Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous peginterferon beta-1a over 2 years in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis in the ADVANCE study.

Methods:

Patients were randomized to placebo or 125 µg peginterferon beta-1a every 2 or 4 weeks. For Year 2 (Y2), patients originally randomized to placebo were re-randomized to peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks. Patients randomized to peginterferon beta-1a in Year 1 (Y1) remained on the same dosing regimen in Y2.

Results:

Compared with Y1, annualized relapse rate (ARR) was further reduced in Y2 with every 2 week dosing (Y1: 0.230 [95% CI 0.183–0.291], Y2: 0.178 [0.136–0.233]) and maintained with every 4 week dosing (Y1: 0.286 [0.231–0.355], Y2: 0.291 [0.231–0.368]). Patients starting peginterferon beta-1a from Y1 displayed improved efficacy versus patients initially assigned placebo, with reductions in ARR (every 2 weeks: 37%, p<0.0001; every 4 weeks: 17%, p=0.0906), risk of relapse (every 2 weeks: 39%, p<0.0001; every 4 weeks: 19%, p=0.0465), 12-week disability progression (every 2 weeks: 33%, p=0.0257; every 4 weeks: 25%, p=0.0960), and 24-week disability progression (every 2 weeks: 41%, p=0.0137; every 4 weeks: 9%, p=0.6243). Over 2 years, greater reductions were observed with every 2 week versus every 4 week dosing for all endpoints and peginterferon beta-1a was well tolerated.

Conclusions:

Peginterferon beta-1a efficacy is maintained beyond 1 year, with greater effects observed with every 2 week versus every 4 week dosing, and a similar safety profile to Y1.

Clinicaltrials.gov Registration Number: NCT00906399.

Keywords: Interferon, pegylated, peginterferon beta-1a, relapse, multiple sclerosis, relapse-remitting multiple sclerosis, MRI, phase 3

Introduction

Interferon (IFN) beta has been an effective treatment for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) for many years. However, some currently available IFN beta therapies require injection several times a week because they are rapidly degraded or cleared by the kidney.1 Frequent injections may have an impact on treatment initiation or adherence among patients with RRMS. Peginterferon beta-1a was developed by attaching a poly(ethylene glycol) chain to the parent IFN beta-1a molecule,2 an established process known as pegylation, and is in development for the treatment of RRMS. Pegylation of IFN beta-1a has been shown to improve pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties in humans compared with non-pegylated IFN beta-1a,3 resulting in prolonged exposure, increased biologic activity, and a longer half-life.4,5

ADVANCE is a 2-year Phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study with a 1-year placebo-controlled period evaluating the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous (SC) peginterferon beta-1a administered every 2 or 4 weeks in patients with RRMS.

Year 1 results have been previously reported.6 Briefly, peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks and every 4 weeks significantly improved clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) endpoints versus placebo (with reductions in annualized relapse rate [ARR; primary endpoint], risk of relapse and disability progression, and the number of new or newly enlarging T2 lesions [secondary endpoints]), with a safety profile consistent with that of established IFN beta-1a therapies. During Year 1, every 2 week dosing provided numerically greater reductions relative to every 4 week dosing across relapse and MRI endpoints.

After Year 1, patients randomized to placebo were re-randomized to peginterferon beta-1a (every 2 or 4 weeks) for Year 2 and patients randomized to active treatment in Year 1 remained on the same dosing regimen in Year 2. Here we report the 2-year efficacy and safety results from ADVANCE.

Methods

Study design and participants

Patients were recruited between June 2009 and November 2011 for ADVANCE, a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, Phase 3 study to investigate peginterferon beta-1a in patients with RRMS. Full details of the study design and eligibility criteria have been previously reported.6 Briefly, eligible patients had a diagnosis of RRMS as defined by the McDonald criteria,7 were aged 18−65 years, had a score of 0−5 on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)8 and ≥2 clinically documented relapses in the previous 3 years, with ≥1 of these relapses having occurred within the 12 months prior to randomization. Key exclusion criteria were progressive forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), pre-specified laboratory abnormalities, and prior IFN treatment for MS exceeding 4 weeks or discontinuation <6 months prior to baseline.

During Year 1 of ADVANCE, patients were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to SC injections of placebo, peginterferon beta-1a 125 μg every 2 weeks, or peginterferon beta-1a 125 μg every 4 weeks (starting dose 63 µg, 94 µg at Week 2, target dose 125 µg at Week 4 and thereafter). At the end of Year 1 (Week 48), patients randomized to placebo were re-randomized to peginterferon beta-1a 125 μg every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks (1:1) with the same dose titration as described above (i.e. during Year 2 all patients received dose-blinded peginterferon beta-1a).

The protocol was approved by each site’s institutional review board and was conducted according to the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Every patient provided written informed consent prior to study entry.

Study procedures and endpoints

Methods for ADVANCE have been previously published.6 Briefly, standardized neurologic assessments, including determination of EDSS score by a blinded, EDSS-certified non-treating physician, were carried out every 12 weeks and at the time of suspected relapse (evaluated during unscheduled visits). MRI scans were obtained at Weeks 24, 48, and 96, and were evaluated in a blinded manner at a central MRI reading center.

Relapses were defined as new or recurrent neurologic symptoms not associated with fever or infection, lasting for ≥24 hours, accompanied by new objective neurologic findings, and separated from the onset of other confirmed relapses by at least 30 days, which were confirmed by the independent neurologic evaluation committee (INEC). Disability progression was defined as an increase in the EDSS score of ≥1.0 point in patients with a baseline score of ≥1.0, or an increase of ≥1.5 points in patients with a baseline score of 0, confirmed after 12 and 24 weeks.

Assessments of the following key clinical and MRI measures in patients with available 2-year data were tertiary endpoints of ADVANCE: ARR, proportion of patients relapsed, disability progression (12-week and 24-week), mean number of new or newly enlarging T2 hyperintense lesions, and gadolinium enhancing (Gd+) lesions.

Safety assessments included monitoring and recording of adverse events (AEs), physical examination, vital signs, and clinician assessment of injection sites, and subject assessment of injection pain. Laboratory assessments included electrocardiography, hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis. To assess immunogenicity, patient serum samples were collected pre-dose on Day 1 and Weeks 8, 20, 36, 48, 60, 72, and 96.

Statistical analysis

All efficacy analyses were performed on data from the intent-to-treat (ITT) population (all randomized patients who received at least one dose of active study treatment over 2 years). Statistical tests were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered significant.

To assess efficacy over 2 years in patients who received peginterferon beta-1a starting from Year 1 versus those who received placebo in Year 1, patients who switched from placebo to peginterferon beta-1a in Year 2 were combined as one group (the “delayed treatment” group) and statistical comparisons versus those receiving continuous peginterferon beta-1a were made: ARR (post-hoc), proportion of patients relapsed (post-hoc), and proportion of patients with disability progression (pre-specified) over 2 years.

ARR, defined as total number of relapses divided by patient-years in the study, excluding data obtained after patients switched to alternative MS medications, was analyzed with the use of a negative binomial regression model adjusted for baseline EDSS score (<4 versus ≥4), baseline relapse rate (number of relapses in 3 years prior to study entry divided by three), and age (<40 versus ≥40 years); adjusted ARRs were presented for each group. MRI results are based on all patients with available MRI data. Negative binomial regression was used for analysis of new or newly enlarging hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images (adjusted for baseline number of T2 lesions) and multiple logit regression was used for the analysis of Gd+ lesions (adjusted for baseline number of Gd+ lesions). Time to first clinical relapse (adjusted for baseline EDSS, age, baseline relapse rate, and baseline presence/absence of Gd+ lesions) and time to first disability progression (adjusted for baseline EDSS and age) were analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model. Post-hoc analyses compared the efficacy of every 2 week versus every 4 week regimens over 2 years.

AEs were summarized with the use of descriptive statistics for all patients who received at least one dose of active study treatment, excluding data obtained after patients switched to alternative MS medications. Immunogenicity was measured by an analytically validated cell-based assay to characterize neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) to IFN beta-1a.

Results

Patients

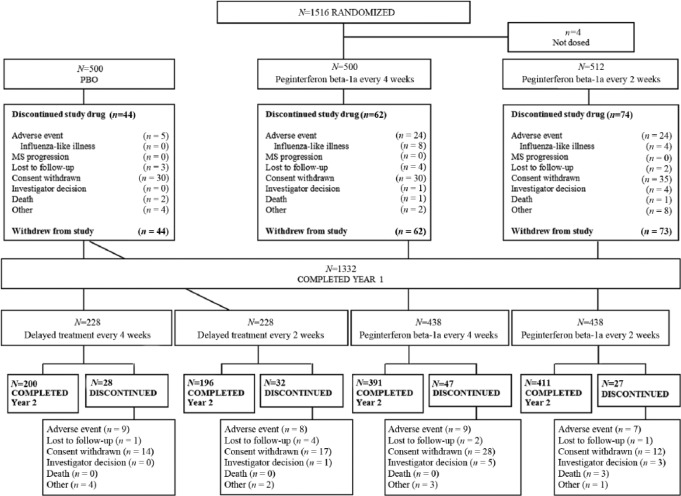

In the overall study population, patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics were generally well balanced across treatment groups.6 Baseline characteristics were similar among the original treatment groups at randomization (Table S1, supplementary materials). Of the 1332 patients completing Year 1, the percentage who completed Year 2 was similar across the continuous peginterferon beta-1a treatment groups and across the placebo-to-active treatment groups (Figure 1). Over 2 years, the rate of discontinuation due to AEs was similar between dosing regimens (6% for each peginterferon beta-1a group).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition – over 2 years.

N, n = number of subjects.

Efficacy

Maintenance of efficacy

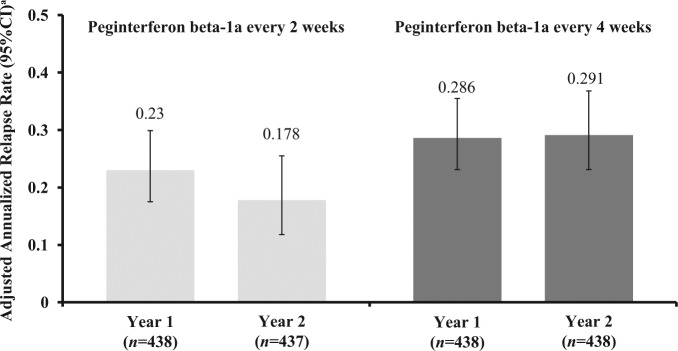

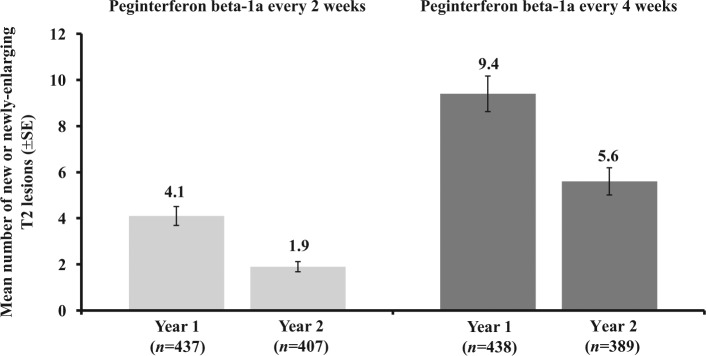

Maintenance of efficacy over 2 years was evaluated by comparing ARR and the number of new or newly enlarging T2 lesions from Year 1 (Baseline to Week 48) and Year 2 (Week 48 to Week 96) for patients receiving peginterferon beta-1a both years. ARR was further reduced with peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks or maintained with peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks in Year 2 relative to Year 1; for the peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks group, ARR was 0.230 (95% CI 0.183–0.291) in Year 1 and 0.178 (0.136–0.233) in Year 2 (Figure 2). In the peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks group, the ARR was 0.286 (95% CI 0.231–0.355) in Year 1 and 0.291 (0.231–0.368) in Year 2 (Figure 2). The mean number of new or newly enlarging T2 lesions was numerically lower in Year 2 (1.9 every 2 weeks; 5.6 every 4 weeks) versus Year 1 for both dosing regimens (4.1 every 2 weeks; 9.4 every 4 weeks) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Annualized relapse rate by study year.

aBased on negative binomial regression, with adjustment for baseline EDSS (<4 vs. ≥4), baseline relapse rate and age (<40 vs. ≥40).

CI: confidence interval.

Figure 3.

New or newly enlarging T2 lesions by study year.

Observed data after subjects switched to alternative MS medications are excluded. Missing data prior to alternative MS medications and visits after subjects switched to alternative MS medications up to week 48 are imputed based on previous visit data assuming the constant rate of lesion development or group mean at same visit.

SE: standard error.

Efficacy in patients who received peginterferon beta-1a for 2 years versus those who switched from placebo in Year 1 to peginterferon beta-1a in Year 2

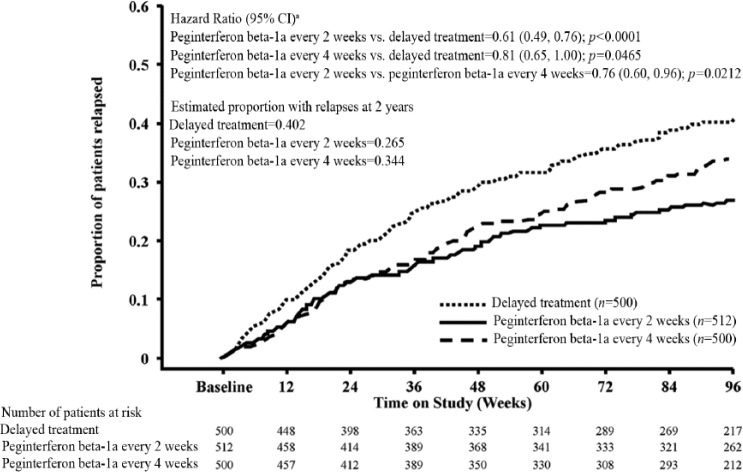

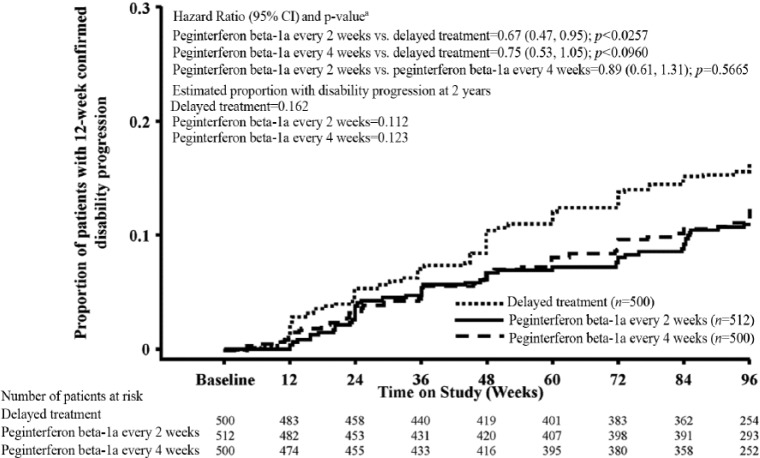

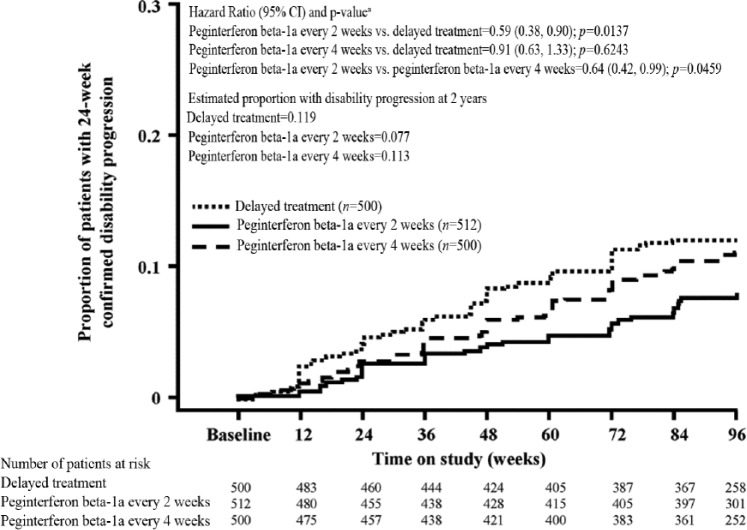

Analysis of clinical endpoints among patients on continuous peginterferon beta-1a and patients originally assigned to placebo showed that peginterferon beta-1a had numerically greater effects. The ARR (95% CI) was 0.351 (0.295–0.418) for the delayed treatment group, 0.221 (0.183–0.267) for the peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks group and 0.291 (0.244–0.348) for the peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks group (Table 1). A post-hoc analysis of continuous peginterferon beta-1a versus the delayed treatment group showed a reduction of 37% (p<0.0001) and 17% (p=0.0906) with peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks and every 4 weeks, respectively. The estimated proportion of patients who relapsed over 2 years was 0.402 for the delayed treatment group, 0.265 for the peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks group, and 0.344 for the peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks group, representing reductions versus the delayed treatment group of 39% (p<0.0001) and 19% (p=0.0465), respectively (Table 1; Figure 4). The estimated proportion of patients with 12-week confirmed disability progression was 0.162 for the delayed treatment group, 0.112 for the peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks group, and 0.123 for the peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks group, representing reductions versus the delayed treatment group of 33% (p=0.0257) and 25% (p=0.0960), respectively (Table 1; Figure 5). The estimated proportion of patients with 24-week confirmed disability progression was 0.119 for the delayed treatment group, 0.077 for the peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks group, and 0.113 for the peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks group, corresponding to a 41% (p=0.0137) and 9% (p=0.6243) reduction versus the delayed treatment group, respectively (Table 1; Figure 6). Patients treated with continuous peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks and peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks had fewer newly enlarging T2 lesions over 2 years than patients in the delayed treatment group, by 67% (p<0.0001) and 16% (p=0.0973), respectively. Statistically significantly reductions in the number of Gd+ lesions were also observed in the every 2 weeks group versus the delayed treatment group (p=0.0002) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical and MRI endpoints over 2 years by original randomization group.

| Endpoint | Delayed treatmenth (n=500) | Peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks (n=512) | Peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks (n=500) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annualized relapse rate at 2 years | |||

| Annualized relapse rate (95% CI)a | 0.351 (0.295, 0.418) | 0.221 (0.183, 0.267) | 0.291 (0.244, 0.348) |

| Rate ratio vs. delayed treatment (95% CI)a | 0.629 (0.500, 0.790) | 0.829 (0.666, 1.030) | |

| p-value vs. delayed treatmenta | <0.0001 | 0.0906 | |

| Rate ratio every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks (95% CI)a | 0.759 (0.600, 0.959) | ||

| p-value (every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks)a | 0.0209 | ||

| Estimated proportion of patients with a relapse at 2 years | |||

| Number of patients relapsed | 192 | 124 | 158 |

| Proportion relapsedb | 0.402 | 0.265 | 0.344 |

| Hazard ratio vs. delayed treatmentc | 0.61 (0.49, 0.76) | 0.81 (0.65, 1.00) | |

| p-value vs. delayed treatmentc | <0.0001 | 0.0465 | |

| Hazard ratio every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks (95% CI)c | 0.76 (0.60, 0.96) | ||

| p-value (every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks)c | 0.0212 | ||

| Disability progression at 2 years (12-week confirmed) | |||

| Number of patients with disability progression | 75 | 51 | 56 |

| Estimated proportion with disability progressiond | 0.162 | 0.112 | 0.123 |

| Hazard ratio vs. delayed treatment (95% CI)e | 0.67 (0.47, 0.95) | 0.75 (0.53, 1.05) | |

| p-value vs. delayed treatmente | 0.0257 | 0.0960 | |

| Hazard ratio every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks (95% CI)e | 0.89 (0.61, 1.31) | ||

| p-value (every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks)e | 0.5665 | ||

| Disability progression at 2 years (24-week confirmed) | |||

| Number of patients with disability progression | 57 | 34 | 52 |

| Estimated proportion with disability progressiond | 0.119 | 0.077 | 0.113 |

| Hazard ratio vs. delayed treatment (95% CI)e | 0.59 (0.38, 0.90) | 0.91 (0.63, 1.33) | |

| p-value vs. delayed treatmente | 0.0137 | 0.6243 | |

| Hazard ratio every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks (95% CI)e | 0.64 (0.42, 0.99) | ||

| p-value (every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks)e | 0.0459 | ||

| New or newly enlarging T2-weighted hyperintense lesions at 2 years | |||

| Number of patients evaluated | 393 | 407 | 389 |

| Adjusted mean number of lesionsf | 14.8 | 5.0 | 12.5 |

| Lesion mean ratio (peginterferon beta-1a:delayed treatment) (95% CI)f | 0.33 (0.27, 0.41) | 0.84 (0.69. 1.03) | |

| p-value (peginterferon beta-1a:delayed treatment)f | <0.0001 | 0.0973 | |

| Lesion mean ratio (every 2 weeks:every 4 weeks) (95% CI)f | 0.40 (0.32, 0.49) | ||

| p-value (every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks)f | <0.0001 | ||

| Gd+ lesions at 2 years | |||

| Number of patients evaluated | 393 | 407 | 389 |

| Mean number of lesions (SE) | 0.5 (0.08) | 0.2 (0.06) | 0.7 (0.12) |

| p-value (peginterferon beta-1a vs. delayed treatment)g | 0.0002 | 0.2169 | |

| Percent reduction (every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks)g | 71 | ||

| p-value (every 2 weeks vs. every 4 weeks)g | <0.0001 | ||

Based on negative binomial regression, with adjustment for baseline EDSS (<4 vs. ≥4), baseline relapse rate, age (<40 vs. ≥40).

Based on Kaplan–Meier product limit method.

Based on Cox proportion hazards model, adjusted for baseline EDSS (<4 vs. ≥4), age (<40 vs. ≥40), baseline relapse rate, and baseline Gd+ lesions (presence vs. absence).

Estimated proportion of patients with progression based on the Kaplan–Meier product limit method.

Based on Cox proportional hazards model, adjusted for baseline EDSS and age (<40 vs. ≥40).

Based on negative binomial regression, adjusted for baseline number of new or newly enlarging T2 lesions.

Percent reduction based on group mean and p-value based on multiple logit regression, adjusted for baseline number of Gd+ lesions.

Delayed treatment group: Patients who received placebo in Year 1 and switched to peginterferon beta-1a in Year 2.

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients relapsed over 2 years (time to first relapse over 2 years).

aBased on Cox proportional hazards model, adjustment for baseline EDSS (<4 vs. ≥4), age (<40 vs. ≥40), baseline relapse rate, and baseline Gd+ lesions (presence vs. absence). Analyses were conducted by combining patients who received placebo in Year 1 and either peginterferon beta-1a every 2 or 4 weeks in Year 2 as one group (delayed treatment).

Figure 5.

Proportion of patients with 12-week confirmed disability progression over 2 years (time to disability progression).

aBased on a Cox proportional hazards model, adjustment for baseline EDSS and age (<40 vs. ≥40). Disability progression is defined as ≥1.0 point increase on the EDSS from a baseline EDSS ≥1.0 sustained for 12 weeks or ≥1.5 point increase on the EDSS from a baseline EDSS of 0 sustained for 12 weeks. Analyses were conducted by combining patients who received placebo in Year 1 and either peginterferon beta-1a every 2 or 4 weeks in Year 2 as one group (delayed treatment group).

Figure 6.

Proportion of patients with 24-week confirmed disability progression over 2 years (time to disability progression).

Disability progression is defined as ≥1.0 point increase on the EDSS from a baseline EDSS ≥1.0 sustained for 24 weeks or ≥1.5 point increase on the EDSS from a baseline EDSS of 0 sustained for 24 weeks. Analyses were conducted by combining patients who received placebo in Year 1 and either peginterferon beta-1a every 2 or 4 weeks in Year 2 as one group (delayed treatment).

aBased on a Cox proportional hazards model, adjustment for baseline EDSS and age (<40 vs. ≥40).

Peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks

Post-hoc analyses of the efficacy of peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks were conducted for clinical and MRI endpoints over 2 years (Table 1). Over 2 years, peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks produced favorable outcomes compared with peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks. The ARR was 0.221 and 0.29 in the every 2 week and every 4 week groups respectively, representing a 24% ([95% CI (4.1–40)]; p=0.0209) reduction versus the every 4 week group (Table 1). Relative to peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks, the risk of relapse was reduced by 24% ([4–40], p=0.0212). Hazard ratios (Table 1) indicated that peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks reduced the risk of 12-week confirmed disability progression by 11% ([95% CI (31–39)]; p=0.5665) and the risk of 24-week disability progression by 36% ([95% CI (1–58)]; p=0.0459) relative to every 4 week dosing.

Patients treated with peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks had 60% (p<0.0001) fewer new or newly enlarging hyperintense T2 lesions over 2 years than patients in the every 4 weeks group (Table 1). Relative to the peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks group, the number of Gd+ lesions over 2 years was reduced by 71% (p<0.0001) in the peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks group.

Safety

Over 2 years, in patients who received at least one dose of peginterferon beta-1a, the incidence of AEs was similar between treatment groups (94% for each peginterferon beta-1a group) (Table 2). The most commonly reported AEs over 2 years were injection site erythema, influenza-like illness, pyrexia, and headache (Table 2). The majority of AEs were mild or moderate in severity; incidence of severe AEs was similar between peginterferon beta-1a dosing groups (21% for every 2 weeks and 20% for every 4 weeks). The incidence of AEs, most common AEs, and severity of AEs in Year 2 were similar to Year 1 (Table S2, supplementary materials).6 The incidence of AEs considered related to treatment by the Investigator in peginterferon beta-1a groups was 90% in the every 2 weeks group and 88% in the every 4 weeks group. The incidence of discontinuation of study treatment due to AEs was 6% in each peginterferon beta-1a group. The incidence of serious AEs was higher in the peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks group (22%) than the every 2 weeks group (16%), with MS relapse the most frequently reported event (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse events, serious adverse events, and discontinuations over 2 years – all patients who received peginterferon beta-1a any time over 2 years.

| Event, n (%) | Peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks (n=740) | Peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks (n=728) |

|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 699 (94) | 687 (94) |

| Most common adverse events (≥10% in any treatment group) | ||

| Injection site erythema | 470 (64) | 433 (59) |

| Influenza-like illness | 377 (51) | 365 (50) |

| Pyrexia | 320 (43) | 298 (41) |

| Headache | 308 (42) | 296 (41) |

| MS relapse | 185 (25) | 222 (30) |

| Myalgia | 140 (19) | 137 (19) |

| Chills | 124 (17) | 123 (17) |

| Injection site pain | 125 (17) | 105 (14) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 97 (13) | 109 (15) |

| Asthenia | 90 (12) | 108 (15) |

| Injection site pruritus | 108 (15) | 82 (11) |

| Back pain | 92 (12) | 89 (12) |

| Arthralgia | 81 (11) | 91 (13) |

| Fatigue | 87 (12) | 72 (10) |

| Pain in extremity | 71 (10) | 74 (10) |

| Nausea | 73 (10) | 63 (9) |

| Adverse events related to study treatment | 668 (90) | 644 (88) |

| Adverse events leading to discontinuation | 41 (6) | 42 (6) |

| Adverse events leading to discontinuation (≥1% in any active treatment group) | ||

| Influenza-like illness | 8 (1) | 12 (2) |

| Any serious adverse events | 120 (16) | 158 (22) |

| Severe adverse events | 152 (21) | 149 (20) |

| Deaths | 4 (<1) | 3 (<1) |

Severe adverse events were defined as symptom(s) that cause severe discomfort; incapacitation or significant impact on subject’s daily life; severity may cause cessation of treatment with study treatment; treatment for symptom(s) could be given and/or subject.

Nine deaths were reported over the 2-year study. Deaths occurring in patients receiving at least one dose of active treatment (n=7) are listed in Table 2 and deaths by study year are listed in Table S2. Of the nine deaths reported over 2 years, four occurred in Year 1 (n=2 in the placebo group and one in each peginterferon beta-1a group) and five occurred in Year 2 (n=3 in the peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks group and n=2 in the delayed treatment every 4 weeks group) (Table S2). None of the deaths during Year 1 (n=4) were assessed as related to study treatment by the Investigator6 (n=2 in the placebo group [n=1 sudden death of unknown cause, n=1 subarachnoid hemorrhage] and n=1 in each peginterferon beta-1a group [every 2 weeks, cause unknown; every 4 weeks, septicemic shock]). Of the five deaths in Year 2, three were considered related to study treatment by the Investigator (n=1 pneumonia/septicemia [every 2 weeks group], n=1 squamous cell carcinoma [delayed treatment to every 4 weeks group] and n=1 aspiration pneumonia [delayed treatment to every 4 weeks group]) (Table S2). An independent data safety monitoring board concluded that these events were not likely related to study drug and did not change the risk–benefit profile of peginteferon beta-1a.

In Year 2, the incidence of potentially clinically significant abnormalities in white blood cell counts (defined as <3.0×109/l), lymphocyte counts (defined as <0.8×109/l), and absolute neutrophil count (defined as ≤1.0×109/l) remained low (≤10% of patients) across peginterferon beta-1a dosing groups (Table S3 in the supplementary materials). The majority of hepatic transaminase elevations were <3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) (Table S4 in the supplementary materials). During Year 2, one patient had asymptomatic concurrent elevation of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) ≥3 × ULN and elevation of total bilirubin >2 × ULN. For both dosing regimens, in majority of subjects who reported hepatic or hematological laboratory abnormalities, the abnormal values returned to normal at the end of Year 2. Lab abnormalities over 2 years are presented in Tables S5 and S6 in the online supplementary materials.

Over 2 years, the incidence (number of patients at risk) of NAbs against IFN (anti-IFN NAbs) (<1% every 4 weeks; <1% every 2 weeks), binding antibodies to IFN moieties (5% every 4 weeks; 8% every 2 weeks), and antibodies against peginterferon (anti-PEG Abs) (8% every 4 weeks; 6% every 2 weeks), were similar for both peginterferon beta-1a dosing groups (Table S7 in the supplementary materials).

Discussion

The results from ADVANCE show that the clinical and neuroradiologic efficacy of peginterferon beta-1a was maintained beyond 1 year of treatment. Compared with Year 1, further reductions in ARR were observed with peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks and the same level of reductions was achieved with peginterferon beta-1a every 4 weeks in Year 2. The number of new or newly enlarging T2 lesions was further reduced in Year 2 compared with Year 1 in the continuous peginterferon beta-1a groups, with greater reductions observed for peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks. The safety profile of peginterferon beta-1a over 2 years was consistent with that in Year 1.6

Assessment of endpoints by original randomization group generally showed that peginterferon beta-1a had greater effects relative to delayed treatment. Importantly, these results demonstrated that the benefits of earlier therapy initiation remain significant for a minimum of 1 year following treatment delay. However, due to the nature of the comparator group, results should be interpreted with caution as the effect sizes are likely underestimates of those against a “true” placebo group. While the every 2 weeks dosing group demonstrated superiority over the delayed treatment group for all endpoints, the every 4 weeks dosing group only demonstrated significant improvement at one endpoint (proportion of relapsed patients). Although comparisons between dosing groups were not pre-specified, assessment of peginterferon beta-1a every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks over 2 years showed that peginterferon beta-1a administered every 2 weeks provided larger statistically significant treatment effects over 2 years versus every 4 weeks administration on ARR, proportion of relapse patients, 24-week disability progression, and all MRI endpoints (12-week disability progression was numerically but not significantly superior).

Comparison of safety results over 2 years with Year 1 showed that the nature, type, and frequency of AEs remained consistent with the longer duration of treatment. The overall incidence of AEs was similar between Year 1 (94% for each peginterferon beta-1a dosing group) and over 2 years (94% for each peginterferon beta-1a dosing group). The most common AEs reported over 2 years were similar to those in Year 1 (injection site erythema, influenza-like illness, pyrexia, and headache). Incidence of severe and serious AEs and rate of infections and serious infections were higher over 2 years than in Year 1 due to the longer duration of follow-up. Safety profiles of peginterferon beta-1a by study year (Year 1 and Year 2) were similar.

The incidence of AEs, serious AEs, and discontinuations due to AEs was also similar across dose regimens (the incidence of serious AEs was slightly higher in the every 4 week dosing group than every 2 week dosing group) and are consistent with the known profiles of IFN beta therapies in MS. For the deaths occurring in Year 1, there was no specific pattern. In Year 2, the nature of deaths was consistent with those expected in the MS population and an independent data safety monitoring board concluded that they did not change the risk–benefit profile of peginterferon beta-1a. The incidence of potentially clinically significant lab abnormalities was low across treatment groups in Year 1 and in Year 2.6

Development of NAbs against IFN beta has been associated with reduced levels of efficacy based on clinical and MRI variables.9–11 Immunogenicity remained low over 2 years; the development of NAbs to IFN beta-1a in Year 1 was similar to that over 2 years (<1%). The development of binding antibodies to IFN beta-1a in Year 1 and over 2 years was also similar (6%) as well as binding antibodies against PEG (7-8%).

Although this study did not directly compare peginterferon beta-1a with other MS therapies, our data are consistent with clinical and MRI findings observed with currently available first-line injection therapies (e.g. 29–34% ARR12–15 12–37% of patients with disability progression,12–14,16 and mean number of new or newly enlarging T2 lesions12,14,17 in 2-year trials). Although direct comparisons are not possible, results suggest that peginterferon beta-1a may provide similar efficacy and safety to that of approved first-line therapies, with the added benefit of a more convenient SC dosing regimen.

Two-year results from ADVANCE showed that clinical and MRI benefits were maintained with SC peginterferon beta-1a beyond the placebo-controlled first year of the study and numerically better efficacy was observed in patients receiving continuous peginterferon beta-1a than those originally randomized to placebo in Year 1. Greater efficacy was observed with every 2 week versus every 4 week administration, and safety results show that peginterferon beta-1a is well tolerated over 2 years. Peginterferon beta-1a offers an effective and safe treatment option with the benefit of less frequent administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the patients who volunteered for this study and the many site staff members who helped to conduct the study. Data and safety monitoring committee members were Brian Weinshenker, Willis Maddrey, Kenneth Miller, Andrew Goodman, Maria Pia Sormani, Burt Seibert. The study was sponsored by Biogen Idec Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA). The authors were assisted in the preparation of the manuscript by Emily Seidman MS, a professional medical writer contracted to CircleScience (Tytherington, UK). Writing support was funded by the study sponsor.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Bernd C. Kieseier has received personal compensation for activities with Bayer Schering, Biogen Idec Inc, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva Neurosciences as a lecturer. Research support from Bayer Schering, Biogen Idec Inc., Merck Serono, Teva Neurosciences

Douglas L. Arnold has received honoraria from Acorda Therapeutics, Bayer HealthCare, Biogen Idec Inc, Coronado Biosciences, EMD Serono, Genentech, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, NeuroRx Research, Novartis, Opexa Therapeutics, Roche, Merck Serono, Teva, Mitsubishi, StemCells, Inc, Teva, XenoPort and salary from NeuroRx Research, and owns stock in NeuroRx Research and research support from Bayer HealthCare.

Laura Balcer has received consulting fees from Biogen Idec Inc., Questcor and Novartis.

Alexey Boyko has received consulting fees from Schering, Merck Serono, Teva, Novartis, Biogen Idec Inc., Nycomed, and Genzyme.

Jean Pelletier has received consulting fees from Allergan, Bayer Schering Pharma, Biogen Idec Inc., Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva, non-profit foundation support from ARSEP, academic research support from PHRC, and unconditional research support from Bayer Schering Pharma, Biogen Idec Inc., BMS, GSK, Merck Serono, Novartis, Peptimmune, Roche, Sanofi, Teva, and Wyeth.

Aaron Deykin, Serena Hung, Sarah I Sheikh, Ali Seddighzadeh, Ying Zhu, Shifang Liu are employees of Biogen Idec Inc.

Peter A Calabresi has received grants/research support from Biogen Idec Inc., Abbott, Novartis and MedImmune, and consulting fees from Abbott, Vaccinex, Prothena, and Vertex.

Funding: This study was funded by Biogen Idec Inc.; Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00906399.

Contributor Information

Bernd C Kieseier, Department of Neurology, Medical Faculty, Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany.

Douglas L Arnold, Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada/NeuroRx Research, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Laura J Balcer, Department of Neurology, New York University, School of Medicine, New York, USA.

Alexey A Boyko, Moscow MS Center at 11 City Hospital and Department of Neurology & Neurosurgery of the RSMRU, Moscow, Russia.

Jean Pelletier, Departments of Neurology and Research, Aix-Marseille Université, CHU Timone, Marseille, France.

Shifang Liu, Biogen Idec Incorporated, Cambridge, USA.

Ying Zhu, Biogen Idec Incorporated, Cambridge, USA.

Ali Seddighzadeh, Biogen Idec Incorporated, Cambridge, USA.

Serena Hung, Biogen Idec Incorporated, Cambridge, USA.

Aaron Deykin, Biogen Idec Incorporated, Cambridge, USA.

Sarah I Sheikh, Biogen Idec Incorporated, Cambridge, USA.

Peter A Calabresi, Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA.

References

- 1. Jain A, Jain SK. PEGylation: An approach for drug delivery. A review. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst 2008; 25: 403–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baker DP, Lin EY, Lin K, et al. N-terminally PEGylated human interferon-beta-1a with improved pharmacokinetic properties and in vivo efficacy in a melanoma angiogenesis model. Bioconjug Chem 2006; 17: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu X, Miller L, Richman S, et al. A novel PEGylated interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis: Safety, pharmacology, and biology. J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 52: 798–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caliceti P, Veronese FM. Pharmacokinetic and biodistribution properties of poly(ethylene glycol)-protein conjugates. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2003; 55: 1261–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kieseier BC, Calabresi PA. PEGylation of interferon-beta-1a: A promising strategy in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2012; 26: 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calabresi PA, Kieseier BC, Arnold DL, et al. Pegylated interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Results from ADVANCE, a randomized, phase 3, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13: 657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria”. Ann Neurol 2005; 58: 840–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983; 33: 1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polman CH, Bertolotto A, Deisenhammer F, et al. Recommendations for clinical use of data on neutralising antibodies to interferon-beta therapy in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 740–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bertolotto A, Deisenhammer F, Gallo P, et al. Immunogenicity of interferon beta: Differences among products. J Neurol 2004; 251(Suppl 2): II15–II24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paolicelli D, D’Onghia M, Pellegrini F, et al. The impact of neutralizing antibodies on the risk of disease worsening in interferon beta-treated relapsing multiple sclerosis: A 5 year post-marketing study. J Neurol 2013; 260: 1562–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: Results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology 1995; 45: 1268–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG). Ann Neurol 1996; 39: 285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis. Lancet 1998; 352: 1498–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. I. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 1993; 43: 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and The University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group. Interferon beta-1b in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: Final outcome of the randomized controlled trial. Neurology 1995; 45: 1277–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paty DW, Li DK. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. II. MRI analysis results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. UBC MS/MRI Study Group and the IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology 1993; 43: 662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.