of the clinician’s judgment and the client’s history potentially muddles the scientific merit of the intervention being implemented. This is the fundamental tension and challenge when implementing EBP and a key reason why the gap between research and practice exists (Regehr et al., 2007).

The attraction of EBP is clear; locating and potentially utilizing empirically tested treatment and prevention interventions allow social workers to feel more confident that they will achieve the desired outcomes and provide clients with the best possible treatment, thereby fulfilling their ethical responsibility (Gilgun, 2005). Despite this clear rationale, the utilization of EBP is limited (Mullen & Bacon, 2006) and when it is applied, research-supported interventions may not be implemented in the manner the authors of the intervention intended.

This lack of treatment fidelity when implementing EBP may be due to practitioner’s awareness that the evidence generated by randomized control trials (RCTs) may not be applicable to the diverse needs of their clients or adequately address the complexity of the clients’ life (Webb, 2001; Witkin, 1998). Practitioners have natural tendency to adapt interventions to better fit their clients (Kumpfer et al., 2002). Some adaptations are made consciously, but others are made quickly during the course of implementation and based on clinical judgment (Bridge, Massie, & Mills, 2008; Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004). ESIs, however, can only be expected to achieve the same results as those observed when originally tested, if they are implemented with fidelity or strict adherence to the program structure, content, and dosage (Dumas, Lynch, Laughlin, Phillips Smith, & Prinz, 2001; Solomon, Card, & Malow, 2006). Although adaptations are typically made in response to a perceived need, when they are not done systematically, based on evidence and with the core elements of the intervention preserved, the efficacy that was previously achieved in the more controlled environment may not be replicated (Kumpfer et al., 2002). Informal adaptation has the potential for compromising the integrity of the original intervention, thus negating the value of the accumulated evidence that supports the intervention’s effectiveness. This tension between fidelity and fit has generated a need for strategies to create fit while insuring fidelity.

Cultural Adaptation

The primacy of scientific rigor over cultural congruence may be a limitation in applying ESIs and a standard that should not be maintained in culturally competent social work practice. When working with real communities, both must be satisfied to the highest degree possible (Regehr et al., 2007). One solution to tension between using culturally relevant practices and ESIs is locating interventions that have been designed for and tested with a given cultural group. However, the limited availability of culturally specific interventions with strong empirical support may create barriers to this approach. Despite the progress that has been made to date, most ESIs are developed for and tested with middle-class White Americans, with the assumption that evidence of efficacy with this group can be transferred to nonmajority cultures, which may or may not be the case (Kumpfer et al., 2002).

For example, a prevention intervention with Latino parents found that assimilated, highly educated Latino parents were responsive to the prevention interventions presented to them, while immigrant parents with less education were less likely to benefit (Dumka, Lopez, & Jacobs-Carter, 2002). This highlights the differential effects of an intervention based on culture as well as a clear need for a more culturally relevant intervention for immigrant parents. Despite a clear need for adaptation in some circumstances, there is a strong risk of compromising the effectiveness of the ESI when unstructured cultural adaptations are implemented in response to perceived cultural incongruence (Kirk & Reid, 2002; Kumpfer & Kaftarian, 2000; Miller, Wilbourne, & Hettema, 2003; Solomon et al., 2006). For that reason, when culturally and contextually specific interventions exist with strong evidence, it is certainly preferable to select that intervention; however, in the absence of an ESI designed and tested for the population being served, adaptation may be a more viable and cost-effective option for scientifically merging a client’s cultural perspectives/values and the ESI (Howard et al., 2003; Steiker et al., 2008). Systematically adapting an intervention may increase the odds that the treatment will achieve similar results than those found in more controlled environments by minimizing the amount of spontaneous adaptations that the practitioner feels that they must make to communicate within the client cultural frame (Ferrer-Wreder, Sundell, & Mansoory, 2012).

Cultural adaptation may not only preserve the ESI’s efficacy but also enhance the results attained in clinical trials (Kelly et al., 2000). Culturally adapted interventions have the potential to improve both client engagement in treatment and outcomes and might be indicated when either rates fall below what could be expected based on previous evidence (Lau, 2006). In an evaluation of a culturally adapted version of the Strengthening Families intervention, there was a 40% increase in program retention in the culturally adapted version of the intervention (Kumpfer et al., 2002). Although outcomes were not found to be significantly better in the adapted version of the intervention, the increase in retention is a significant improvement. Improving retention expands the intervention’s potential to reach and impact individuals who would not typically remain in treatment. Despite the lack of difference in outcomes in the Strengthening Families intervention, some evidence has emerged that culturally adapted interventions not only increase retention but are also more effective. In a recent meta-analysis, culturally adapted treatments had a greater impact than standard treatments, produced better outcomes, and were most successful when they were culturally tailored to a single ethnic minority group (Smith, Domenech Rodríguez, & Bernal, 2010).

Adapting interventions in partnership with communities also enhances the community’s commitment to the implementation and the chances that the program will be sustained overtime (Castro et al., 2004). For example, efforts to adapt HIV prevention programs by modifying the messages and protocols in order for them to sound and feel natural or familiar intellectually and emotionally to individuals, families, groups, and communities have improved the communities’ receptiveness, retention, outcomes, and overall satisfaction, in addition to retaining high levels of fidelity (Kirby, 2002; Raj, Amaro, & Reed, 2001; Wilson & Miller, 2003).

Finally, cultural adaptation is advantageous because it allows the social worker to address culturally specific risk factors and build on identified protective factors. In the case of Latino families, differential rates of acculturation between parents and youth appear to be a risk factor for substance use and delinquency among youth, indicating that family-based interventions may be the most culturally relevant intervention (Martinez, 2006). In addition to a source of risk, cultural norms that place a high value on family loyalty are protective factors against a variety of negative outcomes (German, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2009; Marsiglia, Nagoshi, Parsai, & Castro, 2012). Identifying risk and protective factors unique to a community and addressing these within an intervention have the potential to increase the efficacy of the intervention.

The importance of EBP and culturally competent practice has created tension in the field of social work. Evidence has landed support to both claims: (1) interventions are more effective when implemented with fidelity (Durlak & DuPre, 2008) and (2) interventions are more effective when they are culturally adapted because they ensure a good fit (Jani et al., 2008). These different perspectives highlight the tension in the field between implementing manualized interventions exactly as they were written versus to adjusting them to fit the targeted population or community (Norcross, Beutler, & Levant, 2006). Although this debate is far from resolved, theories of adaptation have been developed that allow the researcher/practitioner to adjust the fit without compromising the integrity of the intervention (Ferrer-Wreder et al., 2012). If the cultural adaptation is done systematically, it has the potential for maximizing the benefit of the fit, as well as the benefit of the ESI, thus providing a strategy that addresses many of the concerns surrounding EBP’s applicability in social work practice (Castro et al., 2004).

AnEmerging Roadmap for Cultural Adaptation

Cultural adaptation is an emerging science that aims at addressing these challenges and opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of interventions by grounding them in the lived experience of the participants. Strategies and processes to systematically adapt interventions while insuring a more optimal cultural fit without compromising the integrity of scientific merit have been proposed and are beginning to be tested (La Roche & Christopher, 2009). The first step in all adaptation models is determining that the cultural adaptation of an intervention should be perused. Adaptation of an ESI is indicated when (1) a client’s engagement in services falls below what is expected, (2) expected outcomes are not achieved, and (3) identified culturally specific risks and/or protective factors need to be incorporated into the intervention (Barrera & Castro, 2006).

Once the determination is made to conduct an adaptation, there are a variety of models that one could follow all of which fall into two categories: content and process (Ferrer-Wreder et al., 2012). Although most current adaptation models have merged the discussions regarding the content that should be modified and process by which this modification takes place, it is useful to consider them separately.

Content models identify an array of domains that may be crucial to address when conducting an adaptation. The ecological validity model, for example, focuses on eight dimensions of culture: language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and social context (Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey, & Domenech Rodríguez, 2009). The cultural sensitivity model, also a content model, identifies two distinct content areas: deep culture, which includes aspects of culture such as thought patterns, value systems, and norms, and surface culture, which refers to elements, such as language, food, and customs (Resnicow, Soler, Braithwaite, Ahluwailia, & Butler, 2000). Proponents of the cultural sensitivity model argue that both aspects of culture should be assessed and potentially addressed if areas of conflict or incongruence between the culture and the intervention are identified (Resnicow et al., 2000). Surface adaptations allow the participants to identify with the messages, potentially enhancing engagement; while, deep culture adaptations ensure that the outcomes are impacted (Resnicow et al., 2000).

Castro, Barrera, and Martinez (2004) and Castro, Barrera, and Steiker, 2010 have proposed a content model that identifies a set of specific dimensions—at the surface and deep levels— that are essential to consider in the adaptation process: cognitive, affective, and environmental. Cognitive adaptations are considered when participants cannot understand the content that is being presented due to language barriers or the use of information that is not relevant in an individual’s cultural frame. Vignettes given by the original intervention, for example, may not be relevant to the participants or may be offensive due to spiritual or religious taboos. The content may create a negative reaction from the participants which in turn may block their ability to hear and integrate the message. It is that content that needs to be modified while the core elements of the intervention are respected. Affective-motivational adaptations are indicated when program messages are contrary to cultural norms and values, creating a resistance to change within the individual (Castro, Rawson, & Obert, 2001). Environmental factors (later referred to as relevance) make sure that the contents and structure are applicable to the participants in their daily lived experience (Castro et al., 2010).

While content models of adaptation tell adaptors where to look for cultural mismatch, process models provide a framework for making systematic assessments of cultural match, adjustments to the original intervention, and tests of the adaptations effectiveness. At a minimum adaption process, models follow two systematic steps: (1) identifying mismatches between the original intervention and the client’s culture and (2) testing/evaluating changes that have been made to rectify these disparities (Ferrer-Wreder et al., 2012).

Most process models of adaptation begin with building a partnership or coalition with members of targeted community (Castro et al., 2010; Harris et al., 2001; Wingood & DiClemente, 2008). Sometimes the ESI that will be adapted is selected at this stage; however, more information is often gathered about the targeted population before selecting the intervention that would provide the best fit (Kumpfer, Pinyuchon, Teixeriade de Melo, & Whiteside, 2008; Mckleroy et al., 2006; Wingood & DiClemente, 2008). Whether the intervention has yet to be selected, extensive formative research is conducted to assess the etiology of the social problem that is the target of the intervention, possible population-specific risks and protective factors, and measurement equivalence to insure and accurate evaluation of intervention outcomes (Harris et al., 2001). Some information about the target community may be gained by reviewing relevant literature; however, interviews, focus groups, and surveys are also used to collect primary data about the social and cultural context that may impact the outcome of the intervention or conflict with the program’s messages/ implementation strategies.

At this point in the process, some adaptation models recommend making changes based on the formative research (Domenech-Rodriguez&Wieling, 2004; Harris et al., 2001),while others suggest implementing the intervention with minimal changes and assessing the need for further adaption. In an innovative approach, the Planned InterventionAdaptationmodel suggests making significant changes to one version of the intervention while making minimal changes to another and implementing them both simultaneously to test the differential effects (Castro et al., 2010; Ferrer-Wreder et al., 2012; Kumpfer et al., 2008).

Regardless of the level of adaptation, the modified intervention is pilot tested and based on the outcomes subsequent adaptations are made (Ferrer-Wreder et al., 2012). Once a final adaptation has been made, further testing takes place in effectiveness trials. Across all theories of adaptation, the process is iterative with refinements made to the intervention at every stage based on the evidence generated in the prior stage (Domenech-Rodriguez & Wieling, 2004). Regardless of the depth of changes made, the adapted intervention must be rigorously tested to ensure that the effects of the original ESI are preserved after changes have been made.

Case Study: Adaptations of Keepin’it REAL (KiR), the Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center (SIRC) Approach

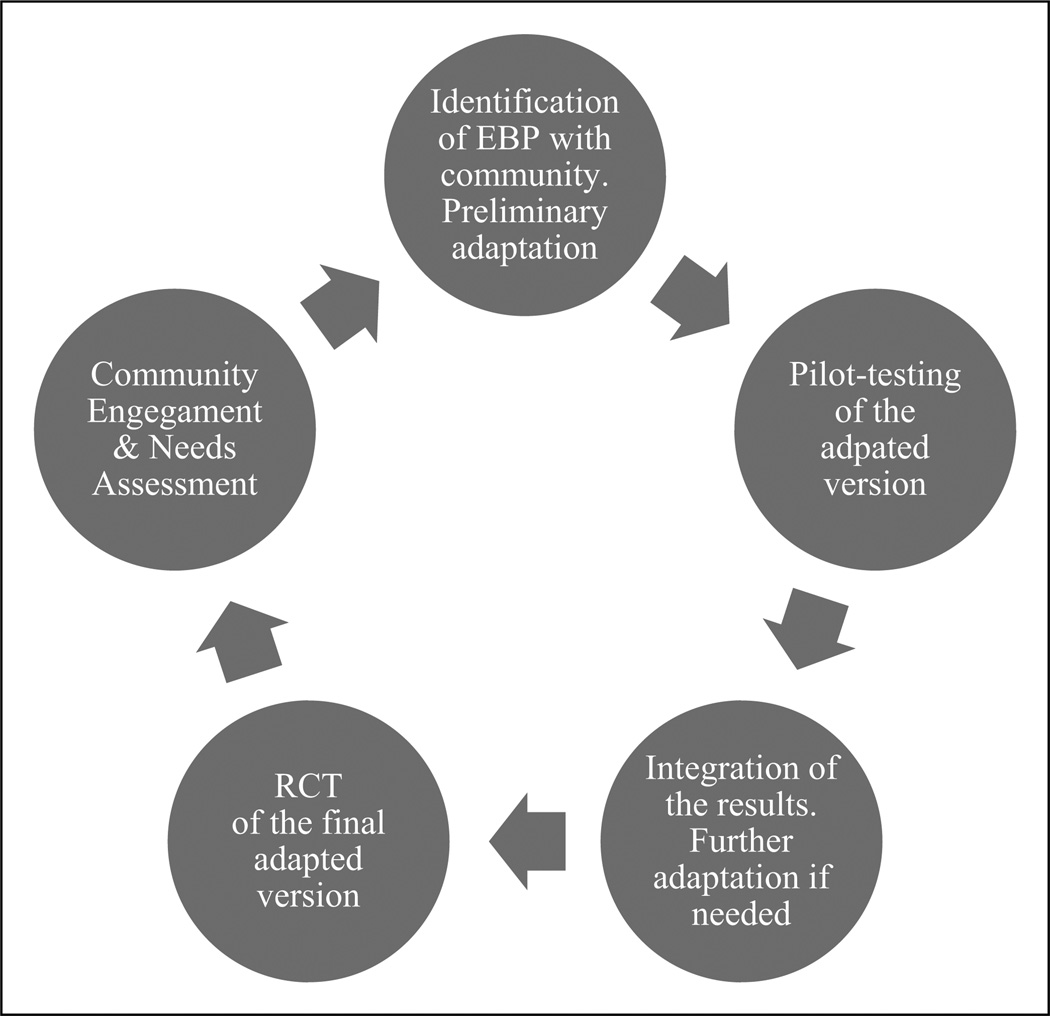

Over the past 10 years of health disparities research, the SIRC has developed a process of cultural adaptation that includes most of the elements outlined previously. The specific adaptation model utilized at SIRC is an expanded version of the Barrera and Castro (2006) model as illustrated by Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The SIRC adaptation model (Barrera & Castro, 2006). Note. SIRC = Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Centre.

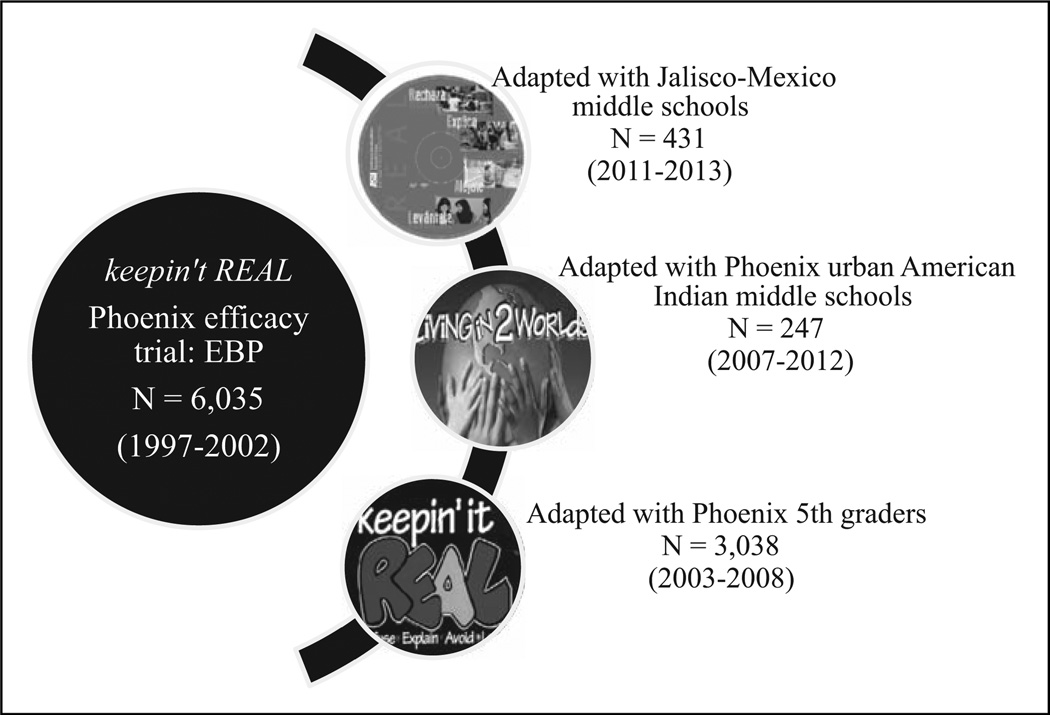

KiR is the flagship empirically supported treatment SIRC (Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005). KiR is a manualized school-based substance abuse prevention program for middle school students. It was designed to (a) increase drug resistance skills among middle school students, (b) promote antisubstance use norms and attitudes, and (c) develop effective drug resistance and communication skills (Gosin, Dustman, Drapeau, & Harthun, 2003). It was created and evaluated in Arizona through many years of community-based research funded by the National Institutes on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. It is a model program listed under Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices. There is strong evidence about the efficacy of the intervention with middle school Mexican American students (Marsiglia, Kulis, Wagstaff, Elek, & Dran, 2005), however the communityidentified need to reach out to younger students and to students of other ethnic groups generated a set of adaptation efforts summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The SIRC family of adapted interventions. Note. SIRC = Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Centre.

As Figure 2 illustrates, KiR was adapted for fifth-grade students (Harthun, Dustman, Reeves, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2009) following the SIRC adaptation model and an RCT was conducted to test whether the effects of the intervention increased by intervening earlier (fifth grade vs. seventh grade). Students who received the intervention in both the fifth and seventh grade were no different in their self-reported use of alcohol and other drugs than students who received the intervention only on the seventh grade (Marsiglia, Kulis, Yabiku, Nieri, & Coleman, 2011). This effort did no yield the expected results but provided evidence from a developmental perspective that starting earlier was not cost effective.

The second adaptation presented in Figure 2 was also community-generated and supported from the evidence gathered during the initial RCT of KiR. Urban American Indian (AI) youth were not benefiting from KiR as much as other children (Dixon et al., 2007). Following the principles of community-based participatory research, a steering group, including leaders from the local urban AI community and school district personnel in charge of AI programs, was formed to guide the adaptation process. In addition to engaging community members and setting up a structure to ensure a collaborative partnership, before beginning the adaptation process, formative information was collected by consulting the literature to identify culturally specific risks and protective factors and focus groups. Focus groups were conducted with both Native American adults and youth to explore culturally specific drug resistance strategies that were frequently applied by urban Native American youth (Kulis & Brown, 2011; Kulis, Dustman, Brown, & Martinez, 2013).

Based on this information, collected in conjunction with four Native American curriculum development experts, KiR was adapted, and while maintaining its core elements, the content and structure were changed to be more culturally relevant to Native American youth (Kulis et al., 2013). Changes to the curriculum included (1) new drug resistant strategies that were identified by the AI youth as being more culturally relevant to them, (2) lesson plans designed to teach strategies in a more culturally relevant way, (3) more comprehensive content focusing on ethnic identity (a protective factor identified in the literature), and (5) a narrative approach in teaching content (Kulis et al., 2013). In the initial pilot test of the intervention, results showed an increase in the use of REAL strategies indicating a promising effect. Based on pilot test feedback, the intervention has been further adapted and implemented on a larger scale through an RCT. The research team at SIRC is currently in the process of developing a parenting component to this intervention using the processes that were established in the development of the youth version.

Implementing and adapting KiR for the Mexican context is the most recent adaptations done at SIRC. Collaborators in Jalisco-Mexico identified Keepin’ it as an ESI suitable for Mexico. The initial review of the intervention resulted in a “surface” adaptation consisting mostly of translating the manuals from English to Spanish and changing some of the vignettes that were not appropriate for Mexico. The Jalisco team recruited two middle schools to participate in a pilot study of the initial adapted version of KiR. The schools were randomized to control and experimental conditions. Implementers (teachers) and student participants participated in the regular classroom-based intervention for 10 weeks and were also a part of a simultaneous intensive review process of the intervention through focus groups. The overall level of comfort and satisfaction with the intervention was high and the pre- and posttest survey results were also favorable. The main concern for teachers and students was the videos that illustrate the REAL resistance strategies. The original videos were dubbed into Spanish, but the story lines, the music, and even the clothing felt foreign to the youth in Jalisco. As a result, new scripts and new videos were produced by and for youth in Jalisco. This method of adaptation did not change the core elements of the original intervention but did address aspects of deep culture (Steiker et al., 2008). Because the youth wrote and acted in the videos, they were able to construct scenarios that accurately reflected their cultural norms and values.

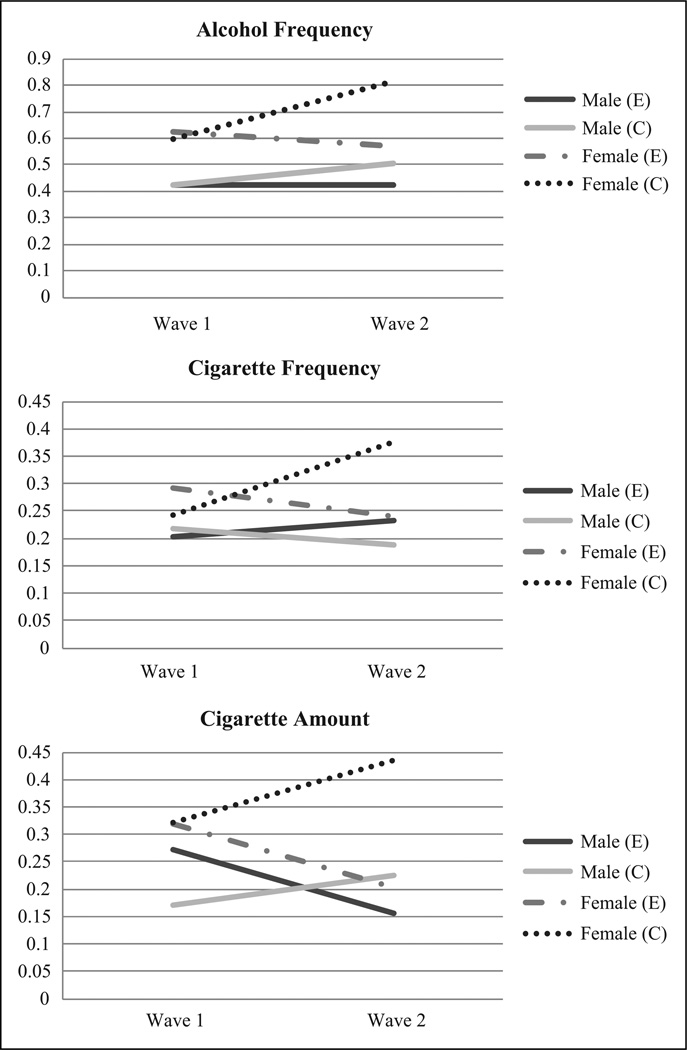

The results of the pilot also provided additional feedback to edit the content and format of the manuals. See Figure 3 for the pilot results on alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use.

Figure 3.

Pilot results of “Mantente REAL.”

The results of the pilot were very promising and identified female students at a greater risk. Females in the control group (not receiving the intervention) reported the greatest increase in substance use between the pre- and posttest. The pilot results illustrate the need for the cyclical and continuous adaptation process. This case study highlights the need to conduct a gender adaptation in addition to an ethnic or nation of origin adaptation. With the adapted manual and the new videos, the binational team of researchers is applying for funding to conduct an RCT in Mexico of the revised intervention now called “Mantente REAL.”

Adaptation in Social Work Practice

The previously discussed models, including the SIRC model, are based on collaborations between practitioners and researchers, where researchers take the lead in the formative assessments, adaptations, and evaluations of effectiveness. In many social work practice settings, this process might look different, although it is recommended that regardless of the setting, a partnership with the intervention designers is developed if significant modifications are going to be made to the original intervention. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has devised a set of practical guidelines for practitioners adopting an ESI and strongly discourages adaptors to change the deep structures of the intervention (McKleroy et al., 2006).

In the CDC model, as in the SIRC model, the adaptation process starts with the selection of an ESI that best matches the population and context (Solomon et al., 2006). The selection of an intervention is based on an initial assessment of the targeted population and an exploration of possible intervention variations (Ferrer-Wreder et al., 2012). Assessments of the population can be made through a review of the literature and by conducting interviews with key informants or focus groups with potential participants. The initial assessment of the population should go beyond potential participants’ ethnicities to include multiple and intersecting identities. Cultural adaptation frequently starts and stops with the identification of race, without examining how age, gender, sexual orientation, religion, acculturation, and geography shape culture. The lack of such identification information could potentially impact the participants’ experience with the intervention (Wilson & Miller, 2003). A thorough assessment includes consideration for both deep and surface culture, as well as population-specific risksand protective factors (Solomon et al., 2006). During this initial phase, social workers strive to find the best possible fit because the fewer modifications they make, the less likely the fidelity of the intervention will be compromised in the adaptation process.

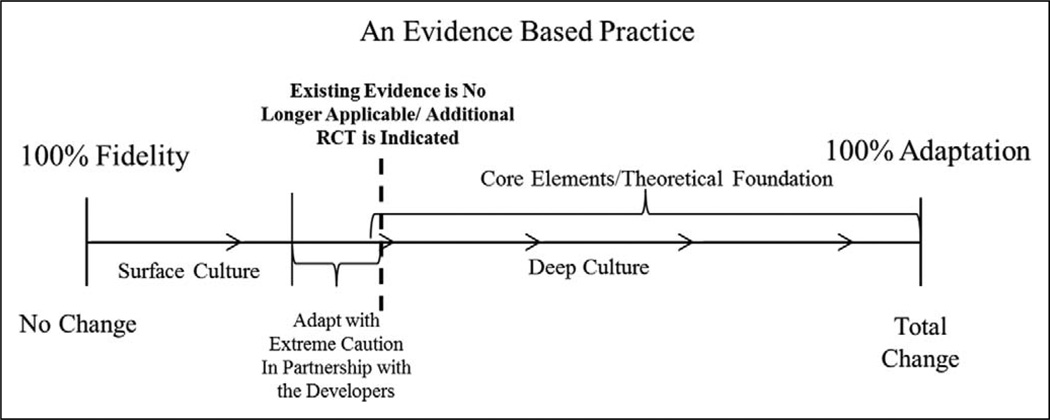

After the intervention is selected, the practitioner thoroughly evaluates the theoretical underpinnings of the intervention and assesses the intervention in light of the cultural norms and values of the clients being served (Green & Glasgow, 2006). The practitioner then systematically works to reconcile any mismatches between the intervention and the participants’ lived experiences without altering the core components of the intervention or features of the intervention that are responsible for the intervention’s effectiveness (Green & Glasgow, 2006; Kelly et al., 2000; Solomon et al., 2006). When it is determined that elements of deep culture need to be changed and these changes have the potential of altering core elements of the curriculum, the evidence previously found for effectiveness may be negated indicating the need to retest the intervention in an RCT (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The continuum of adaptation: Balancing the fidelity and fit.

Although some interventionists have explicitly identified core components that must be preserved to ensure effectiveness, others have not. In the case when they are not explicitly stated, it becomes the implementer’s responsibility to uncover aspects of the intervention that cannot be changed or removed. Identifying the theory of change (i.e., cognitive behavioral theory, reasoned action, and communication competency) is the most practical way of identifying core elements, although contacting the authors and conducting experiments are also possibilities (Solomon et al., 2006).

After the intervention has been adapted to reconcile any conflicting mismatches, a pilot test is recommended of the adapted intervention with a small group of participants (at least N = 10) using pre- or postsurveys and focus groups (McKleroy et al., 2006). Any information gleaned from this data will be used to further incorporate any adaptations into the intervention.

The extent of adaptation must be determined by the level of mismatch between the intervention and the population being served (Barrera & Castro, 2006). Frequently, cultural adaptations only address surface aspects of culture while neglecting the deeper messages being communicated in the intervention. This is not necessarily bad practice. It is possible that changing the language, photographs, and the scenarios in an intervention is all that is needed to make it culturally relevant. There are, however, situations in which this is not sufficient (Resnicow et al., 2000). As mentioned previously, surface adaptation allows participants in the program to identify themselves with the intervention, but it could fail to address the larger cultural norms that may be impacting the target behaviors or decision-making process. If it is determined that significant and/or deep changes are needed, the developers of the intervention need to be contacted and asked to assist the social worker in the process. It should be remembered that any changes have the potential to compromise the intervention’s effectiveness and need to be implemented with extreme caution. Social workers adapting interventions should document all changes made to the original intervention and systematically evaluate the outcomes in order to ensure that the desired results are being achieved.

Recommendations

Social work ethics clearly instruct social workers to provide culturally competent practice and to implement interventions with the best possible evidence of efficacy. Due to the vast diversity in the human family, these imperatives can be in conflict. This conflict highlights many of the questions that still linger in the discussion of the value of implementing social work interventions with fidelity versus adapting them to better achieve a cultural fit. It has been suggested that one way to rectify this tension is to adapt interventions in a systematic manner based on scientifically validated methods. Despite the apparent clarity of this task, the adaptation process can be challenging. The theories of adaptation that have emerged in several different fields put forward similar processes of adaptation. These may require an extensive assessment of the etiology of social problems, an understanding of the deep theoretical structure of the original intervention, and rigorous evaluation that may be beyond the capacity of individual practitioners. To this end, more work needs to be done to build the capacities of socialworkers and social work agencies for utilizing and conducting rigorous research that would enable them to reliably adapt social work research theories and practices. In the absence of needed resources, social workers are encouraged to build relationships with research institution that can help them systematically assess and adapt interventions, so that they can provide the most culturally competent services. When adaptations cannot be reliably implemented, efforts need to be made to identify interventions that have been previously adapted and tested with a given population, such as those in the SIRC model, and implement them with fidelity. With the ever expanding number of rigorously tested, culturally specific, and culturally grounded interventions, it may seem feasible at some point to have an ESI for every population in every context; however, the dynamic nature of culture and the vast diversity among humans ensure that cultural adaptation will continue to be a likely necessity in the future.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH Grant P20MD002316-05, to Flavio F. Marsiglia, principal investigator).

Footnotes

This article was previously presented at the conference on Bridging the Research and Practice gap: A Symposium on Critical Considerations, Successes and Emerging Ideas, sponsored by the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work, Houston, TX, April 5–6, 2013.

This article was invited and accepted by the Guest Editor of this special issue, Danielle Parrish, PhD The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMHD or the NIH.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Barrera M, Castro FG. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge TJ, Massie EG, Mills CS. Prioritizing cultural competence in the implementation of an evidence-based practice model. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:1111–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an environmental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 1977;32:513–531. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5:41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Steiker LKH. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Rawson R, Obert J. Cultural and treatment issues in the adaptation of the Matrix model for implementation in Mexico; Paper presented at the Centros de Integracion Juvenil Conference on Drug Abuse Treatment; Mexico City, Mexico. 2001. Dec 6–7, [Google Scholar]

- Dixon AL, Yabiku ST, Okamoto SK, Tann SS, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Burke AM. The efficacy of a multicultural prevention intervention among urban American Indian youth in the southwest US. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28:547–568. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0114-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech-Rodriguez M, Wieling E. Developing culturally appropriate, evidence-based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations. In: Rastogi M, Wieling E, editors. Voices of color: First person accounts of ethnic minority therapists. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Lynch AM, Laughlin JE, Phillips Smith E, Prinz RJ. Promoting intervention fidelity: Conceptual issues, methods, and preliminary results from the EARLY ALLIANCE prevention trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20:38–47. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Lopez VA, Jacobs-Carter S. Parenting interventions adapted for Latino families: Progress and prospects. In: Contreas JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CN: Praeger; 2002. pp. 203–231. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Wreder L, Sundell K, Mansoory S. Tinkering with perfection: Theory development in the intervention cultural adaptation field. Child and Youth Care Forum. 2012;41:149–171. [Google Scholar]

- German M, Gonzales NA, Dumka L. Familism values as a protective factor for Mexican-origin adolescents exposed to deviant peers. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:16–42. doi: 10.1177/0272431608324475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilgun JF. The four cornerstones of evidence-based practice in social work. Research on Social Work Practice. 2005;15:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gitterman A. The life model. In: Roberts AR, editor. Social worker’s desk reference. New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2009. pp. 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gosin MN, Dustman PA, Drapeau AE, Harthun ML. Participatory action research: Creating an effective prevention curriculum for adolescents in the Southwestern US. Health Education Research. 2003;18:363–379. doi: 10.1093/her/cyf026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Glasgow RE. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research issues in external validation and translation methodology. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2006;29:126–153. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene GJ, Lee MY. The social construction of empowerment. In: O’Melia & M, Milesy K, editors. Pathways to empowerment in social work practice. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2002. pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KJ, Ahluwalia JS, Okuyemi KS, Turner JR, Woods MN, Backinger CL, Resnicow K. Addressing culturalsensitivity in a smoking cessation intervention: Development of the kick it at Swope project. Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:447–458. [Google Scholar]

- Harthun ML, Dustman PA, Reeves LJ, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Using community-based participatory research to adapt keepin’it REAL: Creating a socially, developmentally, and academically appropriate prevention curriculum for 5th graders. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2009;53:12–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MO, McMillen CJ, Pollio DE. Teaching evidence-based practice: Toward a new paradigm for social work education. Research on Social Work Practice. 2003;13:234–259. [Google Scholar]

- Jani JS, Ortiz L, Aranda MP. Latino outcome studies in social work: A review of the literature. Research on Social Work Practice. 2008;19:179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Heckman TG, Stevenson LY, Williams PN, Ertl T, Hays RB, Neumann MS. Transfer of research-based HIV prevention interventions to community service providers: Fidelity and adaptation. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:87–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Effective approaches to reducing adolescent unprotected sex, pregnancy, and childbearing. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39:51–57. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk SA, Reid WJ. Science and social work: A critical appraisal. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health: Epistemic communities and the politics of pluralism. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Brown EF. Preferred drug resistance strategies of urban American Indian youth of the Southwest. Journal of Drug Education. 2011;41:203–234. doi: 10.2190/DE.41.2.e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Dustman P, Brown E, Martinez M. Expanding urban American Indian youths repertoire of drug resistance skills: Pilot Results from a culturally adapted prevention program. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2013;20:35–54. doi: 10.5820/aian.2001.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Smith P, Bellamy N. Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prevention Science. 2002;3:241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Kaftarian SJ. Bridging the gap between family-focused research and substance abuse prevention practice: Preface. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;21:169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M, Teixeriade de Melo A, Whiteside HO. Cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the Strengthening Families program. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2008;31:226–239. doi: 10.1177/0163278708315926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Roche MJ, Christopher MS. Changing paradigms from empirically supported treatment to evidence-based practice: A cultural perspective. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice; Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:396–402. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. Revisioning cultural competence in clinical social work practice. Families in Society. 2010;91:272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Keepin’it REAL: An evidence-based program. Santa Cruz, CA: ETR Associates; 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis SS. Diversity, oppression, and change: Culturally grounded social work. Chicago, IL: Lyceum Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Wagstaff DA, Elek E, Dran D. Acculturation status and substance use prevention with Mexican and Mexican-American youth. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5:85–111. doi: 10.1300/J160v5n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Yabiku S, Nieri T, Coleman E. When to intervene: Elementary school, middle school or both? Effects of keepin’it REAL on substance abuse trajectories of Mexican heritage youth. Prevention Science. 2011;12:48–62. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0189-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Nagoshi JL, Parsai M, Castro FG. The influence of linguistic acculturation and parental monitoring on the substance use of Mexican-heritage adolescents in predominantly Mexican enclaves of the Southwest US. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse. 2012;11:226–241. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2012.701566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR. Effects of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance use. Family Relations. 2006;55:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- McKleroy V, Galbraith J, Cummings B, Jones P, Gelaude D, Carey J. Adapting evidence based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Education Prevention. 2006;18:59–73. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL, Hettema JE. What works? A summary of alcohol treatment outcome research. Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches. 2003;3:13–63. [Google Scholar]

- Morano CL, Bravo M. A psychoeducational model for Hispanic Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:122–126. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen EJ, Bacon W. Implementation of practice guidelines and evidence-based treatment. In: Roberts AR, Yeager KR, editors. Foundations of evidence-based social work practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC, Beutler LE, Levant RF. Evidence-based practice in mental health: Debate and dialogue on the fundamental questions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Amaro H, Reed E. Culturally tailoring HIV/AIDS prevention programs: Why, when, and how. In: Kazarian S, Evans D, editors. Handbook of cultural health psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 195–239. [Google Scholar]

- Regehr C, Stern S, Shlonsky A. Operationalizing evidence-based practice the development of an institute for evidence-based social work. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;17:408–416. [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwaite RL, Ahluwalia JS, Butler J. Cultural sensitivity in substance use prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine. Seminars in Perinatology. 1997;21:3–5. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(97)80013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR. Community-based parenting and family support interventions and the prevention of drug abuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:929–942. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Domenech, Rodríguez MM, Bernal G. Culture. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010;67:166–175. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, Card JJ, Malow RM. Adapting efficacious interventions advancing translational research in HIV prevention. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2006;29:162–194. doi: 10.1177/0163278706287344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiker LKH, Castro FG, Kumpfer K, Marsiglia FF, Coard S, Hopson LM. A dialogue regarding cultural adaptation of interventions. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2008;8:154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Straus SE, McAlister FA. Evidence-based medicine: A commentary on common criticisms. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2000;163:837–841. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Arredondo P, McDavis RJ. Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 1992;20:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz MD, Hartel CR, editors. Drug abuse: Origins & interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Webb SA. Some considerations on the validity of evidence-based practice in social work. British Journal of Social Work. 2001;31:57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, Miller RL. Examining strategies for culturally grounded HIV prevention: A review. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:184–202. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.3.184.23838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: A model for adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. Journal of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. 2008;47:S40–S46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin SL. The right to effective treatment and the effective treatment of rights: Rhetorical empiricism and the politics of research. Social Work. 1998;43:75–80. [Google Scholar]