Background: Mecp2 disruption causes hyperexcitability of locus coeruleus (LC) neurons with autonomic dysfunction.

Results: Agonists for extrasynaptic GABA receptors produced large tonic currents, lowered neuronal excitability, and alleviated breathing abnormalities in Mecp2−/Y mice.

Conclusion: Mecp2 disruption augments extrasynaptic GABAergic inhibition in locus coeruleus neurons.

Significance: These receptors may be targeted to improve neuronal excitability and breathing abnormalities in Rett syndrome.

Keywords: autism, electrophysiology, GABA receptor, pharmacology, respiration, locus coeruleus, Rett syndrome, THIP, breathing abnormalities, tonic GABAA currents

Abstract

People with Rett syndrome and mouse models show autonomic dysfunction involving the brain stem locus coeruleus (LC). Neurons in the LC of Mecp2-null mice are overly excited, likely resulting from a defect in neuronal intrinsic membrane properties and a deficiency in GABA synaptic inhibition. In addition to the synaptic GABA receptors, there is a group of GABAA receptors (GABAARs) that is located extrasynaptically and mediates tonic inhibition. Here we show evidence for augmentation of the extrasynaptic GABAARs in Mecp2-null mice. In brain slices, exposure of LC neurons to GABAAR agonists increased tonic currents that were blocked by GABAAR antagonists. With 10 μm GABA, the bicuculline-sensitive tonic currents were ∼4-fold larger in Mecp2-null LC neurons than in the WT. Single-cell PCR analysis showed that the δ subunit, the principal subunit of extrasynaptic GABAARs, was present in LC neurons. Expression levels of the δ subunit were ∼50% higher in Mecp2-null neurons than in the WT. Also increased in expression in Mecp2-null mice was another extrasynaptic GABAAR subunit, α6, by ∼4-fold. The δ subunit-selective agonists 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol hydrochloride and 4-chloro-N-[2-(2-thienyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-3-yl]]benzamide activated the tonic GABAA currents in LC neurons and reduced neuronal excitability to a greater degree in Mecp2-null mice than in the WT. Consistent with these findings, in vivo application of 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol hydrochloride alleviated breathing abnormalities of conscious Mecp2-null mice. These results suggest that extrasynaptic GABAARs seem to be augmented with Mecp2 disruption, which may be a compensatory response to the deficiency in GABAergic synaptic inhibition and allows control of neuronal excitability and breathing abnormalities.

Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT)2 is a neurodevelopmental disease with ∼0.01% morbidity rate in live-born females worldwide (1). Over 90% of RTT cases are caused by mutations of the X-linked MECP2 gene encoding methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2), a transcription regulator (1). People with RTT usually develop autism-like symptoms 6–18 months after birth, which include stereotypical repetitive hand movements, social anxiety, and seizures. Dysfunctions in the autonomic nervous system, such as breathing instability, gastrointestinal disorders, and cardiac arrhythmia, are common (2, 3).

The norepinephrine (NE) system in the brain stem is involved in autonomic function, especially NEergic neurons in the locus coeruleus (LC). Recent studies by us and other laboratories have shown that the LC neurons in Mecp2-null mice are abnormal or defective. The defect manifests itself as reduced expression of NE synthetic enzymes, hyperexcitability, and impaired CO2 chemosensitivity (4–9). The hyperexcitability of LC neurons is attributable to the intrinsic membrane properties of the cells and a decrease in synaptic inhibition mediated by GABA (4, 10). Both GABAA and GABAB receptor-mediated postsynaptic inhibition are reduced, and the GABA release from presynaptic terminals is significantly low (10). Consistent with these observations, defects in the GABAA receptor (GABAAR) system are also found in other brain regions (11–14). Selective deletion of the Mecp2 gene in GABAergic neurons recapitulates most RTT phenotypes in mice (15). These findings indicate that the GABA system plays an important role in the development of RTT.

GABA is the most prominent inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, acting on both synaptic and extrasynaptic GABARs. The synaptic GABAARs are found in postsynaptic membranes of neurons. In adult neurons, activation of the synaptic GABAARs produces fast inhibitory postsynaptic currents and hyperpolarization of the postsynaptic cells. The extrasynaptic GABAARs known as tonic receptors are characterized by their extrasynaptic location, high sensitivity to GABA, capability to produce tonic currents with long-lasting hyperpolarization, and availability for modulation by conventional GABAAR ligands as well as more selective extrasynaptic GABAAR modulators (16, 17).

Both of the synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAARs are pentamers, usually composed of two to three heteromeric subunits with a total of 19 (α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, θ, ϵ, π, and ρ1–3) (16). GABAARs with different combinations of subunits are found in different neurons. γ2-containing receptors are mainly localized at the synapse, playing a key role in GABA synaptic transmission (18, 19). The δ subunit, usually assembled with two α and two β subunits, is the major contributor of the extrasynaptic GABAARs (17, 19). These receptors are responsible for tonic GABA inhibition without interfering with synaptic transmission, which is due to their high affinity to GABA and weak desensitization.

The findings of defects in synaptic GABAAR-mediated synaptic inhibition in Mecp2-null mice are encouraging because therapeutical GABAAR activators are widely available. These drugs may be used to correct the defects in the GABA system and relieve RTT-like symptoms. Indeed, several recent studies have shown that the breathing disorders of Mecp2-null mice can be alleviated by augmenting GABA synaptic inhibition (20, 21). In contrast to the rich information of the synaptic GABAARs in RTT research (10, 11, 13, 22–25), how the extrasynaptic GABAARs are affected by Mecp2 disruption remains unknown. The capability of these extrasynaptic GABAARs to reduce neuronal excitability without interrupting synaptic transmission suggests that these receptors may allow an alternative therapeutic intervention to RTT. Therefore, we studied the extrasynaptic GABAA currents in LC neurons in the WT and mouse model of RTT.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Female heterozygous mice (genotype, Mecp2+/−; strain name, B6.129P2(C)-Mecp2tm1.1Bird/J (The Jackson Laboratory stock no. 003890) were cross-bred with WT males to produce RTT model mice with the genotype Mecp2−/Y. The PCR protocol from The Jackson Laboratory was used to identify the genotype. Only Mecp2−/Y male mice aged 3 weeks were used in the experiments, and their littermates with the genotype Mecp2+/Y were used as a control. All experimental procedures in mice were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Georgia State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Brain Slice Preparation

Brain slices were prepared as described previously (4, 26). In brief, a mouse was decapitated after deep anesthesia with inhalation of saturated isoflurane. The brain stem was obtained and immediately placed into ice-cold sucrose-rich artificial CSF (aCSF) containing 220 mm sucrose, 1.9 mm KCl, 0.5 mm CaCl2, 6 mm MgCl2, 33 mm NaHCO3, 1.2 mm NaH2PO4, and 10 mm d-glucose. The solution was bubbled with 95% O2 balanced with 5% CO2 (pH 7. 40). Transverse pontine sections (250–300 μm) containing the LC area were obtained using a vibratome sectioning system and then recovered at 33 °C for 30 min in normal aCSF containing 124 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 26 mm NaHCO3, 1.3 mm NaH2PO4, and 10 mm d-glucose. The brain slices were kept at room temperature before use. At recording, the slices were perfused with oxygenated aCSF at a rate of 2 ml/min and maintained at 34–35 °C in a recording chamber.

Electrophysiology

LC neurons were identified as described previously (22). Whole-cell voltage clamping and whole-cell current clamping were performed with patch pipettes. A pipette puller (model P-97, Sutter, Novato, CA) was used to pull the patch pipettes with a resistance of 3–5 MΩ. Only neurons with a membrane potential of less than −40 mV and an action potential of more than 65 mV were accepted for further experiments. In voltage clamping, the pipettes were filled with solution containing 50 mm KCl, 85 mm CsCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm magnesium-ATP, 1 mm sodium-GTP, 10 mm HEPES, and 0.5 mm EGTA (pH 7.30). The brain slice were perfused with oxygenated aCSF containing 130 mm NaCl, 3.5 mm KCl, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 1.5 mm MgSO4, 10 mm d-glucose, 24 mm NaHCO3, and 2 mm CaCl2 (pH 7.40). GABAAR-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) and tonic currents were isolated with the following agents in bath solution: 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (10 μm, Tocris, Minneapolis, MN, disodium salt), an AMPA receptor antagonist; DL-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (10 μm, Tocris, sodium salt), an NMDA receptor antagonist; and strychnine (1 μm, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), a glycine receptor antagonist. All recordings were performed at a holding potential of −70 mV. 4,5,6,7-Tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol hydrochloride (THIP, also known as gaboxadol, Tocris, hydrochloride), 4-chloro-N-[2-(2-thienyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-3-yl]]benzamide (DS2, Tocris), bicuculline (Tocris), and picrotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used to measure the tonic current. In current clamping, the pipette solution contained 130 mm potassium gluconate, 10 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 2 mm magnesium-ATP, 0.3 mm sodium-GTP, and 0.4 mm EGTA (pH 7. 3). The bath solution was normal aCSF bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7. 40). The current-voltage relationship was recorded by injecting a series of step currents, typically starting from −0.16 nA, with an step increment of 0.016 nA. Recorded signals were amplified with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA), digitized at 10 kHz, filtered at 1 kHz, and collected with Clampex 8.2 data acquisition software (Molecular Devices). The temperature was maintained at 33 °C during recording by a dual automatic temperature control (Warner Instruments, New Haven, CT).

Quantitative PCR

Brain slices were obtained from 3- to 4-week-old mice. Transcripts were obtained from micropunches (∼1.5 mm in diameter) from the LC area, and cDNAs were synthesized with the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies). PCR primers for GAPDH (forward, CCAGCCTCGTCCCGTAGA; reverse, TGCCGTGAGTGGAGTCATACTG), δ subunit (forward, GGCTTCTTGGGCTTTACC; reverse, CACCCCCACTGTTTTTCTC), α4 subunit (forward, GTGGGAAATCACTCCAGCAAG; reverse, AATGCAGGGCGAGTGGAAG), α5 subunit (forward, CAAAAGAGCAGCCTCCAG; reverse, GAAAGTGCCAAACAAGATGG), α6 subunit (forward, GACTTTGCCCATCGTTCC; reverse, TGCAAAAGCTACTGGGAAGAG), β1 subunit (forward, TGGTTTTCGATCTTGTGTGTCAG; reverse, AGCCACCTCTCTCTTTGTGTTTG), β2 subunit (forward, TTCCCACTGCTGTTTCTCACATAC; reverse, ATCCTAACCACTTCTCCTTTTTTCC), and β3 subunit (forward, GTTGAGTGGTTGTGTTGCCAATG; reverse: ATGTCCCCGTGTTGGCATC) were designed with Primer Express software and synthesized from Sigma Genesis (Sigma-Aldrich). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies), following the instructions of the manufacturer, in a fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems 7500) for 40 cycles. GAPDH was used as the internal control for the quantification of subunit expression.

Single-cell PCR

Transcripts were obtained from single neurons that were studied in whole-cell recording, with which cDNAs were synthesized as described above. Three microliters of reverse transcription product were used to perform PCR with TaqDNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) for 35 cycles following the instructions of the manufacturer. Three microliters of the PCR reaction were performed with the same PCR cycling protocol as before. The second PCR reaction product was run on 2% agarose gels and was then imaged using an AlphaImager 3400 multi-function gel imager (Alpha Innotech, Santa Clara, CA). GAPDH was used as the positive control, and green fluorescent protein was used as the negative control.

Western Blot Analysis

Pontine slices (300 μm thick) containing the LC area were obtained from 3- to 4-week-old mice with a vibratome sectioning system, and the pons was processed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1% protease inhibitor. BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce) was used to estimate the protein concentrations, and 30 μg of proteins was used to detect δ subunit signals in 10% SDS-PAGE gels and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were then blocked for 2 h in 5% nonfat milk and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit GAPDH primary antibody (1:10,000, Sigma-Aldrich) and rabbit δ subunit primary antibody (1:1000, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) (27). After washing in PBS Tween, the membranes were incubated by HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10,000, Life Technologies) for 1 h at room temperature. The chemiluminescent detection system (Pierce) was used to expose the membrane to films (Hy Blot CL, Denville, Metuchen, NJ), and the photographs were scanned. The immunoblotting signals were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The δ subunit signals were normalized to the internal GAPDH controls.

Plethysmograph Recording

Mecp2-null mice 25–33 days of age were randomly separated into two groups (five mice in each group). One group of mice was injected with drug (10 mg/kg intraperitoneally), and the other group was injected with saline as a control. The breathing activities of unanesthetized mice were recorded by the plethysmograph system with an ∼40-ml plethysmograph chamber and a connected reference chamber. The individual animal was kept in the plethysmograph chamber with airflow at a rate of 60 ml/min for at least 20 min for adaptation, followed by a 20-min recording. The breathing activities were recorded continuously with a signal transducer as the barometrical changes between the plethysmograph chamber and the reference chamber. The signal was amplified and collected with Pclamp 9 software. The data analysis was done blinded to the treatment. Apnea was considered only when the breathing cycle lasted twice or longer than the previous cycle. Breathing frequency variation was calculated as the division of standard deviation of the frequency by their arithmetic mean. All standard deviations and arithmetic means were measured from three to four stretches of recordings with at least 50 breaths in each.

Data Analysis

The electrophysiological data and the plethysmograph data were analyzed with Clampfit 10.3 software. The sample sizes in all the experiments were examined with G-Power Analysis (28) to yield sufficient statistical power. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. Two-tailed Student's t test, one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test were used to perform the statistical analyses. The difference was considered significant when p ≤ 0.05.

Results

GABAAergic Tonic Currents in WT Neurons

To determine the GABAA tonic currents in LC neurons, whole-cell voltage clamping was performed in brain slices of WT mice. Inward Cl− currents were studied, with 135 mm Cl− in both the pipette and bath solutions at a holding potential of −70 mV, and glutamatergic and glycinergic currents were blocked (see “Experimental Procedures”). Under these conditions, the LC neurons showed spontaneous GABAergic IPSCs that were blocked by bicuculline (50 μm) or picrotoxin (20 μm). Meanwhile, we found that these GABAAR blockers also suppressed tonic inward currents. Therefore, we studied the GABAAergic tonic currents. The current amplitude histograms were generated under stable conditions before and after GABAAR blockade and were then fit with Gaussian distribution. The opening of the ionotropic receptors also increases the current noise levels, which were measured as the standard variation of the Gaussian distribution. We analyzed the ratio of noise levels before versus after a treatment with GABAAR blockers.

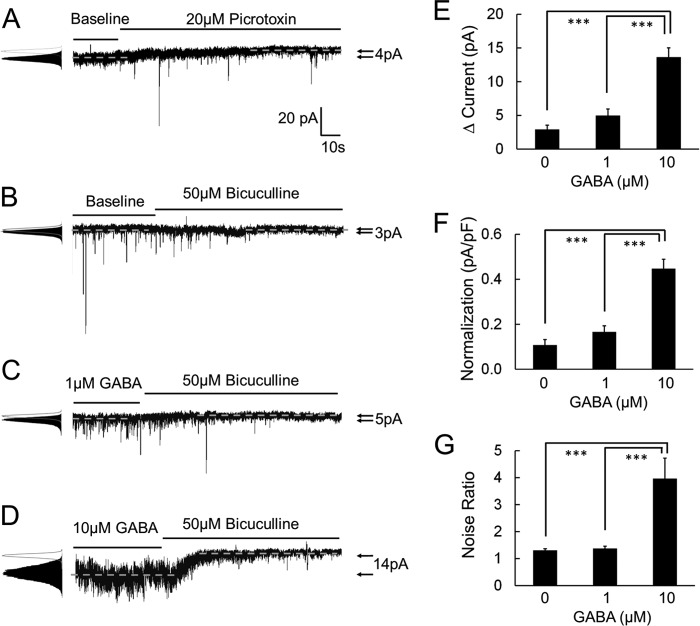

Bicuculline reduced the tonic currents by 2.9 ± 0.6 pA (n = 5), and the noise ratio was 1.31 ± 0.06 (n = 5) (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained with picrotoxin (Fig. 1A). The effects of bicuculline on the tonic currents and the noise ratio were more obvious in the presence of GABA in the perfusion solution. A pretreatment with 1 μm GABA augmented the tonic currents to 5.0 ± 1.0 pA and the noise ratio to 1.37 ± 0.08 (n = 5) (Fig. 1C). With 10 μm GABA, the tonic currents were raised to 13.6 ± 1.4 pA (n = 6) and the noise ratio to 3.97 ± 0.76 (n = 6) (Fig. 1D). The bicuculline-sensitive tonic currents and noise augmentation increased dose-dependently with increased GABA concentrations (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 1, E–G).

FIGURE 1.

GABAAR antagonists reduce the tonic currents of LC neurons in WT mice. Tonic GABAA currents were recorded by whole-cell voltage clamping with ion substitution and selective receptor blockers. A and B, in the absence of exogenous GABA in the bath solution (baseline), tonic currents were measured as the difference before and after treatment of GABAARs antagonists. Picrotoxin (20 μm) and bicuculline (50 μm) reduced both the synaptic GABAA currents (IPSCs) and the tonic GABAA currents of LC neurons in WT mice. Noise was measured as standard deviation of the currents and is shown as a ratio with versus without GABAARs antagonist treatment. The noise level was reduced with the treatment of these two GABAARs antagonists. C and D, pre-treatments with 1 μm and 10 μm GABA boost larger bicuculline-sensitive tonic current in WT LC neurons. E–G, the effects of bicuculline on tonic currents and the noise ratio increased dose-dependently with an increase in GABA concentrations. pF, picofarad. ***, p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA.

Enhancement of GABAAergic Tonic Currents in Mecp2-null Mice

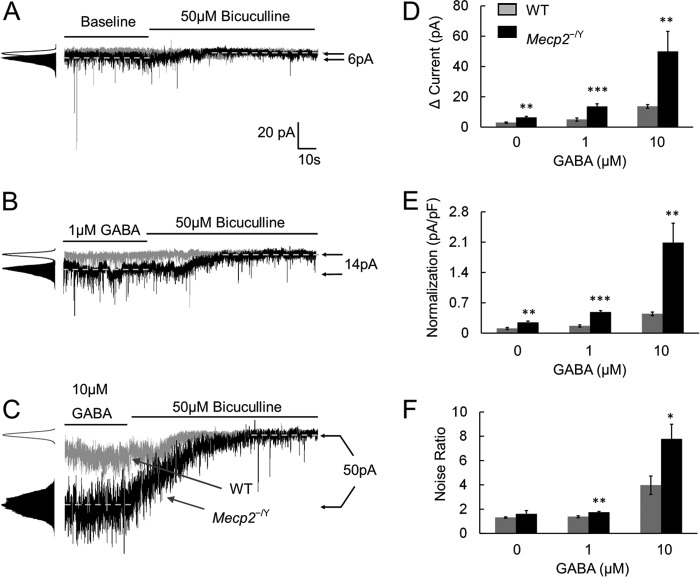

At baseline, the bicuculline-sensitive tonic currents were significantly larger in Mecp2-null mice than in WT mice (6.4 ± 0.8 pA, n = 5 versus 2.9 ± 0.6 pA, n = 5; p < 0.01, Student's t test; Fig. 2, A, D, and E). These tonic currents in Mecp2-null mice became even greater in the presence of 1 or 10 μm GABA, which were 13.5 ± 1.7 pA (n = 5) and 49.8 ± 10.7 pA (n = 6) respectively. Both were significantly higher than in the WT neurons (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, Student's t test; Fig. 2, B–E). In Mecp2-null mice, the noise ratio also increased dose-dependently with these GABA concentrations (1.74 ± 0.08 and 7.77 ± 1.21, respectively; p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively; Student's t test; Fig. 2F), although a significant difference was not found at baseline. These results suggest that bicuculline-sensitive tonic currents are significantly increased in Mecp2-null LC neurons.

FIGURE 2.

Bicuculline-sensitive tonic currents are increased in Mecp2−/Y mice. A, in comparison with WT mice, bicuculline (50 μm) reduced more tonic currents and noise in Mecp2-null mice in the absence of exogenous GABA (baseline). B and C, in the presence of 1 μm or 10 μm GABA, the bicuculline effects on the tonic currents and noise ratio were significantly larger in Mecp2-null neurons than in the WT. D–F, both tonic currents and the noise ratio increased dose-dependently with an increase in GABA concentrations. Such effects were more obvious in Mecp2-null mice. pF, picofarad. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; Student's t test.

Effects of Specific Agonists for Extrasynaptic GABAARs

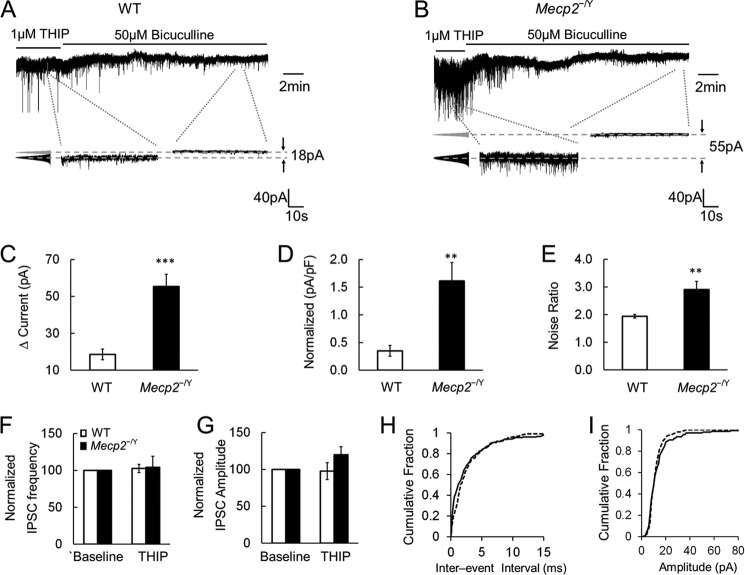

The GABAAergic tonic currents are likely to be mediated by extrasynaptic GABAARs expressed in LC neurons. Because the molecular compositions of extrasynaptic GABAARs are different from those of synaptic GABAARs, these extrasynaptic receptors can be activated with selective agonists, such as THIP and DS2, that do not affect the synaptic GABAARs (29, 30). In the presence of 1 μm THIP in the bath solution, the GABAAergic tonic currents (18.6 ± 2.9 pA, n = 5) and noise ratio (1.94 ± 0.07, n = 5) were both augmented in WT neurons (Fig. 3A). In Mecp2-null neurons, the same concentration of THIP raised the tonic currents (55.3 ± 6.6 pA, n = 5) and the noise ratio (2.91 ± 0.29, n = 5) to significantly greater degrees than in the WT neurons (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively, Student's t test; Fig. 3, B–E). THIP did not affect the frequency and amplitude of the GABAergic IPSCs in both WT and Mecp2-null LC neurons (Student's t test; Fig. 3, F–I).

FIGURE 3.

THIP boosts larger tonic currents in Mecp2−/Y mice. A–E, THIP (1 μm) applied to the bath solution triggered bicuculline-sensitive tonic currents, measuring 18.6 ± 2.9 pA, and noise ratio, measuring 1.94 ± 0.07, in WT neurons. In Mecp2-null neurons, THIP-activated tonic currents were augmented 3-fold compared with WT cells, and the noise ratio was also increased significantly. pF, picofarad. F and G, the effects of THIP on IPSC frequency and amplitude were not significantly different between WT and Mecp2-null LC neurons. H and I, analysis of the cumulative fraction of IPSCs showed that 1 μm THIP treatment did not alter the interevent interval and amplitude of GABAergic IPSCs in WT neurons. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; Student's t test.

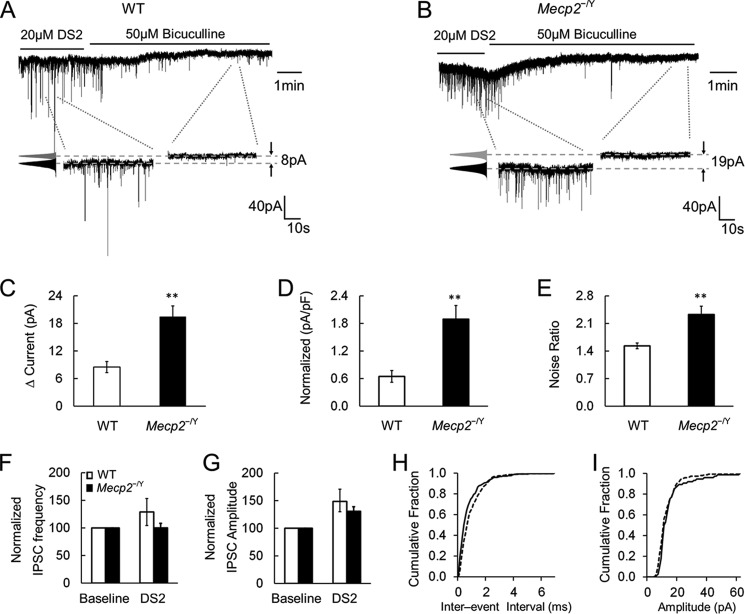

Similarly, application of DS2 (20 μm), a positive allosteric modulator of extrasynaptic GABAARs, augmented the tonic currents and noise ratio. This effect was larger in Mecp2-null mice (19.5 ± 2.3 pA, 2.32 ± 0.21, respectively; n = 5) than in WT mice (8.5 ± 1.2 pA, 1.53 ± 0.07, respectively; n = 5; p < 0.01 and p < 0.01, respectively, Student's t test; Fig. 4, A–E). Unlike THIP, DS2 augmented the frequency and amplitude of the GABAergic IPSCs in LC neurons, which may be attributed to their affinity for αβ-type GABAARs. Despite this, we did not find significant differences between WT and Mecp2-null mice (Student's t test; Fig. 4, F–I). These results indicate that the extrasynaptic GABAARs existing in LC neurons seem to have a greater effect on LC neuronal activity in Mecp2-null mice.

FIGURE 4.

DS2 raises tonic currents in Mecp2−/Y mice. A–E, application of DS2 (20 μm) enhanced tonic currents ∼3-fold and raised the noise ratio to a significantly greater degree in Mecp2-null neurons compared with the WT. pF, picofarad. F and G, the effects of DS2 on IPSC frequency and amplitude were not significantly different between WT and Mecp2-null LC neurons. H and I, cumulative analysis of IPSCs showed that DS2 shifted the interevent interval to the higher frequency range without altering the amplitude of IPSCs in WT LC neurons. **, p < 0.01; Student's t test.

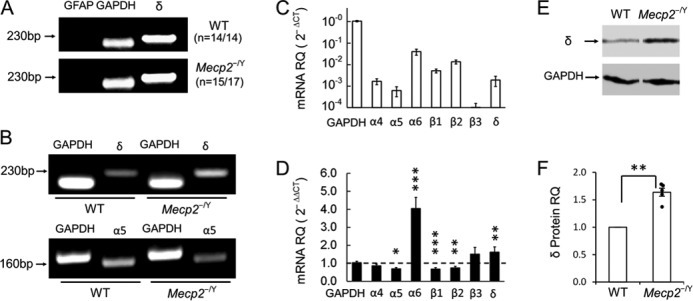

Differential Expression of GABAAR Subunits in WT and Mecp2-null Mice

The δ subunit is the principal component of extrasynaptic GABAARs, and is localized exclusively outside of the synaptic cleft, mediating GABAAergic tonic currents (5, 45). If Mecp2-null LC neurons have more extrasynaptic GABAARs, then the δ subunit should be expressed in these cells at a higher level than in WT neurons. To test this possibility, we studied δ subunit expression at the mRNA and protein levels. Single-cell PCR analysis showed that the δ subunit was expressed in most LC neurons in both WT and Mecp2-null mice (14 of 14 WT neurons and 15 of 17 Mecp2-null cells, Fig. 5A), consistent with the presence of GABAAergic tonic currents in LC neurons.

FIGURE 5.

GABAA-R subunit expression in the LC region. A, single-cell PCR showed that δ subunit, the essential subunit for extrasynaptic GABAA-Rs, was found in most LC neurons with negative GFAP and positive GAPDH expression in both groups of mice. B, RT-PCR showed expression of δ and α5 subunits. C, qPCR analysis with 2−ΔCt indicated high relative quantity (RQ) of α6, β1, β2, and δ subunits in WT mice. D, in comparison with WT levels in the 2−ΔΔCt measure, the δ subunit level was significantly increased, and α5 subunit level was reduced in Mecp2-null mice. Transcript level of the α6 subunit was also significantly higher in Mecp2-null mice. Note that the seeming increase in β3 expression was insignificant as the expression ratio was based on barely detectable WT β3 in C (means ± SE; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). E and F, Western analysis showed a significant increase of δ subunit protein expression in Mecp2-null mice.

In qPCR, the δ subunit was found to be expressed in WT LC neurons with the 2−ΔCt method (41). With the 2−ΔΔCt method (41), the expression level of the δ subunit increased 1.8- ± 0.5-fold in LC tissue micropunches obtained from Mecp2-null mice in comparison with the WT (n = 9, p < 0.01, Student's t test; Fig. 5, B–D). Western blot analysis showed that δ subunit protein expression was increased 1.6- ± 0.1-fold in Mecp2-null mice over the WT (n = 6, p < 0.01; Student's t test, Fig. 5, E and F). These results suggest that the δ subunit is expressed in LC neurons and that its increased expression in Mecp2-null mice may contribute to the abundant tonic GABAA currents.

The α5 subunit is another important contributor to extrasynaptic GABAARs (24). In single-cell PCR, the α5 transcript was barely detected in LC neurons (0 of 14 in WT and 2 of 17 in Mecp2-null mice). qPCR analysis showed that α5 expression in LC neurons was only about one-third that of δ subunit expression in WT mice. There was a significant reduction of α5 expression in Mecp2-null mice (n = 5, p < 0.05, Student's t test; Fig. 5, B–D), suggesting that the large tonic currents in Mecp2-null mice were unlikely to be produced by increased α5 expression.

The δ-containing extrasynaptic GABAARs are usually composed of one δ, two α, and two β subunits. Previous studies have reported that all three β subunits (β 1–3) and α4 and α6 subunits contribute to the assembly of extrasynaptic GABAARs (17, 31, 32). In qPCR, α6 expression was increased ∼4-fold in Mecp2-null mice over WT levels, whereas α5 expression was reduced (n = 4, p < 0.05, Student's t test; Fig. 5D). Transcript levels of β1 and β2 subunits were both reduced (n = 5, p < 0.001 and 0.01, respectively, Student's t test), whereas the β3 transcript did not change (Fig. 5D).

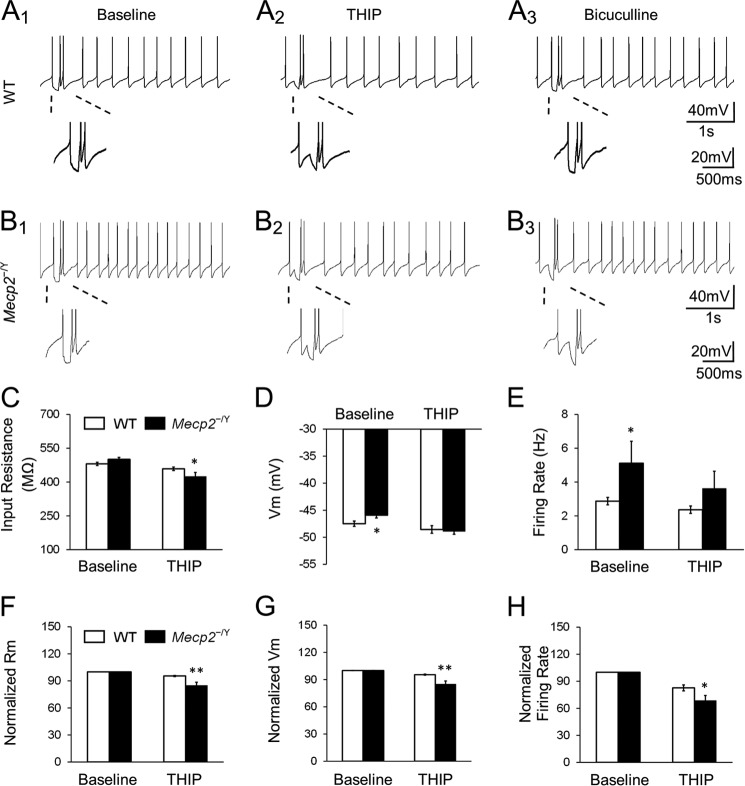

Modulation of LC Neuronal Firing Activity by Extrasynaptic GABAAR Agonists

LC neuronal electrophysiological activity was studied with current clamping. In WT mice, THIP reduced the input resistance from 480.5 ± 7.1 mΩ to 458.7 ± 7.6 mΩ. Meanwhile, THIP hyperpolarized the cells by 1.1 ± 0.4 mV and decreased the firing rate by 17.3 ± 3.3% (n = 14, Fig. 6A and C–E). In Mecp2-null mice, the same THIP treatment reduced the input resistance from 500.5 ± 8.7 mΩ to 424.9 ± 17.7 mΩ, hyperpolarized the cells by 3.0 ± 0.5 mV, and lowered the firing rate from 5.1 ± 1.3 Hz to 3.6 ± 1.6 Hz (n = 9; p < 0.05, p < 0.05 and p < 0.05, respectively, Student's t test; Fig. 6, B–E), which is approximate to the baseline level in WT LC neurons (2.9 ± 0.2 Hz in WT baseline, n = 14, Fig. 6E). All of these percentile changes were significantly greater than in the WT neurons (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, and p < 0.05, respectively; Student's t test; Fig. 6, F–H).

FIGURE 6.

THIP inhibits the LC firing activity by activating extrasynaptic GABAARs. A1–A3, application of 1 μm THIP suppressed the spontaneous firing activity with a hyperpolarization and a decrease in input resistance (Rm) of LC neurons in WT mice. The effects were abolished in the presence of bicuculline. Magnified inset with hyperpolarizing current injection indicates the input resistance. B1–B3, LC neurons in Mecp2-null mice showed the similar response to 1 μm THIP. C–E, membrane potential and firing rate showed significant differences at the baseline (normal aCSF without exogenous GABA) between WT and Mecp2-null neurons, and THIP abolished the differences. THIP treatment also produced a significant decrease in input resistance. F–H, in comparison to the WT, THIP had significantly larger effects on input resistance, membrane potential, and firing rate in Mecp2-null neurons (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; Student's t test).

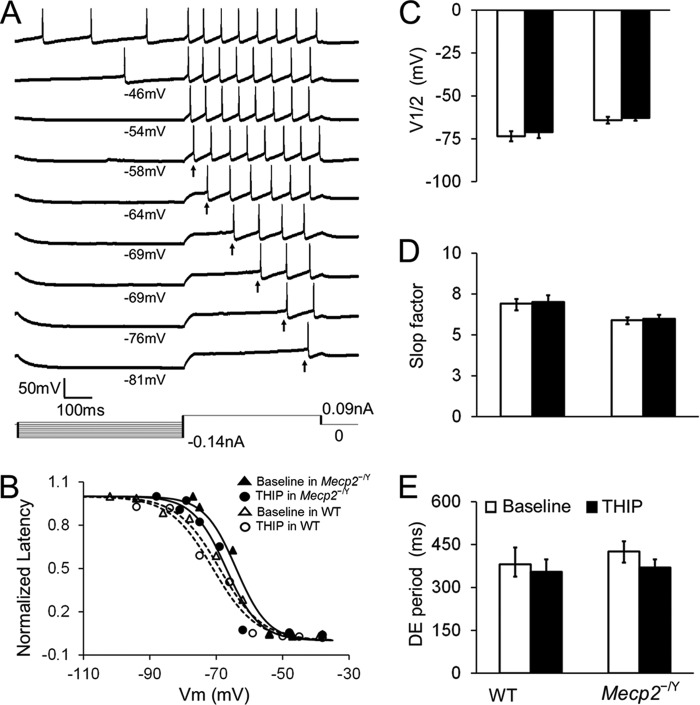

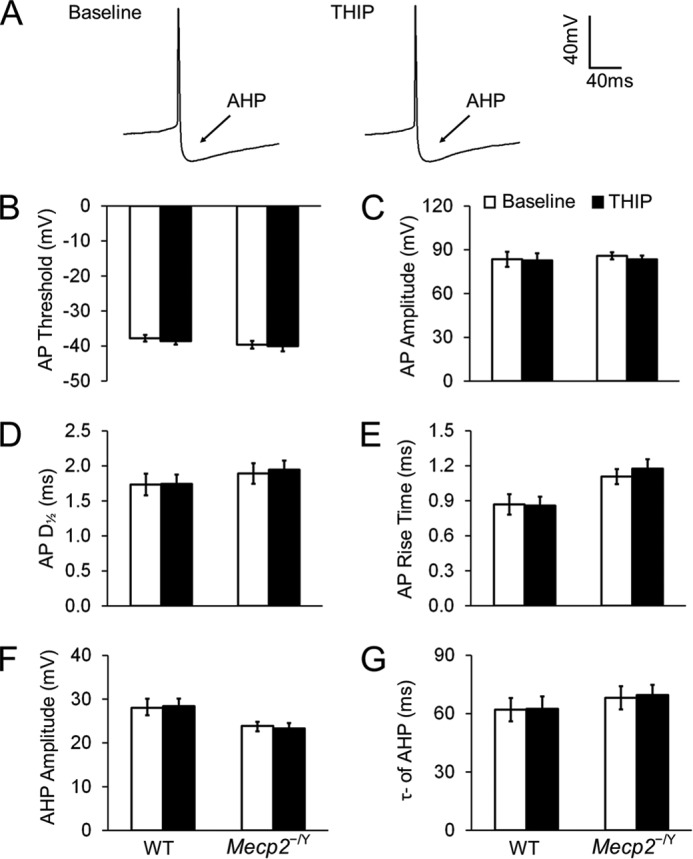

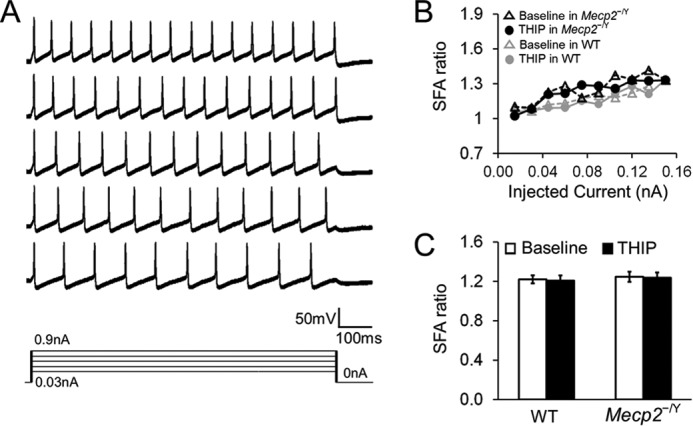

In either WT or Mecp2-null mice, 1 μm THIP did not affect the superthreshold and repetitive firing properties, including action potential morphology, after hyperpolarization (Fig. 7), spike frequency adaptation (Fig. 8), and delayed excitation (Fig. 9), when synaptic transmission was deliberately blocked. Post-inhibitory rebound and bursting activity were not found in LC neurons before and after THIP treatment in WT mice or Mecp2-null mice. Taken together, these results indicate that activation of δ subunit-containing GABAARs leads to an inhibition of LC neurons, an effect that is greater in Mecp2-null mice than in the WT, which brings the neuronal firing from hyperexcitable status to the level of WT neurons.

FIGURE 7.

THIP does not affect the morphology of action potential (AP) and afterhyperpolarization (AHP) in either WT or Mecp2-null neurons. A, spontaneous APs recorded from an LC neuron. No obvious changes in AP morphology were found after exposure to THIP. B–E, in the presence of ionotropic receptor blockers (AP5, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, and strychnine) in the bath solution, THIP did not change the AP threshold (the potential at the AP initiation point), AP amplitude (the amplitude from threshold to peak), rise time, and half-width (D½, measured at 50% amplitude) of APs in either WT or Mecp2-null neurons (n = 7 and 12; p > 0.05 and p > 0.05, respectively; Student's t test). F and G, in the presence of ionotropic receptor blockers, AHP was also not affected by THIP in WT and Mecp2-null neurons. AHP amplitude was measured from the AP threshold to the lowest hyperpolarization point, and the time constant of AHP was described with a single exponential in the period from 10% to 90% of the AHP amplitude (n = 7 and 12; p > 0.05 and p > 0.05, respectively; Student's t test).

FIGURE 8.

THIP does not affect the spike frequency adaptation (SFA) in either WT or Mecp2-null neurons. A, the SFA was studied with series of depolarizing currents (0–0.15 nA). The firing rate of the neurons declined with a long period of depolarization. B, the SFA ratio was obtained by division of the peak frequency, measured between the first two APs, by the steady-state frequency, measured between the last two APs with the same current injection. The SFA ratio was increased with the increasing depolarizing currents. THIP treatment did not affect the SFA ratio in WT and Mecp2-null neurons. C, with a 0.06-nA current injection, THIP did not affected the SFA ratio in WT nor Mecp2-null neurons (n = 6 and 9; p > 0.05 and p > 0.05, respectively; Student's t test).

FIGURE 9.

THIP does not affect delayed excitation (DE) in both WT and Mecp2-null neurons. A, DE was measured as the time delay between the starting point of the depolarization pulse and initiation of the first action potential after a prior hyperpolarization. B, DE was described as the function of the conditioning hyperpolarization, which was fit with a Boltzmann equation as D = Dmax /{1 + exp[(V − V½) / k]}, where Dmax is the maximum DE period, V is the hyperpolarizing membrane potential, V½ is the half-inactivation, and k is the Boltzmann constant or slop factor. C—E, neither WT nor Mecp2-null neurons showed a significant difference on V½, slop factor, or DE period before and after THIP treatment (n = 8 and 7; p > 0.05 and p > 0.05, respectively; Student's t test).

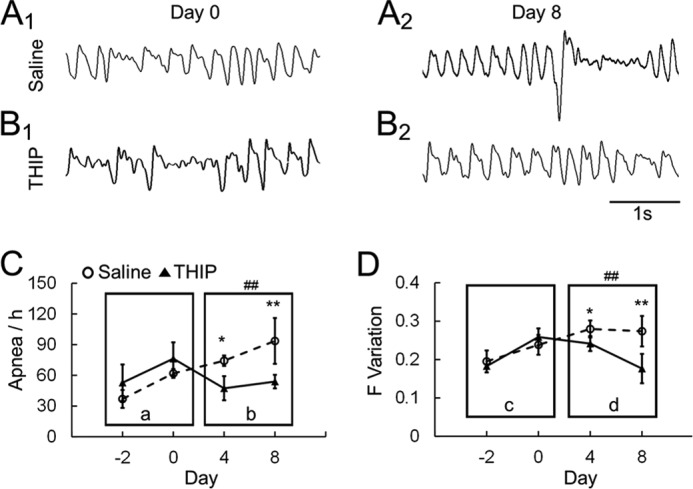

The Extrasynaptic GABAAR Agonist Improved Breathing Abnormalities

Previous studies have indicated that LC neurons are sensitive to high CO2 and low pH and that they play an important role in regulating breathing (9). In Mecp2-null mice, several groups of neurons, including LC neurons, are hyperexcitable (4, 20, 23, 33), which appears to contribute to the breathing disorders in Mecp2-null mice. To test whether activation of the extrasynaptic GABAARs can alleviate the breathing abnormalities, we studied breathing activity using plethysmography in conscious Mecp2-null mice. The mice were divided into two groups, with one receiving THIP injections (10 mg/kg intraperitoneally) and the other receiving a saline injection. At 3 weeks of age, Mecp2-null mice started to develop breathing disorders with obvious breathing frequency variation and frequent apneas. Therefore, we monitored the breathing activity of Mecp2-mull mice with THIP/saline injection once a day for 7 consecutive days starting at 26 days of age. After the 7-day treatment, Mecp2-null mice with the saline injection continued to develop severe breathing disorders with 89 ± 16 apneas/hour, an ∼50% increase compared with day 0 (n = 5, Fig. 10, A and C), and 0.29 ± 0.03 breathing frequency variation, an ∼20% increase (n = 5; Fig. 10, A and D). THIP treatment markedly reduced breathing disorders to 46 ± 6 apneas/hour, an 18% reduction compared with day 0 (n = 5; Fig. 10, B and C), and 0.17 ± 0.04 breathing frequency variation, a 32% reduction (n = 5; Fig. 10, B and D). Both breathing parameters improved significantly in the THIP group over their saline counterparts (Fig. 10, C and D; two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test). Therefore, the results suggest that the extrasynaptic GABAAR agonist THIP alleviates the breathing disorders of Mecp2-null mice.

FIGURE 10.

THIP alleviates the breathing abnormalities in Mecp2−/Y mice. A and B, Mecp2-null mice were injected with THIP (10 mg/kg intraperitoneally) or saline for 7 consecutive days. Breathing activity was recorded in a plethysmograph system 2 days before the injection. The injection started on day 0, when mice were 26 days old. All the animals developed breathing disorders before the THIP injection, showing apnea and clear breathing frequency (F) variation on day 0. On day 8, both were alleviated after THIP treatment for 7 days by showing less apnea and smaller breathing frequency variation. C and D, when apnea occurrence (events per hour, C) and breathing frequency variation (S.D./mean, D) were compared between the THIP- and saline-injected groups, THIP significantly improved both apnea and breathing frequency variation in Mecp2-null mice. Ca and Dc, there was no significant difference in the main effect, nor a significant interaction. Cb and Dd, there was a significant difference in the main effect (##, p < 0.01; two-way ANOVA) of drug treatment. No significant effect of age and no significant age-drug interaction were found. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; Tukey's post hoc test.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of extrasynaptic GABAA currents in the mouse model of RTT. Our results have shown that tonic GABAA currents in LC neurons are significantly larger in Mecp2-null neurons than in the WT, likely because of the overexpression of the GABAAR species containing δ and α6 subunits. Furthermore, activation of the extrasynaptic GABAARs appears to reduce neuronal excitability and alleviate breathing abnormalities of Mecp2-null mice.

Decreased Activity in Synaptic GABAARs in Mecp2-null Mice

Previous studies have shown that the GABAA system decreases activity in Mecp2-null mice and people with RTT. In mice, this is associated with multiple RTT-like phenotypes, including progressive motor dysfunction and abnormal breathing (15). In GABAergic neurons, impaired GABA synthesis and the consequent reduction in GABA quantum release have been found (10, 15, 25). In postsynaptic cells, there is a marked reduction in GABAAR density in the brain of RTT patients and Mecp2-null mice (34, 35). An epigenetic study in a mouse model of RTT indicates that GABAAR β3 subunit expression is reduced in the cerebellum, and another molecular study confirmed down-regulation of the β3 subunit in the cerebellum (12, 36). The α1 subunit in the frontal cortex and the α2 and α4 subunits in the ventrolateral medulla were also reduced in Mecp2-null mice (25). In LC neurons, our previous studies have shown that the postsynaptic GABAA and GABAB currents are both defective in Mecp2-null mice (10). Consistent with these findings, the therapeutic GABAAR activators diazepines and the reuptake blocker NO-711 improve RTT symptoms in animal models, including breathing (20, 21). However, it is still unclear how the extrasynaptic GABAARs are affected in Mecp2-null mice, which makes this study remarkable.

Presence of Extrasynaptic GABAARs in LC Neurons

Extrasynaptic GABAARs were first described in cerebellar cortical gray matter (37) and found later in many other brain areas, such as the cerebral cortex, dentate gyrus granule, thalamus, and neocortex (38–43). Extrasynaptic GABAARs are sensitive to low levels of ambient GABA with little desensitization. They are likely key targets for neurosteroids and alcohol (44–47) and useful targets for the treatment of some neuronal diseases, such as sleep disorders, epilepsy, stroke, and Parkinson disease (48, 49). The δ subunit is the primary component of extrasynaptic GABAARs, found exclusively in extrasynaptic locations meditating tonic inhibition (17, 19). Some other GABAAR subtypes may be also involved in extrasynaptic GABAARs, such as α5-subunit containing receptors (50–52). The results from this study suggest that extrasynaptic GABAARs are also present in LC neurons. Activation of these receptors results in tonic hyperpolarizing currents that are sensitive to GABA and the GABAAR blockers bicuculline and picrotoxin. Consistent with these electrophysiological studies, our molecular biological evidence indicates that the δ subunit is expressed in LC neurons.

Accompanying the δ subunit are two α and three β subunit species forming pentameric extrasynaptic GABAARs. Our qPCR results suggest that α6-containing extrasynaptic GABAARs seem to play a major role in Mecp2-null LC neurons, similar to mature cerebellar granule cells (53). The β1–3 subunits are necessary components in both extrasynaptic and synaptic GABAARs. Previous studies have reported an ∼30% reduction in postsynaptic GABAergic IPSCs in Mecp2-null LC neurons. The reduced α4 level found in this study is therefore consistent with the deficiency in synaptic GABAARs. Regarding the increase in α6 transcript level, it is possible that deletion of Mecp2 leads to reorganization of the GABA receptor species in LC neurons by increasing α6 subunit expression and reducing the expression of other α subunits. A similar reorganization has been found in nicotinic ACh receptors in Mecp2-null LC neurons (54). The increased α6 subunits may assemble the extrasynaptic receptors together with the δ subunit as well as synaptic GABAARs with β and γ subunits. Because all β subunits contribute to synaptic GABAARs and because synaptic GABAARs are lowered with Mecp2 knockout, it is possible that their overall reduction masks the potential up-regulation of some subunits in the extrasynaptic location. Another possibility is that the extrasynaptic GABAARs in Mecp2-null mice might be composed of more than two α subunits, which may explain the reduced expression of β subunits and the unproportionally increased expression of α6 subunits, although the two α, two β, and one δ stoichiometry of GABAARs has been shown previously in an exogenous expression system (55). Despite the uncertainty of β subunits, it is likely that the overly expressed GABAAR species in Mecp2-null mice appears to contain δ and α6 subunits.

Tonic GABAA Currents in Mecp2-null Mice

The presence of tonic GABAA currents in LC neurons motivated us to study extrasynaptic GABAARs in Mecp2-null mice. We found that bicuculline-sensitive GABAAergic tonic currents not only existed in Mecp2-null mice but were also enhanced markedly because extrasynaptic GABAAR agonists also elicited significantly larger tonic GABAA currents in Mecp2-null neurons. How the large tonic GABAA currents are produced in Mecp2-null neurons is unclear, but it may result from a relief of direct transcription repression by MeCP2 or its indirect effects on other transcriptional regulators and second messenger systems as a result of Mecp2 disruption. It is also possible that the increased GABAA tonic currents result from compensatory mechanisms for insufficient GABA synaptic input in Mecp2-null neurons (10). Multiple types of neurons are hyperexcitable in Mecp2-null mice, such as hippocampal neurons, neocortical neurons, LC neurons, hypoglossal neurons, etc. (4, 13, 20, 33, 56–58), which is likely to be due to impaired synaptic transmission and intrinsic membrane properties. The highly excitable state of some of these neurons seems to contribute to cognitive defects, motor abnormality, and breathing disturbances (9, 20, 56, 57). Clearly, such an overexcitation in central neurons can be alleviated by GABAergic inhibition, in which excessive extrasynaptic GABAARs are beneficial. Interestingly, this seemingly compensatory up-regulation of GABAergic inhibition has been reported in the synaptic GABAA system (24, 59, 60). In neocortical layer 5 neurons of Mecp2-null mice, an increase of spontaneous IPSCs has been recorded that seems to result from the deficit in GABA release from presynaptic terminals (24). Therefore, the large tonic GABAAergic currents in LC neurons of Mecp2-null mice found in this study might be a compensatory response to the deficient GABA synaptic inhibition.

Although the expression level suggests that the large tonic GABAA currents in Mecp2-null mice are likely to be due to the overexpression of δ subunit-containing receptors, we cannot rule out the possibilities that other expression patterns of GABAARs or a change in GABA affinity could also contribute to the enhanced tonic GABA inhibition in Mecp2-null mice. Nevertheless, RTT patients and Mecp2-null mice with insufficient GABAergic inhibition may benefit from these overexpressed extrasynaptic GABAARs because they may provide alternative targets for pharmaceutical interventions in addition to synaptic GABAARs.

Modulation of Neuronal Activity and Breathing

Experimental evidence suggests that LC neurons play an important role in brain stem CO2 chemosensitivity and breathing regulation (9, 33, 61). Several groups of respiratory neurons and motoneurons are modulated by NE because NE augments cellular excitability via α adrenoceptors (62, 63). This NEergic modulation relies on firing activity and NE biosynthesis in LC neurons. It is possible that there is a homeostatic state between LC neuronal excitability and NE biosynthesis, allowing a stable release of NE at synapses. Although high LC neuronal excitability may lead to more NE release, persistent hyperexcitability may have adverse effects. Hyperexcitability often leads to Ca2+ overload, whereas a persistent elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ can activate a variety of degradative enzymes, including proteases, lipases, and endonucleases (64, 65). These may trigger a cascade of events leading to abnormal cellular activity and metabolic dysfunction, which may, paradoxically, compromise NE biosynthesis.

Mecp2 disruption in mice also causes hyperexcitability in LC neurons and impaired metabolic activity, which is attributable to the defects in neuronal intrinsic membrane properties and insufficient GABA inputs (4, 9, 33). Consistent with these findings, treatment with GABA or diazepam rebalances the hyperexcitability of expiratory neurons and improves the breathing activity in Mecp2-null mice (20, 21). In this study, we found that administration of THIP activates extrasynaptic GABAARs and reduces the excitability of LC neurons as well. Like diazepam, THIP treatment alleviates the breathing abnormalities of Mecp2-null mice. Therefore, excitability stabilization appears to be crucial for the reinstallation of brain stem autonomic function. To avoid potential effects of THIP on arousal states, we monitored animal activity with a video camera during plethysmograph recordings and confirmed that they were not in behavioral sleep.

In Mecp2-null mice, overexcitation of LC neurons may contribute to their metabolic dysfunction by disturbing the homeostasis of NE synthesis, NE production, and NE release by presynaptic terminals. A previous study has reported that, in COS-7 cells, chronic overexcitation impaired homeostatic synaptic plasticity by decreasing AMPA receptor expression (66). Indeed, decreased expression of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine β hydroxylase is known to occur in LC neurons of Mecp2-null mice, leading to insufficient NE biosynthesis (5, 67). THIP application seems to correct LC neuronal hyperexcitability by activation of extrasynaptic GABAARs, as shown in this study, which we believe may stabilize neuronal activity and metabolism, rebalancing the homeostatic state and improving NE biosynthesis.

In conclusion, bicuculline-sensitive tonic currents were recorded from LC neurons, which were increased dose-dependently with increased GABA concentrations. In comparison with WT mice, these GABAAergic tonic currents were increased significantly in Mecp2-null mice. Agonists specific to extrasynaptic GABAARs triggered larger tonic GABAA currents in Mecp2-null LC neurons. Consistently, the δ subunit, the principal component of extrasynaptic GABAARs, was expressed in LC neurons, whose expression level, together with α6 expression in the LC area, became higher in Mecp2-null mice than in the WT, which may contribute to the enhanced tonic GABAA currents. The presence of extrasynaptic GABAARs in Mecp2-null mice seems to allow control of neuronal excitability and breathing abnormalities with GABAAR activators.

Note Added in Proof

Fig. 5 in the Papers in Press version of this article that was published on May 15, 2015 has been revised. Specifically, panels C and G have been merged into panel C, and original panels D and H have been merged into panel D to clarify the presentation. These changes do not affect the interpretation of the results or the conclusions of this work.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-NS-073875.

- RTT

- Rett syndrome

- NE

- norepinephrine

- LC

- locus coeruleus

- GABAAR

- GABAA receptor

- aCSF

- artificial CSF

- IPSC

- inhibitory postsynaptic current

- THIP

- 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol hydrochloride

- DS2

- 4-chloro-N-[2-(2-thienyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-3-yl]]benzamide

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- AP

- action potential

- AHP

- afterhyperpolarization

- SFA

- spike frequency adaptation

- DE

- delayed excitation.

References

- 1. Chahrour M., Zoghbi H. Y. (2007) The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron 56, 422–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lioy D. T., Wu W. W., Bissonnette J. M. (2011) Autonomic dysfunction with mutations in the gene that encodes methyl-CpG-binding protein 2: insights into Rett syndrome. Auton. Neurosci. 161, 55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robinson L., Guy J., McKay L., Brockett E., Spike R. C., Selfridge J., De Sousa D., Merusi C., Riedel G., Bird A., Cobb S. R. (2012) Morphological and functional reversal of phenotypes in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Brain 135, 2699–2710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang X., Cui N., Wu Z., Su J., Tadepalli J. S., Sekizar S., Jiang C. (2010) Intrinsic membrane properties of locus coeruleus neurons in Mecp2-null mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298, C635–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang X., Su J., Rojas A., Jiang C. (2010) Pontine norepinephrine defects in Mecp2-null mice involve deficient expression of dopamine β-hydroxylase but not a loss of catecholaminergic neurons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 394, 285–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zoghbi H. Y., Percy A. K., Glaze D. G., Butler I. J., Riccardi V. M. (1985) Reduction of biogenic amine levels in the Rett syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 313, 921–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ide S., Itoh M., Goto Y. (2005) Defect in normal developmental increase of the brain biogenic amine concentrations in the mecp2-null mouse. Neurosci. Lett. 386, 14–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Viemari J. C., Maussion G., Bévengut M., Burnet H., Pequignot J. M., Népote V., Pachnis V., Simonneau M., Hilaire G. (2005) Ret deficiency in mice impairs the development of A5 and A6 neurons and the functional maturation of the respiratory rhythm. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22, 2403–2412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang X., Su J., Cui N., Gai H., Wu Z., Jiang C. (2011) The disruption of central CO2 chemosensitivity in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 301, C729–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jin X., Cui N., Zhong W., Jin X. T., Jiang C. (2013) GABAergic synaptic inputs of locus coeruleus neurons in wild-type and Mecp2-null mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 304, C844–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. El-Khoury R., Panayotis N., Matagne V., Ghata A., Villard L., Roux J. C. (2014) GABA and glutamate pathways are spatially and developmentally affected in the brain of Mecp2-deficient mice. PloS ONE 9, e92169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fatemi S. H., Reutiman T. J., Folsom T. D., Thuras P. D. (2009) GABA(A) receptor downregulation in brains of subjects with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 39, 223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang L., He J., Jugloff D. G., Eubanks J. H. (2008) The MeCP2-null mouse hippocampus displays altered basal inhibitory rhythms and is prone to hyperexcitability. Hippocampus 18, 294–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boggio E. M., Lonetti G., Pizzorusso T., Giustetto M. (2010) Synaptic determinants of Rett syndrome. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chao H. T., Chen H., Samaco R. C., Xue M., Chahrour M., Yoo J., Neul J. L., Gong S., Lu H. C., Heintz N., Ekker M., Rubenstein J. L., Noebels J. L., Rosenmund C., Zoghbi H. Y. (2010) Dysfunction in GABA signalling mediates autism-like stereotypies and Rett syndrome phenotypes. Nature 468, 263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sigel E., Steinmann M. E. (2012) Structure, function, and modulation of GABAA receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40224–40231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brickley S. G., Mody I. (2012) Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors: their function in the CNS and implications for disease. Neuron 73, 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Farrant M., Nusser Z. (2005) Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 215–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mortensen M., Ebert B., Wafford K., Smart T. G. (2010) Distinct activities of GABA agonists at synaptic- and extrasynaptic-type GABAA receptors. J. Physiol. 588, 1251–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abdala A. P., Dutschmann M., Bissonnette J. M., Paton J. F. (2010) Correction of respiratory disorders in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18208–18213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Voituron N., Hilaire G. (2011) The benzodiazepine midazolam mitigates the breathing defects of Mecp2-deficient mice. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 177, 56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jin X., Zhong W., Jiang C. (2013) Time-dependent modulation of GABAA-ergic synaptic transmission by allopregnanolone in locus coeruleus neurons of Mecp2-null mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 305, C1151–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calfa G., Li W., Rutherford J. M., Pozzo-Miller L. (2015) Excitation/inhibition imbalance and impaired synaptic inhibition in hippocampal area CA3 of Mecp2 knockout mice. Hippocampus 25, 159–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dani V. S., Chang Q., Maffei A., Turrigiano G. G., Jaenisch R., Nelson S. B. (2005) Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12560–12565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Medrihan L., Tantalaki E., Aramuni G., Sargsyan V., Dudanova I., Missler M., Zhang W. (2008) Early defects of GABAergic synapses in the brain stem of a MeCP2 mouse model of Rett syndrome. J. Neurophysiol. 99, 112–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cui N., Zhang X., Tadepalli J. S., Yu L., Gai H., Petit J., Pamulapati R. T., Jin X., Jiang C. (2011) Involvement of TRP channels in the CO2 chemosensitivity of locus coeruleus neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 2791–2801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maguire J., Ferando I., Simonsen C., Mody I. (2009) Excitability changes related to GABAA receptor plasticity during pregnancy. J. Neurosci. 29, 9592–9601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Faul F., Erdfelder E., Lang A. G., Buchner A. (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vardya I., Drasbek K. R., Dósa Z., Jensen K. (2008) Cell type-specific GABA A receptor-mediated tonic inhibition in mouse neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 100, 526–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wójtowicz A. M., Dvorzhak A., Semtner M., Grantyn R. (2013) Reduced tonic inhibition in striatal output neurons from Huntington mice due to loss of astrocytic GABA release through GAT-3. Front. Neural Circuits 7, 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Belelli D., Harrison N. L., Maguire J., Macdonald R. L., Walker M. C., Cope D. W. (2009) Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors: form, pharmacology, and function. J. Neurosci. 29, 12757–12763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith S. S., Shen H., Gong Q. H., Zhou X. (2007) Neurosteroid regulation of GABAA receptors: focus on the α4 and δ subunits. Pharmacol. Ther. 116, 58–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taneja P., Ogier M., Brooks-Harris G., Schmid D. A., Katz D. M., Nelson S. B. (2009) Pathophysiology of locus ceruleus neurons in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. J. Neurosci. 29, 12187–12195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yamashita Y., Matsuishi T., Ishibashi M., Kimura A., Onishi Y., Yonekura Y., Kato H. (1998) Decrease in benzodiazepine receptor binding in the brains of adult patients with Rett syndrome. J. Neurol. Sci. 154, 146–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blatt G. J., Fitzgerald C. M., Guptill J. T., Booker A. B., Kemper T. L., Bauman M. L. (2001) Density and distribution of hippocampal neurotransmitter receptors in autism: an autoradiographic study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 31, 537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Samaco R. C., Hogart A., LaSalle J. M. (2005) Epigenetic overlap in autism-spectrum neurodevelopmental disorders: MECP2 deficiency causes reduced expression of UBE3A and GABRB3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 483–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shivers B. D., Killisch I., Sprengel R., Sontheimer H., Köhler M., Schofield P. R., Seeburg P. H. (1989) Two novel GABAA receptor subunits exist in distinct neuronal subpopulations. Neuron 3, 327–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hamann M., Rossi D. J., Attwell D. (2002) Tonic and spillover inhibition of granule cells control information flow through cerebellar cortex. Neuron 33, 625–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bright D. P., Aller M. I., Brickley S. G. (2007) Synaptic release generates a tonic GABAA receptor-mediated conductance that modulates burst precision in thalamic relay neurons. J. Neurosci. 27, 2560–2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Drasbek K. R., Hoestgaard-Jensen K., Jensen K. (2007) Modulation of extrasynaptic THIP conductances by GABAA-receptor modulators in mouse neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 2293–2300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Song I. S., Savtchenko L., Semyanov A. (2011) Tonic excitation or inhibition is set by GABAA conductance in hippocampal interneurons. Nat. Commun. 2, 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Porcello D. M., Huntsman M. M., Mihalek R. M., Homanics G. E., Huguenard J. R. (2003) Intact synaptic GABAergic inhibition and altered neurosteroid modulation of thalamic relay neurons in mice lacking δ subunit. J. Neurophysiol. 89, 1378–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ye Z., McGee T. P., Houston C. M., Brickley S. G. (2013) The contribution of δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors to phasic and tonic conductance changes in cerebellum, thalamus and neocortex. Front. Neural Circuits 7, 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carver C. M., Wu X., Gangisetty O., Reddy D. S. (2014) Perimenstrual-like hormonal regulation of extrasynaptic δ-containing GABAA receptors mediating tonic inhibition and neurosteroid sensitivity. J. Neurosci. 34, 14181–14197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fleming R. L., Wilson W. A., Swartzwelder H. S. (2007) Magnitude and ethanol sensitivity of tonic GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in dentate gyrus changes from adolescence to adulthood. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 3806–3811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maguire E. P., Macpherson T., Swinny J. D., Dixon C. I., Herd M. B., Belelli D., Stephens D. N., King S. L., Lambert J. J. (2014) Tonic inhibition of accumbal spiny neurons by extrasynaptic α4βδ GABAA receptors modulates the actions of psychostimulants. J. Neurosci. 34, 823–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hanchar H. J., Dodson P. D., Olsen R. W., Otis T. S., Wallner M. (2005) Alcohol-induced motor impairment caused by increased extrasynaptic GABAA receptor activity. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 339–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ferando I., Mody I. (2012) GABAA receptor modulation by neurosteroids in models of temporal lobe epilepsies. Epilepsia 53, 89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Clarkson A. N., Huang B. S., Macisaac S. E., Mody I., Carmichael S. T. (2010) Reducing excessive GABA-mediated tonic inhibition promotes functional recovery after stroke. Nature 468, 305–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Glykys J., Mody I. (2006) Hippocampal network hyperactivity after selective reduction of tonic inhibition in GABA A receptor α5 subunit-deficient mice. J. Neurophysiol. 95, 2796–2807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Prenosil G. A., Schneider Gasser E. M., Rudolph U., Keist R., Fritschy J. M., Vogt K. E. (2006) Specific subtypes of GABAA receptors mediate phasic and tonic forms of inhibition in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 846–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brown N., Kerby J., Bonnert T. P., Whiting P. J., Wafford K. A. (2002) Pharmacological characterization of a novel cell line expressing human α4β3δ GABAA receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 136, 965–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brickley S. G., Revilla V., Cull-Candy S. G., Wisden W., Farrant M. (2001) Adaptive regulation of neuronal excitability by a voltage-independent potassium conductance. Nature 409, 88–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Oginsky M. F., Cui N., Zhong W., Johnson C. M., Jiang C. (2014) Alterations in the cholinergic system of brain stem neurons in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 307, C508–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Patel B., Mortensen M., Smart T. G. (2014) Stoichiometry of δ subunit containing GABAA receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 985–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Moretti P., Levenson J. M., Battaglia F., Atkinson R., Teague R., Antalffy B., Armstrong D., Arancio O., Sweatt J. D., Zoghbi H. Y. (2006) Learning and memory and synaptic plasticity are impaired in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. J. Neurosci. 26, 319–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang W., Peterson M., Beyer B., Frankel W. N., Zhang Z. W. (2014) Loss of MeCP2 from forebrain excitatory neurons leads to cortical hyperexcitation and seizures. J. Neurosci. 34, 2754–2763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Calfa G., Hablitz J. J., Pozzo-Miller L. (2011) Network hyperexcitability in hippocampal slices from Mecp2 mutant mice revealed by voltage-sensitive dye imaging. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 1768–1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Blue M. E., Naidu S., Johnston M. V. (1999) Altered development of glutamate and GABA receptors in the basal ganglia of girls with Rett syndrome. Exp. Neurol. 156, 345–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Na E. S., Monteggia L. M. (2011) The role of MeCP2 in CNS development and function. Horm. Behav. 59, 364–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Viemari J. C., Roux J. C., Tryba A. K., Saywell V., Burnet H., Peña F., Zanella S., Bévengut M., Barthelemy-Requin M., Herzing L. B., Moncla A., Mancini J., Ramirez J. M., Villard L., Hilaire G. (2005) Mecp2 deficiency disrupts norepinephrine and respiratory systems in mice. J. Neurosci. 25, 11521–11530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jin X. T., Cui N., Zhong W., Jin X., Wu Z., Jiang C. (2013) Pre- and postsynaptic modulations of hypoglossal motoneurons by α-adrenoceptor activation in wild-type and Mecp2(−/Y) mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 305, C1080–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. White S. R., Fung S. J., Barnes C. D. (1991) Norepinephrine effects on spinal motoneurons. Prog. Brain Res. 88, 343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Caro A. A., Cederbaum A. I. (2002) Role of calcium and calcium-activated proteases in CYP2E1-dependent toxicity in HEPG2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 104–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Barry M. A., Eastman A. (1992) Endonuclease activation during apoptosis: the role of cytosolic Ca2+ and pH. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 186, 782–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Evers D. M., Matta J. A., Hoe H. S., Zarkowsky D., Lee S. H., Isaac J. T., Pak D. T. (2010) Plk2 attachment to NSF induces homeostatic removal of GluA2 during chronic overexcitation. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1199–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Roux J. C., Panayotis N., Dura E., Villard L. (2010) Progressive noradrenergic deficits in the locus coeruleus of Mecp2 deficient mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 88, 1500–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]