Abstract

Purpose

Although breast conservation is therapeutically equivalent to mastectomy for most early-stage breast cancer patients, an increasing number are pursuing mastectomy, which may be followed by breast reconstruction. We sought to evaluate long-term quality of life (QOL) and cosmetic outcomes after different locoregional management approaches, as perceived by patients themselves.

Methods

We surveyed women diagnosed with non-metastatic breast cancer from 2005-07, as reported to the Los Angeles and Detroit population-based SEER registries. We received responses from 2290 women approximately 9 months after diagnosis (73% response rate) and from 1536 of these 4 years later. We evaluated QOL and patterns and correlates of satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes overall, and more specifically within the subgroup undergoing mastectomy with reconstruction, using multivariable linear regression.

Results

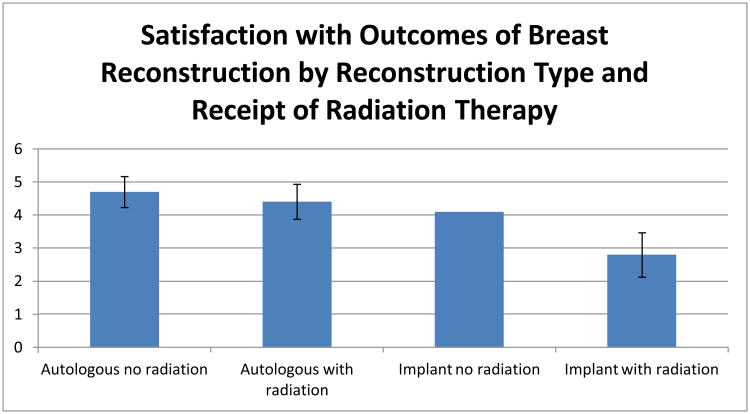

Of the 1450 patients who responded to both surveys and had not recurred, 963 underwent breast conserving surgery, 263 mastectomy without reconstruction, and 222 mastectomy with reconstruction. Cosmetic satisfaction was similar between those receiving breast conservation and those receiving mastectomy with reconstruction. Among patients receiving mastectomy with reconstruction, reconstruction type and radiation receipt were associated with satisfaction (p<0.001), with an adjusted scaled satisfaction score of 4.7 for patients receiving autologous reconstruction without radiation, 4.4 for patients receiving autologous reconstruction and radiation therapy, 4.1 for patients receiving implant reconstruction without radiation, and 2.8 for patients receiving implant reconstruction and radiation.

Discussion

Patient-reported cosmetic satisfaction was similar after breast conservation and after mastectomy with reconstruction. In patients undergoing post-mastectomy radiation, use of autologous reconstruction may mitigate radiation's deleterious impact on cosmetic outcomes.

Introduction

Randomized trials have established breast conservation as an equivalent alternative to mastectomy for most early-stage breast cancer patients.1 Nevertheless, a substantial minority of patients continue to receive mastectomy, a decision driven in some cases by patient preference and in others by contraindications to breast conservation.2 Some studies indicate that in the United States, rates of both unilateral3,4 and bilateral5 mastectomy are rising. The reason for the increased use of mastectomy is uncertain, although it appears to be driven by patient choice,2 and some have suggested that improved cosmetic outcome with modern techniques of breast reconstruction may contribute to this trend.6 The long-term quality of life (QOL) and cosmetic outcomes after different approaches can thus be an important consideration for patients when selecting a local therapy option for breast cancer treatment.

The patient's perception of cosmetic outcome is a critical endpoint,7 and measures of self-reported cosmetic outcome are now increasingly incorporated into breast cancer clinical trial design.8,9 Although interest in patient-reported outcomes has grown in recent years,10,11 to date, the literature has lacked information on patient-reported satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes of breast cancer treatment after the early post-operative period, particularly among breast cancer survivors who received their care in a variety of settings and with a variety of therapeutic approaches.

Therefore, in a sample of breast cancer survivors identified through two metropolitan population-based cancer registries, we sought to describe QOL and long-term patient-reported satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes after breast cancer treatment. Specifically, we compared outcomes among those receiving breast reconstruction after mastectomy to those undergoing mastectomy alone and those receiving breast conserving therapy. We further considered, in the subset receiving reconstruction, whether reconstruction type, timing, or patient characteristics were associated with cosmetic satisfaction. Because of the potential implications for clinical practice, we were particularly interested in evaluating the hypothesis that the influence of reconstruction type or timing on patient outcomes might differ in those patients who receive post-mastectomy radiotherapy, as compared to those who do not.

Methods

Sample

We conducted a longitudinal, multicenter cohort study of women diagnosed with breast cancer in metropolitan Los Angeles and Detroit. Patients aged 20-79 years and diagnosed with stage 0-III breast cancer between June 2005 and February 2007, as reported to the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) population-based program registries in those regions, were eligible for sample selection.

Patients were excluded if they had stage IV disease or could not complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish. Asian women in Los Angeles were excluded because of enrollment in other studies, and SEER protocol precludes patients from participating in more than one external study. Latina and black patients were oversampled to ensure sufficient minority representation.

Questionnaire Design and Content

We developed original questionnaires after considering existing literature, measures previously developed to assess relevant constructs, and theoretical models.12-15 We utilized standard techniques of content validation, including systematic review by design experts and cognitive pretesting with patients.

Data Collection

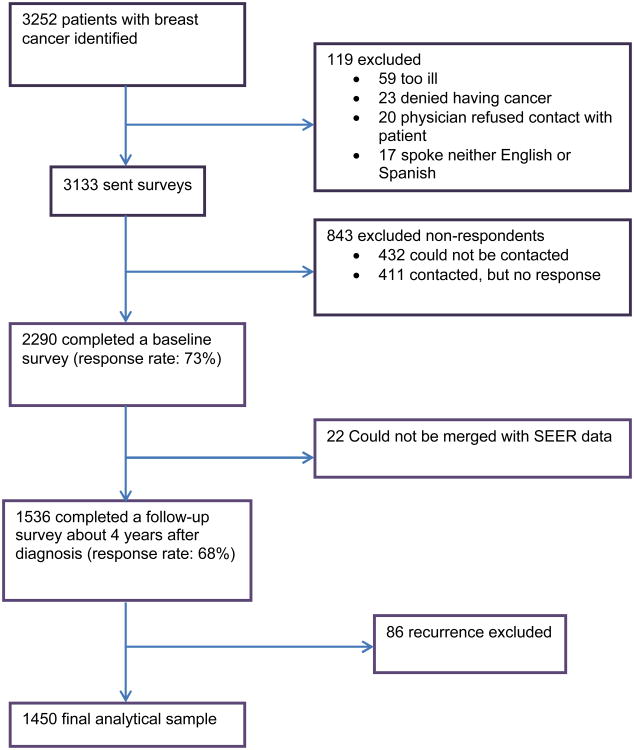

After IRB approval, eligible patients were identified via rapid case ascertainment. After notifying physicians, we first surveyed 3133 patients a mean of nine months after diagnosis (mean time from diagnosis to baseline survey return 288 days, SD 100). We then contacted all respondents approximately four years later to complete a follow-up survey (mean time from diagnosis to survey response 1524 days, SD 143). To encourage response, we provided a $10 cash incentive at each survey point and used a modified Dillman16 method, including reminders to non-respondents, achieving 73% and 68% response rates. All materials were sent in English and Spanish to those with Spanish surnames.17 Responses to the baseline and follow-up surveys were combined into a single dataset, into which clinical data from SEER was merged. The evolution of the sample is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient Flow into the Study. This figure depicts the flow of patients into the study from those initially identified to the final analytic sample.

Measures

We measured QOL using the validated FACT instrument, administered in the baseline and again in the follow-up survey. Our other key dependent variables were two measures of patient-reported satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes, one asked of all patients, and one specific to patients who received breast reconstruction (both derived from existing measures12-15); both were ascertained in the follow-up survey only, in order to avoid assessing cosmetic outcomes soon after surgery. As more fully described in the online-only supplementary appendix, the first measure (Satisfaction with Breast Cosmetic Outcomes) was a scale derived from a battery of questions posed to all patients, regardless of surgery type, that began by asking, “In the past 7 days, how satisfied have you been with…” and included items for “how you look in the mirror clothed, the shape of your breast(s) when you are wearing a bra, the shape of your breast(s) when you are not wearing a bra, how normal you feel in your clothes, how comfortably your bras fit, and how you look in the mirror unclothed.” The mean of the scale was 3.33 (SD 1.02), with a minimum of 1 and maximum of 5. Cronbach's alpha was 0.90, indicating high internal consistency in this scale.

The second measure of satisfaction (Satisfaction with Reconstruction Outcomes) was asked only of patients who reported that they had undergone breast reconstruction. Patients were asked to rate, from very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (5), their satisfaction with the overall results of reconstruction, reconstructed breast size, how natural the reconstructed breast(s) look, how the reconstructed breast(s) feel to touch, and how closely matched their breasts are to each other. The average of these five items was used to construct the scale. The scale ranged from 1 to 5, with a mean of 3.64 (SD 1.27). Cronbach's alpha was 0.91, indicating high internal consistency.

We considered several independent variables based upon our conceptual models. For analysis of the entire cohort, the key independent variable of interest was surgery type (breast conservation, mastectomy without reconstruction, or mastectomy with reconstruction). For analysis of the reconstructed subset, the key independent variables were reconstruction type (autologous tissue versus implant-based) and timing (immediate--at the same time as mastectomy--versus delayed). We also evaluated a number of other independent variables for inclusion in the models, based on our conceptual framework of the factors believed to be relevant. This included clinical factors: SEER-reported tumor size (grouped in 10mm increments) and nodal stage and self-reported adjuvant treatments (radiation and chemotherapy), laterality of the mastectomy (unilateral versus bilateral), comorbidities (grouped as 0, 1, 2 or more of the following proxies for vascular risk: stroke, MI, diabetes, or COPD), smoking, body-mass index (BMI), and bra cup size at time of diagnosis. This also included several sociodemographic factors determined in the baseline questionnaire: age (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Latina, or other), educational status (high school or less, some college, or college graduate), family income at diagnosis (<$20K, $20-$70K, >70K, and unknown), insurance (none, Medicare, Medicaid, and other/private), and marital status (married or partnered versus not). Finally, we considered geographic site (Los Angeles vs Detroit) as an independent variable in the analyses.

Statistical Analyses

After initial descriptive analyses, we conducted a longitudinal evaluation of QOL by surgery type, and we used two separate multivariable linear regressions to model cross-sectional long-term satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes, one for all patients and one for patients who underwent reconstruction alone. To achieve parsimony of the regression models, we used a backward variable selection method to eliminate the variables that did not reach the statistical significance level of 0.10. However, we retained certain variables of particular interest in the models regardless of the statistical significance; these variables included the key independent variables being investigated in the models (surgery type in the first model, reconstruction type and timing in the second) as well as control variables for age and the level of education for both models. Additionally, driven by our hypotheses, we explored potential interactions between reconstruction type and radiation receipt, as well as between reconstruction timing and radiation receipt. Where evidence of meaningful interactions was observed, we investigated the difference among the four fully interacted subgroups in the regression model.

As detailed in the online-only supplementary appendix, all statistical analyses incorporate weights to account for differential probabilities of sample selection and non-response.18 Weighting allows statistical inferences to be more representative of the target population. The jackknife resampling method was used to obtain estimates that are robust towards non-normal distributions. All analyses used SAS software, Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R package version 2.13 (Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 1536 patients completed both questionnaires; 86 were excluded due to tumor recurrence, leaving 1450 patients for the analysis of satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the analyzed sample, along with treatments received. Median age was 58. A substantial proportion of the sample was Black (17.3%) or Latina (39.5%). Educational attainment was high school or less for 42.2% of the sample, and 54.1% had Stage 0 or I disease. The majority of patients (n=963, 63%) underwent BCT, with the remainder fairly evenly divided between mastectomy alone (n=263) and mastectomy with reconstruction (n=222).

Table 1. Characteristics of Analyzed Sample (n=1450).

| Total | Mastectomy Without Reconstruction | Mastectomy With Reconstruction | Breast Conserving Therapy | p-value*** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N* | Wt%** | N | Wt%** | N | Wt%** | N | Wt%** | |

| Patient Characteristics | |||||||||

| Age at Diagnosis | <0.001 | ||||||||

| <46 | 217 | 16.8 | 27 | 11.8 | 72 | 34.9 | 118 | 14.1 | |

| 46-55 | 411 | 27.3 | 50 | 19.7 | 90 | 38.5 | 271 | 27.2 | |

| 56+ | 816 | 55.7 | 186 | 68.5 | 60 | 26.6 | 568 | 58.4 | |

| Missing | 6 | 0.2 | 0 | . | 0 | . | 6 | 0.3 | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||||||

| White | 714 | 43.3 | 111 | 36.7 | 122 | 46.9 | 481 | 44.8 | |

| Black | 362 | 17.3 | 66 | 18.1 | 38 | 11.5 | 256 | 18.1 | |

| Latina, English Speaking | 178 | 19.0 | 28 | 15.4 | 42 | 28.4 | 108 | 17.9 | |

| Latina, Spanish Speaking | 196 | 20.5 | 58 | 29.8 | 20 | 13.2 | 118 | 19.2 | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||||||||

| High school or less | 536 | 42.2 | 129 | 55.3 | 45 | 22.7 | 361 | 42.5 | |

| Some college | 487 | 31.0 | 67 | 20.7 | 89 | 42.6 | 331 | 31.8 | |

| College graduate or greater | 403 | 24.7 | 63 | 22.2 | 87 | 34.5 | 253 | 23.3 | |

| Missing | 24 | 2.1 | 4 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.2 | 18 | 2.4 | |

| Family Income at Baseline Survey | <0.001 | ||||||||

| <$20,000 | 246 | 18.6 | 67 | 24.9 | 17 | 7.4 | 162 | 19.2 | |

| $20,000-$69,999 | 534 | 35.4 | 88 | 32.1 | 79 | 37.8 | 366 | 36.1 | |

| $70,000+ | 407 | 25.5 | 47 | 16.1 | 99 | 41.8 | 261 | 24.9 | |

| Missing | 263 | 20.5 | 61 | 26.9 | 27 | 13.1 | 174 | 19.9 | |

| Insurance | <0.001 | ||||||||

| None | 85 | 7.9 | 26 | 12.0 | 13 | 6.2 | 46 | 6.9 | |

| Medicaid | 127 | 10.9 | 35 | 15.6 | 12 | 6.2 | 80 | 10.4 | |

| Medicare | 343 | 22.5 | 84 | 30.1 | 15 | 4.3 | 242 | 24.1 | |

| Other | 840 | 54.4 | 105 | 36.7 | 178 | 81.8 | 557 | 54.0 | |

| Missing | 55 | 4.3 | 13 | 5.7 | 4 | 1.5 | 38 | 4.6 | |

| Marital Status | 0.057 | ||||||||

| Not married or partnered | 611 | 41.7 | 123 | 44.9 | 72 | 33.3 | 415 | 42.5 | |

| Married or partnered | 828 | 57.4 | 138 | 54.4 | 150 | 66.7 | 539 | 56.3 | |

| Missing | 11 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | . | 9 | 1.2 | |

| Comorbidity | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 1157 | 80.1 | 185 | 72.1 | 202 | 92.0 | 768 | 80.0 | |

| 1 | 227 | 15.5 | 58 | 19.5 | 15 | 5.6 | 154 | 16.6 | |

| 2 or more | 66 | 4.4 | 20 | 8.5 | 5 | 2.4 | 41 | 3.4 | |

| Smoking history | 0.582 | ||||||||

| No | 1229 | 86.5 | 222 | 85.7 | 187 | 85.4 | 818 | 87.0 | |

| Yes | 207 | 12.3 | 38 | 12.7 | 35 | 14.6 | 134 | 11.6 | |

| Missing | 14 | 1.2 | 3 | 1.5 | 0 | . | 11 | 1.4 | |

| BMI | <0.001 | ||||||||

| <25 | 408 | 29.7 | 71 | 27.5 | 89 | 44.8 | 248 | 26.8 | |

| 25-31 | 514 | 35.3 | 76 | 30.8 | 72 | 30.9 | 365 | 38.0 | |

| >31 | 442 | 29.4 | 101 | 36.7 | 50 | 19.8 | 291 | 29.3 | |

| Missing | 86 | 5.6 | 15 | 5.1 | 11 | 4.5 | 59 | 5.8 | |

| Pre-diagnosis bra cup size | 0.312 | ||||||||

| A or B | 436 | 30.2 | 89 | 31.7 | 79 | 37.2 | 268 | 28.1 | |

| C | 509 | 36.0 | 94 | 37.4 | 71 | 34.3 | 344 | 36.1 | |

| D or greater | 415 | 27.6 | 67 | 25.4 | 64 | 24.9 | 284 | 29.2 | |

| Missing | 90 | 6.1 | 13 | 5.5 | 8 | 3.6 | 67 | 6.7 | |

| Geographic Site | 0.168 | ||||||||

| Los Angeles | 794 | 79.0 | 160 | 82.4 | 115 | 78.2 | 518 | 78.1 | |

| Detroit | 656 | 21.0 | 103 | 17.6 | 107 | 21.8 | 445 | 21.9 | |

| Tumor and Treatment Characteristics | |||||||||

| Stage | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 366 | 18.6 | 37 | 9.5 | 62 | 20.5 | 267 | 21.3 | |

| I | 537 | 35.5 | 75 | 25.3 | 58 | 23.3 | 403 | 42.2 | |

| II | 411 | 33.9 | 92 | 38.8 | 72 | 39.9 | 247 | 30.8 | |

| III | 128 | 11.3 | 57 | 24.8 | 30 | 16.3 | 40 | 5.1 | |

| Missing | 8 | 0.7 | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | . | 6 | 0.6 | |

| Bilateral mastectomy | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 1302 | 89.2 | 225 | 85.3 | 153 | 68.8 | 924 | 95.8 | |

| Yes | 110 | 8.1 | 25 | 10.4 | 67 | 30.7 | 18*** * | 1.7 | |

| Missing | 38 | 2.8 | 13 | 4.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 21 | 2.5 | |

| Radiation Receipt | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1007 | 67.6 | 84 | 35.6 | 60 | 27.5 | 863 | 88.8 | |

| No | 387 | 29.7 | 162 | 60.7 | 160 | 71.8 | 64 | 8.4 | |

| Missing | 56 | 2.7 | 17 | 3.7 | 2 | 0.6 | 36 | 2.8 | |

| Chemotherapy Receipt | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 659 | 52.1 | 158 | 63.9 | 120 | 65.0 | 380 | 44.8 | |

| No | 737 | 45.6 | 98 | 34.9 | 100 | 34.3 | 539 | 52.3 | |

| Missing | 54 | 2.2 | 7 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.7 | 44 | 2.9 | |

N and weighted % values do not add up to 1450 (100%) due to missing values

Weighted % values weighted by disproportionate survey sampling and non-response

P-value represents significance of differences in covariate by surgery subgroup.

A small number of patients who initially had breast conserving therapy went on to have bilateral mastectomy by the time of the four-year survey; 12 of these did so to prevent future breast cancer and 6 did so for contralateral cancer diagnosis.

Table 2 describes the QOL in our sample. We observed no significant differences in well-being by surgery type, except that there appeared to be a greater improvement in physical well-being by the time of the follow-up survey for patients who received mastectomy with breast reconstruction.

Table 2. Quality of Life as Measured by FACT*.

| Mastectomy, No Recon | Mastectomy with Recon | Breast Conservation | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||

| Physical Well-Being | |||||||

| T1 | 24.13 | 0.74 | 23.67 | 0.83 | 23.68 | 0.54 | 0.09 |

| T2 | 25.82 | 0.61 | 26.94 | 0.60 | 26.06 | 0.44 | 0.34 |

| Change | 3.91 | 0.51 | 5.22 | 0.50 | 4.17 | 0.37 | 0.02 |

| Social Well-Being | |||||||

| T1 | 22.04 | 0.56 | 22.79 | 0.62 | 21.98 | 0.42 | 0.30 |

| T2 | 19.56 | 0.50 | 20.50 | 0.54 | 20.00 | 0.38 | 0.24 |

| Change | -2.21 | 0.41 | -1.69 | 0.47 | -1.81 | 0.30 | 0.49 |

| Emotional Well-Being | |||||||

| T1 | 18.78 | 0.73 | 18.73 | 0.70 | 19.61 | 0.42 | 0.13 |

| T2 | 20.62 | 0.46 | 20.81 | 0.51 | 20.86 | 0.37 | 0.83 |

| Change | 1.47 | 0.40 | 1.68 | 0.45 | 1.65 | 0.33 | 0.85 |

| Functional Well-Being | |||||||

| T1 | 21.76 | 0.79 | 21.05 | 0.78 | 22.60 | 0.79 | 0.10 |

| T2 | 21.31 | 0.69 | 22.13 | 0.69 | 21.66 | 0.48 | 0.51 |

| Change | 2.02 | 0.60 | 2.65 | 0.65 | 1.86 | 0.46 | 0.31 |

All means are adjusted means based on models that control for potentially significant confounders. Means are calculated at mean levels of BMI, age, in non-Hispanic White patients who receive radiation but not chemotherapy, who lack major cardiovascular comorbidities, are non-smokers, have high-school or lower level of education, other/private insurance, tumor size >10 and ≤20mm, and negative lymph nodes.

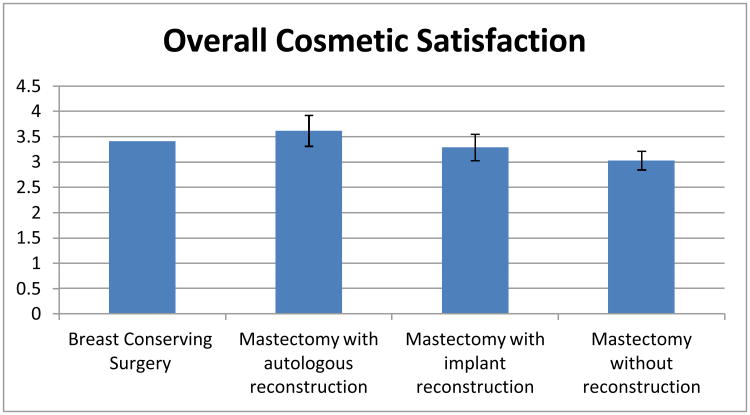

Table 3 presents a multivariable linear regression model of the scaled measure of Satisfaction with Breast Cosmetic Outcomes in the 1245 patients with complete variable information. Satisfaction was not significantly different between the group receiving breast conservation and the group receiving mastectomy with reconstruction with either implant technique or with autologous technique. Satisfaction was slightly but significantly lower (0.38) worse on a 5-point scale, 95% CI: {-0.56, -0.20}) in patients receiving mastectomy alone than those who received breast conservation. Other correlates of lower satisfaction were chemotherapy receipt, higher BMI, smoking, and lower family income. As Figure 2 details, on the five-point Satisfaction with Breast Cosmetic Outcomes scale, the adjusted scaled satisfaction score was 3.4 for patients receiving breast conservation, 3.6 for those receiving mastectomy with autologous reconstruction, 3.3 for patients receiving mastectomy with implant reconstruction, and 3.0 for patients receiving mastectomy without reconstruction.

Table 3. Linear Regression Model of Satisfaction with Breast Cosmetic Outcomes* (n=1245**).

| Characteristic | Estimated Coefficient | Standard Error | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.41 | 0.13 | (3.15, 3.67) | <0.001 |

| Surgical treatment | 0.0002 | |||

| Mastectomy without Reconstruction | -0.38 | 0.093 | (-0.56, -0.20) | |

| Mastectomy with Autologous Reconstruction | 0.21 | 0.16 | (-0.093, 0.52) | |

| Mastectomy with Implant Reconstruction | -0.12 | 0.13 | (-0.38, 0.14) | |

| Breast conservation | 0 | 0 | (0, 0) | |

| Chemotherapy | -0.16 | 0.071 | (-0.30, -0.017) | 0.028 |

| BMI*** | -0.027 | 0.006 | (-0.038, -0.016) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking | -0.26 | 0.11 | (-0.46, -0.048) | 0.016 |

| Age**** | 0.003 | 0.003 | (-0.004, 0.010) | 0.42 |

| Education | 0.23 | |||

| High School or less | -0.14 | 0.093 | (-0.33, 0.038) | |

| Some College | -0.11 | 0.082 | (-0.28, 0.049) | |

| College or more | 0 | 0 | (0, 0) | |

| Race | 0.093 | |||

| White (non-Latina) | 0 | 0 | (0, 0) | |

| Black | 0.20 | 0.084 | (0.039, 0.37) | |

| Latina (English-speaking) | 0.015 | 0.097 | (-0.18, 0.21) | |

| Latina (Spanish-speaking) | 0.010 | 0.12 | (-0.22, 0.24) | |

| Family Income at Diagnosis | 0.011 | |||

| <$20,000 | 0 | 0 | (0, 0) | |

| $20,000-$70,000 | 0.20 | 0.11 | (-0.023, 0.43) | |

| >$70,000 | 0.054 | 0.13 | (-0.19, 0.30) | |

| unknown | 0.34 | 0.13 | (0.092, 0.60) |

Satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes was measured by an interval scale derived the mean of 6 items, as described more fully in the methods section. Mean (SD) of the scale was 3.33 (1.02), with a minimum of 1 and maximum of 5. Cronbach's alpha was 0.90.

measured in all patients but 205 patients were not included because of missing values either in dependent or independent variables

BMI centered about 30, such that every one-unit increase in BMI results in an average of a 0.02 unit decrease in satisfaction, and each one-unit decrease BMI below 20 results in a 0.02 unit increase in satisfaction

Age centered about 60, such that every one-year increase in age results in an average of a 0.003 unit increase in satisfaction, and each one year decrease in age below 60 results in a 0.003 unit decrease in satisfaction

Figure 2. Satisfaction with Breast Cosmetic Outcomes by Surgery Type.

This figure depicts adjusted scores on the scaled measure of satisfaction with breast cosmetic outcomes by type of surgery received, based on results from the model described in Table 3. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals in comparison to the reference group (breast conserving therapy). Satisfaction with breast cosmetic outcomes was measured by an interval scale derived the mean of 6 items, as described more fully in the methods section. Mean (SD) of the scale was 3.33 (1.02), with a minimum of 1 and maximum of 5. Cronbach's alpha was 0.90.

Of the 222 patients who received mastectomy and reconstruction, 200 had complete variable information and were further evaluated. There were 53 patients who had RT (among whom 54% had autologous technique and 48% had delayed timing of reconstruction) and 147 who did not (among whom 23% had autologous technique and 29% had delayed timing).

Table 4 presents a linear regression model of the scaled measure of Satisfaction with Reconstruction Outcomes in patients who received mastectomy and reconstruction. We observed a substantial and statistically significant difference among four groups formed by type of reconstruction procedure and receipt of radiation. In particular, patients who received implants with radiation had a markedly lower satisfaction than all other subgroups. The pattern across subgroups also suggested that satisfaction was higher for patients who received autologous reconstruction and those who did not receive radiation. As Figure 3 details, on the five-point Satisfaction with Reconstruction Outcomes scale, the adjusted scaled satisfaction score was 4.7 for patients receiving autologous reconstruction without radiation, 4.4 for patients receiving autologous reconstruction and radiation therapy, 4.1 for patients receiving implant reconstruction without radiation, and 2.8 for patients receiving implant reconstruction and radiation therapy. Thus, patients who received radiation and implant-based reconstruction had significantly lower satisfaction than the other three groups (those who received implant reconstruction without radiation, and those undergoing autologous reconstruction, with or without radiation). We observed no significant association between timing of reconstruction and satisfaction with reconstruction outcomes, nor did we observe a significant interaction between timing and radiation receipt.

Table 4. Linear Regression Model of Satisfaction with Reconstruction Outcomes* (n=200**).

| Characteristic | Estimated Coefficient | Standard Error | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.10 | 0.40 | (3.30, 4.89) | <0.001 |

| Reconstruction Type and Radiation Status | <0.001 | |||

| Autologous no radiation | 0.63 | 0.24 | (0.16, 1.11) | |

| Autologous with radiation | 0.29 | 0.27 | (-0.24, 0.82) | |

| Implant no radiation | 0 | 0 | (0, 0) | |

| Implant with radiation | -1.32 | 0.34 | (-1.99, -0.65) | |

| Reconstruction timing | 0.997 | |||

| Immediate | 0.00 | 0 | (0, 0) | |

| Delayed | 0 | 0.22 | (-0.43, 0.43) | |

| Age*** | -0.03 | 0.01 | (-0.05, -0.01) | 0.015 |

| Married/partnered | -0.47 | 0.20 | (-0.86, -0.07) | 0.021 |

| Education | 0.314 | |||

| High School or less | -0.26 | 0.24 | (-0.73, 0.22) | |

| Some college | -0.33 | 0.22 | (-0.76, 0.11) | |

| College or more | 0 | 0 | (0, 0) | |

| Insurance | 0.033 | |||

| Medicare | 0.83 | 0.62 | (-0.38, 2.05) | |

| Medicaid | -1.18 | 0.57 | (-2.30, -0.06) | |

| Other | -0.25 | 0.28 | (-0.80, 0.30) | |

| None | 0 | 0 | (0, 0) |

Satisfaction with reconstruction outcomes was measured by an interval scale derived the mean of 5 items, as described more fully in the methods section. Mean (SD) of the scale was 3.64 (1.27), with a minimum of 1 and maximum of 5. Cronbach's alpha was 0.91.

Measured in patients who received breast reconstruction; 22 patients were not included because of missing values in dependent or independent variables

Age centered about 60, such that every one-year increase in age results in an average of a 0.02 unit decrease in satisfaction, and each one year decrease in age below 60 results in a 0.02 unit increase in satisfaction

Figure 3. Satisfaction with Outcomes of Breast Reconstruction by Reconstruction Type and Receipt of Radiation Therapy*.

This figure depicts adjusted scores on the scaled measure of satisfaction with reconstruction outcomes, as measured in patients receiving breast reconstruction with various approaches, based on results from the model described in Table 4. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals in comparison to the reference group (implant no radiation). Satisfaction with reconstruction outcomes was measured by an interval scale derived the mean of 5 items, as described more fully in the methods section. Mean (SD) of the scale was 3.64 (SD 1.27), with a minimum of 1 and maximum of 5. Cronbach's alpha was 0.91.

Discussion

In this large sample of breast cancer survivors identified through metropolitan population-based registries, we found that QOL and long-term satisfaction with the cosmetic outcome of breast cancer treatment overall was quite high. Breast reconstruction resulted in a level of patient-reported satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes in patients undergoing mastectomy that was statistically indistinguishable from that of patients who received breast conserving therapy. Among patients undergoing breast reconstruction, satisfaction with outcomes of reconstruction at four years was higher in patients receiving autologous reconstruction and lower in patients receiving post-mastectomy radiation therapy. Moreover, the differences in satisfaction between the locoregional treatment subgroups post-mastectomy were substantial: patients who received autologous reconstruction without radiation reported on average that they were very satisfied (score 4.7/5); while those who received implants with radiation reported on average that they were dissatisfied (score 2.8).

Previous studies, primarily conducted in centers of excellence or in the context of clinical trials, have suggested that the vast majority of patients treated with breast-conserving therapy in those settings have good or excellent cosmetic outcomes.19 The aesthetic results of breast conservation reflect the size and location of the surgical defect and scar, as well as late radiation changes to the skin. 20-22 Breast edema, which results from both surgery and radiation therapy, resolves in time for most patients, but may persist for years.23,24 Fibrosis, again due to the interplay of surgical wound healing and reaction to radiotherapy, tends to manifest 6-18 months after treatment and may progress over time.25 In patients who do experience significant asymmetry as a result of such changes, QOL has been shown to be reduced.26 Therefore, we found it particularly important in the current study to document the patient-reported QOL and cosmetic outcomes in a population of survivors treated in a broader variety of settings, at a time point after acute post-treatment changes have resolved. Our findings of high patient-reported satisfaction and few differences in QOL in this context are reassuring and do not support the notion that the recently observed increases in the rates of bilateral mastectomy for unilateral cancer are justified by poor cosmetic outcome after breast-conserving therapy.

Our findings that the outcomes of breast reconstruction are similar to those of breast conservation, as experienced by patients treated in a variety of settings within two large and diverse metropolitan regions of the United States, are also reassuring. These findings complement existing literature seeking to identify best practices and approaches towards reconstruction. For example, in one of the only multi-center studies of reconstruction outcomes reported from a U.S. sample, aesthetic satisfaction at two years was higher in patients who had received autologous tissue-based reconstruction rather than implant techniques,27 and these differences appeared to increase over time.28 Our findings support the idea that the use of autologous techniques for reconstruction is associated with improved satisfaction. Additionally, in a population where a minority of women had contralateral prophylactic mastectomy, the high level of satisfaction with cosmetic outcome and lack of significant association between receipt of bilateral mastectomy and satisfaction support the findings of a single institution patient survey, in which no differences in satisfaction were observed between patients undergoing unilateral and bilateral mastectomy,29 suggesting that contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is not necessary to achieve a good cosmetic outcome with breast reconstruction.

The impact of radiation therapy on breast reconstruction is a subject of considerable interest.30,31 Radiation toxicity, including skin changes, vascular compromise, and fibrosis, can compromise the viability and cosmesis of the reconstruction and may require repeated intervention for correction. Previous retrospective studies have suggested that regardless of the type of reconstruction, radiation compromises cosmetic outcomes.32-37 Our results support this idea but also suggest that autologous techniques may mitigate some of the deleterious impact of radiotherapy on cosmetic outcomes. Taken together, this evidence supports counseling women in whom it is evident at the time of initial surgical evaluation that postmastectomy radiotherapy is likely to be necessary (those with a larger primary tumor or clinically positive nodes) about the potential for a suboptimal cosmetic outcome with reconstruction under this clinical scenario. Those who are candidates for breast conservation may reasonably choose to pursue that option instead.

The optimal approach to breast reconstruction in patients who do receive mastectomy and require postmastectomy radiotherapy for disease control continues to generate debate.38 Complications in implant patients who receive radiotherapy include scarring, capsular contracture, infection, pain, skin necrosis, fibrosis, and impaired wound healing.32-35 Still, some institutions have reported excellent results using relatively uniform and carefully controlled approaches towards implant reconstruction in the setting of radiotherapy.39,40 Women undergoing radiation after autologous reconstruction face increased risks of fat necrosis, fibrosis, atrophy, and flap contracture.36,37 However, some clinicians believe that patients receiving radiation may have better outcomes after autologous reconstruction than after implants41 and have demonstrated good outcomes with such approaches.42 However, estimates of the frequency of complications with different techniques and different sequences of radiation and reconstructive procedures have varied widely between different institutional series, and there is considerable need for patient-reported outcomes data from patients treated across practices in the community. The current study begins to address this need, and its findings suggest that autologous approaches may indeed be superior in patients who receive radiotherapy. Its findings also suggest, consistent with other studies on utilization of reconstruction,43 that autologous techniques may be utilized more frequently in radiated than unirradiated patients, but a substantial proportion of radiated patients do receive implants.43

Nevertheless, it is also important to consider limitations of this study. Of note, the number of patients who received reconstruction in this sample was substantial but not extremely large. Therefore, the lack of an observation of a statistically significant interaction between radiation receipt and timing of reconstruction is not evidence of absence of such an effect. Given the sample size, the power to detect interaction effects was limited, and there may well be a differential impact of reconstruction timing in radiated patients that this study was unable to detect. This does not, however, undercut the importance of findings such as the positive effect of autologous reconstruction on satisfaction, particularly in patients receiving radiotherapy. Still, given the number of patients receiving breast reconstruction in the overall sample, additional studies should be conducted to further validate these results. It is also important to note that as in all observational studies, associations may not indicate causation; however, given the impracticality of randomized trials to investigate these issues in the modern era, careful observational analysis may nevertheless yield insights. We have taken care to consider potential confounding factors, as well as to obtain responses from a broad and more generalizable population than that achieved in single institution studies. We cannot, however, control for the possibility that women electing breast reconstruction may have had greater baseline dissatisfaction with their breast size or shape.

In sum, the findings of the current study provide reassuring evidence that QOL and satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes among breast cancer survivors overall is high. These results suggest that breast reconstruction allows patients undergoing mastectomy to have long-term satisfaction similar to that of patients undergoing breast conservation. Our findings regarding the deleterious impact of radiation on satisfaction after breast reconstruction may have implications for patient decision-making, and the potential impact of autologous reconstruction in mitigating this effect merits further confirmation in independent, multicenter datasets. Patients' decisions about whether to pursue reconstruction, as well as the specific type and timing of reconstruction, should ideally be informed by rigorous, multicenter outcomes data like those provided in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclaimers: This work was funded by grants R01 CA109696 and R01 CA088370 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the University of Michigan. Dr. Jagsi was supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society (MRSG-09-145-01). Dr. Katz was supported by an Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral, and Population Sciences Research from the NCI (K05CA111340).

The collection of LA County cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the NCI's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program under contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, contract N01-PC-54404 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement 1U58DP00807-01 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The collection of metropolitan Detroit cancer incidence data was supported by the NCI SEER Program contract N01-PC-35145. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

We acknowledge the outstanding work of our project staff: Barbara Salem, MS, MSW, and Ashley Gay, BA (University of Michigan); Ain Boone, BA, Cathey Boyer, MSA, and Deborah Wilson, BA (Wayne State University); and Alma Acosta, Mary Lo, MS, Norma Caldera, Marlene Caldera, and Maria Isabel Gaeta, (University of Southern California). All of these individuals received compensation for their assistance.

We thank the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (David Winchester, MD, and Connie Bura) and the National Cancer Institute Outcomes Branch (Neeraj Arora, PhD, and Steven Clauser, PhD) for their support.

We acknowledge with gratitude the breast cancer patients who responded to our survey.

References

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer: An overview of the randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1444–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511303332202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrow M, Jagsi R, Alderman AK, et al. Surgeon recommendations and receipt of mastectomy for treatment of breast cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:1551–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire KP, Santillan AA, Kaur P, et al. Are mastectomies on the rise? A 13-year trend analysis of the selection of mastectomy versus breast conservation therapy in 5865 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2682–2690. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0635-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katipamula R, Degnim AC, Hoskin T, et al. Trends in mastectomy rates at the Mayo Clinic Rochester: effect of surgical year and preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4082–4088. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuttle TM, Habermann EB, Grund EH, et al. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5203–5209. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portschy PR, Tuttle TM. Rise of mastectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:563–564. doi: 10.1002/jso.23340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klassen AF, Pusic AL, Scott A, et al. Satisfaction and quality of life in women who undergo breast surgery: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olivotto IA, Whelan TJ, Parpia S, et al. Interim cosmetic and toxicity results from RAPID: a randomized trial of accelerated partial breast irradiation using three-dimensional conformal external beam radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4038–4045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norris D, Julian TB. Update on the NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413 Clinical Trial Comparing Partial to Whole Breast Irradiation Therapy. Oncology Issues. 2008:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenhalgh J, Meadows K. The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: a literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 1999;5:401–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.1999.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cano SJ, Klassen A, Pusic A. The science behind quality-of-life measurement: a primer for plastic surgeons. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:98e–106e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819565c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cano SJ, Klassen AF, Scott AM, et al. A closer look at the BREAST-Q. Clin Plast Surg. 2013;40:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanton AL, Krishnan L, Collins CA. Form or function? 1. Subjective cosmetic and functional correlates of quality of life in women treated with breast-conserving surgical procedures and radiotherapy. Cancer. 2001;91:2273–2281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan L, Stanton AL, Collins CA, et al. Form or function? 2. Objective cosmetic and functional correlates of quality of life in women treated with breast-conserving surgical procedures and radiotherapy. Cancer. 2001;91:2282–2287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alderman AK, Kuhn LE, Lowery JC, et al. Does patient satisfaction with breast reconstruction change over time? Two-year results of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, et al. Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: Population-based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2022–2029. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grovers RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, et al. Survey methodology. 2nd. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurtz JM. Impact of radiotherapy on breast cosmesis. Breast. 1995;4:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bentzen SM, Thames HD, Overgaard M. Latent-time estimation for late cutaneous and subcutaneous radiation reactions in a single-follow-up clinical study. Radiother Oncol. 1989;15:267–274. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(89)90095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bentzen SM, Turesson I, Thames HD. Fractionation sensitivity and latency of telangiectasia after postmastectomy radiotherapy: A graded response analysis. Radiother Oncol. 1990;18:95–106. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(90)90135-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turesson I. The progression rate of late radiation effects in normal tissue and its impact on dose-response relationships. Radiother Oncol. 1989;15:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(89)90089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke D, Martinez A, Cox RS, et al. Breast edema following staging axillary node dissection in patients with breast carcinoma treated by radical radiotherapy. Cancer. 1982;49:2295–2299. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820601)49:11<2295::aid-cncr2820491116>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose MA, Olivotto I, Cady B, et al. Conservative surgery and radiation therapy for early breast cancer: Long-term cosmetic results. Arch Surg. 1989;124:153–157. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410020023002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris JR, Levene MB, Svensson G, et al. Analysis of cosmetic results following primary radiation therapy for stage 1 and stage 2 carcinoma of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5:257–261. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(79)90729-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waljee JF, Hu ES, Ubel PA, et al. Effect of esthetic outcome after breast-conserving surgery on psychosocial functioning and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3331–3337. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alderman AK, Kuhn LE, Lowery JC, et al. Does patient satisfaction with breast reconstruction change over time? Two-year results of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu ES, Pusic AL, Waljee JF, et al. Patient-reported aesthetic satisfaction with breast reconstruction during the long-term survivorship Period. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1–8. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ab10b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craft RO, Colakoglu S, Curtis MS, et al. Patient Satisfaction in unilateral and bilateral breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1417–1424. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318208d12a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kronowitz S. Current Status of implant-based breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:513e–523e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318262f059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kronowitz S. Current status of autologous tissue-based breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:282–292. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182589be1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krueger EA, Wilkins EG, Strawderman M, et al. Complications and patient satisfaction following expander/implant breast reconstruction with and without radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:713–721. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Contant CME, van Geel AN, van der Holt B, et al. Morbidity of immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) after mastectomy by a subpectorally placed silicone prosthesis: the adverse effect of radiotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:344–350. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tallet AV, Salem N, Moutardier V, et al. Radiotherapy and immediate two-stage breast reconstruction with a tissue expander and implant: Complications and esthetic results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:136–142. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ascherman JA, Hanasono MM, Newman MI, et al. Implant reconstruction in breast cancer patients treated with radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:359–365. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000201478.64877.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams JK, Carlson GW, Bostwick J, et al. The effects of radiation treatment after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:1153–1160. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199710000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers NE, Allen RJ. Radiation effects on breast reconstruction with the deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1919–1924. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200205000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alderman AK, Jagsi R. Discussion: Immediate post-mastectomy breast reconstruction followed by radiotherapy: risk factors for complications. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:635–637. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0878-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho A, Cordeiro P, Disa J, et al. Long-term outcomes in breast cancer patients undergoing immediate 2-stage expander/implant reconstruction and postmastectomy radiation. Cancer. 2012;118:2252–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kronowitz SJ, Lam C, Terefe W, et al. A multidisciplinary protocol for planned skin-preserving delayed breast reconstruction for patients with locally advanced breast cancer requiring postmastectomy radiation: 3-year follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2154–2166. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182131b8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chawla A, Kachnic L, Taghian A, et al. Radiotherapy and breast reconstruction: complications and cosmesis with TRAM versus tissue expander/implant. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:520–26. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02951-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang EI, Liu TS, Festekjian JH, et al. Effects of radiation therapy for breast cancer based on type of free flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:1e–8e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729d33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jagsi R, Jiang J, Momoh A, et al. Trends and Variation in Use of Breast Reconstruction in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Mastectomy in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:919–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.