Abstract

BACKGROUND

Individuals with schizophrenia have low employment rates and the job interview presents a critical barrier for them to obtain employment. Virtual reality training has demonstrated efficacy at improving interview skills and employment outcomes among multiple clinical populations. However, the effects of this training on individuals with schizophrenia are unknown. This study evaluated the efficacy of virtual reality job interview training (VR-JIT) at improving job interview skills and employment outcomes among individuals with schizophrenia in a small randomized controlled trial (n=21 VR-JIT trainees, n=11 waitlist controls).

METHODS

Trainees completed up to 10 hours of virtual interviews using VR-JIT, while controls received services as usual. Primary outcome measures included two pre-test and two post-test video-recorded role-play interviews scored by blinded human resource experts and self-reported interviewing self-confidence. Six-month follow-up data on employment outcomes were collected.

RESULTS

Trainees reported the intervention was easy-to-use, helpful, and prepared them for future interviews. Trainees demonstrated increased role-play scores between pre-test and post-test while controls did not (p=0.001). After accounting for neurocognition and months since prior employment, trainees had greater odds of receiving a job offer by 6 month follow-up compared to controls (OR: 8.73, p=0.04) and more training was associated with fewer weeks until receiving a job offer (r=−0.63, p<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Results suggest VR-JIT is acceptable to trainees and may be efficacious for improving job interview skills in individuals with schizophrenia. Moreover, trainees had greater odds of receiving a job offer by 6-month follow-up. Future studies could evaluate the effectiveness of VR-JIT within community-based services.

Keywords: schizophrenia, virtual reality training, job interview skills, vocational outcomes

1. Introduction

Less than 20% of individuals with schizophrenia attain employment (Rosenheck et al., 2006; Salkever et al., 2007), while this rate climbs to 30–40% for individuals in Individual Placement and Support (IPS) services (Drake and Bond, 2011). Successfully navigating the job interview is critical to attaining employment and is the most proximal step to attaining employment for IPS clients (Corbiere et al., 2011). Moreover, social cognitive and neurocognitive deficits that characterize schizophrenia have been associated with poorer vocational outcomes (Eack et al., 2011; Martinez-Dominguez et al., 2015; Vargas et al., 2014), and likely increase the difficulty of interviewing. Although individuals with schizophrenia self-identify having poor interview skills and want services to enhance these skills (Marwaha and Johnson, 2006; Solinski et al., 1992), there is a paucity of evidence-based interventions targeting interview skills (Bell and Weinstein, 2011).

Recently, two randomized controlled trials (RCT) evaluated virtual reality job interview training (VR-JIT), which demonstrated acceptability and efficacy at improving interview skills and self-confidence for individuals primarily diagnosed with mood disorders and veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Smith et al., in press-a; Smith et al., 2014b). Moreover, VR-JIT trainees sustained their self-confidence and were more likely to receive job offers than controls when evaluated six months later. Additionally, completing more VR-JIT trials was associated with greater odds of receiving a job offer and spending fewer weeks searching for employment (Smith et al., in press-b).

Thus, we hypothesized that 1) individuals with schizophrenia randomized to training would find VR-JIT acceptable and enhance their interviewing skills and interviewing self-confidence compared to waitlist controls; 2) trainees with schizophrenia would sustain their enhanced self-confidence and have greater odds of receiving a job offer compared to controls at 6-month follow-up; and 3) a greater number of completed VR-JIT trials, improved VR-JIT performance across trials, and self-confidence at the conclusion of training would be correlated with receiving a job offer and with fewer weeks until a job was offered. We generated these directional hypotheses based on our prior research (Smith et al., in press-b).

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants included 32 individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder recruited through Northwestern University’s Schizophrenia Research Group. Bachelor’s or Ph.D-level research staff determined diagnoses (and antipsychotic treatment) using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-TR (SCID-IV) (First et al., 2002). Inclusion criteria included: 18–55 years old, minimum of a 6th grade reading level using the Wide Range Achievement Test-IV (WRAT-IV) (Wilkinson and Robertson, 2006), willingness to be video-recorded, unemployed or underemployed, and actively seeking employment. Exclusion criteria included: having a medical illness that significantly comprised cognition (e.g., traumatic brain injury), uncorrected vision or hearing problem, or current substance abuse. Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and all participants provided informed consent.

Once enrolled, participants were randomized using a random number generator into training (n=17) or treatment-as-usual waitlist control (n=8) groups at an estimated ratio of 2 to 1 to optimize VR-JIT evaluation. Four trainees and three controls with schizophrenia completed prior RCTs of VR-JIT (Smith et al., in press-a; Smith et al., 2014b) and their data were included in all current analyses to optimize statistical power with final sample sizes of n=21 trainees and n=11 controls. Participants were re-contacted after 6 months and asked to complete a follow-up survey. Of the original 32 participants, 30 (94%) completed the follow-up survey and 2 (6%) were lost to contact.

2.2 Intervention

Virtual Reality Job Interview Training (VR-JIT) is a computer-based intervention developed by SIMmersion LLC (http://www.simmersion.com) to improve interviewing skills for adults with a range of disabilities. See Supplemental Material and Smith et al. (2014b) for details on VR-JIT design, use, and delivery (e.g., fidelity training).

2.3 Study Procedures

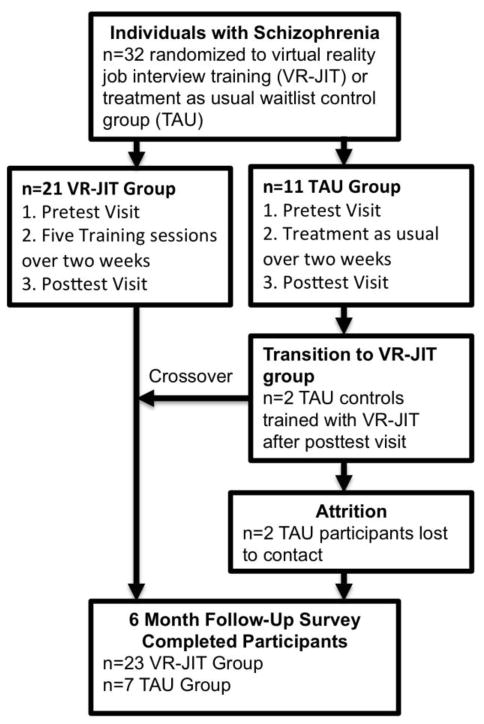

Pre-test measures included demographic, clinical, and vocational interviews; clinical, neurocognitive, and social cognitive assessments; and self-reported self-confidence and two standardized video-recorded role-plays. Participants were randomized following pre-test assessments. Trainees completed up to 10 hours of VR-JIT (approximately 20 trials) over the course of 5 visits (across 5–10 business days). Controls received services-as-usual for 5–10 business days. Both groups returned after ten business days to complete post-test measures of self-confidence and two standardized video-recorded role-plays, while trainees also completed the Treatment Experience Questionnaire (TEQ). After the post-test visit, all controls were invited from the waitlist to use VR-JIT. Two controls used VR-JIT and crossed-over to the training group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of study participation

Research staff contacted participants to complete a follow-up survey over the phone or via email approximately 6 months after completing the efficacy trial. Two controls were unreachable by phone, mail, and email, and were lost to contact. Overall, 23 VR-JIT and 7 controls completed follow-up (Figure 1).

2.4 Study Measures

2.4.1 Participant Characteristics

We assessed demographic characteristics and vocational history via self-report. Symptoms were assessed using global ratings from the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms and the Scale for the assessment of Negative Symptoms (Andreasen, 1983a, b). For the 7 participants who completed prior studies (Smith et al., in press-a; Smith et al., 2014b), we used ratings and notes from the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview to inform symptom ratings and SCID diagnosis.

2.4.2 Cognition

We assessed global cognitive ability with the total score from the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (Randolph et al., 1998). We assessed basic social cognition using the Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (Bell et al., 1997), and advanced social cognition using an emotional perspective-taking task (Smith et al., 2014c). Accuracy ratings for each task were generated using the number of correct responses.

2.4.3 VR-JIT Acceptability

We recorded trainee attendance across five sessions and the number of minutes (600 minutes possible) that they engaged in virtual interviews. Trainees completed the TEQ to evaluate whether they felt VR-JIT was easy to use, enjoyable, helpful, instilled confidence, and prepared them for interviews (Bell and Weinstein, 2011). The TEQ used a 7-point Likert scale with higher scores reflecting more positive views (α=0.86).

2.4.4 VR-JIT Efficacy

Role-Play Performance

Job interview role-plays (approximately 20 minutes each) were scored across nine domains: 1) conveying oneself as a hard worker, 2) sounding easy to work with, 3) conveying that one behaves professionally, 4) negotiation skills (requesting Thursdays off), 5) sharing things in a positive way, 6) sounding honest, 7) sounding interested in the position, 8) comfort level, and 9) establishing rapport adapted from prior work (Huffcutt, 2011). Role-play videos were randomly assigned to two blinded raters with more than 15 years of experience in human resources. Total scores for two baseline and two follow-up role-plays were computed across the nine domains (range of 1–5, higher scores reflecting better performance), and averaged to compute a single score.

Interviewing Self-Confidence

Participants rated their self-confidence at interviewing using a 7-point Likert scale to answer nine questions, with higher scores reflecting more positive views (e.g., “How comfortable are you going on a job interview?”). Total scores at pre-test and post-test had strong internal consistencies (α=0.95 and α=0.92, respectively).

VR-JIT Process Measures

We recorded trainees’ VR-JIT performance scores, number of completed trials, and time spent performing virtual interviews. Each virtual interview was scored 0–100 using an algorithm that assessed the appropriateness of responses based on eight domains: negotiation skills, conveying that you’re a hard worker, sounding easy to work with, sharing things in a positive way, sounding honest, sounding interested in the position, behaving professionally, and establishing interviewer rapport.

2.4.5 Six-Month Follow-up Measures

The follow-up survey asked participants to reflect on the past 6 months and report 1) total number of weeks they searched for employment, 2) number of job interviews completed, and 3) number of job offers received and accepted. The survey also reassessed interviewing self-confidence (α=0.89). The 6-month survey also assessed whether trainees felt VR-JIT prepared them for real interviews, helped them attain employment, and if revisiting VR-JIT would prepare them for future interviews. These items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree).

3. Data Analysis

3.1 Efficacy Study

Between-group differences for demographics, vocational history, cognition, and clinical history were assessed with a Mann-Whitney independent samples test or chi-square analysis. We used descriptive statistics to assess VR-JIT acceptability via session attendance, VR-JIT usage (in minutes), and mean responses to the TEQ. A repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA), using group as a fixed factor and assessment scores as repeated measures, evaluated whether primary outcomes (role-play performance and interviewing self-confidence) significantly improved between pre-test and post-test for trainees as compared to controls. Cohen’s d effect sizes characterized the within-participant differences.

We evaluated VR-JIT performance score improvement across trials as a process measure by computing linear regression slopes for each participant based on the regression of their performance scores on the log of trial number. The group-level performance average for each successive VR-JIT trial was plotted with a report of the R-Square from the regression of average performance on the log of trial number.

3.2 Six Month Follow-up

Among trainees, we conducted a pairwise t-test to evaluate whether post-test self-confidence was sustained at 6-month follow-up. We conducted a logistic regression with job offer (1=yes, 0=no) as the dependent variable to evaluate whether or not trainees had higher odds of receiving a job offer than controls. Neurocognition and number of months since prior employment were included as covariates given their relationship to vocational outcomes in this population (Burke-Miller et al., 2006; Catty et al., 2008). Odds ratios (OR) were generated with 95% Confidence Intervals. Nagelkerke R2 provided the model’s proportion of explained variance. We conducted point serial correlations to evaluate whether receiving a job offer was associated with VR-JIT process measures (i.e., total number of completed VR-JIT trials, the VR-JIT performance slope, total amount of time spent with VR-JIT) and self-confidence at 6-month follow-up. We conducted Pearson correlations to evaluate whether the number of weeks searching for employment was associated with VR-JIT process measures and self-confidence at 6-month follow-up.

4. Results

4.1 Pre-test Between-Group Characteristics

Trainees and controls did not differ with respect to demographics as well as clinical, cognitive, and vocational history (all p>0.10). Despite random assignment, anhedonia ratings differed between groups (but were missing for nine participants) (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Control Group (n=11) | VR-JIT Group (n=21) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean years (SD) | 39.1 (10.6) | 40.8 (12.2) | 0.76 |

| Gender (% male) | 54.5% | 52.4% | 0.34 |

| Parental education, mean years (SD) | 11.7 (1.8) | 12.9 (3.4) | 0.46 |

| Race | |||

| % Caucasian | 27.3% | 28.6% | |

| % African-American | 54.5% | 66.7% | 0.29 |

| % Latino | 18.2% | 4.8% | |

| Vocational history | |||

| Months since prior employment, mean (SD)a | 26.9 (41.0) | 65.2 (92.4) | 0.27 |

| Prior full-time employment (%) | 63.6% | 71.4% | 0.87 |

| Prior paid employment (any type) (%) | 100% | 95.2% | 0.53 |

| Prior participation in vocational training program | 27.3% | 38.1% | 0.37 |

| Cognitive function | |||

| Neurocognition, mean (SD) | 72.5 (12.6) | 74.8 (16.4) | 0.76 |

| Basic social cognition, mean (SD) | 0.71 (0.2) | 0.69 (0.1) | 0.67 |

| Advanced social cognition, mean (SD) | 0.77 (0.1) | 0.74 (0.1) | 0.88 |

| Clinical history | |||

| Duration of illness, mean years (SD) | 16.0 (11.4) | 19.5 (11.2) | 0.41 |

| Clinical symptoms | |||

| Hallucinations | 2.36 (2.1) | 1.71 (1.8) | 0.34 |

| Delusions | 2.36 (2.1) | 2.50 (1.9) | 0.88 |

| Bizarre behavior | 0.36 (0.8) | 0.95 (1.2) | 0.24 |

| Thought disorder | 1.18 (1.3) | 0.90 (1.3) | 0.56 |

| Affective flattening | 1.64 (1.4) | 1.86 (1.6) | 0.73 |

| Alogia | 1.27 (1.3) | 1.14 (1.5) | 0.79 |

| Avolitionb | 2.90 (0.8) | 2.90 (1.1) | 0.86 |

| Anhedoniac | 2.38 (1.6) | 3.73 (1.4) | 0.05 |

| Attentionc | 1.75 (0.9) | 2.00 (1.5) | 0.73 |

| Chlorpromazine equivalent | 245.25 (164.9) | 340.81 (197.9) | 0.18 |

| Treated with atypical antipsychotic medication | 81.8% | 90.0% | |

| Treated with typical antipsychotic medication | 18.2% | 10.0% | 0.52 |

two outliers excluded for VR-JIT trainees: 324 months and 276 months;

one VR-JIT trainee was not rated on this domain;

three controls and six VR-JIT trainees were not rated on this domain

4.2 VR-JIT Acceptability

VR-JIT sessions were well attended, trainees completed mean=15.7 (sd=4.3) trials, and participants reported that VR-JIT was easy to use, enjoyable, helpful, and increased their self-confidence in interviewing (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean Characteristics of VR-JIT Acceptability (SD)

| Attendance measures | |

| % Session attendance | 90.0% |

| Elapsed simulation time (min) | 537.9 (102.9) |

| TEQ Items | |

| Ease of use | 6.0 (1.0) |

| Enjoyable | 6.7 (0.7) |

| Helpful | 6.6 (0.7) |

| Instilled confidence | 5.9 (1.2) |

| Prepared for interviews | 6.0 (1.0) |

Note. Scale for TEQ, 1=Extremely Unhelpful to 7=Extremely Helpful

4.3 VR-JIT Process Measures

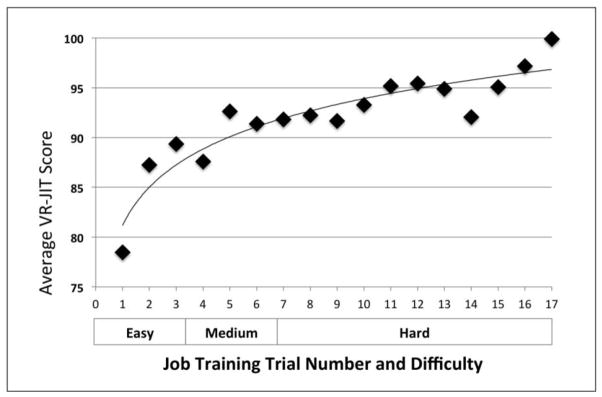

VR-JIT performance scores improved linearly across the number of completed trials (Figure 2). The slope (mean=4.8, sd=3.7) suggests that performance improved 4.8 points for every 1 point increase in the natural log of trial number (R-Squared= 0.86).

Figure 2.

VR-JIT learning curve in individuals with schizophrenia. This figure plots the average score for each successive VR-JIT virtual interview trial. Trials 1–3 at easy, trials 4–6 at medium, and trials 7–17 at hard. Model fit, R2=0.85.

4.4 Primary Outcomes for Efficacy Study

RM-ANOVA revealed a significant group-by-time interaction for role-play performance (F1,30=13.9, p=0.001). Trainees improved their role-play performance between pre-test and post-test, which was characterized by a large effect size (d=0.92). Controls appeared to regress to the mean (d=−0.42) (Table 3). RM-ANOVA revealed a non-significant group-by-time interaction for self-confidence scores (F1,30=1.6, p=0.11), but trainees were characterized by a medium effect size (d=0.59) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Unadjusted means for efficacy study primary outcome measures

| Control Group | VR-JIT Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Pretest mean (SD) | Posttest mean (SD) | Cohen’s d | Pretest mean (SD) | Posttest mean (SD) | Cohen’s d | |

| Role-play performancea | 34.9 (3.6) | 33.6 (3.3) | −0.42 | 33.8 (5.9) | 36.5 (4.4) | 0.92 |

| Interviewing self-confidencea | 41.9 (14.0) | 44.2 (11.5) | 0.30 | 42.5 (13.7) | 50.2 (8.8) | 0.58 |

One training group participant scored 3 standard deviations below the mean on the pretest and post test means and was removed from this particular analysis.

4.5 6-Month Vocational Outcomes

Trainees sustained interviewing self-confidence between the post-test (m=50.2, sd=8.8) and 6-month follow-up (m=49.0, sd=9.5) (T20=0.92, p>0.10, d=−0.13). This analysis excluded the two controls who crossed-over to the VR-JIT group. More trainees received job offers (47.8%) than controls (14.3%), which was a trend-level difference (p=0.055). The groups did not differ with respect to the proportion of participants who completed interviews, accepted job offers, total number of interviews completed, or number of weeks they searched for employment (all p>0.10) (Table 4).

Table 4.

6-Month follow-up between-group differences

| N | Control Group (n=7) | N | VR-JIT Group (n=23) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean total weeks looking for a job (SD) | 17.3 (8.5) | 11.3 (10.0) | 0.11 | ||

| Mean total job interviews completed (SD) | 1.3 (0.8) | 2.3 (2.3) | 0.31 | ||

| % of subjects who completed job interviews | 6 | 85.7% | 19 | 82.6% | 0.85 |

| % of subjects who received job offer | 1 | 14.3% | 11 | 47.8% | 0.055 |

| % of subjects who accepted job offer | 1 | 100.0% | 9 | 81.8% | 0.22 |

The logistic regression revealed the odds of attaining a job offer were 8.73 times higher for trainees compared to controls (OR=8.73, p=0.04; 95% CI=1.17, 65.00) after accounting for neurocognition and months since prior employment (non-significant predictors). Overall, the model explained 20.3% of the variance in job offers (Table 5).

Table 5.

VR-JIT as a predictor of receiving a job offer

| Step 1 OR (C.I. 95%) |

Step 2 OR (C.I. 95%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Step 1a | ||

| Neurocognition | 0.97(0.92–1.01) | 0.97(0.92–1.01) |

| Months since prior employment | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) |

| Step 2b | ||

| VR-JIT (yes or no) | -- | 8.73 (1.17–65.00)* |

|

| ||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.033 | 0.203* |

Step 1 Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients, Chi-Square=0.73, df=2, p=0.69

Step 2 Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients, Chi-Square=4.15, df=1, p=0.02

p<0.05

Among trainees, completing more VR-JIT trials correlated with fewer weeks searching for employment (r=−0.63, p<0.001) and greater improvement in self-confidence (r=0.46, p=0.03). A larger VR-JIT performance slope correlated with greater improvement in role-play performance (r=0.46, p=0.03). Remaining correlations were non significant (Supplemental Table 1).

More than 80% of trainees strongly agreed or agreed that VR-JIT prepared them for real interviews and they would use VR-JIT again to enhance their skills. Fifty-six percent of trainees agreed or strongly agreed that VR-JIT helped them get a job.

5. Discussion

We examined the acceptability and efficacy of VR-JIT in employment-seeking individuals with schizophrenia. Trainees reporting VR-JIT was easy to use, enjoyable, helpful, and improved their confidence for future interviews. Also, trainees improved their virtual interview scores across increasing levels of difficulty and their role-play performance scores. At 6-month follow-up, trainees had greater odds of receiving a job offer. Moreover, the regression was conducted while covarying for known predictors of employment (Burke-Miller et al., 2006; Catty et al., 2008). Also, more training was associated with fewer weeks searching for employment and trainees felt VR-JIT prepared them for interviews they encountered in real-life.

The observed improvement in interviewing skills in this cohort is consistent with the evaluation of VR-JIT in other clinical populations (Smith et al., in press-a; Smith et al., 2014a; Smith et al., 2014b). Also, our findings that trainees with schizophrenia had greater odds of receiving job offers and higher doses of training were related to fewer weeks of job searching replicated the results from a recent 6-month follow-up study of a cohort primarily diagnosed with mood disorders or PTSD (Smith et al., in press-b).

There are several directions for future research. First, one could evaluate whether VR-JIT improves vocational outcomes in larger samples enrolled in evidence-based vocational services such as IPS, which has better vocational outcomes than conventional practice (Drake and Bond, 2011). Since the vast majority of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders do not have access to IPS, VR-JIT could be evaluated independently or as a complement to available vocational services. Due to the web-based interface, VR-JIT can be widely disseminated to treatment centers with little access to vocational services.

Several limitations must be considered. There was limited statistical power due to a small sample. Data on the types of jobs attained or pay received were not collected, and 6-month data was self-reported. The findings only generalize to individuals actively seeking jobs. Also, two controls crossed-over to the training group, which enhances our understanding of VR-JIT but could limit the generalizability of controls. We did not assess Parkinsonian symptoms or anticholinergic treatment, which could impact interviewing performance. All participants were paid for their study efforts (including the intervention phase), which may create bias. Thus, future research needs to evaluate outcomes by unpaid trainees. Both groups had similar demographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics, and job-seeking behaviors (i.e., proportion of completed interviews, length of job search), which are notable strengths of the sample.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, VR-JIT is a promising intervention given that trainees improve their interviewing skills and have greater odds of receiving a job offer. Moreover, the amount of training was associated with receiving a job offer more quickly. Future studies should evaluate whether VR-JIT can enhance vocational outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia with and without access to evidence-based vocational services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This study was primarily funded by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Additional funding for the study was provided by an NIMH grant awarded to Dr. Dale Olsen (R44 MH080496).

Support for this work was provided by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Zoran Martinovich for advising on statistical issues, the research staff at Northwestern University’s Schizophrenia Research Group and Clinical Research Program for data collection, and our participants for volunteering their time.

Footnotes

Dr. Olsen and Ms. Humm contributed to the design of the study and manuscript preparation, but were not involved in the collection or analysis of data.

Contributors

All authors have made significant scientific contributions to this manuscript. Matthew J. Smith contributed to the conceptualization of the study, conducted the statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Drs. Fleming, Olsen, and Bell contributed to the conceptualization of the study and assisted with manuscript editing. Mr. Wright and Ms. Boteler Humm assisted with study conceptualization and manuscript editing. Ms. Roberts assisted with writing the introduction and overall manuscript editing. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Olsen and Laura Boteler-Humm are employed by and own shares in SIMmersion LLC. They contributed to the manuscript, but were not involved in analyzing the data. Dr. Bell was a paid consultant by SIMmersion LLC to assist with the development of VR-JIT. Dr. Bell and his family do not have a financial stake in the company. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. The University of Iowa; Iowa City, IA: 1983a. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms. The University of Iowa; Iowa City, IA: 1983b. [Google Scholar]

- Bell M, Bryson G, Lysaker P. Positive and negative affect recognition in schizophrenia: a comparison with substance abuse and normal control subjects. Psychiatry research. 1997;73(1–2):73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Weinstein A. Simulated job interview skill training for people with psychiatric disability: feasibility and tolerability of virtual reality training. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2011;37(Suppl 2):S91–97. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke-Miller JK, Cook JA, Grey DD, Razzano LA, Blyler CR, Leff HS, Gold PB, Goldberg RW, Mueser KT, Cook WL, Hoppe SK, Stewart M, Blankertz L, Dudek K, Taylor AL, Carey MA. Demographic characteristics and employment among people with severe mental illness in a multisite study. Community mental health journal. 2006;42(2):143–159. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-9017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catty J, Lissouba P, White S, Becker T, Drake RE, Fioritti A, Knapp M, Lauber C, Rossler W, Tomov T, van Busschbach J, Wiersma D, Burns T. Predictors of employment for people with severe mental illness: results of an international six-centre randomised controlled trial. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2008;192(3):224–231. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.041475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbiere M, Zaniboni S, Lecomte T, Bond G, Gilles PY, Lesage A, Goldner E. Job acquisition for people with severe mental illness enrolled in supported employment programs: a theoretically grounded empirical study. Journal of occupational rehabilitation. 2011;21(3):342–354. doi: 10.1007/s10926-011-9315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Bond GR. IPS Supported Employment: A 20 year Update. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2011;14(3):155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS. Effects of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy on Employment Outcomes in Early Schizophrenia: Results From a Two-Year Randomized Trial. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011;21(1):32–42. doi: 10.1177/1049731509355812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Miriam G, Williams JBW. Biometrics Research. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 2002. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Huffcutt AI. An empirical review of the employment interview construct literature. International Journal of Selection and Assessment. 2011;19(1):62–81. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Dominguez S, Penades R, Segura B, Gonzalez-Rodriguez A, Catalan R. Influence of social cognition on daily functioning in schizophrenia: study of incremental validity and mediational effects. Psychiatry research. 2015;225(3):374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwaha S, Johnson S. View and experiences of employment among people with psychosis: a qualitative descriptive study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2006;51(4):302–316. doi: 10.1177/0020764005057386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers WR. Handling missing data in clinical trials: an overview. Drug Information Journal. 2000;34:525–533. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 1998;20(3):310–319. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R, McEvoy J, Swartz M, Perkins D, Stroup S, Hsiao JK, Lieberman J. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163(3):411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkever DS, Karakus MC, Slade EP, Harding CM, Hough RL, Rosenheck RA, Swartz MS, Barrio C, Yamada AM. Measures and predictors of community-based employment and earnings of persons with schizophrenia in a multisite study. Psychiatric services. 2007;58(3):315–324. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Boteler Humm L, Fleming MF, Jordan N, Wright MA, Ginger EJ, Wright K, Olsen D, Bell MD. Virtual Reality Job Interview Training For Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. doi: 10.3233/JVR-150748. in press-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Fleming MF, Wright MA, Jordan N, Boteler Humm L, Olsen D, Bell MD. Job offers among individuals with severe mental illness after virtual reality job interview training. Psychiatric services. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400504. in press-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Ginger EJ, Wright K, Wright MA, Taylor JL, Humm LB, Olsen DE, Bell MD, Fleming MF. Virtual reality job interview training in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014a;44(10):2450–2463. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2113-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Ginger EJ, Wright M, Wright K, Boteler Humm L, Olsen D, Bell MD, Fleming MF. Virtual reality job interview training for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2014b;202(9):659–667. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Horan WP, Cobia DJ, Karpouzian TM, Fox JM, Reilly JL, Breiter HC. Performance-based empathy mediates the influence of working memory on social competence in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2014c;40(4):824–834. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinski S, Jackson HJ, Bell RC. Prediction of employability in schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 1992;7(2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas G, Strassnig M, Sabbag S, Gould F, Durand D, Stone L, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. The course of vocational functioning in patients with schizophrenia: Re-examining social drift. Schizophrenia research. Cognition. 2014;1(1):e41–e46. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test 4 Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, FL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.