Abstract

Activated Factor XIII (FXIIIa) catalyzes the formation of γ-glutamyl-ε-lysyl cross-links within the fibrin blood clot network. Although several cross-linking targets have been identified, the characteristic features that define FXIIIa substrate specificity are not well understood. To learn more about how FXIIIa selects its targets, a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization – time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) based assay was developed that could directly follow the consumption of a glutamine-containing substrate and the formation of a cross-linked product with glycine ethylester. This FXIIIa kinetics assay is no longer reliant on a secondary coupled reaction, on substrate labeling, or on detecting the final deacylation portion of the transglutaminase reaction. With the MALDI-TOF MS assay, glutamine-containing peptides derived from α2-antiplasmin, S. Aureus fibronectin binding protein A, and thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor were examined directly. Results suggest that the FXIIIa active site surface responds to changes in substrate residues following the reactive glutamine. The P-1 substrate position is sensitive to charge character and the P-2 and P-3 to the broad FXIIIa substrate specificity pockets. The more distant P-8 to P-11 region serves as a secondary substrate anchoring point. New knowledge on FXIIIa specificity may be used to design better substrates or inhibitors of this transglutaminase.

Keywords: Factor XIII, transglutaminase, coagulation, substrate specificity, kinetics, cross-linking, mass spectrometry

Introductory Statement

In blood coagulation, the serine protease thrombin cleaves the N-terminal portions of the fibrinogen Aα and Bβ chains. The resultant fibrin monomers polymerize non-covalently into linear protofibrils and then laterally into fibers forming a blood clot that is held together by non-covalent forces [1; 2]. To make this blood clot more resistant to degradation, covalent cross-links are introduced into the fibrin network [3; 4]. Thrombin aids in this process by helping to activate Factor XIII (FXIII)1 via cleavage of the FXIII R37-G38 activation peptide bond. The resultant transglutaminase, FXIIIa, then catalyzes the formation of γ-glutamyl-ε-lysyl cross-links within fibrin and fibrin-ligand complexes [5; 6]. The reaction mechanism of FXIIIa involves the thiol group of Cys314 attacking the carboxyamide of a reactive glutamine (Q) side chain. Ammonia is released and a thioester is generated. Deacylation then occurs as the amino group from a Lys (K) side chain targets the thioester. The resultant product of the transglutaminase catalyzed reaction contains an isopeptide bond between the side chains of the Q and K residues [5].

FXIIIa targets several sites within the fibrin αβγ environment leading to formation of a rigid blood clot [7]. Other key FXIIIa substrates include α2-antiplasmin, fibronectin, thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, plasminogen activation inhibitor-1, vitronectin, and S. Aureus fibronectin binding protein A [8]. Although a number of FXIIIa substrates have been identified, an obvious consensus sequence for the Q-containing substrate has been difficult to establish [6; 8; 9; 10; 11].

A variety of methods have been developed to study interactions between FXIIIa and its substrates. In several assays, the lysine-like substrate is detected by colorimetric [12; 13], fluorescent [14; 15], or radioactive methods [16; 17; 18]. With this approach, the glutamine-containing reaction must occur before the lysine-like reaction can be monitored. Another strategy for measuring enzymatic activity is a coupled uv/vis assay in which ammonia released from the reactive glutamines are detected via a separate, secondary colorimetric assay [19; 20; 21; 22]. This resultant ammonia is used to convert α-ketoglutarate to glutamate in an NADH dependent reaction that is monitored at 340nm. Again the glutamine-containing reaction is not being monitored directly. An additional method is to work with synthetic peptides in which the reactive glutamine is replaced with colorimetric Glu-pNA or fluorimetric Glu-AMC [23; 24]. With such reporter groups, the direct release of p-nitroaniline (pNA) or amidomethylcoumarin (AMC) can finally be monitored and is a real strength of this assay design. A drawback is that each substrate needs to have this modified Glu residue introduced into the sequence. Moreover, the bulky reporters group may hinder interactions with the FXIIIa active site surface.

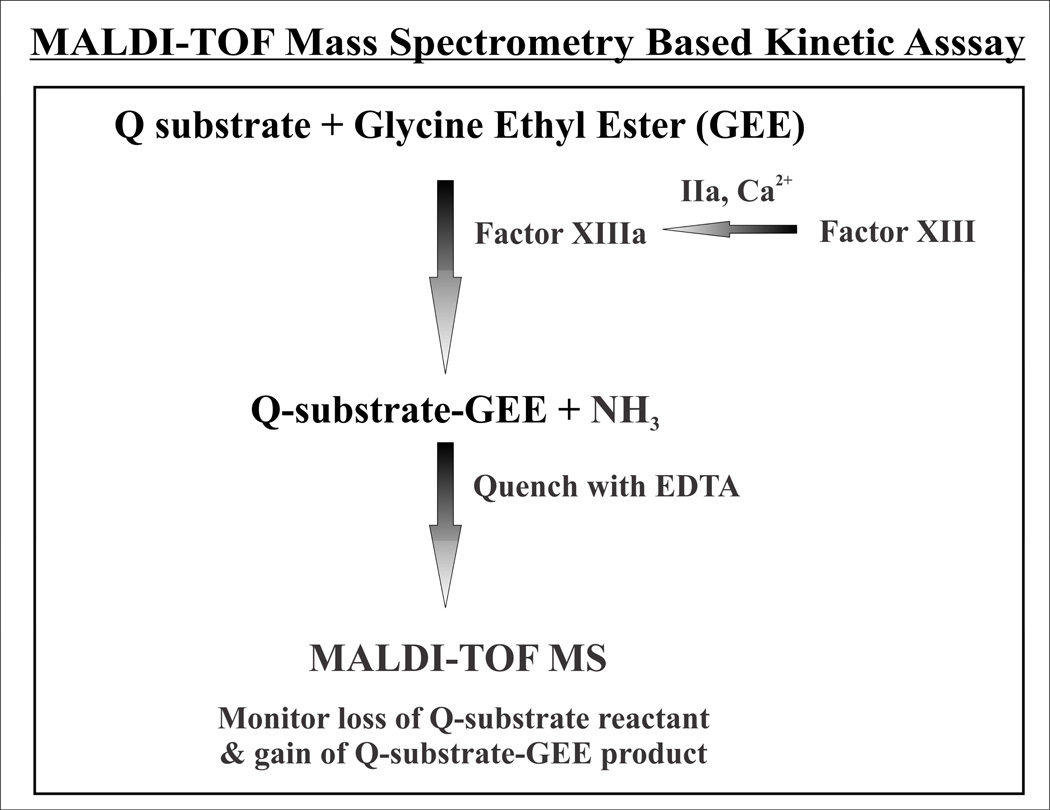

A valuable advance for monitoring FXIIIa kinetics would be an assay that directly records consumption of substrate and formation of product within a single platform. The use of low sample volumes is also desirable. Our newly developed MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry kinetics assay achieves these goals (Fig 1). In the assay, the FXIIIa-catalyzed reaction between a Q-containing substrate and excess glycine ethylester (GEE) is followed. GEE is routinely used as a lysine mimic in the coupled uv/vis assays [19; 20; 21; 22]. The individual transglutaminase reactions are quenched at distinct time points and MALDI-TOF mass spectra are collected to monitor for loss of Q-substrate and gain of the cross-linked product (Q-substrate)-GEE (gain of 86 m/z). Overall, the MALDI-TOF MS kinetics assay is no longer reliant on a secondary coupled reaction, on substrate labeling, or on only detecting the final deacylation portions of the transglutaminase reaction [12; 22; 23].

Figure 1. Flow chart describing the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay.

In this assay, Factor XIII is activated by thrombin in the presence of calcium. The resultant FXIIIa is then responsible for catalyzing the reaction between the Q-containing substrate and glycine ethylester that serves as the lysine mimic. EDTA is added to scavenge calcium away from the FXIIIa and quench the transglutaminase reaction. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry is used to monitor loss of the Q-substrate reactant and formation of the Q-substrate-GEE product.

A series of glutamine containing substrates were chosen to further test the MALDI-TOF MS assay. Using a nomenclature similar to that of the proteases, the reactive Q of FXIIIa substrates occupies the P1 position. Amino acids can be assigned as …P4 P3 P2 P1(reactive Q) and then to the right of the reactive Q as P-1 P-2 P-3 P-4…. (Table 1). Regions to explore in kinetic studies include the P-1 and P-2 positions located near the reactive Q residue and also the putative substrate recognition segment P-8 to P-11 [20; 21; 25]. This P-8 to P-11 segment is proposed to serve as an extra substrate anchor on to the extended FXIIIa active site region. Three FXIIIa substrates containing reactive Q residues include α2-antiplasmin (α2AP), S. Aureus fibronectin binding protein A (S. Aureus Fnb A), and thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) (Table 1). Characteristics of these substrates are described below.

TABLE 1.

FXIIIa Substrate Sequences Aligned Along the Reactive Glutamine Positiona

| Q-containing FXIIIa Substrate | Substrate Sequence Aligned Along the P1 residues |

Masses [M+ H+] m/z |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Free | +GEE | ||

| α2 AP (1–15) Q4 | 1653 | 1739 | |

| α2 AP (1–15) Q4K | 1653 | 1739 | |

| α2 AP (1–15) K12R | 1681 | 1767 | |

| α2 AP (1–15) E3R | 1680 | 1766 | |

| S. Aureus Fnb A (100–110) | 1269 | 1355 | |

| S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) | 1697 | 1783 | |

| S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) Q105S | 1656 | 1742 | |

| S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) R104E | 1670 | 1756 | |

| TAFI (1–15) | 1630 | 1716 | |

| TAFI (1–15) Q5S | 1589 | 1675 | |

FXIIIa substrate peptides derived from the proteins α2-antiplasmin (α2 AP), S. Aureus fibronectin binding protein A (Fnb A), and thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI). The reactive glutamines are bold/underlined and located at the P1 position. The P-1 to P-3 and the P-8 to P-10 positions may participate in promoting binding interactions at the active site.

α2AP (464 residues) serves as a potent inhibitor of the fibrinolytic agent plasmin. Cleavage of the P12–N13 amide bond generates a 452 residue protein starting with an Asn [26; 27]. FXIIIa rapidly cross-links Q2 of N1-α2AP to K303 of the fibrin(ogen) α-chain [26; 28; 29]. While this N1-α2AP is tethered to a blood clot, its C-terminal domain remains free to inhibit plasmin [26]. Previous coupled uv/vis kinetic assays with α2 AP (1–15) (Table 1) have indicated that the Q2 at the P1 position is the reactive glutamine of this peptide with the Q4 at the P-2 position serving a supporting role in binding [20]. α2 AP also contains an 10LLKL12 stretch (P-8 to P-11 region) that is part of a putative substrate recognition exosite [20; 25].

S. Aureus colonizes human tissue during vascular injury by linking its Fnb A to fibrinogen [30; 31]. Similar to the α2AP (1–15) sequence, Fnb A contains glutamines at the P1 and P-2 positions (Table 1) [32; 33; 34]. By contrast, S. Aureus Fnb A has a basic R at the P-1 position whereas α2AP (1–15) has an acidic E. As found in α2AP, S. Aureus Fnb A possesses K residues at the P-8 and P-9 positions.

TAFI modifies lysine residues within the fibrin network thereby reducing the affinity of plasminogen for the blood clot. As a result, less plasmin is generated for fibrinolysis [14; 35; 36]. Similar to α2AP and S. Aureus Fnb A, TAFI also contains two glutamines (Table 1). However with TAFI, a polar serine and the small, flexible glycine are situated between the two glutamines. The second Q residue is thus switched from the P-2 to P-3 position. As observed with α2AP and S. Aureus Fnb A, TAFI (1–15) contains a basic arginine within the P-8 to P-11 region.

Studies to characterize how FXIIIa selects its substrate targets will benefit from the development of assays that directly follow the Q-containing substrate step. Our newly developed MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry kinetics assay achieves this goal by recording the consumption of the Q-containing substrate and formation of the (Q- glycine ethyester) product within a single assay platform. This mass spectrometry based assay is no longer reliant on a secondary coupled reaction, on substrate labeling, or on only detecting the final deacylation portions of the transglutaminase reaction. Using our direct monitoring assay, the kinetic properties of α2AP (1–15), S. Aureus Fnb A (100–110; 100–114), and TAFI (1–15) were successfully determined. Aside from native peptide sequences, individual E, S, and/or R substitutions were also examined. Results indicate that the FXIIIa active site surface responds to changes in the substrate residue positions P-1 and P-2 and also to those of a more distant exosite involving the P-8 to P-11 residues. Additional studies with this MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay will aid in further deciphering the key features of a good FXIIIa substrate or inhibitor.

Materials and Methods

Materials for MALDI-TOF Assay

Human cellular FXIII expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiea was kindly provided by Dr. Paul Bishop (ZymoGenetics Inc, Seattle, WA). The lyophilized FXIII was reconstituted in 18 MΩ deionized water, aliquoted, and stored at −70 °C until future use. The concentration of the FXIII A2 stock solutions were determined on a Cary 100 uv/vis spectrophotometer using an extinction coefficient of 1.49 (ml mg−1 cm−1) at 280 nm. Plasma derived bovine thrombin (Sigma Aldrich) was used to activate the FXIII A2. All the Q-containing substrate peptides (Table 1) were synthesized and purified by New England Peptide (Gardner, MA). The α2AP and TAFI based peptides contained a free N-terminus and an amidated C-terminus. The S. Aureus fibronectin binding A based peptides had an acetylated N-terminus and an amidated C-terminus. Stock peptide concentrations were determined by quantitative amino acid analysis (AAA Service Laboratory, Damascus, OR). Peptide purity was verified in house as being 90% or higher using an Applied Biosystems Voyager DE-PRO MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer.

MALDI-TOF MS assay for kinetics

The final assay volume for each trial was 500 µl. The reaction mix was composed of 2.5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM glycine ethylester, and MALDI Assay Buffer (100 mM Tris-Acetate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG, pH 7.4). The reaction components listed above were prepared in a 1.5 ml reaction tube and incubated at 37°C. FXIII and thrombin were then added to the reaction mix at final assay concentrations of 24–100 nM FXIII and 1–2 nM thrombin. With this assay design, a fresh FXIII activation was carried out for each peptide concentration examined. Consistent activation conditions and quench times were employed across each peptide series. Any losses in transglutaminase activity that may occur upon freeze/thawing of previously activated FXIII substocks would be avoided. For each assay, the FXIII activation was allowed to proceed for 12 minutes and then 140 to 180 nM PPACK were added to inhibit the thrombin. After 5 minutes of incubation at 37°C, a specific concentration of Q-containing peptide ranging from 200 µM to 2000 µM was added to the reaction. Every 3 min up to 18 min or every 5 min up to 30 min, 75 µl of reaction mix were removed and quenched in 5 µl of 160 mM EDTA (10 mM final). After the sixth time point, quenched reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes.

Samples were then prepared for MALDI-TOF MS analysis on an Applied Biosystems Voyager DE-PRO mass spectrometer. C18 reverse phase resin ziptips (Millipore) were employed to reduce buffer salts that can hinder peptide ionization in a MALDI-TOF MS run. The C18 resin in these tips were first wetted with 100% acetonitrile and then rinsed and equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Next, 15 µl of the FXIIIa reaction mix were bound to the C18 resin and then followed by four washes with 0.1% TFA. The sample was released from the C18 resin with 10 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (α-CHCA) containing 1:1:1 ethanol, 0.1% TFA, and acetonitrile. The eluted FXIIIa catalyzed reactions were spotted as one µl aliquots on a stainless steel MALDI plate. Four wells were spotted for each time point. All mass spectral analysis was done in positive, reflector ion mode, 256 shots per spectrum over an m/z range of 800 to 2000 Daltons. A relative intensity of 1 × 104 above the noise was desired. Of the four wells examined, three spectral results were selected for analysis. Moreover, each substrate concentration range was examined in triplicate.

Control experiments were carried out with solutions that contained peptide dissolved in reaction mixes that lacked FXIII. These zero minute time experiments were used to demonstrate the need for using the C18 resin tips for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis (Fig 2). Furthermore, the control studies verified that the peptides were not altered by this added sample preparation procedure.

Figure 2. Evaluating the influence of C18 resin treatment on the quality and integrity of MALDI-TOF mass spectra of Q-containing substrate peptides.

A kinetic reaction mix containing 400 µM α2AP (1–15) Q4K (no FXIII, thus the zero time point) yielded a MALDI-TOF mass spectrum that showed predominantly the sodiated adduct of the peptide. C18 resin treatment using a zip tip reduced the levels of sodiated adducts. Moreover, the S/N of the spectrum increased. A zero time point kinetic reaction mix containing 600 µM S. Aur FnbA (100–114) exhibited similar improvements in MALDI-TOF mass spectra following zip tipping. The integrities of both peptides were maintained. The C18 resin strategy could thus be employed successfully for this kinetic assay project.

To aid in quantification of the MALDI-TOF MS results, an internal standard composed of 220 µM α2AP (1–15) Q2N was tested in the assay design [37; 38]. This non-reactive peptide was added to all the time points after the transglutaminase reaction was quenched with EDTA. As described above, the reaction mixes were subjected to the C18 resin protocol to reduce any interfering buffer salts. MALDI-TOF mass spectra were then collected, and a calibration plot of peak height ratios (substrate peak height /internal standard peak height) versus the substrate concentration was prepared. The slope of the line was used to convert experimental glutamine-containing peptide heights into concentrations. Changes in concentration over time would then be used to determine velocities. Subsequently, we discovered that the internal standard method could not be applied toward all the peptides being investigated. Some of the Q-containing substrate peptides were found to have quite different ionization efficiencies than the non-reactive internal standard α2AP (1–15) Q2N. As a result, it was challenging to use a single peptide-based internal standard for all assays

As an alternative quantification strategy, the following peak height ratio formula was used to determine the amount of reactant remaining. As needed, any residual sodiated and potassiated peptide species still present after the C18 resin zip tip procedure were added to the cation-free peptide peaks to provide the sum of Reactant Peak Heights and/or the sum of Product Peak Heights.

The peptide α2 AP (1–15) Q4K was used as a control sequence to test out the peak height ratio method as a means to quantitate the MALDI-TOF MS kinetic data. Velocities corresponding to loss of Q-containing reactant over time were calculated, and the kinetic data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation. The Km value for this Q-containing peptide was within statistical error of that determined using the traditional coupled uv-vis assay [20]. Moreover, these two Km values were both within statistical error of the value determined using the internal standard α2AP (1–15) Q2N [20].

Since the peak-height ratio method provided comparable results to the other quantification approaches tested, this ratio method was used throughout the kinetics project. Consumption of the Q-substrates could be followed directly and thus velocities calculated. Excel and Sigma Plot were then employed to determine kinetic parameters from the Michaelis-Menten plots and to calculate standard errors of the mean. Each substrate concentration range was independently examined in triplicate. Data were further evaluated with a two-tailed t-test and P-values reported.

Results and Discussions

Although a number of FXIIIa substrates have been identified, how this transglutaminase selects its Q-containing substrate is still not well understood. To further characterize the features that define FXIII substrate specificity, a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry kinetics assay was developed. This assay can directly monitor loss of Q-containing substrate and formation of glycine ethylester (GEE) linked product (Fig 1). Such a single assay platform was applied successfully to probe new peptide substrates with an emphasis on the P-1 and P-2 positions and the more distant region P-8 to P-11.

Validating the MALDI-TOF MS Assay

The Q-reactive substrate α2AP (1–15) Q4K, 1NQEKVSPLTLLKLGN15 (the reactive glutamine is bold and underlined), was selected to confirm that the Km values calculated from the MS assay would be comparable to those obtained with our previously optimized coupled uv/vis approach [20]. In that earlier study, the kcat/Km rankings for a series of α2AP (1–15) Q4X peptides were observed to follow the same trends as those observed for the Km values. The Km values were thus used as a kinetic parameter to compare the two assay formats.

The MALDI-TOF MS method has the advantage of directly monitoring all components in a sample without having to introduce a liquid chromatography step to separate out the species. However with this MS method, it may be necessary to introduce a C18 zip tip step to remove buffer salts that can hinder peptide ionization. Control experiments were thus carried out with free α2AP (1–15) Q4K to evaluate the need for this C18 resin step and to verify that the peptide had not been compromised by this procedure. α2AP (1–15) Q4K was dissolved in all the reaction mix components except the transglutaminase FXIII. This control sample was examined by MALDI-TOF MS in the absence (no Zip) and presence of zip tipping (Zip Tip) (Fig 2). Without the C18 resin wash, it was challenging to observe the α2AP (1–15) Q4K by MALDI-TOF MS and the sodiated peptide was the predominant species in the reaction mix. Following the zip tipping procedure, overall peak intensity increased, S/N levels improved, and the cation-free form of α2AP (1–15) Q4K predominated. There was no evidence that the Q-containing peptide had been compromised by this extra processing step.

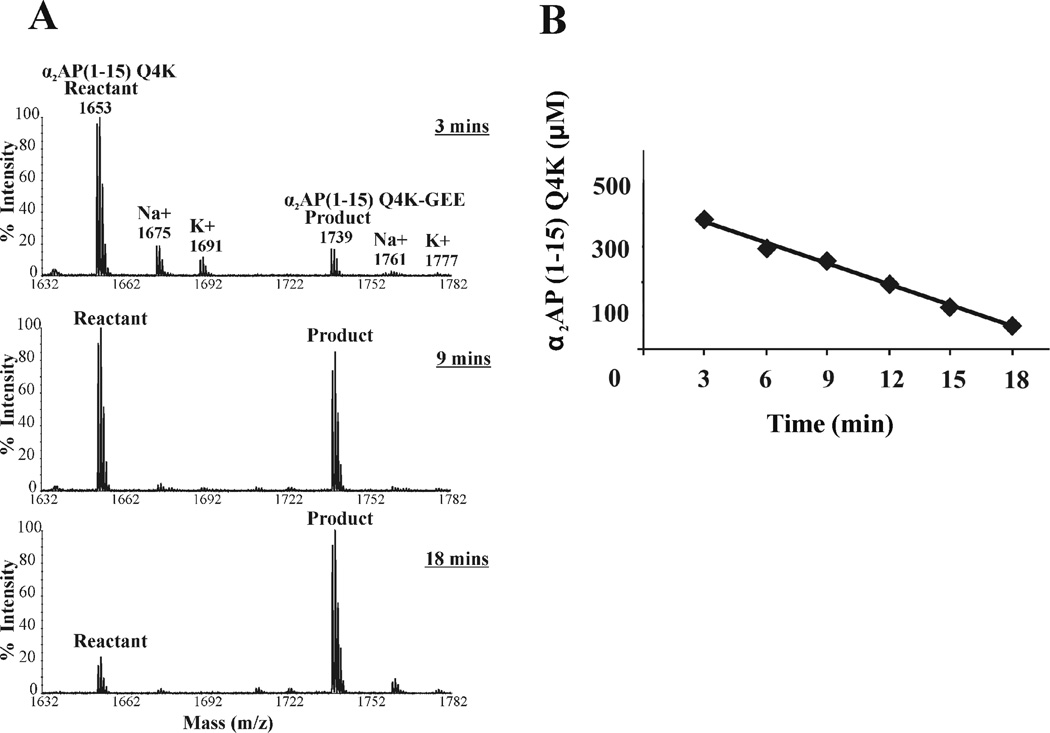

An initial screening of the full mass spectrometry method was thus carried out with the α2AP (1–15) Q4K. The peptide at a final concentration of 400 µM was added to a mixture of 35 nM thrombin-activated FXIIIa, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM GEE, all in Tris-acetate buffer. Aliquots were removed every 3 minutes and quenched with EDTA. The EDTA serves to scavenge the calcium away from the catalytic core domain of FXIIIa. Kinetic reaction samples were then subjected to the C18 resin procedure to remove interfering buffer and salts from the samples. Fig 3 displays representative MALDI-TOF mass spectra for the 3, 9, and 18 minute time points. In Fig 3A, the peak at 1653 m/z corresponds to the original reactant α2AP (1–15) Q4K whereas the cross-linked product α2AP (1–15) Q4K – GEE is observed at 1739 m/z. The more minor populations of sodiated and potassiated peptides are also marked in the spectrum. As the reaction proceeds, the intensity (or amount) of the Q-containing substrate decreases whereas the cross-linked product increases.

Figure 3. Measurement of velocity from a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay.

A) Enzymatic reactions for 400 µM α2AP (1–15) Q4K were quenched at 3, 9, and 18 minutes. The peak at 1653 m/z corresponds to the amount of Q-containing substrate α2AP (1–15) Q4K present after each quench point. The peak at 1739 m/z corresponds to the increasing amount of α2AP (1–15) Q4K cross-linked with glycine ethylester (α2 AP (1–15) Q4K – GEE). Sodiated and potassiated species are also labeled. B) A more extensive plot of remaining α2 AP (1–15) Q4K concentrations as a function of time (3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 min). MALDI peaks were converted into concentrations using the peak height ratio method described in Materials and Methods. The slope of the substrate concentration versus time plot was used to calculate the velocity associated with the 400 µM α2 AP (1–15) Q4K reaction. Velocities were then assessed for a series of peptide substrate concentrations. Each substrate series was examined in triplicate

With an HPLC based assay, the sum of reactant and product peak areas should be a constant value for each substrate concentration. By contrast with MALDI-TOF MS, there may be ionization efficiency and/or matrix crystallization differences across a series of sample spots. As a result, the maximal peak intensity may not be the same for all the sample spots. Consequently, the sum of reactant and product peak heights is not always a constant for a particular substrate concentration. To address this problem, we turned to the peak height ratio method [(Σ reactant peak heights / Σ reactant peak heights + Σ product peak heights) * peptide concentration] to determine quantitatively the amount of reactant remaining after each time point. This approach was found to be a valuable strategy to increase the reproducibility of kinetic data derived from a MALDI-TOF MS based assay. Such a peak height ratio approach has also been used successfully by Jennings et al. to follow production of organophosphate-acetylcholinesterase adducts by MALDI-TOF MS. Moreover, their adduct ratios could be directly correlated with a separate enzyme activity assay [39].

The peak height ratio method was thus used throughout the current FXIIIa kinetics project to determine the concentration of α2AP (1–15) Q4K remaining after each quenched time point. A more extensive plot of Q-substrate concentration remaining versus time (3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18 min) was employed to determine the velocity associated with the 400 µM α2AP (1–15) Q4K reaction (Fig 3B). The MALDI-TOF MS kinetics assay was repeated in triplicate over a series of peptide concentrations, and the velocities corresponding to each peptide concentration were determined. A Km of 316 ± 45 µM was calculated from a Michaelis-Menten plot. This measure of binding interactions was comparable to the Km value of 426 ± 93 µM derived earlier from the coupled uv/vis assay [20]. The MALDI-TOF MS assay could thus be used as an alternative to the coupled uv/vis approach. This MS based assay has the advantage of being able to directly monitor the consumption of Q-containing substrate and production of GEE-linked product.

Examining α2AP (1–15) K12R

A series of peptides based on the α2-antiplasmin sequence α2AP (1NQEQVSPLTLLKLGN15) has been used successfully to explore FXIIIa substrate positions surrounding the reactive glutamine Q2 residue [20; 21; 25]. Some blood coagulation substrates can also take advantage of one or more exosites on their respective enzyme targets [40]. Studies by Gorman and Folk had suggested that residues within the P-8 to P-10 region could promote binding interactions with the FXIIIa active site [41; 42] (Table 1). For the current project, there was interest in further probing the P-10 position that is part of this putative substrate recognition region.

MALDI-TOF MS kinetic studies were carried out with α2AP (1–15) K12R, a substrate sequence where the lysine at the P-10 position is substituted with an arginine containing an ε-amino guanidinium group. MALDI-TOF MS spectra for this Q-containing substrate exhibited an initial reactant peak at 1681 m/z and a product peak at 1767 m/z. Only one glutamine to GEE linked product peak could be followed kinetically (Fig 4). If two GEE units had been cross-linked into the sequence, a product of 1853 m/z (1681 + 172 m/z) would have been observed.

Figure 4. MALDI-TOF mass spectra displaying single Q-peptide - GEE crosslinking reactions that can be followed kinetically.

A) FXIIIa catalyzed reaction involving 175 µM α2AP (1–15) K12R and 5 mM GEE quenched after 18 minutes. The Q-containing peptide (reactant) appears at 1681 m/z and the peptide-GEE (product) at 1767 m/z (1681 + 86). A second product involving both Q residues (1681 + 172 = 1853) is not observed. For the different Q-containing peptides examined in this project, only a single crosslinking reaction could be followed in the MALDI-TOF kinetic assay. B) FXIIIa catalyzed reaction involving 500 µM S. Aur Fnb A (100–110) and 5 mM GEE quenched after 20 minutes. The Q-containing peptide substrate (reactant) appears at 1269 m/z and the peptide-GEE (product) at 1355 m/z. C) FXIIIa catalyzed reaction involving 400 µM S. Aur Fnb A (100–114) and 5 mM GEE quenched after 18 minutes. The Q-containing peptide substrate (reactant) appears at 1697 and the peptide-GEE (product) at 1783. D) FXIIIa catalyzed reaction involving 1200 µM TAFI (1–15) and 5 mM GEE quenched after 25 minutes. The Q-containing peptide (reactant) appears at 1630 m/z and the peptide-GEE (product) at 1716 m/z.

As with the α2AP (1–15) Q4K peptide, a timed reaction series (3, 5, 7, 9, 12, 15, 18 min) for α2AP (1–15) K12R was examined by MALDI-TOF MS (highlights in Fig 5). The kinetic results for the K12R peptide indicate a Km of 108 ± 27 µM and a kcat of 283 ± 28 s−1 (Table 2). Although R12 and the original K12 are both basic, the R12 exhibited a 4-fold improvement in Km relative to the K12 sequence examined previously (108 ± 27µM for R12 versus 459 ± 50 µM for K12) (P < 0.01) [20]. The guanidinium group of arginine 12 may enhance binding interactions by utilizing conjugation between the lone pairs on the nitrogen and the double bond to delocalize the positive charge. As a result, different H-bonding scenarios become available to promote contact with the extended FXIIIa active site region. The single amine at the end of the K12 would have fewer options for manipulating how its side chain character interacts with the FXIIIa surface. In contrast to the Km benefits, the α2AP (1–15) K12R peptide exhibited the lowest kcat value for the peptides examined in this project. Even though the α2AP (1–15) R12 binds more effectively to the FXIIIa surface, this α2AP sequence is not as well oriented for promoting the transglutaminase reaction.

Figure 5. Following FXIIIa catalyzed reactions involving α2AP (1–15) K12R and GEE.

Enzymatic reactions for 100 µM α2AP (1–15) K12R were quenched at 3, 9, and 18 minutes. The peak at 1681 m/z corresponds to the amount of Q-containing substrate α2AP (1–15) K12R present after each quench point. The peak at 1767 m/z corresponds to the increasing amount of α2AP (1–15) K12R cross-linked with glycine ethylester (α2 AP (1–15) K12R – GEE).

TABLE 2.

Binding Interactions Associated with the Reaction of FXIIIa with Q-Substratesa

| Q- Containing FXIIIa Substrate | Km (µM) | kcat (s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| α2AP (1–15) K12R | 108 ± 27 | 283 ± 28 |

| α2AP (1–15) E3R | 594 ±114 | 484 ± 44 |

| S. Aureus Fnb A (100–110) | 971 ± 175 | 387 ± 40 |

| S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) | 571 ± 109 | 535 ± 46 |

| S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) Q105S | 644 ± 122 | 4 5 3 ± 38 |

| TAFI (1–15) | 3330 ± 905 | 559 ± 109 |

Km values were derived from a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay involving Q-containing substrate peptides and glycine ethylester. The assay design is described in Materials and Methods. The results shown represent averages from three independent trials of the concentration ranges. Kinetic values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis methods using SigmaPlot. The error values correspond to standard error of the mean.

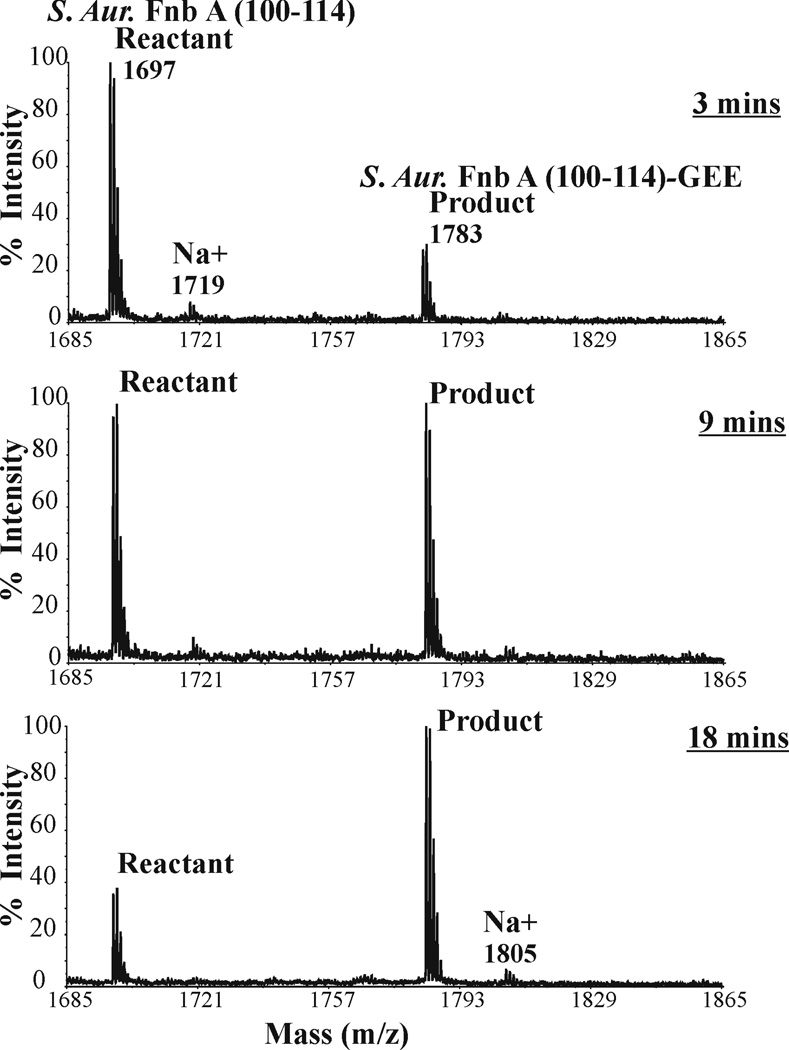

Examining sequences related to S. Aureus Fnb A

Reactive glutamines have already been proposed for S. Aureus Fnb A, but the FXIIIa kinetics have not been reported [32; 33; 34]. Studies began with S. Aureus Fnb A (100–110), a sequence without a potentially reactive lysine, 100SGDQRQVDLIP110. Unlike α2AP (1–15) with its acidic Glu in the 2QEQ4 sequence, the S. Aureus Fnb A (100–110) peptide contains a basic Arg between the two Gln residues, 103QRQ105. MALDI-TOF MS spectra of the quenched reactions revealed that only a single Q-containing GEE linked product could be observed and monitored (Fig 4). The reactant at 1269 m/z increased 86 m/z to generate a product at 1355 m/z. The Km value for this 11 residue peptide was 971 ± 175 µM (Table 2).

The peptide sequence was then extended to S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114), 100SGDQRQVDLIPKKAT114. Similar to α2AP (1–15) with a Lys at the P-10 position, the S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) contains basic Lys residues at the P-8 and P-9 positions. Control studies with free S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) in the reaction mix demonstrated how readily this peptide could be sodiated (Fig 2). The zip tipping procedure diminished the cationic adducts, substantially increased the peptide intensity relative to the baseline, and did not compromise the integrity of the peptide. Subsequent FXIIIa-catalyzed reactions indicated that only one Q-containing GEE linked product peak was observed (free peptide, 1269 m/z, +GEE, 1355 m/z) (Fig 4). In addition, only the glycine ethylester was serving as a lysine mimic in the transglutaminase reaction. The two Lys residues did not participate in intra- or intermolecular crosslinks.

A full series of kinetic time points (3, 5, 7, 9, 12, 15, 18 min) was collected for S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) (highlights in Fig 6). This longer peptide exhibited a Km of 571 ± 109 µM, almost two-fold better than the S. Aureus Fnb A (100–110) (P < 0.05). There was also a kcat increase from 387 ± 40 s−1 to 535 ± 46 s−1 when the FnbA sequence was extended to 100–114 (P < 0.05). A clear improvement in binding interactions thus occurs when S. Aureus Fnb A 100SGDQRQVDLIP110 is increased to 100SGDQRQVDLIPKKAT114. The kcat also undergoes an increase reflecting better turnover into product.

Figure 6. Following FXIIIa catalyzed reactions involving S. Aureus FnbA (100–114) and GEE.

Enzymatic reactions for 600 µM S. Aureus FnbA (100–114) were quenched at 3, 9, and 18 minutes. The peak at 1698 m/z corresponds to the amount of Q-containing substrate S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) present after each quench point. The peak at 1783 m/z corresponds to the increasing amount of S. Aureus FnbA (100–114) cross-linked with glycine ethylester (S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) – GEE).

Earlier studies by Penzes et al. [21] on α2AP (1–12) peptides revealed that a 3-fold increase in Km occurred when the K12 at the P-10 position was removed to produce α2AP (1–11). Subsequent deletions led to further increases in Km, but the fold differences were not as great as with the loss of K12. The minimal length for α2AP to serve as a substrate was 7 residues [21]. Alanine substitutions to the α2AP (1–12) sequence revealed that L10A at the P-8 position hindered the Km the most [21]. With the current S. Aureus Fnb A studies, peptide 100–110 was increased to 100–114. The extra segment (111–114) is proposed to be part of the same critical anchoring segment at the P-8 to P-10 positions as observed with α2AP peptides. Moreover, the beneficial K residues at the P-8 and P-9 positions are also introduced with the longer peptide. The improvements in Km values observed for both the α2AP and the S. Aureus Fnb A peptides support the proposal that FXIIIa does contain a distant exosite that can promote binding interactions separate from the active site. Two substrates with quite different functions take advantage of targeting a FXIIIa exosite. α2-antiplasmin is involved in controlling fibrinolysis whereas Fnb A is used by S. Aureus to anchor on to fibrinogen for colonization [31; 43].

In a prior α2AP (1–15) series, a substrate with improved binding properties could be generated when the Q4 position was substituted with serine (α2AP (1–15) Q4S) [25]. To test if the same effect could be observed with the S. Aureus Fnb A series, a serine was substituted in place of the glutamine at the Q105 position for S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114). S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) Q105S substitution gave a Km of 644 ± 122 µM showing a modest decrease in binding relative to wild-type (Table 2). The two kcat values were similar at 535 ± 46 s−1 for S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) and 453 ± 38 s−1 for S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) Q105S. A Q to S substitution at the P-2 position of S. Aureus Fnb A thus could not generate the 3-fold improvement in Km observed previously for α2AP (1–15, Q4S) [25]. The P-2 to P-7 residues on S. Aureus Fnb A must have greater difficulties accommodating the small polar serine than with α2AP (1–15, Q4S).

In contrast to the 103QRQ105 sequence (P1 to P-2) of S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114), α2AP (1–15) has a glutamic acid between the two glutamines (2QEQ4). To test if introducing a more acidic environment into the S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) would promote binding interactions, the S. Aureus Fnb A R104 was replaced with E104. Unexpectedly, S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) R104E and its GEE-linked products were quite difficult to detect by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry suggesting that ionization efficiency problems were occurring with these reaction mixes. An alternative buffer system with lower salt content was found to help out with this issue (data not shown). However for the current project, the focus was on using the same Tris-acetate, NaCl containing buffer as employed in the previously published coupled uv-vis assays [20].

Because of issues associated with detecting S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) R104E containing species, the opposite substitution in α2AP (1–15) was tested. The 2QEQ4 of α2AP (1–15) was replaced with an E3R substitution to give a 2QRQ4 sequence. The basic arginine at the P-1 position showed an increase in Km (594 ± 144 µM versus the 316 ± 45 µM for α2AP E3) reflecting a decrease in binding interactions. Interestingly, the Km of α2AP (1–15) E3R (594 ± 144 µM) now approached that of S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) (571 ± 109 µM). The kcat value of 484 ± 44 s−1 was also comparable to the 535 ± 46 s−1 of Fnb A 100–114 (Table 2).

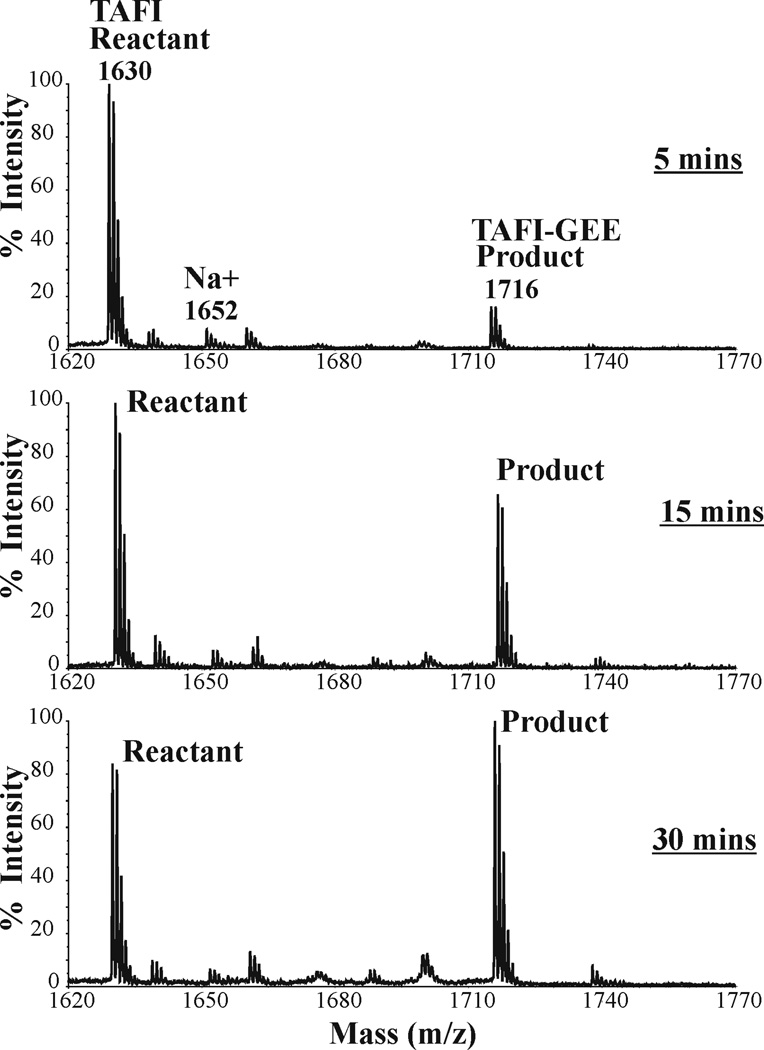

Examining sequences related to TAFI

Thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) was the next candidate to be investigated [14; 35; 36]. The TAFI (1–15) sequence 1FQSGQVLAALPRTSR15 has a serine and glycine between the two glutamines. The P-2 position glutamine that was found to be valuable for α2 AP binding interactions is now shifted to the P-3 position. Interestingly, there is an arginine at the P-10 position.

A review of the MALDI kinetic spectra indicates that only one of the Q residues could be monitored kinetically (Fig 3, and highlighted time series in Figure 7). The TAFI peptide at 1630 m/z increased by a single 86 m/z to 1716 m/z. A second product at 1802 m/z was not detected. A Km of 3330 ± 905 µM was obtained for TAFI (1–15), a value more than 5-fold weaker than what was observed for α2AP (1–15) K12R (Km of 108 ± 27 µM) and S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) (Km of 571 ± 109 µM) (Table 2). The higher Km for TAFI (1–15) indicates that this sequence exhibits much weaker binding interactions with the FXIIIa active site region than the two other substrates tested. The kcat was comparable to that of S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114). A Q5S substitution generated a TAFI sequence that exhibited an even weaker Km and full scale kinetics were not performed.

Figure 7. Following FXIIIa catalyzed reactions involving TAFI (1–15) and GEE.

Enzymatic reactions for 1200 µM TAFI (1–15) were quenched at 3, 9, and 18 minutes. The peak at 1630 m/z corresponds to the amount of Q-containing substrate TAFI (1–15) present after each quench point. The peak at 1716 m/z corresponds to the increasing amount of TAFI (1–15) cross-linked with glycine ethylester (TAFI (1–15) – GEE).

α2AP (1–15) and S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) both contain a single, charged amino acid between the two glutamines. By contrast, TAFI has the polar serine and the small and flexible glycine between the two glutamines. Moreover, a review of TRANSDAB [8] reveals few examples of substrates with a Q at this P-3 position. It is important to point out that the loss in binding interactions occurs even though TAFI contains a beneficial R at the P-10 position. The higher than expected Km value is proposed to be due either to the non-optimal 2QSGQ5 sequence and/or difficulties anchoring the 10LPRTSR15 sequence to a distant FXIIIa surface. Physiologically, α2-antiplasmin is a major substrate for FXIIIa and plays a vital role in regulating fibrinolysis and fibrin architecture [43]. Amino acid properties within the TAFI (1–15) sequence likely contribute to making this protein a significantly weaker transglutaminase catalyzed substrate.

Examining the X-ray Crystal Structures of FXIIIA2

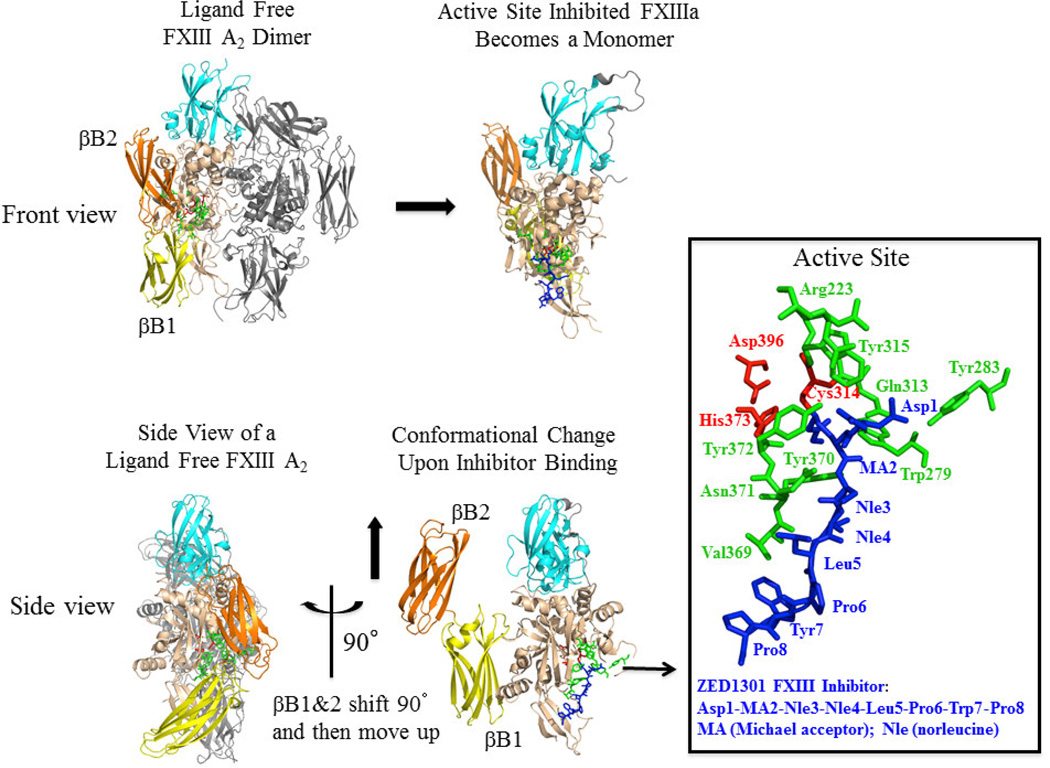

More structural information on the FXIIIa active site region will help in defining the features that control the substrate specificity of transglutaminases. The X-ray crystal structures reported thus far for the activated FXIII A2 dimer, however, have all been in the closed conformation with access to the active site region obstructed [44; 45]. The first crystal structure of an inhibitory peptide bound to nonproteolytically activated FXIII A2 was published in late 2013 by Stieler et al. [46]. The inhibitory peptide contains a glutamine side chain analog that attaches covalently to the catalytic Cys 314 via Michael Addition [46]. The sequence of the ZED1301 inhibitory peptide includes Ac-Asp-MA(Michael Acceptor)-Nle-Nle-Leu-Pro-Trp-Pro-OH. The MA unit is composed of an electrophilic α, β unsaturated carbonyl compound that serves as a glutamine side chain mimetic.

For the crystallization project, the FXIII A2 unit was nonproteolytically activated with 100 mM calcium [46]. Three calcium ions were found to be bound to a single FXIII A subunit, and these cations assisted in maintaining the final transglutaminase conformation. In the presence of the Michael Acceptor containing peptide, the FXIII A2 dimer unit dissociated into two monomeric A subunits (Fig 8, Panel A, front view of FXIII). A side view of the active site- inhibited monomer (Fig 8, Panel B) reveals that in response to adding ZED1301, the FXIII β-barrel-1 and β-barrel-2 domains rotated horizontally (90°) away from the catalytic core region and were directed upwards closer to the β-sandwich domain. For the first time, it was possible to see an exposed FXIIIa active site region containing a bound ligand. A review of the catalytic site (accommodating ligand residues P2 to P-2) confirms the presence of the Michael Acceptor group at the P1 site covalently bound to the catalytic FXIIIa C314 located within the enzyme’s S1 subsite. The remainder of ZED1301 becomes directed toward what Stieler et al. call the hydrophobic site (contains S-3 to S-6 enzyme subsites that accommodate the P-3 to P-6 ligand residues) [46]. FXIIIa residues that interact at or near the ZED1301 peptide include W279, Y283, Q313, Y315, R223, V369, Y370, N371, Y372 (highlighted in green in Fig 8). A review of these FXIIIa residues confirms that the substrate binding region for the ZED1301 inhibitory peptide (Ac-Asp-MA(Michael Acceptor)-Nle-Nle-Leu-Pro-Trp- Pro-OH) is quite hydrophobic with some additional polar character.

Figure 8. Examining the effects of the Michael acceptor inhibitor ZED1301 on the structural properties of Factor XIIIa.

Unactivated cellular FXIII in its ligand free state exists as an A2 dimer. β-barrels 1 (yellow, βB1) and β-barrels 2 (orange, βB2) are labeled. Nonproteolytically activated FXIIIa dissociates into two monomers upon binding the Michael acceptor ZED1301 [46]. The βB1 & βB2 domains shift 90° and then move upwards in response to the inhibitor. For the first time, the active site region of FXIIIa can be examined. In the highlighted panel, the ZED1301 ligand (Asp1- MA2-Nle3-Nle4-Leu5-Pro6-Trp7-Pro8) is blue and the FXIIIa catalytic triad (Cys 314, Asp396, and His373) is red. Cys 314 forms a covalent complex with the MA2 group. The FXIIIa residues that are located in the vicinity of ZED1301 are shown in green. All panels were made in Pymol (DeLano Scientific Inc). PDB code 4KTY.

The kinetic studies involving our MALDI-TOF MS assay reveal that amino acid substitutions at the P-1 to P-3 positions can hinder optimal binding within the FXIIIa active site region S-1 to S-3. For example, changing the P-1 position of α2AP from an acidic E3 to a basic residue R3 causes this peptide to now exhibit the weaker binding properties of S. Aureus FnbA (100–114). A review of the crystal structure of the inhibited complex indicates that FXIIIa residues that are located near the corresponding positions on bound ZED1301 include Y370, N371, and V369. This FXIIIa active site region may have a harder time accommodating the positively charged environment from the R3 guanidinium group at the P-1 position. Interestingly, S. Aureus Fnb A (100–114) has difficulty accepting a Q105S substitution. Somehow the small polar S105 cannot be as well accommodated by the broad FXIIIa S-2 substrate specificity pocket as α2AP (1–15) Q4S. Studies with the TAFI sequence reveal that Q5 at the P-3 instead of the P-2 position produces one of the weakest Km values to date. There may be trouble accepting the more polar TAFI Q5 within the hydrophobic binding area (FXIIIa S-3 to S-6 positions) as opposed to the L5 of ZED1301.

There must be additional subsites on FXIIIa that interact with the P-8 to P-10 substrate positions. α2AP (1–15) and S. Aur FnbA (100–114) could both take advantage of this distant FXIIIa surface to anchor on to and thus help lower the Km value. α2AP (1–15) K12R generated the best Km value to date. The newly reported FXIII-ZED1301 complex extends to the P-6 position [46]. Assessing where to direct the P-8 to P-10 ligand residues on to the transglutaminase surface may however be challenging. Computational studies have been performed on the docking of inhibitors to FXIII, TGase2, TGase3, and microbial transglutaminase [47; 48; 49]. Similar to ZED1301, the synthetic inhibitors have not extended all the way to the P-8 to P-10 substrate positions. There is often more than one putative binding region to direct a ligand to beyond the P-4 position. X-ray crystal structures of FXIIIa bound to longer ligands will be beneficial to the field.

Conclusions

Although several FXIIIa targets have been identified, the characteristics that help produce a good glutamine-containing substrate are not well understood. A MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay was developed to help better decipher how FXIIIa selects these substrates. The knowledge gained may be used later to design more potent substrates and inhibitors of this transglutaminase. The MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay has the advantage of directly monitoring consumption of substrate and formation of product within a single platform. Kinetic analysis using this new assay indicates that the 2QEQ4 (P1, P-1, P-2 positions) residues of α2AP can be well accommodated within the FXIIIa active site. An α2AP K12R substitution further enhances secondary anchoring within the P-8 to P-11 region thus generating the best Km value to date. S. Aureus Fnb A 100–114 was examined for the first time and serves to prove that FXIIIa substrates do benefit from a distant exosite. Kinetic properties for this more basic substrate are, however, not as good as those of α2AP. TAFI is likely such a weak FXIIIa substrate because the second Q is moved from the common P-2 position to the P-3 position that is now at the entrance to the FXIII hydrophobic binding site. Further clues about the amino acid features that govern the substrate specificity of FXIIIa will be obtained from employing our single platform MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 HL68440 and by grant W81XWH from the Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center of the US Army. We are grateful for guidance from D.B. Cleary and T.M. Sabo in the design of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assay for characterizing FXIIIa substrates. We appreciate help in statistical analysis of the data provided by M.C. Yappert. Finally, we thank M.A. Jadhav, R.T. Woofter, and B. Lynch for their critical review of the current project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations Used

human cellular factor XIII, FXIII; activated factor XIII, FXIIIa; α2-antiplasmin, α2AP; fibronectin binding protein A, Fnb A; thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, TAFI; glycine ethylester, GEE; trifluoroacetic acid, TFA; α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, αCHCA; matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry, MALDI-TOF MS; transglutaminase, TGase; FXIIIa inhibitory peptide (Ac-Asp-MA(Michael Acceptor)-Nle-Nle-Leu-Pro-Trp- Pro-OH), ZED1301; Michael Acceptor unit; MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weisel JW. Fibrinogen and fibrin. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:247–299. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lord ST. Fibrinogen and fibrin: scaffold proteins in hemostasis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:236–241. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3280dce58c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muszbek L, Bagoly Z, Bereczky Z, Katona E. The involvement of blood coagulation factor XIII in fibrinolysis and thrombosis. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2008;6:190–205. doi: 10.2174/187152508784871990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muszbek L, Bereczky Z, Bagoly Z, Komaromi I, Katona E. Factor XIII: a coagulation factor with multiple plasmatic and cellular functions. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:931–972. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen LC, Yee VC, Bishop PD, Le Trong I, Teller DC, Stenkamp RE. Transglutaminase factor XIII uses proteinase-like catalytic triad to crosslink macromolecules. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1131–1135. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esposito C, Caputo I. Mammalian transglutaminases. Identification of substrates as a key to physiological function and physiopathological relevance. FEBS J. 2005;272:615–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2004.04476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Standeven KF, Ariens RA, Grant PJ. The molecular physiology and pathology of fibrin structure/function. Blood Rev. 2005;19:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Csosz E, Mesko B, Fesus L. Transdab wiki: the interactive transglutaminase substrate database on web 2.0 surface. Amino Acids. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0121-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonagh J, Fukue H. Determinants of substrate specificity for factor XIII. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1996;22:369–376. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grootjans JJ, Groenen PJ, de Jong WW. Substrate requirements for transglutaminases. Influence of the amino acid residue preceding the amine donor lysine in a native protein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22855–22858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikolajsen CL, Dyrlund TF, Toftgaard Poulsen E, Enghild JJ, Scavenius C. Coagulation Factor XIIIa Substrates in Human Plasma. Identification and Incorporation Into the Clot. J Biol Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.517904. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KN, Birckbichler PJ, Patterson MK., Jr Colorimetric assay of blood coagulation factor XIII in plasma. Clin Chem. 1988;34:906–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slaughter TF, Achyuthan KE, Lai TS, Greenberg CS. A microtiter plate transglutaminase assay utilizing 5-(biotinamido)pentylamine as substrate. Anal Biochem. 1992;205:166–171. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90594-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valnickova Z, Enghild JJ. Human procarboxypeptidase U, or thrombin-activable fibrinolysis inhibitor, is a substrate for transglutaminases. Evidence for transglutaminase-catalyzed cross-linking to fibrin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27220–27224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakata Y, Aoki N. Cross-linking of alpha 2-plasmin inhibitor to fibrin by fibrin-stabilizing factor. J Clin Invest. 1980;65:290–297. doi: 10.1172/JCI109671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madi A, Karpati L, Kovacs A, Muszbek L, Fesus L. High-throughput scintillation proximity assay for transglutaminase activity measurement. Anal Biochem. 2005;343:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skorstengaard K, Halkier T, Hojrup P, Mosher D. Sequence location of a putative transglutaminase cross-linking site in human vitronectin. FEBS Lett. 1990;262:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80208-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sottrup-Jensen L, Stepanik TM, Wierzbicki DM, Jones CM, Lonblad PB, Kristensen T, Mortensen SB, Petersen TE, Magnusson S. The primary structure of alpha 2-macroglobulin and localization of a Factor XIIIa cross-linking site. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1983;421:41–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb18091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karpati L, Penke B, Katona E, Balogh I, Vamosi G, Muszbek L. A modified, optimized kinetic photometric assay for the determination of blood coagulation factor XIII activity in plasma. Clin Chem. 2000;46:1946–1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleary DB, Maurer MC. Characterizing the specificity of activated Factor XIII for glutamine-containing substrate peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:1207–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penzes K, Kover KE, Fazakas F, Haramura G, Muszbek L. Molecular mechanism of the interaction between activated factor XIII and its glutamine donor peptide substrate. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:627–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fickenscher K, Aab A, Stuber W. A photometric assay for blood coagulation factor XIII. Thromb Haemost. 1991;65:535–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardes K, Becker GL, Hammamy MZ, Steinmetzer T. Design, synthesis, and characterization of chromogenic substrates of coagulation factor XIIIa. Anal Biochem. 2012;428:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardes K, Zouhir Hammamy M, Steinmetzer T. Synthesis and characterization of novel fluorogenic substrates of coagulation factor XIII-A. Anal Biochem. 2013;442:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleary DB, Doiphode PG, Sabo TM, Maurer MC. A non-reactive glutamine residue of alpha2-antiplasmin promotes interactions with the factor XIII active site region. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1947–1949. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee KN, Lee CS, Tae WC, Jackson KW, Christiansen VJ, McKee PA. Cross-linking of wild-type and mutant alpha 2-antiplasmins to fibrin by activated factor XIII and by a tissue transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37382–37389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003375200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KN, Jackson KW, Christiansen VJ, Chung KH, McKee PA. A novel plasma proteinase potentiates alpha2-antiplasmin inhibition of fibrin digestion. Blood. 2004;103:3783–3788. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichinose A, Tamaki T, Aoki N. Factor XIII-mediated cross-linking of NH2-terminal peptide of alpha 2-plasmin inhibitor to fibrin. FEBS Lett. 1983;153:369–371. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchie H, Lawrie LC, Crombie PW, Mosesson MW, Booth NA. Cross-linking of plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 and alpha 2-antiplasmin to fibrin(ogen) J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24915–24920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinji H, Yosizawa Y, Tajima A, Iwase T, Sugimoto S, Seki K, Mizunoe Y. Role of fibronectin-binding proteins A and B in in vitro cellular infections and in vivo septic infections by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2215–2223. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00133-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Severina E, Nunez L, Baker S, Matsuka YV. Factor XIIIa mediated attachment of S. aureus fibronectin-binding protein A (FnbA) to fibrin: identification of Gln103 as a major cross-linking site. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1870–1880. doi: 10.1021/bi0521240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuka YV, Anderson ET, Milner-Fish T, Ooi P, Baker S. Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding protein serves as a substrate for coagulation factor XIIIa: evidence for factor XIIIa-catalyzed covalent cross-linking to fibronectin and fibrin. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14643–14652. doi: 10.1021/bi035239h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson ET, Fletcher L, Severin A, Murphy E, Baker SM, Matsuka YV. Identification of factor XIIIA-reactive glutamine acceptor and lysine donor sites within fibronectin-binding protein (FnbA) from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11842–11852. doi: 10.1021/bi049278k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valnickova Z, Thogersen IB, Potempa J, Enghild JJ. The intrinsic enzymatic activity of procarboxypeptidase U (TAFI) does not significantly influence the fibrinolytic rate: reply to a rebuttal. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1336–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valnickova Z, Thogersen IB, Potempa J, Enghild JJ. Thrombin-activable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) zymogen is an active carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3066–3076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bungert D, Heinzle E, Tholey A. Quantitative matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry for the determination of enzyme activities. Anal Biochem. 2004;326:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sleno L, Volmer DA. Assessing the properties of internal standards for quantitative matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of small molecules. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:1517–1524. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jennings LL, Malecki M, Komives EA, Taylor P. Direct analysis of the kinetic profiles of organophosphate-acetylcholinesterase adducts by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11083–11091. doi: 10.1021/bi034756x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bock PE, Panizzi P, Verhamme IM. Exosites in the substrate specificity of blood coagulation reactions. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):81–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gorman JJ, Folk JE. Structural features of glutamine substrates for transglutaminases. Specificities of human plasma factor XIIIa and the guinea pig liver enzyme toward synthetic peptides. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:2712–2715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorman JJ, Folk JE. Structural features of glutamine substrates for transglutaminases. Role of extended interactions in the specificity of human plasma factor XIIIa and of the guinea pig liver enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9007–9010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fraser SR, Booth NA, Mutch NJ. The antifibrinolytic function of factor XIII is exclusively expressed through alpha(2)-antiplasmin cross-linking. Blood. 2011;117:6371–6374. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-333203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yee VC, Pedersen LC, Le Trong I, Bishop PD, Stenkamp RE, Teller DC. Three-dimensional structure of a transglutaminase: human blood coagulation factor XIII. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7296–7300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yee VC, Pedersen LC, Bishop PD, Stenkamp RE, Teller DC. Structural evidence that the activation peptide is not released upon thrombin cleavage of factor XIII. Thromb Res. 1995;78:389–397. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(95)00072-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stieler M, Weber J, Hils M, Kolb P, Heine A, Buchold C, Pasternack R, Klebe G. Structure of Active Coagulation Factor XIII Triggered by Calcium Binding: Basis for the Design of Next-Generation Anticoagulants. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:11930–11934. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwata Y, Tago K, Kiho T, Kogen H, Fujioka T, Otsuka N, Suzuki-Konagai K, Ogita T, Miyamoto S. Conformational analysis and docking study of potent factor XIIIa inhibitors having a cyclopropenone ring. J Mol Graph Model. 2000;18:591–599. 602–604. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahvazi B, Steinert PM. A model for the reaction mechanism of the transglutaminase 3 enzyme. Exp Mol Med. 2003;35:228–242. doi: 10.1038/emm.2003.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tagami U, Shimba N, Nakamura M, Yokoyama K, Suzuki E, Hirokawa T. Substrate specificity of microbial transglutaminase as revealed by three-dimensional docking simulation and mutagenesis. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2009;22:747–752. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]