Abstract

Individual differences in maternal behavior toward, and investment in, offspring can have lasting consequences, particularly among primate taxa characterized by prolonged periods of development over which mothers can exert substantial influence. Given the role of the neuroendocrine system in the expression of behavior, researchers are increasingly interested in understanding the hormonal correlates of maternal behavior. Here, we examined the relationship between maternal behavior and physiological stress levels, as quantified by fecal glucocorticoid metabolite (FGM) concentrations, in lactating chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, at Gombe National Park, Tanzania. After accounting for temporal variation in FGM concentrations, we found that mothers interacted socially (groomed and played) with and nursed their infants more on days when FGM concentrations were elevated compared to days when FGM concentrations were within the range expected given the time of year. However, the proportion of time mothers and infants spent in contact did not differ based on FGM concentrations. These results generally agree with the suggestion that elevated GC concentrations are related to maternal motivation and responsivity to infant cues and are the first evidence of a hormonal correlate of maternal behavior in a wild great ape.

Keywords: Glucocorticoids, Maternal investment, Mother–infant, Stress

Introduction

Conditions experienced during early development can have lasting fitness consequences (Lindstrom 1999). In primates, as in most mammals, early experiences are mediated in large part by the mother (Maestripieri 2009), whose behavior can have a profound impact on offspring survival, development, and subsequent adult behavior (Fairbanks 1996; Maestripieri 2009). Maternal behavior itself is influenced by a variety of factors including ecological conditions; maternal age and rank; and offspring age, sex, and parity (Clutton-Brock 1991; Daly and Wilson 1995; Trivers 1974; Trivers and Willard 1973). Because the mother’s neuroendocrine system also likely plays a role in the expression of maternal behaviors, researchers have become increasingly interested in how variation in maternal hormone concentrations are related to individual differences in maternal behavior (Saltzman and Maestripieri 2011).

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are a class of steroid hormones released at the end of a cascade along the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis during the prototypical vertebrate response to unpredictable or “noxious” stimuli, i.e. stressors (McEwen and Wingfield 2003; Romero 2004). Briefly, GCs, e.g. cortisol in primates, divert energy from storage, thereby providing readily available energetic resources for coping with an acute stressor. However, chronic exposure to stressors and secretion of GCs are associated with a host of adverse health effects including decreased immune function, cardiovascular disease, and reduced reproductive output (Sapolsky 2005; Tamashiro et al. 2005). The concept of allostasis (McEwen and Wingfield 2003; Wingfield 2005) and the related Reactive Scope Model (Romero et al. 2009) provide conceptual frameworks for understanding the seemingly contradictory costs and benefits of GC excretion in response to stressors. Allostasis and the Reactive Scope Model both embrace the underlying concept of “consistency through change,” suggesting that individuals can maintain internal stability (homeostasis) through changes in physiological mediators, e.g., GCs, in response to both predictable stimuli, such as breeding season, and unpredictable stimuli, such as a severe storm or drought (McEwen and Wingfield 2003; Wingfield 2005). Notably, based on this framework what might be considered elevated GC excretion in response to unpredictable stimuli at one time of year or in a given reproductive state may be a predictable level of GC excretion at another time of year or reproductive state. However, extreme or prolonged changes in physiology can lead to pathological problems, such as those negative health outcomes typically associated with chronically elevated GCs.

Pregnancy, birth, and lactation are reproductive states associated with predictable stimuli and accompanied by changes in GC concentrations. In humans and anthropoid primates, GC concentrations increase over the course of pregnancy (humans [Homo sapiens]: Mastorakos and Ilias 2003, chimpanzees [Pan troglodytes] and gorillas [Gorilla gorilla]: Smith et al. 1999) and spike at parturition (bonobos [Pan paniscus]: Behringer et al. 2009; chimpanzees: Murray et al. 2013). Increased GC levels during pregnancy are likely crucial for normal fetal development and timing of parturition (Obel et al. 2005; Sloboda et al. 2005); however, increased circulating GC levels do not necessarily translate into increased reactivity to stressors. Indeed, evidence suggests that reactivity to stressors is inhibited during pregnancy (de Weerth and Buitelaar 2005a,b; de Weerth et al. 2007; Entringer et al. 2009; Mastorakos and Ilias 2003). Nevertheless, research has linked GCs to maternal behavior. GCs in general both modulate behaviors in response to an immediate stressor and prepare individuals for a future challenge (Sapolsky 2000). The specific mechanisms through which GCs relate to maternal behavior remain unclear; however, experimental research on maternal behavior in rodents indicates that GCs may influence maternal arousability and motivation by acting directly on neuronal targets or via interactions with other endocrine or sensory systems (Numan 2007). Previous studies indicate that higher prepartum cortisol levels correspond to increased maternal responsiveness and sensitivity to infant cues, e.g. humans (Fleming et al. 1987, 1997), nonhuman primates (Nguyen et al. 2008), and rodents (Rees et al. 2004). In contrast, where an association has been found, studies of nonhuman primates suggest an inverse relationship between postpartum cortisol levels and quality or quantity of maternal care. In captive baboons (Papio sp.), mothers that maintained less contact with their infants and showed more stress-related behaviors had higher postpartum urinary cortisol levels (Bardi et al. 2004). Levels of maternal rejection also positively correlated with postpartum fecal cortisol levels in captive Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata: Bardi et al. 2003) and with postpartum plasma cortisol levels in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta: Maestripieri et al. 2009). In an experimental study of maternal behavior and stress, female common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) treated with exogenous cortisol carried their infants less than control females (Saltzman and Abbott 2009). The lone study among great apes found that the postpartum stress index, which accounted for interindividual variation in average cortisol concentrations, negatively correlated with the proportion of time mothers spent in ventro-ventral contact with their infants (captive western gorillas: Bahr et al. 1998).

Owing to the logistical challenges of fieldwork, studies of physiological indicators of stress and maternal behavior in primates are typically restricted to captive or free-ranging provisioned populations using techniques that vary in the degree of invasiveness. Wild individuals, however, are exposed to a greater variety of conditions and likely face a wider range of stressors. Interestingly, one study of maternal responsiveness and peripartum GCs in wild baboon mothers (Papio cyanocephalus) found that higher prepartum fecal GC levels predicted greater maternal responsiveness to infant distress calls, whereas postpartum levels did not (Nguyen et al. 2008). The authors attributed this result to the role of GCs in preparing females for the predictable future challenge of infant care.

We here examine the relationship between postpartum fecal glucocorticoid metabolite (FGM) concentrations and maternal behavior in wild east African chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii). Chimpanzees live in multimale, multifemale communities characterized by a fission–fusion social organization where temporary party (subgroup) size and composition vary over the course of the day (Goodall 1986; Nishida 1968). Characteristic of primates, chimpanzees have a prolonged infancy over which maternal behavior can influence offspring. Chimpanzee infants are in almost constant contact with their mothers for the first 4–6 mo of life (Goodall 1986) and remain nutritionally dependent on their mothers until they are weaned between the ages of 3 and 5 yr (Clark 1977; Goodall 1986; Pusey 1983; Rijt-Plooij and Plooij 1987). Older offspring also continue to travel with their mother and younger sibling until adolescence (Pusey 1990).

We investigated how FGM concentrations relate to direct mother–infant interactions among lactating female chimpanzees of the Kasekela community in Gombe National Park, Tanzania. We focused on lactating females as lactation is an energetically demanding state for female chimpanzees and a critical period for offspring survival (Emery Thompson 2013; Emery Thompson et al. 2012). Restricting our analyses to lactating females also avoided confounds due to variation in GC levels across reproductive states in chimpanzees (Emery Thompson et al. 2010) and potential behavioral changes during cycling and pregnancy attributable to future reproductive efforts. Previous studies addressing the socioecological, rather than behavioral, correlates of physiological stress in lactating chimpanzees found that higher urinary cortisol levels were related to low dominance rank, months with greater community-wide rates of female–female aggression, and lower fruit consumption (Kanyawara community, Uganda: Emery Thompson et al. 2010), while higher FGM concentrations in lower ranking females were related to larger party sizes and parties skewed toward more males (Kasekela community, Tanzania: Markham et al. 2014) Interestingly, neither individual rates of aggression nor percent fruit in diet were predictors of FGM concentrations among lactating females in the Kasekela community (Markham et al. 2014).

Here, we specifically examined whether levels of mother–infant social behavior (grooming and playing) or nursing differed based on whether maternal FGM concentrations were elevated vs. within the range expected for a lactating female in this community after controlling for predictable temporal variation in FGM concentrations. We also examined the amount of time mothers and infants spent in contact regardless of whether the mother was actively interacting with the infant. Given evidence of a relationship between postpartum cortisol levels and rejecting maternal behaviors previously reported among nonhuman primates, we predicted mothers would spend less time engaged in social behaviors, nursing, and in contact with their infants on days associated with elevated FGM concentrations. Further, according to parental investment theory, mothers should invest more in the sex whose reproductive success would benefit most from the allocation of additional resources (Clutton-Brock 1991; Hamilton 1967; Trivers and Willard 1973). Given reproductive skew toward dominant males (Wroblewski et al. 2009) and male philopatry, female chimpanzees would be predicted to invest more in male offspring than in female offspring. Therefore, we predicted that differences in maternal behavior based on FGM concentrations would be more pronounced in females than in males, suggesting biased investment in males in stressful situations. Using a 2-day sampling protocol, we paired behavioral observations on the first day with fecal samples on the second day. These day 2 fecal samples reflect day 1 glucocorticoid concentrations (Murray et al. 2013). This protocol allowed us to examine closely the relationship between FGM concentration and maternal behavior in a wild chimpanzee community.

Methods

Study Site and Subjects

Researchers collected behavioral and physiological data for this study between January 2009 and August 2013 as part of a long-term study of maternal behavior and infant development in the Kasekela community of Gombe National Park, Tanzania. This community has been under continuous observation since 1960 and during the course of this study ranged in size from 57 to 62 individuals.

This study focused on 12 lactating females with infants >6 mo of age but <4 yr of age (Table I). We categorized females as lactating between the birth of an infant and the earliest date of the following: the infant’s death, the conception of the female’s next offspring, or the infant’s fourth birthday as weaning typically occurs between 3 and 5 yr of age (Clark 1977; Goodall 1986; Pusey 1983; Rijt-Plooij and Plooij 1987). Because of the spike in circulating glucocorticoids at parturition, gradual decline toward prepregnancy levels, and suppression of the maternal HPA axis immediately postpartum (Mastorakos and Ilias 2003; Nyberg 2013), we did not include data from mothers with very young infants. Research in humans suggests that HPA activity returns to normal after 12 wk postpartum (ca. 3 mo) (Magiakou et al. 1997); therefore we conservatively excluded data from mothers with infants <6 mo of age. In chimpanzees, the first 6 mo postpartum may also be behaviorally distinct because chimpanzee infants are in almost constant contact with their mothers (Goodall 1986) and the energetic burden of lactation for mothers is highest (Emery Thompson et al. 2012).

Table I.

Demographic and sample size information for mothers and their infants from the Kasekela chimpanzee community from January 2009 to August 2013 included in behavioral analyses

| Mother | Infant | Infant sex |

Infant age range (yr) |

Total observation time (h) |

Number of follows |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAH | BAS | F | 1.34–2.93 | 43.92 | 4 |

| BAH | BRZ | M | 3.75–3.75 | 6.33 | 1 |

| DL | DUK | M | 0.52–1.29 | 65.97 | 6 |

| EZA | ERI | M | 2.89–3.05 | 34.62 | 4 |

| FN | FAD | F | 1.73–1.91 | 16.70 | 2 |

| FN | FFT | M | 0.98–2.47 | 137.15 | 14 |

| GA | GGL | M | 1.00–3.92 | 234.58 | 24 |

| GLD | GLA | F | 0.69–1.93 | 116.15 | 11 |

| GLI | GOS | F | 0.66–1.13 | 43.25 | 4 |

| GM | GIZ | M | 0.87–3.90 | 179.92 | 18 |

| NUR | NYO | M | 0.93–2.81 | 108.72 | 11 |

| SA | SIR | M | 2.68–3.91 | 62.68 | 9 |

| SI | SAF | F | 0.65–2.03 | 50.07 | 7 |

| TG | TAB | F | 2.74–3.96 | 39.43 | 5 |

| TG | TAR | F | 0.70–0.73 | 21.20 | 2 |

| Totals | 1169.7 | 122 |

Data Collection

Each observation day, researchers followed a focal mother, infant, and next oldest sibling when present, i.e., a “family group,” and recorded each focal’s behavior, social partner when relevant, and distance between family group members at 1-min point samples (Altmann 1974; Goodall 1986; see Lonsdorf et al. 2014a for more detailed ethogram) for up to ca. 12 h (night nest-to-night nest). Researchers also recorded behavioral events such as vocalizations and sexual behaviors ad libitum throughout the follow and conducted party composition scans throughout each follow at 5-min intervals until 2011 and 15-min intervals thereafter. During the period of this study, research staff followed the same focal subjects 2 days in a row and collected day 2 fecal samples for hormone quantification. In chimpanzees, raised glucocorticoid metabolites manifest in feces 12–24 h later (Murray et al. 2013). Thus, this 2-day protocol allows behavioral data recorded on day 1 to be paired with FGM concentrations from day 2. We set a minimum threshold of 5 h of day 1 behavioral data for inclusion in these analyses (Npaired samples = 122, Table I). To control for possible diurnal patterns in FGM concentrations (Murray et al. 2013), we included only morning fecal samples collected before 12:00 h in these analyses. If more than one fecal sample was collected on the same mother the same morning, the FGM concentrations were averaged.

Metrics

We focused on direct measures of mother–infant interactions, including social interactions (mother grooming or playing with her infant; excludes mother being groomed by her infant), and nursing (measured by suckling, or time spent on the nipple; see Lonsdorf et al. 2014a for detailed ethogram). We also investigated time mothers and infants spent in contact with each other, e.g., contact during rest or when offspring are carried by their mother during travel, regardless of whether they were actively engaged with one another in one of the social interactions described previously. Behaviors were measured as the proportion of a follow spent engaged in that behavior. For example, we calculated the proportion of time a mother spent nursing her infant as the number of 1-min point samples on which the infant was nursing divided by the total number of 1-min point samples for that follow. Minutes in which the mother or infant behavior was uncertain were excluded. Proportion of time in contact was the number of 1-min point samples the mother and infant were observed in contact over the total number 1-min point sample distance observations for that follow.

Physiological Data

We noninvasively collected fecal samples on day 2 to partner with day 1 behavioral data. Throughout the study period, researchers also opportunistically collected maternal fecal samples not paired with behavioral data and we used these samples used to quantify expected FGM concentrations. All samples were stored in our field lab freezer until extraction. Our extraction method circumvents many of the challenges of delayed extraction, inadvertent extraction into fixed samples, and difficulty in shipment. This method has been biologically and physiologically validated (Murray et al., 2013). In short, we weighed 0.50 g (± 0.02 g) wet feces. We then added 5.0 ml of 90% ethanol into 16–100 mm tubes and hand-shook the tubes for 30 s. The tubes were then rotated for 2 h, and centrifuged for 20 min at 1500 rpm. We stored 1-ml aliquots of the resultant supernatant in another set of labeled 12–75 mm tubes. The aliquots were allowed to dry in a sealed case with desiccant to prevent bacterial contamination and degradation. Once dry, we capped and shipped the samples to the Santymire Lab (Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, IL) for analyses (see Murray et al. 2013 for enzyme immunoassay specifics and validation; intraassay variation was <10% and interassay variation was <20%).

Statistical Analyses

To control for temporal fluctuations in FGM concentrations, we created time of year-adjusted FGM concentration categories. Wet/dry seasonal variation in glucocorticoid and other hormone concentrations is documented in a number of primate species, including chimpanzees, e.g., baboons (Gesquiere et al. 2008), chimpanzees (Muller and Wrangham 2004), and bonobos (Surbeck et al. 2012). To control for such periodic fluctuations we calculated the FGM concentration expected for a lactating female in this community on any given day of the year. Using ordinary least squares regression, we regressed log10 transformed FGM concentrations from morning fecal samples opportunistically collected from lactating females during the study period, but not paired with behavioral data (Nfemales = 12; Nsamples = 629) against two sine-plus-cosine functions (Shumway and Stoffer 2011) with annual and semiannual periodicities. We included the semiannual term to allow for two peaks in FGM concentration over the course of the year since each calendar year begins (January–April) and ends (November–December) in the wet season (Goodall 1986; Pusey et al. 2005), and preliminary analyses indicated that Kasekela female FGM concentrations are higher during wet season months as compared to dry season months (unpubl. data). The model incorporating both the annual and semiannual periods explained the temporal variability in lactating female FGM concentrations better than annual (likelihood ratio test: , P < 0.001) or semiannual alone (likelihood ratio test: , P < 0.001). Given the naturally occurring variation in GC excretion, we were specifically interested in FGM concentrations much larger than expected, as they are more likely to relate to behavior. Therefore, using the model described in the preceding text, we calculated the 50% prediction interval. That is, given the model parameters, the range in which there is a 50% chance that a new response will fall. Behavioral data from each day 1 that was paired with a day 2 FGM concentration that fell above the upper bound of the 50% prediction interval were categorized as having been collected when FGM concentrations were elevated (N = 33) as the concentrations were higher than predicted for a lactating female in the Kasekela community given the time of year. Those days of behavioral data paired with FGM concentrations that fell below the upper bound of the 50% prediction interval were categorized as within the expected range of FGM concentrations for a lactating female in the Kasekela community given the time of year (N = 89) (Fig. 1). Infant age in days was not a significant predictor of variation in lactating female FGM concentrations (F1, 488 = 1.08, P = 0.23) and thus not included in the model. In addition, including a random effect of female ID did not significantly improve model fit (likelihood ratio test: , P = 0.80) and explained just 0.5% of the variation, thus this individual was not included in the model predicting temporal variation in FGM concentrations.

Fig. 1.

Plot of fecal glucocorticoid metabolite (FGM) concentration categorization based on the expected value for a lactating female chimpanzee in the Kasekela community on a given day of the year (January 2009–August 2013). The solid line represents the predicted relationship between log10 FGM concentrations and day of the year based on a linear regression using FGM concentrations from unpaired samples (Nsamples = 629; Nfemales = 12; see Methods for details). The dashed line represents the 50% prediction interval from that model. Each point represents a day 2 log10 FGM concentration that was paired with day 1 behavioral data (Npaired samples= 122; Nfemales = 12). FGM concentrations that fell above the 50% prediction interval were categorized as elevated (triangles), while those that fell at or below the 50% prediction interval (shaded region) were categorized as within the expected range (circles).

To investigate differences in maternal behavior based on FGM categories after adjusting for time of year, we fit generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with proportion of observation time engaged in each behavior as the response variable and FGM concentration category, infant age in days, sex of the infant, average daily adult party size, and the interaction of FGM category and infant sex as fixed explanatory variables. Average daily adult party size was calculated as the average number of adults (≥12 yr of age) present in party composition scans across a given day and has been shown to correlate with FGM concentrations for low-ranking lactating females in the study population (Markham et al. 2014). We also included two random effects: month to control for possible differences in behavior due to time of the year and maternal ID to control for repeated and uneven sampling and month of the year. All GLMMs were fit using a Gaussian error distribution and an identity link function. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed by visual inspection of plots of residuals against predicted values. Proportion response variables were arcsine-square root transformed to meet these assumptions. All analyses were conducted in R (version 3.0.3, R Core Development Team 2014) using the lme4 (Bates et al. 2014) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al. 2014) packages for GLMMs.

Ethical Note

This research was noninvasive, complied with the laws of Tanzania, and was approved by The Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology, Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, and Tanzania National Parks Authority.

Results

Temporal Variation in Lactating Female FGM Concentrations

Time of year significantly predicted lactating female FGM concentrations (overall model: F4, 485 = 27.10, P < 0.001, R2 = 0.18; sine annual: F1, 485 = 28.12, P < 0.001; cosine annual: F1, 485 = 46.02, P < 0.001; sine semiannual: F1, 485 = 0.14, 6 P = 0.702; cosine semiannual: F1, 485 = 34.14, P < 0.001; Fig. 1).

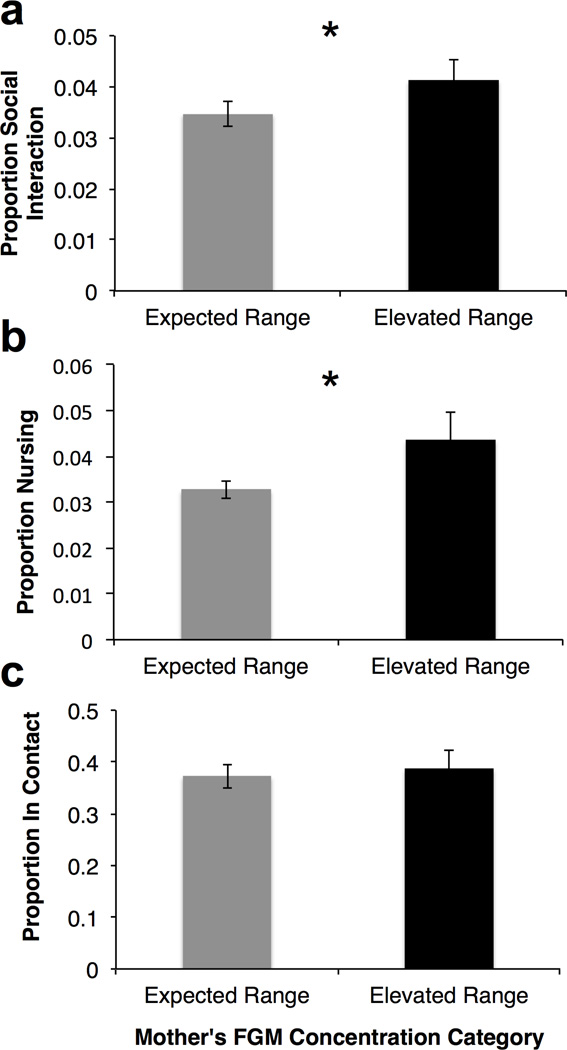

Social Interactions

Mothers spent a greater proportion of time socially interacting with their infants on days corresponding to elevated FGM concentrations as compared to days within the expected range (F1, 121.26 = 5.00, P = 0.027; Fig. 2a) and with females as compared to males (mean ± SE proportion males: 0.031 ± 0.002; females: 0.050 ± 0.004; F1, 119.14 = 12.17, P < 0.001). Infant age in days (F1, 114..15 = 0.270, P = 0.604), the interaction of FGM category and infant sex (F1, 121.96 = 0.559, P = 0.456), and average adult party size (F1, 86.80 = 0.484, P = 0.488) were not significant predictors of the proportion of time mothers socially interacted with their infants.

Fig. 2.

Mean ± SE proportion of follow time mothers in the Kasekela chimpanzee community from January 2009 to August 2013 spent (a) socially interacting (grooming or playing), (b) nursing, or (c) in contact with their infants by maternal FGM concentration category. Nexpected = 89; Nelevated=33. *P < 0.05.

Nursing

Mothers also spent a greater proportion of time nursing their infants on days corresponding to elevated FGM concentrations as compared to days with in the expected range (F1, 112.51 = 4.51, P = 0.036; Fig. 2b). There was no main effect of infant sex (F1, 39.49 = 0.001, P = 0.970) or average adult party size (F1, 116.35 = 0.021, P = 0.885), but proportion of time nursing did increase with infant age (F1, 121.82 = 4.40, P = 0.038), potentially indicative of weaning conflict at later ages rather than increased nutritional investment by mothers. The interaction of FGM category and infant sex was also not significant (F1, 111.67 = 0.014, P = 0.908).

In Contact

Proportion of time mothers and infants spent in contact with each other did not differ by FGM category (F1, 113.60 = 0.220, P = 0.640; Fig. 2c), infant sex (F1, 26.41 = 0.014, P = 0.907), average adult party size (F1, 62.506 = 0.504, P = 0.485), or the interaction of FGM category and infant sex (F1, 109.72 = 0.159, P = 0.907), but did significantly decrease with increasing infant age (F1, 105.16 = 121.05, P < 0.001).

Discussion

In this first study of the hormonal correlates of maternal behavior in wild chimpanzees, we found that elevated maternal FGM concentrations were associated with more time actively engaged in mother–infant social interactions, but not time in contact. Mothers also interacted with daughters more than sons, which is not surprising given evidence that male chimpanzee infants are socially precocious relative to female infants and thus more likely to be interacting with nonmothers (Lonsdorf et al. 2014a,b; Murray et al. 2014). Mothers also nursed their offspring more on days associated with elevated FGM concentrations as compared to days associated with FGM concentrations within the range expected for the time of year. These results differ from those nonhuman, primarily captive, primate studies that found higher postpartum cortisol levels corresponded to greater maternal rejection and less time in contact (Bahr et al. 1998; Bardi et al. 2003, 2004; Maestripieri et al. 2009; Saltzman and Abbott 2009). Instead, our results more generally agree with the body of literature, particularly in humans and rodents, that suggests that elevated GC concentrations are related to maternal responsivity to infant cues (Fleming et al., 1987, 1997; Krpan et al. 2005; Nguyen et al., 2008; Rees et al. 2004).

Given the male reproductive skew and male philopatry of chimpanzees, chimpanzee mothers should theoretically be predicted to invest more in males than females. In support of this prediction, a study of west African chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) found that when females were dominant, they invested more in sons, as determined by longer interbirth intervals (IBI) (Boesch 1997), while a study of east African chimpanzees at Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania reported that IBIs tended to be longer after the birth of a son than the birth of a daughter (Nishida et al. 2003). However, neither a main effect of infant sex nor the interaction of sex and dominance rank on IBI length was observed among Gombe chimpanzees (Jones et al. 2010). In other primates, milk energy density and yield are known to differ based on infant sex (Hinde 2009) and cortisol concentrations in milk are related to temperament in rhesus macaques (Sullivan and Hinde 2011). Our results indicate that mothers nursed infants more on elevated FGM days as compared to days on which FGM concentrations were within the expected range, yet we did not find any significant interaction between FGM category and infant sex. However, we cannot evaluate the quality or quantity of milk transferred from mother to offspring of either sex on elevated versus expected FGM days; thus the nutritional investment and consequences of cortisol in the mother’s milk are unclear. Another potential consideration is that the act of nursing itself may influence maternal GC levels. Studies in humans and rodents indicate that the suckling stimulus of infants elicits the release of oxytocin in the mother, which attenuates maternal cortisol concentrations (Carter et al. 2001; Windle et al. 2004). Given the flexibility observed here, more detailed studies are needed to understand the relationship between maternal physiological stress levels and this fundamental mammalian behavior.

Our results also beg the question: Why do mothers spend more time engaged in social interactions with their infants on elevated FGM days? Mothers may be more restless or anxious when experiencing higher than expected FGM concentrations. Self-directed behaviors, such as self-scratching, are often used as behavioral indicators of anxiety or stress (Troisi 2002) and mothers may direct their behavior toward their infants rather than themselves. Intriguingly, affiliative maternal behaviors may buffer infants against the presence of stressors. In mice, high levels of maternal licking of pups are associated lower reactivity to pain (Walker 2010) while in humans, quality of maternal care and maternal touch is positively related to cortisol recovery from a mild stressor (Albers et al. 2008; Feldman et al. 2010). Both observational and experimental evidence indicates that the neuropeptide oxytocin suppresses HPA axis function (Hennessy et al. 2009; Smith and Wang 2012) and that oxytocin concentrations are related to affiliative behaviors such as nursing and soothing touch. Lending support to this argument, the occurrence of social grooming between both kin and nonkin social bond partners was associated with increased urinary oxytocin levels in wild chimpanzees (Crockford et al. 2013). However, given the observational nature of these data, we cannot determine the direction of any relationship between FGM concentrations and maternal behavior. In humans, for example, levels of postpartum depression are related to difficult infant temperament (Cutrona and Troutman 1986). Therefore, it is also possible that increased interaction with her infant is stressful for the mother, particularly if the infant is demanding attention or distracting the mother from other tasks.

Understanding the relationship between maternal behavior and reactivity to stressors is crucial given the potential consequences for offspring behavior and development. In humans, stressors such as poverty, intimate partner violence, and lack of social support are associated with incidence of child abuse and neglect (Adamakos et al. 1986; Taylor et al. 2009). This pattern is also observed in nonhuman primates, including pigtail macaques where maternal abuse is often preceded by social stressors (Maestripieri 1994; Maestripieri and Carroll 1998). In terms of stress reactivity, juvenile savannah baboons (Papio sp.) whose mothers had displayed more stress-related behaviors had higher cortisol levels and more active reactions to a stressful situation (Bardi et al. 2005). Mothering style can also influence an offspring’s own parenting behavior (Berman 1990; Fairbanks and McGuire 1988; Maestripieri 2007), including the likelihood of infant abuse (Maestripieri 2005). However, not all seemingly negative maternal behaviors are necessarily harmful and in some cases greater maternal attention may be costly. The resilience and stress inoculation hypotheses suggest that exposure to mild stressors early in life may facilitate development of arousal regulation and allow individuals to better manage future stressors (Fairbanks and Hinde 2013; Lyons et al. 2009). For example, offspring of more rejecting mothers become independent at an earlier age (Bardi and Huffman 2002; Schino et al. 2001) and cope better with social stressors as adults (Schino et al. 2001), while offspring of more protective, less permissive mothers are more timid in novel situations (Fairbanks and McGuire 1988).

In this study we found that elevated FGM concentrations were associated with greater time spent engaged in maternal behaviors including mother–infant social interactions and nursing. These results contrast with studies in other species that have reported a negative relationship between maternal behaviors and measures of stress (Bardi et al. 2003; Maestripieri 1994; Maestripieri and Carroll 1998; Maestripieri et al. 2009). It is possible that the natural and relatively routine elevations in FGM concentration examined here are not extreme enough or sustained long enough to be associated with the withholding of nurturing behavior or outright abusive behavior observed in other primate studies (Bahr et al. 1998; Saltzman and Abbott 2009). Regardless, these results align with studies suggesting the short-term adaptive value of maternal GCs and their role in mediating maternal arousal and motivation (Fleming et al. 1987; Maestripieri 2011). Greater levels of mother–infant interaction when FGM concentrations are elevated may be particularly beneficial if the behavior buffers offspring against a perceived stressor. Although future studies of this chimpanzee community will investigate how maternal behavior and stress reactivity relate to infant outcomes and how factors such as maternal rank and experience might modulate the relationship, the broad patterns uncovered here provide the first evidence for stress hormone concentrations as a factor associated with variation in maternal behavior in a wild great ape.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tanzania National Parks, the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, and the Tanzanian Commission for Science and Technology for granting us permission to work in Gombe National Park. We also thank the Jane Goodall Institute for funding long-term research and the Gombe Stream Research Centre staff including J. Mazogo, M. Yahaya, S. Mpindu, B. Daniel, and C. Mpongo for maintaining data collection. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R00HD057992), the Leo S. Guthman Foundation, the National Geographic Society, and grants to M. Heintz (NSFGRF, Leakey Foundation, Werner-Gren, Foundation, and Field Museum African Council). Finally, we thank V. Fiorentio, S. Reji, and K. Anderson for data management; D. Armstrong for lab assistance; all of the assistants who participated in data entry; C. Markham for helpful discussions; and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Margaret A. Stanton, Email: mastanton@gwu.edu, Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052.

Matthew R. Heintz, Department of Conservation and Science, Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, Illinois 60614; and Committee on Evolutionary Biology, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637

Elizabeth V. Lonsdorf, Department of Psychology, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania 17604

Rachel M. Santymire, Department of Conservation and Science, Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, Illinois 60614; and Committee on Evolutionary Biology, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637

Iddi Lipende, Gombe Stream Research Centre, Gombe, Tanzania.

Carson M. Murray, Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052

References

- Adamakos H, Ryan K, Ullman DG, Pascoe J, Diaz R, Chessare J. Maternal social support as a predictor of mother-child stress and stimulation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1986;10(4):463–470. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(86)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers EM, Riksen-Walraven JM, Sweep FCGJ, de Weerth C. Maternal behavior predicts infant cortisol recovery from a mild everyday stressor. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann J. Observational study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behaviour. 1974;49:227–266. doi: 10.1163/156853974x00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr NI, Pryce CR, Döbeli M, Martin RD. Evidence from urinary cortisol that maternal behavior is related to stress in gorillas. Physiology & Behavior. 1998;64(4):429–437. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardi M, Bode AE, Ramirez SM, Brent LY. Maternal care and development of stress responses in baboons. American Journal of Primatology. 2005;66(3):263–278. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardi M, French JA, Ramirez SM, Brent L. The role of the endocrine system in baboon maternal behavior. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55(7):724–732. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardi M, Huffman MA. Effects of maternal style on infant behavior in Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) Developmental Psychobiology. 2002;41(4):364–372. doi: 10.1002/dev.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardi M, Shimizu K, Barrett GM, Borgognini-Tarli SM, Huffman MA. Peripartum cortisol levels and mother-infant interactions in Japanese macaques. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2003;120(3):298–304. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker BM, Walker S. Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Behringer V, Clauss W, Hachenburger K, Kuchar A, Möstl E, Selzer D. Effect of giving birth on the cortisol level in a bonobo groups’ (Pan paniscus) saliva. Primates. 2009;50(2):190–193. doi: 10.1007/s10329-008-0121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman CM. Consistency in maternal behavior within families of free-ranging rhesus monkeys: An extension of the concept of maternal style. American Journal of Primatology. 1990;22(3):159–169. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350220303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesch C. Evidence for dominant wild female chimpanzees investing more in sons. Animal Behaviour. 1997;54:811–815. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1996.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Altemus M, Chrousos GP. Neuroendocrine and emotional changes in the post-partum period. Progress in Brain Research. 2001;133:241–249. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(01)33018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C. A preliminary report on weaning among chimpanzees of the Gombe National Park, Tanzania. In: Chevalier-Skolinkoff S, Poirer F, editors. Primate biosocial development: Biological, social and ecological determinants. New York: Garland; 1977. pp. 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock TH. The evolution of parental care. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Crockford C, Wittig RM, Langergraber K, Ziegler TE, Zuberbühler K, Deschner T. Urinary oxytocin and social bonding in related and unrelated wild chimpanzees. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2013;280:20122765. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona C, Troutman B. Social support, infant temperment, and parenting self-efficacy: A mediational model of postpartum depression. Child Development. 1986;57:1507–1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Wilson M. Discriminative parental solicitude and the relevance of evolutionary models to the analysis of motivational systems. The Cognitive Neurosciences. 1995:1269–1286. [Google Scholar]

- de Weerth C, Buitelaar J. Cortisol awakening response in pregnant women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005a;30(9):902–907. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weerth C, Buitelaar J. Physiological stress reactivity in human pregnancy–a review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005b;29(2):295–312. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weerth C, Wiled C, Jansen L, Buitelaar J. Cardiovascular and cortisol responses to a psychological stressor during pregnancy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2007:1–12. doi: 10.1080/00016340701547442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery Thompson M. Reproductive ecology of female chimpanzees. American Journal of Primatology. 2013;75(3):222–237. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery Thompson M, Muller MN, Kahlenberg SM, Wrangham RW. Dynamics of social and energetic stress in wild female chimpanzees. Hormones and Behavior. 2010;58(3):440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery Thompson M, Muller MN, Wrangham RW. The energetics of lactation and the return to fecundity in wild chimpanzees. Behavioral Ecology. 2012;23(6):1234–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Buss C, Shirtcliff E, Cammack A, Yim I, Chicz-Demet A, et al. Attenuation of maternal psychophysiological stress responses and the maternal cortisol awakening response over the course of human pregnancy. Stress. 2009;13(3):258–268. doi: 10.3109/10253890903349501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks L. Individual differences in maternal style: Causes and consequences for mothers and offspring. Advances in the Study of Behavior. 1996;2(1969):579–611. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks LA, Hinde K. Behavioral response of mothers and infants to variation in maternal condition: Adaptation, compensation, and resilience. In: Clancy KBH, Hinde K, Rutherford JN, editors. Building babies. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013. pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks L, McGuire M. Long-term effects of early mothering behavior on responsiveness to the environment in vervet monkeys. Developmental Psychobiology. 1988;21(7):711–724. doi: 10.1002/dev.420210708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Singer M, Zagoory O. Touch attenuates infants’ physiological reactivity to stress. Developmental Science. 2010;13(2):271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AS, Ruble D, Krieger H, Wong PY. Hormonal and experiential correlates of maternal responsiveness during pregnancy and the puerperium in human mothers. Hormones and Behavior. 1997;31(2):145–158. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AS, Steiner M, Anderson V. Hormonal and attitudinal correlates of maternal behaviour during the early post-partum period in first-time mothers. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1987;5(4):193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gesquiere LR, Khan M, Shek L, Wango TL, Emmanuel O, Alberts SC, Altmann J. Coping with a challenging environment: Effects of seasonal variability and reproductive status on glucocorticoid concentrations of female baboons (Papio cynocephalus) Hormones and Behavior. 2008;54(3):410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J. The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WD. Extraordinary sex ratios. Science. 1967;156:477–488. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3774.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy MB, Kaiser S, Sachser N. Social buffering of the stress response: Diversity, mechanisms, and functions. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2009;30(4):470–482. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde K. Richer milk for sons but more milk for daughters: Sex-biased investment during lactation varies with maternal life history in rhesus macaques. American Journal of Human Biology. 2009;21(4):512–519. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JH, Wilson ML, Murray C, Pusey AE. Phenotypic quality influences fertility in Gombe chimpanzees. The Journal of Animal Ecology. 2010;79(6):1262–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krpan KM, Coombs R, Zinga D, Steiner M, Fleming AS. Experiential and hormonal correlates of maternal behavior in teen and adult mothers. Hormones and Behavior. 2005;47(1):112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Bruun Brockhoff P, Haubo Bojesen Christensen R. lmerTest: Tests for random and fixed effects for linear mixed effect models (lmer objects of lme4 package) 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom J. Early development and fitness in birds and mammals. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1999;14(9):343–348. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdorf EV, Anderson KE, Stanton MA, Shender M, Heintz MR, Goodall J, Murray CM. Boys will be boys: Sex differences in wild infant chimpanzee social interactions. Animal Behaviour. 2014b;88:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdorf EV, Markham AC, Heintz MR, Anderson KE, Ciuk DJ, Goodall J, Murray CM. Sex differences in wild chimpanzee behavior emerge during infancy. PloS One. 2014a;9(6):e99099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons DM, Parker KJ, Katz M, Schatzberg AF. Developmental cascades linking stress inoculation, arousal regulation, and resilience. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;3:1–9. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.032.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D. Infant abuse associated with psychosocial stress in a group-living pigtail macaque (Macaca nemestrina) mother. American Journal of Primatology. 1994;32(1):41–49. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350320105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D. Early experience affects the intergenerational transmission of infant abuse in rhesus monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2005;102(27):9726–9729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504122102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D. Intergenerational transmission of maternal behavior in rhesus macaques and its underlying mechanisms. Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49(2):165–171. doi: 10.1002/dev.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D. Maternal influences on offspring growth, reproduction, and behavior in Primates. In: Maestripieri D, Mateo JM, editors. Maternal effects in mammals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2009. pp. 256–291. [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D. Emotions, stress, and maternal motivation in primates. American Journal of Primatology. 2011;73(6):516–529. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D, Carroll K. Risk factors for infant abuse and neglect in group-living rhesus monkeys. Psychological Science. 1998;9(2):143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D, Hoffman CL, Anderson GM, Carter CS, Higley JD. Mother-infant interactions in free-ranging rhesus macaques: Relationships between physiological and behavioral variables. Physiology & Behavior. 2009;96(4–5):613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiakou M, Mastorakos G, Webster E, Chrousos G. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the female reproductive system. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;816:42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham AC, Santymire RM, Lonsdorf EV, Heintz MR, Lipende I, Murray CM. Rank effects on social stress in lactating chimpanzees. Animal Behaviour. 2014;87:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastorakos G, Ilias I. Maternal and fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axes during pregnancy and postpartum. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;997(1):136–149. doi: 10.1196/annals.1290.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Wingfield JC. The concept of allostasis in biology and biomedicine. Hormones and Behavior. 2003;43(1):2–15. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller MN, Wrangham RW. Dominance, cortisol and stress in wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2004;55(4):332–340. doi: 10.1007/s00265-020-02872-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CM, Heintz MR, Lonsdorf EV, Parr LA, Santymire RM. Validation of a field technique and characterization of fecal glucocorticoid metabolite analysis in wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) American Journal of Primatology. 2013;8(1):57–64. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CM, Lonsdorf EV, Stanton MA, Wellens KR, Miller JA, Goodall J, Pusey AE. Social exposure in wild chimpanzees: Mothers with sons are more gregarious than mothers with daughters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2014;111(51):18189–18194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409507111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen N, Gesquiere LR, Wango EO, Alberts SC, Altmann J. Late pregnancy glucocorticoid levels predict responsiveness in wild baboon mothers (Papio cynocephalus) Animal Behaviour. 2008;75(5):1747–1756. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T. The social group of wild chimpanzees in the Mahali mountains. Primates. 1968;9:167–224. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Corp N, Hamai M, Hasegawa T, Hiraiwa-Hasegawa M, Hosaka K, et al. Demography, female life history, and reproductive profiles among the chimpanzees of Mahale. American Journal of Primatology. 2003;59(3):99–121. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan M. Motivational systems and the neural circuitry of maternal behavior in the rat. Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49:165–171. doi: 10.1002/dev.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg CH. Building babies: Primate development in proximate and ultimate perspective. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013. Navigating transitions in hypothalamic– pituitary–adrenal function from pregnancy through lactation: Implications for maternal health and infant brain development; pp. 133–154. Developments in primatology: Progress and Prospects. [Google Scholar]

- Obel C, Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ, Olsen J, Levine S. Stress and salivary cortisol during pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(7):647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusey A. Behavioural changes at adolescence in chimpanzees. Behaviour. 1990;115(3):203–246. [Google Scholar]

- Pusey AE. Mother-offspring relationships in chimpanzees after weaning. Animal Behaviour. 1983;31(2):363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Rees SL, Panesar S, Steiner M, Fleming AS. The effects of adrenalectomy and corticosterone replacement on maternal behavior in the postpartum rat. Hormones and Behavior. 2004;46(4):411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijt-Plooij H, van de, Plooij F. Growing independence, conflict and learning in mother-infant relations in free-ranging chimpanzees. Behaviour. 1987;101(1):1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Romero LM. Physiological stress in ecology: Lessons from biomedical research. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2004;19(5):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero LM, Dickens MJ, Cyr NE. The Reactive Scope Model – A new model integrating homeostasis, allostasis, and stress. Hormones and Behavior. 2009;55(3):375–389. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman W, Abbott D. Effects of elevated circulating cortisol concentrations on maternal behavior in common marmoset monkeys (Callithrix jacchus) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(8):1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman W, Maestripieri D. The neuroendocrinology of primate maternal behavior. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2011;35(5):1192–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science. 2005;308(5722):648–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1106477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and perparative actions. Endocrine Reviews. 2000;21(1):55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schino G, Speranza L, Troisi A. Early maternal rejection and later social anxiety in juvenile and adult Japanese macaques. Developmental Psychobiology. 2001;38:186–190. doi: 10.1002/dev.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway RH, Stoffer DS. Time series analyses and its applications. 3rd ed. London: Springer Science+Business Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda D, Moss TJ, Newnham J, Challis JR. Fetal HPA activation, preterm birth, and postnatal programming. In: Power M, Schulkin J, editors. Birth, distress, and disease: Placenta-brain interactions. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Wang Z. Salubrious effects of oxytocin on social stress-induced deficits. Hormones and Behavior. 2012;61(3):320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Wickings EJ, Bowman ME, Belleoud A, Dubreuil G, Davies JJ, Madsen G. Corticotropin-releasing hormone in chimpanzee and gorilla pregnancies. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84(8):2820–2825. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan E, Hinde K. Cortisol concentrations in the milk of rhesus monkey mothers are associated with confident temperament in sons, but not daughters. Developmental Psychobiology. 2011;53(1):96–104. doi: 10.1002/dev.20483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surbeck M, Deschner T, Weltring A, Hohmann G. Social correlates of variation in urinary cortisol in wild male bonobos (Pan paniscus) Hormones and Behavior. 2012;62(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamashiro KLK, Nguyen MMN, Sakai RR. Social stress: From rodents to primates. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2005;26(1):27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Guterman NB, Lee SJ, Rathouz PJ. Intimate partner violence, maternal stress, nativity, and risk for maternal maltreatment of young children. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(1):175–183. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers R. Parent-offspring conflict. Americal Zoologist. 1974;14:249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Trivers R, Willard D. Natural selection of parental ability to vary the sex ratio of offspring. Science. 1973;179:90–92. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4068.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi A. Displacement activities as a behavioral measure of stress in nonhuman primates and human subjects. Stress. 2002;5(1):47–54. doi: 10.1080/102538902900012378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker CD. Maternal touch and feed as critical regulators of behavioral and stress responses in the offspring. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52(7):638–650. doi: 10.1002/dev.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle RJ, Kershaw YM, Shanks N, Wood SA, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. Oxytocin attenuates stress-induced c-fos mRNA expression in specific forebrain regions associated with modulation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal activity. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(12):2974–2982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield JC. The concept of allostasis: Coping with a capricious environment. Journal of Mammalogy. 2005;86(2):248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski EE, Murray CM, Keele BF, Schumacher-Stankey JC, Hahn BH, Pusey AE. Male dominance rank and reproductive success in chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii. Animal Behaviour. 2009;77(4):873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]