Background: Light-harvesting chlorophyll (LHC) II associates with photosystem (PS) I to form a PS I-LHC II supercomplex.

Results: Treatment of thylakoid membranes with styrene-maleic acid copolymer allows isolation of PS I-LHC II membranes.

Conclusion: LHC II present in these membranes is functionally associated with PS I.

Significance: A significant amount of the PS I present is normally associated with LHC II.

Keywords: electron transfer complex, membrane energetics, membrane protein, photosynthesis, plant biochemistry, PS I-LHC II supercomplex, photosystem I, stryrene-maleic acid copolymer

Abstract

Styrene-maleic acid copolymer was used to effect a non-detergent partial solubilization of thylakoids from spinach. A high density membrane fraction, which was not solubilized by the copolymer, was isolated and was highly enriched in the Photosystem (PS) I-light-harvesting chlorophyll (LHC) II supercomplex and depleted of PS II, the cytochrome b6/f complex, and ATP synthase. The LHC II associated with the supercomplex appeared to be energetically coupled to PS I based on 77 K fluorescence, P700 photooxidation, and PS I electron transport light saturation experiments. The chlorophyll (Chl) a/b ratio of the PS I-LHC II membranes was 3.2 ± 0.9, indicating that on average, three LHC II trimers may associate with each PS I. The implication of these findings within the context of higher plant PS I antenna organization is discussed.

Introduction

Photosystem I (PS I)2 is a light-driven plastocyanin-ferredoxin oxidoreductase that is found in all oxygenic photosynthetic organisms. This membrane protein complex contains at least 17 protein subunits in higher plants (1). In cyanobacteria under standard laboratory growth conditions, PS I is present as a trimer, receiving excitation energy from the phycobilisomes and the interior PS I antennae chlorophyll array associated with the core PsaA and PsaB proteins (2, 3). Under iron-limiting conditions, the phycobilisomes are degraded and PS I receives excitation energy from the IsiA antenna protein complex, which is organized as a ring of 18 IsiA subunits surrounding the PS I trimer (4–6). In higher plants and Chlamydomonas, PS I is present as a monomer. Excitation energy is delivered to the reaction center by an array of intrinsic light-harvesting chlorophyll proteins (LHCs). Four LHC proteins are present in higher plants (Lhca1–Lhca4), whereas nine are present in Chlamydomonas (Lhca1–Lhca9). The higher plant crystal structure of PS I indicates that the Lhca1–Lhca4 proteins are localized to one side of the PS I core complex (1).

During state 1 to state 2 transitions in higher plants, a subpopulation of the LHC proteins believed to be normally associated with the PS II complex can dissociate and become associated with PS I, forming a PS I-LHC II supercomplex (for review see Ref. 7). These supercomplexes are typically observed during blue native gel electrophoresis in the presence of low concentrations of the detergents dodecyl maltoside and/or digitonin, or can be isolated in low yield by ultracentrifugation on sucrose density gradients after membrane solubilization with these detergents (8, 9). It is unclear, however, if this low apparent yield is physiologically representative of the abundance of the PS I-LHC II supercomplex or if this supercomplex is unstable in the presence of detergent. It has been proposed that a significant amount of LHC II is associated with PS I even under State 1 conditions (9, 10). These results indicate that up to 40–65% of the PS I solubilized by digitonin from thylakoids is associated with a single LHC II trimer. It has been suggested that, under long day/high light intensity growth conditions, PS I can become acclimatized and associate constitutively with LHC II (10). Interestingly, during state 1 to state 2 transitions in Chlamydomonas, a large proportion of the LHC II antenna, including CP29 and, possibly, CP26, as well as multiple LHC II trimers associate with PS I (11, 12).

Recently, the use of detergent-less solubilization procedures for membrane proteins has found increasing interest (for reviews see Refs. 13–15). Styrene-maleic acid (SMA) copolymers appear to be quite useful in this regard. This material forms nanodiscs, which are ∼100 Å in diameter when mixed with artificial phospholipid bilayers (16). Solubilization of biological membranes with SMA yields similarly sized nanodiscs containing both membrane lipids and membrane proteins. Interestingly, the lipid profile of these nanodiscs is very similar, if not identical, to the lipid profile of the solubilized membrane (17, 18). This material has been used to solubilize bacteriorhodopsin, which had been incorporated into DMPC vesicles (19) and mitochondrial membranes, with cytochrome oxidase being incorporated into the SMA nanodiscs (17). Recently, the bacterial reaction center from Rhodobacter sphaeroides has also been solubilized using these methods (18). A generalized molecular model for the solubilization of biological membranes with SMA has also been presented (15). Briefly, it was proposed that initially the SMA binds to the biological membrane in a process driven by the hydrophobic interaction between the styrene groups and the lipid acyl chains. This is followed by insertion of the SMA into the lipid bilayer, which leads to destabilization of the membrane. Finally, nanodisc formation occurs, with the SMA located on the periphery of the nanodisc, with the styrene groups being oriented between the acyl chains of the membrane lipid.

It should be noted that membrane protein complexes with diameters larger than about 100 Å would not be expected to be solubilized efficiently into SMA nanodiscs. Interestingly, the PS I complex exhibits dimensions of ∼140 × 180 Å when measured at the surface of the thylakoid membrane (1). Consequently, it would not be expected for either the PS I complex, or larger PS I supercomplexes containing LHC II to be incorporated into nanodiscs during the SMA solubilization of thylakoid membranes. In this article we report the isolation of a thylakoid membrane fragment preparation highly enriched in a PS I-LHC II supercomplex, which was obtained after stacked thylakoid membranes were solubilized with SMA.

Experimental Procedures

PS II-LHC II Membrane Isolation

Thylakoids were isolated from market spinach by blending in a buffer containing 20 mm Tricine-NaOH, pH 8.4, 0.45 m sorbitol, 10 mm EDTA, 0.1% BSA, and 1% polyvinylpyrolidone. The homogenate was filtered through two layers of cheesecloth and one layer of Miracloth (Calbiochemical Co.) and the thylakoids were pelleted at 2,500 × g for 5 min. After washing twice in a wash buffer containing 0.3 m sorbitol, 5 mm MgCl2, and 20 mm Tricine-NaOH, pH 7.6, the thylakoids were resuspended in the same buffer at 3.0 mg of Chl/ml. This suspension was brought to 3% styrene-maleic acid copolymer from a 25.6% stock solution (SMA® 3000HNa, a kind gift from Cray Valley USA LLC) and incubated for 20 min on ice in the dark with occasional stirring. The solubilized thylakoids were then centrifuged at 34,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was carefully removed and filtered through a 0.2-μm filter (Millipore Corp.) and then applied to 10–20% sucrose density gradients prepared in wash buffer. After centrifugation for 18 h at 100,000 × g (Beckman SW 28 rotor), two chlorophyll-containing bands, B1 and B2, were carefully removed from the gradient and the pellet, which is the subject of this article, was resuspended in wash buffer at 1 mg of Chl ml−1.

For gel filtration analysis, the resuspended pellet was applied to a Sepharose 6B column (3 × 90 cm) that had been previously equilibrated with a buffer containing 20 mm Tricine-NaOH, pH 8.0, and 20 mm NaCl. For analytical separations, 1 ml of the pellet suspension was applied to the column; for preparative separations the volume was 5 ml. The column was eluted at a flow rate of 1 ml/min with a total run volume of 500 ml. One chlorophyll-containing band was observed, which was then concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration. In some experiments, the pellet suspension was solubilized with 1% β-d-dodecyl maltoside (DM) for 15 min and then applied to the same gel filtration column that had been equilibrated with 20 mm Tricine-NaOH, pH 8.0, 20 mm NaCl, and 0.03% DM. In these experiments, two chlorophyll-containing bands were observed; these were designated SB1 and SB2 and the appropriate fractions were concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration.

It should be noted that this procedure works very poorly for Arabidopsis thylakoids for reasons, at this point in time, we cannot explain. Solubilized chlorophyll yield is extremely low and the putative PS I-LHC II membranes obtained after ultracentrifugation contain significant contamination from other thylakoid membrane protein complexes.

Steady State P700 Measurements

Measurements of steady state P700 oxidation and reduction were performed with the JTS-10 kinetic spectrometer (Bio-Logic Science Instruments) in absorbance mode using the “pulse of dark” method. Either spinach leaves or liquid phase samples (20–50 μg of Chl/ml) were incubated in the dark for 5 min prior to each measurement. Samples were illuminated and the absorbance changes at 705 nm were monitored to assess the oxidation of the PS I P700 reaction center during illumination, followed by reduction of P700+ in the subsequent dark period. To specifically excite PS I and the LHC I antenna, a 720-nm actinic light source was used (1,400 μmol of photons m−2 s−1). To excite LHC II as well as PS I-LHC I, a broadband orange light source with a peak of 630 nm was used (940 μmol of photons m−2 s−1). Data were analyzed using Origin version 8.1 and proprietary software provided by Bio-Logic Scientific Instruments.

Steady State Room Temperature and 77 K Fluorescence

Fluorescence measurements at room temperature and at 77 K were collected on a home-built fluorometer. Excitation at 470 nm was provided with a band pass filter, which delivered 80 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 at the sample cuvette. The detector was protected by a 550–800-nm long pass filter. The fluorescence emission from 650 to 800 nm was detected with a concave grating spectrometer and CCD detector (StellarNet Black Comet®) with an integration time of 100 ms per spectrum with 10 spectra averaged per measurement. The spectra were background corrected and normalized. For the 77 K measurements, samples were suspended in 20% glycerol, 20 mm Tricine-NaOH, pH 8.0, and 20 mm NaCl at 10 μg of Chl/ml. For room temperature measurements the glycerol was omitted.

PS I Electron Transport

PS I electron transport was performed by polarography (Hansatech Co.). The assay buffer contained 100 mm sorbitol, 50 mm Tricine-NaOH, pH 8.0, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm NaCl, 5 mm sodium ascorbate, 100 μm 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol, 50 μm methyl viologen, 20 μm 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea, and 10 mm KCN. Illumination was provided by a computer-controlled red light-emitting diode array.

Electrophoresis and Protein Detection

Native electrophoresis in the absence of detergent was performed in a 1% agarose gel (agarose I-B, low EEO, Sigma Co.) in a horizontal apparatus and using a continuous buffer (0.05 m BisTris-NaOH, pH 7.0) for 3–4 h at 4 °C.

Lithium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed under conditions described by Delepelaire and Chua (20, 21) using gradient 12.5–20% polyacrylamide gels. The resolved polypeptides were electroblotted onto PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P®, Millipore Corp.). After blocking for 2 h with 5% nonfat dry milk in TS buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4), the blots were washed extensively with TS buffer and then incubated with diluted primary antibody in TS buffer + 1% bovine serum albumin overnight. This was followed by washing in TS buffer and incubation with either anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-peroxidase conjugate (Sigma) diluted in TS buffer + 1% bovine serum albumin for 2–4 h. After washing with TS buffer, the labeled protein was detected using either chemiluminescence (SuperSignal® West Pico, Pierce Chemical Co.) or 4-chloro-1-napthol. Cytochrome f was detected directly by chemiluminescence (22).

Results

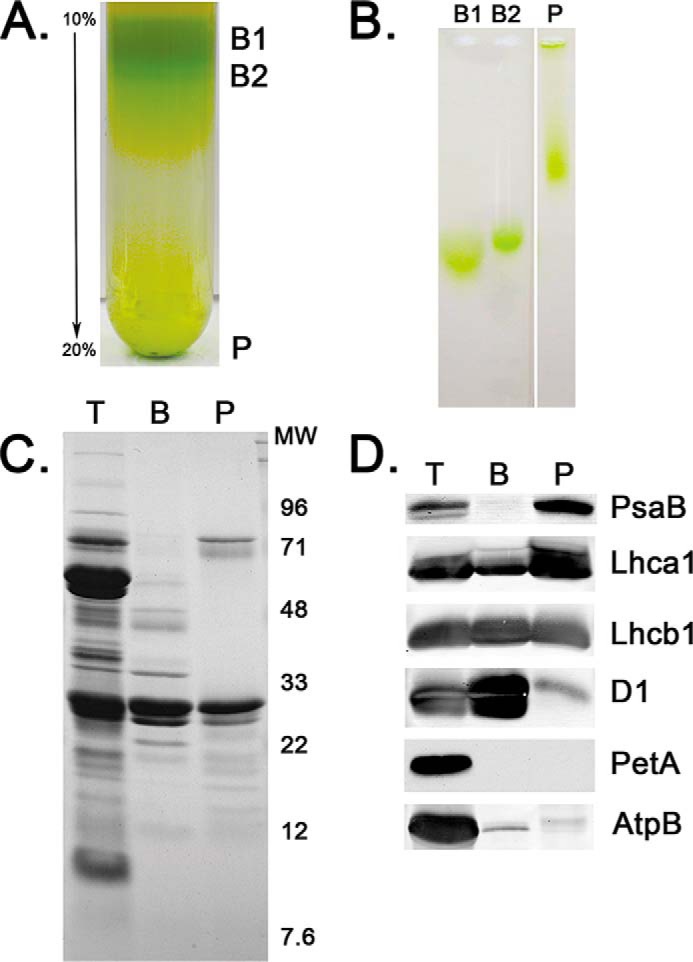

Fig. 1A illustrates the sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation of solubilized stacked thylakoid membranes. Two low density bands were partially resolved and are labeled B1 and B2 and a dense pellet (P) was also observed. P appeared to be an unsolubilized membrane fraction. A similar pattern was observed using non-detergent electrophoresis in 1% agarose of these three fractions (Fig. 1B). B1 and B2 were both present as rapidly migrating species, whereas P exhibited significantly slower migration. It should be noted that the pore size of 1% agarose has been estimated to be 200–400 nm (23, 24). Consequently, all of the fractions examined in this experiment appear to be smaller than this value. B1 and B2 exhibit complex polypeptide profiles (data not shown) and are the object of further investigations. The characteristics of the high-density fraction P are the subject of this article. Interestingly, P was obtained in very high yield, 24 ± 8% based on starting Chl (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Isolation and characterization of PS I-LHC II membranes. A, typical 10–20% sucrose density gradients. Three Chl-containing fractions were observed, two of low density, labeled B1 and B2, and a high-density pellet labeled P, which is the PS I-LHC II membrane fraction. B, non-detergent, native electrophoresis in 1% agarose of B1, B2, and P. B1 and B2 exhibit high mobility, whereas P is much less mobile. All three Chl-containing fractions enter the gel and, consequently, are smaller than the pore size of the agarose (≈400 nm). C, Coomassie Blue stain of a 12.5–20% lithium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE analysis of thylakoids (T), PS II membranes (BBYs) (B), and the PS I-LHC II membranes (P). Molecular weight markers are shown to the right. D, Western blot analysis of selected proteins separated as in C. PsaB, core reaction center of PS I; Lhca1, component of the LHC I antenna for PS I; Lhcb1, component of the mobile LHC II antenna; D1, core reaction center protein for PS II; PetA, cytochrome f; and, AtpB, β-subunit of the ATP synthase. Lanes are labeled as in C.

TABLE 1.

Selected characteristics of the photosynthetic preparations examined

| Fraction | Chl a/b | Yield from starting chl | PS I electron transport | LI50a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | μmol O2 mg chl−1 h−1 | μmol photons m−2 s−1 | ||

| Thylakoids | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 100 | −192 ± 54 | ≤50 |

| PS I-LHC II membranes | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 24 ± 8 | −144 ± 16 | ≤50 |

| SB1 | 7.8 ± 1.5 | NDb | −404 ± 150 | 125 |

| SB2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | ND | ND | ND |

| BBY | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 23 ± 2 | ND | ND |

a Light intensity at 50% maximal electron transport rate.

b ND, not determined.

The polypeptide profile of the sucrose density gradient pellet (P) in comparison to thylakoids and PS II membranes (BBY (25)), is shown in Fig. 1C. In comparison to thylakoids, P is highly depleted of proteins in the 28–60 kDa region, exhibiting major bands at 65–72 kDa (PsaA/PsaB), 22–26 kDa (light-harvesting chlorophyll proteins) with numerous lower mass proteins in the 10–22 kDa region. Most of the proteins enriched in PS II membranes are depleted in P, and vice versa. The principal exception is a strong light-harvesting chlorophyll protein band that is abundant in both P and BBY samples. Upon comparison of the polypeptide profile of P with published examples of PS I preparations (26–28), it is evident that, with the exception of this large amount of light-harvesting chlorophyll proteins, the P material appears to consist predominantly of PS I. Recently, the isolation of detergent-solubilized PSI-LHC II particles has been reported (9, 10). These preparations contain, in addition to the PS I core and LHC I antennae components, LHC II. The polypeptide profiles of these preparations are very similar to that which we observe for the P material, although we observe a higher apparent yield of light-harvesting chlorophyll proteins in our preparation. “Western” blots (Fig. 1D) were used to examine a number of specific proteins associated with PS II (PsbA and Lhcb1), the cytochrome b6/f complex (PetA), CF1-CFo (AtpB), and PS I (PsaB and Lhca1). P is highly depleted of PsbA, PetA, and AtpB, indicating that this membrane fraction contains little PS II, cytochrome b6/f complex, or CF1-CFo, respectively. P is enriched in PsaB and Lhca1 and additionally contains a large amount of Lhcb1. We will present evidence that the P is a PSI-LHC II-enriched membrane fraction.

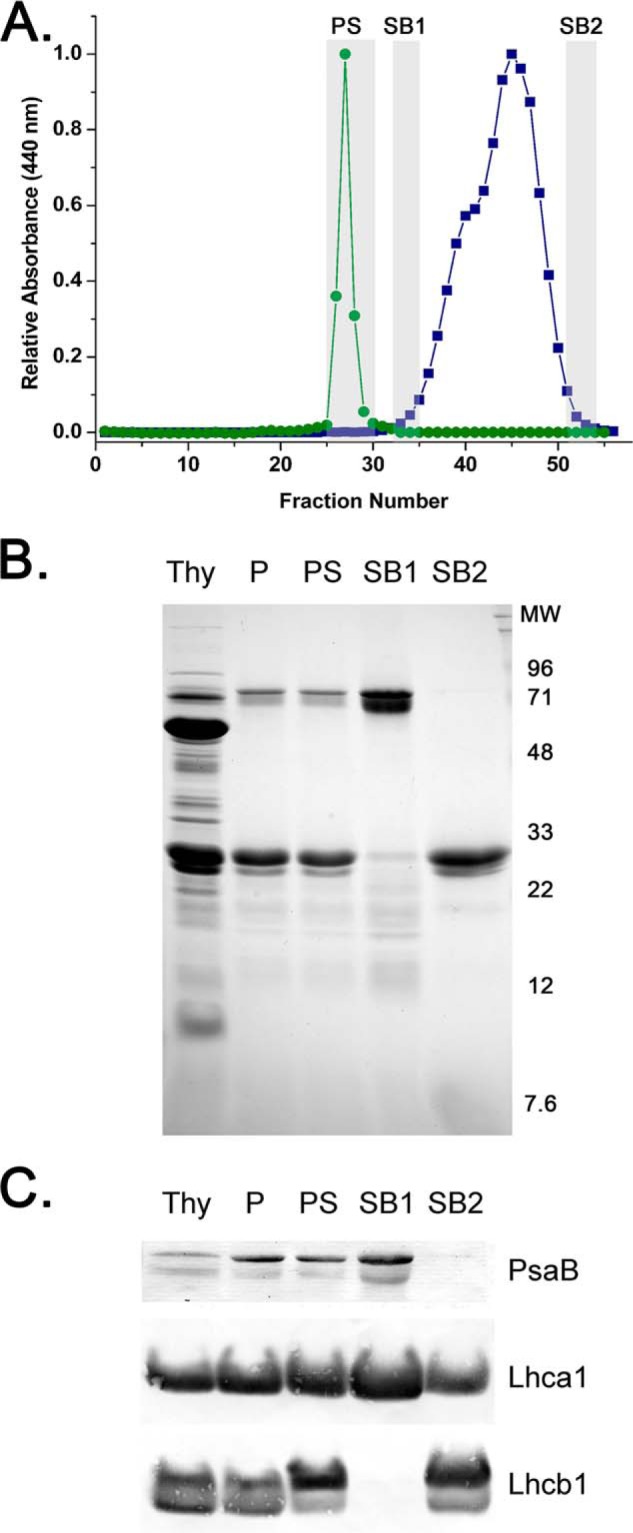

Fig. 2 illustrates a Sepharose 6B (exclusion limit ≈5 × 106 daltons) separation of the putative PSI-LHC II membranes that migrate as a sharp symmetrical green band (Fig. 2A) eluting in fraction 27; blue dextran with a molecular mass of 2 × 106 elutes in fraction 30 (data not shown). This indicates that the putative PSI-LHC II membranes exhibit a higher apparent molecular mass than the blue dextran. Analysis of the polypeptide pattern of fractions obtained from the Sepharose 6B column shows that the protein makeup of the putative PSI-LHC II membranes was the same both before and after fractionation on Sepharose 6B (Fig. 2B). This indicates that both the PS I-associated proteins and the LHC II are both present in a high molecular mass fraction.

FIGURE 2.

Gel filtration analysis on Sepharose 6B of the PS I-LHC II membranes before and after treatment with β-d-dodecyl maltoside. A, typical elution profile of the PS I-LHC II membranes either in the absence of detergent (labeled PS, green, closed circles) or after treatment with 1% detergent (blue, closed squares). The leading and trailing edges (labeled SB1 and SB2, gray rectangles) of the two poorly resolved Chl-containing peaks observed in the presence of detergent were collected for further analysis. The same column (3 × 90 cm) was used in both experiments. The elution buffer consisted of 20 mm Tricine-NaOH, pH 8.0, and 20 mm NaCl with, in the case of the detergent treatment, the addition of 0.03% β-d-dodecyl maltoside. Detection of Chl was at 440 nm. B, Coomassie Blue stain of the gel filtration fractions analyzed on a 12.5–20% lithium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE gel. Thy, thylakoids; P, PS I-LHC II membranes; PS, PS I-LHC II membranes after passage through gel filtration column in the absence of detergent; SB1, fractions at the leading edge of the higher apparent molecular mass peak after detergent treatment; SB2, fractions at the trailing edge of the lower apparent molecular mass peak after detergent treatment. C, Western blot analysis of selected proteins in these fractions after separation as in B. PsaB, core reaction center of PS I; Lhca1, component of the LHC I antenna for PS I; Lhcb1, component of the mobile LHC II antenna. Lanes are labeled as in B.

If the putative PSI-LHC II membranes are solubilized with 1% DM and fractionated on the same Sepharose 6B column (previously equilibrated with a 0.03% DM-containing buffer) a very different pattern is observed. Two partially resolved green peaks are observed and these elute significantly later than do the putative PSI-LHC II membranes (in the absence of detergent). This indicates that both green bands exhibit lower apparent molecular mass than the putative PSI-LHC II membranes (Fig. 2A). Because these bands were only partially resolved, the leading and trailing edges of these peaks (labeled SB1 and SB2, respectively) were harvested and concentrated by ultrafiltration. In Fig. 2B, the polypeptide pattern of these fractions (thylakoids (T), the putative PSI-LHC II membranes (P), and the putative PSI-LHC II membranes after Sepharose 6B chromatography (PS), SB1 and SB2) are shown loaded on a constant Chl basis. Comparison of the putative PSI-LHC II membranes (P and PS) to the green fractions obtained after DM treatment indicated that the SB1 fraction is depleted of light-harvesting chlorophyll proteins and enriched in the 65–75-kDa polypeptides and lower apparent mass bands in the 10–20 kDa range. The SB2 fraction is depleted of the 65–75-kDa polypeptides and most of the proteins in the 10–20-kDa region, whereas being enriched in the light-harvesting chlorophyll proteins. Western blot analysis of these fractions is illustrated in Fig. 2C. Antibodies against PsaB were used to identify fractions containing the reaction center of PS I, antibodies against Lhca1 were used to identify fractions containing the LHC I antenna, and antibodies against Lhcb1 were used to identify fractions containing the LHC II antenna. It should be noted that Lhcb1 has been identified as a mobile component of the LHC II antennae, which has been considered to be normally associated with PS II. The thylakoids and both putative PSI-LHC II membrane fractions (P and PS) contain PsaB, Lhca1, and Lhcb1. The SB1 fraction is enriched in PsaB and Lhca1 and contains no detectable Lhcb1, whereas the SB2 fraction is highly depleted of PsaB, containing principally Lhcb1 and a smaller amount of Lhca1. These results indicate that the putative PSI-LHC II membranes contain the PS I reaction center and components of the LHC I and LHC II antennae. After detergent treatment the LHC II antennae component dissociate from the putative PSI-LHC II membranes, yielding SB1, an apparent PS I-LHC I detergent complex. Because the putative PSI-LHC II membranes contain all three components (PS I, LHC I, and LHC II), they appear to be localized in a non-detergent-containing putative PS I-LHC II supercomplex. However, if this is the case, then a functional association of LHC II with the PS I-LHC I complex must be demonstrated.

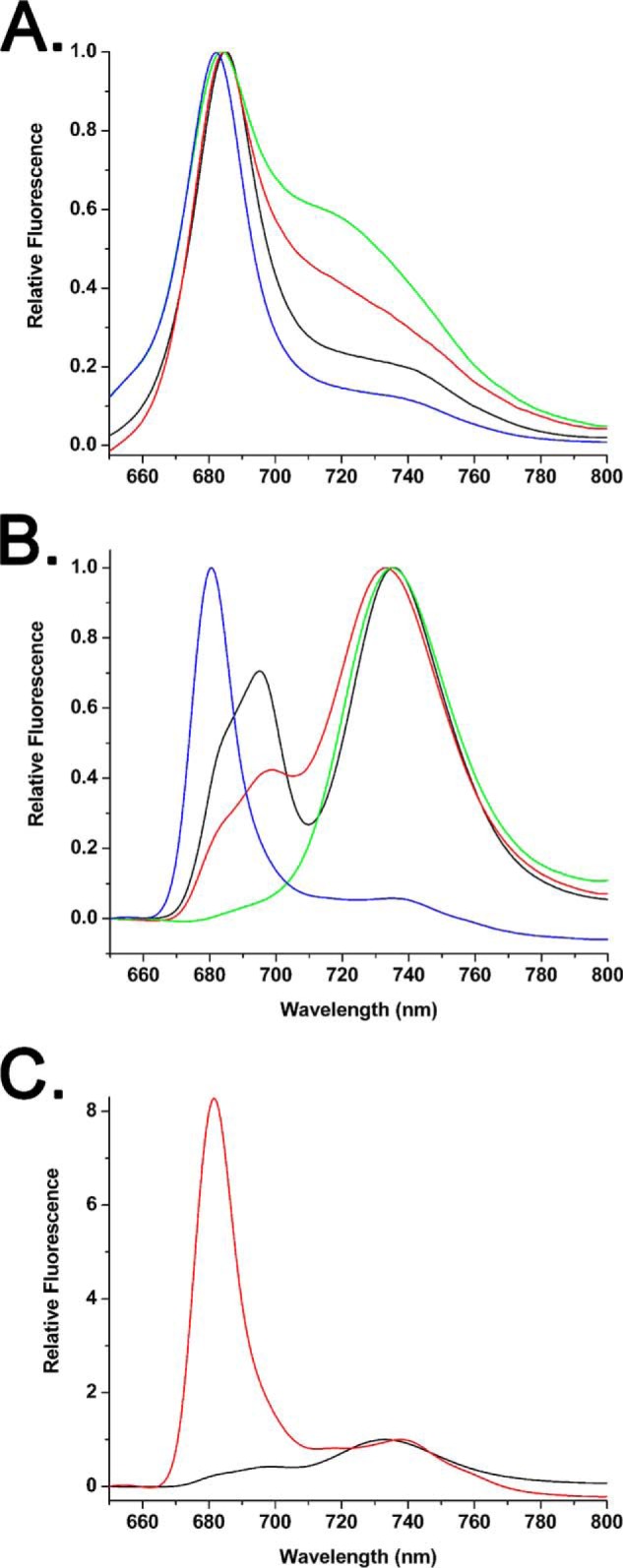

To examine the association of the LHC II antenna with PS I we examined both room temperature and 77 K fluorescence emission spectra. These results are illustrated in Fig. 3. Typical room temperature fluorescence is shown in Fig. 3A. Thylakoids exhibit a peak at 685.5 nm with a pronounced shoulder in the 725–750 nm region, as has previously been reported in the supporting material (29). The putative PS I-LHC II membranes exhibit a fluorescence maximum at 685 nm and an enhanced yield of the 725–750 nm emission. Qualitatively, this appears very similar to the room temperature fluorescence emission spectra reported for Arabidopsis stroma lamellae (30). The DM-dissociated SB1 fraction, which contains predominantly PS I, exhibited a fluorescence maximum at 684 nm and an enhanced 720–750 nm emission when compared with either thylakoids or the putative PS I-LHC II membranes. This was very similar to that observed for the Arabidopsis PS I/200 DM preparation (31). Finally, SB2, which contains predominantly LHC components, exhibited a 682-nm emission maximum and decreased fluorescence yield in the 720–750-nm region and is qualitatively quite similar to the Lhcb1–3 complexes previously described (32).

FIGURE 3.

Typical room temperature and 77 K fluorescence emission spectra. A, room temperature spectra of thylakoids (black), the PS I-LHC II membranes (red), and the detergent-solubilized gel filtration fractions SB1 (green) and SB2 (blue). B, 77 K spectra, labeling is as in A. C, 77 K emission spectra of the PS I-LHC II membranes before (black) and after (red) treatment with 1% β-d-dodecyl maltoside. Both of these spectra are from the same sample and are normalized to the PS I emission peak at 730–740 nm. In all panels, fluorescence excitation was at 470 nm with a light intensity of 80 μmol of photons m−2 s−1; the Chl concentration of all samples was 10 μg of Chl ml−1.

Typical 77 K fluorescence spectra are shown in Fig. 3B. The thylakoids exhibit peaks at 695 (with a pronounced shoulder at 685 nm) and 735 nm. The 685 and 695 nm peaks arise from PS II, whereas the 735-nm peak originates from PS I. The putative PS I-LHC II membranes exhibit a major peak at 730 nm, with a lower intensity peak at 699 nm and a shoulder at 680 nm. Although the major peak arises from PS I the origin of the 699 nm feature is unclear, although it may arise from a small proportion of aggregated LHC II (33). It is unlikely that this feature originates from PS II contamination because the amount of PS II in this fraction appears to be quite low (Fig. 1, C and D) and the emission peak is significantly red-shifted vis à vis the 695 nm emission from PS II. The 680-nm shoulder may arise from a small proportion of LHC II trimers that are not energetically coupled to PS I (see below). SB1 exhibits an emission spectrum characteristic of PS I-LHC I (9) and SB2 exhibits a spectrum characteristic of purified LHC II trimers (33). In Fig. 3C, a 77 K emission spectrum was collected from the putative PS I-LHC II membranes, the same sample was then treated with 1% DM for 15 min and a subsequent 77 K emission spectrum was collected. These data were normalized to the PS I emission band of each sample. Treatment with DM leads to the formation of a large 680-nm emission peak, which is indicative of uncoupled LHC II trimers. This provides strong evidence that the LHC II present in the PS I-LHC II membranes is energetically coupled to PS I.

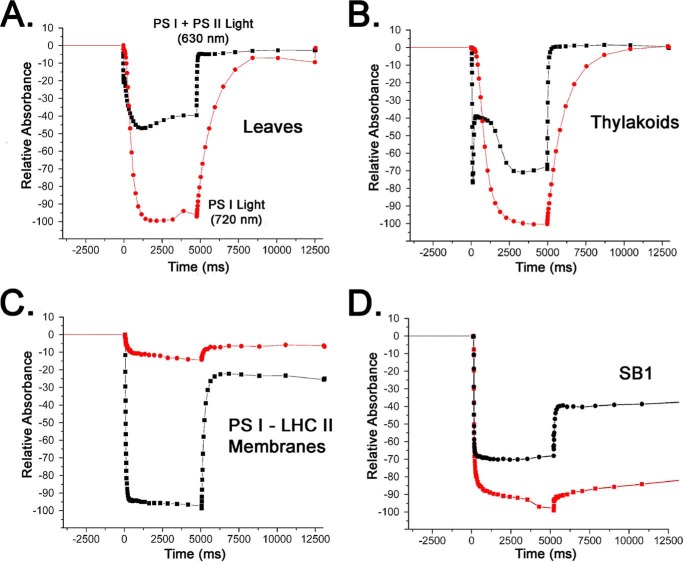

To further examine this possibility we evaluated P700+ formation upon illumination with 630 and 720 nm actinic illumination. 630 nm light is efficiently harvested by both PS I and PS II, whereas 720 nm light is efficiently harvested only by PS I. Fig. 4 illustrates typical P700 photooxidation and reduction patterns in leaves, thylakoids, and P upon 5 s actinic illumination with 630 nm light. In leaves (Fig. 4A), 720 nm light is more efficient at eliciting steady state P700+ formation than 630 nm light. Because this is a steady state experiment, under 630 nm illumination conditions electrons are available from PS II, which reduce P700+ to P700, with a consequent reduced steady state accumulation of P700+. As expected, under this illumination condition, the reduction of P700+ was very rapid in the dark. Under 720 nm illumination conditions, only a limited flow of electrons, which are delivered via cyclic electron transport are available to reduce P700+, leading to a larger steady state accumulation of this species with a concomitant slow reduction of P700+ in the dark. In thylakoids (Fig. 4B) a qualitatively similar pattern is observed both with respect to P700 oxidation and reduction under both illumination conditions. A markedly different pattern is observed for P700 oxidation and reduction in the PSI-LHC II membrane sample (Fig. 4C). Illumination with 630 nm light leads to the formation of a large amount of P700+, whereas only a small amount of P700+ is formed with 720 nm illumination. These results indicate that 630 nm light is highly efficient at providing excitation energy for P700 oxidation in the PS I-LHC II membranes. In Fig. 4D, SB1 was examined. In this sample, which appears to contain principally PS II (Fig. 2, B and C), both 630 nm light and 720 nm light appear nearly equivalently effective in the formation of P700+. These results provide additional evidence that the LHC II present in the PS I-LHC II membranes is functionally coupled to PS I and is very effective in providing excitation energy leading to P700+ formation.

FIGURE 4.

Typical steady state P700 oxidation measurements examining the relative efficiency of PS I + PS II actinic light and PS I, only actinic light. A, spinach leaf; B, thylakoids; C, PS I-LHC II membranes; and D, detergent-treated SB1 fraction. Black squares, PS I + PS II light (630 nm, 940 μmol of photons m−2 s−1) actinic illumination, red circles, PS I light, only (720 nm, 1400 μmol of photons m−2 s−1) actinic illumination. In each case, the same sample was examined sequentially under both actinic light conditions. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that the order of the light treatments had no effect on the result.

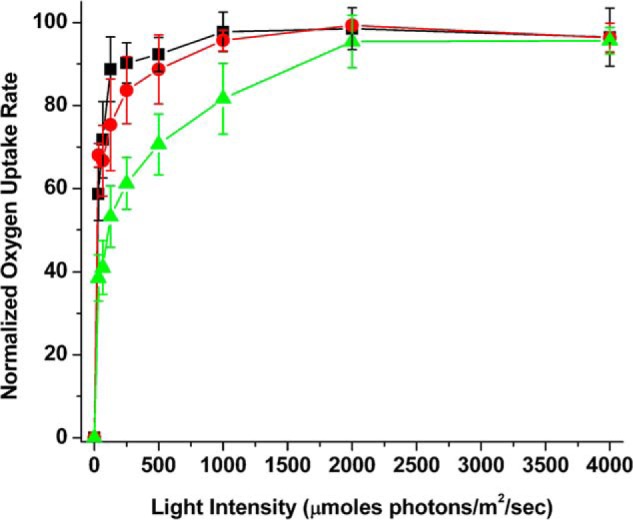

Fig. 5 illustrates the PS I-dependent electron transport (2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol/ascorbate to methyl viologen) of thylakoids, PS I-LHC II membranes, and SB1 at varying light intensities. The light saturation curves are very similar for thylakoids and the PS I-LHC II membranes. This indicates that PS I in thylakoids and in the PS I-LHC II membranes appear to have similar effective antennae sizes. The light intensity at which ½ maximal PS I activity was observed (LI50) was ≤50 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 in both samples. Treatment of the putative PS I-LHC II membranes with 1% DM allowed isolation of SB1, which contained no detectable Lhcb1 (Fig. 2C). The light saturation curve for SB1 (PS I) exhibited significantly different light saturation characteristics. Removal of the LHC II antenna by detergent treatment yields PS I activity, which saturates at a much higher light intensity, exhibiting a LI50 of about ≈125 μmol of photons m−2 s−1. These results provide additional evidence that the antennae components present in the PS I-LHC II membranes are efficiently delivering excitation energy to the PS I reaction center.

FIGURE 5.

Light saturation of PS I electron transport activity. Electron transport rates for the samples were determined over a light intensity range of 0 to 4,000 μmol of photons m−2 s−1. Rates were normalized to the maximal observed rate for each sample type. Black squares, thylakoids; red circles, PS I-LHC II membranes; and, green triangles, detergent-treated SB1 fraction. In some cases, the error bars are smaller than the symbols. n = 3–4, error bars ± 1.0 S.D.

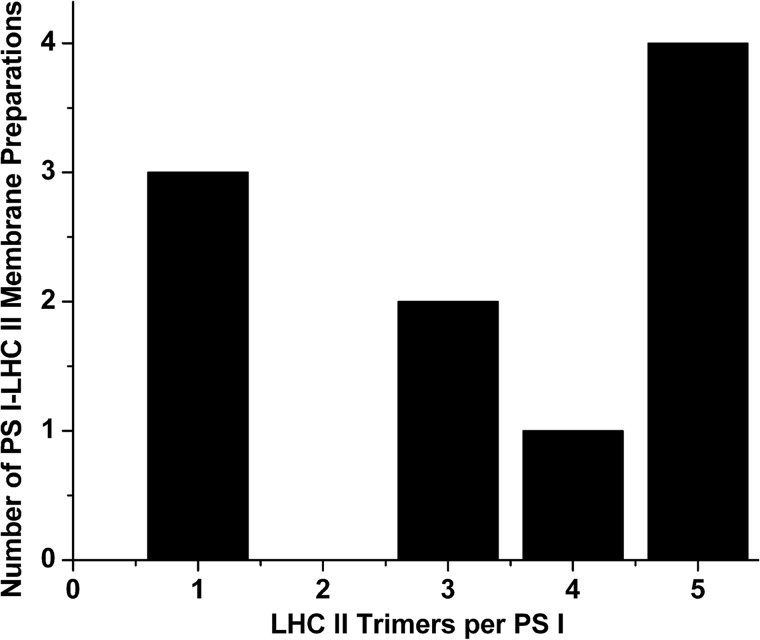

Analysis of the Chl a/b ratio (Table 1) can provide semi-quantitative information concerning the number of LHC II trimers present in the PSI-LHC II membrane preparation. Using the calculations presented by Galka et al. (9) and making their assumptions that PS I (including LHC I) contains 155 Chl a and 19 Chl b, that an LHC II trimer contains ∼24 Chl a and 18 Chl b, and that all of the additional Chl present in the PSI-LHC II membrane preparation is in the LHC II trimer state, we calculate that the PSI-LHC II membrane preparation, which exhibits a Chl a/b ratio of 3.2 ± 0.9 (Table 1), contains on average 3 LHC II trimers per PS I with an effective antennae size of about 300 Chl/P700. These results, consequently, differ somewhat from previous reports examining PS I-LHC II supercomplexes prepared using detergents. Kouřil et al. (34) identified a single LHC II trimer associated with PS I in unfractionated digitonin-solubilized thylakoid membranes using single particle analysis. Galka et al. (9) also demonstrated that one LHC II trimer was associated with PS I in a PS I-LHC II supercomplex prepared using low concentrations of α-d-dodecyl maltoside. In both of these studies the effective antennae size for PS I would be ≈216 Chl/P700. The association of LHC II trimers with PS I, however, is known to be very sensitive to detergents. We hypothesize that two populations of LHC II trimers exist, one that is relatively more stable to detergents and one that is more labile. Because our PS I-LHC II membranes have not been exposed to detergents, the association of both populations of LHC II trimers with PS I may be maintained. Interestingly, in a non-detergent fractionation of thylakoids by sonication followed by countercurrent distribution (35), it was estimated that the effective antennae size for PS Iα, the fraction of PS I associated with LHC II, was 302 Chl/P700, a value identical to that obtained for PS Iα using EPR (36). Within error, these values are also identical to our observations for the PS I-LHC II membranes.

It must be recognized that all of these measurements are population averages for the composition of PS I-LHC II supercomplexes. With respect to the PS I-LHC II membranes we describe, the composition appears quite variable (hence the large standard deviation). Examination of 10 independent PS I-LHC II membrane preparations with respect to the number of calculated LHC II trimers/PS I is shown in Fig. 6. The two most commonly observed ratios are five trimers/PS I and one trimer/PS I.

FIGURE 6.

Trimer stoichiometry variability of PS I-LHC II membranes. Results from 10 independent PS I-LHC II membrane preparations are presented. Calculation of the number of LHC II trimers per PS I were performed as in described in Ref. 9. The Chl a/b ratios for these preparations ranged from 2.5 to 4.9 (mean = 3.3 ± 0.9). These observed Chl a/b ratios deviated an average of 4% from the calculated integer values for LHC II trimers per PS I.

Discussion

The PS I-LHC II membrane preparation that we describe is depleted of PS II, the cytochrome b6/f complex, and CF1-CFo, and appears analogous to the PS II membrane preparation commonly referred to as BBYs (25), and is obtained in similarly high yields. It should be noted that this preparation differs significantly from stromal thylakoid preparations obtained by sonication (37) or treatment with mild detergents such as digitonin (34, 38). Such stromal thylakoid preparations contain, in addition to PS I and its antennae, the cytochrome b6/f complex, CF1-CFo, and a fraction of PS II, which is undergoing assembly/repair (39, 40). None of these other complexes appear to be present in significant quantities in the PS I-LHC II membranes. This raises the intriguing possibility that these other thylakoid membrane protein complexes may have been solubilized into SMA nanodiscs. This possibility is currently under active investigation.

The PS I-LHC II membranes contain a large amount of LHC II. Interestingly, the observed Chl a/b ratio of these membrane fragments indicates that they may contain multiple LHC II trimers per PS I. The two most commonly observed compositions are five trimers/PS I and one trimer/PS I. The cause of this variability is unclear. However, because we have used market spinach in these investigations it is quite possible that different growth conditions may affect the trimer/PS I ratio observed in these membranes. These observations highlight the probability that the overall makeup of the PS I-LHC II supercomplexes appears to be quite fluid in nature. Our observation that a relatively large number of LHC II trimers can apparently associate with PS I (at least under some conditions) is clearly reminiscent of the situation in Chlamydomonas under state 2 conditions (11, 12).

Although it is unclear if all of the LHC II trimers present in the PS I-LHC II membranes can deliver excitation energy to the PS I reaction center, our results certainly indicate that a high proportion of LHC II is functionally coupled to PS I. The absence of a strong 680-nm fluorescence emission peak at 77 K appears to indicate that most of the LHC II present in the PSI-LHC II membrane preparation appears to be coupled to PS I. The LHC II can be released by detergent treatment, with the subsequent appearance of a strong 680-nm emission band. Additionally, we observe that 630-nm light, which is absorbed by both the PS I and PS II antennae, is much more efficient than 720-nm light in supporting P700+ formation in the PSI-LHC II membrane preparation. After detergent treatment, the 630-nm actinic light is much less effective at supporting P700+ formation. Finally, our finding that the PS I-dependent electron transport activity of both the thylakoids and PS I-LHC II membrane preparation exhibits an LI50 of ≤50 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, compared with an LI50 of the DM-solubilized SB1 with an LI50 of ≈125 μmol of photons m−2 s−1. This indicates that a larger antenna is associated with PS I in both thylakoids and the PSI-LHC II membranes and that a much smaller antenna is present after detergent treatment.

Although many investigators have assumed that the LHC II is normally a component of the PS II antenna system that dissociates from PS II and associates with PS I under state 2 conditions, Wientjes et al. (10) found that under all growth light conditions examined, a significant proportion of PS I was associated with LHC II (40–65%). Galka et al. (9) came to a similar conclusion and suggested that the mobile LHC II trimers could even be considered integral to the PS I antenna, and under state 1 conditions is displaced and associates with PS II. Our study supports these findings, because the PSI-LHC II membrane preparation is obtained in very high yield from stacked thylakoids. It appears likely that a significant amount of the PS I present is normally associated with LHC II and that multiple LHC II trimers can associate with the photosystem.

Author Contributions

A. J. B. performed the experiments. T. M. B. designed the experiments and T. M. B. and L. K. F. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02–98ER20310 (to T. M. B. and L. K. F.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- PS

- photosystem

- LHC

- light-harvesting chlorophyll protein

- SMA

- styrene-maleic acid

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- DM

- β-d-dodecyl maltoside

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- Chl

- chlorophyll.

References

- 1. Amunts A., Toporik H., Borovikova A., Nelson N. (2010) Structure determination and improved model of plant Photosystem I. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3478–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chitnis P. R. (2001) PHOTOSYSTEM I: function and physiology. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 593–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu H., Zhang H., Niedzwiedzki D. M., Prado M., He G., Gross M. L., Blankenship R. E. (2013) Phycobilisomes supply excitations to both photosystems in a megacomplex in cyanobacteria. Science 342, 1104–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burnap R. L., Troyan T., Sherman L. A. (1993) The highly abundant chlorophyll-protein complex of iron-deficient Synechococcus sp. PCC7942 (CP43′) is encoded by the isiA gene. Plant Physiol. 103, 893–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boekema E. J., Hifney A., Yakushevska A. E., Piotrowski M., Keegstra W., Berry S., Michel K.-P., Pistorius E. K., Kruip J. (2001) A giant chlorophyll–protein complex induced by iron deficiency in cyanobacteria. Nature 412, 745–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bibby T. S., Nield J., Partensky F., Barber J. (2001) Oxyphotobacteria antenna ring around photosystem I. Nature 413, 590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Croce R., van Amerongen H. (2013) Light-harvesting in Photosystem I. Photosyn. Res. 116, 153–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qin X., Wang W., Wang K., Xin Y., Kuang T. (2011) Isolation and characteristics of the PSI-LHCI-LHCII supercomplex under high light. Photochem. Photobiol. 87, 143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galka P., Santabarbara S., Khuong T. T., Degand H., Morsomme P., Jennings R. C., Boekema E. J., Caffarri S. (2012) Functional analyses of the plant photosystem I–light-harvesting complex II supercomplex reveal that light-harvesting complex II loosely bound to Photosystem II Is a very efficient antenna for Photosystem I in state II. Plant Cell 24, 2963–2978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wientjes E., van Amerongen H., Croce R. (2013) LHCII is an antenna of both photosystems after long-term acclimation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drop B., Yadav K. N. S., Boekema E. J., Croce R. (2014) Consequences of state transitions on the structural and functional organization of Photosystem I in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 78, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takahashi H., Okamuro A., Minagawa J., Takahashi Y. (2014) Biochemical characterization of Photosystem I-associated light-harvesting complexes I and II isolated from state 2 cells of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 1437–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raschle T., Hiller S., Etzkorn M., Wagner G. (2010) Non-micellar systems for solution NMR spectroscopy of membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 20, 471–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Serebryany E., Zhu G. A., Yan E. C. (2012) Artificial membrane-like environments for in vitro studies of purified G-protein coupled receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scheidelaar S., Koorengevel M. C., Pardo J. D., Meeldijk J. D., Breukink E., Killian J. A. (2015) Molecular model for the solubilization of membranes into nanodisks by styrene maleic acid copolymers. Biophys. J. 108, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Orwick M. C., Judge P. J., Procek J., Lindholm L., Graziadei A., Engel A., Gröbner G., Watts A. (2012) Detergent-free formation and physicochemical characterization of nanosized lipid-polymer complexes: Lipodisq. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 4653–4657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Long A. R., O'Brien C. C., Malhotra K., Schwall C. T., Albert A. D., Watts A., Alder N. N. (2013) A detergent-free strategy for the reconstitution of active enzyme complexes from native biological membranes into nanoscale discs. BMC Biotechnol. 13, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Swainsbury D. J., Scheidelaar S., van Grondelle R., Killian J. A., Jones M. R. (2014) Bacterial reaction centers purified with styrene maleic acid copolymer retain native membrane functional properties and display enhanced stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 11803–11807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Orwick-Rydmark M., Lovett J. E., Graziadei A., Lindholm L., Hicks M. R., Watts A. (2012) Detergent-free incorporation of a seven-transmembrane receptor protein into nanosized bilayer lipodisq particles for functional and biophysical studies. Nano Lett. 12, 4687–4692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Delepelaire P., Chua N. (1979) Lithium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of thylakoid membranes at 4 °C: characterizations of two additional chlorophyll a-protein complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 111–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Metz J. G., Bricker T. M., Seibert M. (1985) The azido[14C]atrazine photoaffinity technique labels a 34-kDa protein in Scenedesmus which functions on the oxidizing side of Photosystem II. FEBS Lett. 185, 191–196 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Feissner R., Xiang Y., Kranz R. G. (2003) Chemiluminescent-based methods to detect subpicomole levels of c-type cytochromes. Anal. Biochem. 315, 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pernodet N., Maaloum M., Tinland B. (1997) Pore size of agarose gels by atomic force microscopy. Electrophoresis 18, 55–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Narayanan J., Xiong J. Y., Liu X.-Y. (2006) Determination of agarose gel pore size: absorbance measurements vis-á-vis other techniques. J. Phys. Confer. Series 28, 83–86 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berthold D. A., Babcock G. T., Yocum C. F. (1981) A highly resolved, oxygen-evolving Photosystem II preparation from spinach thylakoid membranes. EPR and electron transport properties. FEBS Lett. 134, 231–234 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bruce B. D., Malkin R. (1988) Subunit stoichiometry of the chloroplast Photosystem I complex. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 7302–7308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tjus S. E., Roobol-Boza M., Pålsson L. O., Andersson B. (1995) Rapid isolation of Photosystem I chlorophyll-binding proteins by anion exchange perfusion chromatography. Photosyn. Res. 45, 41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scheller H. V., Jensen P. E., Haldrup A., Lunde C., Knoetzel J. (2001) Role of subunits in eukaryotic Photosystem I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1507, 41–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Oort B., Alberts M., de Bianchi S., Dall'Osto L., Bassi R., Trinkunas G., Croce R., van Amerongen H. (2010) Effect of antenna-depletion in Photosystem II on excitation energy transfer in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biophys. J. 98, 922–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kirchhoff H., Sharpe R. M., Herbstova M., Yarbrough R., Edwards G. E. (2013) Differential mobility of pigment-protein complexes in granal and agranal thylakoid membranes of C3 and C4 plants. Plant Physiol. 161, 497–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ihalainen J. A., Jensen P. E., Haldrup A., van Stokkum I. H., van Grondelle R., Scheller H. V., Dekker J. P. (2002) Pigment organization and energy transfer dynamics in isolated Photosystem I (PSI) complexes from Arabidopsis thaliana depleted of the PSI-G, PSI-K, PSI-L, or PSI-N subunit. Biophys. J. 83, 2190–2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caffarri S., Croce R., Cattivelli L., Bassi R. (2004) A look within LHCII: differential analysis of the Lhcb1–3 complexes building the major trimeric antenna complex of higher-plant photosynthesis. Biochemistry 43, 9467–9476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ruban A. V., Calkoen F., Kwa S. L. S., van Grondelle R., Horton P., Dekker J. P. (1997) Characterisation of LHC II in the aggregate state by linear and circular dichroism spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1321, 61–70 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kouřil R., Zygadlo A., Arteni A. A., de Wit C. D., Dekker J. P., Jensen P. E., Scheller H. V., Boekema E. J. (2005) Structural characterization of a complex of Photosystem I and light-harvesting complex II of Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochemistry 44, 10935–10940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Danielsson R., Albertsson P. A. (2009) Fragmentation and separation analysis of the photosynthetic membrane from spinach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Danielsson R., Albertsson P. A., Mamedov F., Styring S. (2004) Quantification of Photosystem I and II in different parts of the thylakoid membrane from spinach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1608, 53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Albertsson P.-Å., Andreasson E., Stefansson H., Wollenberger L. (1994) Fractionation of the thylakoid membrane. Methods Enzymol. 228, 469–482 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang S., Scheller H. V. (2004) Light-harvesting complex II binds to several small subunits of photosystem I. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3180–3187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Callahan F. E., Wergin W. P., Nelson N., Edelman M., Mattoo A. K. (1989) Distribution of thylakoid proteins between stromal and granal lamellae in Spirodela. Plant Physiol. 91, 629–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vallon O., Bulte L., Dainese P., Olive J., Bassi R., Wollman F.-A. (1991) Lateral redistribution of cytochrome b6/f complexes along thylakoid membranes upon state transitions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 8262–8266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]