Abstract.

Our understanding of neural information processing could potentially be advanced by combining flexible three-dimensional (3-D) neuroimaging and stimulation. Recent developments in optogenetics suggest that neurophotonic approaches are in principle highly suited for noncontact stimulation of network activity patterns. In particular, two-photon holographic optical neural stimulation (2P-HONS) has emerged as a leading approach for multisite 3-D excitation, and combining it with temporal focusing (TF) further enables axially confined yet spatially extended light patterns. Here, we study key steps toward bidirectional cell-targeted 3-D interfacing by introducing and testing a hybrid new 2P-TF-HONS stimulation path for accurate parallel optogenetic excitation into a recently developed hybrid multiphoton 3-D imaging system. The system is shown to allow targeted all-optical probing of in vitro cortical networks expressing channelrhodopsin-2 using a regeneratively amplified femtosecond laser source tuned to 905 nm. These developments further advance a prospective new tool for studying and achieving distributed control over 3-D neuronal circuits both in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: optogenetics, spatial light modulator, two-photon microscopy, temporal focusing

1. Introduction

Complementary information regarding the dynamics and functional connectivity of neural networks can be obtained by combining the monitoring of natural/spontaneous neural activity patterns with induced activity perturbations.1–3 In this context, parallel “optical” monitoring and stimulation techniques have significant advantages over electrical methods since larger cellular populations can be monitored simultaneously and flexible single-cell targeted stimulation inside a three-dimensional (3-D) network can be achieved using a single experimental setup.1,4,5 Indeed, several studies have demonstrated combined imaging and photostimulation using either glutamate uncaging6–9 or optogenetic excitation.1,10–12 However, a comprehensive 3-D all-optical solution for bidirectional probing of neural networks has yet to emerge and requires a combined solution to challenges in the selection of the imaging and stimulation probes and in the design of a suitable optical system.

Optogenetic excitation has multiple major advantages over uncaging in 3-D cell-targeted stimulation,13 and therefore combining optogenetic actuators like channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) with an orthogonal (cross-talk free) activity indicator is of particular significance in this context. Guo et al.10 report that despite the spectral overlap between the excitation of ChR2 and the GFP based genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) such as GCaMP-type probes, all-optical stimulation and recording can be achieved using low-intensity background illumination. Hochbaum et al.11 introduce the powerful orthogonal optogenetic probe combination of the voltage indicators QuasAr1/2 and the actuator CheRiff, for combined high-rate two-dimensional (2-D) voltage imaging and excitation (and closed-loop optopatching), but scaling it to 3-D networks while preserving the high temporal resolution is challenging. Precise optogenetic stimulation of neurons inside dense 3-D networks requires spatially confined illumination of cells, which cannot generally be achieved with single-photon methods, whereas direct multiphoton excitation requires tight spatial focusing; applying this excitation spot across a cell’s membrane is achieved through scanning and limits the temporal controllability.12,14,15 Temporally focused (TF) nonlinear microscopy provides the ability to generate optically sectioned illumination of thin planes,6,16 lines,17,18 or flexible patterns5,19,20 inside a 3-D volume without the need for such tight spatial focusing. TF is typically obtained by placing a diffraction grating at a plane conjugate to the system’s focal plane. Consequently, the laser pulse’s duration is manipulated, rather than its spatial dimensions, allowing the decoupling of the lateral and axial dimensions of the illuminated beam. TF can be applied for either imaging or stimulation: in both modalities, large-area illumination can eliminate the need for scanning and can significantly improve the temporal characteristics with a minimal decrease in spatial resolution. Projected TF stimulation light discs1,4 and patches5 were thus applied for two-photon (2P) optogenetic stimulation, and recently, multiphoton microscopes were introduced where TF illumination lines21 or planes22 from a femtosecond laser “amplifier” were used for optically sectioned volumetric imaging of extended 3-D optically accessible networks.

Here, we aim to advance toward realizing the potential of this technological approach in a “bidirectional” optical neural interface, by integrating a hybrid multiphoton-TF system for 3-D holographic optical neural stimulation (HONS) into a recently introduced volumetric imaging hybrid microscope;21 both subsystems utilize an amplified femtosecond laser source and are based on the same design strategy, which is described in Sec. 2. We next use a screening system with combined electrical and optical recording capabilities (Sec. 3) to examine the effective crosstalk between candidate probe-indicator pairs that could potentially facilitate all-optical bidirectional optophysiology. In the probe screening experiments (Sec. 4.1), we find that whereas we could not effectively combine ChR2 and GCaMP-type probes as suggested by Guo et al.,10 spectral independence is obtained between ChR2 and the red organic calcium dye Rhod-2 (excitation peak at 552 nm). In Sec. 4.2, we use ChR2 and Rhod-2 to demonstrate cell-targeted 2P holographic excitation in a network of cortical cells and then experimentally explore, in Sec. 4.3, the generation of cell-matched excitation patterns using the TF mode of our hybrid holographic system. The approach’s prospects and current technical limitations are discussed in Sec. 5.

2. Optical System

2.1. Design of Hybrid Multiphoton Holographic Stimulation and Imaging System

Our approach toward a bidirectional optophysiological system is based on expanding a recently introduced hybrid multiphoton TF microscope, which can volumetrically record neural activity using calcium sensitive dyes,21 to also enable precise 2-D or 3-D optogenetic stimulation of neuronal networks. The hybrid microscope uses light from a regeneratively amplified ultrafast laser (RegA 9000, Coherent) and combines a scanning line TF mode with standard point-by-point 2P laser scanning microscopy. For targeted photostimulation, a HONS subsystem based on a phase-only spatial light modulator (SLM) was added [Fig. 1(a)], and the RegA wavelength was custom-switched from 800 to 905 nm,23 closer to the 2P excitation peak of ChR2.4,14 Both the hybrid microscope and the new hybrid 2P HONS subsystem use the same optical element, a dual prism grating (DPG or grism), in order to generate optically sectioned TF illumination patterns, while allowing an easy switch to a non-TF mode. The DPG is a custom transmissive diffraction grating mounted between two prisms and has three fundamental advantages over standard blazed gratings, which are usually used for TF. First, it can be easily placed in the optical path with minimal changes, since the diffracted light passing through the DPG continues to propagate along the original optical axis. Second, the DPG enhances diffraction efficiency (85% in our setup) relative to reflective diffraction gratings (typically 50% to 70%) accommodating for the limitation on the holographic projection system imposed by the pulse energy. Third, a DPG-based TF setup enables remote scanning of the focal plane,24 thus allowing an independent axial movement of the imaging and stimulation modules.

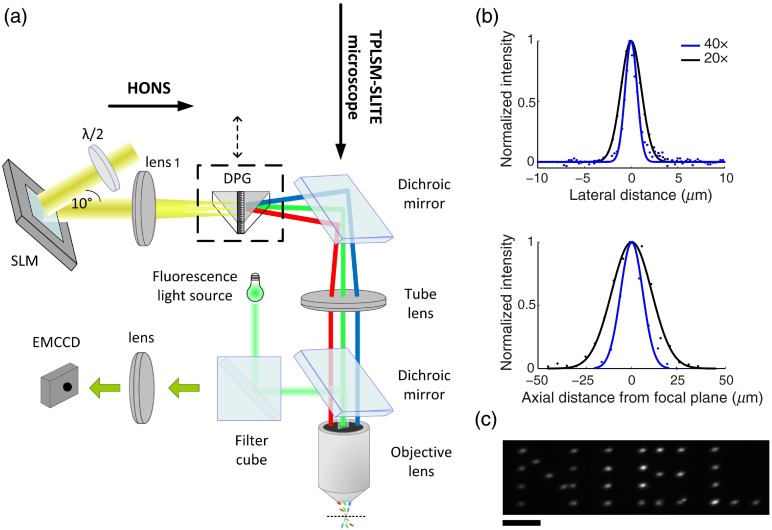

Fig. 1.

Hybrid-multiphoton holographic stimulation and imaging system. (a) Optical scheme shows the optical arrangement of the two-photon holographic optical neural stimulation (2P-HONS) subsystem and its integration with the hybrid multiphoton microscope, whose EMCCD camera can also be used with a fluorescence light source for conventional single-photon imaging. The dual prism grating provides the HONS system with an optional temporal focusing (TF) mode. (b) System’s resolution for single spot generation (w/o TF) shown as lateral and axial projected point spread function’s (PSF) cross-sections with full width at half maximum dimensions of laterally and axially, and (lateral) and (axial), for the and objective lenses, respectively. Dots and lines represent the raw measured data and Gaussian fits, respectively. (c) Holographically generated two-dimensional (2-D) light pattern projected onto a fluorescein film through a objective [neural interface engineering lab (NIEL)—lab initials]. Scale bar: .

For identical average powers, an amplified laser enhances 2P absorption by a factor inversely proportional to the pulsed laser’s duty cycle25 (product of pulse duration and repetition rate): compared to a standard Ti:Sapphire laser operating at a repetition rate of , an amplified laser that has roughly the same pulse duration () but a repetition rate of provides an expected excitation gain factor of (excluding saturation effects). In HONS and TF, this gain in efficiency can be used to mitigate the effect of reducing the beam’s intensity by splitting it and increasing its focal diameter. However, due to the technical issues involved in switching the RegA laser wavelength from 800 to 905 nm, the modified laser generates pulses with an extended duration () and reduced average power output ( at 150 KHz) in comparison to its 800-nm design wavelength (600 mW at 150 KHz), which was further attenuated to near the objective focal plane mainly due to the SLM’s relatively low efficiency. To allow the entire laser power to be directed toward each of the subsystems, a flip mirror (not shown) enables an easy switch between the two setups; to maintain the ability to image the holographically stimulated networks’ responses in 2-D cultured cells with the ability to flexibly change the imaged wavelengths, a wide-field epifluorescence illumination path (single-photon) was integrated into the system: light from fiber illumination source (Intensilight, Nikon) was transmitted through a designated filter cube, which was replaced according to spectral specifications of the imaged fluorescent probe. Light was reflected to and from the sample by a dichroic mirror placed above the objective lens. The emitted fluorescence from the sample was detected by an electron multiplying charge coupled device (EMCCD, Andor, front-illuminated iXon DU-885, 1Mpixels, max full resolution frame rate: 31 fps).

In the HONS optical path, a collimated beam from the RegA laser passes through a Pockels cell (Conoptics, model 350-801A) for power modulation and is then expanded by a beam expander (6x) to match the laser beam cross-section to the input aperture of a liquid crystal on silicon-SLM (X10468-02, Hamamatsu), which operates in reflection mode. This nematic SLM has a resolution of extending over an area of , with 256 phase gray levels and a 95% fill factor. A half-wave plate was placed between the beam expander and the SLM to horizontally polarize the input light in order to optimize the modulation performance, and to minimize the system’s distortion, the angle between the SLM’s input and output beams was minimized (). A telescope ( and ) was used to image the SLM aperture to the rear aperture of the objective lens; the telescope’s magnification, , was chosen to fully utilize the objective lens’ numerical aperture (NA). An enlarged replica of the target hologram was obtained in the focal plane of (which is conjugated to the focal plane of the objective lens) and was used for filtering unwanted diffraction orders or other manipulations of the holograms. Specifically, a beam block made of a tin dot was used to physically block the zero order spot. The custom DPG (Wasatch Photonics) is optionally introduced in the focal plane of for obtaining TF and consists of a transmission diffraction grating () mounted between two prisms (, BK7 glass).

An objective lens and tube lens mounted in a configuration image the hologram generated by the SLM onto the objective focal plane, where a 2P holographic pattern is obtained. With the DPG introduced (TF mode), the first plane is on the grating’s surface and a TF pattern is obtained in the objective’s focal plane. The system was characterized (and applied here) using two water immersion objective lenses: a 0.8 NA lens (Nikon) and a 0.5 NA lens (Olympus), resulting in respective projection field dimensions of and . Without the DPG installed into the optical path, the PSF full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) dimensions are laterally and axially, and (lateral) and (axial), for the and objective lenses, respectively [Fig. 1(b)]. Note that due to underfilling of the objective lens, the effective NA is and , respectively. This underfilling enables a wider scan range and the use of fewer and larger spots for each holographic patch. Using a flexible graphical user interface based software which implements the weighted Gerchberg–Saxton (GSW) algorithm,26 the holographic system is capable of generating flexible multispot holographic patterns [Fig. 1(c)], which can be dynamically updated at rates up to the SLM’s refresh rate of .

2.2. Hologram Calibration and Calculation Process

The stimulation and imaging fields of view (FOVs) were calibrated to match the location of the excitation patterns’ coordinates to the neurons’ image locations using the following equation:

| (1) |

where and are the stimulation field and the imaging FOV coordinates, respectively, is a constant matrix, and is a constant shift. A calibration pattern consisting of four spots at known locations in the SLM stimulation field was projected on a thin layer of fluorescein in the sample plane. The corresponding spots’ locations were marked in the imaged FOV and used to solve the equation and deduce for each the corresponding target coordinates.

Calibrated holograms were calculated using GSW algorithm,26 which produces holograms with high efficiency and uniformity but is relatively computationally demanding. We set the convergence values for efficiency and uniformity to 0.95 and limited the number of iterations to 10 to shorten the calculation time. Compensation over distortion caused by the SLM lack of flatness was done by adding a flatness correction phase to the projected computer generated holograms (CGHs), supplied by the SLM manufacturer.

The CGHs were controlled by MATLAB®-based psychophysics toolbox27 and sent to the SLM via a digital video interface at a refresh rate of 60 Hz. The SLM was synchronized with other equipment by splitting the video output to an additional display and by using a photodiode to detect the illumination changes on the screen. This signal was used for recording of actual holograms’ timing.

3. Experimental Methods

3.1. Preparation, Transfection, and Staining of Cortical Neural Cultures

Cortices were extracted from anesthetized P0 Sprague–Dawley rats, dissected in phosphate-buffered saline glucose and incubated with trypsin for 10 min. Trypsin proteolytic activity was stopped by the addition of horse serum. Cells were separated from the tissue by gentle trituration with a pipette, filtered, and isolated by centrifugation. Cells were resuspended in planting medium, cells were planted on each cover glass/multielectrode array (MEA) coated with polyethyleneimine. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 95% air, 5% humidified incubator, and culture media was replaced twice a week. Cultures were used after .

Viral transfection of neural cultures with optogenetic actuators/indicators was done 1 day after cell planting by application of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector carrying the gene of interest under the control of a neuron specific promoter, usually synapsin (UPENN). Specifically: ChR2-mCherry [AAV9.CAG.hChR2(H134R)-mCherry.WPRE.SV40], ChR2-YFP [AAV9.hSyn.hChR2(H134R)-eYFP.WPRE.hGH], and GCaMP3 [AAV1.hSyn.GCaMP3.WPRE.SV40]. Concentrations of AAV vectors added to the culturing medium were as follows: 0.25 to for GCaMP3, 1 to for ChR2-mCherry, and for ChR2-eYFP.

For calcium imaging using red-shifted organic indicator Rhod-2 AM (Invitrogen), at the day of the experiment, cell cultures were incubated with the indicator (2 to of a solution) for 45 min, at 37°C, 5% humidified incubator. Afterward, the medium was replaced with dye-free culture medium.

3.2. Probe Screening Experiments

Probe screening experiments were performed in a single-photon holographic stimulation system. Detailed description of this optical setup and data analysis methods applied in experiments using optical and electrical simultaneous recordings can be found in Golan et al.28 and Reutsky-Gefen et al.29 Briefly, to stimulate ChR2-expressing neurons, wide-field blue light flashes were delivered with a laser coupled to an optic fiber (Thorlabs, in diameter, 473 nm, 2 to ). Calcium single-photon imaging was done using a CCD camera (Hamamatsu C8484-05G, Japan) at . Initial recordings of GCaMP3 calcium traces resulting from driving ChR2-expressing neurons were done using a GFP filter set (XF100-2, Omega), which was later changed to modified Texas Red filter set for Rhod-2 calcium indicator imaging (570Ex/625Em, Nikon, with excitation filter replaced to HQ580/13x, Chroma).

3.3. Multiphoton HONS Characterization Measurements

Measurements of the spots’ lateral and axial resolution were done by projecting a single spot (or several spots) on a thin layer of fluorescein (FLUKA Fluorescein sodium salt, Sigma-Aldrich). The spot’s lateral resolution was calculated from the spot’s intensity lateral cross-section, which was fitted to a Gaussian curve and used to calculate the FWHM of the fitted intensity. The spot’s axial sectioning, which determined the system’s axial resolution, was calculated by measuring the spot’s intensity at different axial locations by an additional epifluorescence detection path (using a uEye camera, IDS), situated beneath the fluorescent sample. The sample and the second objective lens were mounted on two micromanipulators (MP-285 and MP-225, respectively, Sutter), which were used to move the sample and the detection system to controlled distances from the upper objective lens’ focal plane. The spot’s average intensity was calculated for images taken at different distances and fitted to a square-root of a Lorentzian curve. The FWHM of the fitted intensity was calculated.

3.4. All-Optical Probing Experiments and Calcium Movie Analysis

Cells were first imaged to identify ChR2-eYFP-expressing cells. When using holographic targeting, we manually chose the cells we would like to target inside the accessible stimulation field and calculated the matching holograms. The excitation locations were saved for later recognition of stimulated cells during data analysis. Stimulation occurrences and pulse durations were also saved. Calcium responses elicited by ChR2 stimulation were optically recorded by an EMCCD camera at . The fluorescence signals of selected neurons were extracted from the movies by calculating the mean pixel intensity over a radius of around the neurons’ locations for the different time points and subtracting the dark current values. These fluorescent signals were normalized according to

| (2) |

where is each cell’s average signal during the experiment’s first 30 s and is its temporal fluorescence signal. The stimulation artifacts, i.e., frames saturated by the high intensity flashes during the ChR2 stimulation period, have been removed, and their timings were used to identify the exact frames in which the stimulation has occurred [marked by arrows in Figs. 2(c), 3(b), and 3(c)]. We minimized the stimulus duration to reduce the amount of frames that saturate per stimulus.

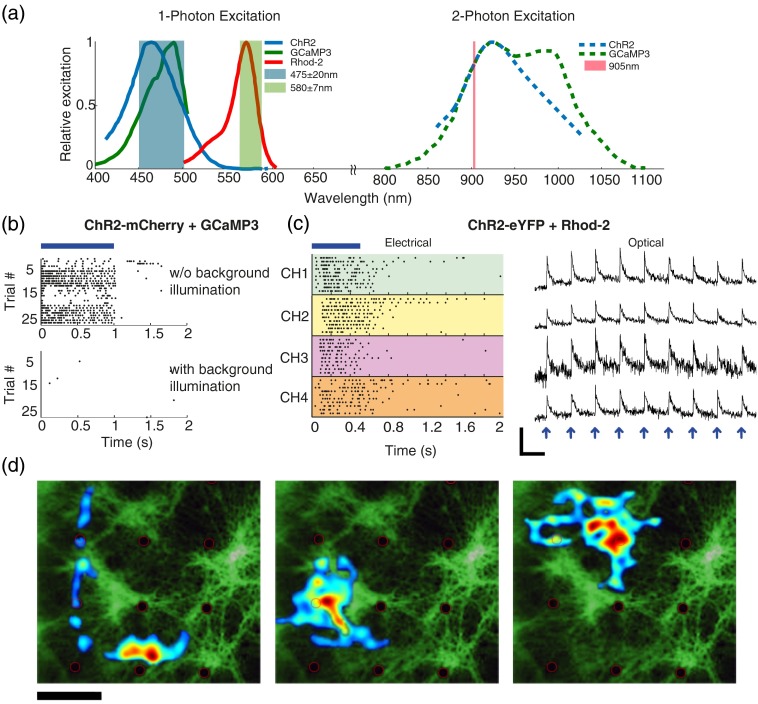

Fig. 2.

Selection of optical indicators for imaging stimulated channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2)-expressing neurons. (a) Left: ChR2, GCaMP3, and Rhod-2 single-photon excitation spectra with overlaid excitation filter bandwidths. The wavelength overlap between ChR2 and GCaMP3 (GFP filter cube, light blue) makes simultaneous stimulation challenging, whereas Rhod-2 excitation can be easily spectrally separated using appropriate filters (green shaded region). Right: ChR2 and GCaMP3 2P excitation spectra, which have a complete overlap at 905 nm. (b) Raster plot of representative channels from multielectrode array (MEA) recordings of neurons expressing ChR2 and GCaMP3 shows that responses are abolished once GCaMP3 imaging is performed in parallel with ChR2 stimulation. (c) Combination of ChR2 stimulation with Rhod-2 calcium imaging: stimulus locked responses to 0.5 s wide-field stimulation flashes are seen both in electrical recordings raster plots (left, four representative channels) and as calcium transients (right, four other selected neurons, arrows indicate the stimulus timing). Scale bar: 10 s and . (d) Stimulation field maps superimposed onto fluorescence image of a culture seeded on an MEA (black dots are electrodes). Maps are estimated using spike-triggered averaging of pseudorandom holographic patterns (20 patches each). Scale bar: .

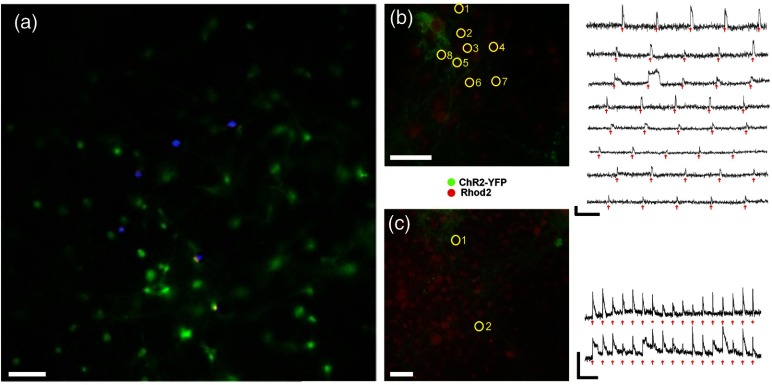

Fig. 3.

Stimulation of ChR2 expressing neurons with a 2P holographic pattern in 2-D culture. (a) Concept image of holographic stimulation: superimposed image of ChR2 expressing neurons in 2-D culture (green) with a 2P holographic stimulation pattern (blue) targeted to specific neurons (separately projected over a thin fluorescein layer and captured). (b) and (c) Multicell targeting of ChR2-expressing neurons (surrounded by yellow circles). On the right, calcium transients show stimulus locked responses to various stimulation patterns of distributed spots: (b) sequential stimulation of multiple cells in culture through 0.8 NA. Stimulation pulse duration: 50 ms. (c) Simultaneous targeting of cells through 0.5 NA. Stimulation pulse duration: 100 ms. Arrows indicate the timing of the holographic 2P stimuli. Scale bars for calcium traces: 20 s, . Scale bar for cell images: .

4. Results

4.1. Screening Calcium Indicators for Imaging Activity Patterns of ChR2 Stimulated Neurons

To find an effective combination of probes for parallel stimulation and imaging and to validate our 2P-HONS system, we applied all-optical single-photon imaging and stimulation to cortical neurons seeded on MEAs and recorded both spontaneous and stimulated activity. This experimental approach, using the (single photon) optical system previously described in Reutsky-Gefen et al.,29 enables simultaneous electrical and fluorescence-based neural activity recordings for validating the all-optical measurements. Using this system, we tested the possibility to stimulate and image cultures transfected with viral vectors carrying ChR2-mCherry and GCaMP3 in parallel (following Guo et al.10), as well as the combination of ChR2-eYFP with the organic red calcium indicator Rhod-2-AM (Invitrogen), whose single-photon excitation spectrum is well-separated from that of ChR2 [Fig. 2(a), left].

We first tested the possibility to stimulate and image cultures transfected with viral vectors carrying ChR2-mCherry and GCaMP3 in parallel. Neurons were stimulated using wide-field blue laser light flashes (1 s flash duration, 9 s OFF, , , VD-IIA DPSS laser; Sintec Optronics Technology) either with or without low intensity epifluorescent illumination for calcium imaging of GCaMP3 (, ). Robust electrical responses to the light flashes were recorded when no calcium imaging of GCaMP3 was done in parallel [Fig. 2(b), upper panel]. However, these activity responses were abolished once the epifluorescence light source was lit [Fig. 2(b), lower panel]. Excitation results for this probe combination were also not observed optically even when the GCaMP’s illumination intensity was reduced and imaged by an EMCCD camera at high gain. These results indicate that ChR2 stimulation and calcium imaging excitation wavelengths overlap prevented the use of ChR2 in combination with GCaMP3 under these experimental conditions [Fig. 2(b)].

In contrast, ChR2-eYFP transfected cultures stained with Rhod-2 presented a high signal baseline and strong calcium response signals. In order to image calcium changes with Rhod-2 while completely avoiding ChR2 activation, we used a Texas Red filter cube (570Ex/625Em, Nikon) where the excitation filter was replaced to a narrow band filter around 580 nm (HQ580/13x, Chroma) since ChR2 produces no photocurrent at wavelengths between 550 and 650 nm [Fig. 2(a)]. With this filter set, it was possible to perform both optical and electrical recording of the stimulated neural activity simultaneously without causing ChR2 desensitization [Fig. 2(c)]. Cells were illuminated with average powers of () for imaging and of () for wide-field stimulation (0.5 s ON/ 10 s OFF pulses). These stimuli caused responses to be observed on multiple electrodes [Fig. 2(c), left], as well as in the cellular calcium signals, where robust stimulus-locked calcium traces were observed [Fig. 2(c), right]. Additional study of these optogenetic responses included mapping of stimulation fields for different units by spike-triggered averaging of fast pseudorandom holographic patterns [Fig. 2(d), procedure previously described in Ref. 29]. The resulting stimulation fields were relatively large, including both cells’ somata and dendritic trees, and were clearly not disrupted by the constant illumination for Rhod-2 calcium imaging throughout the mapping experiments.

4.2. All-Optical Probing of Cultured Neural Networks

We tested the basic 2P-HONS system’s ability to stimulate cultured neurons by imaging their stimulated responses using the single-photon epifluorescence imaging subsystem. Planar neuronal networks were transfected with ChR2-eYFP and bath-loaded with the fluorescent calcium indicator Rhod-2 [Figs. 3(b) and 3(c) left, see also relevant spectra and their separation in Fig. 2(a)]. Several stimulation protocols were used: sequential stimulation of multiple neurons in the culture at a constant rate [Fig. 3(b) right, 50 ms stimulation] and simultaneous stimulation of a number of cells at a constant rate [Fig. 3(c) right, 100 ms stimulation]. Single spots were illuminated on the sample through a or objective lenses at selected locations and the power directed to each spot was on average with minimal excitation power of 9 mW. The cells were successfully excited using the 2P HONS system, causing a rise in the calcium signal following the localized excitation [Figs. 3(b) and 3(c) right].

4.3. Improving the Axial Resolution of Cell Matched Patches

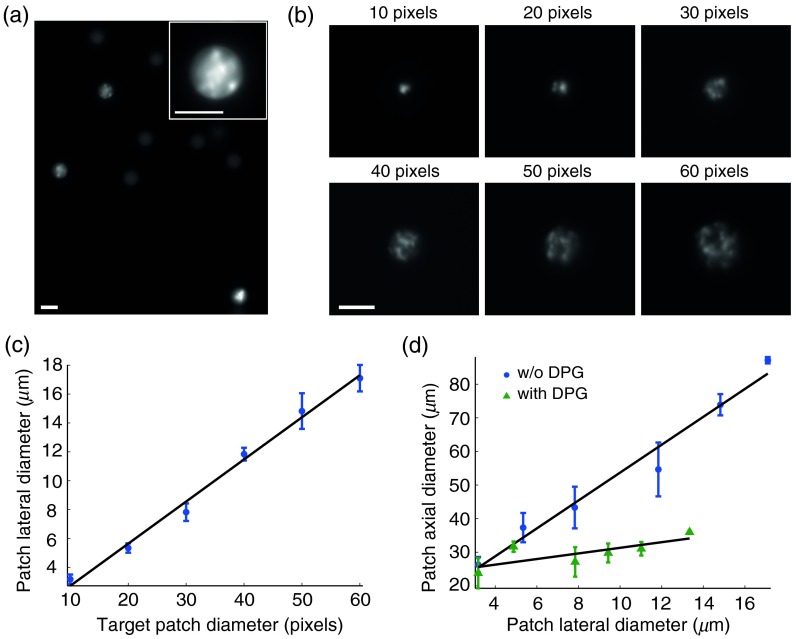

To robustly stimulate ChR2-expressing neurons, it is desirable to create illumination patches that will effectively cover the cell’s membrane4,29 and simultaneously open a larger amount of channels. This capability is demonstrated in our system by selectively projecting cell matched diameter patches onto beads [Fig. 4(a)]. Different-sized patches projected onto a fluorescein layer have the expected linear relationship between the target patch size and their lateral dimension [Figs. 4(b) and 4(c)]. These holographic patches are inherently accompanied by holographic speckle noise, and therefore we averaged over five circularly shifted holograms for each patch size to reduce the speckle noise.30,31 Increasing the patch’s diameter strongly affects its axial size, which quickly exceeds cellular dimensions—calling for TF-based improvement of the axial resolution of the light patches.

Fig. 4.

Projection of cell-size illumination patches through objective in conventional (non-TF) and TF modes. (a) Excitation patches matched to a selection of fluorescent beads in order to cover their whole cross-section. (b) Images of different sized non-TF patches projected on thin fluorescein layer and averaged over five different holograms to reduce speckle noise. (c) Correspondence between illumination patch target diameter and their corresponding lateral dimensions (shown for non-TF mode). (d) Variable-sized illumination patches and their corresponding axial dimensions for both modes. Scale bars: .

In order to generate optically sectioned holographic illumination patterns by TF, the 905-nm optimized DPG was inserted into the optical path. Consistent with previous studies,19 when TF is introduced, the strong coupling seen between the patch lateral size and its axial dimension, becomes only weakly dependent on patch size [Fig. 4(d); best fit linear slopes of 3.77 versus 0.83, respectively], providing a regime with suitably cell-matched patches in our system.

5. Discussion

This study focused on advancing the available neurophotonic toolbox toward enabling bidirectional all-optical 3-D probing of neuronal networks, by combining optical system development with the identification of a cross-talk-free probe-indicator pair. Our approach is based on pairing a hybrid multiphoton holographic stimulation system to our hybrid multiphoton microscope, where the hybrid subsystems use DPGs (grisms) to seamlessly combine conventional multiphoton excitation with TF for improved axial characteristics, when needed. We have shown that the amplified laser source and holographic system operating at 905 nm can successfully drive activity in selected ChR2-expressing neurons (ChR2 peak 2P excitation is at 880 to 920 nm4).

A major technical limitation of the current study stemmed from the unavailability of an efficient femtosecond laser amplifier and SLM to work with the 900 nm range required for stimulating and imaging state of the art genetically encoded probes. The suboptimal efficiency at this wavelength of the current laser amplifier and SLM we used (originally designed for ) led to relatively low multiphoton excitation efficiencies. As a result, only a limited implementation study is presented, where effectively testing multicellular stimulation patterns was not feasible, as well as study of patch-based TF stimulation, the effect of tissue scattering, and simultaneous multiphoton stimulation and imaging—all of which will be pursued in a future optimized setting. Nevertheless, several earlier studies have explored the effect of TF patch size increase on optogenetic excitation timing and efficiency, using 2P4,5 or single-photon excitation,29 and their results clearly suggest that constant-intensity spots5,29 with increasing illumination areas provide a stronger drive and thus increase the stimulation effectiveness and reduce its latency. Furthermore, recent work has also illustrated that TF has additional benefits in mitigating the effects of tissue scattering.18,32,33

It is important to note the potential advantage of the hybrid TF design, which was originally introduced to allow a seamless transition between two microscopic scan modes, in the context of multiphoton HONS. As aforementioned, TF provides the major benefit of axially confined excitation of spatially extended patches and the associated descattering effect32 but has the important drawback of constraining the excitation to a specific plane. Thus, in this mode, unlike regular HONS, access to a 3-D volume in TF mode requires the addition of an axial scanning mechanism—directly or remotely,8,34,35 and it is therefore advantageous that the hybrid design leaves it optional.

Among the combinations tested of a calcium imaging indicator with the optogenetic photostimulation probe ChR2, we found that pairing ChR2 with the red calcium indicator Rhod-2 provided the best option for simultaneous all-optical interfacing. In contrast to Guo et al.,10 we were unable to practically image the GCaMP3 probe without desensitizing ChR2 even at the minimal light levels required for imaging using our EMCCD camera, and consequently we were forced to give up this option [expecting 2P excitation to likely be as problematic, see Fig. 2(a)]. The source of this discrepancy is not completely clear, because Guo et al. do not provide many technical details—they imaged Caenorhabditis elegans, which do not fire action potentials and report only extended time responses; it is also possible that they were able to use effectively lower light levels with their spinning disk confocal microscope. Correspondingly, the very recent report by Szabo et al.36 coupled ChR2 and GCaMP5G in a single-photon bidirectional in vivo neural interface. Szabo et al. reported imaging illumination intensities of (at 491 nm) which are at least one order of magnitude higher than those we tested and have found to desensitize the ChR2-cortical neurons. This is putatively consistent with the extremely high stimuli required for eliciting responses (24 to 60 ms long pulses at 50 to to elicit ). This potentially suggests that the partially activated ChR2 channels may change the neuron’s baseline excitability and generally appears to support ruling out this pair’s use in a millisecond-precise all-optical interface. In general, such all-optogenetic GECI-opsin pair would be highly advantageous, because they can be introduced by a single genetic transfection and provide long-term stable interfacing. Indeed, pairing the red-shifted opsin C1V137 with GCaMP6 has led to the very recent successful demonstration by Packer et al.12 of in vivo all-optical interfacing. However, currently, red-shifted opsins like C1V137 and ReaChR38 have a long “shoulder” that overlaps with the GCaMP-family excitation spectrum, disrupting two-color pairing (this cross-talk level is evaluated by Packer et al.12). Conversely, compared to early GCaMP-family GECIs, most of the red-shifted GECI tend to have a lower baseline signal, suffer from faster photobleaching, and their normalized calcium changes are two to four times lower than GCaMP3.39 Recently, a new mApple-based red GECI, R-CaMP2, with improved performance was published.40 However, a previous mApple-based red GECI presented a confounding blue-light excited artifact which is very similar to the expected calcium response,39,41 and therefore the possible pairing of R-CaMP2 with ChR2 still needs to be studied carefully. We note that our initial tests with a ChR2-RCaMP construct, an mRuby-based GECI which does not exhibit the blue light artifact, were not promising (data not shown), but it is anticipated that newer versions of red GECIs will provide a better substitute to Rhod-2.

We anticipate that all-optical neuronal interfaces based on spectrally orthogonal genetically encoded combinations of actuators and calcium or voltage11 indicators will find diverse applications in the study and control of large neuronal populations in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number 1U01NS090498-01 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Niedersachsen-Israel (grant # VWZN2632) and the European Research Council (grant #211055). The authors thank Jason Kerr, Tony Yasniger and the late Avigdor Meir for their assistance in shifting the RegA laser’s wavelength; Noam Cohen and Shem-Tov Halevi for their advice and assistance.

Biographies

Shir Paluch-Siegler is a system engineer in the biomedical engineering industry. She led this project as part of her MSc degree in professor Shy Shoham’s laboratory. She holds BSc and MSc degrees in biomedical engineering from the Technion—Israel Institute of Technology.

Tom Mayblum is a graduate student at the neural interface engineering lab. He obtained his BSc degree in biomedical engineering from the Technion—Israel Institute of Technology. His research focuses on designing and implementing methods for functional neural activity imaging and stimulation using two-photon microscopy, temporal focusing, and holography.

Hod Dana is a research specialist at the HHMI Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Virginia, and works in the GENIE project for developing genetically encoded neuronal activity indicators. He received his BSc (cum laude) and PhD degrees in biomedical engineering from the Technion—Israel Institute of Technology, where he worked with Shy Shoham on developing experimental and analytical methods for rapid optical monitoring of large neuronal networks activity.

Inbar Brosh is a lab manager in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the Technion—Israel Institute of Technology. She works at the neural interface engineering lab (NIEL) and the biomechanics of ultrasound interaction with cell and tissue lab. She holds a BSc degree in life science and MSc and PhD degrees in medical science from Ben-Gurion University, and she was a postdoctoral fellow at Haifa University.

Inna Gefen is a faculty member at the Department of Medical Engineering at Ruppin Academic Center, where she teaches advanced courses in biomedical signal processing and development of medical instrumentation. She holds a BSc degree in biomedical engineering from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and a PhD degree in biomedical engineering from Technion—Israel Institute of Technology.

Shy Shoham is a biomedical engineering associate professor at the Technion—Israel Institute of Technology, where his lab develops photonic, acoustic, and computational tools for interfacing with retinal and brain circuits. He holds a BSc degree in physics (Tel Aviv University), a PhD degree in bioengineering (University of Utah), and was a Lewis–Thomas fellow at Princeton University. He is on the editorial boards of the Journal of Neural Engineering and Translational Vision Science and Technology.

References

- 1.Rickgauer J. P., Deisseroth K., Tank D. W., “Simultaneous cellular-resolution optical perturbation and imaging of place cell firing fields,” Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1816–1824 (2014). 10.1038/nn.3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pala A., Petersen C. C., “In vivo measurement of cell-type-specific synaptic connectivity and synaptic transmission in layer mouse barrel cortex,” Neuron 85, 68–75 (2015). 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoham S., et al. , “Rapid neurotransmitter uncaging in spatially defined patterns,” Nat. Methods 2, 837–843 (2005). 10.1038/nmeth793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrasfalvy B. K., et al. , “Two-photon single-cell optogenetic control of neuronal activity by sculpted light,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 11981–11986 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1006620107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papagiakoumou E., et al. , “Scanless two-photon excitation of channelrhodopsin-2,” Nat Methods 7, 848–854 (2010). 10.1038/nmeth.1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikolenko V., Poskanzer K. E., Yuste R., “Two-photon photostimulation and imaging of neural circuits,” Nat. Methods 4, 943–950 (2007). 10.1038/nmeth1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dal Maschio M., et al. , “Simultaneous two-photon imaging and photo-stimulation with structured light illumination,” Opt. Express 18, 18720–18731 (2010). 10.1364/OE.18.018720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anselmi F., et al. , “Three-dimensional imaging and photostimulation by remote-focusing and holographic light patterning,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 19504–19509 (2011). 10.1073/pnas.1109111108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Go M. A., et al. , “Simultaneous multi-site two-photon photostimulation in three dimensions,” J. Biophotonics 5, 745–753 (2012). 10.1002/jbio.201100101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo Z. V., Hart A. C., Ramanathan S., “Optical interrogation of neural circuits in Caenorhabditis elegans,” Nat. Methods 6, 891–896 (2009). 10.1038/nmeth.1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochbaum D. R., et al. , “All-optical electrophysiology in mammalian neurons using engineered microbial rhodopsins,” Nat. Methods 11, 825–833 (2014). 10.1038/nmeth.3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Packer A. M., et al. , “Simultaneous all-optical manipulation and recording of neural circuit activity with cellular resolution in vivo,” Nat. Methods 12, 140–146 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sjulson L., Miesenbock G., “Photocontrol of neural activity: biophysical mechanisms and performance in vivo,” Chem. Rev. 108, 1588–1602 (2008). 10.1021/cr078221b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rickgauer J. P., Tank D. W., “Two-photon excitation of channelrhodopsin-2 at saturation,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 15025–15030 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0907084106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Packer A. M., et al. , “Two-photon optogenetics of dendritic spines and neural circuits,” Nat. Methods 9, 1202–1205 (2012). 10.1038/nmeth.2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oron D., Tal E., Silberberg Y., “Scanningless depth-resolved microscopy,” Opt. Express 13, 1468–1476 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.001468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tal E., Oron D., Silberberg Y., “Improved depth resolution in video-rate line-scanning multiphoton microscopy using temporal focusing,” Opt. Lett. 30, 1686–1688 (2005). 10.1364/OL.30.001686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dana H., et al. , “Line temporal focusing characteristics in transparent and scattering media,” Opt. Express 21, 5677–5687 (2013). 10.1364/OE.21.005677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papagiakoumou E., et al. , “Patterned two-photon illumination by spatiotemporal shaping of ultrashort pulses,” Opt. Express 16, 22039–22047 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.022039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papagiakoumou E., et al. , “Temporal focusing with spatially modulated excitation,” Opt. Express 17, 5391–5401 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.005391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dana H., et al. , “Hybrid multiphoton volumetric functional imaging of large-scale bioengineered neuronal networks,” Nat. Commun. 5, 3997 (2014). 10.1038/ncomms4997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrodel T., et al. , “Brain-wide 3D imaging of neuronal activity in Caenorhabditis elegans with sculpted light,” Nat. Methods 10, 1013–1020 (2013). 10.1038/nmeth.2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittmann W., et al. , “Two-photon calcium imaging of evoked activity from L5 somatosensory neurons in vivo,” Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1089–1093 (2011). 10.1038/nn.2879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dana H., Shoham S., “Remotely scanned multiphoton temporal focusing by axial grism scanning,” Opt. Lett. 37, 2913–2915 (2012). 10.1364/OL.37.002913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zipfel W. R., Williams R. M., Webb W. W., “Nonlinear magic: multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences,” Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 1369–1377 (2003). 10.1038/nbt899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Leonardo R., Ianni F., Ruocco G., “Computer generation of optimal holograms for optical trap arrays,” Opt. Express 15, 1913–1922 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.001913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brainard D. H., “The psychophysics toolbox,” Spat. Vision 10, 433–436 (1997). 10.1163/156856897X00357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golan L., et al. , “Design and characteristics of holographic neural photo-stimulation systems,” J. Neural Eng. 6, 066004 (2009). 10.1088/1741-2560/6/6/066004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reutsky-Gefen I., et al. , “Holographic optogenetic stimulation of patterned neuronal activity for vision restoration,” Nat. Commun. 4, 1509 (2013). 10.1038/ncomms2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golan L., Shoham S., “Speckle elimination using shift-averaging in high-rate holographic projection,” Opt. Express 17, 1330–1339 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.001330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matar S., Golan L., Shoham S., “Reduction of two-photon holographic speckle using shift-averaging,” Opt. Express 19, 25891–25899 (2011). 10.1364/OE.19.025891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papagiakoumou E., et al. , “Functional patterned multiphoton excitation deep inside scattering tissue,” Nat. Photonics 7, 274–278 (2013). 10.1038/nphoton.2013.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bègue A., et al. , “Two-photon excitation in scattering media by spatiotemporally shaped beams and their application in optogenetic stimulation,” Biomed. Opt. Express 4, 2869–2879 (2013). 10.1364/BOE.4.002869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Botcherby E. J., et al. , “An optical technique for remote focusing in microscopy,” Opt. Commun. 281, 880–887 (2008). 10.1016/j.optcom.2007.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dana H., Shoham S., “Remotely scanned multiphoton temporal focusing by axial grism scanning,” Opt. Lett. 37, 2913–2915 (2012). 10.1364/OL.37.002913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szabo V., et al. , “Spatially selective holographic photoactivation and functional fluorescence imaging in freely behaving mice with a fiberscope,” Neuron 84, 1157–1169 (2014). 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yizhar O., et al. , “Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction,” Nature 477, 171–178 (2011). 10.1038/nature10360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin J. Y., et al. , “ReaChR: a red-shifted variant of channelrhodopsin enables deep transcranial optogenetic excitation,” Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1499–1508 (2013). 10.1038/nn.3502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akerboom J., et al. , “Genetically encoded calcium indicators for multicolor neural activity imaging and combination with optogenetics,” Front. Mol. Neurosci. 6(2) (2013). 10.3389/fnmol.2013.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inoue M., et al. , “Rational design of a high-affinity, fast, red calcium indicator R-CaMP2,” Nat. Methods 12, 64–70 (2015). 10.1038/nmeth.3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu J., et al. , “Improved orange and red indicators and photophysical considerations for optogenetic applications,” ACS Chem. Neurosci. 4, 963–972 (2013). 10.1021/cn400012b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]