Abstract

Acute SLE courses with antibody-secreting cells (ASC) surges whose origin, diversity, and contribution to serum autoantibodies remain unknown. Deep sequencing, autoantibody proteome and single-cell analysis demonstrated highly diversified ASC punctuated by VH4-34 clones that produce dominant serum autoantibodies. A fraction of ASC clones contained unmutated autoantibodies, a finding consistent with differentiation outside the germinal centers. A substantial ASC segment derived from a distinct subset of newly activated naïve cells of significant clonality that persist in the circulation for several months. Thus, selection of SLE autoreactivities occurred during polyclonal activation with prolonged recruitment of recently activated naïve B cells. These findings shed light into SLE pathogenesis, help explain the benefit of anti-B cell agents and facilitate the design of future therapies.

Introduction

Antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) represent the main effector B cells in protective responses and in pathogenic conditions that include autoimmunity, allergy and transplantation. ASCs are released in large numbers into the circulation during recall vaccine responses, which induce a transient 10- to 40-fold increase after immunization1. Single-cell studies have shown that those ASCs are vaccine-specific, oligoclonal and highly mutated, thereby suggesting a derivation from pre-existing memory cells2.

ASC population expansions of an even larger magnitude are typical of acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)3. SLE is a relapsing autoimmune disease characterized by high titers of serum autoantibodies some of which (anti-dsDNA and 9G4 antibodies encoded by the VH4-34 gene segment), fluctuate with disease activity4,5. Given the availability of autoantigens and the abundance of memory cells in SLE, increased numbers of ASCs coincident with disease flares might be expected to represent oligoclonal expansions of pre-existing memory cells specific for lupus antigens. However, the properties of ASCs and their contribution to serum autoantibodies during SLE flares, remain uncertain.

We addressed these questions through synchronized analysis of sorted B cells and ASCs from SLE patients experiencing disease-associated flares. Repertoire properties and population inter-relatedness were elucidated using Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and the autoantibody compartment was analyzed using serum proteomics and single-cell monoclonal antibodies. Our results demonstrate that circulating ASCs found during SLE flares were highly polyclonal and did not predominantly recognize the most prevalent lupus antigens. Yet, this polyclonal repertoire was punctuated by expansions of complex clones predominantly expressing disease-specific VH4-34-encoded autoantibodies. A distinct subset of activated naïve B cells was an important source of ASCs and serum autoantibodies during SLE flares. This subset expressed highly reactive germline-encoded autoantibodies and persisted in the circulating pool for prolonged periods of time together with their ASC progeny. These results shed light into the mechanisms of B cell hyperactivity in SLE and can be used to segment patients and guide therapeutic options.

Results

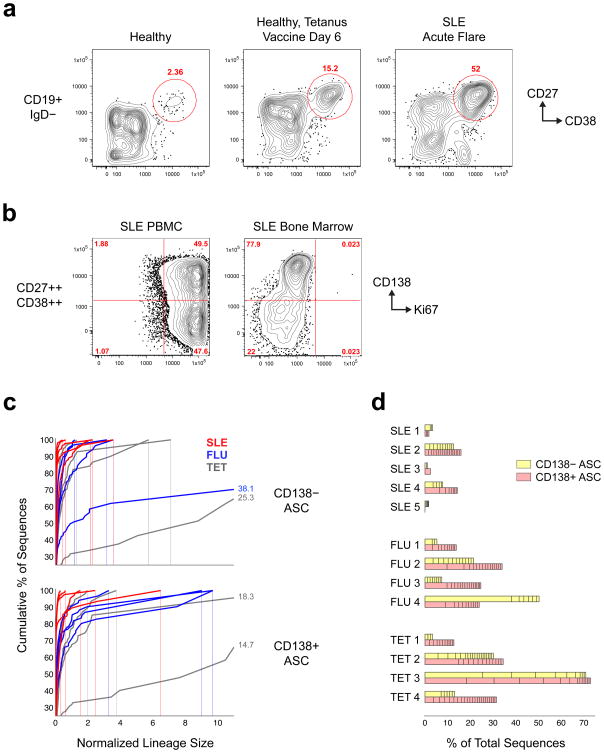

Polyclonality of circulating ASCs during SLE flares

Peripheral blood ASCs were obtained from SLE patients who were experiencing disease flares while on minimal immunosuppression (Supplementary Table 1). Consistent with previous observations3, ASCs defined as CD19+ IgD− CD27hi CD38hi were increased up to 40-fold (Fig. 1a) and included Ki67+CD138− and Ki67+ CD138+ subsets (Fig. 1b). Thus, all circulating ASCs in SLE represent proliferative plasmablasts (PB) in different stages of maturation.

Figure 1. SLE flares are characterized by large polyclonal expansions of ASCs.

(a) Polychromatic flow cytometric analysis of SLE flares compared to healthy controls at steady-state and post-vaccination. Representative plots are shown for each state. ASC expansions are documented as the CD27hiCD38hi fraction of IgD− CD19+ B cells. (b) Ki67 staining of peripheral blood ASCs in SLE flares compared to SLE bone marrow ASCs. (c) Clonality of ASCs determined by NGS displayed by size-ranking of individual clonotypes from bottom (smallest) to top (largest) along the extent of the y-axis representing 100% of all the sequences. The x-axis is the normalized lineage size (percentage of the total number of sequences). 2 tetanus and 1 influenza vaccination samples (Tet-2, -3, and Flu 4) are off x-axis scale; maximum lineage size is indicated for these samples to the right of the curve. (d) Size-ranked clones larger than the first occurrence where difference in normalized size of adjacent clones exceeds a threshold value of 0.1% are plotted against the % of all ASC sequences. (n = 5 SLE, 8 vaccination samples; P < 0.05 t-test with unequal variances).

Both ASC subsets as well as naïve (CD19+IgD+CD27−) and IgD− memory cells (CD19+IgD−CD27+, containing isotype-switched and IgM-only cells), were sorted and their rearranged antibody heavy chains were sequenced. NGS data were first analyzed for clonal diversity. Similar to recent studies of influenza vaccination6 and multiple sclerosis7,8, sequences were assigned to individual clones (clonotypes) if they shared VH and JH rearrangements, identical HCDR3 length and a HCDR3 Hamming identity of >85% (Supplementary Note 1). Increasing HCDR3 similarity to >90% did not substantially alter clonal assignments. Therefore, we chose to use a threshold of >85% to allow for a frequency of HCDR3 mutation between ASCs and their naïve precursors similar to the mutation frequency present in HCDR1/2 expressed by ASCs in published studies of influenza responses6 and in our own dataset (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Figs. 1–3).

Given the scarcity of data available regarding the normative distribution of clonal sizes in steady-state and during active immune responses6,9, adjudication of abnormal clonotype expansion is necessarily arbitrary. Accordingly, we used several metrics to consistently measure clonal size, the contribution of large clones and repertoire diversity. Metrics included the percent contributed by any clone to the total number of sequences (Fig. 1c) and the number of clonotypes accounting for the top 20% or 50% of all sequences (D20 and D50, respectively; Supplementary Table 1). In addition, we classified a number of the largest clones as substantially expanded (Fig. 1d). In this context, “expanded lineages” is a heuristic for the number of unusually large clones within a population which is defined as the number of size-ordered lineages after the first occurrence of a delta (between adjacent clone sizes) of 0.1%. Samples were analyzed before and after removal of redundant sequences and minimal change in clonal size relative to the total was observed (data not shown).

SLE ASCs expressed a very polyclonal repertoire in which abnormally expanded clones represented a much smaller fraction of the total compartment and were substantially smaller than in healthy controls vaccinated with either tetanus toxin (tet) or influenza (flu) virus vaccine Fig. 1c,d; Supplementary Table 1). Thus, average D20 in SLE were 199.2 and 126.8 for CD138− and CD138+, respectively, and 21.1 and 10.9 for the combined vaccinated groups. Corresponding average D50 values in SLE were 1721.8 and 1181.6 CD138− and CD138+ ASCs, respectively, and 159 and 125.9 for combined vaccination samples. The percentage of sequences comprising expanded CD138+ ASC clones larger than a difference threshold of 0.1% was much lower in SLE compared to vaccinated healthy controls. Nonetheless, SLE ASCs contained a small number of sizable clonal expansions (2–10 and 0–18 expanded clonotypes in CD138− and CD138+ ASCs, respectively; Fig. 1d). This pattern was most prominent in patients SLE-2 and SLE-4. Thus, the CD138+ D20 in SLE-2 and SLE-4 were only 26 and 31, respectively, with the top clone in SLE-4 accounting for over 6% of 5 × 104 unique sequences obtained from 2 × 105 cells. In SLE-2, the top clone accounted for 2.1% and 1.5% of all CD138− and CD138+ ASCs, respectively.

Naïve B cells were highly polyclonal in SLE and vaccinated healthy controls (Supplementary Table 1; average D20: 473.2 for SLE; 554.5 for flu; and 423 for tet). However, significant clonal expansions (D20=3) were also present in the total naïve compartment of SLE-2, possibly due to presence of an activated fraction of cells within the total naïve compartment (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5). This patient, who was on minimal immunosuppression, experienced a major acute flare, which was accompanied nephritis, central nervous system, hematological and serological manifestations. Similarly, memory cells were highly polyclonal in the flu group and in the SLE group, but striking clonal expansions were displayed after tet vaccination of healthy controls (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

Clonal sizes calculated from sequence numbers could be influenced by mRNA abundance/cell and PCR-induced skewing. However, mRNA abundance should be similar within purified cell subpopulations. A notable exception may apply to populations that might contain a fraction of highly activated B cells possibly expressing higher abundance of IGH mRNA. In this case, the estimated clonal size would be immunologically informative by identifying such population. Finally, PCR skewing for any given VH gene segment should impact equally all subpopulations and clinical samples.

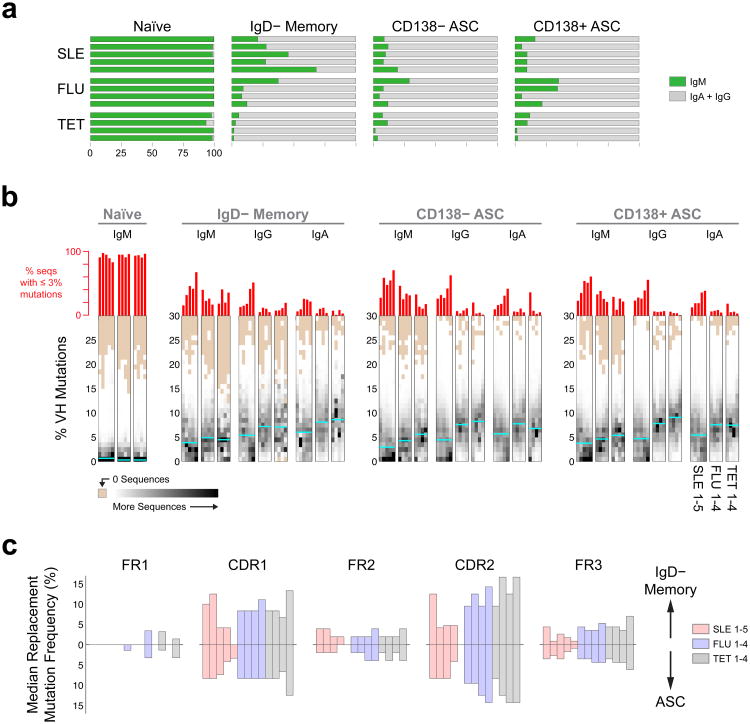

As expected, IgG and IgA isotypes represented the majority of ASC sequences (Fig. 2a). IgM contributed a sizable 5.42–19.53% of all SLE ASC sequences with substantial inter-individual variability observed among vaccinated healthy controls. Of note, the frequency of IgM sequences within the IgD−CD27+ memory cell population was significantly greater in SLE patients compared to post-vaccination healthy controls, 20.9–68.1% and 1.5–37.5%, respectively (Fig. 2a). These numbers are consistent with the frequency of IgM+ memory cells observed by flow cytometry in 120 SLE patients (median of 9.1% with an upper limit of 60.6%; data not shown). In summary, ASCs in flaring SLE patients are highly polyclonal and contain, in addition to class switched sequences, a substantial fraction of IgM sequences that presumably derive from recently activated naïve cells as also seen in repeated HIVgp120 vaccination10, and/or IgM memory cells11.

Figure 2. Isotype distribution and somatic mutation in SLE and healthy vaccinated controls.

(a) Stacked plots indicate proportion of switched (IgG + IgA) and unswitched (IgM) sequences for 13 samples (rows) and four cell subsets (columns). IgD− memory cells include both isotype-switched and IgM-only cells. The IgM-only fraction of memory cells is significantly increased in SLE (p < 0.05, t-test with unequal variances). (b) Heat map histograms of mutation rates for 4 populations, 3 isotypes and 13 subjects. Columns represent a single isotype and population from an individual. Rows are histogram bins representing percent V mutations (bin size is 1%). Shades of gray correspond to bin height (beige corresponds to “0”). Bin heights for each histogram were divided by the total number of sequences for the corresponding isotype/population/individual to normalize the histogram heights and so histogram bin heights sum to 1. Cyan lines show the average of medians for each sample group. SLE ASC fractions displayed a lower average mutation rate compared to vaccinated HC (p < 0.05, t-test unequal variances). Red bars above plots indicate percentage of sequences with mutation rates below 3% and show a significantly higher number of these low-mutated sequences in SLE ASC (p < 0.05, t-test with unequal variances). (c) Replacement mutations (median frequency) found in each region in IgD− Memory (top) and CD138+/- ASC (bottom).

SLE ASCs display lower frequencies of SHM

SHM frequencies were calculated by determining the length of the corresponding germline VH region in each sequence (approximately 285 bp, but varies by VH gene) and ascertaining the percentage of mutations in non-gap bases within that VH segment. SLE ASC fractions displayed a lower average mutation rate compared to vaccinated healthy controls (SLE: 4.98%, vaccinated healthy controls: 7.33%). Interestingly, SLE samples contained a large fraction of less-mutated cells with 32.5% of CD138− ASC and 30.8% of CD138+ ASC sequences containing fewer than 3% mutations (8.55 mutations/sequence based on a germline VH gene of 285 bp) compared with 11.8% of CD138− ASC and 10.0% of CD138− ASC sequences in vaccination samples (Fig. 2b). SLE-4 and SLE-5 contained a particularly large number of less-mutated sequences in ASCs, 39.8 and 52.9%, respectively. These results were validated through single-cell analysis on 771 isotype-switched ASCs obtained from 6 additional SLE patients. Within this cell population, 4% of the VH sequences were unmutated and less-mutated sequences averaged 18.5% with a range of 7.1-38.5% among individual patients.

The median mutation frequencies were substantially higher in the hypervariable CDR compared to framework (FR) regions (average of 6.74% and 3.15% for SLE and 12.35% and 4.57% for vaccinated healthy controls; Fig. 2c). The replacement: silent mutation ratio (R: S) was also higher in CDR (SLE: 5.83 replacement: 0.00 silent mutations and 1.49 replacement: 0.70 silent mutations for CDR and FR, respectively), which are consistent with reference values for influenza-selected ASCs 6 and the post-vaccination results (9.52 replacement: 0.42 silent mutations for CDR and 2.92 replacement: 1.49 silent mutations for FR). Thus, the SLE pattern is consistent with antigen-driven selection of the ASC precursors as expected for pre-existing memory cells and newly recruited naïve cells driven through BCR stimulation.

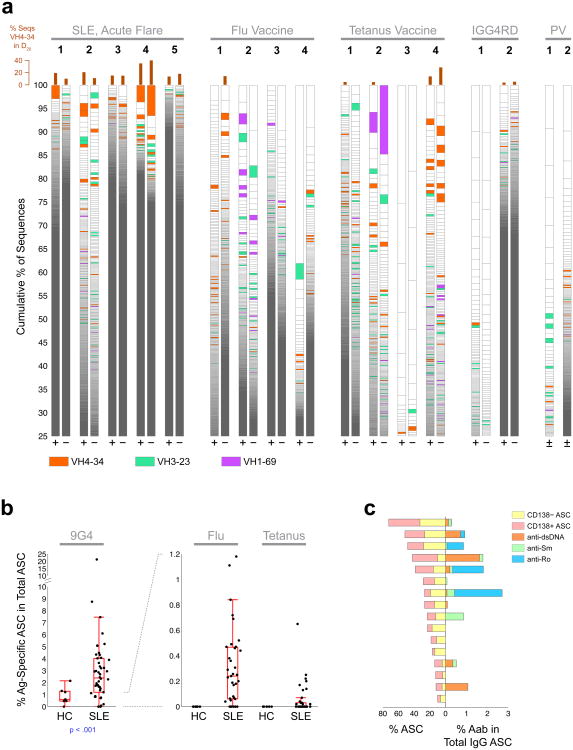

SLE ASC are punctuated by complex VH4-34 clonal expansion

IGH VH utilization was analyzed to understand repertoire complexity. Of the 42–46 functional germline VH gene segments available, VH4-34 accounted for 5.9–19.5% of all SLE ASC sequences but a significantly lower fraction in vaccine responses (1.1–7.6% and 1.6–11.1% for flu and tet vaccines, respectively). In the top 20% of sequences (D20 fraction), this contrast was even more apparent with SLE CD138− ASCs containing an average of 20.7% VH4-34 compared to 2.9% in the vaccination samples (Fig. 3a). Similarly, VH4-34 contributed an average of 19.8% of the D20 fraction of CD138+ sequences in SLE but only 5.3% in the vaccination samples. This highly autoreactive VH gene segment has previously been found to correlate with active SLE in serological studies4,5, and in our studies accounted for 21% of the top 10 ASC clones in SLE patients and contributed substantially to clonal expansions in all 5 patients. In contrast, VH4-34 contributed to ASC expansions in only 2 of 8 vaccinated healthy controls. Conversely, other VH gene segments commonly expressed in the human antibody repertoire (VH3-23 and VH1-69) and overexpressed in influenza, HIV and hepatitis C infections (VH1-69)12, contributed significantly to healthy vaccine responses but much less prominently to SLE ASCs. Moreover, VH4-34 was not common in ASC expanded during the active phase of other antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases, including pemphigus vulgaris and IgG4-related disease (Fig. 3a). Thus, these findings rule out technical skewing and, in keeping with the high specificity for SLE of 9G4 antibodies5, demonstrate a preferential expansion of VH4-34 ASCs in flaring SLE.

Figure 3. Over-representation of IGHV4-34 among SLE ASC clonal expansions.

(a) Plots showing size distribution of individual clonotypes for 17 samples with large IGHV4-34 clones depicted as red bins. For each subject, clonality is depicted for both CD138− ASC (“−”), and CD138+ ASC (“+”). Within each bar, lineages are ordered by size from bottom to top and delineated by horizontal lines. Selected VH-genes (where the normalized lineage size is greater than 0.1% of total sequences) are shown in colors. Bar graphs above the lineage plots show the percentage of sequences in the largest 20% of clones that were IGHV4-34, which was significantly higher in SLE (p < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test). (b) Elispot analysis of antigen-specific ASC. Frequencies of 9G4, Flu, and Tetanus responses are shown as % of total IgG spots. Boxes are 25th to 75th percentiles, lines in boxes are medians, whiskers show extent of non-outlier data (outliers are 1.5 times the interquartile range beyond 25th or 75th percentiles). Note different scales for 9G4 and Flu, Tetanus. (c) Autoantibody frequency (as determined by Elispot), in SLE patients with large increases of ASC (>10% of CD38++CD27++ of IgD−CD19+ cells). Left horizontal bars: frequency of CD138− and CD138+ ASC in individual SLE patients (n=16); right horizontal bars: corresponding percentages of autoantibody specificity out of total IgG ASC.

SLE flares course with generalized ASC increases

ELISPOT assays were used in a larger number of SLE patients to determine autoreactive and anti-microbial responses (Fig. 3b). Disease autoreactivity was assessed against common SLE antigens including dsDNA, Ro and Smith. We also tested for VH4-34-encoded 9G4+ antibodies, which contribute substantially to dsDNA responses and capture additional SLE autoreactivity including anti-apoptotic cell antibodies13,14, thereby providing a more encompassing measure of lupus autoreactivity. Despite the absence of recent immunization or likely natural exposure, flu- and tet-specific cells were highly increased among SLE ASCs (range 0–1.2% and 0–0.65% of all IgG ASCs, respectively), compared to undetectable frequencies in healthy controls. In contrast, even in patients with large ASC increases, common SLE anti-dsDNA, anti-Ro and anti-Smith responses combined, accounted for less than 3% of IgG-producing ASCs (Fig. 3c). Of note, these frequencies closely match similar autoimmune responses in a mouse model of lupus15. The median frequency of 9G4 ASCs was 2.4% and, consistent with our previous results, could account for up to 20% of all IgG ASCs16. Thus, circulating SLE ASCs contain enhanced responses against infectious antigens as well as typical SLE autoantibodies. The latter however account for only a limited fraction of all ASCs and, in keeping with the NGS data, are dominated by 9G4 antibodies.

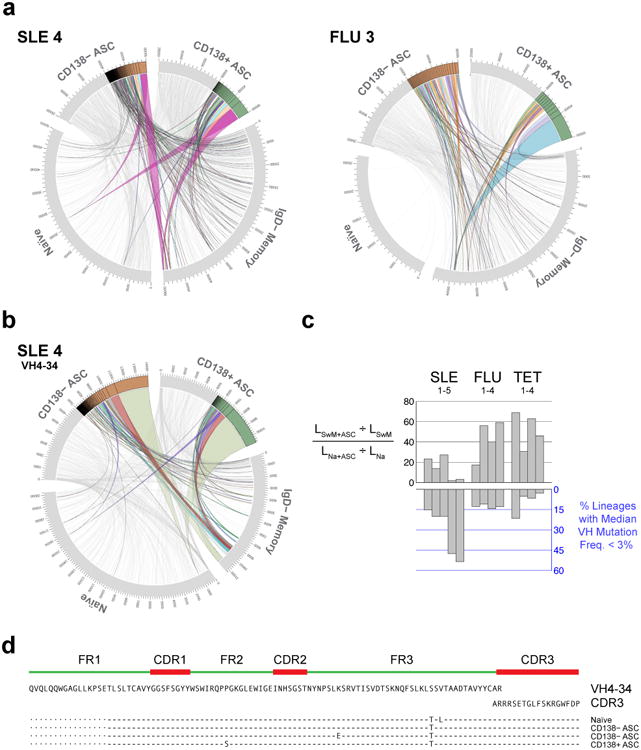

Contribution of Naïve cells to ASC in SLE Flares

ASCs originate either from pre-existing memory B cells or from newly activated naïve B cells through germinal center or extra-follicular reactions11 with both pathways playing a prominent role in mouse models of lupus17-19. To determine the contribution of naïve cells to ASC expansions in SLE, NGS data were analyzed for connectivity using the 85% clonal identification metric method (Supplementary Note 1). Results were quantified using a correction score to account for the variability introduced by differences in the number on input cells in separate individuals as well as sequences available. SLE subjects displayed a significantly higher degree of naïve-to-ASC connectivity than vaccinated controls (Fig. 4a,b). Thus, in SLE the average ratio of IgD− Memory/Naïve cell connections to ASC was significantly lower than in recall responses elicited by vaccination of healthy subjects (Fig. 4c). Notably, naive B cells in patients with the highest frequencies of less-mutated ASCs (SLE-4 and SLE-5) contributed approximately 40% and 25% of all ASC connectivity, respectively. Further illustrating the important contribution of naïve cells, the common ancestor for several of the largest ASC clones could be identified in naïve B cells simultaneously present in the circulation (Fig. 4a,b; a representative alignment is shown in Fig. 4d). A sizeable contribution of naïve cells to ASCs, including the larger clones, was also found in SLE for the predominant VH4-34 (Fig. 4b). In all, we show that naïve B cells are vigorously recruited into the increased ASC response characteristic of SLE flares.

Figure 4. Contribution of naive cells to ASC in SLE flares.

(a) Circos plots integrating multiple molecular features of the antibody repertoire are shown for representative SLE and post-vaccination samples. Plots include the 4 sorted B cell and ASC populations. Sequences numbers are displayed in the outer track; the next track illustrates clonal size and the inner space illustrates connections between populations. Two samples (SLE and day 7 influenza vaccinated subjects) are plotted. Sequences comprising the D50 component of the corresponding population (sequences within the top 50%) are shown in grey for ASC populations whereas lineages accounting for the D20 segment (the top 20% of sequences) and their connections are highlighted in color. All naïve and IgD− memory sequences were highly polyclonal and are depicted in grey. Only connections from naïve and/or IgD− memory to ASC are shown. These plots demonstrate the naïve derivation in SLE of several top D20 CD138− and CD138+ ASC clones including the largest one. (b) A similar contribution of naïve cells to D20 VH4-34 ASC, including the largest clone, is demonstrated for SLE 4 using Circos plots limited to VH4-34 sequences. (c) Top: Comparison of the relatedness of ASC to naïve and SwM. Score is the ratio of the fraction of all SwM clonotypes that are connected to ASC, to the fraction of all naïve lineages connected to ASC. Bottom: percentage of ASC lineages with median mutation frequency < 3%. (d) Alignment of sequences from the largest clone identified in SLE4. Sequences from Naive and ASC share the same HCDR3 and nearly identical VH, and JH regions.

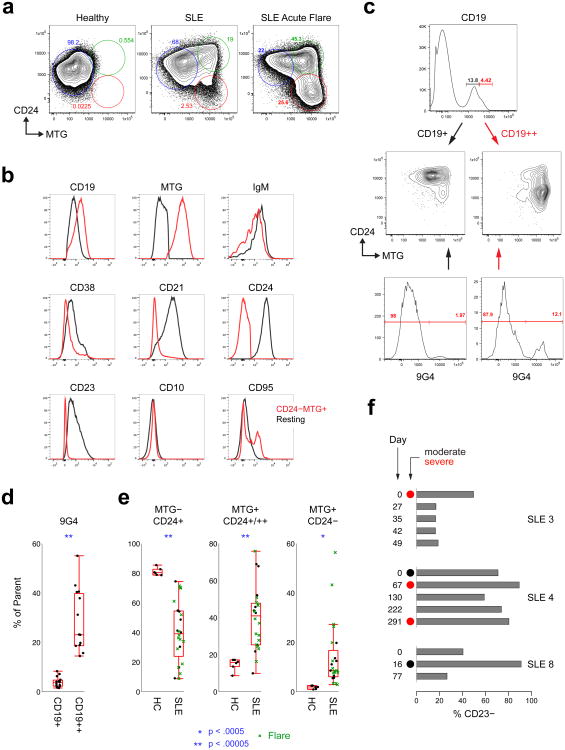

Activated naïve B cells as ASC precursors in SLE

The simultaneous presence of clonally related naïve cells and ASCs suggests persistent naïve B cell activation and differentiation. Thus, we analyzed the phenotype and antibody repertoire of circulating naïve B cells during SLE flares. Multi-chromatic flow cytometry demonstrates that CD19+IgD+CD27− cells, commonly classified as mature naïve B cells, contained three distinct populations defined by mitotracker green (MTG; a mitochondrial dye retained by transitional and activated but not resting naïve cells)20 and CD24 expression. In healthy controls this population was overwhelmingly dominated by resting naïve B cells (Fig. 5). SLE patients have substantial increases of MTG+CD24+/hi transitional cells, as previously reported using alternative markers21. In addition, flaring SLE was also characterized by large increases of MTG+ CD24− cell populations that were nearly absent in healthy controls (Fig. 5a,e). This population was characterized by a CD19hiCD21−CD38loIgMloCD23− phenotype (Fig. 5a–c). While an IgD+MTG+ phenotype is also shared by late transitional cells20, the lack of expression of CD24 and CD38, low expression of IgM and the absence of CD10, strongly mitigate against this alternative. Instead, we surmise that this subset represents recently activated naïve B cells (acN). In support of this interpretation, activated B cells show concomitant CD19 upregulation and CD21 downregulation22,23 and the positive staining/retention of MTG20. This contention is also supported by concordance with disease activity during longitudinal analysis (Fig. 5f). Of relevance, CD19hi activated B cells were highly enriched for autoreactive 9G4 B cells (Fig. 5c), a finding consistent with the prominent contribution of VH4-34 naïve cells to ASC clonal expansions.

Figure 5. Characterization of activated naïve B cells in SLE.

(a) Fractionation of CD19+ IgD+ CD27− cells in active flaring SLE patients identifies three distinct subsets using MTG and CD24 staining. SLE patients have significant expansions of a novel population of MTG+ CD24− cells which may become dominant in actively flaring patients (green symbols in e). These plots are representative of the full data set in e. (b) Extended phenotype of activated (IgD+ CD27− MTG+ CD24−; red histograms) compared to resting naïve B cells (IgD− CD27+ MTG− CD24+; black histogram). (c) The CD19++ fraction of total CD19+ B cells corresponds with the MTG+ CD24- population and is highly enriched in 9G4+ cells relative to the MTG+/- CD24+ fractions. These plots are representative of the full data set in d. (d) The frequency of autoreactive 9G4+ B cells is highly increased within the activated CD19++ fraction of IgD+ CD27− relative to resting CD19+ cells. (e) MTG+ CD24− cells are greatly expanded in flaring SLE subjects. Boxes are 25th to 75th percentiles, lines in boxes are medians, bars show extent of non-outlier data (outliers are 1.5 times the interquartile range beyond 25th or 75th percentiles. (f) Activated cells (in these particular examples identified as the % of CD23− within the IgD+ CD27− naïve cells) were dominant within the naïve compartment during active moderate/severe flares in patients analyzed longitudinally. In one SLE patient (SLE 4), these cells persisted at very high levels between consecutive flares in the context of persistent disease activity by Physician Global Assessment.

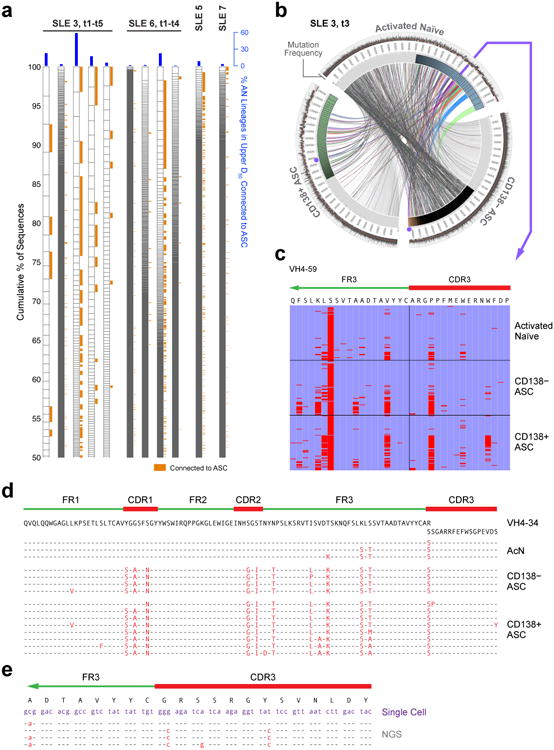

From a repertoire standpoint (Fig. 6a), the salient property of acN cells is increased clonality (28.7-fold higher D20 index relative to healthy control naïve cells) and high degrees of ASC connectivity with up to 32.5% of all acN sequences and 9 of the 10 largest acN clones representing ASC clonal precursors (Fig. 6a,b). Of importance, these measurements varied considerably during longitudinal analyses. This behavior suggests a highly dynamic population and indicate that, as it might be predicted given the necessary lag time between naïve cell activation and clonal expansion of their ASC progeny, single time point analysis substantially underestimates the contribution of newly activated B cells (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. Clonality and connectivity of activated naïve B cells in SLE.

(a) NGS data are displayed as in Fig. 3a to illustrate the clonality of activated naïve cells for four SLE patients, of whom two were analyzed at multiple time points (t1-t5 over 8 weeks for SLE-3 and t1-t4 over 4 weeks for SLE-6). Orange tabs indicate lineages connected to ASC. Blue bars indicate % of acN lineages connected to ASC. (b) Circos plot illustrating clonal expansions and high clonal lineage connectivity of activated naïve cells (IgD+ CD27+ MTG+ CD24−) with ASC populations during SLE flare for the third time point for patient SLE 3. The innermost track indicates the clonality for each population (only highlighted for the top 50% of sequences). The outermost track shows mutation frequencies for the constituent sequences. (c) Alignment of a representative clone containing sequences found in activated naïve, CD138− ASC and CD138+ ASC. The alignment was made to the corresponding germline sequence (VH4-59) and to the CDR3 contained in the sequence with the least VH mutations (common ancestor). Red bars indicate mismatches from the reference sequences. This lineage is highlighted in Fig. 6b as purple dots for the two ASC populations and the arrow for activated naïve cells. (d) Sequence alignment illustrating the co-existence of unmutated/low-mutated acN sequences and highly mutated ASC sequences within a large VH4-34 clone from SLE-6 at a single time point. (e) Sequence alignment of single cell sequences obtained from acN cells and clonally related ASC sequences derived from ASC sequences by NGS 4 months earlier at the time of flare (SLE-3).

Another distinctive feature of acN cells is a substantial frequency of SHM (average of 2.37% in 6 samples compared to only 0.95% for resting naïve B cells), a process associated with germinal center cells that can also occur in activated extrafollicular precursors of ASC17,24. The rarity of mutation in resting naïve cells indicates that this result is not explained either by sequencing errors or VH polymorphisms.

To better understand the dynamics of expanded lupus ASC populations and their naïve precursors, their phylogenetic relationships were constructed using the IgTree software25. This tool identified complex clones in which naïve cells with absent to low degree of SHM (0–2%) co-exist with ASCs with high SHM loads (up to 21.5% mutation frequency). We depict a representative alignment of sequences from a large clonotype that stems from an unmutated acN cell and includes CD138+ and CD138− ASCs that were simultaneously present in the circulation (Fig. 6d). Similar trees could be demonstrated for 55% of the top 20 connected clones analyzed. Given the rate of SHM in antigen-driven mouse autoimmune B cells26, these data would be best explained by prolonged persistence and diversification of acN cells in human SLE previously proposed in mouse models24. This model was supported by the ready identification at the single cell level in an SLE patient of acN B cells clonally related to mutated ASC detected by NGS 4 month earlier (Fig. 6e). Combined, our results indicate that large naïve B cell clones persist and recirculate in SLE for several months.

Contribution of ASC clonal expansions to serum autoantibodies in SLE

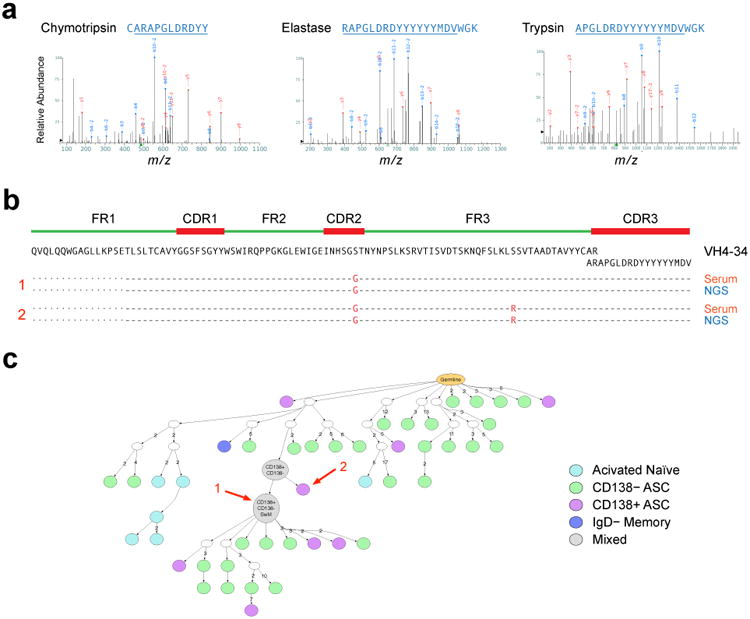

To validate the NGS results and establish the functional consequence of ASC population expansions, affinity-purified serum 9G4 antibodies, obtained from one informative SLE patient experiencing an acute flare, were characterized using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)27. Top candidate antibodies were identified by mapping high confidence peptide spectra. Mass spectra were searched in SEQUEST against the NGS databases obtained from distinct B cell and ASC populations isolated from the same blood sample. Perfect identity was established between the full-length heavy chain protein sequence and NGS sequencess for 39 serum 9G4+ antibodies representing 20 distinct clonotypes. Two clonally related serum 9G4 antibodies that shared the same HCDR3 peptide (Fig. 7a) were identical matches with 2 ASC sequences (Fig. 7b) in the largest VH4-34 clone found in SLE-3. Suggesting a derivation from naïve cells, the protein and corresponding nucleotide ASC sequences were almost devoid of any mutation. Consistent with prolonged ASC persistence and ongoing antibody production, both the serum 9G4 antibody clonotype and the corresponding ASC clones persisted in the circulation for over 8 weeks (Supplemental Fig. 6). Thus, persistent ASC clones directly derived from naïve cells contribute substantially to the serum autoantibody repertoire in SLE.

Figure 7. Serological consequence and cellular derivation of expanded ASC clones in SLE.

(a) Proteomic analysis of affinity-purified serum 9G4 antibodies from SLE-3. Multiple proteolytic digestions resulted in spectra of overlapping peptides spanning the HCDR3 sequence ARAPGLDRDYYYYYYMDV. (b) As illustrated in the alignment, this HCDR3 sequence and two linked full-length VH sequences (separated by a single point mutation) also identified by proteomics, were a perfect match for two ASC sequences identified by NGS in the same blood sample. As illustrated in Supplemental Figure 6, this sequence was consistently found in longitudinal serum and ASC samples. (c) IgTree-based phylogenetic analysis was used to localize the ASC origin of the serum antibody within the largest VH4-34 clone present in SLE 3 at the early flare time point. The arrows mark the exact sequences found by proteomic analysis of patient serum.

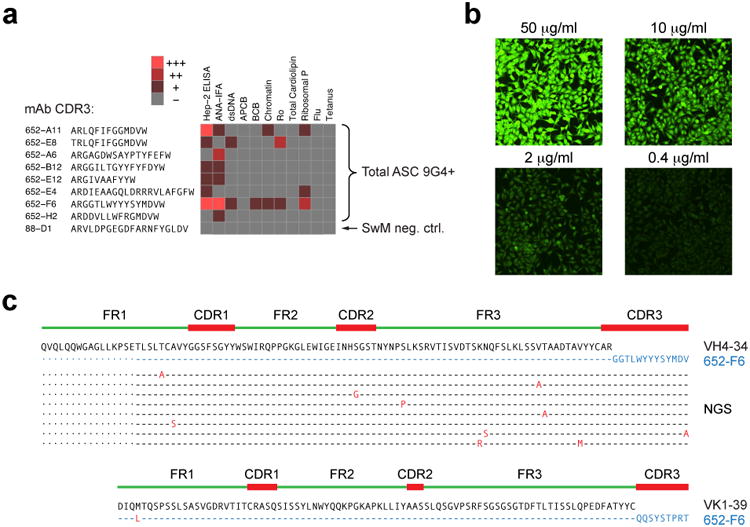

Single cell analysis of ASC autoreactivity and origin

We have previously documented the autoreactivity of 9G4 mAbs derived from SLE naïve and memory cells13. To establish the applicability of those findings to ASC, we sorted 9G4+ plasmablasts from an SLE patient analyzed by NGS 4 months earlier at the time of flare. Productively rearranged VH4-34 sequences and paired light chains were obtained from 44 single cells and classified into 39 separate clonotypes of which 16 corresponded to clones originally identified by NGS. In all, 36% of single ASCs analyzed were clonally related to earlier ASC NGS data with 4.5% representing identical matches, thus corroborating the persistence of ASC. We then generated recombinant mAbs from sequences representative of each clonotype present at the time of flare. 9G4 ASC antibodies displayed substantial autoreactivity including ANA, anti-dsDNA, anti-chromatin, anti-Ro and anti-ribosomal P autoreactivity (Fig. 8a,b). Some antibodies displayed significant auto-polyreactivity against dsDNA, chromatin and ribosomal P autoreactivities which are highly specific for SLE28. However, these antibodies did not react with flu or tetanus antigens (Fig. 8a). A highly autoreactive antibody (652 F6), expressed unmutated heavy and light chains with complete identity to fourth largest VH4-34 ASC clone at the time of flare (Fig. 8c). Combined, these data establish direct naïve derivation of a highly autoreactive ASC clone expanded during a lupus flare. This finding also represents powerful and original evidence for the generation of SLE-specific IgG autoantibodies from germline sequences without the need for somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation.

Figure 8. Autoreactivity of 9G4 ASC in SLE.

9G4+ ASC were sorted from SLE subject 3 four months after flare and H and L chains expressed by single cells were sequenced. (a) Autoreactivity profile of selected mAbs mAbs is shown using a heat map display. ANA, dsDNA, Chromatin, Ro, Cardiolipin, and Ribosomal P reactivity as well as apoptotic cell binding and B cell binding were measured as described 21. ANA was tested by both Hep-2 immunofluorescence (ANA-IFA) and ELISA (Hep-2 ELISA). mAb 652-F6, representing a highly expanded clone found in subject SLE3 at flare, also shows strong auto-polyreactivity. (b) 652-F6 generated strong, dose-dependent ANA-IFA autoreactivity with strong nucleolar staining and homogeneous cytoplasmic staining consistent with anti-ribosomal reactivity also seen by ELISA. (c) 652-F6 expressed a completely unmutated VH4-34 variable region and unmutated light chain. Its VH sequence belonged to a large clonal tree identified by NGS of bulk ASC 4 months prior to the single cell analysis. ASC clonally related sequences are shown in the alignment to illustrate intraclonal diversification despite the persistence of unmutated clonal members in the circulation.

Discussion

Understanding the provenance, repertoire and serological consequences of ASC expansions is essential to unravel SLE pathogenesis and provide therapeutic insights 29. We demonstrate that these ASC express a highly polyclonal repertoire punctuated by large clonal expansions that are dominated by autoreactive VH4-34 cells and shape the serum autoantibody compartment. This profile was present even in a very acute patient with major multi-organ involvement.

Our study represents the first NGS study in SLE and dissects the connectivity among B cell subsets during an ongoing autoimmune response. Indeed, a highly relevant observation is that the two major subsets of circulating ASC (CD138− and the more mature CD138+) are highly interconnected and represent newly produced proliferative plasmablasts in the process of ongoing maturation.

Polyclonal ASC could indicate bystander B-cell activation 30 or antigen-driven stimulation from multiple lupus autoantigens 28. Serological studies in human SLE have argued for generalized activation 15, whereas antigenic drive has been favored in mice 31. In our study, NGS data and simultaneous increases of anti-microbial and autoreactive ASC favor the former possibility. Nevertheless, these mechanisms are not mutually exclusive since multiple cytokines and TLR stimulation, 19,32, could induce bystander activation while promoting clonal expansion of autoreactive cells receiving BCR-transduced signal 1 33,34. Indeed, the latter component is supported by the clonal expansions of VH4-34 ASC with disease-associated autoreactivity.

A central finding is that during SLE flares, a significant contribution to ASC expansion derives from acN cells that survive for months while still serving as precursors of dynamically diversifying ASC. Of note, our analysis must have underestimated naïve participation as the expansion of naïve precursors would occur days to weeks prior to the ASC generation. Moreover, our stringent criteria would have low sensitivity for the detection of clonal relationships between naïve cells and mutated ASC. The relevance of acN is emphasized by temporal relationship with active disease; a high clonality index suggestive of antigen-driven expansion; enrichment in autoreactive 9G4 B cells; and high levels of IgM memory cells, the first memory layer generated from naïve cells both in GC-dependent and independent fashion 11. Enhanced naïve participation would also help explain the lower levels of SHM displayed by SLE ASC relative to memory cells.

Our results provide new insight into the phenotype, magnitude and downstream consequences of naïve B cell activation in SLE. Indeed, the previously recognized expansion of CD21 Low activated B cells was ascribed to CD27+ B cells 23, while other studies did not discriminate transitional/recent immigrant and mature naïve B cell subsets 21, a limitation overcome by incorporating MTG and CD24 20,35. Also in contrast with previous studies, acN cells are CD23-negative, a finding consistent with the CD23 down-regulation induced by sustained BCR activation, TLR9 and IFNα/IFNγ 36, 37,38, all important stimulatory pathways in SLE 32.

ASC expansions during Lupus flares might be expected to represent recall responses to chronically exposed autoantigens as recently shown for Multiple Sclerosis 39,40. Hence, how do SLE acN compete with memory cells presumed to have higher responsiveness, affinity and precursor frequency? These postulates however remain to be tested in chronic human autoimmune diseases, particularly in SLE where many variables and serum factors may enhance the competitiveness of naïve B cells 41. Thus, naïve B cells contain a high frequency of SLE-related autoreactivity 4,42, and thus, a higher total number of autoreactive precursors. Moreover, naïve cells can not only powerfully generate ASC through an extrafollicular pathway but may also be more adept at generating GC 11, 43.

The autoantigens targeted by ASC oligoclonal expansions during SLE flares remain to be elucidated by large-scale single cell analysis. Nevertheless, an autoantigen-driven process is suggested by the pronounced clonal expansion of VH4-34 ASC and the high frequency of VH4-34 acN cells, in both cases with strong disease-associated autoreactivity. Even more significantly for our understanding of the selection of SLE autoreactivity, VH4-34 antibodies generated from sequences shared by acN cells and ASC demonstrate strong autoreactivity of unmutated naïve cells. Previous studies demonstrated significant naïve B cell polyreactivity against non-specific antigens (insulin, ssDNA and LPS 42 and concluded that lupus memory cells with ANA and anti-Ro reactivity require somatic hypermutation of non-autoreactive B cells in the GC 44. Thus, we provide original evidence for unmutated naïve B cells with strong auto-polyreactivity against several Lupus-specific autoantigens including dsDNA, chromatin and ribosomal P antigens. We also provide the first demonstration that acN B cells are directly selected into the autoimmune effector compartment without the need for affinity maturation. This feature is consistent with extra-follicular generation of lupus autoantibodies, a pathway that, while well-defined in mouse models17,18, has remained unexplored in human SLE. The significance of our findings is enhanced by the recent demonstration of accelerated lupus-like autoimmunity mediated by GC-independent IgM autoantibodies 45.

Our study indicates a very long persistence of SLE peripheral naïve B cells and ASC. Mature peripheral B cells in rodents have a life-span of 2-6 weeks which is shortened to just a few days for autoreactive naïve B cells 46, 47. The only in vivo human study available estimated the half-life of circulating naïve cells at 22 days 48. We show that unmutated naïve cells are found concurrently with clonally related ASC with mutational loads expected to accumulate over many weeks according to estimates in lpr mice 24,26. Moreover, we were able to readily identify at the single cell level unmutated autoreactive acN cells 4 months after initial detection by NGS. Such prolonged survival could be explained, at least in part, by the high levels of BAFF characteristic of SLE 49. Similarly, while normal plasmablasts undergo apoptosis in a few days, the persistence of ASC clones in the circulation for at least 8 weeks suggests a much longer lifespan in SLE. This behavior is consistent with the prolonged survival of plasmablasts recently reported in autoimmune Lyn-deficient mice 50.

In summary, we demonstrate that active SLE is characterized by large polyclonal expansions of newly generated ASC populations. These ASC however also contain substantial clonal expansions of antigen-specific autoreactive cells of which a sizeable fraction derives from persistently activated naïve B cells at least in some cases without the need for somatic hypermutation. The aggregate of our results is consistent with a model of sustained and asymmetric differentiation of activated naïve B cells 51, through both extrafollicular pathways and GC reactions 18, a possibility that best explains the composition of genealogical clonal trees observed at a single time point in the blood.

Our study provides a much needed immunological explanation for the clinical benefit of Belimumab (anti-BAFF) and Epratuzumab (anti-CD22), which preferentially impact acN cells 49,52. The B cell populations described herein represent candidate biomarkers for patient segmentation, flare prediction and design of personalized therapies. At a fundamental level, the study of clonally expanded activated naïve B cells and their highly diversified progeny should help unravel the nature of the potentially distinct antigens that trigger the initial activation and subsequent selection of autoreactive B cells in SLE.

Methods

Subjects

4 subjects vaccinated with trivalent influenza vaccine, 4 subjects vaccinated with tetanus vaccine, and 8 SLE patients experiencing acute flares were enrolled in this study at the University of Rochester Medical Center and Emory University between 2010 and 2013. All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Rochester Medical Center and Emory University School of Medicine and informed consent was given by all study subjects. Healthy subjects received the influenza or tetanus toxoid vaccinations Td or combination Tdap as part of routine medical care. SLE patient recruitment outside the annual influenza season and patient history were used to determine absence of recent immunization or likely natural exposure to influenza. Recent tetanus vaccination was also ruled out by history. PBMCs were isolated pre-vaccine, and on days 6–9 for all vaccination subjects; two SLE patients who were experiencing active flares were followed longitudinally at weekly time-points for up to 8 weeks. SLE patients fulfilled ≥ 4 criteria of the modified ACR classification and were routinely evaluated by expert rheumatologists at the University of Rochester Rheumatology Clinic and the Emory Lupus Clinic. Patients were recruited if classified as having a moderate-severe flare according to the SELENA-SLEDAI flare index and were on minimal immunosuppression at the time of flare (only hydroxychloroquine and/or <10 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent glucocorticoid).

Multi-color Flow Cytometry and Sorting

Mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood using ficoll density gradient centrifugation and stained with the following anti-human antibody staining reagents: Goat F(ab')2 Anti-Human IgD- FITC (Invitrogen) or -APC (clone: IgD26, Miltenyi Biotec); Goat F(ab')2 Anti-Human IgM-PE-Cy5; CD3-Pacific Orange (clone: UCHT1), CD14-Pacific Orange (clone: TK4); CD24-PE-A610 (clone: SN3; Invitrogen); CD19-APC-Cy7 (clone: SJ25C1); CD38-Pacific Blue (clone: HB7); CD23-PE-Cy7 clone: M-L233); CD21-PE-Cy5 (clone B-ly4); CD27-PE (clone: L128, BD Pharmingen); CD138-APC (clone: 44F9, Miltenyi Biotec) and mitotracker green. Approximately 0.1–3 × 105 cells were collected for each population using a BD FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences).

NGS of the IGH repertoire

NGS data is deposited at the NCBI sequence read archive (SRA) study accession, SRP057017. Total cellular RNA was isolated from the number of cells outlined in Table 1 using the RNeasy Micro kit by following the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen). Approximately 2 ng of RNA was subjected to reverse transcription using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad). Aliquots of the resulting single-stranded cDNA products were mixed with 50 nM of VH1-VH7 FR1 specific primers and 250 nM Cα, Cμ, and Cγ specific primers preceded by the respective Illumina nextera sequencing tag (oligonucleotide sequences listed below) in a 25 μl PCR reaction (using 4 αl template cDNA) using Invitrogen's High Fidelity Platinum PCR Supermix (Invitrogen). Amplification was performed with a Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) with the following conditions: after an initial step of 95 °C for 5 min, 25–40 cycles (depending on amplification efficiency) of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, ending with a final extension step of 72 °C for 5 min. Products were purified with RapidTip2 (Diffinity Genomics), and Nextera indices were added via PCR with the following conditions: 72 °C for 3 min, 98 °C for 30 s, 5 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 63 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 3 min. Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics) were used to purify the products and they were subsequently pooled and denatured. Single-strand products were sequenced on a MiSeq (Illumina) using the 250bp ×2 v2 or 300bp ×2 v3 kit.

VH1a: 5′-CAGGTKCAGCTGGTGCAG-3′

VH1b: 5′-SAGGTCCAGCTGGTACAG-3′

VH1c: 5′-CARATGCAGCTGGTGCAG-3′

VH2: 5′-CAGGTCACCTTGARGGAG-3′

VH3: 5′-GGTCCCTGAGACTCTCCTGT-3′

VH4: 5′-ACCCTGTCCCTCACCTGC-3′

VH5: 5′-GCAGCTGGTGCAGTCTGGAG-3′

VH6: 5′-CAGGACTGGTGAAGCCCTCG-3′

VH7: 5′-CAGGTGCAGCTGGTGCAA-3′

Cμ: 5′-CAGGAGACGAGGGGGAAAAGG-3′

Cγ: 5′-CCGATGGGCCCTTGGTGGA-3′

Cα: 5′-GAAGACCTTGGGGCTGGTCG-3′

F tag: 5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG-3′

R tag: 5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG-3′

Bioinformatics analysis of NGS Data

An in-house developed informatics pipeline was used for analysis of sequencing data. Full methodology for the data processing, visualization and analysis using this pipeline is outlined in Supplementary Fig. 1. After paired-end reads were joined, sequences were filtered based on a length and quality threshold. Sequences less than 200 bp and sequences with poor overlaps (>8% difference in linked region) and/or high number of bp below a threshold score (sequences containing more than 15 bp with less than Q30, 10 bp with less than Q20, or any bp with less than Q10 scores) were excluded from further analysis. Isotypes were then determined by analysis of the constant region segment of each sequence and a random subset of 150,000 sequences were aligned and analyzed for clonality and for mutations in the V region using the data provided by IMGT/HighV-quest (http://www.imgt.org/HighV-QUEST/). The subset of 150,000 sequences was necessary for the limitations imposed by IMGT/HighV-quest v1.3.1 at the time of preparation of this manuscript. The subset of sequences was also used to relieve computational stress and allow for analysis in reasonable timing. Samples tested at multiple sized subsets did not result in any substantial difference in the clonality or our interpretation of results. After alignment, the sequences were analyzed by a custom program written by the authors in perl and matlab and is provided for download in Supplementary Dataset 1. Sequences were filtered by removing “unproductive” and “unknown” sequences and clusters of sequences were identified based on the clonal identification metric (see below). 50,000 sequences from the final set were then randomly chosen, again to relieve computational stress of the downstream analyses, to retain similar number of sequences in each data set, and for display purposes. All of IMGT/HighV-quest's data was retained through the process and used for mutation calculations and alignment analyses. The frequency and distribution of somatic hypermutation were ascertained on the basis of non-gap mismatches of expressed sequences with the closest germline VH sequence. Mutation frequencies were determined by calculating the percentage of number of V gene mutations relative to number of non-gap V gene bases. Replacement-to-silent mutation ratios were calculated for CDR and framework regions using the average of the median mutation frequencies in the corresponding VH areas. Circular visualization plots were created using circos v0.64 (http://circos.ca/). Clonally expanded genes and primer validity were confirmed with healthy vaccinated controls by single-cell sorted SLE ASC and 5′ RACE (2 replicates were run and an 97% of the ASC 5′ RACE products were also found in the PCR-based assay. All expanded clones were identified.) Validation of VH4-34 sequence quantification was verified by healthy control naive cells spiked with the RAMOS human cell line, which expresses a rearranged VH4-34 (0, 25, 50, and 75% spike-ins resulted in 0, 29.54, 44.48, and 79.6% RAMOS-specific sequences, respectively).

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was used to determine clonal relationships between different B cell subsets and to analyze the structure and diversification of B cell clones. Clonal sequences were aligned to germline sequence using Clustal X (http://www.clustal.org) and genealogical relationships were constructed using the IgTree© program which uses a distance method-based algorithm to find the most likely tree with the highest probability25. This software allows for the possibility that not all intermediate sequences within a B cell clone may have been identified.

Antigen-specific ELISPOT assay

Antigen-specific ELISPOT assays were performed as previously described1 . PBMCs or sorted ASCs or B cell subsets were added to 96-well ELISPOT plates (MAIPS4510 96 well) coated with anti-human IgG (5 μg/ml, Jackson Immunoresearch,), anti-human IgA (5 μg/ml, Jackson Immunoresearch), Trivalent Influenza Vaccine 2009-2010, 2010-2011 (6 μg/ml, Sanofi Pasteur), or 9G4 mAb, which was kindly provided by F.K. Stevenson (University of Southhampton, Southhampton, United Kingdom). After overnight incubation, wells were washed and bound antibodies were detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-human IgG antibody, anti-human IgA antibody or anti-human IgM antibody (all from Jackson Immunoreseach, used at 1 μg/ml) and developed with VECTOR Blue Alkaline Phosphatase Substrate Kit III (Vector Laboratories). Spots in each well were counted using the CTL immunospot reader (Cellular Technologies Ltd). Results were expressed as the ratio of antigen-specific spots/total IgG spots.

Serum IgG Proteomics

Serum proteomics was used to analyze serum antibodies using nano-flow liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry as described27. The 9G4+ antibody fraction was purified from the serum of two of the SLE patients by affinity chromatography using the 9G4 monoclonal antibody. 9G4+ fractions were eluted, verified for 9G4 expression, then digested with chymotrypsin, pepsin, elastase, and trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. High-confidence peptide spectral matches of variable regions were obtained using SEQUEST against a reference database created by next-generation DNA sequencing of the different B cell subsets analyzed from the same patient using the same blood sample.

Recombinant single-cell monoclonal antibodies

Recombinant single-cell monoclonal antibodies were generated and tested for autoreactivity as previously described in our laboratory using nested RT-PCR from RNA isolated from single cells sorted from the populations of interest into 96-well plates13.

ELISA

QUANTALite ANA, dsDNA, Chromatin, Ribosomal P ELISAs (INOVA Diagnostics) and total Anti-Cardiolipin screen ELISA (ALPCO Diagnostics) were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions as described previously 13.

ANA immunofluorescence (ANA-IFA)

Hep-2–coated slides (Nova lite Hep-2, catalog number 708101; INOVA Diagnostics) were incubated in a moist chamber at ambient temperature with 20 μl purified Abs at 30 μg/ml for 30 min, washed in PBS, and incubated for 30 min with FITC-labeled goat anti-human IgG (20 μl). ANA-negative and ANA-positive control sera were included in all experiments. Samples were examined on a confocal microscope, Olympus FV1000/TIRF (Emory University Integrated Cellular Imaging Microscopy Core). Positive staining was determined by comparison with the controls at equal exposure times.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using a two-sample t-test with unequal variances. In some cases, involving comparisons of lineage counts or data with many zeros, a Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. All statistical tests were computed using Matlab (The Mathworks).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Stevenson (Tenovus Laboratories, Southampton, U.K.) for the 9G4 hybridoma and E. Meffre (Yale University) for expression vectors. We would also like to thank the blood donors and research coordinators involved in this study. Supported by grants U19 AI110483 (Autoimmunity Center of Excellence), 5P01AI078907, 5R37AI049660.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: C.M.T. obtained most samples, conducted sample prep and cell sorting, designed and conducted the next-gen sequencing studies, analyzed and interpreted the data, helped to design figures and helped to write the manuscript. C.F.F. and A.F.R. wrote the programs used for next-gen sequencing analysis, helped in data interpretation, produced visualizations of the data, and helped to design and produce the figures. J.D., I.G., S.S., and W.C.C. conducted and analyzed the proteomics studies. T.I. conducted the ELISPOT experiments. A.C. conducted the experiments with single-cell monoclonal antibodies. J.H. obtained the pemphigus samples, conducted some sequencing studies and helped with the analysis. S.J. helped with sequencing analysis. R.J.F. provided the pemphigus samples. R.M. provided the IgTree program and aided in analysis. C.W. provided flow cytometry data and helped with its analysis. F.E-H.L. provided the vaccinated samples and aided in data analysis. I.S. designed and supervised the project, helped in experimental design, analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests: I.S. is a member of Pfizer Visiting Professor Board and in the last years has consulted for Genentech on B cell-depleting agents. F.E-H.L. has grants with Genentech. The other authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

References

- 1.Lee FE, et al. Circulating human antibody-secreting cells during vaccinations and respiratory viral infections are characterized by high specificity and lack of bystander effect. J Immunol. 2011;186:5514–5521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wrammert J, et al. Rapid cloning of high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature. 2008;453:667–671. doi: 10.1038/nature06890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odendahl M, et al. Disturbed peripheral B lymphocyte homeostasis in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2000;165:5970–5979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappione A, 3rd, et al. Germinal center exclusion of autoreactive B cells is defective in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3205–3216. doi: 10.1172/JCI24179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isenberg DA, et al. Correlation of 9G4 idiotope with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:566–570. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.9.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson KJ, et al. Human responses to influenza vaccination show seroconversion signatures and convergent antibody rearrangements. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palanichamy A, et al. Immunoglobulin class-switched B cells form an active immune axis between CNS and periphery in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:248ra106. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern JN, et al. B cells populating the multiple sclerosis brain mature in the draining cervical lymph nodes. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:248ra107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd SD, et al. Measurement and clinical monitoring of human lymphocyte clonality by massively parallel VDJ pyrosequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:12ra23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moody MA, et al. HIV-1 gp120 vaccine induces affinity maturation in both new and persistent antibody clonal lineages. J Virol. 2012;86:7496–7507. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00426-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dogan I, et al. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effector functions. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/ni.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breden F, et al. Comparison of antibody repertoires produced by HIV-1 infection, other chronic and acute infections, and systemic autoimmune disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson C, et al. Molecular basis of 9G4 B cell autoreactivity in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2013;191:4926–4939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenks SA, et al. 9G4+ autoantibodies are an important source of apoptotic cell reactivity associated with high levels of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:3165–3175. doi: 10.1002/art.38138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klinman DM, Steinberg AD. Systemic autoimmune disease arises from polyclonal B cell activation. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1755–1760. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.6.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pugh-Bernard AE, et al. Regulation of inherently autoreactive VH4-34 B cells in the maintenance of human B cell tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1061–1070. doi: 10.1172/JCI12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.William J, Euler C, Christensen S, Shlomchik MJ. Evolution of autoantibody responses via somatic hypermutation outside of germinal centers. Science. 2002;297:2066–2070. doi: 10.1126/science.1073924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shlomchik MJ. Sites and stages of autoreactive B cell activation and regulation. Immunity. 2008;28:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweet RA, Lee SK, Vinuesa CG. Developing connections amongst key cytokines and dysregulated germinal centers in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:658–664. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wirths S, Lanzavecchia A. ABCB1 transporter discriminates human resting naive B cells from cycling transitional and memory B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3433–3441. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims GP, et al. Identification and characterization of circulating human transitional B cells. Blood. 2005;105:4390–4398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masilamani M, Kassahn D, Mikkat S, Glocker MO, Illges H. B cell activation leads to shedding of complement receptor type II (CR2/CD21) Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2391–2397. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wehr C, et al. A new CD21low B cell population in the peripheral blood of patients with SLE. Clin Immunol. 2004;113:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.William J, Euler C, Shlomchik MJ. Short-lived plasmablasts dominate the early spontaneous rheumatoid factor response: differentiation pathways, hypermutating cell types, and affinity maturation outside the germinal center. J Immunol. 2005;174:6879–6887. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barak M, Zuckerman NS, Edelman H, Unger R, Mehr R. IgTree: creating Immunoglobulin variable region gene lineage trees. J Immunol Methods. 2008;338:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A, Wolfowicz CB, Rothstein TL, Weigert MG. The role of clonal selection and somatic mutation in autoimmunity. Nature. 1987;328:805–811. doi: 10.1038/328805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheung WC, et al. A proteomics approach for the identification and cloning of monoclonal antibodies from serum. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:447–452. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan EM. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic markers for autoimmune diseases and probes for cell biology. Adv Immunol. 1989;44:93–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanz I, Lee FE. B cells as therapeutic targets in SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:326–337. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–2202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gharavi AE, Chu JL, Elkon KB. Autoantibodies to intracellular proteins in human systemic lupus erythematosus are not due to random polyclonal B cell activation. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1337–1345. doi: 10.1002/art.1780311101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi J, Kim ST, Craft J. The pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus-an update. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:651–657. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernasconi NL, Onai N, Lanzavecchia A. A role for Toll-like receptors in acquired immunity: up-regulation of TLR9 by BCR triggering in naive B cells and constitutive expression in memory B cells. Blood. 2003;101:4500–4504. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zubler RH, Kanagawa O. Requirement for three signals in B cell responses. II. Analysis of antigen- and Ia-restricted T helper cell-B cell interaction. J Exp Med. 1982;156:415–429. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palanichamy A, et al. Novel human transitional B cell populations revealed by B cell depletion therapy. J Immunol. 2009;182:5982–5993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanten JA, et al. Comparison of human B cell activation by TLR7 and TLR9 agonists. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokota A, et al. Two species of human Fc epsilon receptor II (Fc epsilon RII/CD23): tissue-specific and IL-4-specific regulation of gene expression. Cell. 1988;55:611–618. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delespesse G, Sarfati M, Peleman R. Influence of recombinant IL-4, IFN-alpha, and IFN-gamma on the production of human IgE-binding factor (soluble CD23) J Immunol. 1989;142:134–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stern JNH, et al. B cells populating the multiple sclerosis brain mature in the draining cervical lymph nodes. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:248ra107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palanichamy A, et al. Immunoglobulin class-switched B cells form an active immune axis between CNS and periphery in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:248ra106. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joo H, et al. Serum from patients with SLE instructs monocytes to promote IgG and IgA plasmablast differentiation. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1335–1348. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wardemann H, et al. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sabouri Z, et al. Redemption of autoantibodies on anergic B cells by variable-region glycosylation and mutation away from self-reactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2567–2575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406974111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mietzner B, et al. Autoreactive IgG memory antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus arise from nonreactive and polyreactive precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9727–9732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803644105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chevrier S, Kratina T, Emslie D, Karnowski A, Corcoran LM. Germinal center-independent, IgM-mediated autoimmunity in sanroque mice lacking Obf1. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:12–19. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fulcher DA, Basten A. B cell life span: a review. Immunol Cell Biol. 1997;75:446–455. doi: 10.1038/icb.1997.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cyster JG, Goodnow CC. Antigen-induced exclusion from follicles and anergy are separate and complementary processes that influence peripheral B cell fate. Immunity. 1995;3:691–701. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Macallan DC, et al. B-cell kinetics in humans: rapid turnover of peripheral blood memory cells. Blood. 2005;105:3633–3640. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stohl W, et al. Belimumab reduces autoantibodies, normalizes low complement levels, and reduces select B cell populations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2328–2337. doi: 10.1002/art.34400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Infantino S, et al. The tyrosine kinase Lyn limits the cytokine responsiveness of plasma cells to restrict their accumulation in mice. Sci Signal. 2014 Aug 12;:ra77. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thaunat O, et al. Asymmetric segregation of polarized antigen on B cell division shapes presentation capacity. Science. 2012;335:475–479. doi: 10.1126/science.1214100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobi AM, et al. Differential effects of epratuzumab on peripheral blood B cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus versus normal controls. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:450–457. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.