The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education's (ACGME) new accreditation system has introduced a significantly different world of assessment with its language of milestones and centralized oversight of trainee performance by Clinical Competency Committees (CCCs). Just as the shift to competency-based education and assessment required a culture shift for graduate medical education programs across the United States,1 so, too, does the shift to using CCCs to determine trainee progression on milestones. In this article, we offer our perspectives on the role of the CCC and discuss challenges and opportunities for graduate medical education programs as they enter this new world of assessment.

It's Not Your Same Old Residency Evaluation Committee

CCCs, as outlined by the ACGME, will not function in the same way that many of the old residency evaluation committees did. Simply identifying failing residents or fellows and discussing remediation plans will not be enough. Performance appraisals of progress will need to be conducted for each trainee—including high performers—on each milestone. Professional judgment, contributed by individual CCC members, will be critical to the integrity of the review process and the final determination of whether trainees are ready for unsupervised practice. Over time, these in-depth reviews will undoubtedly make CCCs privy to knowledge about the quality and quantity of assessments and the absence of curricular elements as they consider assessment evidence for each milestone. Thus, CCCs will become aware of gaps within their program's current assessment approach and the curriculum as a whole. Residency and fellowship programs will need to clarify the role of their CCC2 and specify what authority it will have in promoting needed change relative to assessment practices, faculty development,3 and curricular changes.

A Systems Approach

The CCC members may be helped by viewing assessment as a system,4 rather than as independent assessment events. Utilizing a systems thinking lens5–8 will prompt CCC members to examine the purpose and function of assessment processes, the amount and quality of evidence, and feedback loops within their programs. We believe a systems approach to assessment will result in useful and defendable performance appraisals.

Relationships with Stakeholders

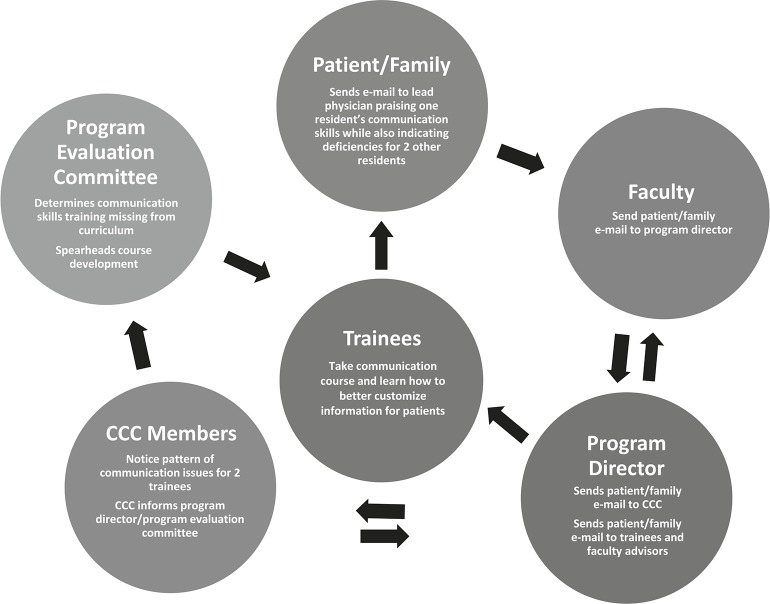

All systems include multiple stakeholders. A residency program's assessment system will include, but may not be limited to, the following stakeholders: residency program leaders, the CCC, chief residents, assessors (faculty and others), faculty development providers, trainees, the program evaluation committee, curriculum developers, and ultimately the public. For optimal program improvement, feedback loops6,9,10 between the CCC and other stakeholders may need to be examined and strengthened (figure). While department-wide faculty development is not part of the CCC's mission, feedback from the CCC to the program director may include recommendations for enhanced faculty development efforts for those engaged in assessment. For instance, if CCC members discover that faculty on the same rotation appear to be using different criteria to assess the same group of trainees (a reliability issue), feedback to the program director will be critical for enhancing the performance appraisal process.

FIGURE .

Example of a Feedback Loop

Abbreviation: CCC, Clinical Competency Committee.

Rethinking Assessment

Milestones Are Not Assessments

Milestones are developmental markers on the path to independent practice.11 Milestones offer specific performance criteria, which were lacking within prior ACGME competency language.11 The goal within competency frameworks is to provide continuous formative feedback to learners to promote optimal performance and support assessment for learning.12 The use of milestones can theoretically allow individual trainees to identify areas for improvement at an earlier stage. In the past, this was not always possible when using competencies and subcompetencies to guide assessment. In addition, curricular and assessment shortcomings within training programs as a whole may be identified, such as assessments that measure constructs or skills too broadly. Programs will need to identify assessment tools that answer specific questions. Yet, even the perfect tool will not guarantee valid scores if faculty differ in how they use these tools. Faculty development will be critical in ensuring that all assessors understand the what, how, and why of assessment. The milestone review process thus has the potential to promote change at the program level as well.

What You May Need Is Evidence—Not Another Assessment Tool

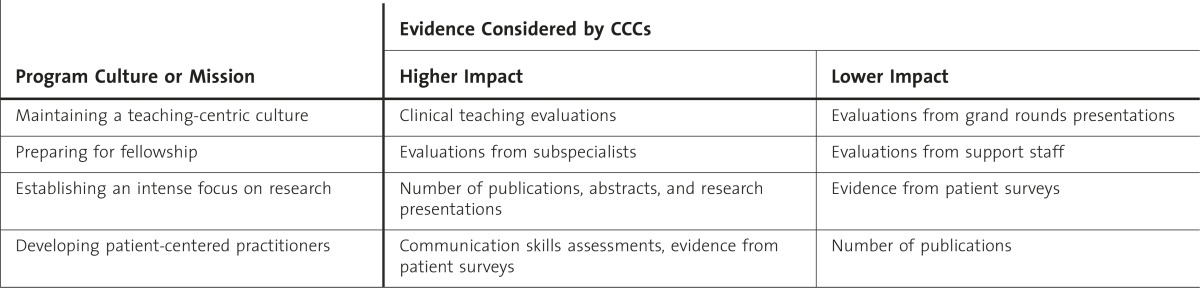

As residency and fellowship programs are confronted with ACGME mandates, they may rush to create new assessment tools to measure the milestones, give their faculty copies of the entire set of milestones to assess trainees, or add milestone language to the single evaluation form used at the end of each rotation. We argue that rather than focusing exclusively on assessment tools, CCCs will need to identify a wide range of evidence—from multiple sources and contexts—to ensure the validity of performance appraisals.13 Evidence can take many forms,14 including artifacts (eg, published articles/abstracts, awards for best oral presentation, case logs, and committee membership lists); data from assessment tools (eg, in-training examination scores, faculty assessments, 360-degree evaluations, and patient surveys); and even chart audits, quality improvement project notes, or simulation training activities. We recommend that CCCs use a template that includes specific criteria to allow for a standardized approach to the analysis and synthesis of evidence during trainee reviews. The criteria to be included in a CCC review template will be influenced by the values and mission of individual training programs (table).

TABLE .

Impact of Program Culture or Mission on How Evidence is Considered by the Clinical Competency Committee (CCC)

CCC members will be called on to synthesize and interpret information in order to make promotion recommendations. These judgments are not simply a summing up of multiple assessments. Rather, they require careful weighing of evidence against discrete outcomes. The discovery of discrepant data or information that contradicts other evidence will need to be examined and investigated. Dealing with this requires professional judgment.

Do You Need a Culture Change?

Promoting a Culture of Continuous Improvement

When engaging in the milestone review process, CCC members may be confronted with evidence that their program is overly reliant on summative (evaluative, infrequent) assessments. To successfully implement a culture that promotes learning and performance improvement, the meaning and value placed on assessment—especially high-stakes assessment—may need to undergo a dramatic change. More emphasis will need to be placed on formative assessment (informal, frequent) throughout training programs12,15 to ensure that assessment functions to support learning. Feedback, based on focused observations and specific criteria, is necessary to ensure continuous performance improvement.3,15,16 This may be a radical change for programs that emphasize summative assessments, including the ubiquitous end-of-rotation evaluations, rather than provide continuous feedback to learners.

A Shift to Learner Accountability

For programs that overwhelmingly use teacher-centered assessment, a culture shift to promote learner accountability will be necessary. Residents and fellows will need to know what they should be learning and should be expected to contribute to their own learning.12 They will need to understand the range of evidence (from assessment tool data to publications) that will be used to make judgments about their performance. They will also need to understand the role feedback can play in learning, performance improvement, and their own self-assessments.16,17 We recommend that trainees take an active role in the milestone assessment process. For some competency domains, a portfolio model, where trainees actively collect evidence and reflect on experiences,18–22 may be an attractive approach.

Conclusion

The milestone project is an opportunity for implementing a new assessment culture within graduate medical education programs, one that embraces authentic, work-based assessment and uses both assessment of learning (summative) and assessment for learning (formative) to support continuous performance improvement. Faculty may benefit from adopting a systems approach to assessment to promote open communication among all stakeholders. Programs that embrace this culture change will undoubtedly reap the benefits of promoting trainee progression through the milestones, as envisioned by the ACGME.

Footnotes

Colleen Y. Colbert, PhD, is Director, Faculty Development, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University and the Center for Educational Resources, Cleveland Clinic, and Member of the Internal Medicine Residency Program Clinical Competency Committee (CCC), Cleveland Clinic; Elaine F. Dannefer, PhD, is Director, Medical Education Research and Assessment, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University; and Judith C. French, PhD, is Surgical Educator, Department of General Surgery, and Chair, Surgery Residency Program CCC, Cleveland Clinic.

References

- 1.Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):648–654. doi: 10.1080/01421590701392903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French JC, Dannefer EF, Colbert CY. A systematic approach to building a fully operational clinical competency committee. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e22–e27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr KP, Massagli TL. New challenges for the graduate medical educator: implementing the milestones. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(7):624–631. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Vleuten CP, Dannefer EF. Towards a systems approach to assessment. Med Teach. 2012;34(3):185–186. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.652240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montuori LA. Organizational longevity—integrating systems thinking, learning, and conceptual complexity. J Org Change Manag. 2000;13(1):61–73. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colbert CY, Ogden PE, Ownby AR, Bowe C. Systems-based practice in graduate medical education: systems thinking as a foundational construct. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23(2):179–185. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2011.561758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werhane PH. Moral imagination and systems thinking. J Bus Ethics. 2002;38(1–2):33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch OJ, King CA, Herbohn JL, Russell IW, Smith CS. Getting the big picture in natural resource management—systems thinking as “method” for scientists, policy makers and other stakeholders. Syst Res Behav Sci. 2007;24(2):217–232. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong EG, Mackey M, Spear SJ. Medical education as a process management problem. Acad Med. 2004;79(8):721–728. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed GE. Leadership and systems thinking. Defense AT&L. 2006;35:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Slide presentations for faculty development: Clinical Competency Committee. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/442/GraduateMedicalEducation/SlidePresentationsforFacultyDevelopment.aspx. Accessed June 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dannefer EF. Beyond assessment of learning toward assessment for learning: educating tomorrow's physicians. Med Teach. 2013;35(7):560–563. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.787141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryman A. Triangulation. In: Lewis-Beck MS, Bryman A, Liao TF, editors. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2003. http://www.sagepub.com/chambliss4e/study/chapter/encyc_pdfs/4.2_Triangulation.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zubizaretta J. The learning portfolio: a powerful idea for significant learning. IDEA Paper No. 44. http://ideaedu.org/sites/default/files/IDEA_Paper_44.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadler DR. Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instruct Sci. 1989;18:119–144. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hattie J, Temperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2007;77(1):81–112. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shute VJ. Focus on formative feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2008;78(1):153–189. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colbert CY, Ownby AR, Butler PM. A review of portfolio use in residency programs and considerations before implementation. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(4):340–345. doi: 10.1080/10401330802384912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dannefer EF, Henson LC. The portfolio approach to competency-based assessment at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2007;82(5):493–502. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803ead30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Sullivan PS, Reckase MD, McClain T, Savidge MA, Clardy JA. Demonstration of portfolios to assess competency of residents. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2004;9(4):309–323. doi: 10.1007/s10459-004-0885-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Sullivan P, Greene C. Portfolios: possibilities for addressing emergency medicine resident competencies. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(11):1305–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fung MF, Walker M, Fung KF, Temple L, Lajoie F, Bellemare G, et al. An Internet-based learning portfolio in resident education: the KOALA multicentre programme. Med Educ. 2000;34(6):474–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]